![]() MARKET MATURITY

MARKET MATURITY

Application: Strategic Insight into Market Development, NPD/NSP, Communications Strategy

The Concept

The phenomenon of market maturity reflects changing patterns in demand and supply, and occurs when there are multiple suppliers and multiple buyers in a market. It is normally represented by an S-curve (as in Figure M.1 above) and, as a result, is frequently confused with the “product life cycle” of individual offers. This is also closely related to (and often muddled up with) a sociological phenomenon called “the diffusion of innovation”. (The latter is directly relevant to marketers because the products and services their companies offer are themselves part of innovative groups of offers which are diffusing across different societies in the world at different speeds.) Market maturity, though, is something distinct and different, the implications of which marketers need to understand.

Figure M.1 A representation of market maturity trends

This concept draws an analogy between biological life cycles and the sales growth of successful product groups, by suggesting that they are born, introduced to a market of human beings, grow in sales, mature (sales growth stops but profit growth continues), and then decline (sales fall). This organic analogy is probably relevant because the trend represents an iterative learning process between the buyers and suppliers in a market which mimics natural, organic growth. For example, a new mobile phone is easily communicated to a mature, sophisticated market which has grown used to the idea of mobile communication as part of life. Yet the extra cost of an iPhone would have been difficult to sell to a developing market where mobile communications did not exist. They would first have to accept the idea of mobile communication just as, at the time of writing, societies are beginning to think about, say, 3D television. So, taking a moment to understand the evolution of the macro market in which marketers operate is vital to the development of marketing strategy and campaigns.

At “birth” (the first introduction of the proposition to the world) a new concept sells poorly. Buyers are unaware of its existence, suspicious of the new idea, or experience problems when ordering (with production capacity, effective distribution, or product quality). Rogers, (who was largely responsible for the concept of diffusion of innovation, see Rogers, E.M., 2003) suggested that “bold” or “innovative” people buy the new product during this stage as a substitute for an existing product or to meet a newly identified need. They need to be shown how to use the innovation and how it is relevant to their lives. Suppliers need to educate the market in the concept and grow their business by inducing customers to try it. In this phase of a market’s life, costs are likely to be high and firms can be unprofitable because of the high cost of sale. As a result, it may be wise for any businesses wanting to enter completely new markets to wait for upstarts to burn investment and establish the concept. They can then enter by buying them out. Companies who have successfully marketed true innovations, like Apple with its iPhone, have used a range of concepts to induce trial and spread word-of-mouth like a contagion. They rely heavily, for instance, on PR to create demand and mavens (see viral marketing), like Apple’s “super users” to excite communities. Some argue (see Moore, G.A., 1991; Godin, S., 2004) that, with the disruption to broadcast media like TV and the interactive nature of digital marketing, marketers should concentrate on launching to these pioneers and encourage ideas to spread through viral marketing; to the exclusion of broadcast marketing aimed at later adopters.

As time goes by, customers become familiar with the concept and more buy it. In these early stages they frequently adapt it for different or unforeseen uses. When, for instance, the mobile phone markets began to expand in Western societies, suppliers tried to open new market niches, such as teenagers, with different styles of products. At the time, it was strange for youngsters to be given what was, until then, a luxury item often used only for business. These younger customers, with dextrous fingers from frequent use in computer games, did something unexpected. They started to use a little known facility to communicate (texting) which, at the time, was free in many markets. This opened up a new way to communicate, new patterns of behaviour, and even a new written language. The suppliers observed this behaviour and adjusted their products accordingly. They made keyboards friendlier toward texting, created new tools to help (predictive text), and changed tariffs to make it profitable.

In this phase, sales growth develops as a consequence of “word-of-mouth” communication (see viral marketing). Early buyers pass on the good experience of the product to others or re-purchase it. Producers and distributors (whether new to the market or well established) recognize the opportunity and switch over to produce their own version. The market broadens through policies of product differentiation and market segmentation. Profit margins grow as experience reduces unit costs and promotional expenditure is spread over a larger sales volume.

Quite frequently one product becomes the dominant offer and encourages more cautious buyers, “the late majority”, to enter the market. This product becomes a market standard elbowing all others into narrow niches or oblivion. The “IBM PC” became, for example, the standard for the personal computer market pushing the Apple Mac into a specific, quirky niche. Similarly “VHS”, “Hoover”, “Google”, and “Fedex” became the shorthand in their own markets for a whole product category.

The adjustments to innovations which come from the interaction between suppliers and early buyers, in turn, cause other people to buy and adapt them to their lifestyle. This increases the volume and the offer enters the growth phase of its market. There is strong natural demand and, in many cases, sales just walk through the door. In this phase of the market’s life the firm has to concentrate on servicing demand, so established suppliers will be focused upon obtaining and deploying skilled resource. They must also ensure that there are efficient processes to capture and meet orders. It is possible to concentrate on internal issues, ignoring competitor moves because there is sufficient demand for all. As a result these markets are relatively easy to enter in a low risk way. In fact, natural growth with a small venture is probably the best method of entry, particularly if a supplier has a well known brand or a large number of existing customers who are likely to want their offer.

Maturity occurs because all markets are ultimately finite (in time, volume, and geography), and the market becomes “saturated” (most people have bought their first one). Sales growth becomes more or less flat as sales settle down to a level which reflects the regular volume of new buyers entering the market plus re-purchase rates. Profits can initially decline because companies need to adjust to the number of competitive offers. There can be some market consolidation during this transition which reduces competition. Companies can make cost reductions but those who succeed eventually thrive and become profitable though segmentation and real differentiation, normally achieved by hard trial and error.

Most buyers are familiar with the concept and have made their initial purchases. Sales growth in the market comes from replacement or added value sales, from innovation with new market segments. However, although established businesses in this type of market may be struggling to gain substantial sales, this is often a good time for new entrants to gain a foothold by attracting the attention of a few specific buyers and offering an experience that is truly different. They can, for instance, command the attention of a distinct niche of customers, carving out a profitable and enduring position for their firm by redefining the accepted rules or behaviours in the market (see market definition).

Most suggest that “decline” then occurs as buyers switch to new offers which offer advantages or benefits not present in the existing range. Producers initiate a new curve, bringing to an end that of the product group to be displaced. Declining sales are accompanied by falling profit margins as too many competitors fight for the remaining market. Price-cutting is prevalent and marginal competitors move out of the market. However, markets can be redefined or reinvigorated by legislation or new regulation.

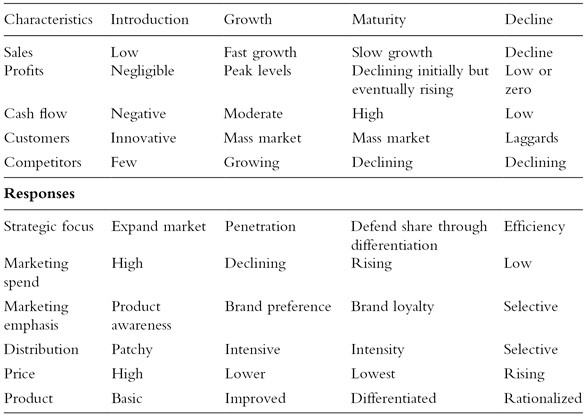

Normally, suppliers in a market are buffeted by the forces at play in each phase of its development. However, if marketers understand what stage of development their market is in, they can set strategic direction for their firm in the light of that insight and perform more effectively. An individual product being offered into a market place can then be adjusted in the light and understanding of the relationship to the market conditions. The likely strategies in each phase of market maturity were suggested by Peter Doyle and are summarized in Table M.1 below. Marketers should be cautious, though, of being too prescriptive about the adoption of these strategic stances as the case study below shows. The assumption that markets decline is challenged by both the experience of the British railway industry and some of the detailed analytical studies (see Polli, R. and Cook, C., 1969).

Table M.1 Strategic implications of different phases of industry maturity

Source: Doyle P., 1976

History, Context, Criticism, and Development

The market maturity concept has been tested, examined, criticized, and developed over the past four decades. It was observed by an economist and then brought to prominence by leading marketing writers. In 1962, for instance, Raymond Vernon published a paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics (Vernon, R., 1962) which was “a by-product of the hypothesis stage” of a study into the foreign direct investment of the United States (sponsored by the Ford Foundation at Harvard). Just as significant, though, was the fact that his work was also published as part of a conference held by the American Marketing Association (“Emerging concepts in marketing”, December 1962). There is little doubt that this kick-started the interest in product life cycles, diffusion of innovations, and market maturity amongst marketing specialists.

He pointed out that, at the time, the relative conditions of the US economy (higher labour costs and high disposable income) had led to the development of products (“the drip-dry shirt”) which would not take off in other countries where, say, labour (“laundresses”) was cheaper. He reviewed many reasons for starting labour-saving product innovations in the USA and settled on communication as a prime one. He described the “maturing product” and used the standardization of one product group (radios) as an example. His paper also quoted research into the office equipment and electronics industries. It used S-curves to show the phase of development of markets (he described them as: “new product”, “maturing product”, and “standardized product”) and how to understand when to invest abroad. His work was unquestionably about product groups and the development of markets. (Incidentally, there was no assertion in his work that the normal sales pattern of individual products or services was an S-curve.)

There have since been some detailed studies which seemed to substantiate this phenomenon. Two academics at MIT, for example, (Polli, R. and Cook, C., October 1969) reported on tests into the “observed sales in 140 categories of nondurable consumer products”. They tried to isolate certain variables like population growth and price changes. They also distinguished between: “product classes” (all those objects which are substitutes for the same need, e.g. cigarettes), “product forms” (“finer partitions of a product class”), and brands. Their work was numeric, objective, and thorough. It, by and large, confirmed the tendency toward an S-curve in product classes and product forms. The market maturity phenomenon for product groups appears to be a verifiable trend.

Voices and Further Reading

- Vernon, R., “International investment and international trade in the product cycle”. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1962.

- “All of these considerations tend to argue for a location in which communication between the market and the executives directly concerned with the new product is swift and easy…” Vernon, ibid.

- Wells, L.T., “A product life cycle for international trade?” Journal of Marketing, July 1968.

- “Empirical studies of trade in synthetic materials, electronic products, office machinery, consumer durables, and motion pictures have demonstrated that these products follow a cycle of international trade similar to the one which the model describes.” Wells, ibid.

- “The product life cycle concept … has been formulated as an explicit, verifiable model of sales behavior and tested against actual data in 140 categories of durable goods.” Polli, R. and Cook, C., October 1969.

- Swan, J.E. and Rink, D.R., “Fitting market strategy to varying product life cycles”. Business Horizons, January–February 1982.

- “… entire industries have developed ways and means of operating efficiently within a particular PLC. The apparel industry, for example, has developed systems of rapid manufacture and distribution of clothing in order to live with the relatively short fashion cycle.” Swan and Rink, ibid.

- “The telephone, the Beatles, the PC, the automobile, and many, many more other great innovations were derided early on. The absolute maximum size of the US car market was once established to be 20,000 since that was the number of those who could afford chauffeurs.” Ambler, T., 2003.

Things You Might Like to Consider

(i) The market maturity curve is often mistakenly referred to as the “product life cycle concept”. Yet the phenomenon occurs in the sales volume of product groups over time, not individual products. There must be multiple suppliers and multiple buyers in markets that develop over time for it to be observed. (Individual products rarely go through a sales history similar to an S-curve. Most die soon after launch.)

(ii) As the phenomenon occurs when there are independent variables (i.e. groups of suppliers and buyers) it can be used to create marketing strategy. Many have found that the concept can be used to form a judgement about movements in the category’s sales growth curve. They can develop marketing strategies appropriate to each stage in the life cycle.

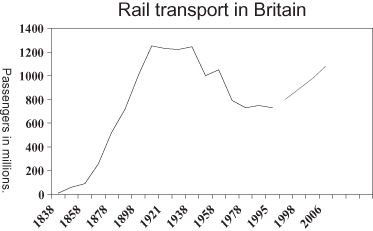

(iii) Changes in the shape of markets, or categories within markets (e.g. filter cigarettes within the overall smoking market or rail journeys in the overall transportation market) may not be straightforward. They may be distorted by other macro economic forces as the case study below shows.

(iv) It is rather a shame that discussion of this subject tends to begin with the “introduction” phase and the “innovators”. Marketers should also understand and consider “latent markets”; those that do not exist. For instance, in 1977, Ken Olsen, (the founder of DEC) said that there was “no reason why anyone would want a computer in their home” and, in 1947, the chairman of IBM said that he thought there would only ever be a world market for “about five computers”. The Economist magazine reported that, in the 1980s, AT&T had asked McKinsey to estimate how many cellular phones would be in use in the world by the year 2000. A consultant (who still works for them at the time of writing and is, apparently, teased mercilessly by colleagues) noted all the problems with the then innovative devices (heavy handsets, poor batteries, awful network coverage, and costs). The advisers estimated the total worldwide mobile phone handset market would be about 900,000 by the year 2000(!), prompting AT&T to pull out of the market. People do not know what they want or desire, logic does not apply to the creation (or timing) of markets. Marketers need to develop clear, professional judgement about their advent and evolution.

Transportation markets in the 20th century

One of the industries that grew enormously during the 19th and 20th centuries was transportation. It enabled the mass movement of millions of people, the creation of new towns, new lifestyles, and new methods of working. Also, as technology evolved (and as Professor Levitt pointed out in his 1960 article) new forms of transportation opened up new markets.

It is possible to see the market maturity curve from long-term perspectives of these evolving markets. The diagram below, for instance, is based largely on figures from a historian (Hobsbawm, E., 1999) and shows passenger rail journeys in Britain since their inception. (The figures since 1999 come from the industry’s publicly released results.) The market maturity curve can clearly be seen. Interestingly, though, since the 1990s, changes in socio-demographics, government policy, and the values of society have meant that rail travel in Europe has experienced a renaissance. This alone shows the dangers of using these trends to develop strategy. Rail was in decline in the 1960s as car travel grew and, as a result, rail infrastructure was cut back. At the time of writing, though, there are more rail journeys in Britain than ever before. The graph has kicked back up again. Marketers (contrary to what strategists would have recommended in this “mature/declining” industry) are launching campaigns to compete against both air travel and car journeys. They are growing a supposed falling market.

Figure M.2 A graphical representation of passenger rail journeys in Britain since the technology’s inception

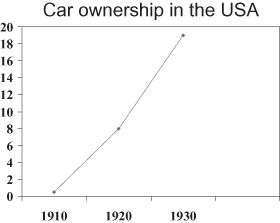

Figure M.3 A graphical representation of the advent of car ownership in the USA

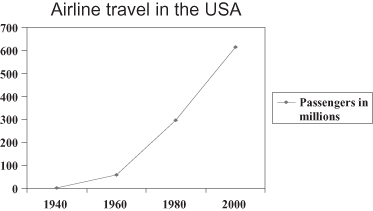

Figure M.4 A graphical representation of the growth in American air travel

The source of the other two graphs is an American business historian (Koehn, N.F., 2001). They chart the rise of American car ownership in the first half of the century and air travel as it changed from a rarity (in the early sixties when Sinatra could convey romance with “Come fly with me”) to when it became commonplace (and anything but romantic in the public imagination). The industry maturity curve can clearly be seen. Yet again, though, marketers ought to be cautious about assuming that these booming markets will continue. The problems with oil, the slowly changing values to a greener society, and the Obama administration’s policies toward high speed rail, may yet make other transportation options viable careers for marketers of the future.

![]() RATING: Practical and powerful

RATING: Practical and powerful