![]() CATEGORY MANAGEMENT

CATEGORY MANAGEMENT

Application: Sales Strategy, Marketing Strategy, NPD, Promotional Planning

The Concept

Category management, which is (at the time of writing) strongest in the retail sector, suggests that a product range is sold with different groups of similar, competitor products. These product categories (like frozen foods or toothpastes) are easily recognized and understood by customers. Each category is run within the organization as a business unit with its own targets and strategies. The introduction of the approach seems to change the relationship between retailers and suppliers; making it more collaborative. It prompts exchange of information, sharing of data, and joint business building. For instance, the emphasis moves to the turnover of the category as whole, not just the sale of individual products. Suppliers are expected to suggest new products or promotions that benefit the turnover of the total category and be beneficial to the shoppers interested in that category.

The idea developed for several reasons. First, retailers wanted suppliers to add value to their business rather than just fight for shelf space with other brands in the shop. Up until then, competition between manufacturers would change share within a product group but yield no incremental gain for the retailer. Secondly, suppliers saw it as a way of countering the rise in power of “own brand” items. It was also realized that there was more profit to be made in increasing the total level of sales in a product group than through harsh, relentless negotiation over price alone. In addition, collaboration meant that suppliers’ knowledge of their market could be accessed by retailers, smart marketers also realized that a considerable amount of work in developing a category could be delegated to their suppliers.

In 1992, the research company Nielsen defined category management as: “a process that involves managing product categories as business units and customizing them (on a store by store basis) to satisfy customer needs”. This is probably a little off because customizing product groups on a store-by-store basis is logistically difficult and does not seem to be considered a necessary part of category management; it is a concept now referred to as “micromarketing”. (The ability to analyse sales data by barcode and by individual store means that the traditional concept of “one range fits all” can be changed to this more flexible approach.) Nevertheless, many retailers manage stores by, say, size, and select product assortments accordingly. The definition does not adequately explain some practicalities for example, where demographic or marketing considerations take precedence, (such as stores tailored to the demographics of a local population).

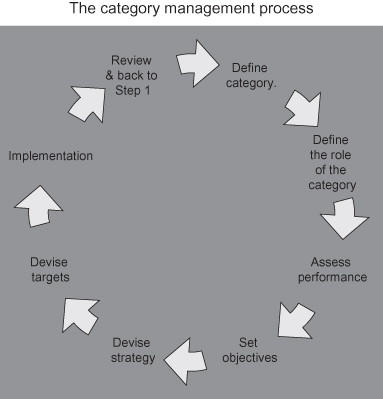

Nielson also developed a process by which category management could be handled. This “five-step process” included: reviewing the category, targeting consumers, planning merchandising, implementing the strategy, and evaluating the results. It has, though, generally been superseded by an eight-step cycle developed by the Partnering Group and represented in Figure C.1 above. Whilst being very comprehensive and thorough this has been criticized for being rather too unwieldy and time-consuming. Few suppliers say that they use the full process. They seem to use it as a basis to develop their own more streamlined approach, tailored to their own particular products.

Figure C.1: A representation of the generally accepted category management process

It appears to be commonplace for one supplier in a category (normally the one with the highest turnover in the product group) to be nominated by a retailer as a “category captain”. They will be expected to have the closest and most regular contact with the retailer and to invest time, effort and, often, money in to the development of the category. In return, they will gain a more influential voice with the retailer. For instance, in order to do the job effectively, they may be granted access to a greater wealth of data-sharing (e.g. more access to an internal sales database).

Interestingly, a similar approach seems to be evolving in service industries. Academics have suggested a number of different ways of categorizing services which will give useful insight into the dynamics of the business. There is evidence that the explicit management of business units within these categories and increased cooperation with customers (through a concept called the “co-creation of service”) has had beneficial effects similar to category management in product industries. Whilst there is not much evidence of “category captains” in this field, there is no doubt that many large technology providers have, for several years, grown used to an environment where a partner in one deal is a competitor in another. They have had to cooperate for the sake of their customers in different industry sectors. The service groupings are:

- Customized services versus “industrialized” (i.e. more process-based and packaged) services. The margins, approach to market, degree of engagement with buyers, and personnel used vary enormously between these two types of offers.

- Infrastructure-based services versus added value services. Some services are based on an infrastructure, a technology, or a network. They include water supply, computer “platforms” in major companies, telecommunications networks, networks of airline slots, or sets of maintenance contacts. The issues, development, and degree of reliance on that infrastructure affect the nature and the content of those services. Very often there is a core service (“communications” in telecommunication companies, “support” in computer maintenance companies, and “power supply” in utilities) and opportunities for added value services.

- Product-based services versus free services. Some services are adjuncts to product propositions and are therefore intimately tied to the value, development, and pricing of that product. Other services are unique propositions in their own right which will stand alone in the market place.

- Discrete (project) services versus continuously rendered (annuity) services. Some services (such as consultancy) are one-off discrete projects whereas others (like financial audit) are recurring contractual relationships. This difference affects pricing, customer relationship techniques, margins, and business structures.

- Technology-based services versus people-based services (high tech versus high touch). Some services (extranets for business buyers, for example) comprise technology through which customers are served. Other services are predominantly reliant on the skills of people.

- Self-service versus performed service. Some services are performed on behalf of a buyer, whereas others provide the means by which they can perform the service themselves.

- A membership relationship versus anonymity. This classification suggests differences according to the relationship of the buyer to the supplier. Membership may range from formal paid-for inclusion in a club to an emotional attachment to the group or community at whom the service is targeted. However, in many circumstances, buyers prefer anonymity or simple functionality and resist suppliers’ attempts to form an intrusive relationship.

- Transactional versus interaction services. Some services are short-term “transactions”. They are often low value and commoditized purchases. “Inter-actions”, though (a relatively new definition), are higher value, mutually profitable exchanges between a customer and a supplier over a long term.

History, Context, Criticism, and Development

The relatively recent concept seems to have originated in grocery retailing, and has since expanded to other sectors such as DIY, cash and carry, pharmacy and book retailing. It seems to have started in North America in the 1980s and prompted a change in relationships between suppliers and retailers (from adversarial to more collaborative). Nielsen appears to have begun publishing information around 1992, prompting the category management process to gain momentum across the Europe and Canada. At first, it was limited to supermarkets but, as the advantages became clearer, it spread into other sectors.

Two key things were needed in order to enable category management to evolve:

(i) The growing dominance of large retailers like Tesco in the UK and Wal-Mart in the USA. Before then, retailers were focused more on growth through harsh price negotiation and the building of stores. Likewise, suppliers would not have seen a return on investment in relationships with lots of small retailers; but with the emergence of fewer larger clients, the concept became attractive.

(ii) The explosion in information technology which meant that sales data (collected from barcodes) could be more efficiently collected and analysed for trends and information.

It is reported that, during the mid 1990s, category management seemed to be confused with rationalizing and clearing out duplicated products, seen as a one-off “spring-clean”. Following this initial hiccup, there was a brief period during which some retailers reverted to old-fashioned trading but category management then regained momentum, embracing many aspects which should have had more prominence the first time around (price architecture, promotional strategy, and shopper understanding). At the time of writing, category management is increasingly becoming a way of doing business. There is even a Category Management Association, formed in 2004, with members that come from a broad range of functions. It connects members with category management peers around the world, is a central resource for information and best practice, and is the only group certifying companies and individual category management professionals according to recognized industry standards.

Voices and Further Reading

- “Viewed purely as a strategy to reduce waste and therefore costs, CM loses its focus on the end customer as the absolute priority. Concreting on the maximization of shelf-space profitability may not improve customer satisfaction levels and that, in the long run, may reduce profits.” McDonald, M.H.B. and Wilson, H., 2011.

- Lovelock, C.H., “Classifying Services to gain strategic marketing insights”. Journal of Marketing, Summer 1983.

Things You Might Like to Consider

(i) As the amount of data increases category management is becoming highly “technology” and mathematics-orientated.

(ii) There is a large behavioural marketing element to the concept (for example in understanding the psychology of shoppers) and there is potential for real development in this technique.

(iii) Some politicians have viewed the increased collaboration between suppliers and retailers with suspicion and, perhaps, as a potential source of anti-competitive behaviour. The UK Competition Commission has, for instance, raised issues on market distortion in principle. They have also acted on milk price-fixing.

![]() RATING: Practical

RATING: Practical