Chapter 9. Deciding Where and How to Play

In the public speaking business, it is often said that a good presentation should answer three questions: What? So what? And now what? So far in this book, we have addressed the first two questions by introducing the Global Brain and its awesome power to turbocharge innovation, and by describing the four models of network-centric innovation. But we are still left with the third, and perhaps, the most important question—now what do we do? How should your company tap into the Global Brain? What model should it use? And how can you prepare your organization to embrace a network-centric innovation strategy? In this chapter, we offer a practical roadmap for companies and managers to identify and pursue opportunities for network-centric innovation that best match the context of the company and its business environment.

In the process of researching this book, we interviewed a senior manager at a large, Midwest-based technology firm who was responsible for leading his company’s collaborative innovation initiatives. During our conversation, the manager remarked that in the last two years or so, the company had been dabbling with “open” innovation initiatives. However, he was not satisfied with the progress they had made. He felt that a lot of energy and investment had been expended on these efforts with little to show in terms of tangible outcomes.

The problem was not a lack of commitment from senior management, R&D, or the product development organization. Rather, he felt that the problem lay in the lack of a coherent approach to identify, evaluate, and pursue externally-focused innovation opportunities. Compounding the issue was the fact that the company participates in a wide range of markets and has several thousand products spread across many business units. Faced with a wide array of opportunities, the executive felt that the company was unclear about what opportunities and relationships it should focus on, and how it should pursue promising opportunities.

This concern is echoed by managers in many large companies we have studied. We respond to this concern by offering a three-step approach to addressing the question of where and how a company should tap into the Global Brain through a network-centric innovation strategy:

- We look at how a company can scope its network-centric innovation initiatives and determine the most appropriate opportunities.

- We show how the company should prepare itself in terms of organizational capabilities and resources to pursue those specific opportunities.

- We highlight best practices that it can adopt for implementing its network-centric innovation strategy.

In this chapter, we focus on the first step by providing guidelines for managers to evaluate the different types of opportunities based on industry/market factors and to select the opportunities that best leverage the firm’s resources and capabilities as well as align with the firm’s overall innovation agenda.

Positioning Your Firm in the Innovation Landscape

The discussion in the previous four chapters illustrated that different models in the landscape of network-centric innovation have different implications for a participating firm—implications for the nature of the innovation roles, innovation capabilities, innovation outcomes, and value appropriation. If there are “different roles for different folks,” how should a company answer the seemingly simple but important question, “Where does my company fit in the network-centric innovation landscape?” (see Figure 9.1)

Figure 9.1. Positioning your firm in the network-centric innovation landscape

The first step in answering this question requires analyzing the industry and market characteristics for the firm and identifying the quadrant in the network-centric innovation landscape that is most appropriate for the firm’s context. For large multibusiness companies like P&G, DuPont, GE, IBM, and Unilever, this analysis might need to be conducted at the Strategic Business Unit (SBU) level, because the industry and market context is likely to be quite different across the SBUs. For example, at GE, the GE Healthcare business has a very different business context from GE NBC Universal or GE Money.

The second step is to analyze the nature of the innovation contribution that the company can make and the specific role it can play in that part of the network-centric innovation landscape. This analysis has to take into consideration the requirements of the innovation role as well as the unique resources and capabilities that the company can bring to the innovation context.

We start with the first step.

Deciding on the Most Suitable Model

The firm’s innovation context plays a key role in determining which model of network-centric innovation is most appropriate. Three broad sets of questions frame the context:

• How well defined is the innovation space? Are the innovation goals clearly articulated? Does the innovation define a new architecture or extend/enhance an existing architecture? How visible are the market opportunities? How well tied are the innovation goals and the architecture with those market opportunities?

• What is the nature of the knowledge and capabilities demanded by the innovation? Do innovation projects involve highly specialized or advanced domain knowledge? What is the extent of knowledge integration required? What are the capabilities needed for participating in the innovation activities? How widely distributed (or available) are these capabilities?

• How well established are the mechanisms for appropriating value from the innovation? Will the innovation require establishing radically new value appropriation systems? Does the innovation context allow a mix of “open” and “closed” IP rights systems to coexist? Is it possible to deploy a diverse set of incentives to appeal to different types of contributors?

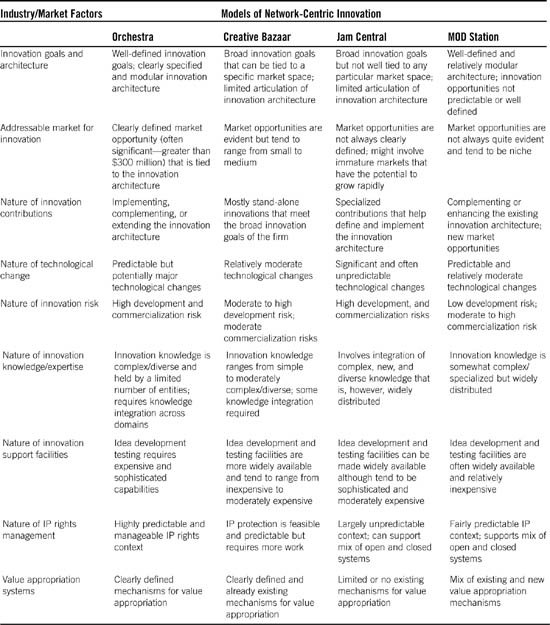

Table 9.1 captures the important industry and market conditions that reflect the preceding issues and shape the choice of the different network-centric innovation models. Based on these factors, we now describe the typical context that best suits each of the four models.

Table 9.1. Contingencies for Models of Network-Centric Innovation

First, consider a context when there is a clearly defined innovation architecture or technology platform that is well tied to a market opportunity with established mechanisms for value appropriation. As we have seen from the examples of Boeing and Salesforce.com, this context is best suited to the Orchestra model, particularly if the knowledge needed for implementing the architecture is highly specialized and held by a few entities or if partners’ capabilities are important to enhance the reach and richness of the ecosystem. Further, if the technological or market risk in the innovation project is relatively high, it is important to pool and share risk with a network of partners. Markets that show these characteristics include semiconductors, software, computer hardware, biotechnology, networking equipment, consumer electronics, and so on; in each of these sectors are several examples of the Orchestra model.

In contrast, even if the innovation architecture is clearly defined, if the existing market opportunities have already been exploited and new market opportunities are not very clear, then the context suggests the use of the MOD Station model of network-centric innovation. The case of Sun’s OpenSPARC Initiative is illustrative of this model. The MOD Station model works particularly well if the innovation knowledge is diffused or widely distributed and the innovation context demands a mix of open and closed IP rights management systems. In such a context, the full or partial unlocking of the innovation architecture to facilitate more “open” and community-based innovation pursuits can uncover new market opportunities for applying or extending the innovation architecture—opportunities that had never been recognized or targeted by the firm that devised the architecture. And as the examples of the computer game industry and the Web-based information services industry suggested, as long as the right mix of incentives (and IP rights systems) are created, such community-led innovation can benefit all the members of the network, including the firm that created the architecture or platform.

In other situations, the innovation architecture or the specific innovation outcomes are not defined but the market opportunities are visible and/or well articulated. If such a context is also marked by innovation expertise and facilities that are not too complex and are rather widely distributed, then the Creative Bazaar model becomes relevant. As we saw from the various examples in Chapter 6, “The Creative Bazaar Model,” several markets in the consumer products industry (for example, office supplies, home care, and so on) are typical of such innovation contexts. Individual inventors can think of innovative product ideas that align well with the broad market goals and objectives articulated and communicated by large firms. Further, it is important to utilize an existing infrastructure for commercializing the innovation, which can only be provided by a dominant firm in the network.

An additional interesting issue here relates to the nature of the market opportunity. Our research suggests that the typical size of the target market associated with the Creative Bazaar context tends to be relatively modest. Indeed, if the market opportunity is relatively big, then it might pique the interest of a large firm, which would pursue it aggressively. The Creative Bazaar context works well when the market opportunity is diverse and rich in detail—thereby calling for very innovative (even if simple) solutions.

Finally, consider a context where the innovation architecture is not very well defined and neither are the specific market opportunities. Instead, only the broad contours of the innovation domain might be evident. In this context, there is fairly high development risk as well as market risk. Such a context becomes ripe for the Jam Central model of network-centric innovation. Examples of such contexts include new and emerging technological areas (for example, biotechnology, nanotechnology, renewable energy, and so on) or previously uncharted areas of existing domains (for example, software, drug discovery, and so on).

In such a context, if the innovation knowledge or expertise is also widely distributed, then it might lead to the formation of a network of innovators who have a shared interest in that innovation domain but do not have any immediate focus on value appropriation. The specific innovation goals and architecture will then emerge from the interactions of these network members, as was the case in the Tropical Disease Initiative discussed in Chapter 7, “The Jam Central Model.” The need to continue to attract and maintain the creative energy of the members requires a more “open” governance system, one that ensures every member’s ability to voice and influence the innovation proceedings. In addition, the greater the ease with which open IP policies can be deployed in the innovation context, the greater will be the appeal of the community. Further, a combination of factors—including lack of clarity on immediate market potential, longer innovation incubation time, and higher extent of innovation risk—all contribute to corporate entities assuming a sponsoring role rather than a more active role in the innovation process.

The identification of the most appropriate model related to an innovation context is only one part of the solution. The second part is to identify the most appropriate role that the company can play in that innovation context.

Deciding on the Most Suitable Innovation Role

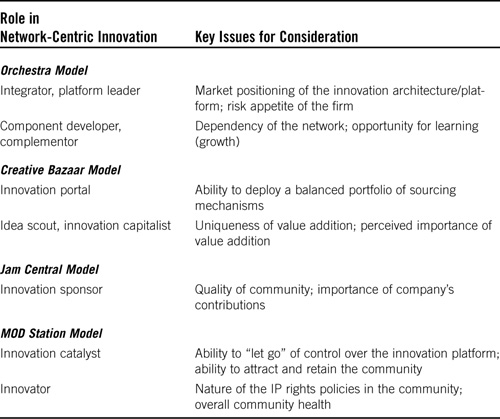

In earlier chapters, during our discussion of the four models of network-centric innovation, we had identified several innovation roles that firms can play. Table 9.2 lists these different roles. Firms choosing to play one of these roles should carefully examine the key underlying issues and conditions that would determine the appropriateness of that role or opportunity.

Table 9.2. Roles in Network-Centric Innovation

Participating in the Orchestra Model

The two types of roles that firms can play in the Orchestra model are the role of the integrator or platform leader and the role of a component developer or complementor.

Integrator or Platform Leader

As our two case studies—Boeing and Salesforce.com—showed, firms wanting to play the role of an architect in the Orchestra model need to own an innovation architecture (or platform) that has significant appeal to a wide range of potential partners who can contribute in developing the innovation components or complementary products and services. In addition to this requirement, two key issues determine whether the firm can play the role of an integrator or platform leader.

The first issue relates to the addressable market for the innovation platform or architecture. Is the market opportunity defined by the innovation architecture large or broad enough to support the network? We saw in the case of Boeing that the key initial consideration for the company was the ability to appeal to a large enough market—one that could support and justify the investments made and the risks assumed by Boeing’s partners. Similarly, the role of a platform leader will also be more successful if the innovation platform is relevant to diverse market contexts including niche markets. Consider IBM’s role as platform leader in its Power architecture network. While the platform’s original target market (for example, PCs and Workstations) is considerably large, the ability to find new niche markets is critical to sustain the appeal of the network to existing and new partners. For example, HCL Technologies, an India-based IT firm, recently started innovating on the Power architecture design—specifically, the PowerPC 405 and PowerPC 440 embedded microprocessor cores—to extend its application to wireless and consumer devices areas. Thus, a key consideration for a firm evaluating an opportunity to play the role of architect in an Orchestra model is the size of the addressable market.

The second issue relates to the firm’s own internal resources and risk appetite. Devising an innovation architecture (or platform) and building a network of partners around it takes considerable time and resources. Associated with such an investment is the considerable amount of innovation and market risk. In most cases, the platform will end up in a long and bitter battle of attrition with other platforms (for example, the current battle between the competing Blu-Ray and HD-DVD platforms for high-definition recorded video), and one or more of the platforms might end up getting marginalized (recall the Sony Betamax). Before electing to play the role of an integrator or a platform leader, a firm has to carefully evaluate whether it has the stomach to assume this level of risk. As our earlier example of Salesforce.com showed, a company can also gradually evolve into the role of a platform leader by committing more and more resources to build the network as the firm gains more success in establishing its own core products and technologies. Thus, the key considerations for a firm should be the amount of resources the firm can expend on building the innovation network and the extent of risk it is willing to assume.

Component Developer or Complementor

As an adapter in the Orchestra model—that is, a component developer or a complementor—a firm needs to contribute specialized innovation expertise or capabilities as well as bear its share of the risk associated with the innovation platform or architecture. Two considerations are important in evaluating such an opportunity.

The first issue relates to the nature of the connection between the firm’s specialized capability (that is, its contribution) and the network (or the innovation platform). On the one hand, the tighter the connection, the more likely that the firm will be a valuable network partner and that it can realize greater returns from its contributions. On the other hand, the tighter the connection, the greater the constraints the network will place on the firm’s ability to chart its own goals and strategies. Achieving a balance between these two forces is important. The questions to ask would be, “Can the firm ‘specialize’ its assets to meet the network’s goals without tying its own future with the success of that network?” “Are there opportunities for the firm to deploy the same set of assets to another network?” Or, “Will the opportunity to play the role of an adapter in a network move it away from other networks?” A firm has to consider these important issues before committing to a particular innovation platform or network.

Another issue that can dictate the choice of the adapter role is the learning potential associated with that role. By participating in the Orchestra model, a firm can acquire new capabilities or expertise (technological or market related) that might justify the overall risk it assumes in playing that role. For example, in the case of Boeing’s partners, some of the Japanese companies, including Kawasaki and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, have long-term plans of evolving into stand-alone aircraft manufacturers. They firmly believe that their experience and the technological expertise acquired from the 787 development program can help them achieve these future plans. Similarly, firms that develop complementary solutions on an innovation platform (for example, Microsoft’s .NET platform or Salesforce.com’s AppExchange platform) might discover that the potential to acquire new expertise from other network members would offset some of the risks associated with network failure. Thus, a key consideration in evaluating the adapter role, particularly for smaller firms, should be the potential to acquire additional expertise from their interactions with other network members.

Participating in the Creative Bazaar Model

We identified three types of roles in the Creative Bazaar model: innovation portal, inventor, and idea scout/innovation capitalist. Given that the role of the inventor is played largely by individuals (customers, amateur inventors, and so on), here we focus on the issues related to the other two roles.

Becoming an Innovation Portal

Firms can play the role of an innovation portal to ensure a rich and continual flow of innovative ideas for their internal product development pipelines. In evaluating the opportunity to become an innovation portal, the key consideration relates to the range of innovation sourcing mechanisms that the company will have access to in that particular industry/market. Specifically, will the company be able to employ a balanced portfolio of sourcing mechanisms that would enable the firm to manage the risks associated with entertaining and playing host to external ideas?

As we discussed in Chapter 6, the sourcing options at the left end of the Creative Bazaar continuum (for example, idea scout, patent broker) are attractive in industries and markets where amateur inventors can work by themselves with limited resources to come up with new product concepts. Thus, companies such as Dial, Staples, Sunbeam, Lifetime Brands, and Church & Dwight (represented by Firm A in Figure 9.2) with lots of small and diverse products might favor those mechanisms.

Figure 9.2. Toward a balanced innovation sourcing portfolio

On the other hand, the sourcing options at the right end of the continuum (for example, venture capitalist, external incubator, and so on) are more appropriate in innovation contexts that require considerable domain expertise and significant capital and time for development and market validation. Companies such as DuPont, 3M, and Kodak (represented by Firm B in the figure) who participate in science-based markets might rely more on those mechanisms.

Factors related to a firm’s particular market context are likely to imply a bias towards one set of sourcing mechanisms. However, there are downsides associated with relying exclusively on one set of mechanisms—accepting either too many risky ideas or too many expensive ideas. So it is advisable for a firm to balance its innovation sourcing approaches by complementing its favored approach with the other approaches on the continuum. This “move to the middle” might involve working with entities such as the innovation capitalist, who represents a compromise between the traditional two extremes of the continuum. Looking at Figure 9.2, Firm C and Firm D have a more balanced innovation sourcing strategy although their market and firm-specific factors might still imply maintaining an overall bias toward the left end and the right end, respectively. Going back to the example of DuPont, while it might find that buying companies is preferable in its traditional mature businesses, alternative approaches—like the use of innovation capitalists—might be used in emerging businesses like bio-based materials or electronics.

Thus, companies planning to play the role of an innovation portal should first evaluate their potential to employ a range of mechanisms so as to minimize the risk of unbalanced sourcing. In short, the greater the range of innovation sourcing options available in the particular industry/market, the better the opportunity for assuming the role of an innovation portal with acceptable risk.

Idea Scouts and Innovation Capitalists

Companies intending to play the role of an agent (product scout, patent broker, innovation capitalist, and so on) in the Creative Bazaar model need to decide the nature of their contribution (or innovation intermediation). In general, the greater the value addition a firm can bring to the innovation sourcing process, the higher the returns it can obtain from the client firm. However, two issues deserve careful consideration: First, what is the uniqueness of the value addition that the firm can bring to innovation sourcing? Second, how important is this value addition in the eyes of the client firm?

Consider the first issue. Does the firm have some unique access to inventor networks that it can leverage? Does the firm have specialized expertise or patented processes to filter innovative ideas or to conduct rapid initial market validation? For example, as we saw earlier, the Big Idea Group (BIG) cultivates its own network of inventors and also conducts unique roadshows that bring together inventors and a panel of experts to seek out good ideas. Or does the firm have unique capabilities to integrate different types of knowledge to advance or transform an innovative idea? Are there unique relationships with large client firms that the firm can bring to the sourcing process? For example, Ignite IP relies on its exclusive network of senior managers in large client firms to become aware of critical trends in technologies and markets. Absent such unique capabilities or relationships, it is unlikely that a firm can be anything more than a broker in the Creative Bazaar model with limited returns.

Typically, entities such as idea scouts and innovation capitalists focus on one or two specific industries or markets where they have deep domain advantage. It is important for such intermediaries to carefully consider the how much value addition the client firm will perceive in the contribution that they make. For example, in certain markets where numerous relatively minor innovative ideas need to be sorted out (for example, home improvement and self-help tools; toys), “idea filtering” might be perceived as valuable; on the other hand, in certain other markets characterized by fuzzy or unpredictable IP rights contexts, validating the IP rights of those ideas might be deemed more valuable. Thus, a firm should carefully consider the relative importance of the different value addition activities in innovation sourcing in a given market and decide the specific role that seems most promising.

Participating in the Jam Central Model

In the Jam Central model, the most likely role for a firm is that of the innovation sponsor. Given that the ideas emerge from the community, the role of the innovation steward will be carried out by those entities (mostly individuals) that provided the initial spark to the innovation context. Even the role of the innovator will largely be played by individual members of the community. As such, here we limit our focus to the appropriateness of the role of an innovation sponsor.

Innovation Sponsor

Firms don’t play the role of an innovation sponsor as an act of altruism or social service. Such decisions are always (and, we believe should rightly be) based on a sound business case.

Consider IBM. It has an important stake in the Open Source Software movement and actively pursues the role of an innovation sponsor in those initiatives. In an interview with Irving Wladawsky-Berger (IBM’s former vice president for technical strategy and innovation), he noted the rigor that IBM brings to this decision:

IBM takes Linux, Apache, and other such (Open Source) communities very seriously. For us, working with them is a no-nonsense business decision and we make them only after considerable analysis of the technology and market trends, the overall quality and commitment of the community, its licensing and governance, and the quality of its offerings. In our opinion, the key to such open innovation initiatives is the quality of the community, not whether you can have access to the source code of the software. And, if you don’t have a good community, then there is nothing in it for us to join. So we ask ourselves all these tough questions abut the community, its goals and objectives, its ways of organization before we make a commitment to support them.1

A “business decision” does not mean that a firm should play such a role only if there are direct or visible benefits. In many cases, such direct returns might not exist, at least in the short term. Instead, innovation sponsors need to focus on the indirect, and often long-term benefits that such a role might bring to the firm. For IBM, these benefits might include developing a favorable brand image and gaining influence in the Open Source Software community. In the case of the TDI, large pharmaceutical and biotech companies that are currently exploring a potential sponsoring role with TDI might consider the benefits of being exposed to trends and developments in drug discovery that are outside the scope of its traditional business units.

Another set of issues relate to the innovation outcomes. What are the types of expected innovation outcomes? How promising and significant are these expected outcomes? Do they have the potential to radically change existing markets? What types of IP rights mechanisms are likely to apply to such outputs?

Finally, it is also important to evaluate how the firm’s contributions to the innovation community are likely to be perceived. Are the inputs given by the firm as an innovation sponsor likely to be perceived as critical for the overall innovation? And how exactly will it help the community advance its innovation agenda?

The answers to the preceding questions can indicate the long-term success of the community agenda as well as the likely benefits the firm might potentially derive from supporting such an agenda. As such, it is important to give each of these issues careful consideration before committing resources to support the community-led innovation initiative.

Participating in the MOD Station Model

A firm can play primarily two types of roles in the MOD Station model: an innovation catalyst or an innovator. We start with the role of the innovation catalyst.

Innovation Catalyst

As an innovation catalyst, a firm contributes the innovation architecture or platform to initiate community-led innovation activities on it. Earlier, in Chapter 8, “The MOD (“MODification”) Station Model,” we had identified several incentives for a firm to make such a contribution. However, while the benefits to the firm might be evident, this does not necessarily mean that such a contribution will always spark the creative energy of the community. Indeed, the opportunity to play such a role is critically dependent on the nature of the innovation platform and as such many of the issues revolve around this dependency.

The first issue relates to the innovation potential associated with the platform. Unless the innovation platform is inherently perceived as valuable and also opens up a diverse set of innovative opportunities, it is unlikely that the firm would be able to attract a community of innovators around it. Thus, some of the issues for the firm are—how modular is the innovation platform? Is the modularity of the platform matched with the innovation interest of the community? Are the different innovation opportunities related to the platform visible? Are there specific market opportunities tied to these innovation possibilities?

The second issue relates to the incentives for the community to innovate. Will the firm be able to create a diverse set of incentives to attract and maintain the interest of the innovation community? Can the firm facilitate the application of a mix of IP rights mechanisms (for example, open and closed licensing schemes) that would cater to a wide range of community members—individuals as well as other entities?

Beyond the preceding questions is the issue of the firm’s own commitment to the initiative. As the example of Sun and its OpenSPARC initiative indicated, the process of building a community around such innovation architecture can often be slow and calls for continued commitment from the company. Further, the firm’s ability to gradually “let go” of control over the innovation platform and actively promote community-led governance will critically shape the continued participation of community members and thereby the success of the initiative. Sun took the step of incorporating lead members of the community into the first governance board that it helped to create. The success of OpenSPARC will be dependent on how well the community governance system works and how well the innovation opportunity offered by OpenSPARC can capture the imagination of the community members.

Thus, overall, a firm should carefully consider how it can open up the innovation platform to the community in a way that benefits everybody, including the firm.

Innovator

Now consider the role of the innovator. Although this role plays out in a community-based innovation forum, as we have seen from the different examples in Chapter 8, there are several ways to appropriate value from such innovation. As such, under certain conditions, it might be appropriate for a firm to play the role of an innovator in the MOD Station model. What are some of these contextual conditions?

First, and perhaps the most important, are the policies related to intellectual property rights. While some of the open licensing policies (for example, GPLv2) might preclude most profit-oriented development activities, other variations of the open licensing schemes might allow certain types of such activities, particularly on derivative products.

Another consideration relates to the overall size and health of the community. The larger and the more active the community, the greater the potential to sustain the platform over the long-term and the more likely there would be market interest for complementary solutions based on the platform. As such, a firm has to take a hard look at the quality of the community that the innovation catalyst has been able to attract around the platform and then decide how worthwhile it would be to play the role of the innovator in that community.

Table 9.3 captures the key issues that we have discussed so far regarding the different roles in the four models of network-centric innovation. As we mentioned earlier, these are only the more important ones; there might be other considerations unique to the firm that it will need to consider in evaluating the different opportunities.

Table 9.3. Considerations for the Roles in Network-Centric Innovation

Creating a Portfolio of Innovation Roles and Deciding the “Center of Gravity”

Sometimes, not only are there different roles for different folks, there may be different roles applicable within the same firm. Large companies like Unilever, DuPont, and IBM with diverse business units will typically find that there is more than one innovation role they can potentially pursue across their diverse innovation contexts. As such, it is important to think of the portfolio of roles that a large firm should assume as it formulates its network-centric strategy. Consider a few examples.

IBM plays the role of a platform leader in some of its traditional business areas, including systems and servers, semiconductors, and so on. The Power Architecture discussed earlier is a good example of this. IBM devised and articulated the platform and nurtured a network of partners to expand its reach and potential application areas. Even in many of its software product businesses (for example, middleware software platforms such as WebSphere, operating systems such as AIX, and so on), the company plays the role of a platform leader. On the other hand, more recently, the company has been playing the role of an innovation sponsor in some of the community-led innovation initiatives in the software industry, most particularly, the Linux community. The company has also started playing such a role in innovation communities in other domains—for example, in the biotechnology industry.

Similarly, consider P&G. In the consumer product business, the company follows the Creative Bazaar model and actively plays the role of an innovation portal. P&G partners with a diverse set of innovation agents including product scouts, eR&D marketplaces, and innovation capitalists to seek out innovative ideas that it can then bring inside to commercialize. On the other hand, in some of its other businesses—for example, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and so on—the company has followed the Orchestra model and played the role of an integrator. Specialized capabilities of partner firms are brought to bear in the development and commercialization of new products.

Sun Microsystems is an example of a firm that participates in both the Orchestra model and the MOD Station model. In much of its server business, Sun is a platform leader, developing and promoting proprietary technology platforms that form the basis for its products such as Sun Fire servers and Sun Ultra workstations. On the other hand, in recent years, the company has contributed some of its proprietary technology platforms to initiate community-led innovation initiatives. We described the OpenSPARC initiative earlier. Other similar initiatives including opening up the Java source code for community-based innovation have further expanded the company’s role as an innovation catalyst.

The preceding examples indicate the potential for companies to pursue a portfolio of roles in different parts of the network-centric innovation landscape. The nature of such a portfolio will be shaped by the industry/market characteristics of the different business units of the company. Further, it is also likely that one of those roles within the portfolio will assume dominance depending on the relative size and importance of the different business units. Such a dominant role indicates the location of the “center-of-gravity” of the firm’s network-centric innovation initiatives. Going back to the example of IBM, in spite of all the community-led innovation initiatives that the company has joined in recent years, its role as a platform leader is still dominant in its overall collaboration strategy. Similarly, it is evident that for P&G, the center of gravity lies in the Creative Bazaar model.

Why should you be interested in the “center of gravity” of a firm’s network-centric innovation strategy? As you will see in the next chapter, the nature of the resources and capabilities that a company needs to muster depends on where its center of gravity falls in the network-centric innovation landscape.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we showed how a firm can evaluate the different opportunities to tap into the Global Brain and identify the most appropriate role to play. After the firm has positioned itself in the network-centric innovation landscape, the next set of questions that arises is, “How can I prepare my organization to carry out such a role most effectively?” “What are the capabilities and resources that would be needed?” “What are some of the best practices that my firm should be aware of?” In the next chapter, we explore these issues.