67. How to Develop a Richer Voice

Be Your Own Echo Chamber

Ever since Adam and Eve, the difference between men and women has been discussed and debated ad infinitum. In voice, however, the difference is indisputably clear: The larynx, or vocal cords, the principal component of the human voice, is smaller in females than in males; and so, just as a guitar’s shorter and thinner strings produce a higher-pitched musical tone, a woman’s shorter and thinner vocal cords—as well as those of a small man—produce a lighter, higher-pitched sound.

And so do the vocal cords of a teenager. There’s the rub: The squeaky quality of an adolescent’s voice is a mark of their immaturity, and so women and small men with thin, high-pitched voices are unfairly saddled with the same perception—a career-limiting handicap.

In an early scene in The Iron Lady, a biopic of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Meryl Streep, who portrays Lady Thatcher, is told by her political consultants that her screechy voice lacks gravitas. The next scene is a montage of Ms. Streep/Thatcher being coached by a voice teacher who tries to get her to drop her tone by raising and lowering her extended arms.

This method is effective for pumping air from the lungs and adding volume to the voice, but it does little to the tone of the voice. The basis of high-pitched sound is not the air flow coming from the lungs, but from the vocal cords, which are situated above the lungs, and so the correct way to enrich the voice is to work from the larynx up by creating resonance.

Resonance

The word “resonance” combines the prefix “re-,” meaning “repeat,” and “sonance,” meaning “sound.” Repeat sound. An echo is a repetition of sound. Think of the times you’ve stood deep in a cave or high on a mountain overlooking a valley and said “Hello!” and then heard your own “Hello!” bounce back or resound in a deep boom.

The echo of your voice contained overtones and undertones that made your original “Hello!” sound deeper and richer. If you could add overtones and undertones whenever you speak you would develop a deeper and richer version of your own voice. You can create an echo with the mechanism of your own body without having to enter a cave, stand on a mountaintop, or haul around an amplification system.

Let’s analyze the elements of the mountain echo: Your voice originated in your larynx, and then traveled across the open space of the cave or the valley. The sound then struck the walls of the cave or the sides of the valley and bounced back with renewed energy. The bounces are resonance, the reverberations that add the overtones and undertones that enrich the original sound.

The elements of that process were:

• Your voice

• The open space of the cave or the valley

• The walls of the cave or the sides of the valley

Or put another way:

• A source

• An open chamber

• A hard surface

You can incorporate those elements into your normal, everyday speaking voice because:

• Your larynx is the source of your voice.

• You have open chambers in your own body.

• You have hard surfaces in your own body.

Please note my restatement that the larynx is the source of your voice. Many schools of thought about vocal production focus on the role of the chest, the lungs, and the diaphragm—and for the voice coach in The Iron Lady, the arms—but they are not the source of voice. All those components do is generate a silent column of air that only becomes voice when it passes through the vocal cords. Sound does not occur until there is vibration.

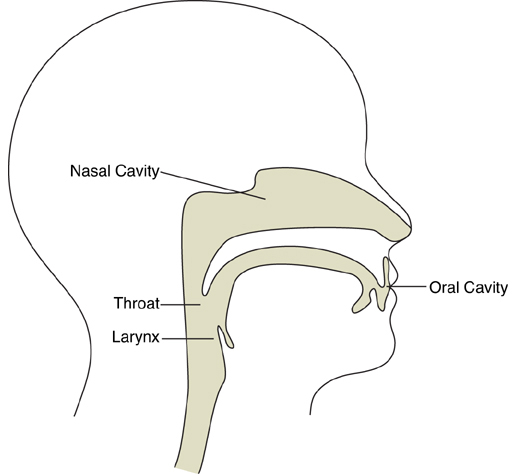

Granted your chest, lungs, and diaphragm are open chambers with hard surfaces, but they are positioned below your larynx, and so there is no sound to resonate. If you look above the larynx, in Figure 67.1, you will see three open chambers or cavities, each of them is lined with hard tissue that provides a surface to bounce the vibrations that your larynx produces, to resonate the sound of your voice.

Figure 67.1. The pharyngeal, oral, and nasal cavities

• Your throat, known as the pharynx, or the pharyngeal cavity

• Your mouth, the oral cavity

• Your sinuses, the nasal cavity

As you speak, the vibrating air column of your voice passes through these three chambers anyway, but resonance is not a given. To create resonance you have to optimize the bounces by opening the chambers wider. The larger the chamber—the deeper the cave, the steeper the valley—the better the bounce, the greater the boom.

Be Your Own Echo Chamber

The vibrations produced by the larynx are expressed in two types of sounds: vowels and consonants. Vowels are usually identified as “a,” “e,” “i,” “o,” and “u,” and consonants as every other letter in the alphabet. Actually, there are more than a dozen and a half different vowel sounds and countless consonant sounds. Rather than detail each one, however, let me simplify the definitions.

Consonants are sounds that are impeded by the actions of the lips, teeth, and tongue, while all vowel sounds are unimpeded or open sounds that are varied only by the shape of the mouth and the position of the jaw. Every vowel sound is the equivalent of your “Hello” on the mountain top, ready to reverberate into overtones and undertones.

Vowel sounds occur in every word we speak, even in Slavic languages, where some words do not have a single letter representing a vowel, but every word has a vowel sound. Therefore, you can use every vowel sound to add resonance to your every word.

Since every vowel sound travels through your throat and your mouth, these cavities can become your echo chambers for resonance. To incorporate the other available chamber, the nasal cavity, we turn to three other sounds: “m,” “n,” and “ng.” Although these three are consonants—because they are impeded—they occur so frequently in our language, they provide you with an additional echo chamber and an additional opportunity to add resonance to your voice.

To develop nasal resonance:

Hum “mmm.” Consciously focus on pushing the sound into your nose. Prolong the sound. Feel the vibrations in your nose and across your cheekbones.

Hum “nnn.” Consciously focus on pushing the sound into your nose. Prolong the sound. Feel the vibrations in your nose and across your cheekbones.

Hum “ng,” as in the end of “going.” Consciously focus on pushing the sound into your nose. Prolong the sound. Feel the vibrations in your nose and across your cheekbones.

You have just experienced nasal resonance in isolation. Now say “many men marching.” Concentrate on exaggerating the “m,” “n,” and “ng” sounds in each word.

Now say “moon beams bring evening dreams.” Concentrate on exaggerating the “m,” “n,” and “ng” sounds.

Now say “a strong new nation is going in motion.” Concentrate on exaggerating the “m,” “n,” and “ng” sounds.

You have just experienced nasal resonance in controlled word strings.

Now pick up a newspaper or magazine and read a paragraph aloud. Concentrate on exaggerating each “m,” “n,” and “ng” sound as it occurs in random words.

Practice these exercises daily until you find your own comfort level, the point at which your movements feel less exaggerated, but your voice sounds richer. The time it takes to reach that level will vary by person and by the time and diligence each person applies.

When you feel comfortable, try to speak with resonance in select private situations: with a family member, a friend, or a co-worker. Little by little, as you gain more facility, you can begin to try to resonate in more open social settings. Do it in small increments. Walk before you run. Wait until you have attained mastery to try your new skill in a mission-critical presentation or speech. The operative word is progressively.

To summarize, you now have a five-step process to develop nasal resonance:

1. Isolated exercises

2. Controlled word strings

3. Random exercises

4. Conversation

5. Presentation or speech

Steps 4 and 5 depend on your own rate of progress. Now let’s apply the first three steps to oral and pharyngeal resonance.

To develop oral resonance:

Say “ow,” as in “how.” Consciously focus on rounding your lips. Prolong the sound. Feel the reverberations in the front your mouth.

Say “ah,” as in “as.” Consciously focus on dropping your jaw and placing the sound in the front of your mouth. Prolong the sound. Feel the reverberations in the front of your mouth.

You have just experienced oral resonance in isolation.

Now say “how now brown cow.” Concentrate on exaggerating each vowel sound and feeling it reverberate in the front of your mouth.

Now say “so flow can grow slowly.” Concentrate on exaggerating each vowel sound and feeling it reverberate in the front of your mouth.

Now say “as an afternoon advances.” Concentrate on exaggerating each vowel sound and feeling it reverberate in the front of your mouth.

You have just experienced oral resonance in controlled word strings.

Now pick up a newspaper or magazine and read a paragraph aloud. Concentrate on exaggerating each “ow” and “ah” sound as it occurs in random words.

Now move on progressively to steps 4 and 5.

To develop pharyngeal resonance:

Say “on.” Consciously focus on opening your throat and dropping your jaw. Prolong the sound. Feel the reverberations in your throat.

Say “oh.” Consciously focus on opening your throat and dropping your jaw. Prolong the sound. Feel the reverberations in your throat.

You have just experienced pharyngeal resonance in isolation.

Now say “on an old island.” Concentrate on exaggerating each vowel sound and feeling it reverberate in your throat.

Now say “a hot shot on the top.” Concentrate on exaggerating each vowel sound and feeling it reverberate in your throat.

Now say “he ought to be caught and taught.” Concentrate on exaggerating each vowel sound and feeling it reverberate in your throat.

You have just experienced pharyngeal resonance in controlled word strings.

Now pick up a newspaper or magazine and read a paragraph aloud. Concentrate on exaggerating each “on” and “oh” sound as it occurs in random words.

Now move on progressively to steps 4 and 5.

Your goal is to get the point where none of these techniques is a conscious effort; the point at which every word you speak gets channeled into its own chamber where it caroms around into overtones and undertones.

The result will be a rich, resonant voice that commands attention and gives you the power advantage.

The Pause Bonus

In Chapters 47 and 53, respectively, “Sounds of Silence” and “Foreign Films,” you read about how pausing at the ends of your phrases gives your audience time to absorb your words. Pausing can also help to improve the quality of your voice.

If you speak rapidly, in a steady flat line string of words with few pauses, your vocal cords will vibrate rapidly and gain momentum. Rapid vibrations produce a high frequency or high-pitched sound.

If instead you break your word strings into logical bites—phrases—and punctuate them with pauses, you bring your vocal cords to a full stop at the end of each phrase. When you restart your next phrase, your vocal cords will start vibrating from a still position and take a short while to gain momentum. During this interval, your vocal cords will vibrate more slowly. Lower frequency produces a lower pitch.

Obey the traffic rules of good speech: Come to a full stop at the end of your phrases and pause.

Combine the lower pitch created by the pause and the overtones and undertones created by pharyngeal, oral, and nasal resonance, and you will speak with the voice of authority.