Chapter 3. Current Accounts and Future Conquests: Existing and New Business Models

For years, industry watchers have been betting on which company would produce the first reliable, plug-in, electric-powered car. Most experts assumed it would be whichever auto manufacturer first developed a battery powerful enough to run its cars. Would it be General Motors and its Chevy Volt? Or maybe Tesla Motors’ Model S?

As it turns out, the pundits may have gotten things backwards. If all goes according to plan, battery-maker BYD could be the first company to deliver a mass-produced, electric-powered, plug-in vehicle, ahead of Detroit, Stuttgart, or Tokyo.

If you don’t know the company, open the back of your mobile phone. Chances are the battery powering the device was produced by BYD, a 15-year old company based in Shenzhen, China. Today, BYD is the leading supplier of batteries to Nokia, Samsung, and Motorola. Now it wants to be the leading supplier of power plants for a family of sedans, sub-compacts, and sports coupes that will bear its name. It’s no joke. Already BYD has attracted quite a following. Among those interested in the company: Warren Buffet, who plunked down more than $200 million to buy 10 percent of BYD in 2008.

To achieve its aims and provide a return for its backers, BYD has had to overcome vast challenges. It spent 10 years, for example, developing a battery that can power a car from 0 to 60 miles per hour in eight seconds and travel more than 100 miles when fully charged. And as early as 2003, it began acquiring manufacturing capacity and design expertise.

So why even try? Opportunity. The market for cars is on the cusp of an immense transition—from gas guzzlers to fuel-efficient and environmentally friendly vehicles. BYD, naturally, senses a once-in-a-lifetime chance to shake up the established world order. Newcomers, BYD leaders believe, have as good a shot at capturing the market. And what an opportunity it could be: According to various estimates, the worldwide market for electric vehicles could be as large as 10 million cars per year by 2016. That’s more than 12 percent of the global market for automobiles.1 “It’s almost hopeless for a latecomer like us to compete with GM and other established auto makers with a century of experience in gasoline engines,” says BYD’s wildly ambitious founder and chairman, Wang Chuanfu. “With electric vehicles, we’re all at the same starting line.”

To get to that starting line, Wang had to embrace a completely new business model to complement its existing model, something that is nearly impossible for most companies. To make the leap from invisible components to branded products, BYD had to develop a new workforce, create a consumer brand, ramp up government relations to engage national safety commissions, and create an entirely new supply chain. Any one of these can bury a company looking to augment its business model. And for good reason: These are extremely difficult challenges to overcome, all the more so in mature industries with high barriers to entry.

Despite the difficulty, some companies persevere. They do so because they believe new business models are the key to enormous value in the form of access to new markets, customers, investment capital, and profits.

This chapter highlights the benefits that can be derived from adopting new business models. It analyzes several companies that have successfully developed them, as well as a few that have tried and failed. It also analyzes the steps Cisco took to implement new business models and the lessons it learned along the way.

Let’s start by providing a glimpse into the world of those who have mastered the art of the “new business model” and those who have not. Take Disney, for example. Within the “Magic Kingdom” are theme parks, television networks, cruise ships, merchandising operations, and film studios, among other interests. Though they have different financial models, success metrics, and fundamentals, they nonetheless provide Disney an unrivaled footprint in entertainment.

Most companies never achieve anything close to this level of diversification. That includes some of the biggest and most successful companies on the planet. Many have tried and found it more difficult than previously thought. Take Google, for example.

Google has one of the most enviable business models—search-based advertising—of any company today. But its fortunes remain wholly dependent on that model, leaving it vulnerable to new competitors, market changes, or other challenges. Recognizing this, the company has tried to diversify its business for years. To help spur the development of new ideas, company leaders have gone so far as to encourage Google engineers to spend up to one day per week on open-ended projects that might lead to new business models or innovations. Several promising ideas have sprung from this approach, including the company’s Gmail messaging platform and its Google Apps software platform. Despite this, however, Google has yet to diversify its business model and thus remains dependent on its cash cow, which accounts for more than 95 percent of the company’s sales.

Given the unprecedented rise of Google in the global marketplace—it commands 71 percent of the search-based advertising market2—why should it bother with multiple business models? Because multiple business models provide a company a buffer against downturns in any one sector and an extra lift when times are good. They provide entry into adjacent markets and thus expand a company’s opportunity and preserve its longevity should one of its revenue streams come under threat from increased competition, regulatory changes, or even internal challenges. This is especially true of companies with broad portfolios of assets that can be combined to create new value.

IBM, for example, is weathering the 2008–2009 recession better than most tech giants because of this very reason. Its earnings actually increased while those of Dell and Intel fell by double digits. That’s because IBM began diversifying its business a decade before the recession crippled the global economy. Since 2000, for example, the company has purchased 40 software companies. It also expanded its services and consulting business with the 2002 acquisition of PriceWaterhouse Coopers Consulting. These acquisitions, along with ongoing structural changes, have significantly changed IBM’s revenue model. When customers buy from IBM today, they rarely pick from an a la carte menu. Instead, they buy solutions that integrate hardware, software, and services. Increasingly, they buy these solutions not as a single transaction, but as a long-term service annuity instead. This shields IBM from the capital spending cutbacks that tend to occur when markets turn sour.

As a result of the changes the company made, IBM now attracts a greater share of customers’ wallets than ever before, especially in the high-margin markets where IBM has made strategic investments. This is precisely what the company had hoped when it decided to drop lower-margin businesses that company leaders believed would not help create sales synergy going forward.

What Disney and IBM make look easy, however, is in reality very difficult. Even if a company is smart enough or lucky enough to develop multiple business models, the challenge of managing them is daunting. Technology evolutions make this difficult, as do changes in market conditions, customer buying habits, regulatory environments, and even political administrations. New business models often mean embracing new governance models, funding constructs, resource challenges, logistical obstacles, and more. Most companies, even successful ones, lack either the courage or the discipline to manage multiple business models or just shy away from the effort required due to concerns over focus and resources. They are loathe to divert resources from their primary revenue stream or to risk cannibalizing it. They are especially unlikely to make changes during the good economic times that afford them the greatest flexibility and freedom.

What most companies fail to recognize is that the inability to simultaneously pursue new and existing business models inhibits an organization from developing capabilities that it might need in the future both to exploit new opportunities and to defend itself against competitive threats. While companies like IBM and Google develop new business models to diversify their operations, others, including Amazon, have used business models to disrupt mature markets. Because brick and mortar book retailers were slow to adapt to online business models, Amazon was able to exploit the online model and thus take market share from Barnes and Noble, Borders, and others.

As Amazon and others have demonstrated, companies that do successfully embrace new business models can make significant gains that can radically change their competitiveness. Take Apple, for instance. From its founding in 1976, Apple’s core business was hardware manufacturing and software development. Its products changed dramatically over the course of the company’s first 25 years, but its fundamental business model did not. Apple made computer products and sold them through retailers, dealers, and mail order houses to customers around the world.

Then in the early years of the new millennium, Apple made a series of moves that would ultimately change the mix of its business models. To create a more consistent end-to-end customer buying experience, Apple opened its first retail stores in 2001. Then it introduced a disruptive technology, the revolutionary iPod music player, in October of 2001. Apple followed the launch of the iPod with a new business model that would change its trajectory even more dramatically. That was the Apple iTunes digital music store.

At the time, music downloads over the Internet were on shaky ground. Napster, a brash early innovator, was facing mounting legal challenges, while alternative models were floundering. Apple, however, believed that legal downloads of music, movies, and television programs would revolutionize the entertainment experience. And it seemed to have perfected a winning formula. Apple first secured participation from virtually every major record label. Then it created a visually appealing virtual storefront on which it showcased all but a handful of the most well-known artists in the business. Finally, it made music available one song at a time, all for the universal price of $0.99.

The combination of an elegant, innovative music player combined with an intuitive, convenient online store provided a new revenue stream that literally changed the company’s fortunes. Since developing the new business model, Apple has sold more than six billion songs and millions of movies and television shows. The company now sells more music than any other retailer. iTunes is a $3 billion revenue stream that also fuels the sale of iPods. In fact, Apple now generates more revenue from its iPod product line than it amassed in total sales as a company during the year prior to the October 2001 iPod launch.3 The impact on the company as a whole has been nothing short of revolutionary. Total sales today are now almost seven times what they were in 2001. The company’s market capitalization, not surprisingly, has increased by more than 400 percent in just five years.4 If ever there were a showcase example of the transformative powers of a new business model, Apple could be it.

And so could Cisco, if all goes according to plan.

Like Apple, Cisco has benefited handsomely from its embrace of new business models. But it hasn’t been easy. Cisco’s primary business model—high-value, high-margin networking products sold with partners via high-touch sales engagements—doesn’t always transfer well to adjacent markets. In addition to new margin structures, Cisco has had to master different go-to-market strategies, new competitors and higher-profile branding challenges, among other things. As you might suspect, some efforts have turned out better than others. That’s a polite way of saying some things tanked. But over the course of several attempts, Cisco has learned the value that can be created by pursuing both new and existing business models, and then leveraging the best from both the way Apple has done so successfully with its Macintosh computers, iPod music players, iPhone devices, and iTunes music service.

Like BYD, Cisco is constantly on the lookout for market transitions and their associated opportunities. When it spots an opportunity that fits into its overall vision, the company will pursue it regardless of whether its existing business model supports it. If the opportunity requires the adoption of a new way of doing business, Cisco will not back off. It will either develop the model required to make the most of a market transition or acquire it from a company that already has.

To Cisco, the challenges associated with developing a new business model are small compared to the loss of missing out on an important market transition.

In the pages that follow, I examine how Cisco developed new business models around opportunities such as the consumer market, custom-built video solutions, services, and collaboration software sold not as a product, but as a service. The knowledge collected from these experiences has launched the company on a new trajectory and given it the assurance that sitting idly by while markets churn or technologies change is rarely the right decision. Difficult though it may be, mustering the will to try something new, even when it threatens an existing line of revenue, has served Cisco well. Consider its expansion into consumer products, for example.

Volume Operations: A Business Model for the Consumer Market

Cisco CEO John Chambers tells a funny story about how he first came to understand the nuances of the consumer market. That’s shortly after his son installed a wireless network in the family’s home. “I assume you used Cisco products,” said Chambers. But his son said he didn’t because he couldn’t find Cisco products at the retail location where he shopped. Nor could he find ones at a suitable price point online. Cisco’s gear was simply too expensive and too technically advanced for his needs.

Chambers made a mental note about his son’s experience. When he started asking his lieutenants if it was an isolated case, he was chagrinned by their response. “No,” he was told, again and again.

That didn’t sit well with the CEO, who saw huge potential in the consumer segment. At the time, the market for home and small office network connectivity products was already a $20 billion market opportunity and forecasted to grow as large as a $74 billion opportunity by 2009.5 There was simply no way Chambers could allow Cisco to bypass that market. If consumers by the millions were networking their living spaces with inexpensive, easy-to-use routers, then Cisco ought to be at the center of this communications revolution, he believed.

But Cisco wasn’t, and the reason was fairly obvious: The company’s products were simply too expensive or too complex for most consumers. This wasn’t due to poor pricing policies or inept engineering, but the company’s vaunted business model, which produced as much wealth as all but a handful of companies in the twentieth century. To this day, Cisco’s core business model relies on specific financial underpinnings without which the business cannot thrive. Cisco, for example, has traditionally aimed to achieve gross margins of 65 percent. But lower prices and steep competition makes that impossible in the consumer space, where margins of 30 percent or less are common.

What this means is that companies who compete in the consumer market have to accept some steep compromises. They cannot afford to plough 10–20 percent of revenue back into R&D. After paying distribution, branding, and other costs, consumer products manufacturers typically have around 2–3 percent of revenue left for R&D investment. Likewise, the economics of the consumer market all but eliminate the ability to offer generous customer support or flexible returns policies.

As a result, Cisco was stymied every time it tried to expand into the consumer market with its existing business model. But the market was too big and compelling to pass up. In addition to the incremental sales that could be won in the consumer space, the market offered Cisco an opportunity to increase its relevance with customers and industry watchers alike. Consider: In most markets, Cisco sold products that were largely invisible to all but a few networking professionals and technology enthusiasts. But the consumer market offered Cisco an opportunity to sell end-user devices or endpoints that customers could see and touch for themselves.

If Cisco could cement itself as the provider of networking devices for major service providers and the maker of endpoints sold to consumers, it could achieve a level of architectural influence that no other company enjoyed. But attaining that value proposition wouldn’t come easy.

After several attempts to make a dent in the consumer market, Cisco could appreciate the differences between selling thousands of products priced as high as $500,000 to IT professionals versus selling millions of products priced around $50 to individual consumers. Try as it might, Cisco simply could not stretch its existing business model sufficiently to cover the consumer market. It needed a new, purpose-built business model expressly tailored to this growing segment. Among other things, this model needed to be independent from Cisco’s core business and fully operational as soon as possible so Cisco wouldn’t miss out on a great wave of customer buying. Given these realities, Cisco recognized that the right approach to creating the new business model would be to acquire it rather than to build it. This decision was based on how different the new business model was and how quickly it needed to be launched. Cisco chose to acquire the new business model from a company with a growing footprint in the market. The company it chose was Linksys, the maker of the equipment Chambers’ son bought when it came time to install wireless connectivity in his home.

Founded in a garage in Irvine, California, in 1988 by the husband and wife team of Victor and Janie Tsao, Linksys was already a consumer networking powerhouse when Cisco came calling in 2003. Linksys had more than $400 million in annual revenue and employed more than 300 people.

From the onset, Cisco understood that it was getting into a very different business. Never before had it sold products in stores that offered Bubblicious chewing gum or Britney Spears CDs. To prevent the new business model from imploding, Cisco’s management team kept much of Linksys independent, at least at the onset. They integrated common business functions, such as HR and finance, but preserved unique aspects of the company such as its engineering, sales, and marketing. Linksys, after all, was a market leader, and Cisco was eager to learn from its expertise.

The hands-off approach worked. Since the acquisition, Linksys has maintained or improved on its business metrics. Annual sales, for example, have doubled. Meanwhile, Linksys has also diversified its business and entered new markets. Today, a quarter of sales come from outside the United States—more than doubling the rate they were at a few years ago.

Thanks to its maniacal focus on enabling a separate business model, Cisco better understands branding, the retail channel, and the consumer market supply chain. Not surprisingly, the new business model, anchored in low gross margins and high volume sales, remains intact. And with this model, Cisco is inching closer to its vision of becoming a consumer-friendly company that sells devices, software, and services as an integrated solution. If not for its adoption of a new business model, Cisco might have missed out on this large and growing opportunity in the home networking market.

But the company soon realized that for all its accomplishment in the consumer space, plenty of other business models were yet to be developed if Cisco was going to expand its horizons even further.

Custom-Built: A Business Model for the Video Market

Not long after Cisco adopted a consumer business model, the company realized that rising interest in the Internet was pulling it into the complete opposite direction—toward the very companies providing consumers the Internet and broadcast content they so wanted. These companies are, of course, the world’s leading telecommunications giants, cable television companies, and other service providers whose fortunes are increasingly linked to providing Internet connectivity, digital television, and IP communications.

Cisco already generated about a third of its sales from service providers, mostly from the sale of routers and switches that served as their networking infrastructure. But Cisco had yet to help the service providers sell video and other networking services to their customers. The reason was simple: Cisco lacked the technical expertise and the customized offerings needed to serve these companies to their satisfaction.

Unlike consumers, these customers don’t buy anything off the shelf. They demand everything be customized for them because they believe their ability to create unique or differentiated experiences for their customers lies in the customized pieces of hardware gear and software applications they require.

Cisco, of course, longed to be the company that supplied these products to the communications giants. The difference between its capabilities and its desires at the time was akin to altering a suit bought off the rack versus tailoring one from scratch. Cisco was superb at the former, but it had limited experience with the latter. It needed a business model suited to custom-built solutions.

Without that capability, Cisco could get in only so deep with this set of customers. Once again, the company found itself poised to take advantage of an adjacent market opportunity but constrained by its traditional business model.

One reason Cisco leaders were so keen on developing a model that could cater to individual needs of large service providers was their growing interest in a technology that Cisco saw as key to its own future: video.

Video, of course, puts tremendous demand on communications and information networks and thus drives up the demand for the connectivity products that are the backbone of Cisco’s product arsenal. Think about it: One hour of high-definition video consumes more bandwidth than a typical small company’s email traffic consumes in a year.

You probably know that the number of videos uploaded to the Internet every day has been soaring at an astounding rate. Nearly 24 hours’ worth of video is uploaded to YouTube every minute—four times as much as was uploaded just two years ago.6 Not surprisingly, viewership is also rising rapidly. In April 2009, 17 billion video streams were initiated by Internet users in the United States. The total viewing time was almost 60 billion minutes or one billion hours.7 That’s roughly 6 minutes of video watched every day for every man, woman, and child in the United States.

All that consumption is straining the Internet like never before. Consider the impact on bandwidth of just one video: “The Last Lecture,” a video of Carnegie Mellon University professor Randy Pausch delivering his final address to students shortly before his death in 2008. The emotional presentation became a viral sensation after it hit the Internet, and the understated, thoughtful professor became an unlikely media celebrity and bestselling author. As of this writing, “The Last Lecture” has been viewed more than 11 million times on YouTube, generating 3 petabytes of Internet traffic. The network traffic created by this single video is greater than all the traffic over the Internet before 1995. Staggering.

To manage the bandwidth required for video, voice, and data communications, Cisco knew that customers would need more than powerful routers and world-class switches; they would need a complete end-to-end digital solution for managing and distributing video.

Faced with the reality that it didn’t have the video technology that service providers needed or the custom-built business model for catering to them, Cisco had to make a choice. It could either develop these skills internally at great cost and over a long period of time, or it could pursue another acquisition. That led it to Scientific Atlanta (SA), which Cisco acquired for $6.9 billion in 2005.

Founded in 1951, SA is best known for its set-top boxes, which are used by millions of cable TV subscribers. In addition to these devices, the company produces a complete line of video production and delivery tools and services, providing an end-to-end video solution for broadcasters, cable television companies, and production companies. Though its products are used by everyday citizens, SA’s go-to-market model is anything but consumer-oriented. In contrast to Linksys, which sells items costing about $50 to millions of customers, SA’s business is substantially more focused. Its top five customers, for example, average more than $200 million each in annual purchases. When Cisco approached SA, one single SA contract with Time-Warner was annually worth nearly as much as all of Linksys’ annual sales.

Cisco had dealt with big customers before, but not in the way or scale in which SA did every day. SA operated with a level of service and a degree of customization that was unimaginable to Cisco. It often received last minute requests for product modifications. These would have strained Cisco’s supply chain. But SA, which owns a custom-manufacturing facility in Juarez, Mexico, routinely accommodated these demands.

SA boasted a vertically-integrated, custom-built business model that enabled the company to custom-build virtually any set-top box. Managing that kind of operation and measuring its efficacy was completely foreign to Cisco. But SA had perfected it over the years. Among other things, SA developed an intimacy with customers that was new to Cisco. The executive team boasted deep, long-standing relationships with key customers—associations that had long since moved from the boardroom and into the realm of social interactions and personal friendships.

Given the differences between the Cisco and SA business models, it was decided to leave SA intact initially, until the leadership teams could map out a way to integrate SA in a mutually beneficial fashion. Over the course of three years, Cisco has integrated many go-to-market elements. More recently, Cisco has identified very specific cross-leverage plans. For example, Cisco has embraced SA’s custom-built service provider model, integrating it throughout the company in every department from engineering to sales to services to help large scale telecommunications service providers. Cisco is also embracing some of the skills and techniques that SA uses to develop and nurture relationships with the CEOs of major service providers.

The Cisco/SA relationship has been mutually beneficial. In addition to the benefits that flowed to Cisco, many others flowed to SA. For example, Cisco enabled SA to expand into new geographies. At the time of the acquisition, SA had little penetration in global markets, due to the complexity of scaling its ultra high-touch model. Cisco, which generates more than half its business outside the United States, leveraged its existing relationships around the world to help SA break into new territories. Because of this, SA has flourished and is now engaged with key Cisco customers around the world.

And the result? SA’s $2 billion business grew by more than 40 percent in the first two years after the acquisition, exceeding expectations.

By adopting volume-based and custom-built business models, Cisco positioned itself to serve the consumer and service provider markets more effectively.

By almost any measure, developing these two different business models at opposite ends of the spectrum simultaneously has paid off. One launched Cisco into the consumer market, while the other dramatically increased its penetration with telecommunications service providers.

An entirely different model allowed Cisco to begin servicing customers on an annuity basis years earlier.

Subscriptions: Monetizing Software Through Services

In the early 1990s, Cisco was a small, albeit fast-growing, company. Customers clamored for its networking products but also needed technical support, given the advanced nature of the technology. Like most companies, Cisco offered after-market service, mostly of the break/fix nature.

As time progressed, however, Cisco’s technology evolved. So, too, did customers’ dependence on it—if not for critical needs then certainly for day-to-day operations. As a result, customers began asking for greater assurances from Cisco. What they wanted, in essence, was greater support than Cisco previously provided. And to complicate the problem, customers increasingly wanted this support in geographies where Cisco had a limited footprint.

That posed a dilemma for Cisco. To better serve its customers, the company had to choose between building a significant worldwide services organization, and developing a new services model in conjunction with its partners. It wasn’t an easy decision, given the enormous pressure top customers put on Cisco. They wanted the company to build a services business that would cater to them directly, but Cisco’s partners had better access to them. After much deliberation, Cisco concluded it could best cater to customers’ needs by creating a mechanism that maximized both Cisco’s know-how and partners’ abilities.

Knowing he couldn’t let customers languish without adequate support, CEO John Chambers decided to build a services business in conjunction with partners. But while Cisco had the intellectual property and the technical expertise that customers wanted, it lacked the business model to provide it. Cisco’s financial engine was built around products sold as single transactions, not around services, which were typically delivered as annuities over specific periods of time.

Unlike other tech giants, such as IBM or Hewlett Packard, Cisco did not want to build a full-scale, people-intensive business. Instead, it decided to develop a modest services arm to improve customer satisfaction and accelerate technology absorption, which was hampered because customers could not easily install and operate advanced Cisco products.

Because a services business is so different than a product business—think technical support and software updates instead of equipment flowing down an assembly line, and ongoing subscriptions instead of capital expenditures—the company had to develop new practices to make it successful. Chambers hired Doug Allred, a high-tech customer support executive, to develop a services business at Cisco.

Chambers gave Allred a series of key objectives: Take care of customers, increase technology absorption, earn high margins, and create a mechanism that will scale quickly around the world. With these requirements in mind, Allred began looking at options with a team that included Joe Pinto, Cisco’s current senior vice president of technical services.

Customers, the team knew, needed technical support and software upgrades delivered in a more consistent fashion. But because they bought it in such an unpredictable way, Cisco struggled to monetize the business to the degree required to sustain it. Cisco realized that the complexity of its products meant that a software upgrade alone would not be sufficient for most customers; they would need a service contract that also covered advanced product replacement, online resources, and technical support.

So the new services team made a strategic decision. Cisco would offer partners the deal of a lifetime: Partners could sell lifetime service contracts of any value on Cisco equipment. In exchange, Cisco would charge them only a small percentage of the list price of any product for just a few years. The only requirement was that the partners build Cisco support capability and send their support engineers for advanced Cisco certification training. Otherwise, the terms were remarkably attractive and thousands of partners decided to create services businesses around Cisco’s products.

In return, Cisco got support coverage for its customers and a predictable revenue flow to sustain the business.

With the services business monetized to the point where it was stable and predictable, Cisco began investing in best practices and other benefits for customers. Among other things, Pinto decided to publish a list of all known technical glitches or “bugs” found in Cisco products. This was unprecedented among technology companies, which have a long history of downplaying or even denying the existence of bugs in their products. While the candor surprised many in the industry, the decision to publish the list for customers’ benefit ultimately won the company a great deal of goodwill among customers and helped reduce concerns they had about signing service contracts.

“Our transparency with our customers became a cornerstone of our support success,” says Pinto. “It was really transformative.”

So was the impact of services. By embracing a new business model, Cisco could better serve customers and help its business partners improve the profitability of their businesses. Cisco also drove growth by removing barriers to technology absorption, while adding a high-margin, annuity-based revenue stream.

One reason for the consistently high margins: Cisco promotes a self-help approach to support, leveraging its own technology. As a result, more than 80 percent of all Cisco support issues are resolved online, versus the industry average of 29 percent. By throwing intellectual property, rather than people, at the problem, Cisco improves its customer satisfaction, scales its engineering resources, and amplifies its gross margins. These high margins enable the company to reinvest in even more intellectual property, perpetuating a cycle of innovation. The business model has also grown from reactive, to responsive, to proactive, adding capabilities along the way. And the journey continues to this day, as services becomes more knowledge-centric under the leadership of Executive Vice President Gary Moore.

The new business model and the subsequent refinements worked. Services turned into a robust success for Cisco. Its gross margins exceed 65 percent—twice the industry norm—and it accounts for $7 billion in annual revenue, or one-fifth of the company’s overall sales. In fiscal year 2008, Cisco services revenue grew at an annual rate of 18 percent—outpacing the growth of several of Cisco’s best selling products.

Moreover, the move into services gave Cisco great confidence that it could indeed prosper with a subscription model every bit as much a traditional product sales model. The knowledge and self-assuredness Cisco developed in services came in handy when another market transition occurred in software. That was the shift from license sales to Software as a Service (SaaS). When this happened, it presented a golden opportunity for Cisco to take advantage of its experience with a subscription model to build a leadership position in collaboration.

Software as a Service: A New Way to Engage Customers

In the world of automobile manufacturing, few things excite customers more than the arrival of a new vehicle. It can prick up the ears of drivers thinking about a trade-in and attract attention from enthusiasts looking for something shiny and new.

When Subaru of America debuted the Tribeca in 2006, the company attracted more than the usual amount of attention. Its new vehicle, an upscale sports utility vehicle, was the company’s first foray into the luxury car segment and came out at a time when sales were soaring in the United States.

To prepare dealers for a new category of customers, Subaru wanted to train its salespeople. But Darryl Draper, Subaru’s national customer relations and loyalty training manager, worried that she could not reach all of the company’s dealers before the new vehicle arrived in showrooms. After considering her options, she decided to deviate from her tried and true training method, which revolved around physically visiting every dealer. For the Tribeca, she would use the Internet.

It was a radical but theoretically feasible option given the rise of a new type of technology: web conferencing and collaboration software. Draper selected an application, developed content, and launched Subaru’s training program. Within six months, she connected with 98 percent of the company’s dealers and did so for a fraction of what she normally spent on training. Thanks to the collaboration software, Draper reduced training costs per person to just $0.75 per salesperson. “No other program in Subaru’s history has achieved these types of results,” she said.8 With results like that, it’s no wonder that collaboration is a hot category in software. More than a mere training vehicle, web conferencing and collaboration software enable an entirely new way to communicate, share information, and engage people. Among other things, it enables geographically dispersed people to host meetings with one another and jointly work together over the Internet. They can use it to share documents, host video conferencing calls with multiple participants, and deliver presentations for an almost unlimited audience. The software is a tremendous productivity tool that can reduce the distance between people and the time that separates them.

As you might imagine, sales are soaring. In 2008, worldwide sales of web conference and team collaboration software jumped 22 percent over 2007 to nearly $2 billion.9 In an otherwise down economy, that’s very strong growth.

The more Cisco looked at collaboration, the more it believed it held the promise to transform business. That’s why it wanted a piece of that fast-growing market. However, Cisco was stymied by the way in which customers were consuming web conference and collaboration software. Rather than buying it outright in the traditional, software-licensing sense, customers were opting to pay for it as a subscription, otherwise known as Software as a Service (SaaS).

SaaS, much to the chagrin of traditional software companies, has been growing in popularity in the past five years. One of its earliest proponents, Salesforce.com, is already a $1 billion powerhouse in the world of business applications.

SaaS provides customers a more flexible and scalable way to pay for the software they use. For starters, customers don’t generally need to install additional hardware or software in their infrastructure in order to use SaaS. Instead, they only need to be online to avail themselves of services that essentially live on the Internet, also known as the networking cloud. Among the benefits of this model is the reduced time required for customers to get up and running. Unlike traditional software applications, which can take weeks, months, and even years to roll out in a large enterprise, SaaS applications can be turned on almost instantly. SaaS is also easier on customers’ wallets. It typically draws from a company’s operating budget instead of its capital outlay, so signing up for SaaS doesn’t require committing to a large, upfront expenditure. Because of this, customers can more easily match their spending to their needs.

SaaS also provides many benefits to software companies. Rather than sell their intellectual property as a product license in a one-time transaction, software developers can offer their work in a more flexible fashion, tailoring pricing plans to the individual needs of their customers. As a result, they can count on revenue to pour in over a measured period of time, rather than in unpredictable spurts followed by periods of drought. That’s made the business of developing code less of a mad-dash and more of a deliberate run at a sustainable pace.

Cisco felt an urgency to enter the new space, given the eagerness of customers to buy and the onslaught of potential competitors. But the company was a newcomer to SaaS, which had rhythms and nuances all its own. The market, while adjacent to Cisco’s existing areas of expertise, was different. It required an entirely new business model.

Cisco would need to become, in essence, a service provider, to host the applications associated with SaaS. That meant developing massive backend infrastructure and operating large data centers in order to provide subscription-based services for a monthly fee. Cisco would even need to compete with some of its own service provider customers. And for a company accustomed to dealing in large capital expenditures, the subscription-based services represented a major change to Cisco’s selling model. Faced with these challenges, Cisco again looked outside its own walls for an existing business that could help launch it quickly into this market. It found what it was looking for in WebEx, which it acquired for $3.2 billion in 2007.

WebEx not only offered Cisco a hot new technology in a category for which it had great affinity, but it also provided an excellent opportunity for Cisco to make inroads in the small business market. This market had always viewed Cisco as a desirable, albeit expensive, supplier of networking gear for corporate customers. With WebEx and its small business-friendly SaaS model, Cisco had the opportunity to engage millions of potential new customers—including Subaru dealerships, which leveraged WebEx for its successful online training program.

Since the acquisition, Cisco has learned volumes about software pricing, upgrade cycles, and even new sales techniques related to the SaaS way of doing business. With a better understanding of the SaaS market under its belt, Cisco has worked to integrate WebEx into its broader go-to-market strategy. Cisco partners are now being recruited to support the WebEx platform and introduce it into their accounts, while Cisco’s salespeople are incented to offer the technology to enterprise customers.

Before WebEx, Cisco simply didn’t have the proper knowledge of billing practices, sales techniques, or development procedures required for this type of business. Nor did it have a way to help customers accommodate broad IT changes. “From a technological standpoint, Cisco clearly saw where the market was going in terms of cloud computing and SaaS. But that was only half of what it takes to be a leader in this market,” says WebEx co-founder and Cisco vice president Subrah Iyar. “The other part of the challenge is developing the underlying business model that will allow a company to take its products and services to market in a way that customers want to consume it. Through WebEx, Cisco quickly got the technology it wanted and the business model that it needed to be a leader in this market.”

While more challenges remain, the new model is working well so far—so much that WebEx net product bookings grew more than 40 percent in the first year after the acquisition.

Model Behavior

By once again doing both—pursuing new and existing business models alike—Cisco has positioned itself to be as nimble as it is strong and as flexible as it is precise. That helps when market transitions occur and every other day of the year, too.

Many companies resist new business models, fearing the inherent risks associated with them. And it’s true that Cisco won’t implement just any model. But if a business model has the potential to help Cisco capture a market transition or better serve its customers, then the company is quick to embrace it, whether by organic development or external acquisition. And Cisco has, by trial and error, developed best practices for each.

Of course, Cisco’s efforts remain a work in progress. But the results to date are compelling. Because it embraced new and unfamiliar business models, Cisco is making inroads in previously inaccessible markets. In 2009, for example, Cisco generated $7 billion from services, $3.5 billion from video, and is approaching $1 billion each from the consumer market and from collaboration sold as a service. That’s almost one-third of the company’s sales—an impossibility without the embrace of a new way of doing business.

Such diversity, of course, has made Cisco a stronger company with a wider customer base and a deeper product portfolio. This is providing Cisco the kind of financial strength and resilience that used to be the stuff of fiction.

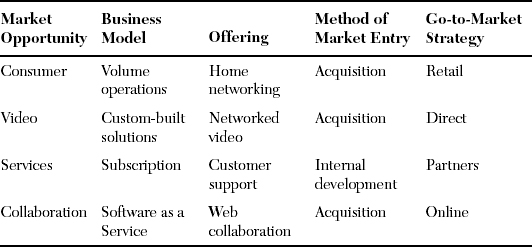

But getting to this point required some heavy lifting and some new thinking by company leaders (Table 3.1). They had to open their minds to developing capabilities in disciplines they had never before mastered.

Table 3.1. Summary of New Business Models

Think about that the first time a silent, emission-free, electric car from China zooms past you in a flash of metal and chrome. In your rush to seize a photo of that technological marvel with your mobile phone, remember that BYD built that car on the profits it made from the battery inside that phone. Like Cisco, it was willing to step outside its comfort zone to embrace a new business model.

In doing so, it may change the world.