C h a p t e r 10

Module 2—The Creative

Process: Developing Options

Module 2 is recommended for all decision-making programs—half-day, full-day, and two-day—except for half-day programs for managers and supervisors, which use only modules 1 and 9. Module 2 introduces the subjects of creativity and risk in decision making.

Training Objectives

After completing module 2, the participants should be able to

- explain the importance of creativity in decision making

- clarify the goal of a decision

- develop or identify viable options from which to choose

- calculate the degree of risk related to a decision.

Module 2 Time

Module 2 Time

- Approximately 1 hour

| Introduction, welcome, and review | 5 minutes |

| PowerPoint presentation | 30 minutes |

| Worksheet exercise and discussion | 20 minutes |

| Wrap-up, learning check, and preview | 5 minutes |

Note: This includes time for a quick review at the start and a learning check at the end.

Materials

- Attendance list

- Pencils, pens, and paper for each participant

- Whiteboard or flipchart and markers

- Name tags or name tents for each participant

- Worksheet 10–1: Decision Analysis Sheet

- Computer, screen, and projector for displaying PowerPoint slides; alternatively, overhead projector and overhead transparencies

- PowerPoint slide program (slides 10–1 through 10–14)

- This chapter for reference or detailed facilitator notes

- Optional: music, coffee or other refreshments.

Module Preparation

Arrive ahead of time to greet the participants and make sure materials are available and laid out appropriately for the way you want to run the class.

Sample Agenda

| 0:00 | Welcome class. |

| Have slide 10–1 up on the screen as participants arrive; go to slide 10–2 as you begin. | |

| Preview the agenda (the objectives) for this session. Ask for questions or concerns. | |

| Use slide 10–3 to review the previous module. | |

| 0:05 | PPT Presentation. |

| Begin with slide 10–4 and proceed through slide 10–10. | |

| 0:35 | Worksheets. |

| Distribute Worksheet 10–1 (Decision Analysis Sheet) | |

| Show slide 10–11 as the participants work on the worksheet. Show slide 10–12 as work continues. | |

| Move among participants to keep them on task. | |

| Have participants discuss the answers with others. | |

| 0:55 | Wrap-up. |

| Use slide 10–13 to review the objectives with participants. | |

| Ask for questions from participants. | |

| Check learning—questions can be oral or printed (see below). | |

| Show slide 10–14. Dismiss the class. |

Trainer’s Notes

![]() 8:00 a.m. Welcome participants (5 minutes).

8:00 a.m. Welcome participants (5 minutes).

Show slide 10–1 as participants arrive.

Take care of housekeeping items.

![]() 8:05 a.m. Creativity in Decision Making (10 minutes).

8:05 a.m. Creativity in Decision Making (10 minutes).

Show slide 10–2 and preview the module topics.

Show slide 10–3 and briefly review module 1.

Depending on how long it has been since the module was presented, you may skip this step. If you do use slide 10–3, you can say that module 1 covered seven steps in the decision-making process. This session will focus on Step 4, developing lists of options from which to choose. This is the “inductive” or creative part of decision making, also thought of as the “right brain” part, because that’s where it happens.

Show slide 10–4. Say the word creating. Note that the word implies some higher power. It is the process by which new or different things and ideas develop. Creating is something that most of us feel inadequately prepared to do. We don’t have that higher power, that extra skill, that unique insight that allows us to exclaim “aha!” as a light bulb magically appears above our heads.

Or do we? Look around at the people society considers creative: artists, advertising writers, inventors, journalists, and others.

Thomas Edison was much admired for his dogged determination in the face of thousands of failures to reach his few, albeit important successes. He even claimed that, “Success is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.”

Can you and I learn to be creative? Many books and articles on the subject are available, but the short answer is “Yes.” People are creative either because they have learned to be or because they somehow avoided developing or being hampered by blocks to creativity, some of which society presents to us. Note that the next module will deal with overcoming the blocks that get in the way of creativity.

Show slide 10–5.

If you think about it, you are already creative. Creativity does not require artistic talent or great skill or even above-average intelligence.

Think about your dreams. They are usually unstructured. Much of the time our creativity is unstructured, but, oddly enough, bringing in structure can help us to increase the creativity.

In terms of decision making, the first thing that must happen is to clarify what is expected from the decision.

8:15 a.m. The Goal of the Decision (10 minutes).

Show slide 10–6. Regardless of the specifics, what we’re dealing with here is a relatively simple idea: What do you want to happen? You must define the desired outcome of a decision before you can build a plan to make it happen. A cliché about decision making warns us: “If you don’t know where you’re going, you’ll never know if you’ve arrived.” Therefore, an important part of decision making is to establish your goals.

We usually get into making a decision because we either have an opportunity or a problem. If it’s a problem, the way we know that the problem exists is that we see its effects.

Note: Insert an example here, preferably a real-life example involving the organization itself.

At this stage in the decision-making process, you should put down in writing the related information you see as “facts.” Putting the facts on paper helps to clarify your understanding of the problem or opportunity. The facts need to be in writing to keep them clear and specific in the decision makers’ minds. Otherwise, the issue may become something of an “amorphous blob.”

Frequently, we may find that what we thought were accurate “facts” change as we get more information on the issue. Yes, that does mean the facts were probably wrong in the original assessment. Don’t waste time justifying why the facts changed; just move on. Simply restate the “facts” to reflect the new information. After all, if the complete information had been available in the first place, most likely there would be no problem to solve or decision to make.

A good way to handle this step of the decision-making process is to make several short lists. Two of these lists should be “facts” about:

- What is true regarding the situation at this point?

- What is not true regarding the situation at this point?

You may need some other lists, too. For example, let’s say the decision is what to do about standards not being met. In that case, another list should specify these facts. For example:

If standards were being met before, what changed? Listing facts is important because we often mistake one issue for another or believe that symptoms are really causes. Listing facts is an essential prelude to identifying the real goal.

Because the top goal isn’t always obvious, the manager may have to make several tries before being able to state what the goal really is.

Using cause-and-effect logic will help here (we’ll cover that in detail in module 5). But we usually start with the effect, that is, what’s not happening that should be happening (or vice versa). The effect (the deviation from what we want) is the problem that we must solve.

So, after listing the facts, we must test reality: If any of the facts or answers to questions are inconsistent with the undesirable effect (the deviation or issue at hand), then either we don’t have the real issue defined yet or the “fact” is wrong. To find out where we went wrong, we have to backtrack to the root cause of this effect and see if it is the issue. We have to keep looking for a prior, more basic, issue that, if resolved, will eliminate the current undesirable effect.

Once the goal—eliminating the root cause of the problem—is determined, move on to developing your choices for solving the problem.

8:25 a.m. The Difference Between Cause and Effect (5 minutes).

Show slide 10–7. How can a person not understand the issue? Let’s say a manager is quite concerned that the work in his or her area is not being accomplished. The manager may know for a fact that high absenteeism exists in the department. From that fact, he or she has decided that high absenteeism is the cause of the problem. However, absenteeism may only be a symptom of other, deeper issues.

People may be absent because they know there aren’t enough parts to do the job, and that if they come to work they’ll just sit around or be sent home. Or they may be absent because the area is so dusty that they’re getting sick. In either case, the absenteeism isn’t the cause, it’s only a symptom of a larger issue.

If the managers start out with the wrong assumption, they’ll have to backtrack to find the real issue. They should list “high absenteeism” as a fact, nothing more. When they begin to determine the available options, it will be important to know about the absenteeism, but some other facts will also be needed. Note: Insert a real-life example here.

8:30 a.m. Developing Choices (5 minutes).

Show slide 10–8. Because this slide was part of the previous module, discuss it here only as a refresher. Remember the basics about developing your choices: Always consider all options before you gather information about them, and realize that you will never be able to consider every possible option.

How many options are enough? It depends on the nature of the decision. We’ll look closely at this issue later in the program and develop a variety of ways to create a broader and more effective list of options. For now, though, let’s say that four to 12 options are adequate for most decisions.

Show slide 10–9: Where to Get Ideas. Ideas are all around you; they come from other people, your own imagination and dreams, books you read, catalogs, movies, the Internet, nature, things that happen to you, and so on. Where you find them, of course, depends on what kind of a decision you’re trying to make. Module 5 in this training will suggest a number of techniques for improving your creativity. For now, however, we’ll move on to consider the amount of risk people are willing to take as they make decisions.

8:35 a.m. Risk in Decisions (5 minutes).

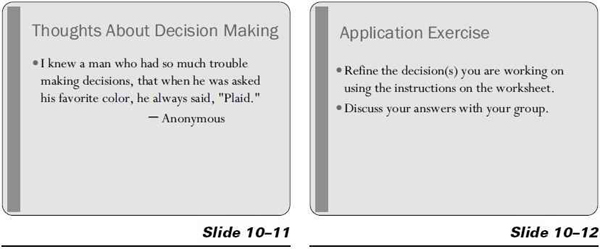

Show slide 10–10. This is an introduction to the part risk plays in decision making. If you are delivering all of the training modules, you will cover risk more fully in module 7.

We know from personal experience and observing others that people vary in the amount of risk they will take. We will leave to the behavioral scientists the reasons behind the phenomenon of risk taking. But we do know that decision making is influenced by such things as personality, the consequences of loss, the benefits of gain, group pressure, and many other things, even including the way in which the risk is stated.

Some people, called risk averters will take lower risks than indicated by the probabilities, whereas others, called gamblers will take greater risks. It might seem logical that if a person is given a decision with a 75 percent probability of one choice being the correct one, it would be chosen. This is not necessarily true, however, because there is a 25 percent chance of the decision being wrong. Some people will avoid even small risks, especially if the penalty for being wrong is severe.

As shown by the darker line in the graph on slide 10–10, most people will take some risk when the commitment is low, but will become conservative as the stakes increase. You might be willing to bet $1 at 10:1 to win a payoff of $5. When it’s a $100 bet for $500 at the same odds, though, most of us are more reluctant. It’s not the odds (they’re both 10 to one against you) or the payoff (both are five to one if you win), but the size of the commitment. We can afford to lose the $1, but not the $100.

Probability (shown on the vertical axis of the chart) is an important concept in the analysis of risk. We all hear weather reports saying that the “probability of rain is 60 percent.” What does this really mean? Does it mean that of the five meteorologists in the office, three think it will rain? Maybe.

The higher the risk, then, the more information we will probably want to collect to help ensure that our decision is correct.

Formulas exist in management science that can help determine the value of additional information. A simplified way of dealing with the question of how much information you’ll try to obtain is to ask, “What will be the cost of additional information (in time, money, or other resources)?” And to also ask, “What is the risk of deciding without it?” Sometimes those answers can be quantified, but often they can’t. So, seeking more information becomes a judgment call. If the risk is low and the additional information is expensive or time consuming to obtain, odds are that it won’t be worth it. If the risk is high and the additional information can be obtained easily, then go ahead and get it.

Remember, research into this issue shows that the threat of losses has a more significant effect on decisions than the expectation of gains.

8:40 a.m. Thoughts About Decision Making (15 minutes).

Show slide 10–11. Distribute Worksheet 10–1 (Decision Analysis Sheet).

The question is: Do you think the person described in the slide is a risk averter?

The question is: Do you think the person described in the slide is a risk averter?

Allow participants time to work on the worksheet.

Show slide 10–12. Ask participants to discuss the answers with each other.

Show slide 10–12. Ask participants to discuss the answers with each other.

8:55 a.m. Module 2 Summary (5 minutes).

Show slide 10–13. Review the module 2 objectives with participants and ask for questions. Use the learning check questions below to finish the class.

LEARNING CHECK QUESTIONS

LEARNING CHECK QUESTIONS

You can use the learning check questions and answers in oral or printed form.

Discussion Question

- What influences the amount of risk an individual will take when making a decision?

Answer: It’s complicated, but it starts with the individual’s personality and is adjusted by the importance of the decision and the consequences of being wrong.

Multiple Choice Questions

- Creativity is

a. Directly related to intelligence

b. Directly related to artistic ability

c. Requires a great amount of skill and practice

d. All of the above (answer)

e. None of the above - Creativity is

a. A natural activity in most children

b. Often limited by society and culture

c. Generally associated with the right side of the brain

d. All of the above (answer)

e. None of the above - People vary in their tolerance of risk. Someone who is unlikely to bet, even on a nearly sure thing, would be called a

a. Right-brained thinker

b. Risk averter (answer)

c. Gambler

d. Left-brained thinker

9:00 a.m. Thank You for Your Attention.

Show slide 10–14. Edit this slide to include appropriate information about your class. Dismiss the class.

Worksheet 10–1

Restate the decision(s) you were working with in the previous module.

What do you want to happen as a result of the decision? (Be specific.)

What do you know to be true about the situation?

What do you know to be not true?

What has changed, if anything?

Information Required

List at least four things you need or want to know to be able to make this decision:

- _____________________ ( )

- _____________________ ( )

- _____________________ ( )

- _____________________ ( )

- _____________________ ( )

- _____________________ ( )

In the parentheses, order them by importance to the quality of the decision. How much risk is involved in this decision, and how did you determine that?

© 2010 Decision-Making Training, American Society for Training & Development