In This Chapter

Creating a photo set

Classifying your photos

Preparing photo sets to sell in galleries or shops

Everyone likes collecting stuff (well, most everyone). Just visit any museum, and you'll find a collection of something. In fact, art museums call a series of related works collections! As an art photographer, you can become a de facto mini-curator, presenting your own custom collections that collectors will covet. (Kind of circular, isn't it?)

Remember that every photo tells a story. As a photographer, you are the storyteller — or in the case of photojournalism, the reporter. Use a photo set — a collection of related photos — as a marketing tool for your work and to tell stories. The common themes are endless, from color extravaganzas to a common subject to timelines. Perhaps you want to show a progression of events, like how quickly a newborn transforms to a toddler, or a bridge being built. You can also use a photo set to capture a series of related items or emotions, like a set that shows the different rides of an amusement park or a rainbow of young people in love.

Although you can shoot with a planned photo set in mind, don't overlook the opportunity to harvest a photo set from the images you already have in your collection — the story that you can eventually tell isn't always obvious while you are photographing dissimilar things. Sometimes the connecting theme appears later as a serendipitous surprise.

And don't forget the positive business aspects of selling photo sets: Offering a sequence of photographs is good business because many times people will buy the whole set instead of one — thus, you are building a product whereby people buy in multiples.

Selling a story using your photographs can encompass more than just your image. It can include the history of your community with documentation of its recent or historical development.

If you're a bit lost at first when designing a photo set — or need help keeping your creative focus on track — here's a very simple but effective tool you can use: a storyboard. Think of the basic panel progression technique used in comic book drawing or scripting a movie or TV show. A storyboard is nothing more than a progression of scenes, usually sequential (although your set doesn't have to follow a timeline). Your storyboard is your map. A sample storyboard of a sequence of shots in a grocery store is shown in Figure BC1-1.

Note

When you photograph any scene, keep photo sets in mind — shoot long, medium length, and close up. Keep these concepts in mind as you put together a batch of art into a set.

Identify the types of shots you want to use for your photo set.

For example, lay out a story using an establishing shot, medium shots, and close-ups.

Beginning: This is the establishing shot that tells you where you are — kind of like the setting of a novel. An establishing shot is usually a long shot: That is, it has great depth of field and is clear throughout. (For more on depth of field, see Chapter 5.)

Tip

A landscape photo can be an excellent establishing shot. In the movies or on television, this kind of shot often opens the show.

Middle: This is a medium length shot, used to pique the viewer's curiosity. It should show some detail to give the viewer knowledge of the character's surroundings.

End: This is a close-up that announces the finale and also gives closure. On a dSLR, I like to use portrait mode and shoot with a traditional blurred background. For more on portrait mode, see Chapter 5.

Decide how many photos to include in the set.

How many depends on the number the gallery or store can fit in their space. You have to size up where you want to sell to determine how many photos you're going to put out there. One thing is for sure, though — if you have a popular and abundant photo set, keep updating them with new images. I have nearly 1000 mid-century motel sign images that I constantly update and upgrade, so people can collect as many as they want.

Decide whether to include text and how you will do that.

Adding text to your artwork has become much more common since the 1960s when artists such as Andy Warhol experimented with using messages about social behavior with his images. More about that in the "Text" section, later in this chapter.

Following your storyboard guideline, your shots fall into place, as in Figure BC1-2.

Two main types of storyboard are

Sequential: A series of images that tell a story. An example of sequential actions shots could be a boy on a playground swinging and then jumping off, as in Figure BC1-5 in the upcoming section, "Timelines."

Topical: A series of images that explains how you do something. Mundane as this might seem, take an everyday activity such as brushing your teeth and make a photo set out of it by showing the pictures of the steps to do it.

You don't have to follow the path of a storyboard, though. Think about how other people present collections, remembering times when you've visited a museum or a gallery. You move through a museum or gallery following a preset direction, eyeing pieces that are displayed in a deliberate fashion by the curators and owners. These folks pick the images and purposely decide where to place a piece in terms of where patrons will look and what they'll see when they stop to look. Simply, you follow a set — a collection.

To see how some exhibits are curated at museums, see www.metmuseum.org or visit some local galleries.

You make the choices to define a collection of images and how to group them, just as a curator does. You are, in fact, a curator of your own exhibit. And as curator, you have many options for defining a set:

Related subject

Theme/emotion

Color

Black and white (B&W)

Timelines

Panoramas

Composition

Patterns

Media

Note

Your digital camera photo software can display photos on your computer screen so that you can see them within a matrix that lets you zoom in and out. Review your images regularly. This can give you a sense of where you want to go in terms of subject matter. Any of these photo set groupings can spark your imagination to help you name your photo sets.

Note

Having a name for a set enables you to communicate the idea of your project to store/gallery owners and museum curators both online and in person. You can also develop a pitch — that is, a quick one-sentence or -paragraph description of what your set contains.

Tip

Keep your end audience in mind. For example, an industrial-looking photo series is appropriate for an office.

Similar subjects are natural in a collection. For example, if you like to photograph collies, a collection of shots showing them at work, play, and sleep is perfect for those Lassie lovers. Speaking of collies, don't forget to look for twists of differences among similar things. For example, consider a collection of shots of border collies — true, they're all the same thing, but because all border collies are marked differently, you have a same-but-different collection. The same premise holds true when photographing a collection of different puppy breeds — you're showcasing puppies (great "aahh" factor), but they're all different — or even old-time radios, as shown in Figure BC1-3.

Tip

Two or more of anything in each photo of a set adds dimension. It also gives you a natural name for your set for a show.

And don't forget that collection of photographs of pricey objets d'art is a great way for a collector — and potential buyer of your photos — to afford adding to their collection of their fancy. For more on shooting objets d'art, see Chapter 4. Photographs of historical items sell.

Using all B&W shots can really show your stuff as an art photographer. You can highlight common subject matter, shadows, lighting, or patterns. For more on B&W photography, see Chapter 9.

Grouping a photo set by color is a natural eye-catcher. You can group like items by colors (a set of different purple-toned flowers) or show a progression of colors (a four-shot, per-season series of the same nature scene). Figure BC1-4 shows a photo set of purple flowers, selected for their color.

Repeating compositional elements creates cohesion in a collection. You can shoot a series of any similar geometric shape, such as lines, circles, or triangles.

Use a sequential series of shots to umbrella an event. This could be as dramatic as a horse race or as everyday as a child on a swing (see Figure BC1-5). See the earlier section, "Crafting a Photo Set from a Storyboard," for how to use a storyboard as a map to create a timeline.

Repeating pattern elements is also an easy way to create a collection. Look for checkerboards (think patios and tile floors), swirls (an eddy of water, a drain, or a giant lollipop), and woven items (close-ups of baskets, knit or crocheted items, or wicker furniture).

Pattern repetition also gives motion to your photos, letting the eye follow similar objects, each that tell a story. Any repeating pattern from geometric to free forms stimulates the brain to continue the pattern it sees well beyond the photograph itself.

Note

Keep the background pattern in mind when shooting for a photo set. See pitfalls to avoid in the upcoming section on polishing your images in an image editing program.

The final print is what it's all about. Presenting your set on a similar type of media — photographic paper, vinyl, fabric — ties them together. Or (being the artsy kind of person you are) take the same shot and present it on different types of media for a together-but-contrasting look.

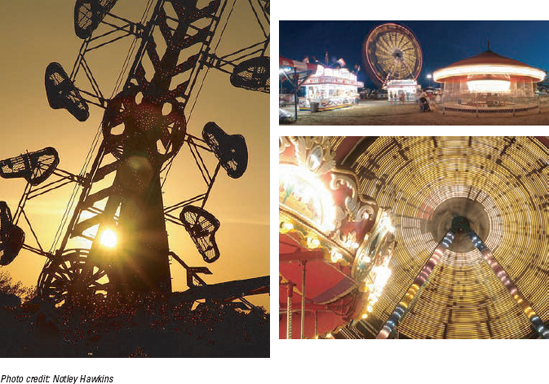

A common theme (like birthday parties for your budding child) or emotion (like older couples holding hands) is also a natural collection. You can build a theme on anything, tailoring it for niche stores and boutiques where you live. For example, in the Midwest, you might be able to market a photo set of fair or carnival scenes (see Figure BC1-6).

Time passes, and people and places change. Keeping track of it all can be overwhelming. Not very many people keep track of what was where, when in your community. Sure, there's probably a historical society somewhere, but they deal with really old things.

You can showcase such a historical perspective by creating a photo set with a reverse timeline, using shots of people or architecture from the past of the same subject. Search your archives to find interesting shots that you've taken (or people have taken of you) 5, 10, 15, 20, and even 50 years ago. If the subject still exists, take a photo of it as it appears today. You become a historian of sorts.

Note

Be a curator for your own images. Keep your files organized by folders or within a photo cataloging application like iPhoto or Adobe Album. I file mine in folders using categories such as architecture, animals, landscapes, people, sculpture, objets d'art, and signs. Remember, too, that such programs enable you to assign keywords (words and phrases added to the image files) and perhaps categories. Later you can search by keyword to find all the images to which you have assigned to it. Keywords and categories are wonderful for not just organizing, but for locating specific images — even if you don't remember the file name, the date taken, or even the specific content.

Of course, knowing which images to keep and which to throw away is the trick. Toss weak shots while they're in your camera. If you're not sure, keep them until you can look at them on your computer. Clean out your images every week: Don't let your sorting grow to the point where there are so many images you don't know what to do. Spend 15 minutes each day cleaning them out so that the task isn't so overwhelming that you give up.

Note

You can't find the images you want if you don't know where they are. Keeping images that fit into categories helps when you search for the one you want.

After you have a set of photos, you need to prepare them for presentation and sale. Factor in size, printing/media, judicious use of text, framing/matting, and pricing.

Size is an important consideration when crafting a photo set. Choose appropriate print sizes and offer choices. For example, you might choose a smaller print size (say a series of 3″ × 5″s) for objets d'art. For a panoramic cut series, consider a strong horizontal print size — say, 8″ × 4″. The repeated shapes bring cohesion.

Of course, you could vary the sizes but retain similar shapes, which makes for interesting combinations when displaying. For example, use two rectangles of different sizes and two squares, as shown in Figure BC1-7.

When thinking about size to make the images in your photo set, remember to keep your buyer in mind. Larger images cost more to produce, and thus are pricier.

Before you fire up the old printer, you'll want to make sure that each photo for your set is consistent in tone and contrast, and that the background in each is not distracting. (This is something to look out for as you shoot, too, so that you have less tweaking to do in this later stage.)

People do look at backgrounds — you have to be careful that they don't interfere with your primary objects in your foregrounds. A background that complements your computer desktop computer can't be so evasive as to interrupt your view of the icons on your screen. The same thing goes for photography.

You can copy and paste thousands of backgrounds into your photo in Photoshop so that you tweak the individual photos in a set to present them with a unified look.

Tip

Web sites such as http://market.renderosity.com sell high-resolution studio background images for about $8 per image.

For more on high-quality printing, see Chapter 17. For more on tweaking your image for contrast and tone, see Chapter 12.

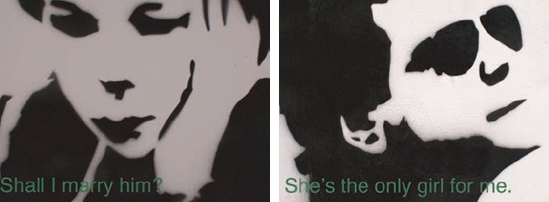

You can photograph any object and make up a story about it and include it with the image as shown in the set. Artist Roy Lichtenstein created an enormously popular series of comic book-like characters — colorful characters made out of small dots each saying something in text. For more about adding text to an image in Photoshop, see Bonus Chapter 2.

Figure BC1-8 shows a similar concept using portraits that were originally whole body figures stenciled on a wall in Europe.

Your framing choice adds to the cohesion of your photo set. Classic sleek black framing lends strength to architectural shots; aged barnwood is appropriate for rustic shots; brightly painted colors are suitable for a child's theme. Likewise, matting can add an air of sophistication or whimsy. See Chapter 18 for great sources on your framing and matting needs.