![]() ORGANIZATIONAL BUYING BEHAVIOUR

ORGANIZATIONAL BUYING BEHAVIOUR

Application: Sales, Marketing Communications, Strategy

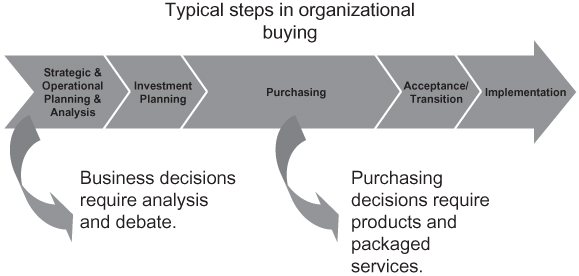

Figure O.1: A representation of the broad (very broad) stages in organizational buying

The Concept

One of the main differences between organizational buying and consumer buying is the more formal recognition of the role of different individuals in the business DMU. This affects the sales cycle because the sales team needs to talk to and nurture more people (see separate entry under sales); and governance rules in Western companies seem to be increasing this method of buying. For their article in the Harvard Business Review two researchers (Trailer, B. and Dickie, J., 2006) surveyed over 1,200 companies. They found that the individual “economic decision maker” was being replaced by: “committees and multiple layers of approval, all equally important to the decision to move ahead. This is partly why the length of the average sales cycle keeps increasing.” They found that companies reporting a sales cycle of seven months or more had climbed from 18% in their previous surveys to over 25% and those under three months had dropped from 50% to under 42%. Suppliers have to become knowledgeable about the roles of these different people, the weight given to different purchase criteria, and the sources of information used to come to a decision.

Marketers can be particularly troubled by purchasing managers (a significant participant in the organizational buying process) when they first encounter them. These specialists, often professionally trained, are employed to get the best value for their organization. Contrary to popular belief, though, they do not just want the cheapest price. In fact, some deliberately cut out the lowest (and the highest) priced suppliers in any buying process because of concerns over quality of delivery. They will have a clear set of criteria by which they will evaluate and decide. Inordinate effort must be made by sales people to understand those criteria and how their offer is perceived to measure up against them.

There are clear differences in the way different organizational buying groups behave in different sizes of company. For instance, the influence of the chief executive is likely to be more dominant in smaller companies and, because they have limited expertise, they are likely to filter information through trusted advisors or business networks. However, even in the very largest firms, the buying of some offers, such as consultancy, can sometimes be impulsive and individual with little involvement from purchasing specialists, although this is decreasing as corporate governance and risk management become more important to shareholders and policy makers. The situation is complicated by changing business strategies, by the network of relationships between firms, by the interactive nature of dialogue, by governance requirements, and by the influence of the formal purchasing function (particularly in government or other public sector purchases).

History, Context, Criticism, and Development

Although people have been marketing and selling to organizations for several centuries, it is only relatively recently that thoughtful, careful research and conceptual work has begun to emerge around how organizations buy. Some of this is really helpful to practising marketers wanting to think through new strategies and approaches.

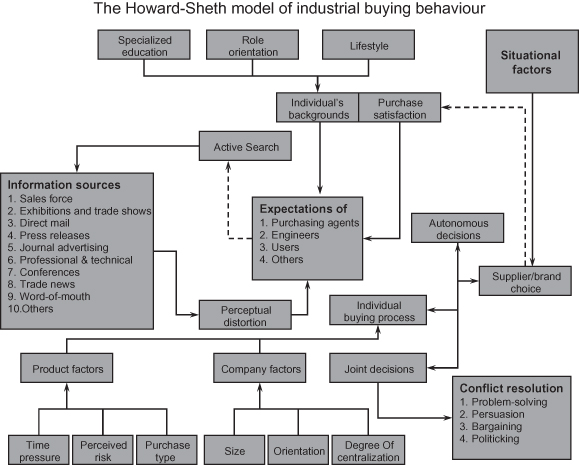

One of the earliest and best known models, for instance, is the Howard-Seth model of organizational buying, shown in Figure O.2. Published in 1973 it looks, for instance, at the role of expectations on buying and tries to separate “autonomous decisions” from “joint decisions”. Both of these are useful to know in the practical sales and marketing activities aimed at any organization.

Figure O.2: the Howard-Seth model of organizational buying processes

Later developments in this field have created different models and explored different, useful issues. One piece of work, for instance, (published by N.C.G. Campbell in 1985) distinguishes between: “competitive buying”, “cooperative buying”, and “command buying”. It challenges the assumption (made by many sales people) that all systematic organizational buying is combative and involves formal proposals aimed at getting the lowest prices.

This field also examines the diffusion of ideas and new products into organizations and how that affects the buying process. This is, though, a young and developing field of work with relatively little reliable and proven work. There also seems to be little to distinguish between the organizational buying of, say, large corporations, national government, local public sector, charities, private firms, and partnerships. Nor does there seem to be extensive work on the effect of variations in international culture on organizational buying.

Voices and Further Reading

- Wilson, A., The Marketing of Industrial Products. Hutchinson, 1965.

- “Organizational buyers are those buyers of goods and services for the specific purpose of industrial or agricultural production or for use in the operation or conduct of a plant, business institution, profession or service. Such buyers act on behalf of organizations for the furtherance of organizational, rather than personal goals.” Marrian, J. in Wilson, 1965.

- “Organizational buyers are those buyers of goods and services for the specific purpose of industrial or agricultural production or for use in the operation or conduct of a plant, business, institution, profession or service.” Marrian, J. in Wilson, 1965.

- Shapiro, B. and Posner, R.S., “Making the major sale”. Harvard Business Review, July–August 2006.

- Bonoma, T.V., “Major sales: who really does the buying?” Harvard Business Review, July–August 2006.

- “Business-to-business marketing, organizational buying behaviour ” Woodside, A.G. and Ferris-Costa, K.R. in Baker, M.J. and Hart, S. (eds), 2008.

Things You Might Like to Consider

(i) Some have suggested that organizational buying is more rational and objective than consumer sales because of the existence of objective evaluation processes and the buying function. Yet emotion still plays a part in business sales. People at work make emotional decisions as much as (some would argue more than) logical, objective, and analysis-based decisions. A chief executive may want to buy an IT outsourcing service from a particular firm because he fears acquisition and wants to use the brand of his supplier to reassure shareholders. A business buyer may be worried about the impact of a purchase on their budget, or their political standing after choosing a poor performing supplier. Above all, though, as executives develop in their career they rely more and more heavily on the beliefs, opinion, and intuition that they have developed through long experience in their industry. As they become more senior they deal with more strategic and less clear cut issues, so rely on their judgement (or “gut instinct”) even more. This means that, despite governance and rational processes, senior business leaders take intuitive and emotional decisions and must be influenced at that level. Experience suggests that suppliers who understand these emotional dynamics achieve higher value sales.

(ii) The different cultures of different sizes and styles of organization affect their approach to buying. A large centralized organization, will have different buying approaches to, say a decentralized organization like a large private partnership; these will be different again to a privately owned firm or a government or quasi-governmental body.

(iii) A large number of companies in different industrial sectors have avoided some of the cost pressures of formal organizational buying by “going up the value chain” (as they describe it). Companies offering computing, telecommunication, and accounting services to large businesses have developed consultative skills and used them to create a strategic dialogue with senior people. They have found that this has earned them advisory revenues of some size. It has enabled them to advise on any tenders that are issued, giving them the opportunity to influence the tenders more toward their own capabilities. They have also found that, after earning trust at senior levels, through relationship development (see separate entries under relationship marketing and AAR) they have been given some work without it going to tender at all.

![]() RATING: Practical and powerful

RATING: Practical and powerful