44 ASC 740 INCOME TAXES

Evolution of Accounting for Income Taxes

Simplified example of interperiod income tax allocation using the liability method

Temporary and Permanent Differences

Temporary differences from share-based compensation arrangements

Temporary differences arising from convertible debt with a beneficial conversion feature

Treatment of Net Operating Loss Carryforwards

Example—Net operating loss carryforwards and income tax credit carryforwards

Measurement of Deferred Income Tax Assets and Liabilities

Scheduling of the reversal years of temporary differences

Determining the appropriate income tax rate

Computing deferred income taxes

Computation of deferred income tax liability and asset—Basic example

The Valuation Allowance for Deferred Income Tax Assets Expected to Be Unrealizable

Establishment of a valuation allowance

Example of applying the more-likely-than-not criterion to a deferred income tax asset

Impact of a qualifying tax strategy

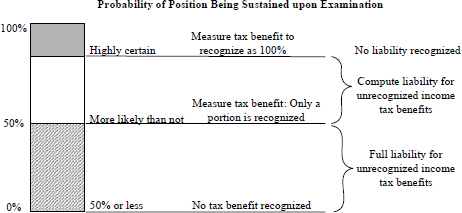

Accounting for Uncertainty in Income Taxes

Initial recognition and measurement

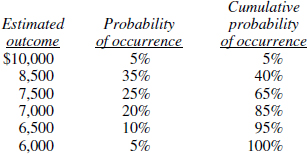

Example of the two-step initial recognition and measurement process

Subsequent recognition, derecognition, and measurement

Applicability to business combinations

The Effect of Tax Law Changes on Previously Recorded Deferred Income Tax Assets and Liabilities

Enactment occurring during an interim period

Changes in a valuation allowance for an acquired entity's deferred income tax asset

Computation of a deferred income tax asset with a change in rates

Reporting the Effect of Tax Status Changes

Reporting the Effect of Accounting Changes for Income Tax Purposes

Example of adjustment for prospective catch-up adjustment due to change in tax accounting

Income Tax Effects of Dividends Paid on Shares Held by Employee Stock Ownership Plans

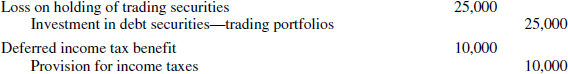

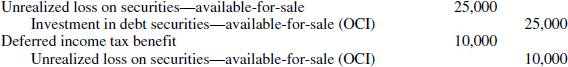

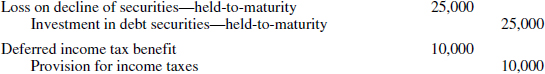

Deferred Income Tax Effects of Changes in the Fair Value of Debt and Marketable Equity Securities

Example of deferred income taxes on investments in debt and marketable equity securities

Other guidance on accounting for investments

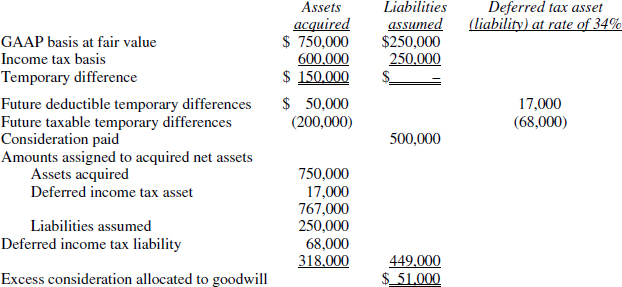

Purchase-method accounting under ASC 805

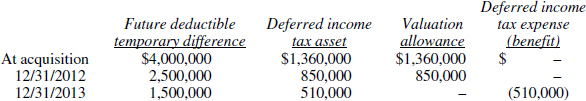

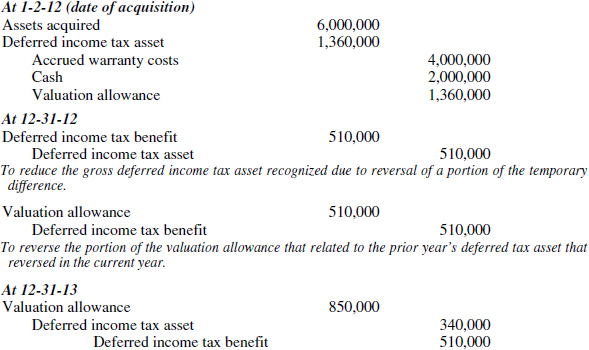

Example of subsequent realization of a deferred income tax asset in a purchase business combination

Acquisition-method accounting under ASC 805 and ASC 810-10-65

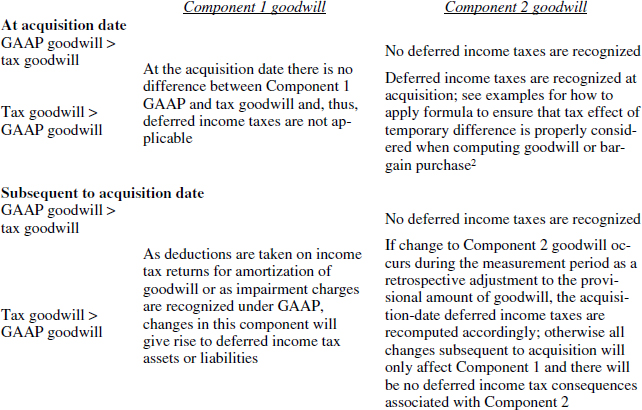

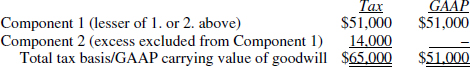

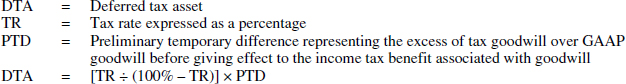

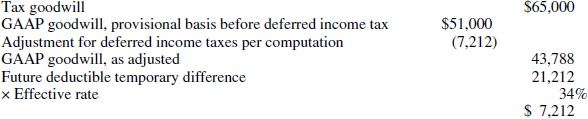

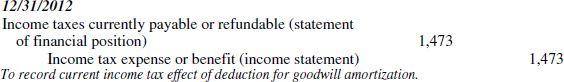

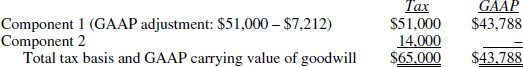

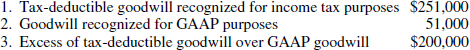

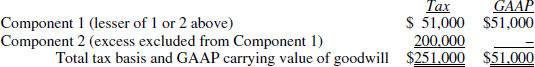

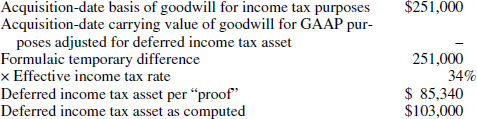

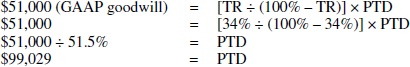

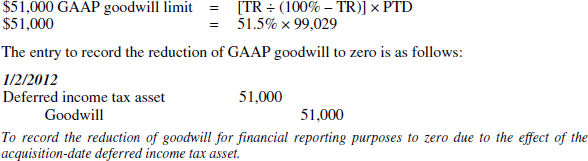

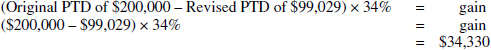

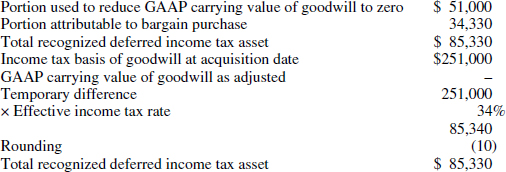

Example of deferred income taxes where tax-deductible goodwill exceeds GAAP goodwill

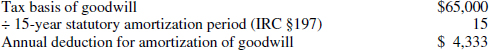

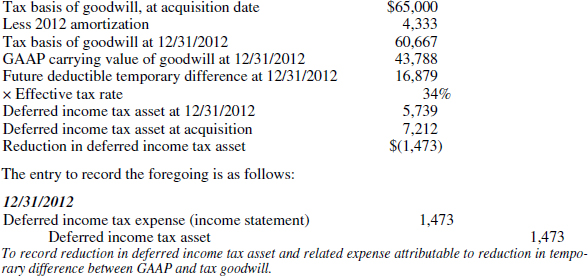

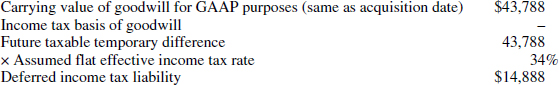

Example of effect of income tax goodwill amortization on deferred income taxes

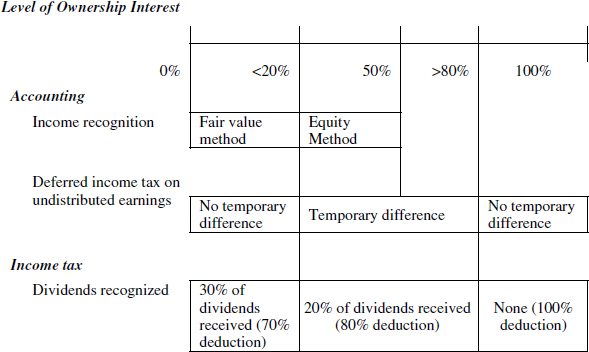

Tax Allocation for Business Investments

Undistributed earnings of a subsidiary

Undistributed earnings of an investee

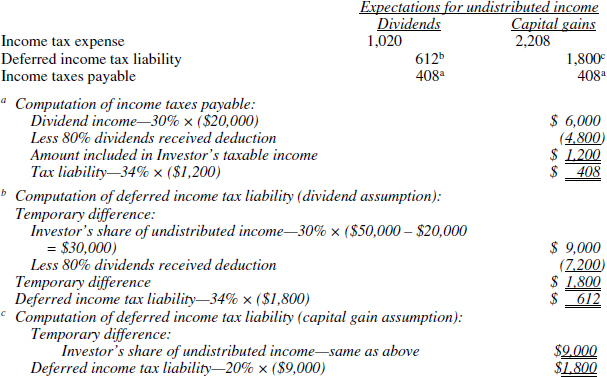

Example of income tax effects from investee company

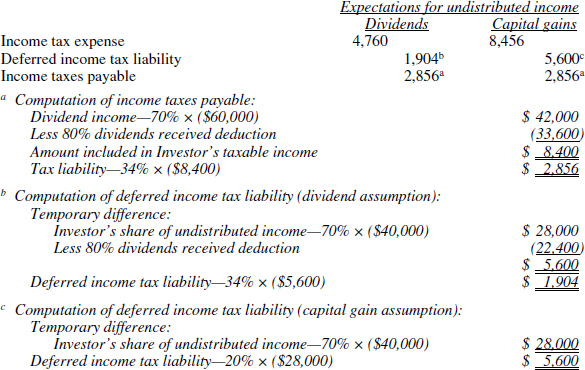

Example of income tax effects from subsidiary

Separate Financial Statements of Subsidiaries or Investees

Tax credits related to dividend payments

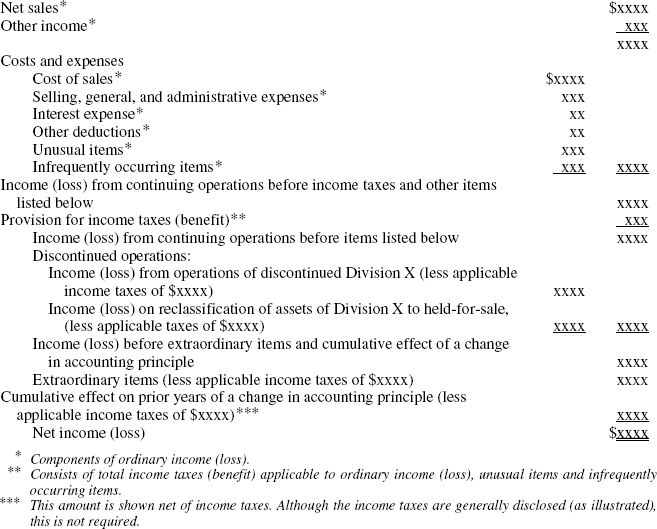

Intraperiod Income Tax Allocation

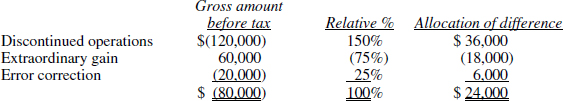

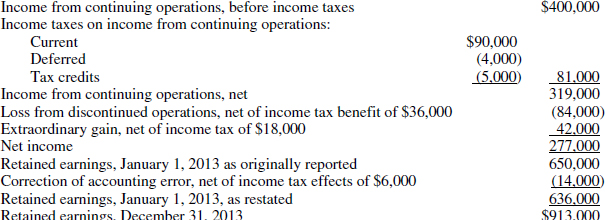

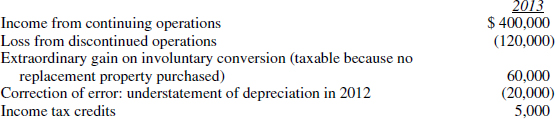

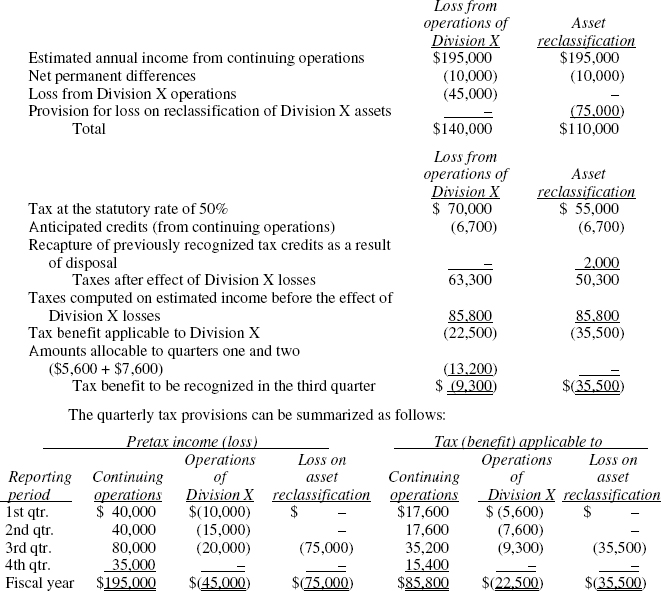

Comprehensive example of the intraperiod income tax allocation process

Classification in the Statement of Financial Position

Accounting for Income Taxes in Interim Periods

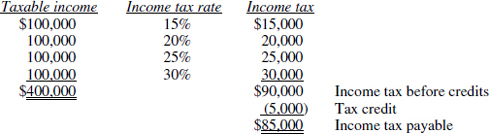

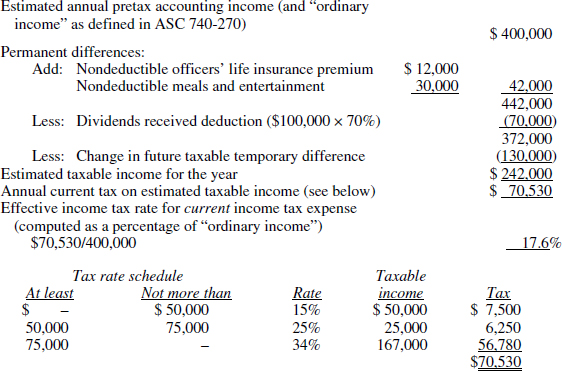

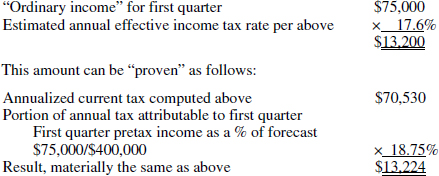

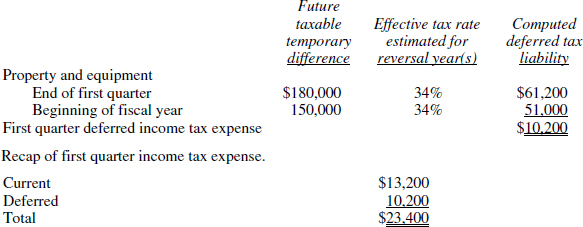

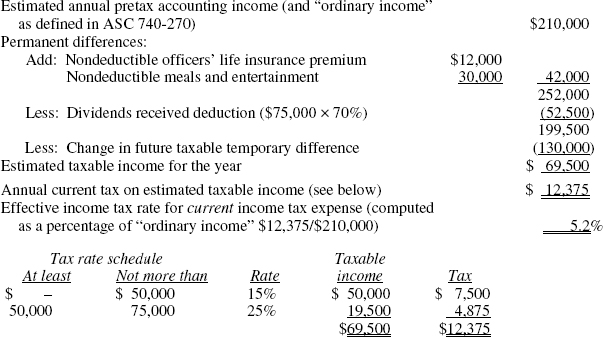

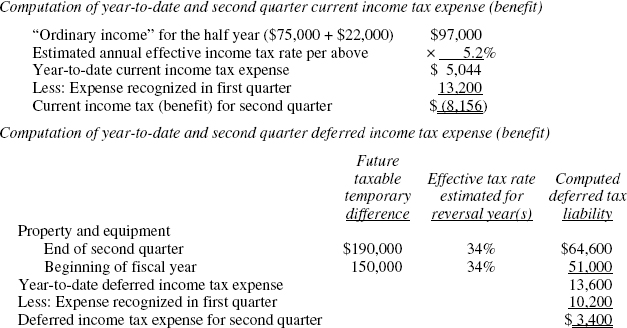

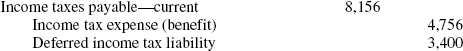

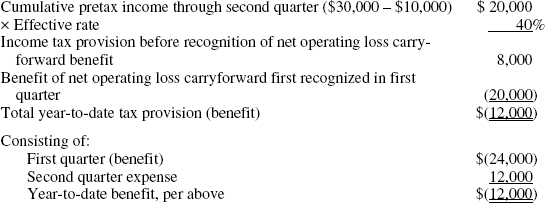

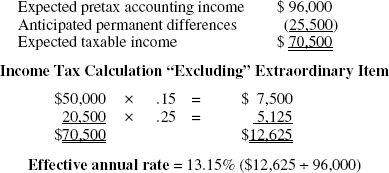

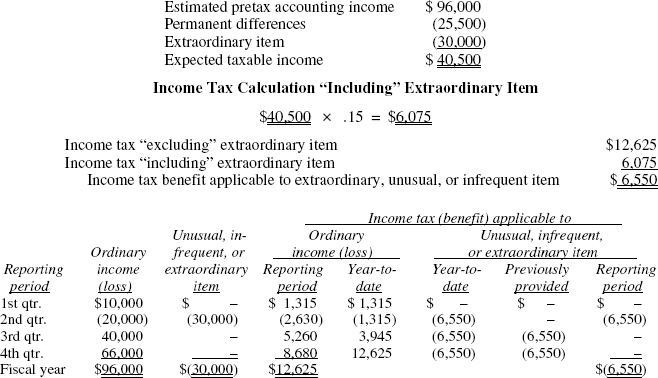

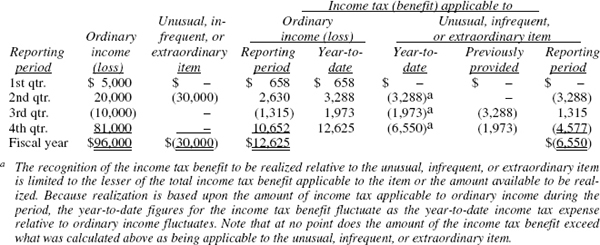

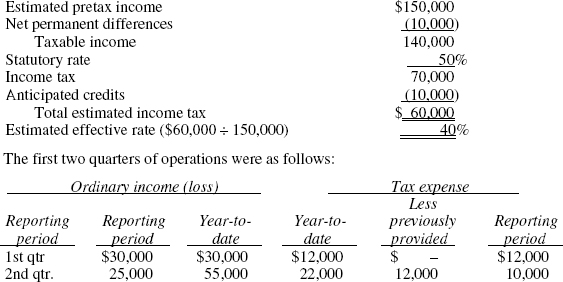

Basic example of interim period accounting for income taxes

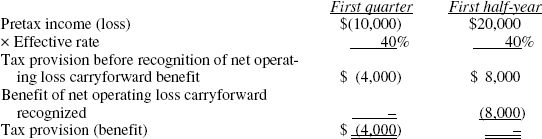

Net operating losses in interim periods

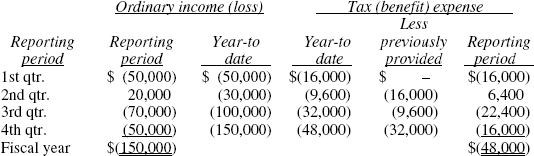

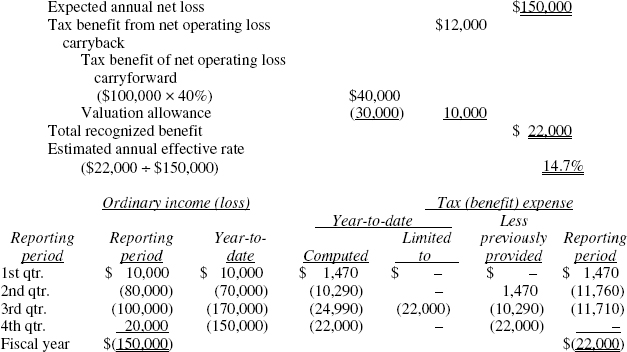

Example of interim-period valuation allowance adjustments due to revised judgment

Example of recognizing net operating loss carryforward benefit as actual liabilities are incurred

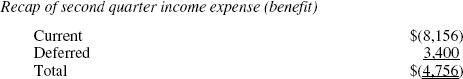

Income tax provision applicable to interim period nonoperating items

PERSPECTIVE AND ISSUES

Subtopics

ASC 740, Income Taxes, consists of three Subtopics:

- ASC 740-10, Overall, which provides most of the guidance on accounting and reporting for income taxes

- ASC 740-20, Intraperiod Tax Allocation, which provides guidance on the process of allocating income tax benefits or expenses to different components of comprehensive income

- ASC 740-30, Other Considerations or Special Areas, which provides guidance for specific limited exceptions related to investments in subsidiaries and corporate joint ventures arising from undistributed earnings or other causes.

Scope and Scope Exceptions

The term “tax position” is used in ASC 740-10 to refer to each judgment that management makes on an income tax return that has been or will be filed that affects the measurement of current or deferred income tax assets and liabilities at the date of each interim or year-end statement of financial position. Tax positions include:

- Deductions claimed

- Deferrals of current income tax to one or more future periods

- Income tax credits applied

- Characterization as capital gain versus ordinary income

- Whether or not to report income on an income tax return

- Whether or not to file an income tax return in a particular jurisdiction.

The effects of a tax position can result in a permanent reduction of income taxes payable or deferral of the payment of income taxes to a future year. The taking of a tax position can also affect management's estimate of the valuation allowance sufficient to reflect its estimate of the amount of deferred income tax assets that are realizable.

ASC 740-10 applies to income taxes accounted for in accordance with ASC 740, and thus does not apply directly or by analogy to other taxes, such as real estate, personal property, sales, excise, or use taxes. The scope of ASC 740-10 includes any entity potentially subject to income taxes, including:

- Nonprofit organizations

- Flow-through entities (e.g., partnerships, limited liability companies, and S corporations)

- Entities whose income tax liabilities are subject to 100% credit for dividends paid such as real estate investment trusts (REITs) and registered investment companies.

Overview

Reporting entities are required to file income tax returns and pay income taxes in the domestic (federal, state, and local) and foreign jurisdictions in which they do business. GAAP require that financial statements be prepared on an accrual basis and that, consequently, the reporting entity is required to accrue a liability for income taxes owed or expected to be owed with respect to income tax returns filed or to be filed for all applicable tax years and in all applicable jurisdictions.

A longstanding debate has involved the controversial recognition of benefits (or reduced obligations) related to income tax positions that are uncertain or aggressive and which, if challenged, have a more-than-slight likelihood of not being sustained, resulting in the need to pay additional income taxes, often with interest and—sometimes—penalties added. Preparers have objected to presenting income tax obligations for such positions, often on the not-unreasonable theory that to do so would provide taxing authorities with a “road map” to the challengeable income tax positions taken by the reporting entity. With the issuance of FIN 48, Accounting for Uncertainty in Income Taxes, uncertain income tax positions were to become subject to formal recognition and measurement criteria, as well as to extended disclosure requirements under GAAP. The guidance is incorporated in ASC 740 and is explained and illustrated in detail in this chapter.

The computation of taxable income for the purpose of filing federal, state, and local income tax returns differs from the computation of net income under GAAP for a variety of reasons. In some instances, referred to as temporary differences, the timing of income or expense recognition varies. In other instances, referred to as permanent differences, income or expense recognized for income tax purposes is never recognized under GAAP, or vice versa. An objective under GAAP is to recognize the income tax effects of transactions in the period that those transactions occur. Consequently, deferred income tax benefits and obligations frequently arise in financial statements.

The basic principle is that the deferred income tax effects of all temporary differences (which are defined in terms of differential bases in assets and liabilities under income tax and GAAP accounting) are to be formally recognized. To the extent that deferred income tax assets are of doubtful realizability—are not “more likely than not to be realized”—a valuation allowance is provided, analogous to the allowance for uncollectible receivables.

The process of interperiod income tax allocation, which gives rise to deferred income tax assets and liabilities, is required under GAAP. As with many accounting measurements, the prescribed methodology has varied depending upon whether the primary objective was accuracy of the statement of financial position or of the income statement.

Under ASC 740, purchase price allocations made pursuant to purchase-method business combinations under ASC 805, Business Combinations (and recognized values pursuant to acquisition-method business combinations under its replacement standard, ASC 805) are made gross of income tax effects, and any associated income tax benefit or obligation is recognized separately.

Postcombination changes in valuation allowances for an acquired entity's deferred income tax assets no longer automatically reduce recorded goodwill and intangibles. The accounting depends upon whether the changes occur during or after the expiration of the measurement period.

If the change occurs during the prescribed measurement period, not to exceed one year from the acquisition date, it is first applied to adjust goodwill until goodwill is eliminated, with any excess adjustment remaining being recorded as a gain from a bargain purchase. If the change occurs subsequent to the measurement period, it is recognized in the period of change as a component of income tax expense or benefit, or, in the case of certain specified exceptions, as a direct adjustment to contributed capital. Notably, the transition provisions of ASC 805 require this treatment to be applied prospectively after the effective date of the standard, even with respect to acquisitions that were originally recorded under the predecessor standard.

The income tax effects of net operating loss or tax credit carryforwards are treated as deferred income tax assets just like any other deferred income tax benefit.

With its statement of financial position orientation, ASC 740 requires that the amounts presented be based on the amounts expected to be realized, or obligations expected to be liquidated. Use of an average effective income tax rate convention is permitted. The effects of all changes in the deferred income tax assets and liabilities flow through the income tax provision in the income statement; consequently, income tax expense is normally not directly calculable based on pretax accounting income in other than the simplest situations.

Discounting of deferred income taxes has never been permitted under GAAP, even though the ultimate realization and liquidation of deferred income tax assets and liabilities is often expected to occur far in the future. The inability to predict accurately the timing of the realization of deferred income tax benefits or the payment of deferred income tax payments makes discounting very difficult to accomplish.

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

Alternative Minimum Tax. A tax that results from the use of an alternate determination of a corporation's federal income tax liability under provisions of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code.

Carrybacks. Deductions or credits that cannot be utilized on the tax return during a year that may be carried back to reduce taxable income or taxes payable in a prior year. An operating loss carryback is an excess of tax deductions over gross income in a year; a tax credit carryback is the amount by which tax credits available for utilization exceed statutory limitations. Different tax jurisdictions have different rules about whether excess deductions or credits may be carried back and the length of the carryback period.

Carryforwards. Deductions or credits that cannot be utilized on the tax return during a year that may be carried forward to reduce taxable income or taxes payable in a future year. An operating loss carryforward is an excess of tax deductions over gross income in a year; a tax credit carryforward is the amount by which tax credits available for utilization exceed statutory limitations. Different tax jurisdictions have different rules about whether excess deductions or credits may be carried forward and the length of the carryforward period. The terms carryforward, operating loss carryforward, and tax credit carryforward refer to the amounts of those items, if any, reported in the tax return for the current year.

Conduit bond obligor. The party on behalf of whom a state or local government agency raises funds by issuing bonds (commonly referred to as municipal bonds, industrial revenue bonds, or private activity bonds). Interest on the bonds typically is exempt from federal income tax to the investor, and in order to qualify for this exemption, the proceeds from the bond must be used by the conduit bond obligor for purposes permitted under the federal income tax code. If the proceeds from the bonds are used to provide funding to multiple parties that participate in a pool (a pooled conduit debt security), all of the individual conduit bond obligors that participate are considered individually to be conduit bond obligors.

Conduit debt securities. Certain limited-obligation revenue bonds, certificates of participation, or similar debt instruments issued by a state or local governmental entity (issuer) for the purpose of providing financing for a specific third party (the conduit bond obligor) that is not a part of the issuer's reporting entity. Even though these securities bear the issuer's name, the issuer often has no obligation with respect to the debt other than as provided in a lease or loan agreement with the conduit bond obligor on whose behalf the securities are issued. The conduit bond obligor is responsible for making or funding all principal and interest payments when due and is also responsible for future financial reporting requirements with respect to the securities.

Current Tax Expense (or Benefit). The amount of income taxes paid or payable (or refundable) for a year as determined by applying the provisions of the enacted tax law to the taxable income or excess of deductions over revenues for that year.

Deductible Temporary Difference. Temporary differences that result in deductible amounts in future years when the related asset or liability is recovered or settled, respectively.

Deferred Tax Asset. The deferred tax consequences attributable to deductible temporary differences and carryforwards. A deferred tax asset is measured using the applicable enacted tax rate and provisions of the enacted tax law. A deferred tax asset is reduced by a valuation allowance if, based on the weight of evidence available, it is more likely than not that some portion or all of a deferred tax asset will not be realized.

Deferred Tax Consequences. The future effects on income taxes as measured by the applicable enacted tax rate and provisions of the enacted tax law resulting from temporary differences and carryforwards at the end of the current year.

Deferred Tax Expense (or Benefit). The change during the year in an entity's deferred tax liabilities and assets. For deferred tax liabilities and assets acquired in a purchase business combination during the year, it is the change since the combination date. Income tax expense (or benefit) for the year is allocated among continuing operations, discontinued operations, extraordinary items, and items charged or credited directly to shareholders' equity.

Deferred Tax Liability. The deferred tax consequences attributable to taxable temporary differences. A deferred tax liability is measured using the applicable enacted tax rate and provisions of the enacted tax law.

Effective settlement. A conclusion, reached by applying criteria specified in ASC 740-10-25, that a taxing authority has in effect made its final determination with respect to the portion of a tax position, if any, that it will accept, and that management considers the possibility of further examination or reexamination of any aspect of the position to be remote.

Future deductible temporary difference. The difference between the GAAP carrying amount and income tax basis of an asset or liability that will reverse in the future and result in future income tax deductions; these give rise to deferred income tax assets.

Future taxable temporary difference. Temporary differences that result in future taxable amounts, which give rise to deferred income tax liabilities.

Gains and Losses Included in Comprehensive Income but Excluded from Net Income. Gains and losses included in comprehensive income but excluded from net income include certain changes in fair values of investments in marketable equity securities classified as noncurrent assets, certain changes in fair values of investments in industries having specialized accounting practices for marketable securities, adjustments related to pension liabilities or assets recognized within other comprehensive income, and foreign currency translation adjustments. Future changes to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) may change what is included in this category.

Highly certain income tax position. An income tax position that, based on clear and unambiguous tax law, rulings, regulations and interpretations, has a remote likelihood of being disallowed by the applicable taxing jurisdiction examining it with full possession of all relevant facts.

Income Tax Expense (or Benefit). The sum of current tax expense (or benefit) and deferred tax expense (or benefit).

Income tax position. Each judgment that management makes on an income tax return that has been or will be filed that affects the measurement of current or deferred income tax assets and liabilities at an interim or year-end date. The effects of taking an income tax position can result in a permanent reduction of income taxes payable or deferral of the payment of income taxes to a future year. The taking of an income tax position can also affect management's estimate of the valuation allowance sufficient to reflect the amount of deferred income tax assets that it believes will be realizable.

Interperiod tax allocation. The process of apportioning income tax expense among reporting periods without regard to the timing of the actual cash payments for income taxes. The objective is to reflect fully the income tax consequences of all economic events reported in current or prior financial statements and, in particular, to report the expected future income tax effects of the reversals of temporary differences existing at the reporting date.

Intraperiod tax allocation. The process of apportioning income tax expense applicable to a given period between income before extraordinary items and those items required to be shown net of tax such as extraordinary items, discontinued operations, and prior period adjustments.

Nexus. Nexus represents the types and extent of business activity that must be present before a state can impose an income tax on an entity. If an entity has nexus in a particular state, that entity is required to pay and collect/remit taxes in that state. In general, nexus is applied for income tax purposes if an entity derives income from sources within the state, owns or leases property in the state, employs personnel in the state in activities that exceed “mere solicitation,” or owns property located in the state. The amount of activity or connection that is necessary to create nexus is defined by each individual state's statute or case law and/or regulation, and thus is not uniform from state to state.

Nonpublic enterprise. An entity (1) whose debt or equity securities are not traded in a public market and (2) is not a conduit bond obligor for conduit debt securities traded in a public market. For the purpose of this definition, a public market can be a domestic or foreign exchange or over-the-counter market, even if the securities are only quoted locally or regionally. It is important to note that GAAP does not contain uniform definitions of public or nonpublic enterprises. Thus, the use of this terminology must be evaluated in the context of the specific standard in which it is used.

Operating loss carryback or carryforward. The excess of income tax deductions over taxable income. To the extent that this results in a carryforward, the income tax effect is included in the reporting entity's deferred income tax asset.

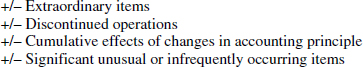

Ordinary income or loss (used in interim accounting for income taxes). In GAAP this term is defined differently than it is for income tax purposes. For GAAP purposes, ordinary income or loss is computed as pretax income (loss) from continuing operations less: (1) extraordinary items, (2) discontinued operations, (3) cumulative effects of changes in accounting principle, and (4) significant unusual or infrequently occurring items.

Permanent differences. Differences between pretax accounting income and taxable income as a result of the treatment accorded certain transactions by the income tax laws and regulations that differ from the accounting treatment. Permanent differences will not reverse in subsequent periods.

Pretax accounting income. Income or loss for the accounting period as determined in accordance with GAAP without regard to the income tax expense for the period.

Public enterprise. An entity (1) whose debt or equity securities are traded in a public market, (2) that is a conduit bond obligor for conduit debt securities traded in a public market, or (3) whose financial statements are filed with a regulatory agency in preparation for the sale of any class of securities. For the purpose of this definition, a public market can be a domestic or foreign exchange or over-the-counter market, even if the securities are only quoted locally or regionally. GAAP does not contain uniform definitions of public or nonpublic enterprises. Thus, the use of this terminology must be evaluated in the context of the specific standard in which it is used.

Tax (or Benefit). Tax (or benefit) is the total income tax expense (or benefit), including the provision (or benefit) for income taxes both currently payable and deferred.

Tax consequences. The effects on income taxes—current or deferred—of an event.

Tax credits. Reductions in income tax liability as a result of certain expenditures accorded special treatment under the Internal Revenue Code. Examples of such credits include: the Investment Tax Credit, investment in certain depreciable property; the Jobs Credit, payment of wages to targeted groups; the Research and Development Credit, an increase in qualifying R&D expenditures; and others.

Tax Position. A position in a previously filed tax return or a position expected to be taken in a future tax return that is reflected in measuring current or deferred income tax assets and liabilities for interim or annual periods. A tax position can result in a permanent reduction of income taxes payable, a deferral of income taxes otherwise currently payable to future years, or a change in the expected realizability of deferred tax assets. The term tax position also encompasses, but is not limited to:

- A decision not to file a tax return

- An allocation or a shift of income between jurisdictions

- The characterization of income or a decision to exclude reporting taxable income in a tax return

- A decision to classify a transaction, entity, or other position in a tax return as tax exempt

- An entity's status, including its status as a pass-through entity or a tax-exempt not-for-profit entity.

Taxable income. The difference between the taxable revenue and deductible expenses as defined by the Internal Revenue Code for a tax period without regard to special deductions (e.g., net operating loss or contribution carrybacks and carryforwards).

Taxable Temporary differences. Temporary differences that result in taxable amounts in future years when the related asset is recovered or the related liability is settled.

Tax-Planning Strategy. An action (including elections for tax purposes) that meets certain criteria (see paragraph 740-10-30-19) and that would be implemented to realize a tax benefit for an operating loss or tax credit carryforward before it expires. Tax-planning strategies are considered when assessing the need for and amount of a valuation allowance for deferred tax assets.

Unrecognized income tax benefits. The portion of income tax benefits claimed on income tax returns filed or to be filed for which, in management's judgment, realization would not be more than 50% probable should the income tax position be examined by the applicable taxing authority possessing all relevant information.

Unrelated business income. Income earned from a regularly carried-on trade or business that is not substantially related to the charitable, educational, or other purpose that is the basis of an organization's exemption from income taxes. This income subjects the otherwise tax-exempt organization to an entity-level unrelated business income tax (UBIT).

Valuation allowance. The contra asset that is to be reflected to the extent that, in management's judgment, it is “more likely than not” that the deferred income tax asset will not be realized.

CONCEPTS, RULES, AND EXAMPLES

Evolution of Accounting for Income Taxes

The differences in the timing of recognition of certain expenses and revenues for income tax reporting purposes versus the timing under GAAP had always been a subject for debates in the accounting profession. The initial debate was over the fundamental principle of whether or not income tax effects of timing difference should be recognized in the financial statements. At one extreme were those who believed that only the amount of income tax currently owed (as shown on the income tax return for the period) should be reported as periodic income tax expense, on the grounds that potential changes in tax law and the vagaries of the entity's future financial performance would make any projection to future periods speculative. This was the “no allocation” or “flow-through” position. At the other extreme were those who held that the matching principle demanded that reported periodic income tax expense be mechanically related to pretax accounting income, regardless of the amount of income taxes actually currently payable. This was the “comprehensive allocation” argument. The debate was settled in the late 1960s: comprehensive income tax allocation became GAAP.

The other key debate was over the measurement strategy to be applied to interperiod income tax allocation. When, in the 1960s and 1970s, accounting theory placed paramount importance on the income statement, with much less interest in the statement of financial position, the method of choice was the “deferred method,” which invoked the matching principle. The annual income tax provision (consisting of current and deferred portions) was calculated so that it would bear the expected relationship to pretax accounting income; any excess or deficiency of the income tax provision over income taxes payable was recorded as an adjustment to the deferred income tax amounts reflected on the statement of financial position. This practice, when applied, resulted in a net deferred income tax debit (subject to some limitations on asset realization) or a net deferred income tax credit, which did not necessarily mean that an asset or liability, as defined under GAAP, actually existed for that reported amount.

By the late 1970s, accounting theory made the financial reporting priority the statement of financial position. Primary emphasis was placed on the measurement of assets and liabilities—which, under CON 6's definitions, clearly would not include certain deferred income tax benefits or obligations as these were then measured. To compute deferred income taxes consistent with this orientation requires use of the “liability method.” This essentially ascertains, as of each date for which a statement of financial position is presented, the amount of future income tax benefits or obligations that are associated with the reporting entity's assets and liabilities existing at that time. Any adjustments necessary to increase or decrease deferred income taxes to the computed balance, plus or minus the amount of income taxes owed currently, determines the periodic income tax expense or benefit to be reported in the income statement. Put another way, income tax expense is the residual result of several other computations oriented to measurement in the statement of financial position.

ASC 740 required that all deferred income tax assets are given full recognition, whether arising from deductible temporary differences or from net operating loss or tax credit carryforwards.

Under ASC 740 it is necessary to assess whether the deferred income tax asset is realizable. Testing for realization is accomplished by means of a “more-likely-than-not” criterion that indicates whether an allowance is needed to offset some or all of the recorded deferred income tax asset. While the determination of the amount of the allowance may make use of the scheduling of future expected reversals, other methods may also be employed.

In summary, interperiod income tax allocation under GAAP is currently based on the liability method, using comprehensive allocation. While this basic principle may be straightforward, there are a number of computational complexities to be addressed. These will be presented in the remainder of this chapter.

An example of application of the liability method of deferred income tax accounting follows.

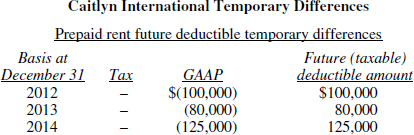

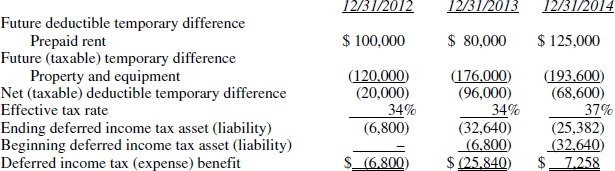

Caitlyn International has no permanent differences in years 2012 through 2014 (these are discussed later in this chapter). The company has only two amounts on its statement of financial position with temporary differences between their income tax and financial reporting bases, property and equipment; and prepaid rent. No consideration is given to the classification of the deferred income tax amounts (i.e., current or long-term) as it is not considered necessary for purposes of this example.

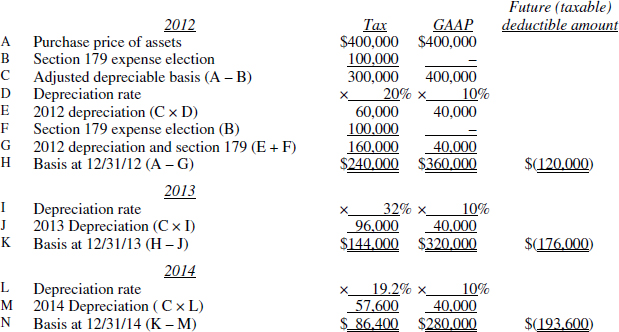

Details of Caitlyn's temporary differences are as follows:

Property and equipment future taxable temporary difference

On January 1, 2012, Caitlyn International purchased $400,000 of property and equipment with a 10-year estimated useful life which, under its normal accounting policy, it depreciates using the straight-line method. For income tax purposes, these assets qualify as 5-year personal property under the General Depreciation System (GDS), and consequently, income tax depreciation is computed using the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) which is equivalent to double-declining balance depreciation with a half-year assumed for the year placed in service and changing to straight-line depreciation when advantageous to the taxpayer. In addition, as permitted by IRC Section 179, Caitlyn elected to deduct $100,000 of these costs in the year placed in service. By making this election, for the purpose of computing income tax cost recovery, Caitlyn is required to reduce the depreciable basis of the eligible assets by the amount of Section 179 deduction taken during the tax year.

The computation of deferred income taxes is as follows:

Note from the computations that, under the liability method, deferred income tax expense or benefit is the amount necessary to adjust the statement of financial position to the computed balance. No attempt is made to correlate the amount of deferred income tax expense or benefit to pretax accounting income or loss. Nor is it necessary to track the amount of each temporary difference that originates or reverses during the year.

ASC 740 in Greater Detail

While the liability method is conceptually straightforward, in practice there are a number of complexities to be addressed. Income tax accounting remains one of the more difficult areas of accounting practice. In the following pages, these measurement and reporting issues will be discussed in greater detail:

- Temporary and permanent differences

- Treatment of net operating loss carryforwards

- Measurement of deferred income tax assets and liabilities

- Considering whether a valuation allowance is needed

- The effect of tax law changes on previously recorded deferred income tax assets and liabilities

- The effect of a change in the tax status of the reporting entity from taxable to non-taxable or vice versa on previously recognized deferred income tax assets and liabilities

- The effect of accounting changes for income tax purposes

- Income tax effects of dividends paid on shares held by Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOP)

- The income tax effects of business combinations at and after acquisition date

- Intercorporate income tax allocation

- Separate financial statements of subsidiaries or investees

- Asset acquisitions

- Intraperiod income tax allocation

- Classification in the statement of financial position

- Disclosures

- Interim reporting.

Detailed examples of deferred income tax accounting under ASC 740 are presented throughout the following discussion of these issues.

Temporary and Permanent Differences

Deferred income taxes are provided for all temporary differences, but not for permanent differences. Thus, it is important to be able to distinguish between the two.

Temporary differences.

While many typical business transactions are accounted for identically for income tax and financial reporting purposes, there are many others subject to different income tax and accounting treatments, often leading to their being reported in different periods in financial statements than they are reported on income tax returns. The term “timing differences,” used under prior GAAP, has been superseded by the broader term “temporary differences” under current rules. Under income statement-oriented GAAP, timing differences were said to originate in one period and to reverse in a later period. These involved such common items as alternative depreciation methods, deferred compensation plans, percentage-of-completion accounting for long-term construction contracts, and cash basis versus accrual basis accounting.

The more comprehensive concept of temporary differences, consistent with modern GAAP, includes all differences between the income tax basis and the financial reporting carrying value of assets and liabilities, if the reversal of those differences will result in taxable or deductible amounts in future years. Temporary differences include all the items formerly defined as timing differences, and other additional items.

Temporary differences under ASC 740 that were defined as timing differences under prior GAAP can be categorized as follows:

Revenue recognized for financial reporting purposes before being recognized for income tax purposes. Revenue accounted for by the installment method for income tax purposes, but fully reflected in current GAAP income; certain construction-related revenue recognized using the completed-contract method for income tax purposes, but recognized using the percentage-of-completion method for financial reporting purposes; earnings from investees recognized using the equity method for accounting purposes but taxed only when later distributed as dividends to the investor. These are future taxable temporary differences because future periods' taxable income will exceed GAAP income as the differences reverse; thus they give rise to deferred income tax liabilities.

Revenue recognized for income tax purposes prior to recognition in the financial statements. Certain taxable revenue received in advance, such as prepaid rental income and service contract revenue not recognized in the financial statements until later periods. These are future deductible temporary differences, because the costs of future performance will be deductible in the future years when incurred without being reduced by the amount of revenue deferred for GAAP purposes. Consequently, the income tax benefit to be realized in future years from deducting those future costs is a deferred income tax asset.

Expenses deductible for income tax purposes prior to recognition in the financial statements. Accelerated depreciation methods or shorter statutory useful lives used for income tax purposes, while straight-line depreciation or longer useful economic lives are used for financial reporting; amortization of goodwill and nonamortizable intangible assets over a 15-year life for income tax purposes while not amortizing them for financial reporting purposes unless they are impaired. Upon reversal in the future, the effect would be to increase taxable income without a corresponding increase in GAAP income. Therefore, these items are future taxable temporary differences, and give rise to deferred income tax liabilities.

Expenses recognized in the financial statements prior to becoming deductible for income tax purposes. Certain estimated expenses, such as warranty costs, as well as such contingent losses as accruals of litigation expenses, are not tax deductible until the obligation becomes fixed. In those future periods, those expenses will give rise to deductions on the reporting entity's income tax return. Thus, these are future deductible temporary differences that give rise to deferred income tax assets.

In addition to these familiar and well-understood categories of timing differences, temporary differences include a number of other categories that also involve differences between the income tax and financial reporting bases of assets or liabilities. These include:

Reductions in tax-deductible asset bases arising in connection with tax credits. Under the provisions of the 1982 income tax act, taxpayers were permitted a choice of either full ACRS depreciation coupled with a reduced investment tax credit, or a full investment tax credit coupled with reduced depreciation allowances. If the taxpayer chose the latter option, the asset basis was reduced for tax depreciation, but was still fully depreciable for financial reporting purposes. Accordingly, this type of election is accounted for as a future taxable temporary difference, which gives rise to a deferred income tax liability.

Increases in the income tax bases of assets resulting from the indexing of asset costs for the effects of inflation. Occasionally proposed but never enacted, enacting such a provision to income tax law would allow taxpaying entities to finance the replacement of depreciable assets through depreciation based on current costs, as computed by the application of indices to the historical costs of the assets being remeasured. This reevaluation of asset costs would give rise to future taxable temporary differences that would be associated with deferred income tax liabilities since, upon the eventual sale of the asset, the taxable gain would exceed the gain recognized for financial reporting purposes resulting in the payment of additional tax in the year of sale.

Certain business combinations accounted for by the purchase method or the acquisition method. Under certain circumstances, the amounts assignable to assets or liabilities acquired in business combinations will differ from their income tax bases. Such differences may be either taxable or deductible in the future and, accordingly, may give rise to deferred income tax liabilities or assets. These differences are explicitly recognized by the reporting of deferred income taxes in the consolidated financial statements of the acquiring entity. Note that these differences are no longer allocable to the financial reporting bases of the underlying assets or liabilities themselves, as was the case under the old net of tax method.

A financial reporting situation in which deferred income taxes may or may not be appropriate would include life insurance (such as key person insurance) under which the reporting entity is the beneficiary. Since proceeds of life insurance are not subject to income tax under present law, the excess of cash surrender values over the sum of premiums paid will not be a temporary difference under the provisions of ASC 740, if the intention is to hold the policy until death benefits are received. On the other hand, if the entity intends to cash in (surrender) the policy at some point prior to the death of the insured (i.e., it is holding the insurance contract as an investment), which would be a taxable event, then the excess surrender value is in fact a temporary difference, and deferred income taxes are to be provided thereon.

Temporary differences from share-based compensation arrangements.

ASC 718-50 contains intricate rules with respect to accounting for the income tax effects of different types of share-based compensation awards.

The complexity of applying the income tax provisions contained in ASC 718-50 is exacerbated by the complex statutes and regulations that apply under the US Internal Revenue Code (IRC). The American Job Creation Act of 2004 added IRC §409A, which contains complicated provisions regarding the timing of taxability of specified amounts deferred under nonqualified deferred compensation plans. In general, amounts deferred under specified types of nonqualified plans are currently includable in gross income to the extent the benefits are not subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture unless certain requirements are met. An incentive stock option (ISO or statutory option governed by IRC §422) is not subject to §409A; however, certain nonqualified stock option (NQSO or nonstatutory) plans are subject to these requirements.

Differences between the accounting rules and the income tax laws can result in situations where the cumulative amount of compensation cost recognized for financial reporting purposes will differ from the cumulative amount of compensation deductions recognized for income tax purposes. Under current income tax law applicable to certain NQSO awards, an employer recognizes an income tax deduction for the intrinsic value of the option on the date that the employee exercises the option. The intrinsic value is computed as the difference between the option's exercise price and the market price of the stock on the date of exercise. Under ASC 718-50 this type of equity award is recognized at the fair value of the options at grant date with compensation cost recognized over the requisite service period. Consequently, during the period from grant date until the end of the requisite service period, the reporting entity is recognizing compensation cost in its financial statements with no corresponding income tax deduction. Because the award described above is accounted for as equity (and not as a liability), the credit that offsets the debit to compensation cost is to additional paid-in capital. This results in a future deductible temporary difference between the carrying amounts of additional paid-in capital for financial reporting and income tax purposes, thus giving rise to a deferred income tax asset and corresponding deferred income tax benefit.

At exercise, to the extent that the income tax deduction based on intrinsic value exceeds the cumulative compensation cost recognized for financial reporting purposes, the income tax effect (the effective income tax rate multiplied by the cumulative difference) is credited to additional paid-in capital rather than being reflected in the income statement as a deferred income tax benefit.

The IRC provides employers the ability to obtain a current income tax deduction for payments of dividends (or dividend equivalents) to employees that hold nonvested shares, share units, or share options that are classified under ASC 718-50 as equity. Under this scenario, the payment of the dividends is charged to retained earnings under ASC 718-50, irrespective of the fact that the employer/reporting entity obtains a tax deduction for the payment as taxable compensation. The income tax benefit realized from deducting these payments is to be recorded as an increase to additional paid-in capital and, as explained in the discussion of ASC 718-50 in the chapter on ASC 718, included in the pool of excess tax benefits available to absorb tax deficiencies on share-based payment awards.

Temporary differences arising from convertible debt with a beneficial conversion feature.

Issuers of debt securities sometimes structure the instruments to include a nondetachable conversion feature. If the terms of the conversion feature are “in-the-money” at the date of issuance, the feature is referred to as a “beneficial conversion feature.” Beneficial conversion features are accounted for separately from the host instrument under ASC 470-20.

The separate accounting results in an allocation to additional paid-in capital of a portion of the proceeds received from issuance of the instrument that represents the intrinsic value of the conversion feature calculated at the commitment date, as defined. The intrinsic value is the difference between the conversion price and the fair value of the instruments into which the security is convertible multiplied by the number of shares into which the security is convertible. The convertible security is recorded at its par value (assuming there is no discount or premium on issuance). A discount is recognized to offset the portion of the instrument that is allocated to additional paid-in capital. The discount is accreted from the issuance date to the stated redemption date of the convertible instrument or through the earliest conversion date if the instrument does not include a stated redemption date.

For US income tax purposes, the proceeds are recorded entirely as debt and represent the income tax basis of the debt security, thus creating a temporary difference between the basis of the debt for financial reporting and income tax reporting purposes.

ASC 740-10-55 specifies that the income tax effect associated with this temporary difference is to be recorded as an adjustment to additional paid-in-capital. It would not be reported, as are most other such income tax effects, as a deferred income tax asset or liability in the statement of financial position.

Other common temporary differences include:

Accounting for investments. Use of the equity method for financial reporting while using the cost method for income tax purposes.

Accrued contingent liabilities. These cannot be deducted for income tax purposes until the liability becomes fixed and determinable.

Cash basis versus accrual basis. Use of the cash method of accounting for income tax purposes and the accrual method for financial reporting.

Charitable contributions that exceed the statutory deductibility limitation. These can be carried over to future years for income tax purposes.

Deferred compensation. Under GAAP, the present value of deferred compensation agreements must be accrued and charged to expense over the employee's remaining employment period, but for income tax purposes these costs are not deductible until actually paid.

Depreciation. A temporary difference will occur unless the modified ACRS method is used for financial reporting over estimated useful lives that are the same as the IRS-prescribed recovery periods. This is only permissible for GAAP if the recovery periods are substantially identical to the estimated useful lives.

Estimated costs (e.g., warranty expense). Estimates or provisions of this nature are not included in the determination of taxable income until the period in which the costs are actually incurred.

Goodwill. For US federal income tax purposes, amortization over fifteen years is mandatory. Amortization of goodwill is no longer permitted under GAAP, but periodic write-downs for impairment may occur, with any remainder of goodwill being expensed when the reporting unit to which it pertains is ultimately disposed of.

Income received in advance (e.g., prepaid rent). Income of this nature is includable in taxable income in the period in which it is received, while for financial reporting purposes, it is considered a liability until the revenue is earned.

Installment sale method. Use of the installment sale method for income tax purposes generally results in a temporary difference because that method is generally not permitted to be used in accordance with GAAP.

Long-term construction contracts. A temporary difference will arise if different methods (e.g., completed-contract or percentage-of-completion) are used for GAAP and income tax purposes.

Mandatory change from the cash method to the accrual method. Generally one-fourth of this adjustment is recognized for income tax purposes each year.

Net capital loss. C corporation capital losses are recognized currently for financial reporting purposes but are carried forward to be offset against future capital gains for income tax purposes.

Organization costs. GAAP requires organization costs to be treated as expenses as incurred. For income tax purposes, organization costs are recorded as assets and amortized over a 60-month period. Also see the following section, “Permanent differences.”

Uniform cost capitalization (UNICAP). Income tax accounting rules require manufacturers and certain wholesalers to capitalize as inventory costs certain costs that, under GAAP, are considered administrative costs that are not allocable to inventory.

Permanent differences.

Permanent differences are book-tax differences in asset or liability bases that will never reverse and therefore, affect income taxes currently payable but do not give rise to deferred income taxes.

Common permanent differences include:

Club dues. Dues assessed by business, social, athletic, luncheon, sporting, airline and hotel clubs are not deductible for federal income tax purposes.

Dividends received deduction. Depending on the percentage interest of the payer owned by the recipient, a percentage of the dividends received by a corporation are nontaxable. Different rules apply to subsidiaries.

Goodwill—nondeductible. If, in a particular taxing jurisdiction, goodwill amortization is not deductible, that goodwill is considered a permanent difference and does not give rise to deferred income taxes.

Lease inclusion amounts. Lessees of automobiles whose fair value the IRS deems to qualify as a luxury automobile are required to limit their lease deduction by adding to taxable income an amount determined by reference to a table prescribed annually in a revenue procedure.

Meals and entertainment. A percentage (currently 50%) of business meals and entertainment costs are not deductible for federal income tax purposes.

Municipal interest income. A 100% exclusion is permitted for investment in qualified municipal securities. Note that the capital gains applicable to sales of these securities are taxable.

Officer's life insurance premiums and proceeds. Premiums paid for an officer's life insurance policy under which the company is the beneficiary are not deductible for income tax purposes, nor are any death proceeds taxable.

Organization and start-up costs. GAAP requires organization and start-up costs to be treated as expenses as incurred. Certain organization and start-up costs are not allowed amortization under the tax code. The most clearly defined are those expenditures relating to the cost of raising capital. Also see the prior section, “Temporary differences. . . .”

Penalties and fines. Any penalty or fine arising as a result of violation of the law is not allowed as an income tax deduction. This includes a wide range of items including parking tickets, environmental fines, and penalties assessed by the US Internal Revenue Service.

Percentage depletion. The excess of percentage depletion over cost depletion is allowable as a deduction for income tax purposes.

Wages and salaries eligible for jobs credit. The portion of wages and salaries used in computing the jobs credit is not allowed as a deduction for income tax purposes.

Treatment of Net Operating Loss Carryforwards

The recognition and measurement of the income tax effects of net operating loss carryforwards under ASC 740 differ materially from how this was dealt with under earlier standards. Historically, it had been presumed that net operating losses would generally not be realizable; accordingly, the income tax effects of carryforwards were not recognized in the financial statements until the future period in which the benefits were realized for income tax purposes. That is, the provision for income taxes in the loss year only reflected the benefit derived, if any, from carrying back the net operating loss to prior years to obtain a refund. Any excess net operating loss available to offset future years' taxable income was not recognized until actually realized. Consequently, the statement of financial position would not display a deferred income tax asset relating to the net operating loss carryforward. This treatment was justified in order to report the entity's assets at amounts that did not exceed their estimated net realizable value. (Only in exceptional cases, when realization of the benefits was deemed to be assured beyond a reasonable doubt, was recognition in the loss period permitted.)

With the imposition of ASC 740, all temporary differences and carryforwards have been conferred identical status, and their income tax effects are to be given full recognition on the statement of financial position. Specifically, the income tax effects of net operating loss carryforwards are equivalent to the income tax effects of future deductible temporary differences, and the once important distinction between the two has been eliminated. The deferred income tax effects of net operating losses are computed and recorded, but as is the case for all other deferred income tax assets, the need for a valuation allowance must also be assessed (as discussed below). The income tax effects of income tax credit carryforwards (e.g., general business credits, alternative minimum tax credits) are used to increase deferred income tax assets dollar-for-dollar versus being treated in the same manner as future deductible temporary differences, as illustrated in the following example.

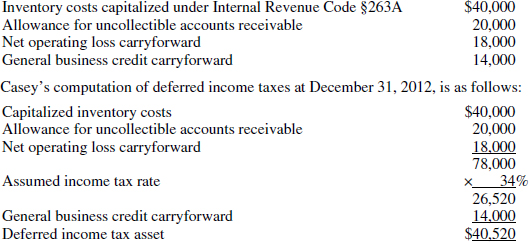

Casey Corporation has the following future deductible temporary differences and available carryforwards at December 31, 2012:

Note the net operating loss is multiplied by the income tax rate to compute its effect on the deferred income tax asset since it is available to reduce future years' taxable income. In contrast, the general business credit carryforward is not multiplied by the income tax rate since it is available to be used to offset future years' income tax.

The reporting of the current income tax benefit of carrying back net operating losses was also changed by the current standard. ASC 740 provides that the income tax benefits of net operating loss carrybacks and carryforwards, with limited exceptions (discussed below), are to be reported in the same manner as the source of either income or loss in the current year. As used in the standard, the phrase “in the same manner” refers to the classification of the income tax benefit in the income statement (i.e., as income taxes on income from continuing operations, discontinued operations, extraordinary items, etc.) or as the income tax effect of gains included in other comprehensive income but excluded from net income on the income statement. The income tax benefits are not reported in the same manner as the source of the net operating loss carryforward or income taxes paid in a prior year, or as the source of the expected future taxable income that will permit the realization of the carryforward.

For example, if the income tax benefit of a loss that arose in a prior year in connection with an extraordinary item is first given recognition in the current year, the benefit would be allocated to income taxes on income from continuing operations if the benefit offsets income taxes on income from continuing operations in the current year. The expression “first given recognition” means that the net deferred income tax asset, after deducting the valuation allowance, reflects the income tax effect of the loss carryforward for the first time.

Under ASC 740, the gross deferred income tax asset will always reflect all future deductible temporary differences and net operating loss carryforwards in the periods they arise. Thus, first given recognition means that the valuation allowance is eliminated for the first time. If it offsets income taxes on extraordinary income in the current year, then the benefits would be reported in extraordinary items. As another example, the tax benefit arising from the entity's loss from continuing operations in the current year would be allocated to continuing operations, regardless of whether it might be realized as a carryback against income taxes paid on extraordinary items in prior years. The income tax benefit would also be allocated to continuing operations in cases where it is anticipated that the benefit will be realized through the reduction of income taxes to be due on extraordinary gains in future years. (See the “Intraperiod Income Tax Allocation” section later in this chapter.)

Thus, the general rule is that the reporting of income tax effects of net operating losses are driven by the source of the tax benefits in the current period. There are only two exceptions to the foregoing rule. The first exception relates to existing future deductible temporary differences and net operating loss carryforwards that arise in connection with business combinations and for which income tax benefits are first recognized. This exception will be discussed below (see income tax effects of business combinations). As in the preceding paragraph, first recognized means that a valuation allowance (as discussed more fully later in this chapter) provided previously is being eliminated for the first time.

The second exception to the aforementioned general rule is that certain income tax benefits allocable to stockholders' equity are not to be reflected in the income statement. Specifically, income tax benefits arising in connection with contributed capital, employee stock options, dividends paid on unallocated ESOP shares, or temporary differences existing at the date of a quasi reorganization are reported as accumulated other comprehensive income in the stockholders' equity section of the statement of financial position and are not included in the income statement.

Certain transactions among stockholders that occur outside the company can affect the status of deferred income taxes. The most commonly encountered of these is the change in ownership of more than 50% of the company's stock, which limits or eliminates the company's ability to utilize net operating loss carryforwards, and accordingly requires the reversal of deferred income tax assets previously recognized under ASC 740. Changes in deferred income taxes caused by transactions among stockholders are to be included in current period income tax expense in the income statement, since these are analogous to changes in expectations resulting from other external events (e.g., changes in enacted income tax rates). However, the income tax effects of changes in the income tax bases of assets or liabilities caused by transactions among stockholders would be included in equity, not in the income statement, although subsequent period changes in the valuation account, if any, would be reflected in income (ASC 740-20-45).

Measurement of Deferred Income Tax Assets and Liabilities

Scheduling of the reversal years of temporary differences.

Under ASC 740 there is no need to forecast (or “schedule”) the future years in which temporary differences are expected to reverse except in the most exceptional circumstances. To eliminate the burden, it was necessary to endorse the use of the expected average (i.e., effective) income tax rate to measure the deferred income tax assets and liabilities and to forgo a more precise measure of marginal tax effects. Scheduling is now encountered primarily (1) when income tax rate changes are to be phased in over multiple years, and (2) in order to determine the classification (current or noncurrent) of a deferred income tax asset arising from a net operating loss carryforward or income tax credit carryforward or to determine whether such a carryforward might expire unused for the purpose of determining the amount of valuation allowance needed (as discussed in the following section of this chapter).

Determining the appropriate income tax rate.

Currently, C corporations with taxable income between $335,000 and $10,000,000 are taxed at an expected income tax rate equal to the 34% marginal rate, since the effect of the surtax exemption has fully phased out at that level, effectively resulting in a flat tax. Thus, the computation of deferred federal income taxes for these entities is accomplished simply by applying the 34% top marginal rate to all temporary differences and net operating loss carryforwards outstanding at the date of the statement of financial position. This technique is applied to future taxable temporary differences (producing deferred income tax liabilities), and to future deductible temporary differences and net operating loss carryforwards (giving rise to deferred income tax assets). The deferred income tax assets computed must still be evaluated for realizability; some, or all, of the projected income tax benefits may fail the “more-likely-than-not” test and consequently may need to be offset by a valuation allowance.

On the other hand, reporting entities that have historically been taxed at an effective federal income tax rate lower than the top marginal rate compute their federal deferred income tax assets and liabilities by using their expected future effective income tax rates. Consistent with the goal of simplifying the process of calculating deferred income taxes, reporting entities are permitted to apply a single, long-term expected income tax rate, without attempting to differentiate among the years when temporary difference reversals are expected to occur. In any event, the inherent imprecision of forecasting future income levels and the patterns of temporary difference reversals makes it unlikely that a more sophisticated computational effort would produce better financial statements. Therefore, absent such factors as the phasing in of new income tax rates, it is not necessary to consider whether the reporting entity's effective income tax rate will vary from year to year.

The effective income tax rate convention obviates the need to predict the impact of the alternative minimum tax (AMT) on future years. In determining an entity's deferred income taxes, the number of computations may be as few as one.

Computing deferred income taxes.

The procedure to compute the gross deferred income tax provision (i.e., before addressing the possible need for a valuation allowance) is as follows:

- Identify all temporary differences existing as of the reporting date. This process is simplified if the reporting entity maintains both GAAP and income tax statements of financial position for comparison purposes.

- Segregate the temporary differences into future taxable differences and future deductible differences. This step is necessary because a valuation allowance may be required to be provided to offset the income tax effects of the future deductible temporary differences and carryforwards, but not the income tax effects of the future taxable temporary differences.

- Accumulate information about available net operating loss and tax credit carryforwards as well as their expiration dates or other types of limitations, if any.

- Measure the income tax effect of aggregate future taxable temporary differences by separately applying the appropriate expected income tax rates (federal plus any state, local, and foreign rates that are applicable under the circumstances). Ensure that consideration is given in making these computations to the federal income tax deductibility of income taxes payable to other jurisdictions.

- Similarly, measure the income tax effects of future deductible temporary differences, including net operating loss carryforwards.

ASC 740 prescribes that separate computations be made for each taxing jurisdiction. In many cases, this level of complexity is not needed and a single, combined effective income tax rate can be used. However, in assessing the need for valuation allowances, it is necessary to consider the entity's ability to absorb deferred income tax benefits against income tax liabilities. Inasmuch as benefits from one tax jurisdiction will not reduce income taxes payable to another tax jurisdiction, separate calculations will be needed in these situations. Also, for purposes of presentation in the statement of financial position (discussed below), offsetting of deferred income tax assets and liabilities is only permissible within the same jurisdiction.

Separate computations are made for each taxpaying component of the primary reporting entity: if a parent company and its subsidiaries are consolidated for financial reporting purposes but file separate income tax returns, the reporting entity comprises a number of components, and the income tax benefits of any one will be unavailable to reduce the income tax obligations of the others.

The principles set forth above are illustrated by the following example.

Assume that Humfeld Company has a total of $28,000 of future taxable temporary differences and a total of $8,000 of future deductible temporary differences. There are no available operating loss or tax credit carryforwards. Taxable income is $230,000 and the income tax rate is a flat (i.e., not graduated) 34% for the current year and not anticipated to change in the future. Also assume that there were no deferred income tax liabilities or assets in prior years.

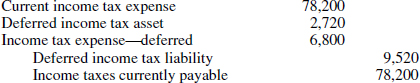

Current income tax expense and income taxes currently payable are computed as taxable income times the current rate ($230,000 × 34% = $78,200). The deferred income tax asset is computed as $2,720, representing 34% of future deductible temporary differences of $8,000. The deferred income tax liability of $9,520 is calculated as 34% of future taxable temporary differences of $28,000. The deferred income tax expense of $6,800 is the net of the deferred income tax liability of $9,520 and the deferred income tax asset of $2,720.

The journal entry to record the required amounts is:

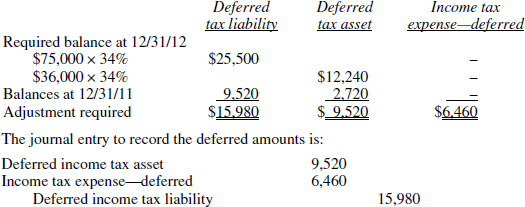

In 2011, Humfeld Company has taxable income of $411,000, aggregate future taxable and future deductible temporary differences are $75,000 and $36,000 respectively, and the income tax rate remains a flat 34%.

Current income tax expense and income taxes currently payable are each $139,740 ($411,000 × 34%).

Deferred amounts are calculated as follows:

Because the increase in the liability in 2012 is larger (by $6,460) than the increase in the asset for that year, the result is a deferred income tax expense for 2012.

The Valuation Allowance for Deferred Income Tax Assets Expected to Be Unrealizable

ASC 740 requires that all deferred income tax assets be given full recognition, subject to the possible provision of an allowance when it is determined that this asset is unlikely to be realized. This approach (providing full recognition on a gross basis, but also providing for a valuation allowance to reduce the recorded asset to the expected realizable amount) conveys the greatest amount of useful information to the users of the financial statements.

In dealing with the question of measurement of the valuation account, FASB could well have been guided by ASC 450, which established the standard for recognizing contingent obligations incurred and impairments of assets. Under ASC 450, the threshold for recognition of impairment would have been that the impairment was deemed to be “probable” of realization. FASB rejected the notion of applying that standard to this measurement situation, and instead developed a new measure, the “more-likely-than-not” criterion.

Under this provision of ASC 740, a valuation allowance is to be provided for that fraction of the computed year-end balances of the deferred income tax assets for which it has been determined that it is more likely than not that the reported asset amount will not be realized. As used in this context, “more likely than not” represents a probability of just over 50%. Since it is widely agreed that the term probable, as used in ASC 450, denotes a much higher probability (perhaps 85% to 90%), the threshold for reflecting an impairment of deferred income tax assets is much lower than the threshold for other assets (i.e., in most cases, the likelihood of a valuation allowance being required is greater than, say, the likelihood that a long-lived asset is impaired).

If a higher threshold had been set (such as ASC 450's “probable”), great diversity could have developed in practice as to the amount of valuation allowances offsetting deferred income tax assets, which would not have been consistent with the goal of comparability of financial statements over time and across entities.

Assume that Couch Corporation has a future deductible temporary difference of $60,000 at December 31, 2012. The tax rate is a flat 34%. Based on available evidence, management of Couch Corporation concludes that it is more likely than not that all sources will not result in future taxable income sufficient to realize an income tax benefit of more than $15,000 (25% of the future deductible temporary difference). Also assume that there were no deferred income tax assets in previous years and that prior years' taxable income was inconsequential.

At 12/31/12 Couch Corporation records a deferred income tax asset in the amount of $20,400 ($60,000 × 34%) and a valuation allowance of $15,300 (34% of the $45,000 difference between the $60,000 of future deductible temporary differences and the $15,000 of future taxable income expected to absorb the future tax deduction arising from the reversal of the temporary difference).

The journal entry at 12/31/12 is

![]()

The deferred income tax benefit of $5,100 represents that portion of the deferred income tax asset (25%) that, more likely than not, is realizable.

Assume that at the end of 2013, Couch Corporation's future deductible temporary difference has decreased to $50,000 and that Couch now has a net operating loss carryforward of $42,000. The total of the net operating loss carryforward ($42,000) plus the amount of the future deductible temporary difference ($50,000) is $92,000. A deferred income tax asset of $31,280 ($92,000 × 34%) is recognized at the end of 2013. Also assume that management of Couch Corporation concludes that it is more likely than not that $25,000 of the tax asset will not be realized. Thus, a valuation allowance in that amount is required, and the balance in the allowance account of $15,300 must be increased by $9,700 ($25,000 − $15,300).

The journal entry at 12/31/13 is

![]()

The deferred income tax asset is debited $10,880 to increase it from $20,400 at the end of 2012 to its required balance of $31,280 at the end of 2013. The deferred income tax benefit of $1,180 represents the net of the $10,880 increase in the deferred income tax asset and the $9,700 increase in the valuation allowance.

While the meaning of the “more likely than not” criterion is clear (more than 50%), the practical difficulty of assessing whether or not this subjective threshold test is met in a given situation remains. A number of positive and negative factors need to be evaluated in reaching a conclusion as to the necessity of a valuation allowance. Positive factors (those suggesting that an allowance is not necessary) include:

- Evidence of sufficient future taxable income, exclusive of reversing temporary differences and carryforwards, to realize the benefit of the deferred income tax asset

- Evidence of sufficient future taxable income arising from the reversals of existing future taxable temporary differences (deferred income tax liabilities) to realize the benefit of the deferred income tax asset

- Evidence of sufficient taxable income in prior year(s) available for realization of a net operating loss carryback under existing statutory limitations

- Evidence of the existence of prudent, feasible tax planning strategies under management control that, if implemented, would permit the realization of the deferred income tax asset

- An excess of appreciated asset values over their tax bases, in an amount sufficient to realize the deferred income tax asset

- A strong earnings history exclusive of the loss creating the deferred tax asset.

While the foregoing may suggest that the reporting entity will be able to realize the benefits of the future deductible temporary differences outstanding as of the date of the statement of financial position, certain negative factors must also be considered in determining whether a valuation allowance needs to be established against deferred income tax assets. These factors include:

- A cumulative recent history of losses

- A history of operating losses, or of net operating loss or tax credit carryforwards that have expired unused

- Losses that are anticipated in the near future years, despite a history of profitable operations.

Thus, the process of evaluating whether a valuation allowance is needed involves the weighing of both positive and negative factors to determine whether, based on the preponderance of available evidence, it is more likely than not that the deferred income tax assets will be realized.

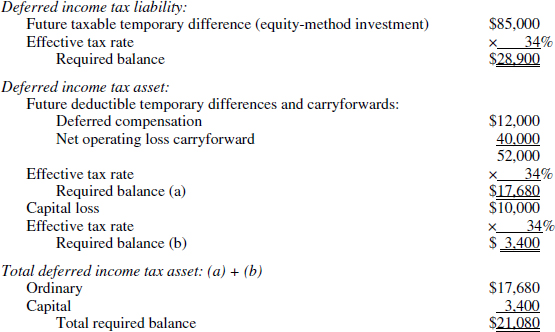

Assume the following facts:

- Foy Corporation reports on a calendar year, and it commenced operations and began applying ASC 740 in 2006.

- As of December 31, 2012, it has future taxable temporary differences of $85,000 relating to income earned on equity-method investments; future deductible temporary differences of $12,000 relating to deferred compensation arrangements; a net operating loss carryforward (which arose in 2009) of $40,000; and a capital loss carryforward of $10,000 (which arose in 2012).

- Foy's expected effective income tax rate for future years is 34% for both ordinary income and net long-term capital gains. Capital losses cannot be offset against ordinary income.

The first steps are to compute the deferred income tax asset and/or liability without consideration of the possible need for a valuation allowance.

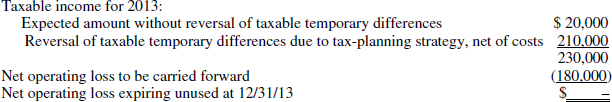

The next step is to consider the need for a valuation allowance to partially or completely offset the deferred income tax asset, based on a “more likely than not” assessment of the asset's realizability. Foy management must evaluate both positive and negative evidence to determine the need for a valuation allowance, if any. Assume that management identifies the following factors that may affect this need:

- Before the net operating loss deduction, Foy reported taxable income of $5,000 in 2012. Management believes that taxable income in future years, apart from net operating loss deductions, should continue at approximately the same level experienced in 2012.

- The future taxable temporary differences are not expected to reverse in the foreseeable future as the equity method investee is not expected to incur losses or pay dividends to Foy.

- The capital loss arose in connection with a securities transaction of a type that is unlikely to recur. The company does not generally engage in activities that have the potential to result in capital gains or losses.

- Management estimates that certain productive assets have a fair value exceeding their respective income tax bases by about $30,000. The entire gain, if realized for income tax purposes, would result in recapture of depreciation previously taken. Since the current plans call for a substantial upgrading of the company's plant assets, management feels it could easily accelerate those actions in order to realize taxable gains, should it be desirable to do so for income tax planning purposes.

Based on the foregoing information, Foy Corporation management concludes that a $3,400 valuation allowance is required. The reasoning is as follows:

- There will be some taxable operating income generated in future years ($5,000 annually, based on the earnings experienced in 2012), which will absorb a modest portion of the reversal of the deductible temporary difference ($12,000) and net operating loss carryforward ($40,000) existing at year-end 2012.

- More importantly, the feasible tax planning strategy of accelerating the taxable gain relating to appreciated assets ($30,000) would certainly be sufficient, in conjunction with operating income over several years, to permit Foy to fully realize the income tax benefits of the future deductible temporary difference and net operating loss carryover.

- However, since capital losses can only be carried forward for five years, are only usable to offset future capital gains, and Foy management is unable to project future realization of capital gains, it is more likely than not that the associated tax benefit accrued ($3,400) will not be realized, and thus a valuation allowance must be recorded.

Based on this analysis, an allowance for unrealizable deferred income tax benefits in the amount of $3,400 is established by a charge against the current (2012) income tax provision.

Among the foregoing positive and negative factors to be considered, perhaps the most difficult to fully grasp is that of available income tax planning strategies. Since ASC 740 requires that all available evidence be assessed to determine the need for a valuation allowance, the matter of the cost of implementing those strategies is irrelevant. In fact, there is no limitation regarding strategies that may involve significant costs of implementation, although in computing the amount of valuation allowance needed, any costs of implementation must be netted against the benefits to be derived.