![]() COMPETITIVE STRATEGY

COMPETITIVE STRATEGY

Application: Strategy and Planning, Revenue Success

The Concept

The ability, style, and will to compete are issues that marketers need to consider as they design their work. There are times when the actions of individual competitors are of immediate concern, such as during a proposal to a customer. More important, however, are the times when changes in the business or the market allow actions by other firms to threaten the health of the business. Competitive response then becomes a major strategic issue which needs to be addressed.

Companies in a range of markets can be complacent and engrossed in internal work. They can develop a tendency to focus more on the improvement and presentation of their own offers rather than any specific attack on vulnerable competitors. Experience suggests that, as mature markets tighten, marketers need to think more explicitly about their competitive strategy. They have to concentrate on how to attract business to them rather than letting it go to other firms. Even more importantly, they need to find processes whereby that competitive strategy, once developed, can be implemented throughout their organization.

For example, it may be that a firm which has been number two in its market decides that the time has come to challenge for leadership. This means taking the position of the established market leader in a deliberate and planned way, backed by proper investment. The rewards of such a move are great. It implies that this “challenger” will seek to gain the leading buyers in the market and aim to have the dominant share of the budgets of those consumers. It must also offer the value proposition which appeals to most of the customers in the market and keep it in line with changing needs. The firm will become the leading authority on technical matters and policy issues within its own market place, advising regulators and industry advisers. In short, it must behave like the market leader. However, such a strategy will not be viable if the leadership espouses it but the firm itself carries on as it has always behaved.

Alternatively, a firm may settle on a “niche position” (see positioning) based on some source of differentiation. A truly differentiated offer will enable it to earn greater margins and attract more customers than the industry average. However, this will simply not be feasible if the experience the customers have is much the same as it always has been and is no different from other providers.

The challenge of competitive strategy, then, is not just to set direction or to deal with ad hoc competitive threats as they occur but to implement a competitive stance throughout the organization so that it becomes an effective guide to day-to-day management decisions. There are a number of approaches that seem to have proved effective over time.

(i) Porter’s Three Generic Strategies

Michael Porter (Porter, M., 1995) has made a major contribution to the thinking on competitive strategy over several decades. These ideas can be used by marketers to shape the firm’s strategic focus. Among other things he has argued that firms should focus on one of three generic competitive strategies. They are:

- Overall cost leadership. The organization concentrates on gaining the lowest costs of production and distribution, and thus has the ability to set lower prices. Whether it does that or not depends on its objectives in its market. Some set lower prices to gain volume share; others maintain higher prices to increase margins. Cost leaders achieve their aims by very tight cost control across all areas of the business. This is helped by having a large scale of operations and opportunities for economies of scale, perhaps internationally. The basis of cost control is the “experience curve” (see Boston Matrix), globalization of operations (by focusing production in cheaper parts of the world), labour efficiency, the rewards of global brand development, and innovation of design.

- Differentiation. In this, the supplier focuses on a component of the market offer which is important to buyers and emphasizes it in its business dealings. Normally it is: brand, quality, innovation, or technology.

- Focus. Here the firm concentrates on one or more market segments. By doing this, the marketers are able to gain in-depth knowledge of the segments and tailor the approach in detail. This best suits small firms, able to focus on a portion of the market.

(ii) Positioning As a Competitive Tool

Market positioning is based upon customers’ views of value, which is a derivative of quality and price. Each company involved in a market takes its own position in that market, whether by design or default (see separate entry). They may become: market leader; market challenger; premium supplier; niche; or least-cost. This is the competitive position of the firm and ought to be the orientation of everyone in it. Also, the prices and features of the offers ought to be different. For example, the offer of a least-cost supplier ought to be very different to that of a features-rich premium supplier. Each makes money in a different way from different groups of customers.

The power of positioning strategies is that they are built upon customers’ value perceptions. If constructed using research, they can clearly indicate what the firm needs to do to its offer in order to move to one of the long-term viable market positions. If, for example, customers perceive there to be no “premium” supplier or no “least-cost” service, then the marketer has discovered a vacant position into which to move the firm. This can also be used to anticipate the moves of competitors or to understand shifts in the whole market.

(iii) Military Analogies As a Guide to Developing Competitive Stance

Several academics have suggested that military language and approaches are useful analogies in the development of this competitive stance (see, for instance, Wilson, R.M.S., Gilligan, C., and Pearson, D.J., 1992).

They suggest:

- Market leaders are in the most powerful position and tend to adopt certain behaviours (see Treacy, M. and Wiersema, F., 1995). They need to maintain their lead by consolidating brand, customer relationships, and employee loyalties while honing their offer over time. Although they will be assailed by most competitors, they can, if necessary, affect all of them by changing the rules of the game. If the marketer changes the price and offer of a market leader, all others will have to move because they have changed the value equation of the whole market. The market leader can, for example, initiate a price war in order to damage competitors. Before doing so, it should estimate carefully how far it can afford to reduce margins and how low competitors can afford to go in response. An alternative is to invest in new uses for its skills or to seek to grow the whole market.

Market leaders are, though, constantly under threat from the various competitors. Their competitive strategy is therefore largely defensive. The firm can adopt a “position defence” (holding on to a supposedly impregnable fixed position), although this is thought to be the weakest defensive strategy, causing the firm to progressively retreat. A “mobile defence”, on the other hand, is to move into other areas which might prove to be leading offers in the future. Whereas “flanking defence” means attacking vulnerable areas such as an unaddressed part of the market. “Contraction defence” is a withdrawal from a certain area in order to use resources more effectively, “pre-emptive defence” is to make a move before that of a competitor, and “counter-offensive defence” is a response to an attack from a challenger.

- Challengers, being strong competitors with abundant resources, have a number of competitive strategies open to them. They can attack the market leader, attack peers, attack smaller firms, or seek to maintain the status quo. Their attacking strategies are: a “full frontal assault”, a direct challenge for leadership needing superior resources, a “flank attack”, using technology or market opportunity to focus on a vulnerable area, an “encirclement attack”, striking in several areas of business at once, and a “bypass attack”, competing against indirect or less important parts of the market.

Whether or not the strong competitor thinks in these terms, it will need to consider its market position and how it affects the health of its business. It may be that it can hold its position and maintain its earnings by seeking to preserve the status quo in a steady market. However, it may be forced to take business from others to maintain earnings or to satisfy the ambitions of the business owners. If it settles for a “full frontal” attack on the market leader, for instance, it needs to ensure that it has the resources for the battle. If not, it is sensible to consider the benefits of focusing its resources on another competitor’s offer.

- Niche suppliers are normally smaller and more focused firms who, again, have several options. They might adopt an “alliance strategy”, working with another firm to challenge the business of others or they might adopt a “guerrilla strategy”, gaining the loyalty of one market group. The latter is about using the strength of being small and fleet of foot against the larger competitor. Whether or not these smaller firms use this approach to plan their business development, they need to be obsessive about their point of specialization and use their smaller resources judiciously to secure their business growth.

(iii) Service Quality As Competitive Strategy

It is surprising how many companies, who consider the quality of their after care service to be an important part of their offer, do not think through the place of service in their competitive strategy. Service programmes are often imprecise and vague, thereby losing any potential competitive advantage. It is sensible to develop a clear, competitive strategy for the service of the company which matches the general business strategy; for service style to reflect market position. If the firm is a least-cost, premium, or niche supplier, its competitive position is reinforced if its after care is undertaken in a style similar to that positioning.

As important is to recognize the moments in the evolution of a market when there is a strategic opportunity to gain ground by offering a new style of service. Industries appear to develop through an evolution of thought and strategy with regard to service standards. Some have reaped enormous rewards when taking advantage of those moments. The first phase is to reach a national par. This is a common expectation of service quality which is shared by the population as a whole. It is assumed, ill-defined, and emotionally based, but is a common value nonetheless. For various reasons (such as a historic monopoly or legislative distortion) the service provided by an industry may be below this expectation. A service which is far below par will eventually become the subject of national ridicule: the target of comedians and journalists because they recognize that there is a common experience which can be exploited. In an industry where all suppliers are criticized, the first supplier to move to meet national par will gain market share. This has happened in numerous industries in both a national and international context.

These unique strategic opportunities for a few suppliers in passing moments of developing industries have become the examples used by many of the service quality and customer care gurus. Few have gone on to look at the opportunities to use service quality as a strategic asset in other phases of market development. For example, once competitors notice that a company is taking a lead through quality they begin to develop programmes of their own. As a result, the service of competitors begins to catch up. They then look for ways to communicate the efforts that they have made in order to attract them back. The industry goes through a phase where it “markets” the quality of service that it provides.

Once the industry is filled with suppliers communicating common quality of service propositions, it must evolve further. It moves towards “service differentiation”. This is a process which results from changes in attitude among both buyers and suppliers. If all suppliers are making similar quality claims, then buyers choose on the basis of service style and price. They are attracted to an ambience, design, or behaviour which suits their taste. Suppliers therefore respond by developing different service offerings for different groups. Clearly, if the industry is not yet at this stage, a marketer can gain competitive advantage by anticipating it. They can choose the most attractive segments and design a service which appeals primarily to them. For instance, in an industry where all services are designed for naïve customers, the service standard comprises: good client care, clear process, smiling people, and a reassuring brand. However, because of the need for emotional control (see services marketing), frequent purchasers can become frustrated with this approach. For them, good service is self-service and streamlined process. By constructing a service which has, at its heart, the sense of privilege, of joining a club, the supplier can provide better quality service at less cost. If a marketer introduces a new standard of service for experienced clients, it will attract them from other providers.

There is then a stage of service evolution when “added value” services are offered to the market. Buyers are able to recognize the value of the base service and are thus willing to pay extra for added value service features. Competitive advantage can be gained by launching packages of added value services for the segment that the firm is targeting. The difficulty is that the incremental value of the added value features is eroded over time as standards improve. Buyers then expect them to fall into the base service. Suppliers must continue to create new added value features to distinguish them from the core service in order to maintain their competitive lead in their chosen segments. So, the creation of the new service standard can be a competitive weapon.

(iv) Value Chain Analysis

This concept suggests that marketers view their businesses as a series of activities, linked in a process or “chain”, each of which adds value to raw materials (see Porter, M., 1995). The concept is familiar in manufacturing businesses and is used to find items of extraneous costs. However, it can also be used to identify areas of potentially greater added value and areas of competitive advantage. Theorists have also developed a generic value chain model for service businesses (see Heskett, J.L., Sasser, W.E., and Schlesinger, L. A., 1997).

Competitive tracking and analysis: As with other areas of strategy, decisions about competitive response are more likely to benefit the firm if based on market insight and good analysis. Information which is typically sought about competitors relates to their:

- objectives and plans

- performance

- structure and organization

- senior management changes and the decision-making track record of those assuming leadership roles

- strengths and weaknesses

- products, services, and pricing

- marketing materials and campaigns

- wins and losses

- response profiles, (i.e., are they opportunistic or thoughtful in their selection of business targets?)

Without such a system to inform leadership about competitor response, information can be anecdotal and, quite simply, wrong. More than one business has thought itself to be the market leader in a field of work but, once objective analysis was undertaken, discovered that it had been overtaken. It is sensible to establish a system to gather objective knowledge about competitor moves. To achieve this, specialist agencies, people, and processes exist which can be easily accessed by marketers.

Sources of competitive advantage: One of the most important aspects of competitive strategy is to find sources of competitive advantage. They are likely to include:

(i) The “core competence” of the business (see Hamel, G. and Prahalad, C.K., 1994)

This idea suggests that each company has a skill or function in which it invests over time because it is seen as the most important task of the organization. Often this is made a priority unconsciously because it is so obviously the most important task. It is the area of responsibility which always receives time, attention, and investment, almost without question, in comparison to other functions. Because of investment in both people and resources, this area is likely to improve in both performance and cost. It is represented as an “experience curve” (see Boston Matrix). Unfortunately, despite the fact that many strategy experts emphasize the importance of the core competence, there are few recognized techniques to define it. It can usually be determined in discussion, or brainstorming, with senior management. Such discussions can seem vague and difficult but, once the “blinding flash of the obvious” occurs, the simple heart of the company’s performance can be exploited as a competitive expression of skill.

(ii) Brand

A company’s brand or brands are a source of competitive advantage. They will appeal to the target market causing them to relate to it in such a way as to purchase over time. Customer loyalty is fostered by brands because they give reassurance in any emotional aspect of buying or using a product or service.

(iii) Customer relationships

The relationship between a company and its customers is also a source of competitive advantage, called by some accountants “customer equity” because it is seen as an intangible asset. The heritage of contact between the people, processes, and systems of the two organizations cannot be duplicated (see business-to-business marketing, relationship marketing, and AAR). A company’s relationships will include some who are very loyal and others who could be made more loyal. They are a source of competitive advantage because they are more inclined to purchase and repurchase. They are also likely to be advocates of the firm. This might be turned into highly profitable growth through a structured relationship programme.

(iv) Distribution

The way a firm reaches its clients is a source of competitive advantage. This might be the location of a shop to attract the best flow of buyers but a similar dynamic applies in business-to-business marketers. A firm might decide that it needs to open an office in a city or region where it identifies potential demand. It will need to secure a facility, assemble resources, and launch the new presence.

(v) Critical success factors

Any market has established rules of engagement by which the participants in the market survive or prosper. These rules may be imposed by regulatory or market pressures, and usually by a combination of the two. For example, in a professional services industry all of the participants must meet the necessary legal or industry standards of qualifications and behaviour in order to be able to participate. Meeting these criteria is a critical success factor as it is not possible to trade without them. Beyond these basic requirements for being “in the game”, suppliers also face certain criteria which enable them to succeed in the market place. However, the critical success factors for this are commercial imperatives resulting from the evolution of forces within the market. The way marketers create, implement, and manage these “motivators” can be a source of competitive advantage.

History, Context, Criticism, and Development

Competitive strategy and behaviour has been a fact of marketing and business life for many hundreds of years. It was in the latter half of the 20th century that many of the concepts related to competitive strategy began to emerge. The fight for market share, for instance, existed in many markets amongst many leading companies well before the PIMS survey and thinkers like Bruce Henderson demonstrated the advantages in terms of profits and success for those with a dominant share. The work by Michael Porter around different sustainable competitive positions similarly articulated viable strategies for business leaders. There are now a range of credible concepts by which marketers can include viable competitive strategies in their plans.

Voices and Further Reading

“Although the vast majority of marketing strategies acknowledge the importance of competitive analysis, it has long been recognized that less effort is typically put into detailed and formal analysis of competitors than, for example, of customers and their buying patterns. In many cases this is seemingly because marketing managers feel that they know enough about their competitors simply as the result of competing against them on a day-to-day basis. In other cases, there is almost a sense of resignation, with managers believing that it is rarely possible to understand competitors in detail” Wilson et al., 1992.

- Hamel, G. and Prahalad, C.K., Competing for the Future. Harvard Business School Press, 1994.

- Porter, M., On Competition, Harvard Business Review book, 1995.

- Porter, M., The five competitive forces that shape strategy. Harvard Business Review, Januany 2008.

“Competitive behaviour refers to the attitude adopted by firms in its decision making process, with regard to its competitors actions and reactions. The attitudes deserved in practice can be classified … independent behaviour … co-operative behaviour … follower behaviour … leader behaviour … aggressive or warfare behaviour” Lambin, J., 2000.

“Competing on capabilities: the new rules of corporate strategy” Stalk, Evans and Shulman, in Stern 2006.

Things You Might Like to Consider

(i) It is possible for the leadership of a firm to give it a competitive emphasis, or a “stance”, which permeates the organization.

(ii) Many of these concepts are based on assumptions about market share and growth which may not apply to some markets (see separate entry on market share). There does not yet seem to be the depth and quality of research into their applicability to the unique dynamics of, say, professional service industries as have been applied to other areas of marketing.

(iii) It is clear that strategy is valued by the military and is thought to pay off in success in battle. The direct applicability of these tactics to management and leadership teams while they are constructing day-to-day strategy or policy seems to be less evident. Many of the anecdotes and case studies used in the work to promulgate this militaristic view of competitive strategy appear to be more post event application to illustrate an interesting thesis rather than practical business thinking used proactively.

British Gas Competes for the First Time

In the late 1990s the senior managers of one of Britain’s leading utilities, British Gas, were worried and a little frightened. They had been privatized and their business gas market had been opened to competition. Unfortunately, their experience of that competitive force had not been good. After many decades of having 100% of the market, they had braced themselves for losses. It had been, though, a huge and dramatic loss which had forced the leaders of the organization to tackle a raft of different implications rising from sudden loss of revenue.

Now the government of the day was going further and introducing competition into the domestic market. The trial for this initiative was the West of England and Welsh regions. A large number of suppliers and new entrants had announced their intention to compete and enter the market. Everyone of these had said that they would offer better quality at a cheaper price.

The local regional management team met in a competitive strategy session to discuss their course of action. The corporate board had given them the ability to adjust or discount price should they need to. They needed to work out how they would respond to this frightening and unusual onslaught.

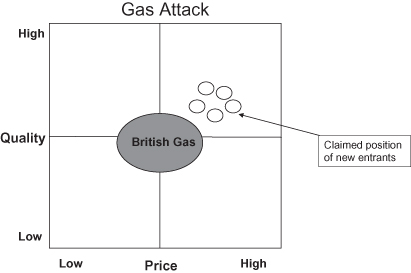

During a competitive strategy workshop they first worked through a “positioning map” (see separate entry) for their region and the strengths (and vulnerabilities) of a market leader. Like many companies they were more critical of their own firm’s capabilities than others. One iconic moment was when they realized that the few people in the room had, between them, several hundred years of experience in the gas market. They then broke into teams to examine and position all the competitors that had announced that they would participate in the trial. Every single one had claimed they would offer better quality at cheaper prices.

As one after another was placed at the same position on the map it became obvious that this was not sustainable. These new entrants would have to move their stance to gain a sufficient number of customers and they would trip over each other in fighting for the customers who said they might move supplier. (In the event that turned out to be true. There were appalling and, in some cases, corrupt practices as suppliers fought for the first customers. Several soon withdrew.) Back in the workshop the managers decided to behave like market leaders. They announced a series of packages which reinforced their own heritage and quality. They even made it easy for people to leave, arranging to say goodbye in a manner which made it clear that it would be easy to come back; and they did not take advantage of the price reduction mechanism offered by their board.

![]() RATING: Practical and powerful

RATING: Practical and powerful