Understanding the Strategic Landscape into which Big Data Must Be Applied

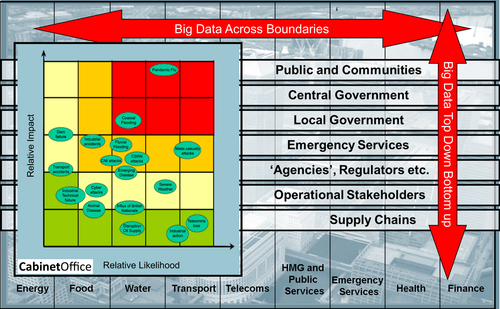

Emergencies and threats are continually evolving, leaving CI and communities vulnerable to attacks, hazards, and threats that can disrupt critical systems. More than ever, our CI and communities depend on technologies and information exchange across both physical and virtual supply chains. These are rapidly changing, borderless, and often unpredictable.

All aspects of our CI and of the communities in which we live are affected by continuously shifting environments; the security and resilience of our CI and communities require the development of more efficient and effective mechanisms, processes, and guidelines that mirror and counter these changes in the strategic landscape, to protect and make more resilient those things on which we depend and the way of life to which our communities and society have become accustomed.

CI functions with the support of large, complex, widely distributed, and mutually supportive supply chains and networks. Such systems are intimately linked to the economic and social well-being and security of the communities in which they are located and whom they serve, and with the wider societal reliance for such essential services as food, utilities, transport, and finance.

They include not only infrastructure but also networks and supply chains, both physical and virtual, that support the delivery of an essential product or service.

Future threats and hazards, particularly those caused by the impacts of climate change, have the potential to disable CI sites to the same if not greater degree as a terrorist attack or insider threat. The impact of severe weather such as flooding or heavy snow may disrupt the operation of sites directly or indirectly through supply chain and transport disruption. In addition, the tendency to elevate terrorism as the main threat rather than to consider the full range of hazards from which modern society is at risk results in site-specific plans that assume damage will be the result of acts targeted directly at the critical facility—either a physical attack or an insider threat—rather than a side effect of a wider natural hazard or other non-terrorism–related event affecting either the geographical location in which the CI is located or the interconnected supply chains on which it depends.

The individual assets, services, and supply chains that make up the CI will, in their various forms, sit either directly within a community or straddle and impact multiple communities depending on the sector or the services provided.

As with the CI and its interdependent supply chains, where once geographic boundaries were the only means of describing a community, in our modern interconnected world, a community may and indeed often does extend beyond recognized boundaries, embracing those of like-minded interests or dispositions through shared values and concerns wherever they may be, locally, regionally, nationally, or internationally.

These communities are not static, homogeneous entities, easily described with their entire essential needs catered for by those responsible and then set in stone and left. A community is fluid and constantly changes, as do its needs, across and between the many different layers from which the whole is made. A community has discrete communities within it and further ones within those. A community and its behavior and interactions both within itself and with other communities, and with its dependent relationship with the CI, can more easily be described as an ecosystem.

The following Wikipedia definition of an ecosystem (

Wikipedia, 2014) is useful to allow us to picture and compare the value of using such a description:

An ecosystem is a community of living organisms (plants, animals and microbes – read people) in conjunction with the non-living components of their environment (things like air, water and mineral soil—read CI and essential services), interacting as a system). These components are regarded as linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. As ecosystems are defined by the network of interactions among organisms, and between organisms and their environment, they can be of any size but usually encompass specific, limited spaces although some scientists say that the entire planet is an ecosystem. (For the CI, communities and the essential services and supply chain upon which they rely, these nutrient cycles, energy flows and network of interactions represent our modern interconnected and interdependent world).

Ecosystems are controlled both by external and internal factors. External factors such as climate, the parent material which forms the soil and topography, control the overall structure of an ecosystem and the way things work within it, but are not themselves influenced by the ecosystem. Ecosystems are dynamic entities—invariably, they are subject to periodic disturbances and are in the process of recovering from some past disturbance. (For the CI and communities, read man made, natural or malicious events).

As our reliance on the networked world increases unabated, modern society will become ever more complex, ever more interconnected, and ever more dependent on essential technology and services. We are no longer aware of the origin of these critical dependencies; nor do we exert any control or influence over them. In the developed world, there is an ever-downward pressure on cost and need for efficiency in both the public and private sectors. This is making supply chains more complex, increasing their fragmentation and interdependency and making those who depend on them, citizens and their community ecosystems, more fragile and less resilient to shock.

The security and resilience of the CI and of communities are key challenges for nations and those responsible. A collaborative and shared approach among all affected stakeholders, whether public, private, community, or voluntary sector and across artificial and man-made borders and boundaries, is now recognized as the most effective means by which to enhance security and resilience to counter this

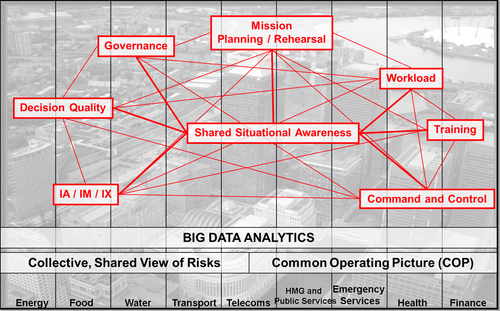

complexity. The application of Big Data to improve the security and resilience of the CI and related communities could provide a step change in helping to achieve this. However, this can happen only if those responsible for our protection from harm and promotion of well-being become, along with the application of the Big Data itself, as interconnected and interoperable as the CI system of systems and the community ecosystems are themselves.

Alongside the need to understand the structure and makeup of the CI system of systems and community ecosystems before Big Data can be meaningfully applied, it is equally critical to understand the issues and challenges facing those responsible for security and resilience planning, preparedness, response, and recovery: the resilience practitioners, emergency responders, CI operators, and policy makers. Their issues and challenges are intrinsically linked to the ability to enhance the security and resilience of the CI and communities.

It is accepted thinking that the ability of nation states, and indeed of broader institutions such as the European Union, to increase resilience to crisis and disasters cannot be achieved in isolation; it requires all stakeholders, including emergency responders, government, communities, regulators, infrastructure operators, media, and business, to work together. CI and security sectors need to understand the context and relationship of their roles and responsibilities within this interconnected system. This complex “system” of stakeholders and sectors can result in duplication of effort, missed opportunities, and security and resilience gaps, especially where each stakeholder organization has a starting point of viewing risk through its own individual perspective. When greater collaboration and a more collective effort are required, this tends to drive an insular approach when actually it is the opposite that is required.

Where they do consider this “wider system,” and the nuclear industry is particularly good in this respect, other factors such as a lack of internal or regulatory integration or a holistic approach to understanding the human elements as they relate to governance, shared risks, and threats and policy undermine this wider view.

An example is recent events in Japan after the devastating earthquake and tsunami that damaged the nuclear power plant at Fukushima Dai-ichi. The natural disaster damaged not only the reactors, but also the primary and secondary power supplies meant to prevent contamination, and the road network, which prevented timely support from reaching the site quickly.

In this instance, safety and security in the nuclear industry have traditionally been regulated and managed in isolation. Safety management has been the responsibility of operators, engineers, safety managers, and scientists, whereas security tends to be the responsibility of a separate function frequently led by ex-military and police personnel with different professional backgrounds and competencies. Similarly, regulators for safety and security are traditionally separate organizations.

The complex, interconnected nature of safety, security, and emergency management requires convergence; without it, serious gaps in capability and response will persist. Although this approach would not have prevented the devastation at Fukushima, had the regulators of safety and security been integrated into mainstream organizational management and development, because it is neither efficient nor effective to consider nuclear safety cases, security vulnerability assessments, and financial and reputational risk separately, certainly some of the consequences at Fukushima could have been mitigated, as the work of the World Institute of Nuclear Security clearly articulates in their International Best Practice Guides.

Much of the debate on CI security and resilience centers on the critical national infrastructure, i.e., the people, assets, and infrastructure essential to a country’s stability and prosperity. However, what

seems evident is that much of what is critical to a nation sits within local communities, often with a strong influence over their economic and social well-being. Disruption to that infrastructure, whether man-made or natural, not only has an impact across a country, but can seriously undermine communities, some of which may already be fragile economically or socially.

CI operators and those in authority charged with keeping the community safe recognize the integral role that CI and its operators have in the local communities upon which they have an effect. In this respect, the term “critical local infrastructure” might be more meaningful because it highlights the importance of involving local people in aspects of emergency preparedness planning and training regarding elements of the CI based in their communities.

A more collective approach and ownership of large-scale, collective risk is essential to meet twenty first–century challenges. The challenges facing a fragmented community not only affect operational effectiveness—in the worst case putting lives at risk—they also result in inefficiencies and duplications that are hard to identify and hard to improve or remove. Natural disasters, industrial accidents, and deliberate attacks do not recognize geographic or organizational borders and the weakness at these interchanges might themselves present weaknesses and vulnerabilities that can be exploited. Risks that appear to be nobody’s responsibility have the potential to affect everyone.

Therefore, it should also be clear that the requirement to make appropriate risk assessments needs to be a coherent and integrated process involving all sectors, agencies, and organizations, and which includes the ability to prioritize the risks identified. Such an approach would, for example, enable a collective assessment to be made not only of which risks are greatest, but which risks might be acceptable and which are not, with procurement within and between organizations made, or at least discussed on this basis.

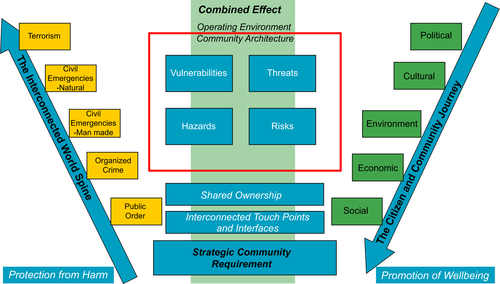

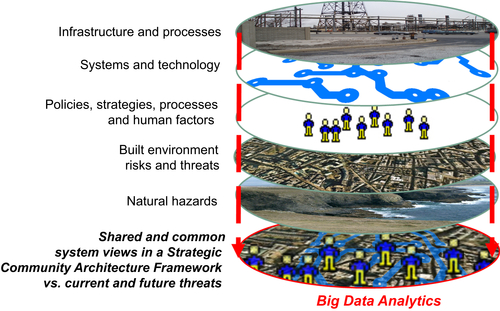

The need for a collective effort to achieve the combined effect between all of the stakeholders in a community, both the consumers and providers (i.e., citizens, CI, and responders), across the spectrum of “harm and well-being”, has never been more apparent. Achieving a common scalable and transferable means to better understand, plan for, and counter these complex interdependencies and their inherent vulnerabilities to the consequences of cascading effects, whatever their origin or cause, has never been more critical.

Despite their varying social, cultural, geographic, and ethnic differences citizens and their communities have shared needs in their desire for safety, security, and well-being. The CI, too, despite its operational, geographic, and networked diversity, has a shared need across its different sectors and supply chains for a greater, more enhanced view of the risks and threats it faces, especially from the hidden, unseen interdependencies, and how these can be managed in a more coherent, cohesive, effective, and efficient way.

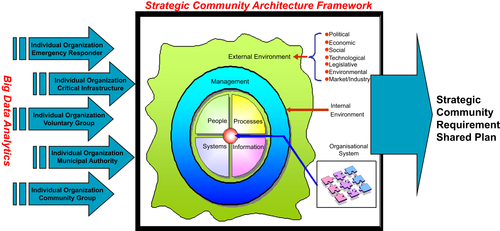

This shared means, whatever the size, makeup, and location of a community, and from whichever touch point a citizen has engagement, can be described as its strategic community requirement (SCR). Without such a means to achieve this combined effect, our modern society and the millions of individual communities from which it is made can only become less resilient to shocks, whether man-made, natural, or malicious; less cohesive to increasing social tensions; and increasingly unable to provide the quality of life expectations of citizens that our politicians so espouse.

Despite the structural complexity of both community ecosystems and CI system of systems, with the inherent difficulty of understanding how they coexist and interact, with their shared needs for safety, security, resilience, and well-being, this SCR provides commonality and overarching consistency; giving an opportunity to support greater visibility and enhanced cohesion and coherence to improve resilience across the many different moving parts and players.

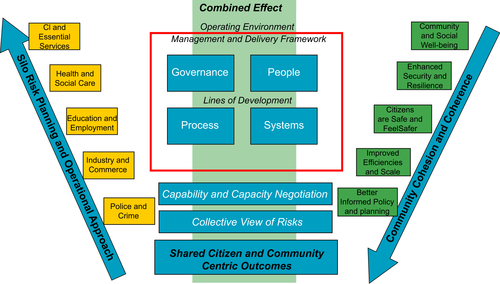

Use of an overarching architecture to achieve this would enable a single, unified view of the world from which a shared, collective approach to enhancing the security and resilience of the CI and

communities can be carried out under a common SCR framework. Within this framework, the application of Big Data by end users can be meaningfully undertaken to maximize and achieve the benefits sought.