Chapter 2. Using IDEFO for Process Improvement

In the commercial arena, Michael Hammer and Michael Champy have led the Business Process Reengineering movement in which companies revise their organizational and operating procedures to become lean and mean. In Reengineering the Corporation, Hammer and Champy focus on business processes, and advocate fundamental, radical, dramatic change (their three key words). The objective is to enable companies to survive in the competitive environment of the future.

Hammer and Champy’s approach requires a strong management team with solid support. Furthermore, the members of this team must be able to think inductively, more than deductively. That is, the team must be able to “first recognize a powerful solution and then seek the problems it might solve.”1

1 See Michael Hammer and Michael Champy, Reengineering the Corporation (New York: HarperBusiness, 1993), p. 84.

Though most commonly applied in the commercial arena, Hammer and Champy’s approach has also taken root in the government arena—most specifically in the Department of Defense (DoD).2 Motivated by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the need to downsize the military, the Bush Administration appointed Paul A. Strassmann Director of Defense Information and chartered him to accomplish a $350 billion reduction in the DoD budget over a five-year period. The Corporate Information Management (CIM) organization was formed as the new agency responsible for this government downsizing effort.

2 The actual jurisdiction of this work was under the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Command, Control, Communications and Intelligence (OASD/C3I). However, in this book, the distinction between OASD and DoD is not made, but the term DoD is used uniformly for both levels of reengineering effort.

Wanting the most effective nonproprietary method to accomplish his goal with minimum breakage,3 Strassmann championed widespread use of IDEFO by the DoD.

3 In this context, “breakage” is defined as time lost and expense incurred when attempting to implement a change.

Use of IDEFO in Support of BPR

The ICAM and ITT applications of SADT and IDEFO, described in the previous chapter, were early examples of Business Process Reengineering (BPR) enterprise analysis, although they weren’t called that at the time. From those experiences, the following observations were made about the fundamental criteria for applying IDEFO to support a successful reengineering effort:

Culture: An enterprise usually consists of many cultures.4 Each culture has a unique terminology or jargon that is key to understanding that culture. If the enterprise’s cultures do not communicate well between each other, a communication gap can arise.

4 By my definition, a culture consists of people with similar training and backgrounds who work together to provide their unique enterprise contribution. Examples of such cultures are accountants, engineers, secretaries, machinists, and so on.

Communication: The many different viewpoints of an enterprise need to be analyzed in order to understand, control, and change that enterprise effectively. The diverse cultures need to support each other and work together if the enterprise is to be successful. Support by one culture (for example, computer systems) requires an understanding of the needs of the foreign culture (for example, manufacturing). In addition, the support requirements must be communicated to management as well as between the staffs in both cultures if one culture is to effectively support another. To be able to control complexity, developers need to trace requirements from the user culture to solutions in the support culture.

Documentation: How an enterprise operates is typically recorded only in the heads of the experts who operate that enterprise, not in company manuals. Documentation is essential.

Graphics: Complexity can be understood if it is broken down into small enough pieces, with the interfaces between the pieces defined precisely. One-dimensional text-based descriptions are not adequate to convey an enterprise’s complexity or to communicate requirements; two-dimensional graphics are needed. A graphics-based model of the elements of an enterprise can serve as an effective communication and planning baseline.

Procedures: The application of the modeling method must be governed by proven basic principles and concepts, as well as by orderly and controlled procedures (pragmatics), or the effort will not be successful. To develop the graphics-based model, the staff must participate in its development, validate the details, and buy into any changes that result from the analysis.

Model template: Many enterprises have more in common with other enterprises than they realize; often, a broadly applicable model of a class of enterprise can be reused to save time and budget.

After the early BPR applications on the ICAM and ITT programs, the IDEFO method was used primarily by the aerospace industry and the Air Force to analyze and plan modernization efforts. However, its utility for reorganizing and improving the total enterprise was recognized but not capitalized on by the user community until the Department of Defense applied it in its own reorganization and downsizing.

Use of IDEFO for Military Downsizing and Reorganization

The great potential of IDEFO was articulated by Strassmann in his keynote presentation to the IDEF Users Group in Washington, D.C., in October, 1992. Speaking before more than four hundred government and industrial managers, Strassmann noted that the United States is moving “from an industrial civilization to an information civilization,” and that while during the past two hundred years the nation had experienced an astounding productivity growth, progress had stagnated in the preceding decade. Tracing one cause of this stagnation to unreasonably large overhead costs, Strassmann observed that the overhead labor and managerial province had not been subject to the kind of “meticulous examination” that technology had experienced during the same decade. He noted further that personal taxes, which have been cited as a great burden at 35 to 40 percent, pale in comparison with the enormous burden American business bears in its overhead, which typically ranges from 40 to 80 percent. Strassmann reported his goal: to reduce the overhead and management costs of the “checkers, auditors, lawyers, coordinators, procedure writers. . . . The people who check the checkers are a tax upon it.”

Strassmann advocated a form of BPR that is tailored to government needs and that fits into the DoD environment. Furthermore, he cited IDEFO as the only analysis method that had achieved the record of success required for understanding and controlling an Information Age enterprise.

Instead of applying Hammer and Champy’s concept of Business Process Reengineering—of fundamental, radical, dramatic change—the Department of Defense had to make use of existing or so-called legacy systems (to relocate personnel, for example) or to convert existing facilities for new purposes (for example, converting a military base into an airport or a prison). This involved an analysis of present operations (the AS-IS picture) before detailing the picture of future operations (the TO-BE picture).

Although some BPR proponents argue against analyzing the current enterprise, saying that we should strike out in new directions, the DoD could not afford this luxury to the extent that a commercial enterprise could. BPR proponents are right that we must not get stuck automating the old manual ways of running the operation, but it is essential that we see how the current operation can be evolved into the new operation. There must be a solid, inductively reasoned vision of the future operation that is not encumbered by old ways, but there also must be a clear path from here to there. That path depends on knowing precisely how the enterprise works now. However, this approach of modeling the current system has several inherent dangers:

![]() The analysis of the AS-IS picture may become bogged down and the objective inadvertently changed to one of automating the present operation.

The analysis of the AS-IS picture may become bogged down and the objective inadvertently changed to one of automating the present operation.

![]() The enterprise may lack a strong leader to drive the development of the TO-BE operation, or there may not be a key cadre of managers and staff supporting the leader’s effort, top down and bottom up.

The enterprise may lack a strong leader to drive the development of the TO-BE operation, or there may not be a key cadre of managers and staff supporting the leader’s effort, top down and bottom up.

![]() The enterprise reengineering process may not include enough tasks that can be performed by the large number of people involved in the reengineering project.

The enterprise reengineering process may not include enough tasks that can be performed by the large number of people involved in the reengineering project.

The reengineering process employed by the DoD required well-thought-out steps and stages, with carefully devised roles for all project members. IDEFO models used in such a process must reflect the same inductive reasoning described by Hammer and Champy (for example, “IDEFO is the method—now where can it best be used to accomplish the goals of the effort?”).

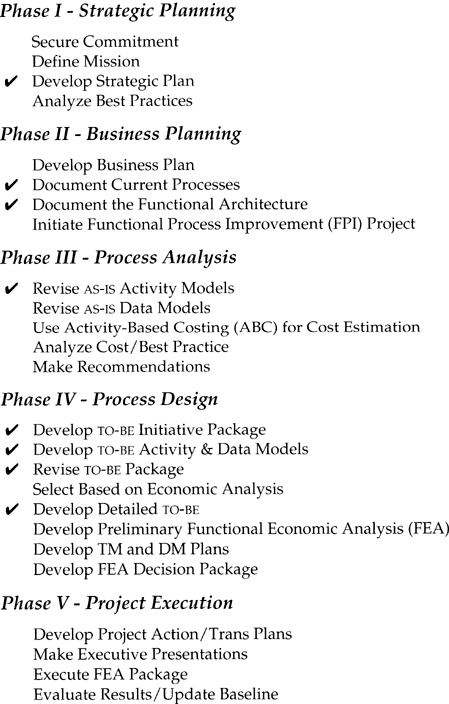

IDEFO is at the heart of the DoD’s version of Business Process Reengineering. The DoD’s BPR procedure, as originated by the CIM office, is an example of a well-defined method that prescribes specific models to be developed and provides a description of the use for each model once it is completed.

Although currently undergoing revision, the basic CIM process is summarized in Table 2-1. The eight steps in which use of the IDEFO models is specifically prescribed are noted by a checkmark.

Benefits of Using IDEFO Models for Enterprise Reengineering

Having worked on commercial BPR projects and having applied the DoD’s BPR process for several years, I have seen substantial evidence of the benefits that IDEFO brings to any reengineering effort. Overall, this positive feedback amounts to more than that received after similar use of SADT since its inception. Even still, at the completion of a BPR project, enterprise management typically asks: What is the benefit of using IDEFO when the information could have been obtained by interviewing the experts and identifying those things that need improvement?

This is a reasonable question to ask: Is it worth the time and expense, including all of the training and paperwork? It is true that improvements in an enterprise can be specified in English, without any graphics, and simple improvements have indeed been defined and implemented using English only. However, the more complex the enterprise, the more far-reaching the effects of a change—and, the more complex the enterprise, the more the staff members must document their area of expertise and the more misunderstandings will arise in defining a change. There is a consensus today that the use of a graphical language approach such as IDEFO reduces misunderstandings and facilitates the main objective: change control and planning.

Clearly, the software industry has been developing systems for a sufficiently long period that the effect of a graphical design language on the quality of the resulting system has been seen. Since the 1970’s, when graphical design languages came into vogue, statistics show that computer systems designed with textual requirements and textual design alone contain more than twice the number of errors and oversights than comparable systems designed using a graphical language (any graphical language—it doesn’t seem to make a difference which one is used).

The same effect should apply to the enterprise reengineering experience. Yes, the enterprise may be redesigned using only textual descriptions of the improvements, but that will result in considerably more breakage when the resulting change is implemented into daily enterprise operations. The effect is unavoidable, not because the staff implementing the change is not careful or sufficiently knowledgeable, but because the complexity of the operation and the impacts of the change are just not evident without a graphical model of the enterprise.

So far, this discussion of IDEFO has focused on the graphical language alone. In itself, graphical expression is a major aid in enterprise reengineering, but the benefits can be further leveraged with a well-designed engineering discipline. Engineering methods verify the correctness and completeness of the facts portrayed by the model, and they examine a level of detail that usually resides only in the heads of the staff.

Taking into consideration Hammer and Champy’s concept of inductive reasoning, as well as the twenty-five DoD/CIM steps for running a BPR project, let’s look at how the IDEFO method can be used to support BPR efforts. Properly used, an IDEFO modeling effort uncovers and documents the processes of an enterprise in a more precise format and comprehensive scope than any other popular modeling method available today. For an AS-IS model, the IDEFO reader/author critique procedure validates the correctness and completeness of the model’s facts; for a TO-BE model, the method provides the planning staff with a means of defining improved processes and a way of gaining consensus and common understanding among the management of the enterprise.

An AS-IS IDEFO model of an enterprise cannot help but uncover obvious improvements that are simple to implement and that provide an immediate return on investment, which often can justify the modeling expense by itself. The argument is that once management sees precisely how the enterprise actually operates, it finally has the needed information to tune the operation, rather than rely on the “everything is under control” picture painted by subordinates who do not want to make waves.

These improvements are the low hanging fruit, but are not the total of the benefits. To get the most return from an IDEFO model, one must insure that the purpose for creating the model is well defined. The general rule is: Never create a model for the purpose of creating a model. To do so would indicate a lack of vision on the part of management. The obvious improvements resulting from developing the model will be achieved anyway; the project needs a more focused purpose. To achieve this, we write the purpose statement (required on the top-most diagram of the model) in the form, “This model will be used to. . .” By following this format, we assume that the purpose statement defines how the model will be used once it is completed. Note that the manager of the modeling project should thus relate the model’s usage purpose to the project plan task structure.

The following sections further describe the benefits of the reader/author cycle, the workshop approach, and the AS-IS modeling process.

The Reader/Author Cycle and the Workshop Approach

Two major methods of gaining consensus and critiquing the content of an IDEFO model are currently employed: the reader/author (R/A) cycle and the workshop. The R/A cycle is the original approach used on SADT projects, and the workshop is a subsequent approach developed by the DoD for reorganizing government enterprises.

Neither method is likely to be wholly successful: The R/A cycle may bog down if individual reviewers do not provide in-depth review on their own volition; the workshop sessions involve user experts in defining requirements, but they can be prohibitively expensive and may leave insufficient time for the IDEFO author to perform the actual analysis.

In the second case, the IDEFO author may spend 100 percent of his time documenting what the workshop attendees are describing, leaving him no time whatso-ever to practice the skill for which he was trained—analysis of systems. The work-shop format can force use of the IDEFO language for documentation, not for analysis, a situation analogous to that in which an author is asked to write a book by committee. The resulting work lacks the insight of a single author and does not flow as smoothly as when the author is free to practice his trade without interference.

On the other hand, the single-author R/A cycle method has the disadvantage that important consulting-expert opinion might be missed, or that a thorough evaluation of the model might not be accomplished because busy people can’t take the time to respond to a request for a written critique (as required by the R/A cycle). The danger is that consensus and buy-in by the management and staff may not be achieved.

A solution would be to combine the best of both methods into a new scheme that gives the author a chance to use his talents and yet achieves the enterprise consensus required for follow-through implementation. In this combined approach, the IDEFO author would interview key management personnel to gain overview insight into the operation of the enterprise from management’s perspective, and he would also hold workshops for the staff to define the actual process detail to make the model real and not just conjecture. The staff workshops would not be full-day information-gathering sessions, but would begin with half-day sessions and a strawman model developed by the author from prior interviews and documentation.5 Since management would not be invited to the staff workshops, the staff would be free to modify the model to reflect reality.

5 A “strawman” is a draft created as a talking point for a group session. It is expected to include inaccuracies, but it serves to focus discussion on specifics rather than generalities.

This approach avoids the awkward and difficult job of trying to get the staff to provide the big picture of the enterprise—a critical modeling level that can only be developed from the perspective of top management. At present, the development of this part of the model in workshop mode with only the staff present meets with impatience and a “Why are we wasting our time with this? We need to get down to the details” attitude.

By attending half-day workshops rather than full-day sessions, staff members are not away from their daily duties for long periods of time and the cost due to work interruption is reduced—a clear benefit. Most important, half-day sessions give the IDEFO author a chance to think about what he is analyzing and to apply his analysis skills—a critical element of the BPR workshop approach that is missing from the continuous session workshop approach practiced at so many sites.

Following the interview and workshop sessions, the author creates the model and writes the accompanying text (which, under present IDEFO working rules, he must do during the meeting). The improvement opportunities are documented as part of the text that accompanies each diagram, thus focusing the reengineering effort on the findings of the modeling effort.

The major deliverable, or work product, of the BPR project consists of a set of precise, accurate, communicative improvements described in graphical and textual form. These improvements mirror the knowledge of the group that created and reviewed the AS-IS model and the farsightedness of the group that developed the TO-BE IDEFO model. The remaining effort is to develop and follow through on the plans to implement the improvements, in an orderly fashion, and with minimum breakage to the enterprise’s viability to function during the change-over period.

IDEFO models are not created for the sake of creating models—they each have a well-defined purpose in the overall BPR effort. They represent a valuable language with which to express ideas to the critical personnel of the enterprise who themselves are involved with the planning and implementation of the change.

Consider, for example, an enterprise and its past attempts to manage change and implement improvements using text and the block diagram approach characteristic of structured analysis and data-oriented analysis. The traditional planning documentation is too verbose and difficult to follow. When changes are implemented, there is considerable breakage, and it takes a great deal of time and money to get things working smoothly again. From the human-factors perspective, implementation of the changes typically takes a strong management push. Buy-in by the staff is pursued, but the fortitude and persistence of management is the key factor in accomplishing the change.

By using IDEFO, one can better understand, communicate, and validate the proposed changes. The graphical language makes concepts easier to understand and communicate. The staff, who is familiar with the details, can evaluate the portion of the model it is most familiar with; management can study the higher-level diagrams to understand the big picture.

To sum up, then, the primary benefit of the use of IDEFO for BPR is: the ability to manage change. This ability is the key to overcoming the chief roadblock to implementing BPR improvement, since effective change management results in lower cost and less breakage. If computer system design experience can be used as an analogous measuring stick, then approximately 50 percent of the errors and oversights should be avoided—a very significant cost- and time-saving benefit.6

6 This section has provided a management-oriented discussion of benefits; for a technical discussion, see Chapter 3.

The AS-IS Model

Analysts are often asked: “What is the value of developing an AS-IS model? Why not just model the TO-BE picture of how we envision the improved enterprise?” The following brief stories illustrate the value of AS-IS modeling:

A large manufacturer attempted to implement a parts-tracking system to comply with a stringent new government requirement. After an investment of six million dollars and more than a year of development, the new system was ready to go online.

The enterprise soon discovered that there had been significant misunderstanding by the new system’s developers regarding information currently being conveyed manually. The cause was the lack of in-depth understanding of the AS-IS picture of the manufacturing operation. In this case, a daily phone call passed important information between the scheduling staff and the shop floor, but because this key communication path was not documented in the company’s manuals and because no AS-IS analysis had been performed, the passing of information was overlooked when the new computerized system was built. The system had to be scrapped.

Having learned a costly lesson, the manager of the new system development project became an IDEFO convert and manager of the SADT/IDEFO analysis organization, claiming that he would never again fall for the trap of building a new system with insufficient information about the AS-IS operation.

At another company, strategic planners welcomed the introduction of IDEFO, since they had been through what they considered to be the typical sequence of system-development events, as follows:

Step 1: Plan the introduction of a manufacturing process improvement effort, including a budget for AS-IS analysis.

Step 2: Buy equipment, experiment with the new process, and begin building pieces of the new system.

Step 3: Experience overruns, discover hidden costs, and reestimate the job’s cost and schedule.

Step 4: Cut the budget for AS-IS analysis, and increase the implementation funds.

Step 5: Spend several times the AS-IS analysis’s original budget patching and getting the improvement to work properly, with a typical one-year schedule slippage.

Step 6: Return to Step 1 with the next improvement idea.

In this second company, the IDEFO method of developing an AS-IS model was applied to one area only, as an experiment to evaluate the value of the approach. As the model was developed, it was used to reveal several significant oversights in meetings with management. In addition, analysis of the AS-IS operation brought out several other simple improvements that were subsequently approved by management.

Unfortunately, the remaining budget for IDEFO AS-IS analysis was soon required to cover the overruns in the other areas. The areas in the improvement project that were not using IDEFO methods had grossly exceeded their budgets. The IDEFO-based experiment was terminated. Yet another company had fallen into the old trap! Again, the major problem was a lack of management support for the IDEFO analysis.

Additional horror stories abound, but here are a few examples from my own experience that show the positive effect of using IDEFO. These cases present four different kinds of BPR improvement:

Case 1: using IDEFO to facilitate needed information flow between accounting and project management

Case 2: using IDEFO to reduce the cost of government proposal development

Case 3: using IDEFO to analyze poor performance of a company’s field office

Case 4: using IDEFO to introduce new business process concepts, such as Total Quality Management and agile manufacturing

Case 1: Facilitate Information Flow

The problem, as stated to enterprise management, was that project expenses were not being controlled properly. Examples of cost overruns were common, and project managers blamed this on the lateness and inaccuracy of project cost reports provided by the enterprise’s accounting department. In addition, small contracts frequently encountered additional costs several months after the contract was closed, due to late processing of expenses. This resulted in embarrassing calls to customers to ask them to make unexpected additional payments, or in costly absorption of these expenses by the enterprise.

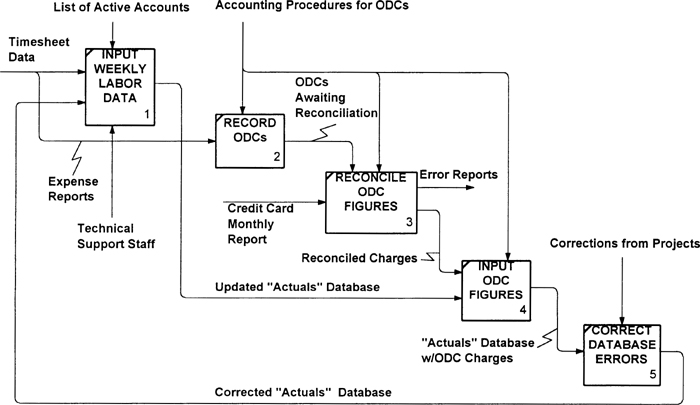

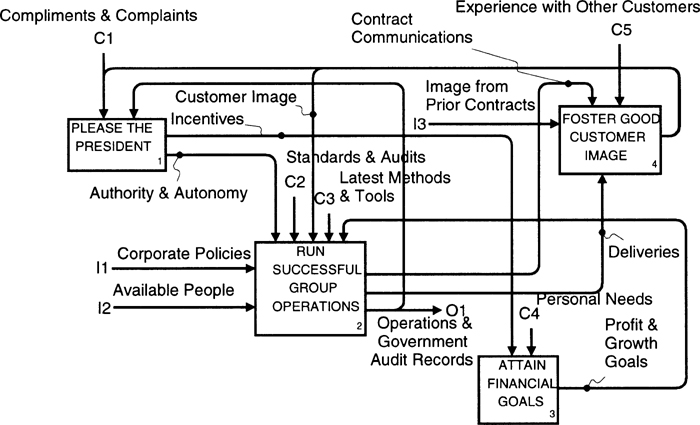

Clearly, the accounting department’s processing of expenses had to be faster and the accuracy of the records improved. To pin down the causes of the problem and to determine which changes would be effective, we analyzed the enterprise in the area of the accounting department’s processes. The complete model developed as part of this analysis is presented in Appendix B (Sample Models). As an illustration, a diagram that identifies one source of delay is reproduced here.

In the diagram, boxes 2, 3, and 4 show the process of handling the expense reports (in accounting terms, Other Direct Charges or ODCs) turned in by the project staff. When an Expense Report is turned in (see box 2, input 1), the data are recorded in the company’s accounting system. No reports on expenses are provided to the project manager until actual payment is made for all items on the expense report, including air fares (this policy is the result of a DoD regulation designed to reduce efforts on corrections when trips are changed). Payment is therefore triggered by the receipt of the invoice for air fares on the monthly corporate credit-card account (see box 3, input 1). This notice may be received by the accounting department more than two months following the actual trip, due to billing cycles at the credit-card company. If discrepancies are encountered, further delays may be incurred while accounting staff members reconcile the data (see boxes 3). Finally, the ODC figures are entered into the company accounting system (see box 4). The information is then reported to the project manager in the next monthly contract accounting report, which may add nearly another full month to the delay.

The improvement sought by the IDEFO analysis was to reduce or eliminate the delays. This could be done by instigating an encumbrance accounting report to send to the project manager (a report generated as soon as the trip expense report is received at box 2), by eliminating the credit-card company billing service and performing this task in-house, or by processing air fares separately from other ODCs, since these will not change after the trip has occurred.

The TO-BE improvement selected was development of an encumbrance system, since any change in the contract with the credit-card company would have had a large ripple effect on other aspects of the company’s accounting process. Furthermore, the use of an encumbrance system had many other beneficial side effects, such as providing more timely financial information in other areas (not shown). The investigation into which improvement to select involved an in-depth analysis of the overall effect of each of the possible approaches, including whether a significant financial return on investment (ROI) would offset the cost of developing and converting to the new in-house system.

Case 2: Reduce Costs

The cost of developing government proposals has risen staggeringly over the past twenty years. Proposals now often exceed a thousand pages, and sheer volume gives rise to a considerable amount of waste in the proposal development effort. At one company we studied, these costs had increased overhead to the point where the enterprise was having difficulty remaining competitive.

As was done in Case 1 with the problem of improving accounting department cost reporting, we analyzed one aspect of the enterprise to identify how the proposal development process could be improved. Once a model of the marketing area had been decomposed to a fine level of detail, analysts interviewed the proposal development staff to solicit suggestions for improvement. The results of the interview were documented using the diagrams of the model to show specifically how the proposal development process would be run in the future. This information was then used to develop a TO-BE model of this area.

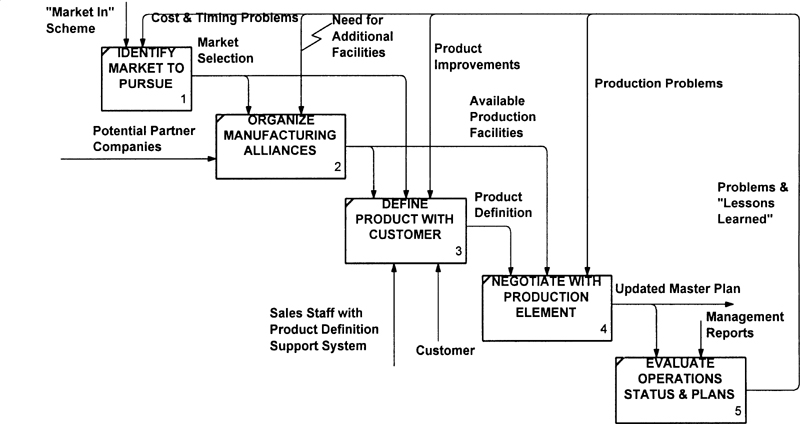

When modeling the proposal preparation process, the IDEFO author noted that each field office organized the proposal team differently. Some proposals included a coalition of subcontractors, whose contributions to the overall proposal were handled like a small proposal to the prime contractor. Whether or not there were subcontractors, the entire team typically met to discuss overall strategy and plan key proposal elements, based on the award factors presented in the government’s RFP. Figure 2-2 presents the resulting diagram: “Organize & Manage the Effort.”

The preponderance of problems typically occurred in the writing of individual proposal sections. Specifically, configuration management of the pieces of the proposal needed more careful attention. In this enterprise, all proposal documents were prepared using the services of a separate publications department. Often, the entire staff of the technical publications department would edit a single proposal’s text and artwork; changes to the same section were sometimes submitted by more than one person; and time would be lost in reworking the edits of inexperienced temporary staff.

Instead of modeling the AS-IS chaos—an activity that would have been difficult and unproductive—we decided to develop a configuration management (CM) process based on the company’s CM support tool and the know-how of the software development staff; the goal was to implement control procedures similar to those used to manage large software system source file databases. We determined that a control procedure must require check-out of proposal pieces and must restrict access until changes have been incorporated. Fortunately, the CM of software source programs had an existing IDEFO model as a starting point (see Appendix B).

Case 3: Analyze Performance

The same enterprise had operated at a loss in a few of its field offices for several years but was unable to determine how to reverse the trend. Examination of the generic enterprise model did not provide any help in identifying where additional modeling could be used to uncover the source of the problem. Furthermore, there were no obvious technical or management problems that made one field office less profitable than another.

The problem was suspected to be caused by human factors, since it was well known that staff members at the troubled field offices had neither good working relationships with each other nor a good image with their customers. Analysts had for years thrown up their hands and declared that these factors were impossible to diagnose since they were not susceptible to logical cause-and-effect analysis.

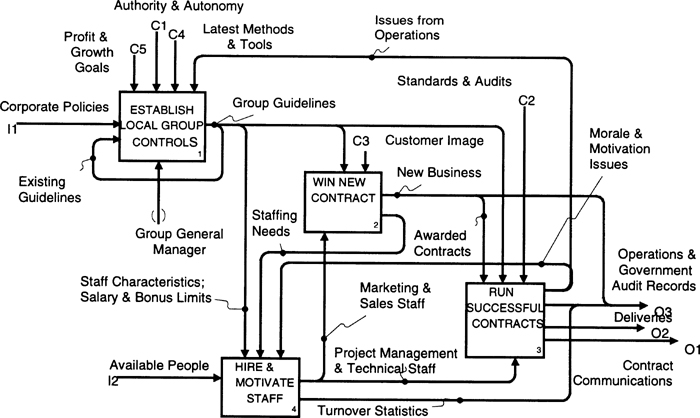

However, the IDEFO method allows analysts to adopt a viewpoint that controls which aspects of the model to include or exclude, and that allows them to determine which activities to emphasize. The analysts decided to model the field office operation from a human-factors viewpoint, emphasizing the activities that relate to public image, customer relations, and working relationships. Figure 2-3, titled “Develop Company’s Public Image,” was the result of the human-factors modeling effort.

The figure shows that six activities were selected, beginning with the staff’s becoming known to the government program office through the efforts of the enterprise’s marketing staff (see box 1). The technical staff supports the marketing staff when called on to speak to a selected audience at the program office. When an RFP is issued by the program office, the enterprise has its next opportunity to make an impression by pursuing the proposal submitted by the enterprise (see box 2).

If the enterprise is awarded the contract, the technical staff develops the product prescribed in the contract (see box 3), and produces the resulting Delivered Product, which then leaves an impression with staff at the government program office when they start using the product. An impression is also made during the product development effort, through the many telephone calls, draft deliverables, manager-to-manager conversations, and financial interchanges (see box 5). By the time the contract has run its course, the program office will have this experience to compare with that of working with many other contractors, and undoubtedly it will know whether the enterprise is easy to work with or not.

So many of the impressions made by the entire enterprise have to do with individual staff members—in the way they comport themselves, how well they communicate with each other and the program office staff, and so on—that a sixth box (HIRE STAFF) was added to the diagram. This staff-hiring function provides the project with staff, keeping details of each office’s staff qualifications for reference when interviewing and selecting candidates.

To evaluate each field office, we added values for each of the data interface arrows on the diagram. The field offices that were having trouble had values such as “hard to work with” (output of box 5) and “large; slow response; not very user-friendly products” (output of box 4). The surprising result was the clear difference in “staff qualities.” Those field offices that were having image problems had not focused on qualities such as “ability to work together,” “ability to communicate,” or “ability to make good presentations.” They instead had focused too heavily on technical excellence.

As it turned out, the overemphasis on technical quality resulted in a staff that formed cliques and lacked respect for their customers’ business issues and human factors. Their only interest was technical excellence, and they were not concerned if they appeared abrasive when talking to the customer.

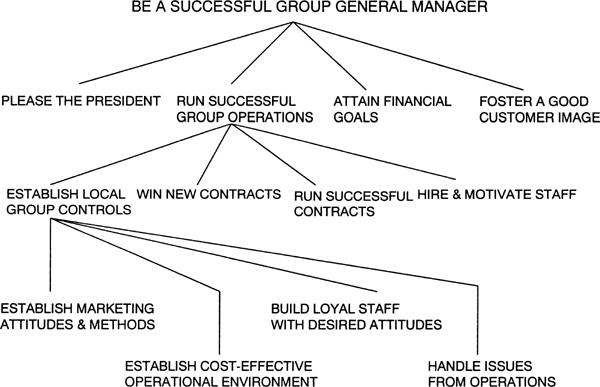

Once the hiring-criteria problem was corrected, the enterprise’s management decided that an additional IDEFO model would be useful to ensure proper interfacing between headquarters and the field offices. This new model, again to be prepared from a human-factors viewpoint, would emphasize the activities that motivated field office managers, and would reveal what effect these motivators had on how managers run an office. In this way of thinking, guided by the model, field office managers were motivated to seek continual improvement as well as improved communication with top management at headquarters.

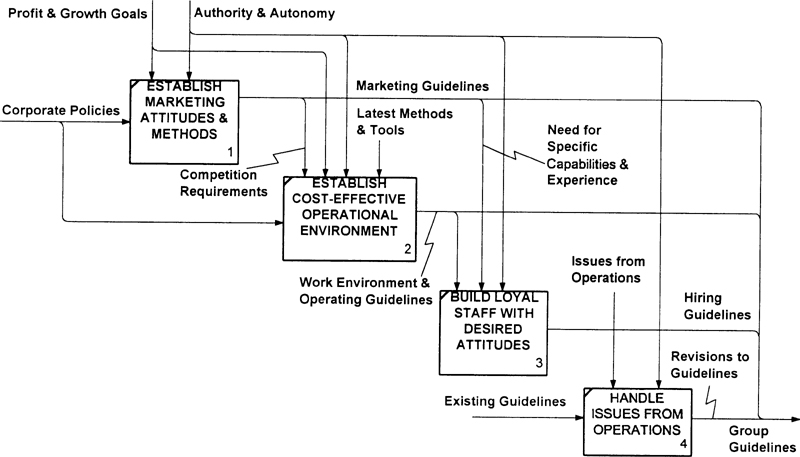

The model that resulted from this effort was used to plan management incentives, including objective success criteria for the operations under each manager’s control. The diagrams on the following pages show the structure of the model (its node diagram), followed by the next three top levels of the model, called the motivational factor models (or “MOT,” for motivation).

Case 4: Introduce Business Process Concepts

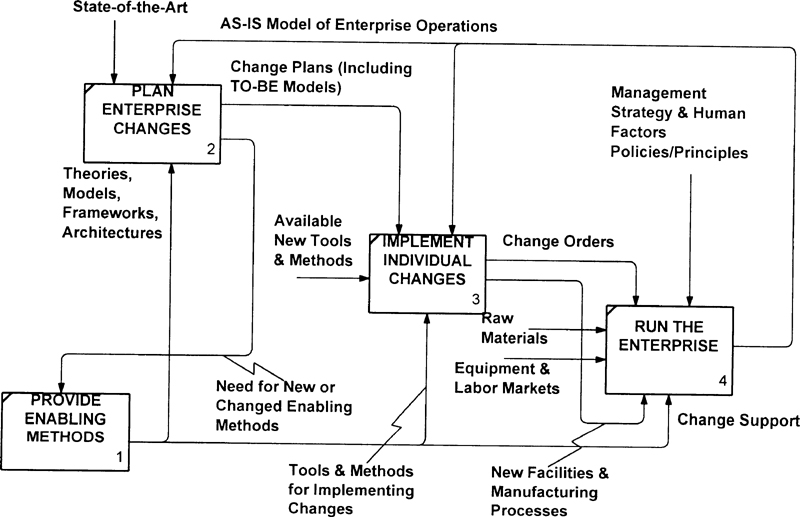

In order to create a Total Quality Management (TQM) program, each staff member in the enterprise was asked to think about ways that the material and information received from suppliers could be improved and about ways that the products to customers could be improved. Before this program could be implemented and operate effectively, the process needed an infrastructure, such as organizational entities with defined responsibilities and authority, channels for communicating recommendations and keeping the staff informed of progress, measurement of effectiveness of improvements, and evidence of appreciation for good suggestions from staff members. This infrastructure was modeled by showing a new environment at the top of the original model.7 In this new environment, the continual review of suggestions was shown, along with the change-planning activity, the provision for upgrading the enabling methods, and the tools required to operate in a more efficient manner (see Figure 2-8, “Evolve the Enterprise Over Time”). Figure 2-9, the final item in the set, is a TO-BE diagram detailing the five new management functions envisioned.

7 The term “environment” is the SADT concept that any model fits into a bigger picture. The author determines the bounds of the model—what is included and what is outside the model’s scope. The top of the model defines the model’s interfaces to the world outside the scope of the model, known as its environment.

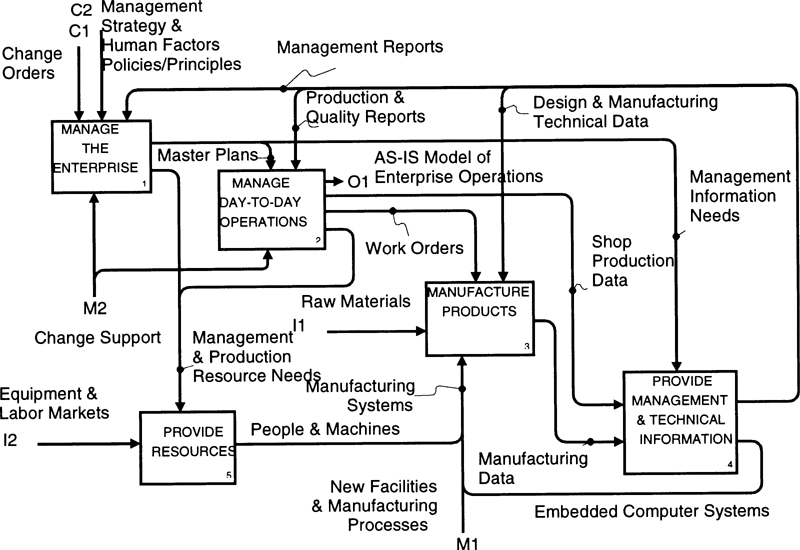

The enterprise next defined a new management concept to make itself more flexible, agile, and ready to respond to sudden changes in strategy from international competitors. This new picture of top enterprise management was captured in a TO-BE model showing the new flexible management structure (see Figure 2-10, “Manage the Enterprise”).

Boxes 2, 3, and 4 in Figure 2-10 represent newly defined TO-BE management functions. These activities are designed to discard the concept of developing the entire product within the company and, instead, employ the more flexible approach of purchasing product parts from outside suppliers at the best possible international market price.

To control its own destiny while still producing a better product with high customer demand, the enterprise worked with the customer to define the next generation product. A decomposition of box 3 would show how this works. Once this product definition—with new customer features—has been completed, negotiations with various component suppliers are conducted (see box 4). Alternative sources of components may be sought, and small, trial production runs done until the market has been fully tested and the product durability and usability evaluated (see box 5).

The detailed decomposition of these major activities is not presented here. The idea is to illustrate how IDEFO might be used in a TO-BE environment with a commercial enterprise to adopt a new approach to mapping its future. The example is based upon a real case: One of the Japanese automobile manufacturers has demonstrated that, by using the “large number of suppliers” approach, it can produce better-quality automobiles and can introduce new features to meet market demands more rapidly than its United States competitors. In addition, the Japanese manufacturer currently turns out the same number of cars with a fraction of the full-time staff of its United States counterparts, and it ensures a flexible structure by renegotiating with suppliers when new, higher-quality product components are available on the market. This approach is less cumbersome, less costly, and less time-consuming than the retooling required when the entire auto is fabricated and assembled by the parent company.

Conclusions from Commercial and DoD BPR Efforts to Date

Prominent consultants in both commercial and government arenas agree that there are two main roadblocks to achieving successful BPR. First, there is the difficulty of gaining and maintaining management commitment to BPR; second, there is the difficulty of effecting the required change in the culture of an enterprise.8 To these I would add an additional roadblock that crops up following the initial BPR analysis: the difficulty of implementing the resulting changes at minimum cost and with minimum breakage.

8 At the 1993 IDEF Users Group Conference, John Zachman made the point that change will never be implemented unless management can see that the pain resulting from not implementing the change exceeds the pain encountered in making the change.

An interview with a top official at one of the large accounting firms confirms my contention. Our company was considering entering into an alliance with the accounting firm to implement pieces of Reengineered Enterprises (our expertise was in the areas of system integration, computer facility downsizing, and software system development). The accounting firm official would not consider our proposition since, in his words, “we have our hands full already with what we’ve got. Besides, our business is to develop the BPR document and then get out before taking on the hard part of implementing the results.” He further went on to say that the potential for failure, cost overruns, encountering unforeseen problems, and so on, was too great a risk. His firm was happy with producing the recommendations and then getting out before they got into trouble by implementing anything.

The difficulty in implementing BPR changes was further emphasized by the president of a prominent software development assessment firm. This firm is one of the eight assessment specialist companies originally certified by the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) to perform assessments on software developers, using the government-sponsored SEI assessment procedure. After conducting assessments of more than twenty diverse software developers, the assessment firm observed that the majority of these evaluated companies did not follow through by implementing the recommended changes. The difficulty of implementing the changes soon became the assessment firm’s focus, and it selected the IDEFO methods to model implementation planning. The method was determined to be the best means of defining and obtaining buy-in on the specific changes and how they would be implemented.

If the human-factors roadblocks can be overcome, then the probability of successful BPR projects can be significantly increased. The IDEFO approach, when properly applied by experienced analysts as a supporting method and expressive medium to bridge the communication gap, can accomplish great changes.9

9 For a thorough analysis of the human factors, see Prof. John P. Kotter’s article entitled “Why Transformation Efforts Fail” (Harvard Business Review, March/April 1995).