Making age-old creative decisions in your photography

Identifying interesting photography subjects

Creating photos that intrigue viewers

Turning old family photos into art

Transforming your life experiences into digital art

No doubt about it: Photographs are a personal thing. After all, a photograph is a way for you to show the world how you see something — your perspective. In order for you to create art photos — you know, images with impact ... more than the average snapshot — you have three tasks ahead of you:

Define yourself as a photographer.

Define your audience.

Master your tools and hone your craft.

You have dozens of possibilities at your disposal to bridge that gap. First, you have to do a little introspection — investigate who you are. Then you move on to identify your audience. Peruse this chapter to help you identify yourself, choose subjects to express your creativity, and pinpoint those folks who would be interested in your art.

After you have those parts of the puzzle knocked out, you have to choose your subject matter. The world that you can catch on your camera is one very big place. From your immediate surroundings to your neighborhood, your town, your friends, your family, your state, your country, your travels ... the list is endless. You have tons of choices as subjects for your digital art photography.

Finally, read other chapters of this book to find help with the photography tools, rules, tricks, and tweaks to take your images from average to art.

Making art is one of the most rewarding activities that you can pursue because it's something you create yourself with your own personal touch. How personal you want to get is up to you. Some traditional photography artists have work displayed in modern art museums, brushing the edge in controversy. For example, Robert Mapplethorpe, in the 1980s, made headlines when he used the medium to reflect on the pain of his personal life.

The list of photographers who have taken a personal look at their lives is long, and there probably isn't one who didn't evaluate his or her life to come up with the subject matter for his photographs. To name but a few, look at the work of William Eggleston, Annie Leibovitz, David Hockney — and even moon-walker Neil Armstrong.

So if you're going to be an art photographer, should you hang out at cafés and smoke hand-rolled cigarettes? Well, not if you don't want to. (But if you see someone who's smoking a hand-rolled cigarette in a café and who looks amiable to having his picture taken, by all means ask him. That could be an art photo opportunity.)

Perhaps you have no interest in people or their interactions. This certainly doesn't mean that you can't be an art photographer. Take pictures of what appeals to you visually — like in Figure 4-1 — to help define yourself as a photographer. For example, perhaps you're drawn to color (think carnivals, marketplaces filled with rainbows of fruit, or fields exploding with poppies). Or maybe you're attracted to the shapes and forms of nature, such as winding streams, gnarled trees, and majestic peaks. You get the picture.

Note

To figure out what type of pictures you take the most, look at your pictures you've taken and sort them by categories. If you find that you take a lot of pictures of the same things — say, street scenes — you're on your way to finding a subject that you like (and learning about yourself as a photographer).

Many well-known photographers choose the streets of famous cities as the subjects of their work. If you find that you have a tendency to shoot a particular subject (like street scenes, as in Figure 4-2), then by all means, concentrate on that subject. The more you practice, the better you'll get at capturing and finding different ways to showcase your fave subjects. When you really know your subject, you can better find niche markets for your photos, too.

If you find yourself gravitating toward classical poses and subject matter, study what well-known artists through the ages chose for their subject matter.

Notice how the subject matter evolves from cave men drawings to religious figures and still lifes (as in Figure 4-3) to nature. The summary of the subject matter of the history of art ends with social commentary about the Great Depression. Art has progressed to modernity through many evolutions. What comes next is up to you. For more detailed information about the subject matter that classical artists have used throughout the ages, you can look at Art For Dummies, by Thomas Hoving (Wiley).

After you study the classical masters, take a look at some photographic masters at www.masters-of-photography.com. Works from all the biggies of photography are featured there. Check out Helen Levitt for some cool 1940s grafitti, Ansel Adams for the world's greatest landscapes, Diane Arbus for weird but wonderful people, and E. J. Bellocq for early 20th-century characters. Throughout this book, I reference more artists to help you interpret the masters' photos and refresh their ideas a bit so you refine your own photographic style.

Maybe you've heard the phrase, "Oh, he's a left-brained guy," or "She's right-brained." Having one part of your brain dominant over the other shouldn't stop you from taking good digital pictures. This cognitive tendency will, though, probably affect the type of subject matter you choose and the perspective that you choose. It could also affect how you take a picture. Consider right- and left-brained tendencies in terms of an art photographer.

If you're left-brained, you're

Logical: You can figure out patterns. You're good with numbers, problem solving, measuring, and data collecting.

Analytical: Given a set of circumstances, you can provide the answers. You like organization and specific details, preferring to know how things will turn out.

If you're right-brained, you're

Intuitive: You're ruled by gut feelings. You can delve into subjective thinking and make up stories.

Holistic: You accept randomness and use what's given to synthesize something. You like the creative process and can tackle more than two things at once.

If you're left-brained, you can assume the following:

Your photography is more ordered and shot more professionally, with more and better equipment. If you need a tripod, you'll get one. You take more time shooting. You have more posed shots and take the opportunity to use a planned lighting scheme.

Your photographs address technical issues before creative ones. You probably won't be the kind of photographer who shoots spontaneously. Figure 4-4 shows a posed photo, a nice photo that was planned and not spontaneous.

If you're right-brained, you can infer that your photography will be

Random: You'll "shoot from the hip," so to speak, taking pictures unexpectedly of whatever you want. Sure, you might plan some, but you realize that the creative moment is fleeting, especially if you don't take the time to compose your photo. Figure 4-5 a creative use of the environment — in this case, the ocean, to create a spontaneous and fun shot.

Creative: You'll seek and find the strange and unexpected and capture it quickly with your camera. Taking a walk with your camera strapped around your shoulder means that it won't stay there long. You seek out new ways to use your camera, taking pictures of nooks and crannies, close up with settings that you're not supposed to use.

So are you one or the other — or perhaps both? Could be. And more. With the special innate human ability that we have to learn new things, you can do things that you ordinarily wouldn't instinctively do. You can be a left-brained photographer using right-brained techniques if you train yourself, or just take the brain you have and specialize in the type of photography you want to pursue, be it randomly shooting pictures of what you want or planning for large-scale professional photo shoots.

Have you ever gazed at a series of pictures of someone and noticed that the person can look very different in each shot? A person can vary so much from one photograph to another that he might not even look like the same person. In a way, that's perspective, whether from the advent of time (cough, aging, as in Figure 4-6), mood, lighting, setting, angle, and so on. Perspective is everything: Changing its focus is the difference between a birthday bash in full swing or showing the remnants when it's over. The more you can personalize the perspective in your photos, the more you define yourself as an art photographer.

For more about the popularity of nostalgia photos and how to retouch them, see Chapter 12.

Note

To experiment with perspective, photograph something — anything — from close up, far away, from all different angles (as in Figure 4-7), and in different lighting situations.

After you get the standards under your belt — perhaps by visiting museums and checking out the masters — study the up-and-coming artists to see how they "twist" some of the rules. Then branch out on your own to give your viewers something unexpected.

You can take your photography a step further by including the unexpected in a portrait — for example, by including a close-up of a subject that's not human. For instance, instead of a human being, how about using something else — say, a mannequin? Figuring out how to take an art photo of a nontraditional subject is worth your while because viewers stop to look at art photos in which you add a little more than what they expect — as I've done in the portraits in Figure 4-8. (I guess you could call this trio a photo set; for more on those, see Bonus Chapter 1. And for more on capturing non-human subjects, see Chapter 7.)

Note

Statues and inanimate objects present an intriguing opportunity to present the unexpected to the viewer.

Note

One step further: Consider other take-what-you-already-know-and-add-a-little-more possibilities by throwing potential Did you know? questions at the viewers of your art photos. For example, many people think of coconuts as brown, but in their husks, they're green. And most coconuts in Florida are bright golden yellow as they ripen (as in Figure 4-9).

After you initially define yourself as a photographer, it's time to define your audience. Maybe your audience is just yourself; nothing wrong with that.

Perhaps, though, you're looking to turn an avocation into a vocation: that is, sell your photos. There are plenty of markets for art photos, from local stores and restaurants to home decorating outlets to stock photo houses to galleries to online venues to publications to.... Get the point? If you want to try to create marketable art photos, the horizon is wide open. However, you do need to figure out who will buy what. After all, folks at a tractor convention likely aren't interested in your photo collection of mannequins. And that focus is what defining your audience is all about.

So how to define your audience? Take these factors into consideration:

What type of art does your audience like? Portraits, landscapes, action (as in Figure 4-10)?

What type of art does your audience collect?

Does your audience have religious or political leanings?

Where will they purchase your art? Online? Shop?

What can they afford?

Keep in mind that a potential audience collects "things." Maybe they yen for pricey items, like vintage cars or delicate objets d'art, as in Figure 4-11. You can offer these folks an affordable way to add to their collection.

Your audience (or your taste) will dictate what you photograph and how you photograph it. So what should you shoot? How do you find interesting and compelling subject matter? Do you need to go on safari to exotic lands and hobnob with the jetsetters to find exciting and dramatic subjects? Nah. Start in your own backyard (which you probably know pretty well) and always keep your eyes open for the art that exists all around you.

Many people spend a significant part of their life in one area. Any area — rural, suburban, or urban — is a great place to take art photos. To find objects to include in your art photos, just take a look around. As a start, focus on the colors, the landscape, the art, the lifestyle, the sports, the architecture, the wildlife, the flora or where you live.

Through all your waking hours, you pass art, see art, and even make art. With a digital camera in hand, your life is art. Everywhere you look, it's there — colors, shapes, forms, people, places, things — all art, all the time.

Notice, too, that your locality (and those to which you travel) is kind of an independent and unique place on the world map, a place where unique things happen and where pictures of life and art go unnoticed most of the time. Figure 4-12 shows a local carnival. Carnival scenes are extremely popular both among the museum/gallery set and among buyers all over the world. They show both simple, colorful pleasures and sometimes-tawdry scenes with color playing tantamount roles in what amounts to plays of the old Technicolor days of film.

Think of your community as a place to find art objects for your photographs. Whether a big city or small town, art abounds — you just have to find it. In the art world is the concept of found art: namely, objects you find that you put in an artistic context. Pieces can include almost anything, such as the following:

Nuts and bolts

Rusted signs

The plastic holder from a six-pack of cans

A stick with perfect symmetry

A fossil

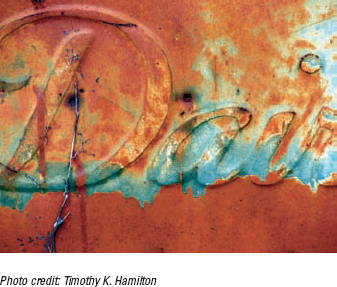

Figure 4-13, an old sign weathered by time, is a perfect example of an artful found shot. As an artist, check out and shoot different close-ups within the context of your found art — nooks and crannies and even the critters within — just as sculptors do for their works using found art.

Another way to determine your subject matter is to research what sells. This has two advantages:

You know what subjects are popular.

You can tell whether you've found a hole — that is, a niche market that no one else is filling. Figure 4-14 shows a motel sign from the middle of the last century, one of a series that I've produced for a niche market of digital art photography. There are many takers for the pop-filled, so-called Googie images. Photos of Googie architecture sell. Googie landmarks are everywhere, built in the 1960s, featuring swoops, geometrical figures of steel, and sometimes neon.

If you're unsure what to photograph that's saleable, you can do some searching on the Internet to help you. There are many ways to do this and millions of sites to choose from.

Here are two ways to get started:

In your search engine, type in "stock photo" (include the quotes) as keywords to find what type of images they show.

Stock photos are the images that editors of magazines and newspapers buy to print in their publications. The images are usually listed by category, so that you can do a search for the type of image you like by typing a word in the search of the stock photo Internet site. Searching a stock house's offerings shows you what images are saleable and what kinds of images you might offer the stock house for sale.

Go to your Internet search engine and type the name of your community and the word "art" in the image search. What better way to find images of your community to take a step further than seeing what's out there to begin with?

Above all, your presentation must be stellar and unique. After all, you want your photographs to stand out, be memorable, and be enjoyed for years. That's what presentation is all about. This is the culmination of your craft: your subject, your perspective, composition, image finessing, printing, and framing. Here are some ways to make your art stand above the common herd.

Digital photography is an evolving art form. A ground swell of interest in the subject is brewing, but much more can happen as the medium develops. You can do much to develop the art form of digital photography:

Move beyond traditional photography techniques applied to the digital realm. Digital photographers can develop new ways to work with the medium before and while shooting and composing (as in my crazy zoom in Figure 4-15). You can also manipulate your shot in an image processing program like Photoshop as well as during printing. This book covers lots of techniques to help you express yourself through your photographs; the more adventurous of you will want to home in on Chapters 11, 13, 14, and 20.

Collaborate with other artists to produce new works of art. Existing paintings often can be photographed with new results when they are printed digitally. One example is a photograph of a painting on velvet. Photographs of this type of work actually turn out better than the painting itself. (Maybe it has to do with the fact that velvet collects dust easily.) The portrait on velvet in Figure 4-16 is almost 50 years old; picked up at a garage sale and photographed, this image was digitally upgraded with great results.

Warning

You must be careful, however, not to commit copyright infringement. Rather than be sorry, consult with an attorney about this important issue.

Take a photograph that makes a statement. Many photographers choose to spotlight social issues, such as homelessness (as in Figure 4-17). These types of compelling photographs make their way into many art museums and high-end galleries. For more information about these types of issues as they're related to photojournalism, see Chapter 9.

Tip

Before using anyone's likeness, consult a publications lawyer to make sure you can use the image. Generally speaking, if the person or persons in your image are identifiable, you'll need to get signed model releases. You can read more about these in Chapter 7.

Use the knowledge and methods to make other art forms. And you can help your viewers identify other disciplines that might interest them. What better way to get your kids to look at their multiplication tables than to photograph them written by them on a piece of paper or off a black/whiteboard?

Target, Wal-Mart, Ikea, and similar stores all sell framed photos. Most are of an inferior quality compared with what a photographer can print out on his home computer and good-quality printer (say, Epson Stylus 2200 color inkjet). Your personal touch adds a little more to what the big-box stores are selling, making it a competitive, saleable product:

The road to good photo art has finally been paved for the consumer. Maybe the big-box outlets will catch on and sell the more artsy pieces, too, but a creative digital artist is likely to outpace the art sold that is mass-produced.

The digital artist can find the niche in subject matter for his community (as in Figure 4-18) that a big-box store probably wouldn't invest in. Subject matter for a big-box store is limited to that which is derivative: that is, tried and tested to not offend every person in every community in the country. They don't represent risk takers: That's left to the individual photographers and the museums, galleries, and smaller shops that display their work.

The digital artist can create images from photographs that he took, using equipment and processing tools and printers that he chooses. The big-box stores use the same materials pretty much nationwide.

Going up into the attic and tossing through your great-grandfather's WWII gear, old JFK memorabilia, and perhaps a depression glass collection wrapped in vintage 1940s The Kansas City Star newspaper sounds like a challenge ... maybe something you've been putting off for a long time. Don't miss the opportunity to search through all these wonderful treasures and photograph them before you toss them in a garage sale.

Whether what you find are prints or slides (a positive image, in photographic terms) or negatives or anonymous hand-drawn items that are about to fall apart, you have a treasure trove of photographic and restoration opportunities awaiting your creativity. Scan these precious images and work your magic with them, retouching them and reproducing them.

Warning

Again, just be careful about infringing on a copyright inherently or obviously (signed) belonging to another photographer or creator. Consult with an attorney to learn more about copyright and copyright infringement — to make sure you don't infringe upon someone else's work and also to protect your own.

Here's an example of how you can preserve and repurpose an old image, bringing it into this millennium. Figure 4-19 shows an older image before and after sharpening it and then applying the Photoshop Colored Pencil filter. The digital photo on top in the figure was taken with a digital camera from an original slide (a very old one at that, too) set on a light table. Being of an artistic mind, I decided to sharpen it and run it through a Photoshop filter to create my own version of the turn of the last century.

Note

If you think it's not worth scanning a bunch of old family photos, think again. If you have a scanner — and especially a negative scanner — you can transform the old stuff in that dusty attic into a collection that spells a-r-t.

Here are four reasons to go up in the attic, bring down those photos, and digitize them, either scanning the prints or scanning the negatives and/or positives:

Enlargements of these types of photos are being sold in the trendy LA stores for lots of money. No kidding, prints of women and men in wild '40s, '50s, and '60s outfits are fetching hundreds of dollars.

Looking at an old photo's patina onscreen or in print is like taking a time machine back in time. These treasures need hardly any manipulation in Photoshop because they're amazing aged, just as they are, like the picture shown in Figure 4.20.

You discover how your older relatives (and the dead ones) looked when they were young. Geez, you find out that you look like them! (Check out such a timeline in Figure 4-6).) You're also saving the photos for future generations to see. Remember that photos on photo paper don't last forever.

You can add to your existing photo collection. Fill your photo folders with old and new and hang them on the wall together. For example, combine the new street scene photos with older ones.

Warning

Be wary when repurposing vintage photos. You might need permission, or at least a model release, to reuse an image of someone. Even if that person is deceased, you might have to contact their heirs for permission. See a copyright attorney for the exact rule about this and let him know what type of photo you have as well as what you plan to do with it. Also, see Chapter 7 for more about this issue. Also, practice with your image editing program (like Photoshop) to iron out scuffs and creases in old photos (see Chapter 12). Above all, bring something new to the image: You could create a photo set, tweak the color, use it in a montage — after all, if you're just copying an old photo, that doesn't make you a photographer.