9 ASC 250 ACCOUNTING CHANGES AND ERROR CORRECTIONS

Summary of Accounting Changes and Error Corrections

Change in Accounting Principle

Example of retrospective application of a new accounting principle

Example of change from FIFO to LIFO

Example Note A: Change in method of accounting for inventories

Disclosure of Prospective Changes in GAAP

Disclosing the impact of newly established GAAP that has not yet become effective

Example of a change in accounting estimate

Example Note A: Change in accounting estimate

Example of a change in accounting estimate

Change in Accounting Estimate Effected by a Change in Accounting Principle

Example of a Prior Period Adjustment

Evaluating Uncorrected Misstatements

Misstatements from prior years

Interim Reporting Considerations

Disclosures about events subsequent to the date of the statement of financial position

PERSPECTIVE AND ISSUES

Subtopics

ASC 250, Accounting Changes and Error Corrections, contains one subtopic:

ASC 250-10, Overall, which:

- Provides guidance on accounting for and reporting on accounting changes and error corrections

- Requires, unless impractical, retrospective application of a change in accounting principle

- Provides guidance on when retrospective application is impractical and how to report on the impracticability.

- Specifies the method of treating error correction in comparative statements

- Specifies the disclosures required upon restatement of previously issued statements of income

- Recommends methods of presentation of historical, statistical-type financial summaries affect by error corrections.

(ASC 250-10-5-5)

Scope

ASC 250 applies to all entities' financial statements and summaries of information that reflect an accounting period affected by accounting change or error.

Overview

Under US GAAP, management is granted the flexibility of choosing between or among certain alternative methods of accounting for the same economic transactions, Examples of the availability of such choices are provided throughout this publication, in such diverse areas as alternative cost-flow assumptions used to account for inventory and cost of sales, different methods of depreciating long-lived assets, and varying methods of identifying operating segments. The professional literature (in the areas of accounting principles, auditing standards, quality control standards, and professional ethics) is emphatic that, in choosing among the various alternatives, management is to select principles and apply them in a manner that results in financial statements that faithfully represent economic substance over form and that are fully transparent to the user.

Changes in accounting can be necessitated over time due to changes in the assumptions and estimates underlying the application of accounting principles and methods of applying them, changes in the principles defined as acceptable by a standards-setting authority, or other types of changes.

Changes in the accounting for given transactions can have a profound influence on investing and operational decisions. Financial statement analysts and management decision makers both generally presume the consistency and comparability of financial statements across periods and among entities within industry groupings. Any type of accounting change potentially can create inconsistency. The challenge is to present the effects of the change in a manner that is most readily comprehended by users of financial statements, who may impose various adjustments of their own in their efforts to make the information comparable for analysis purposes.

When contemplating a potential change in accounting principle, a primary focus of management should be to consider its effect on financial statement comparability. This should not, however, dissuade preparers from adopting preferable accounting standards, where otherwise warranted.

ASC 250 contains the underlying presumption that in preparing financial statements an accounting principle, once adopted, should not be changed in accounting for events and transactions of a similar type. This consistent use of accounting principles is intended to enhance the utility of financial statements. The presumption that a reporting entity should not change an accounting principle may be overcome only if management justifies the use of an alternative acceptable accounting principle on the basis that it is actually preferable.

ASC 250 does not provide a definition of preferability or criteria by which to make such assessments, so this remains a matter of professional judgment. What is preferable for one industry or company is not necessarily considered preferable for another.

Technical Alert

ASU 2012-04, Technical Corrections and Improvements, issued in October 2012 amended ASC 250-10-50-5 to clarifiy that “the disclosure provisions for a change in accounting estimate are not required for revisions resulting from a change in valuation technique used to measure fair value or its application when the resulting measurement is fair value in accordance with Topic 820.” This narrowing of the scope exception brings the Codification into alignment with the legacy literature of FAS No. 157, Fair Value Measurements, that provided the disclosure relief.

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

Source: ASC 250-10-20

Accounting Change. A change in an accounting principle, an accounting estimate, or the reporting entity. The correction of an error in previously issued financial statements is not an accounting change.

Change in Accounting Estimate. A change that has the effect of adjusting the carrying amount of an existing asset or liability or altering the subsequent accounting for existing or future assets or liabilities. A change in accounting estimate is a necessary consequence of the assessment, in conjunction with the periodic presentation of financial statements, of the present status and expected future benefits and obligations associated with assets and liabilities. Changes in accounting estimates result from new information. Examples of items for which estimates are necessary are uncollectible receivables, inventory obsolescence, service lives and salvage values of depreciable assets, and warranty obligations.

Change in Accounting Estimate Effected by a Change in Accounting Principle. A change in accounting estimate that is inseparable from the effect of a related change in accounting principle. An example of a change in estimate effected by a change in principle is a change in the method of depreciation, amortization, or depletion for long-lived, nonfinancial assets.

Change in Accounting Principle. A change from one generally accepted accounting principle to another generally accepted accounting principle when there are two or more generally accepted accounting principles that apply or when the accounting principle formerly used is no longer generally accepted. A change in the method of applying an accounting principle also is considered a change in accounting principle.

Change in the Reporting Entity. A change that results in financial statements that, in effect, are those of a different reporting entity. A change in the reporting entity is limited mainly to the following:

- Presenting consolidated or combined financial statements in place of financial statements of individual entities

- Changing specific subsidiaries that make up the group of entities for which consolidated financial statements are presented

- Changing the entities included in combined financial statements.

Neither a business combination accounted for by the acquisition method nor the consolidation of a variable interest entity (VIE) pursuant to Topic 810 is a change in reporting entity.

Direct Effects of a Change in Accounting Principle. Those recognized changes in assets or liabilities necessary to effect a change in accounting principle. An example of a direct effect is an adjustment to an inventory balance to effect a change in inventory valuation method. Related changes, such as an effect on deferred income tax assets or liabilities or an impairment adjustment resulting from applying the lower-of-cost-or-market test to the adjusted inventory balance, also are examples of direct effects of a change in accounting principle.

Error in Previously Issued Financial Statements. An error in recognition, measurement, presentation, or disclosure in financial statements resulting from mathematical mistakes, mistakes in the application of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), or oversight or misuse of facts that existed at the time the financial statements were prepared. A change from an accounting principle that is not generally accepted to one that is generally accepted is a correction of an error.

Indirect Effects of a Change in Accounting Principle. Any changes to current or future cash flows of an entity that result from making a change in accounting principle that is applied retrospectively. An example of an indirect effect is a change in a nondiscretionary profit sharing or royalty payment that is based on a reported amount such as revenue or net income.

Restatement. The process of revising previously issued financial statements to reflect the correction of an error in those financial statements.

Retrospective Application. The application of a different accounting principle to one or more previously issued financial statements, or to the statement of financial position at the beginning of the current period, as if that principle had always been used, or a change to financial statements of prior accounting periods to present the financial statements of a new reporting entity as if it had existed in those prior years.

CONCEPTS, RULES, AND EXAMPLES

Accounting Changes

There are legitimate reasons why a reporting entity would change its accounting:

- Changing to an existing alternative accounting principle that management deems to be preferable to the one it is currently following

- Adopting a newly issued accounting principle

- Refining an estimate made in the past as a result of further experience and better information

- Correcting an error made in previously issued financial statements. Although technically not an “accounting change” as defined in GAAP literature, this involves restating previously issued financial statements and is also governed by ASC 250.

To facilitate accurate analysis, it is important for management of the reporting entity to adequately inform the financial statement users when one or more of these changes are made, and to provide sufficient information to enable the reader to distinguish the effects of the change from other factors affecting results of operations.

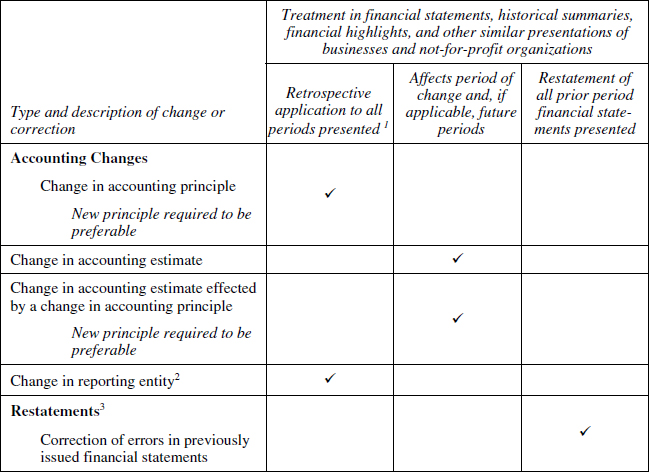

Each of the types of accounting changes and the proper treatment prescribed for them is summarized in the following chart and discussed in detail in the following sections.

Summary of Accounting Changes and Error Corrections

Change in Accounting Principle

Management is permitted to change from one generally accepted accounting principle to another only when

- It voluntarily decides to do so and can justify the use of the alternative accounting principle as being preferable to the principle currently being followed, or

- It is required to make the change as a result of a newly issued accounting pronouncement. (ASC 250-10-45-2)

Per ASC 250-45-1, the following are not considered a change in accounting principle:

- Initial adoption of an accounting principle.

- Adoption or modification of an accounting principle for transactions or events substantially different from previous transactions.

If a change in accounting principle is being made voluntarily, the financial statements of the period of change must include disclosure of the nature of and reason for the change and an explanation of why management believes the newly adopted accounting principle is preferable. This preferability assessment is required to be made from the perspective of financial reporting, and not solely from an income tax perspective. Thus, favorable income tax consequences alone do not justify making a change in financial reporting practices.

According to ASC 250, the term accounting principle includes not only the accounting principles and practices used by the reporting entity, but also its methods of applying them. A change in the components used to cost a firm's inventory is considered a change in accounting principle and, therefore, is only permitted when the new inventory costing method is preferable to the former method.

Preferability.

As stated, management is only permitted to voluntarily change the reporting entity's accounting principles when the newly employed principle is preferable to the principle it is replacing. The independent auditors are then charged with concurring with management's assessment. If the auditors do not believe management has provided reasonable justification for the change, AU-C §708.07 requires the auditors to express either a qualified or adverse opinion, depending on the materiality of the effects of the unacceptable accounting principle on the financial statements.

When management of a public company voluntarily changes the registrant's accounting principles, a letter from the registrant's independent public accountants is required to be filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). This “preferability letter” is to be included as an exhibit in 10-Q and 10-K filings (Regulation S-K Item 601, Exhibit 18) and must indicate whether the change in principle or practice (or method of applying that principle or practice) is to an acceptable alternative that, in the auditors' judgment, is preferable under the circumstances. (AsC 250-10-S99-4)

Retrospective application.

ASC 250-10-45-5 provides that changes in accounting principle be reflected in financial statements by retrospective application to all prior periods presented unless it is impracticable to do so. ASC 250-45-3 points out that as Accounting Standards Updates include specific provisions regarding transitioning to the new principles that are to be followed by adopting entities. The default method is retrospective restatement, whereas previously the default procedure was to recognize a cumulative effect adjustment in current results of operations. If FASB believes this to be the most beneficial method of transition, updates may still provide for adoption using cumulative effect adjustments,

Retrospective application is accomplished by the following steps:

At the beginning of the first period presented in the financial statements,

Step 1 Adjust the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities for the cumulative effect of changing to the new accounting principle on periods prior to those presented in the financial statements.

Step 2 Offset the effect of the adjustment in Step 1 (if any) by adjusting the opening balance of retained earnings (or other components of equity or net assets, as applicable to the reporting entity).

For each individual prior period that is presented in the financial statements,

Step 3 Adjust the financial statements for the effects of applying the new accounting principle to that specific period.

(ASC 250-10-45-5)

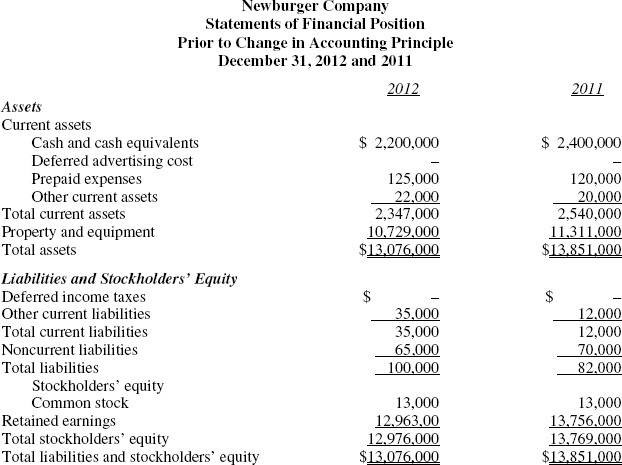

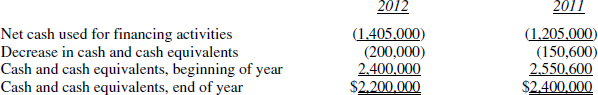

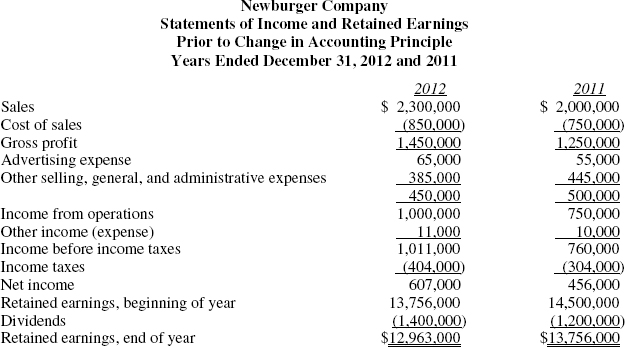

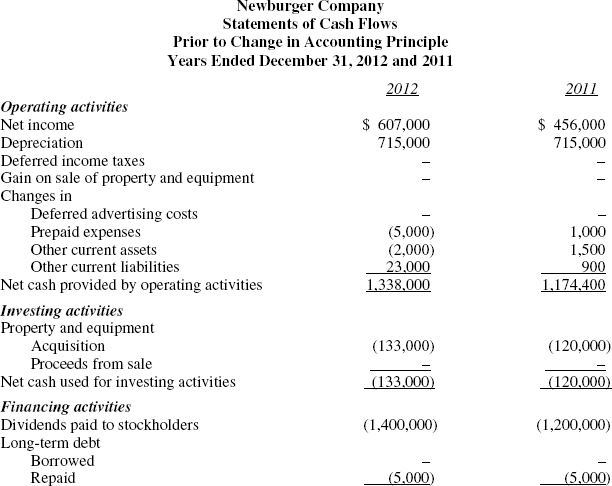

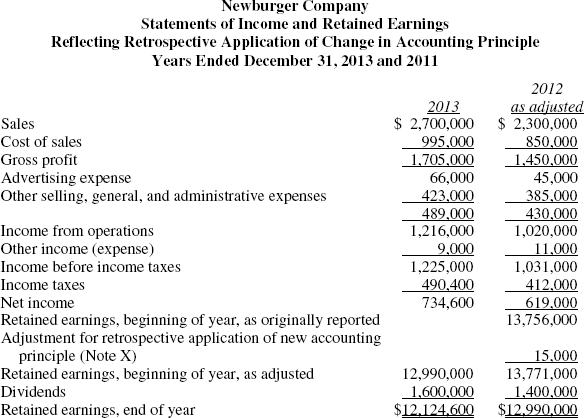

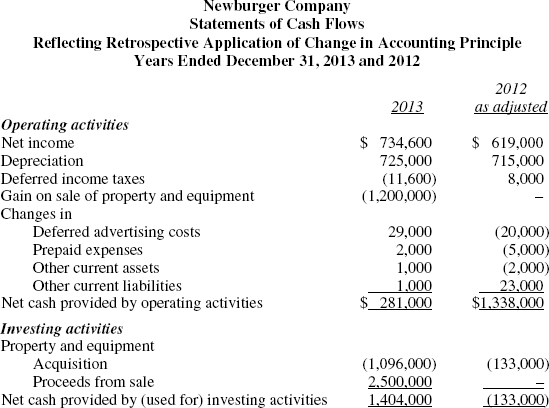

In 2001, upon the incorporation of Newburger Company, its management elected to recognize advertising costs as incurred. Newburger has been consistently following that policy in its financial statements. In 2013, Newburger's management reviewed its accounting policies and concluded that application of its current policy was resulting in substantial costs associated with the production of television advertising being recognized in financial reporting periods that preceded the periods in which the related revenues were earned. Consequently, management decided to change Newburger's policy to elect to expense advertising costs the first time the advertising takes place as permitted by ASC 720-35, Advertising Costs. Additional assumptions follow:

- As has been its policy in the past, Newburger plans to issue comparative financial statements presenting two years, 2013 and 2012.

- Newburger does not engage in direct-response advertising activities.

- A combined federal and state income tax rate of 40% was in effect for all relevant periods.

- Prior to the change in accounting principle, there were no temporary differences or loss carryforwards and, thus, there were no deferred income tax assets or liabilities.

- Advertising costs are deductible for income tax purposes when incurred and, therefore, upon adoption of the new accounting policy, Newburger will have a temporary difference between the book and income tax bases of its asset, deferred advertising costs. These advertising costs that are being recognized in the financial statements in the year after they are deducted on Newburger's income tax return represent a future taxable temporary difference that will give rise to a deferred income tax liability.

- The financial statements originally issued as of and for the years ended December 31, 2012 and 2011, prior to the adoption of the new accounting principle are presented below with advertising-related captions shown separately for illustrative purposes.

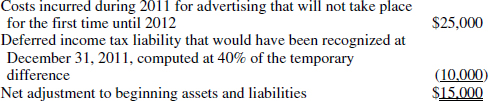

Step 1 Adjust the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities at the beginning of the first period presented in the financial statements (January 1, 2012, in this example). For the cumulative effect of changing to the new accounting principle on periods prior to those presented in the financial statements.

In this example, the preparer refers to the previously issued 2011 financial statements presented above. Assume the following data regarding advertising costs at December 31, 2011/January 1, 2012:

Step 2 Offset the effect of the adjustment in Step 1 by adjusting the opening balance of retained earnings (or other components of equity or net assets, as applicable to the reporting entity).

The $15,000 net effect of the adjustment in Step 1 is presented in the statement of income and retained earnings as an adjustment to the January 1, 2012 retained earnings as previously reported at December 31, 2011.

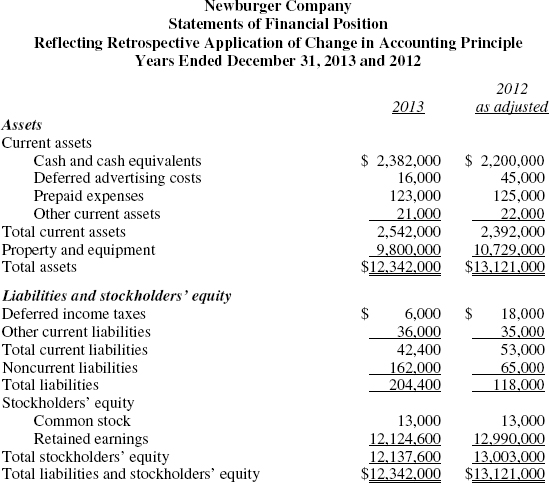

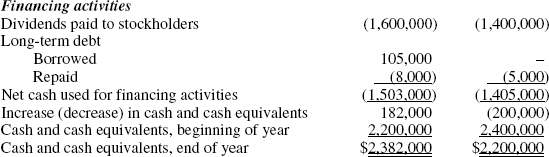

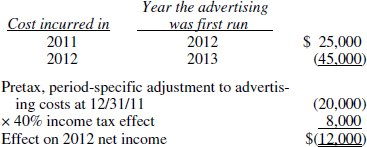

Step 3 Adjust the financial statements of each individual prior period presented for the effects of applying the new accounting principle to that specific period.

In this case, the following adjustments are necessary to adjust the 2012 financial statements for the period-specific effects of the change in accounting principle:

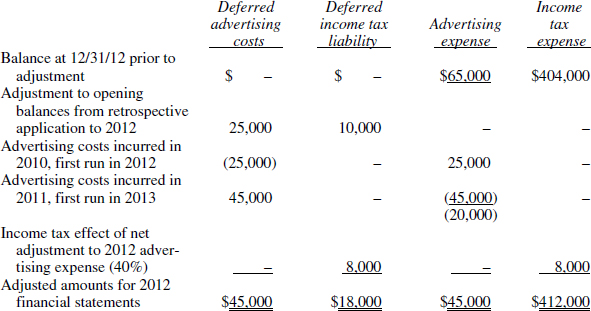

Adjustments to the 2012 financial statements for the period-specific effects of retrospective application of the new accounting principle are:

Adjustments to 2012 financial statements

The adjusted comparative financial statements, reflecting the retrospective application of the new accounting principle, follow.

It is important to note that, in presenting the previously issued financial statements for 2012, the caption “as adjusted” is included in the column heading. Prior to ASC 250, many preparers used the caption “as restated.” ASC 250 explicitly defines a restatement as a revision to previously issued financial statements to correct an error. Therefore, to avoid misleading the financial statement reader, use of the terms restatement or restated are to be limited to prior period adjustments to correct errors, as discussed later in this chapter.

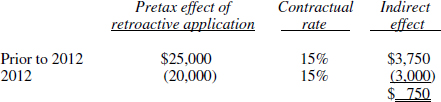

Indirect effects. The example above only reflects the direct effects of the change in accounting principle, net of the effect of income taxes. Changing accounting principles sometimes results in indirect effects from legal or contractual obligations of the reporting entity, such as profit sharing or royalty arrangements that contain monetary formulas based on amounts in the financial statements. In the preceding example, if Newburger Company had an incentive compensation plan that required it to contribute 15% of its pretax income to a pool to be distributed to its employees, the adoption of the new accounting policy would potentially require Newburger to provide additional contributions to the pool computed as:

Contracts and agreements are often silent regarding how such a change might affect amounts that were computed (and distributed) in prior years. Management of Newburger Company might have discretion over whether to make the additional contributions. Further, it would probably consider it undesirable to reduce the 2012 incentive compensation pool because of an accounting change of this nature, and it might thus decide for valid business reasons not to reduce the pool under these circumstances.

ASC 250 specifies that irrespective of whether the indirect effects arise from an explicit requirement in the agreement or are discretionary, if incurred they are to be recognized in the period in which the reporting entity makes the accounting change, which is 2013 in the example above.

Impracticability exception.

All prior periods presented in the financial statements are required to be adjusted for the retroactive application of the newly adopted accounting principle, unless it is impracticable to do so (ASC 250-10-45-9). FASB recognized that there are certain circumstances when there is a change in accounting principle when it will not be feasible to compute (1) the retroactive adjustment to the prior periods affected or (2) the period-specific adjustments relative to periods presented in the financial statements presented.

For management to assert that it is impracticable to retrospectively apply the new accounting principle, one or more of the following conditions must be present:

- Management has made a reasonable effort to determine the retrospective adjustment and is unable to do so.

- If it were to apply the new accounting principle retrospectively, management would be required to make assumptions regarding its intent in a prior period that would not be able to be independently substantiated.

- If it were to apply the new accounting principle retrospectively, management would be required to make significant estimates of amounts for which it is impossible to develop objective information that would have been available at the time the original financial statements for the prior period (or periods) were issued to provide evidence of circumstances that existed at that time regarding the amounts to be measured, recognized, and/or disclosed by retrospective application.

Inability to determine period-specific effects. If management is able to determine the adjustment to beginning retained earnings for the cumulative effect of applying the new accounting principle to periods prior to those presented in the financial statements, but is unable to determine the period-specific effects of the change on all of the prior periods presented in the financial statements, ASC 250-10-45-6 requires the following steps to adopt the new accounting principle:

- Adjust the carrying amounts of the assets and liabilities for the cumulative effect of applying the new accounting principle at the beginning of the earliest period presented for which it is practicable to make the computation.

- Any offsetting adjustment required by applying Step 1 is made to beginning retained earnings (or other applicable components of equity or net assets) of that period.

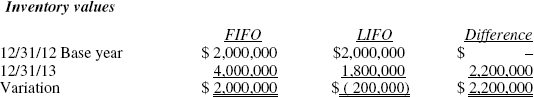

Inability to determine effects on any prior periods. If it is impracticable to determine the cumulative effect of adoption of the new accounting principle on any prior periods, ASC 250-10-45-7 requires that the new principle be applied prospectively as of the earliest date that it is practicable to do so. The most common example of this occurs when management of a reporting entity decides to change its inventory costing assumption from first-in, first-out (FIFO) to last-in, first-out (LIFO), as illustrated in the following example:

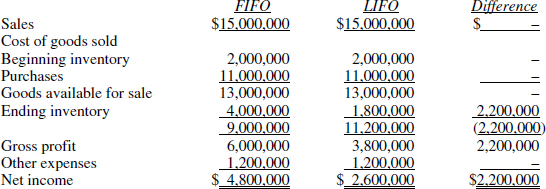

During 2013 Warady Inc. decided to change the method used for pricing its inventories from FIFO to LIFO. The inventory values are as listed below using both FIFO and LIFO methods. Sales for the year were $15,000,000 and the company's total purchases were $11,000,000. Other expenses were $1,200,000 for the year. The company had 1,000,000 shares of common stock outstanding throughout the year.

The computations for 3 would be as follows:

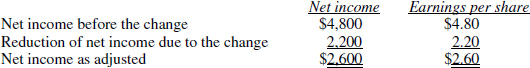

The following is an example of the required disclosure in this circumstance:

During 2013, management changed the company's method of accounting for all of its inventories from first-in, first-out (FIFO) to last-in, first-out (LIFO). The change was made because management believes that the LIFO method provides a better matching of costs and revenues. In addition, with the adoption of LIFO, the company's inventory pricing method is consistent with the method predominant in the industry. The change and its effect on net income ($000 omitted except for per share amounts) and earnings per share for 2013 are as follows:

Management has not retrospectively applied this change to prior years' financial statements because beginning inventory on January 1, 2013, using LIFO is the same as the amount reported on a FIFO basis at December 31, 2012. As a result of this change, the current period's financial statements are not comparable with those of any prior periods. The FIFO cost of inventories exceeds the carrying amount valued using LIFO by $2,200,000 at December 31, 2013.

Disclosure of Prospective Changes in GAAP

Disclosing the impact of newly established GAAP that has not yet become effective.

The accounting principles used in the reporting entity's financial statements may comply with GAAP as of the reporting date, but those principles may become unacceptable at a specified future date due to the issuance of a new accounting standard that is not yet effective. If the new GAAP, when adopted, is expected to materially affect the future financial statements, it is necessary to inform the users of the current financial statements about the future change. The objective of such a disclosure is to ensure that the financial statements are not misleading and that the users are provided adequate information to assess the significance of adopting the new GAAP on the reporting entity's future financial statements.

In some cases, the effect of the future change will be so pervasive as to necessitate the presentation of pro forma financial data to supplement the historical financial statements. The pro forma data would present the effects of the future adoption as if it had occurred at the date of the statement of financial position. The pro forma data may be presented in a column next to the historical data, in the notes to the financial statements, or separately accompanying the basic historical financial statements. Disclosure may also be needed of other future effects that may be triggered by the adoption of the new GAAP, such as adverse effects on the reporting entity's compliance with its debt covenants.

The best source of guidance in determining the form and content of these disclosures is ASC 250-10-S99. While this guidance is applicable to public companies, it also can be interpreted to apply to nonpublic companies as “practices that are widely recognized and prevalent.” Under this requirement management is to disclose:

- A brief description of the new standard.

- The date the reporting entity is required to adopt the new standard.

- If the new standard permits early adoption and the reporting entity plans to do so, the date that the planned adoption will occur.

- The method of adoption that management expects to use. If this determination has not yet been made, then a description of the alternative methods of adoption that are permitted by the new standard.

- The impact that the new standard will have on reported financial position and results of operations. If management has quantified the impact, then it is to disclose the estimated amount. If management has not yet determined the impact or if the impact is not expected to be material, this is to be disclosed.

The SEC staff also encourages the following additional disclosures:

- The potential impact of adoption on such matters as loan covenant compliance, planned or intended changes in business practices, changes in availability of or cost of capital, and the like.

- Newly issued standards that are not expected to materially affect the reporting entity should nevertheless be disclosed with an accompanying statement that adoption is not expected to have a material effect on the reporting entity.

- When the newly issued standard only affects disclosure and the future disclosures are expected to be significantly different from the current disclosures, it is desirable to provide the reader with details.

Proposed GAAP.

There is no requirement under GAAP or under SEC rules to disclose the potential effects of standards that have been proposed but not yet issued. If management wishes to voluntarily disclose information that it believes will provide the financial statement users with useful, meaningful information, the SEC provides guidance (§501.11 of the Codification of Financial Reporting Policies) on how to present this information, either in narrative form or as pro forma information, in a manner that “is reasonable, balanced and not misleading.” In its guidance, the SEC notes that it may be reasonable to cover only those proposals where, based on the standard setter's published agenda, adoption appears imminent. When management chooses to make these disclosures, the disclosures should:

- Provide a brief description of the proposed standard.

- Explain the purpose of the disclosures, the basis of presentation, and any significant assumptions made in preparing them.

- Discuss, in a balanced manner:

- The positive and negative effects of applying the proposed standard,

- The effects the proposed standard would have had on prior results of operations,

- The potential effects of the proposed standard on future periods,

- The effects that can be quantified, and

- The effects, if any, that cannot be quantified.

- Address the entire proposed standard, not just certain aspects of it.

- Limit any disclosures that quantify the effects of the proposed standard to covering only the most recent fiscal year.

- Warn the readers that the final standard, when and if issued, could differ from the proposal that was used as a basis for these disclosures and that, as a result, the actual application of any final standard could result in effects different than those disclosed.

- If necessary for a fair and balanced presentation, provide information regarding more than one proposed standard. There is a risk to the reporting entity that the disclosure may appear to be incomplete or misleading if it discusses the effects of one significant proposed standard but not another.

Reclassifications

Occasionally, a company will choose to change the way it applies an accounting principle, resulting in a change in the way that a particular financial statement caption is displayed or in the individual general ledger accounts that comprise a caption. These reclassifications may occur for a variety of reasons, including:

- In management's judgment, the revised methodology more accurately reflects the economics of a type or class of transaction.

- An amount that was immaterial in previous periods and combined with another number has become material and warrants presentation as a separately captioned line item.

- Due to changes in the business or the manner in which the financial statements are used to make decisions, management deems a different form of presentation to be more useful or informative.

To maintain comparability of financial statements when such changes are made, the financial statements of all periods presented must be reclassified to conform to the new presentation.

Such reclassifications, which usually affect only the statement of income, do not affect reported net income or retained earnings for any period since they result in simply recasting amounts that were previously reported. Normally a reclassification will result in an increase in one or more reported numbers with a corresponding decrease in one or more other numbers. In addition, these changes reflect changes in the application of accounting principles either for which there are multiple alternative treatments, or for which GAAP is silent and thus management has discretion in presentation.

Reclassifications are not explicitly dealt with in GAAP but nevertheless do commonly occur in practice. The following examples are adapted from actual notes that appeared in the summary of significant accounting policies of publicly held companies:

Effective January 1, 2013, the company removed the impact of intellectual property income, gains and losses on sales and other-than-temporary declines in market value of certain investments, realized gains and losses on certain real estate activity, and foreign currency transaction gains and losses from the caption “Selling, General and Administrative Expenses” in the Consolidated Statement of Income. Custom development income was also removed from the “Research, Development, and Engineering” caption on the Consolidated Statement of Income. Intellectual property and custom development income are now presented in a separate caption in the Consolidated Statement of Income. The other items listed above are now included as part of “Other Income and Expense.” Results of prior periods have been reclassified to conform to the current year presentation.

Effective January 1, 2013, management has elected to reclassify certain expenses in its consolidated statements of income. Costs of the order entry function and certain accounting and information technology services have been reclassified from cost of sales to selling, general, and administrative expense. Costs related to order fulfillment have been reclassified from selling, general, and administrative expense to cost of sales. These reclassifications resulted in a decrease to cost of sales and an increase to selling, general, and administrative expense of $31.8 million, and $36.2 million for the years ended December 31, 2012 and 2011, respectively.

Change in Accounting Estimate

The preparation of financial statements requires frequent use of estimates for such items as asset service lives, salvage values, lease residuals, asset impairments, collectability of accounts receivable, warranty costs, pension costs, and the like. Future conditions and events that affect these estimates cannot be estimated with certainty. Therefore, changes in estimates will be inevitable as new information and more experience is obtained. ASC 250-10-45-17 requires that changes in estimates be recognized currently and prospectively. The effect of the change in accounting estimate is accounted for in “(a) the period of change if the change affects that period only or (b) the period of change and future periods if the change affects both.” The reporting entity is precluded from retrospective application, restatement of prior periods, or presentation of pro forma amounts as a result of a change in accounting estimate. See the Technical Alert at the beginning of this chapter for a clarification of a scope exception related to disclosures.

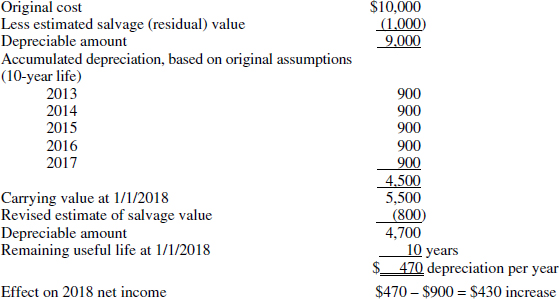

On January 1, 2013, a machine purchased for $10,000 was originally estimated to have a ten-year useful life and a salvage value of $1,000. On January 1, 2017 (five years later), the asset is expected to last another ten years and have a salvage value of $800. As a result, both the current period (the year ending December 31, 2013) and subsequent periods are affected by the change. Annual depreciation expense over the estimated remaining useful life is computed as follows:

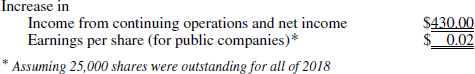

During 2018, management assessed its estimates of the useful lives and residual values of the Company's machinery and equipment. Management revised its original estimates and currently estimates that its production equipment acquired in 2013 and originally estimated to have a 10-year useful life and a residual value of $1,000 will have a 15-year useful life and a residual value of $800. The effects of reflecting this change in accounting estimate on the 2018 financial statements are as follows:

The industry in which ABC Company operates suffers a significant downturn, resulting in a decline in the financial condition of its customers and a noticeable worsening of the days required to collect its accounts receivable. ABC had formerly provided an amount equal to 2% of its credit sales as an increment to the bad debt allowance, resulting in a current balance in the allowance of $105,000. However, the new economic conditions mandate an immediate change to a 4% allowance. Accordingly, ABC provides an additional $105,000 in the current period to increase the previously recorded allowance to meet the new 4% estimate, and also begins providing 4% in the bad debt allowance on all new credit sales. Both of these adjustments are reflected in current period expense, even though the increased allowance on existing receivables pertains to sales made (in part) in a prior reporting period, because the change in estimate was made in the current period based on new circumstances that arose in that period—specifically, the declining credit standing of its customers.

Accounting for long-term construction contracts under the percentage-of-completion method necessarily involves ongoing revisions to estimates of total contract revenue, total contract cost, and extent of progress toward project completion. These revisions represent changes in accounting estimate and, in accordance with ASC 605-35, the change in estimate is accounted for using the cumulative catch-up method. This is applied by

- Computing the percentage of completion, earned revenues, cost of earned revenues, and gross profit on a contract-to-date basis at the date of the statement of financial position using the reporting entity's consistently applied accounting policy for the contract and reflecting the revised estimates.

- Reflecting in the current period's earned revenue and cost of earned revenue the difference between the newly computed contract-to-date results computed in item 1 and those amounts recognized in previous periods.

This approach results in the effect of the change in accounting estimate being reflected in the current period statement of income, and prospectively accounting for the contract using the revised assumptions.

Note that an impairment of a long-lived asset, as described by ASC 360-10-35, is not a change in accounting estimate. Rather, it is an event that is to be treated as an operating expense of the period in which it is recognized, in effect as additional depreciation. (See further discussion in chapter in this volume on ASC 360.)

Change in Accounting Estimate Effected by a Change in Accounting Principle

To change certain accounting estimates, management must adopt a new accounting principle or change the method it uses to apply an accounting principle. In contemplating such a change, management would not be able to separately determine the effects of changing the accounting principle from the effects of changing its estimate. The change in estimate is accomplished by changing the method.

Under ASC 250-10-45-18, a change in accounting estimate that is effected by a change in accounting principle is accounted for in the same manner as a change in accounting estimate, that is, prospectively in the current and future periods affected. However, because management is changing the company's accounting principle or method of applying it, the new accounting principle, as previously discussed, must be preferable to the accounting principle being superseded.

Management may decide, for example, to change its depreciation method for certain types of assets from straight-line to an accelerated method, such as double-declining balance to recognize the fact that those assets are more productive in their earlier years of service because they require less downtime and do not require repairs as frequently. Such a change is permitted by ASC 250-10-45-19 only if management justifies it based on the fact that using the new method is preferable to the old one, in this case because it more accurately matches the costs of production to periods in which the units are produced.

A distinction is made in ASC 250-10-45-20, however, for entities that elect to apply a depreciation method that results in accelerated depreciation until the point during the useful life of the depreciable asset when it is useful to change to straight-line depreciation in order to fully depreciate the asset over the remaining term. At this point, the remaining carrying value (net book value) is depreciated using the straight-line method over its remaining useful life. ASC 250 provides that, if this method is consistently followed by the reporting entity, the changeover to straight-line depreciation is not considered to be an accounting change.

Change in Reporting Entity

An accounting change resulting in financial statements that are, in effect, of a different reporting entity than previously reported on, is retrospectively applied to the financial statements of all prior periods presented in order to show financial information for the new reporting entity for all periods (ASC 250-10-45-21). The change is also retrospectively applied to previously issued interim financial information.

The following qualify as changes in reporting entity:

- Consolidated or combined financial statements in place of individual entities' statements

- A change in the members of the group of subsidiaries that comprise the consolidated financial statements

- A change in the companies included in combined financial statements.

Specifically excluded from qualifying as a change in reporting entity are:

- A business combination accounted for by the purchase method and

- Consolidation of a variable interest entity under ASC 810.

Error Corrections

Errors are sometimes discovered after financial statements have been issued. Errors result from mathematical mistakes, mistakes in the application of GAAP, or the oversight or misuse of facts known or available to the accountant at the time the financial statements were prepared. Errors can occur in recognition, measurement, presentation, or disclosure. A change from an unacceptable (or incorrect) accounting principle to a correct principle is also considered a correction of an error and not a change in accounting principle. Such a change should not be confused with the preferability determination discussed earlier that involves two or more acceptable principles. An error correction pertains to the recognition that a previously used method was not an acceptable method at the time it was employed.

The essential distinction between a change in estimate and the correction of an error depends upon the availability of information. An estimate requires revision because by its nature it is based upon incomplete information. Later data will either confirm or contradict the estimate and any contradiction will require revision of the estimate. An error results from the misuse of existing information available at the time which is discovered at a later date. However, this discovery is not as a result of additional information or subsequent developments.

ASC 250 specifies that, when correcting an error in prior period financial statements, the term “restatement” is to be used. That term is exclusively reserved for this purpose so as to effectively communicate to users of the financial statements the reason for a particular change in previously issued financial statements.

Restatement consists of the following steps:

Step 1 Adjust the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities at the beginning of the first period presented in the financial statements for the cumulative effect of correcting the error on periods prior to those presented in the financial statements.

Step 2 Offset the effect of the adjustment in Step 1 (if any) by adjusting the opening balance of retained earnings (or other components of equity or net assets, as applicable to the reporting entity) for that period.

Step 3 Adjust the financial statements of each individual prior period presented for the effects of correcting the error on that specific period (referred to as the period-specific effects of the error).

Assume that Truesdell Company had overstated its depreciation expense by $50,000 in 2010 and $40,000 in 2012, both due to mathematical mistakes. The errors affected both the financial statements and the income tax returns in 2011 and 2012 and are discovered in 2013.

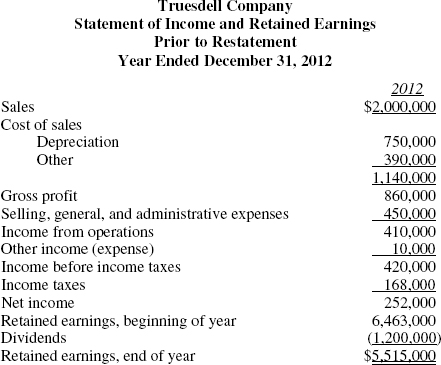

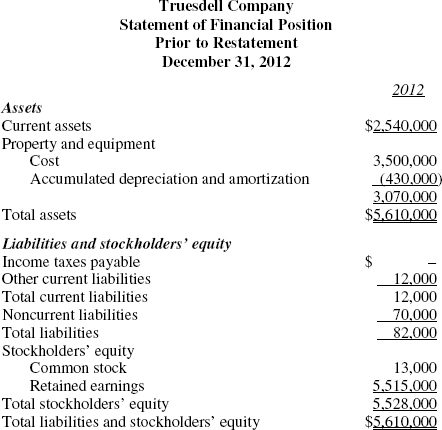

Truesdell's statements of financial position and statements of income and retained earnings as of and for the year ended December 31, 2012, prior to the restatement were as follows:

The following steps are followed to restate Truesdell's prior period financial statements:

Step 1 Adjust the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities at the beginning of the first period presented in the financial statements for the cumulative effect of correcting the error on periods prior to those presented in the financial statements.

The first period presented in the financial statements is 2012. At the beginning of that year, $50,000 of the mistakes had been made and reflected on both the income tax return and financial statements. Assuming a flat 40% income tax rate and ignoring the effects of penalties and interest that would be assessed on the amended income tax returns, the following adjustment would be made to assets and liabilities at January 1, 2012:

![]()

Step 2 Offset the effect of the adjustment in Step 1 by adjusting the opening balance of retained earnings (or other components of equity or net assets, as applicable to the reporting entity) for that period.

Retained earnings at the beginning of 2012 will increase by $30,000 as the offsetting entry resulting from Step 1.

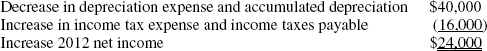

Step 3 Adjust the financial statements of each individual prior period presented for the effects of correcting the error on that specific period (referred to as the period-specific effects of the error).

The 2012 prior period financial statements will be corrected for the period-specific effects of the restatement as follows:

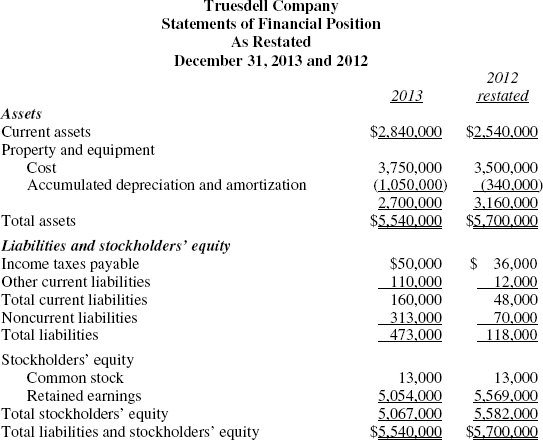

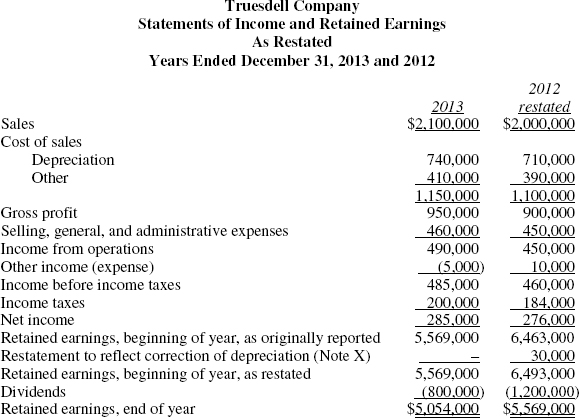

The restated financial statements are presented below.

When restating previously issued financial statements, management is to disclose

- The fact that the financial statements have been restated

- The nature of the error

- The effect of the restatement on each line item in the financial statements

- The cumulative effect of the restatement on retained earnings (or other applicable components of equity or net assets)

- At the beginning of the earliest period presented in comparative financial statements, or

- At the beginning of the period in single-period financial statements

- The effect on net income, both gross and net of income taxes

- For each prior period presented in comparative financial statements or

- For the period immediately preceding the period presented in single-period financial statements

- For public companies (or others electing to report earnings per share data), the effect of the restatement on affected per-share amounts for each prior period presented.

These disclosures need not be repeated in subsequent periods.

The correction of an error in the financial statements of a prior period discovered subsequent to their issuance is reported as a prior period adjustment in the financial statements of the subsequent period.

Evaluating Uncorrected Misstatements

Misstatements, particularly if detected after the financial statements have been produced and distributed, may under certain circumstances be left uncorrected. This decision is directly impacted by judgments about materiality, an important concept discussed in Chapter 1. The financial statement preparer is expected to exercise professional judgment in determining the level of materiality to apply in order to cost-effectively prepare full, complete, and accurate financial statements in a timely manner. However, there have been instances where the materiality concept has been used to rationalize the noncorrection of errors that should have been dealt with, and indeed even to excuse errors known when first committed. The fact that the concept of materiality has sometimes been abused led to the promulgation of further guidance relative to error corrections.

Although independent auditors are charged with obtaining sufficient evidence to enable them to provide the financial statement user with reasonable assurance that management's financial statements are free of material misstatement, the financial statements are primarily the responsibility of the preparers. Certain auditing literature is therefore germane to the preparers' consideration of matters such as error corrections and application of materiality guidelines. These matters are further explored in the following paragraphs.

Types of misstatements.

Preparers of financial statements need to have control procedures to reduce the risk of accounting errors being committed and not detected. From the auditors' perspective, it is required that the examination be conducted in a manner that will provide reasonable assurance of detecting material misstatements, including those resulting from errors. Known misstatements arise from:

- Incorrect selection or application of accounting principles

- Errors in gathering, processing, summarizing, interpreting, or overlooking relevant data

- An intent to mislead the financial statement user to influence their decisions

- To conceal theft.

Likely misstatements arise from

- Differences in judgment between management and the auditor regarding accounting estimates where the amount presented in the financial statements is outside the range of what the auditor believes is reasonable

- Amounts that the auditor has projected based on the results of performing statistical or nonstatistical sampling procedures on a population.

Management, in assessing the impact of uncorrected misstatements, is required to assess materiality both quantitatively and qualitatively from the standpoint of whether a financial statement user would be misled if a misstatement were not corrected or if, in the case of informative disclosure errors, full disclosure was not made. Qualitative considerations include (but are not limited to) whether the misstatement

- Arose from estimates or from items capable of precise measurement and, if the misstatement arose from an estimate, the degree of precision inherent in the estimation process

- Masks a change in earnings or other trends

- Hides a failure to meet analysts' consensus expectations for the reporting entity

- Changes a loss to income or vice versa

- Concerns a segment or other portion of the reporting entity's business that has been identified as playing a significant role in operations or profitability

- Affects compliance with loan covenants or other contractual commitments

- Increases management's compensation by affecting a performance measure used as a basis for computing it

- Involves concealment of an unlawful transaction.

Misstatements from prior years.

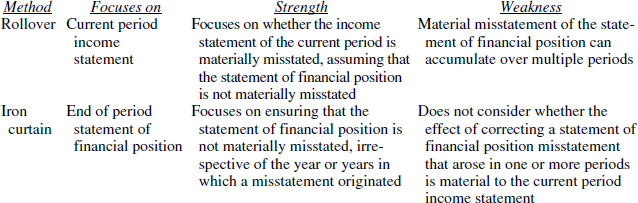

Management may have decided to not correct misstatements that occurred in one or more prior years because, in their judgment at the time, the financial statements were not materially misstated. Two methods of making that materiality assessment—sometimes referred to as the “rollover” and the “iron curtain” methods—have been widely used in practice. These are described and illustrated in the following paragraphs.

The rollover method quantifies a misstatement as its originating or reversing effect on the current period's statement of income, irrespective of the potential effect on the statement of financial position of one or more prior periods' accumulated uncorrected misstatements.

The iron curtain method, on the other hand, quantifies a misstatement based on the accumulated uncorrected amount included in the current, end-of-period statement of financial position, irrespective of the year (or years) in which the misstatement originated.

Each of these methods, when considered separately, has strengths and weaknesses, as follows:

Guidance for SEC registrants.

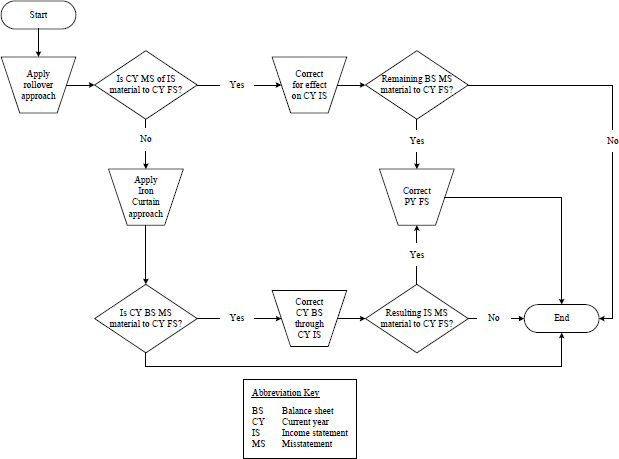

The SEC staff issued, Staff Accounting Bulletin (SAB) 108, Considering the Effects of Prior Year Misstatements in Current Year Financial Statements, to address how registrants (i.e., publicly held corporation) are to evaluate misstatements. SAB 108 prescribes that if a misstatement is material to either the income statement or the statement of financial position, it is to be corrected in a manner set forth in the bulletin and illustrated in the example and diagram below.

Lenny Payne, the CFO of Flamingo Industries, is preparing the company's 2013 financial statements. The company has consistently overstated its accrued liabilities by following a policy of accruing the entire audit fee it will pay its independent auditors for auditing the financial statements for the reporting year, even though approximately 80% of the work is performed in, and is thus an expense of, the following year.

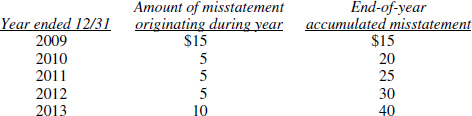

Due to regular increases in audit fees, the overstatement of liabilities at 12/31/2013 has accumulated as follows:

Lenny has consistently used the rollover approach to assess materiality and, in all previous years, had judged the amount of the misstatement that originated during that year to be immaterial. The guidance in SAB 108 is illustrated in the following decision diagram:

Following the decision tree, Lenny analyzes the misstatement as follows:

- Applying the rollover approach, as he had done consistently in the past, Lenny computes the misstatement as the $10 that originated in 2013. In his judgment, this amount is immaterial to the 2013 income statement.

- Applying the iron curtain approach, Lenny evaluates whether the accumulated misstatement of $40 materially misstates the statement of financial position at 12/31/2013. Lenny believes that, considering both quantitative and qualitative factors, the misstatement has grown to the point where it does result in a materially misstated statement of financial position.

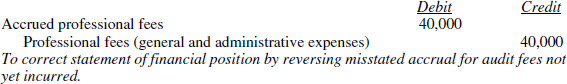

According to SAB 108 and as shown on the diagram, Lenny would record an adjustment to correct the statement of financial position as follows:

Upon review of the effect of the correcting entry, Lenny believes that recording the entry will result in a material misstatement to the 2013 income statement. Consequently, to avoid this result, the prior years' financial statements of Flamingo Industries would, under normal circumstances, be required to be restated as previously discussed in the section of this chapter titled “Error Corrections.” This would be the case even if the adjustment to the prior year financial statements was, and continues to be, immaterial to those financial statements. The SEC would not, however, require Flamingo Industries to amend previously filed reports; instead, registrants are permitted to make the correction in the next filing submitted to the SEC that includes the prior year financial statements.

If the cumulative effect adjustment occurs in an interim period other than the first interim period, the SEC waived the requirement that previously filed interim reports for that fiscal year be amended. Instead, comparative information presented for interim periods of the first year subsequent to initial application are to be adjusted to reflect the cumulative effect adjustment as of the beginning of the fiscal year of initial application. The adjusted results are also required to be included in the disclosures of selected quarterly information that are required by Regulation S-K, Item 302.

Entities that do not meet the criteria to use the cumulative effect adjustment are required to follow the provisions of ASC 250 that require restatement of all prior periods presented in the filing.

Interim Reporting Considerations

If a change in accounting principle is made in an interim period, the change is made using the same methodology for retrospective application discussed and illustrated earlier in this chapter. Management is precluded from using the impracticability exception to avoid retrospective application to prechange interim periods of the same fiscal year in which the change is made. Thus, if it is impracticable to apply the change to those prechange interim periods, the change can only be made as of the beginning of the following fiscal year. FASB believes this situation will rarely occur in practice.

ASC 270 requires that interim financial reports disclose any changes in accounting principles or the methods of applying them from those that were employed in:

- The prior fiscal year;

- The comparable interim period of the prior fiscal year; and

- The preceding interim periods of the current fiscal year.

The disclosures required by ASC 250 for changes in accounting principle are to be made, in full, in the financial statements of the interim period in which the change is made.

Public companies.

When a public company adopts a new standard in an interim period, the ASC 270 disclosures cited above are to be supplemented, as applicable, with all disclosures required by the newly adopted standard to be included in annual financial statements. If the change is made in a period other than the first quarter, prior filings are not required to be amended; however, adjustment of each prior quarter's results is to be included in the filing for the quarter in which the new principle is being adopted. If the newly adopted standard requires retrospective application to all prior periods, the prior interim quarters are also to be presented on an adjusted basis.

In addition, a special disclosure rule applies to a public company that

- Changes accounting principles in the fourth quarter of a fiscal year;

- Regularly reports interim financial information; and

- Does not separately disclose in its annual report (or in a separate report) the minimum summarized information required by ASC 270 for the fourth quarter of the fiscal year.

When all three of these conditions are present, management is required to disclose in a note to the annual financial statements the effects of the change on interim period results.

Going concern considerations.

Financial statements prepared in accordance with GAAP presume that the reporting entity is expected to remain in operation for the foreseeable future. This “going concern” assumption is important, since in its absence many accounting conventions and practices (e.g., depreciation of long-lived assets over expected economic lives) would not be sensible, as the ability to realize the economic benefits of such assets would be in doubt.

US auditing standards have long required auditors to affirmatively evaluate whether there was substantial doubt about the ability of the reporting entity to continue as a going concern for a reasonable period following the date of the financial statements, but not for longer than one year from that date. When substantial doubt was found to exist, this was cited in the auditors' report, and the financial statements were required to include, as footnote disclosure, information about the reasons for such doubts, as well as about management's plans to cope with the circumstances. (When such informative disclosures were not provided by management, the auditors were generally required to qualify their opinions due to lack of adequate disclosure, notwithstanding inclusion of “going concern” language in the auditors' report itself.)

Disclosures about events subsequent to the date of the statement of financial position.

ASC 855-10, Subsequent Events, also brings into the accounting literature a topic previously addressed by US auditing standards. The objective of this pronouncement is to establish general standards of accounting for, and disclosure of, events that occur subsequent to the balance sheet date but before financial statements are issued or are available to be issued.

In particular, the standard sets forth:

- The period after the balance sheet date during which management of a reporting entity would evaluate events or transactions that may occur for potential recognition or disclosure in the financial statements;

- The circumstances under which an entity would recognize events or transactions occurring after the balance sheet date in its financial statements; and

- The disclosures that an entity would make about events or transactions that occurred after the balance sheet date.

ASC 855-10 does not result in significant changes in the subsequent events that an entity reports—either through recognition or disclosure—in its financial statements. However, it does introduce a new concept—that of financial statements being available to be issued. The standard requires disclosure of the date through which the reporting entity has evaluated subsequent events, as well as the basis for that date, which may be that it is the date when the financial statements were issued, or when the financial statements were available to be issued. This disclosure is intended to alert the users of financial statements that an entity has not evaluated events subsequent to that date in the set of financial statements being presented.

As has been previously defined under US auditing standards, two types of subsequent events are defined by ASC 855-10. These are

- Events or transactions that provide additional evidence about conditions that existed at the date of the balance sheet, including the estimates inherent in the process of preparing financial statements (“recognized subsequent events”).

- Events that provide evidence about conditions that did not exist at the date of the balance sheet, but arose subsequent to that date (“nonrecognized subsequent events”).

The standard defines two key terms pertaining to the issuance, and the availability for issuance, of the financial statements, as these represent the alternative acceptable cut-off dates for the recognition or disclosure of subsequent events. Regarding the former, financial statements are considered issued when they are widely distributed to shareholders and other financial statement users for general use and reliance in a form and format that complies with GAAP. Financial statements are available to be issued when they are complete in a form and format that complies with GAAP and all approvals necessary for issuance have been obtained, for example, from management, the board of directors, or significant shareholders.

An entity that has a historical practice or current expectation of widely distributing its financial statements to its shareholders and other financial statement users (including, but not limited to publicly held companies) will be required to evaluate subsequent events through the date that the financial statements are actually issued. For all other entities, the evaluation of subsequent events must be through the date that the financial statements are available to be issued.

Consistent with current practice, ASC 855-10 requires that reporting entities recognize in their financial statements the effects of all subsequent events that provide additional evidence about conditions that existed at the date of the balance sheet, including the estimates inherent in the process of preparing financial statements.

The standard provides two examples of recognized subsequent events. The first relates to events giving rise to litigation that took place before the balance sheet date, but where that litigation is settled after the balance sheet date for an amount different from whatever liability was recorded in the accounts. In such an instance, the settlement amount should be recognized in the financial statements, since the subsequent event confirms the obligation that existed at the date of the statement of financial position.

The other example describes subsequent events affecting the realization of assets, such as receivables and inventories or the settlement of estimated liabilities, when those events represent the culmination of conditions that had existed over a relatively long period of time. Here, too, the asset or liability is to be reported in the period-end statement of financial position. It states that a loss on an uncollectible trade account receivable that occurs as a result of a customer's deteriorating financial condition leading to bankruptcy after the balance sheet date would ordinarily be indicative of conditions existing at the balance sheet date, and accordingly would call for recognition of the effects of the customer's bankruptcy filing in the financial statements before they are issued or are available to be issued.

On the other hand, there are subsequent events that should not be given formal recognition in the financial statements, as they only provide evidence about conditions that arose after the date of the statement of financial position, and did not exist at that date. The standard provides the following examples of such unrecognized subsequent events:

- Sale of a bond or capital stock issued after the balance sheet date

- A business combination that occurs after the balance sheet date

- Settlement of litigation when the event forming the basis for the claim took place after the balance sheet date

- Loss of plant or inventories as a result of fire or natural disaster that occurred after the balance sheet date

- Losses on receivables resulting from conditions (such as a customer's major casualty) arising after the balance sheet date

- Changes in the quoted market prices of securities or foreign exchange rates after the balance sheet date

- Entering into significant commitments or contingent liabilities, for example, by issuing significant guarantees after the balance sheet date.

ASC 855-10 provides for several disclosures. The reporting entity must disclose the date through which subsequent events have been evaluated, as well as whether that date is the date the financial statements were issued or the date the financial statements were available to be issued.

For nonrecognized subsequent events that are of such a nature that they must be disclosed to keep the financial statements from being misleading, disclosure is required of the following:

- The nature of the event; and

- An estimate of its financial effect, or a statement that such an estimate cannot be made.

The reporting entity is also required to consider supplementing the historical financial statements with pro forma financial data, and a nonrecognized subsequent event may be so significant that disclosure can best be made by means of pro forma financial data. In such a circumstance, the pro forma presentation or data is to give effect to the event as if it had occurred on the balance sheet date. In some of these situations, the reporting entity should consider presenting pro forma statements, usually a balance sheet only, in columnar form on the face of the historical statements.

Finally, ASC 855-10 addresses those situations where an entity may occasionally need to reissue financial statements. This may occur in reports filed with the SEC or other regulatory agencies. After the original issuance of the financial statements, events or transactions may have occurred that require disclosure in the reissued financial statements to keep them from being misleading. The standard provides that the entity is not to recognize events occurring between the time of original issuance and reissuance of the financial statements unless the adjustment is required by GAAP or regulatory requirements. Of course, the entity does have to make adjustments to the financial statements for the correction of an error, which are distinct from subsequent events as that term is used in this standard.

The reporting entity may consider presenting pro forma financial statements to supplement the historical financial statements in certain circumstances, as noted above. However, it is not to recognize events or transactions occurring subsequent to the original issuance in financial statements that are reissued in comparative form along with financial statements of subsequent periods unless the adjustment meets the criteria for pro forma presentation, above, or unless doing so is otherwise required by GAAP.

Other Sources

| See ASC Location – Wiley GAAP Chapter... | For information on... |

| ASC 260-10-55-15 through 55-16 | The effect of restatements expressed in per-share terms |

| ASC 323-10-45-1 through 45-2. | The classification of an investor's share of error corrections reported in the financial statements of the investee |

1 ASC 250 provides an exception to the requirement for retroactive restatement when it is impracticable to make the restatement. This exception is only permitted to be used under specified conditions.

2 This is generally limited to (a) presentation of consolidated or combined financial statements instead of financial statements of individual entities, (b) a change in the specific subsidiaries making up a group of entities for which consolidated financial statements are presented, and (c) changing the entities included in combined financial statements. Neither a business combination under ASC 805 nor consolidation of a variable interest entity under ASC 810 is considered a change in reporting entity.

3 The word “restatement” is only to be used to describe and/or present corrections of prior period errors.