Chapter 7. Doing Things Right and Doing What Matters: Excellence and Relevance

“A truly 21st century idea.” “Bigger than the Internet.” “More important than the personal computer.”

These were just a few of the early impressions of the Segway Personal Transporter, one of the most celebrated innovations of the last several decades. The first technological marvel of the new millennium, the scooter was expected to revolutionize transportation. Inventor Dean Kamen predicted his two-wheeled device would be to the car “what the car was to the horse and buggy.”1

So much for great expectations.

When the much anticipated invention went on sale in 2002, the public yawned. Shortly thereafter, new-age observer Wired magazine went so far as to sneer, “It would be premature to call the most-talked about scooter in the history of human-kind a huge bust. But the Segway has always been ahead of its time.”2

Ouch.

Nearly a decade after its unveiling, it’s clear to most that the Segway has not changed the way cities are designed, nor the way people get around their neighborhoods. Aside from mall and airport security personnel and a relative handful of postal workers, the Segway is a curiosity to most, a nuisance to others. Even environmentally conscious and technologically progressive San Francisco ruled against the Segway in 2002, when city officials voted to ban the device from the city’s sidewalks due to safety concerns.3

So where did Segway go wrong? Certainly not in the design or execution of the two-wheeled device, which is a true marvel. Ingeniously conceived, the Segway overcomes numerous technological challenges, not the least of which is staying upright and safe under the most challenging of circumstances. The Segway can calculate a user’s center of gravity 100 times per second and operate in all kinds of weather.4 It can move along at a top speed of 13 miles per hour—roughly what a world-class marathoner achieves—and stop on a dime. The device produces no carbon emissions and requires little training to operate. And yet it’s a commercial flop.

Consider: The Segway factory was designed to produce 40,000 units per month. As of August 2009, however, only 50,000 Segway scooters had been sold—a tiny fraction of original expectations.5 To say the device has underperformed is an understatement, especially when you consider the high profile of some of its backers. Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos, for one, called the scooter, “one of the most famous and anticipated product introductions of all time.” Silicon Valley investor and serial entrepreneur John Doerr, likewise, had similarly high hopes for the device. He famously predicted that Segway would be the fastest company in history to reach $1 billion in sales.

That didn’t happen, of course. Why? For all its technical excellence, the Segway scooter failed to prove its relevance to customers.

Despite the tens of millions of dollars that it took to develop and the patented innovations that were required to produce it, the heavy and over-priced Segway turned out to be a niche product at best, ably helping service workers and public safety professionals in a variety of settings, but hardly changing the world.

That may never have happened had the Segway proven relevant to customers. But relevance simply wasn’t as attainable as excellence.

Ironically, a similar fate often awaits those who achieve relevance without excellence. Take the companies behind plastic recycling, for example. In these environmentally conscious times, what could be more relevant? Despite overwhelming interest, however, less than 1 percent of all polystyrene containers like yogurt cups are recycled in the United States today.6

The reason is simple: There’s no excellence in the process.

Polystyrene is difficult to separate from other forms of plastic and thus confounds consumers, even environmentally conscious ones. It also requires extensive cleaning and special equipment to process and produces its own greenhouse emissions. In addition, the economics of polystyrene recycling don’t yet add up for many of those trying to make a business of it. One ton of this material sells for less than $1,000 and commands much less on the open, scrap market. Given that widely used foam versions of the product are 98 percent air, a ton requires a vast amount of storage space and trucking resources, further diminishing the value of collecting it.

In the last decade, many companies that have tried to make money from recycling polystyrene have failed, and entire cities have given up collecting it. Even environmentalists in some of the country’s most progressive communities have been forced to concede defeat. That includes the NextStep Recycling center in Eugene, Oregon, for example. “We wish we could continue to provide this much needed service for our community, but we are losing money with every piece of foam we accept,” says Lorraine Kerwood, executive director at NextStep.7

While recycling processes are improving, the sad fact remains, as Popular Mechanics magazine summarized in 2008, “Most of the plastic put in recycling bins ends up in the garbage.”

What the backers of plastic recycling have come to learn is a lesson that Segway knows all too well: It is impossible for an organization or industry to reach its full potential without both excellence and relevance.

Focusing on one at the expense of the other is simply bad business.

Cisco, too, had to learn this lesson.

Like the company behind the Segway scooter, Cisco had a harder time achieving broad relevance than it did demonstrating excellence. The latter didn’t come effortlessly—quite to the contrary—but it was achieved first.

As the world’s most successful manufacturer of computer networking equipment, Cisco provides the bulk of the infrastructure that powers the Internet and other networks, both public and private. When you send an email, visit a web page, connect to a secured corporate network or, increasingly, make a simple phone call, chances are Cisco equipment or software made it happen.

As a reminder, Cisco sells products and services to customers of all sizes and does business in more than 140 countries. In its 25 years of business, the company has made more than 130 acquisitions, been named to the top of countless lists of best places to work for, and risen to the top of the corporate world. The company is number 57 on the Fortune 500 list of the largest industrial companies8 and has a market capitalization, as of writing, of more than $140 billion.

With innovations like the Cisco CRS-1 Router, which can download the entire printed collection of the United States Library of Congress in just 4.6 seconds (a feat that would take 82 years with a dial-up modem), Cisco continues to demonstrate this excellence today.9 Cisco is number one or number two in every market and technology category in which it competes.

But for all its excellence, Cisco wasn’t always relevant with business decision-makers. IT executives, of course, regarded it as an important supplier of technology for connecting different electronic devices inside their organizations. But CEOs, CFOs, and other business leaders didn’t look for inspiring or transformational ideas in the wiring closet.

This is the story of how Cisco set out to make itself more relevant. How did the company do it? By zeroing in on what matters most to customers. Put another way, Cisco became excellent by focusing on customer pain points. But it became relevant by moving from customer frustrations to their aspirations. While the journey continues to this day, the story began in a more humble time when the Internet was new, and the possibilities seemed endless.

Walk, Then Run: The First Steps on the Road to Relevancy

Though it seems eons ago, you might still remember the first time you logged onto the Internet. For many people, that was probably in the mid-1990s. Then, there were only a handful of web sites that seemed worth your time. But they were enough to make most of us stop and think: “Wow: This changes everything.”

Sure enough, the Internet did. Within a few short years of becoming widely available to most businesses and consumers, the Internet changed the way we researched, communicated, and shopped, among other things. These early years of the Internet were characterized by the introduction of technologies that paved the way for greater transactional efficiency and improved data collection and dissemination. Thanks to the Internet, individuals could connect directly to information—almost all the world had ever amassed and stored—for the first time in recorded history.

Cisco, of course, benefited handsomely from this phenomenon. But while its sales and market capitalization grew to record heights, its relevance lagged. CEOs and other business leaders perceived the technology upstart as a worthwhile vendor, but not necessarily a thought leader that could transform their businesses. Most of their focus was directed at the traditional aspects of their operations, which networking technology had yet to transform.

Cisco believed that it could resonate with business decision-makers if it could show them how an organization that leveraged networking technology could increase its productivity, better serve customers, and improve its competitiveness. Unfortunately for Cisco, there were no good examples of this at the time. Various organizations were doing interesting things with the Internet, but no major company had gambled to run the key functions of its business with networking technology. So Cisco CEO John Chambers told his lieutenants that Cisco would be the first. He pushed them to think creatively and to apply Cisco and other relevant technology to all aspects of the business. That included sales, manufacturing, marketing, finance—everything. If we can’t drive our own business results with our technology, he challenged, then how can we expect our customers to do so? In other words, use our technology to drive business results, he said, and our relevance will grow.

Cisco-on-Cisco: Making Technology Relevant

When Cisco first began applying networking technology to its business, it did so in fairly obvious ways. It connected workers to data and to basic services, for example. But then it looked more deeply at its business. Rather than augment manual processes with technology, the company began to transform them with technology.

This led to a new way of doing business at Cisco, otherwise known as Cisco-on-Cisco. It was the company’s strategy of using Cisco technology to improve business results. In other words, Cisco ran its own critical business functions using its own technology. The effort led to the creation of a slew of productivity and efficiency applications, especially in the areas of employee self-service, customer support, product configuration, and supply chain management. In time, Cisco came to run its entire business on Internet technology. An internal study pegged the benefits at $960 million annually in the late 1990s.

Take the Cisco web site, for example. Known as Cisco Information Online when it was implemented in the 1990s, it provided online customer support for most inquiries. By 2000, more than 80 percent of all technical support questions were handled directly over the Web, including many being answered by a community of users, years before the advent of social networking. The company saved $200 million annually by moving support from the phone to the Web. But a more important benefit quickly emerged: The quality and consistency of customer support improved, and customer satisfaction increased at a fraction of the cost.

Cisco also built an extensive online ordering capability where dealers could configure product orders to customers’ needs and track them from ordering through manufacturing to delivery. This enhanced the ease of doing business with Cisco and even attracted competing resellers who were fed up with other vendors’ phone- and fax-based order-entry systems. As Cisco business quadrupled, the number of customer service representatives stayed relatively flat.

Cisco-on-Cisco, of course, didn’t stop with a few e-business applications. In time it grew to include nearly the entire Cisco portfolio. After the company entered the voice market, it replaced all of its traditional desktop phones with those that ran over the Internet instead. Given the relative instability of Internet telephones at the time, the move was quite controversial. But it underscored Cisco’s commitment to demonstrating the transformational value that Cisco networking technology could provide. It also allowed the company to fix the stability problems before bringing those phones to market.

The more Internet-enabled solutions Cisco deployed to help run the company, the more customers began asking questions. But instead of mere technical questions, they began seeking answers to business problems. Over time, Cisco-on-Cisco became the most requested presentation in Cisco’s customer briefing centers. The gains that Cisco claimed to be getting from “eating its own dog food” began to resonate well beyond customers’ IT departments. Cisco was transacting 90 percent of its orders—$60 million per day—over the Internet, and resolving 80 percent of customer support cases through web-based, self-service applications.

Suddenly, business customers saw Cisco in a whole new light.

New Models for a New Era: How Process Drove Relevance

Despite this initial success, Cisco knew that these technological changes would only increase the company’s relevance so much. Because of this, Cisco recognized that it would have to drive change deeper inside its organization. That, however, required key process changes, including how the company funded IT projects internally. Rather than pay for new initiatives out of a centralized IT pool, Cisco shrunk its IT budget and then reallocated much of that money to individual business units. IT would pay for the things that were central to the entire company and benefited from being done just once, but individual business units and functional teams would be required to allocate funds for individual projects if they wanted IT to complete these projects.

The entire company felt the impact of these client-funded projects, as they came to be known. Among other things, department heads and business leaders changed how they approached the design, development, and deployment of applications and services key to their business functions. With their own dollars on the line, business leaders became more careful about the projects they pursued and more involved in implementing new technology that would drive their business objectives. Like any external Cisco customer, they made sure that any outlay of funds was relevant to their business needs.

Thanks to the introduction of the client-funded model, Cisco drastically reduced the number of wasteful IT projects that received a green light. Furthermore, the projects that did get funding were almost always delivered on time.

As for the budget dollars that the IT department returned to the business? They came pouring back into IT, fully aligned with the business priorities. In fact, IT investment at Cisco actually increased when business units began funding their own projects. In less than three years, IT spending as a percent of revenue doubled at the company. And it was being spent on projects relevant to business needs.

Driving a Culture of Accountability

Despite the significant gains Internet technology was bringing to Cisco, including process-related benefits, not every business unit embraced management’s desire for the widespread application of Internet technology. Engineering, for example, was reluctant to embrace new Internet-enabled processes for fear they would cause delays in product development.

But Chambers would have none of that. He believed that convincing business leaders of Cisco’s relevance would be undermined if he couldn’t show them how the technology improved all parts of his own company. So he pushed for universal technology adoption throughout Cisco.

To better align leaders with Cisco’s goals, he and his leadership team launched a study of the Internet-readiness inside the company. Every senior leader was surveyed on his or her openness and ability to leverage the new technology. Upon completion, Cisco discovered that only one-third of the business units were both willing and able to adopt the new technology. A second third of the company’s senior executives believed strongly in the transformative powers of the Internet but lacked the wherewithal to leverage it. The final third of executives, meanwhile, lacked both awareness and basic skills.

For a company once dubbed “most Internet-enabled” by BusinessWeek, this was a disappointment. As the world’s number one supplier of Internet gear, Cisco’s management hoped for higher awareness and interest. But they weren’t shocked. Embracing the Internet for personal enjoyment and benefit is one thing; transforming your organization with it is another, they realized. After considering the survey results, Chambers came to believe that culture was the real impediment to greater Internet use inside the company. To change that, he introduced the Internet Capabilities Review.

Held twice each year beginning in 2000, the Internet Capabilities Reviews required company leaders to stand before the CEO and their peers and outline how they were leveraging the Internet for business gains. To make the task more meaningful, executives had to benchmark their organizations against those deemed best-in-class by Cisco’s own IT department. Chambers expected his team to exceed these benchmarks.

While certain departments struggled with their Internet readiness, the overall progress achieved by these internal sessions was substantial. Virtually every department inside the company eventually developed a cultural affinity with the Internet and all things networkable, while Internet-enabled processes were institutionalized throughout the company.

In time, the Internet Capabilities Reviews were no longer necessary; Cisco was Internet-ready, thanks to the technology, processes, and culture it had put in place.

As a result of these changes, Cisco did indeed elevate its relevance among customers during the first wave of Internet adoption. The first effort made its technology more relevant to the business. The second—client-funded projects—set up a process to ensure the business relevancy of all technology expenditures. And the third, Internet Capabilities Reviews, changed the company’s culture to be more agreeable to technology-driven business results.

The combination of the three—technology, process, and culture—drove Cisco to a far greater degree of relevance, for itself and for its customers.

Suddenly, the CEOs of the world’s largest corporations wanted to learn how the company from the wiring closet transformed its business by embracing Internet technology—and whether Cisco could do the same for them. When Chief Marketing Officer Sue Bostrom led Cisco’s business consulting team, she personally met one-on-one with 270 CEOs—many from Fortune 500 companies—during a single six-month period. And under the leadership of Senior Vice President Gary Bridge, that team—the Cisco Internet Business Solutions Group (IBSG)—continues to drive Cisco’s relevance to this day by engaging with senior executives around the world and showing them how to achieve business results through technology.

By the turn of the century, when the company’s valuation soared above all others for a brief time, Cisco had achieved the relevance it sought for so long.

But another era of innovation was just beginning. Could the company maintain or perhaps even increase its relevance?

Cisco leaders would soon find out.

Collaboration: The Next Revolution

Collaboration.

You do it when you are instant messaging with a friend, debating politics via Twitter, or exchanging status updates on Facebook. Pretty simple, right?

Maybe not. This single word actually represents a revolution. That revolution builds on the foundation of the Internet, adding functionality that is transforming the nature of work.

At its core, collaboration remains what it has always meant—a process for getting multiple people to work together toward a common goal. But Internet-based technology is now taking collaboration to the next level.

With collaboration technology, an aircraft mechanic can confer with distant engine specialists via video to determine the airworthiness of a particular part. Colleagues in different countries can simultaneously edit the same document despite using disparate technology platforms. And an award-winning Hollywood director can direct a movie without stepping foot on the set.

So what can collaboration do for your business? Plenty.

By empowering your employees through collaboration, you can increase your organization’s agility and improve its overall competitiveness. Your employees can use collaboration technology to reduce the time and distance that often separates them from co-workers, customers, and partners. As a result, they can be significantly more productive, no matter where or when they choose to work.

With collaboration technology, businesses can communicate in a more visual and interactive way. They can improve coordination between workers, reduce travel costs, simplify information sharing and improve customer service, among other things.

The timing of these innovations couldn’t be better, given how global economics have changed the composition and demographics of today’s workforce. Thanks to outsourcing and new market expansion, this workforce is more distributed and more interconnected than ever before. The Economist Intelligence Unit estimates that this year, 62 percent of employees will work with colleagues located in different locations, and by 2011, 30 percent of the global workforce will work outside of a traditional, centralized office.10

Cisco recognized that collaboration would be the biggest technology trend of the next decade, driving productivity gains of 5 to 10 percent per year. It created a robust portfolio of collaboration technologies, including TelePresence; WebEx; phones that run over the Internet; devices that produce, distribute, and archive videos; and hardware that can carry, distribute, and manage communications traffic no matter the origin or destination.

Using these technologies internally has helped make Cisco’s workforce one of the most distributed, connected, and productive in the world. Employees have experienced—and driven—a cultural revolution of not only information-sharing, but also teamwork and transparency. In the past year alone for example, TelePresence usage has increased 10 times while WebEx conferencing usage has soared by 25 times. Video postings, meanwhile, have grown by more than 11 times on the company’s internal site.

More than mere statistics, these gains have translated into real business value for Cisco as the company implemented its own collaboration technology internally—just as it did with the Internet 10 years ago. In 2009, Cisco’s IBSG organization calculated the benefits that the company derives annually from its collaboration technology investments.

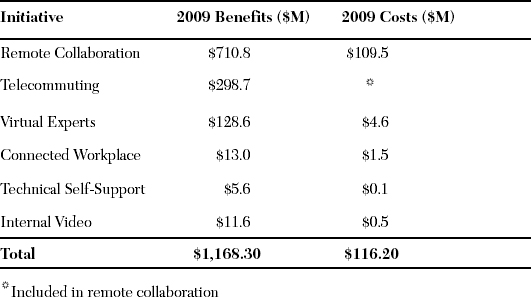

The total amounted to more than $1 billion per year—striking when you consider that this technology has only been around for a few short years. For a more complete breakdown, see Table 7.1.11

Table 7.1. Cisco Collaboration Initiatives: Benefits and Costs ($1,168B − $116M = $1,052B net)

If this sounds awfully familiar, you’re right. This is exactly what Cisco experienced in the 1990s when the Internet first emerged as a game-changer. You’ve already seen how Cisco made itself more relevant to customers by adopting its own Internet technology once before.

And now Cisco is doing it again, starting with the way it scales to interact with customers.

Executive Scaling

Sometime in the middle of the decade, Chambers began to realize that traveling the globe to meet heads of state, lunch with important CEOs, and speak at premier events was making it difficult for him to maintain close relationships with the people he needed to connect with most. Chambers figured he needed to remain personally involved with 50 to 100 key customers, including the CEOs of AT&T, General Electric, Procter & Gamble, and Walmart. But his travel schedule and management obligations left him little time for follow-up and even less for brainstorming. Surely, Chambers, concluded, there had to be a better way, and not just for him, but also for his senior leadership team. And, of course, for his customers.

The answer was Cisco TelePresence, a high-definition video collaboration system. With TelePresence, people continents away can meet as though they were sitting around the same conference table—all with the touch of a button.

The arrival of Cisco TelePresence inspired Chambers and his senior leaders to get even closer to Cisco’s top customers. Collaboration tools, especially TelePresence, accelerate these relationships. Cisco executives can quickly ramp up their involvement with key accounts and participate in ongoing business reviews with their counterparts.

This transformation has strengthened Cisco like few other efforts in the company’s history. Take Chambers, for example. More than saving his back from overnight flights, it has helped him to nurture relationships. Instead of meeting with a CEO one or two times per year, Chambers can huddle virtually with several dozen of them six to ten times per year. Because of the level of rapport that develops with frequent interactions, Chambers can actively engage them in meaningful business discussions. And the same is true not just for his leadership team, but for their counterparts at key customers.

TelePresence, of course, is the closest possible experience to a live meeting. That’s because the sound quality is good enough to capture a barely audible sigh. The video, meanwhile, is so clear that you can read the watch of a person sitting across from you who may be, in reality, thousands of miles away.

Since its debut more than two years ago, Cisco has installed more than 700 TelePresence rooms internally. The technology has been used by Cisco employees to conduct more than 700,000 hours of meetings—almost 80 years worth. Because people don’t travel for these meetings, TelePresence sessions have saved an estimated 228,000 metric tons of carbon emissions and produced an estimated $423 million in travel cost savings for the company.

In addition to saving time and energy, TelePresence systems have helped increase productivity, too. Cisco estimates that the time saved using TelePresence has produced an estimated $122 million in productivity gains for the company.

That said, not all communications require TelePresence. In many settings, the value of virtualizing an experience isn’t so much measured by the audio and video quality of the experience, but rather by the ease and speed at which virtual expertise can be summoned. While TelePresence requires a specifically equipped and available room for all meeting participants, other collaboration tools do not. They can virtualize interactions down to the desktop of every computer in the world. Take the company’s WebEx conferencing technology, for example. With WebEx, meeting participants can simultaneously discuss and edit documents, exchange data, or deliver presentations to virtually any computer in the world.

Expert Scaling

Cisco employs thousands of engineers and salespeople to cater to customers and business partners. Product Sales Specialists (PSSs), in particular, play a significant role. They are the people who answer difficult pre-and-post sales questions from customers and partners deploying Cisco products in a dizzying number of permutations and combinations. They respond to questions about technology and architecture, as well as inquires about upgrade offers, order procedures, installation instructions, engineering support, end-of-sales visibility, purchase approval, and delivery information, just to name a few.

And much like Chambers embraced TelePresence, Cisco’s PSSs have eagerly adopted WebEx to improve not only their productivity, but their quality of life.

Like most companies, Cisco had a long tradition of sending these experts on the road to meet with partners and customers. For eight years, Cisco’s David Farnan was one of those guys. Working approximately 100 miles from the Cisco’s headquarters in San Jose, California, Farnan was schooled in a number of Cisco solutions, including Unified Communications. A typical week would see him meet with two or three business partners, often in different cities, and answer questions from others via email. Mostly, he recalls, he spent a lot of his time driving, filling up his gas tank, and grabbing cheap dinners on the road. “I’d travel four, five, maybe even six hours just to meet with a reseller partner for one or two hours. Then I’d head back to the hotel and respond to emails,” he says.

When Cisco “virtualized” his expertise, Farnan’s productivity went through the roof. He still spends his day attending meetings, sharing his expertise when called upon. Only now he does so from his hometown of Sacramento, California. His tools are his computer, web camera and WebEx. With the help of account managers who transport him virtually into meetings at the very moment he is needed, Farnan answers difficult customer inquires on demand.

The result? A three-fold increase in customer interactions.

But that’s not all. Farnan has reduced his travel so much that he can now do things never before imagined. Thanks to WebEx and other collaboration tools, he won back enough time that he was able to coach the Fair Oaks Pumas, his son’s soccer team in Folsom, California, to a 6-1-2 record in 2008. For his efforts, Farnan was named league “Coach of the Year.”

And he is not alone. Eighty-four percent of salespeople cite positive impact of collaboration technologies. Seventy-eight percent of employees report increased productivity and improved lifestyle.12

Today at Cisco, Virtual Experts like Farnan are common throughout the company. Many have found that their horizons have expanded in ways they never dreamt. If the company’s best Spanish-speaking software expert in the public sector market is located in Spain, for example, then the Latin America team won’t hesitate to include that person in a customer meeting in Argentina. It can all be done at the touch of a button.

Based on the success of these efforts, Cisco expanded its use of collaboration tools in and around the company. One initiative, for example, equipped many of Cisco’s top customers with TelePresence. Another created an online communications and information sharing community for partners around the world.

Thanks to these and other efforts, Cisco can better utilize its global workforce in unprecedented ways. Today, for example, it’s not uncommon for a business expert working in London on a customer issue in Nairobi to turn to Hyderabad for support and to San Jose for insight.

Customer Scaling

Each year, Cisco hosts a number of events for partners, analysts and, of course, customers. But these are finite in terms of attendance, duration, and impact. They can only accommodate so many people, last for so many days, and resonate for so long.

Cisco believes that collaboration technology can reduce these limitations.

Cisco is changing the way it approaches these big events, including product launches and other company announcements. When the time came to announce its entry into the virtualized data center market in 2009, for example, Cisco created a hybrid event that combined the best of the live and virtual worlds. The result?

Despite the unconventional approach, the Cisco Unified Computing System (UCS) launch had more impact than the 2004 launch of the Cisco Carrier Routing System (CRS), which was brought to market in a more traditional fashion. While there were 100 customers present for the live CRS announcement, Cisco leveraged collaboration technology to host more than 7,000 customers when it launched UCS—450 live and 6,600 by TelePresence and WebEx. The launch ultimately generated 4 billion media hits.13

And Cisco did all this for less than 10 percent of the cost of the CRS launch.

The company is also investing in collaboration technologies that allow it to engage with a greater number of attendees at its events. In 2009, for example, Cisco increased participation in its annual Partner Summit by 75 percent when it invited some speakers and attendees to participate from remote locations via TelePresence. It did so at 50 percent of the cost per attendee and earned higher satisfaction scores. And instead of a 3-day conference, the virtual event has become an online community, enabling partners to talk to Cisco and with each other every day.

But this doesn’t stop with big announcements or formal events. It’s something Cisco is doing every day. Take its web site, for example.

“The idea is to create something that would help us ‘sell while we are sleeping,’ providing us additional scale in terms of interactions,” says Sue Bostrom, executive vice president and chief marketing officer at Cisco.

In support of this vision, Cisco has transformed its web site into a model of collaboration by increasing its use of video, blogs, click-to-chat, and other collaboration technologies. As a result, Cisco has seen its web traffic double since 2007. Today, the site attracts nearly 14 million unique visitors per month.

But users aren’t just browsing Cisco’s web site. They are actively engaging with the company and its partners, too. WebEx collaboration tools, for example, not only match potential customers with Cisco resellers, but allow them to interact and share documents. Meanwhile, usage of click-to-chat has skyrocketed. Visitors hold an average of 15 monthly conversations—six times what they did when the technology was introduced two years ago. All of this results in more sales opportunities. Monthly leads generated over the Web doubled from 2008 to 2009.

This success is apparent throughout the industry. Byte Level Research named the Cisco web site one of the top three global web sites in 2010, behind Google and Facebook, but ahead of bellwethers such as Microsoft, Hewlett Packard, and Intel.14

Relevant Again

Cisco transformed itself once when it adopted Internet technology in the 1990s. And it is doing so again today with collaboration. While internal success is well and good, Cisco’s most important metric is how well it enables these business gains for its customers.

No longer the company behind the wiring closet, Cisco is now a trusted partner to numerous companies who look to it as much for the business relevance it can share as for the technological excellence it can provide. That includes some of the world’s most successful companies, including Coca-Cola, General Electric, FedEx, and Procter & Gamble.

More and more, companies like these turn to Cisco for help with expanding into new markets, developing new business models, and, of course, scaling interactions. They do so because they believe that Cisco’s technology and expertise can help them become more relevant to their own customers. Take one of the world’s oldest and most established financial institutions, for example, HSBC. Though nearly a century and a half old, HSBC is one of the world’s most progressive financial institutions. Thanks to technology, the company is able to turn what others would perceive as a liability and use it as an asset. Here’s how the company is doing that, with Cisco’s help.

Relevance in Action: One Customer’s Bold Example

With $146.5 billion in annual sales, HSBC has operations in more than 86 countries and more than 300,000 employees. On any given day, it is the world’s wealthiest financial institution, depending on stock prices and currency rates.

Despite its ubiquity, however, HSBC operates very differently than most of its competitors. Here’s why: HSBC has 8,500 offices worldwide. That’s fewer than some of its rivals have in a single country. In many cities, for example, HSBC customers have to drive past six or seven branches of rivals banks to get to an HSBC office. Competitors are literally more convenient for customers, so HSBC must offer more value.

With the help of Cisco’s IBSG organization, HSBC does this with one of the world’s most advanced IT networks. Rather than invest in brick and mortar facilities, HSBC has put its money toward a powerful information and telecommunications network that gives it a speed and flexibility of which competitors can only dream. Because of this, customers are willing to drive past more conveniently located banks to seek out an HSBC office, where they believe they are better served.

To achieve this level of customer relevance, HSBC has devoted a great deal of resources to technology inside its operations and developed close ties to a handful of companies whose technology is relevant to it.

“We are unabashedly a technology-driven company,” says Ken Harvey, Global Technology & Services Officer at HSBC. For example, fully one-third of the company’s 300,000 workers serve in the HSBC Technology and Services (HTS) business unit, which spends $6 billion annually on IT. That’s roughly 4 percent of revenue—at least twice, if not three times, what comparably-sized companies spend annually on IT.

The Cisco network deployed by HSBC is one of the world’s largest privately owned networks. And given its capability, versatility, and dependability, HSBC literally runs its business on it. Today, the HSBC network carries everything from financial transactions to in-branch entertainment to digital signage information to Voice over IP (VoIP) phone calls to application services for the company. Because HSBC runs a single, converged network, it can offer competitive options that its rivals simply cannot. Take banking transactions, for example. Thanks to the Cisco network, HSBC can prioritize financial trades over other forms of network traffic, such as phone calls or even TelePresence. That capability might not sound much to a layman, but the millisecond advantage it provides translates to billions of dollars each year for HSBC customers. The HSBC platform is so powerful that company executives cite the network as one of the company’s most powerful competitive advantages.

To say that Harvey’s department is aligned with HSBC’s broader business objectives would be an understatement. His organization, for example, has a goal of reducing unit-production costs 10 percent annually. This includes everything from withdrawing money from an ATM to processing a bill payment to completing an equity trade. HTS has accomplished the goal in six of the last seven years and is now pushing other business units to do the same. HTS gets to keep any cost reductions in excess of 10 percent to reinvest in new projects. Harvey, therefore, sees a clear and bidirectional relationship between operational excellence and innovation where each drives the other.

None of this would be possible had the company’s business leaders not foreseen the business value of a world-class technology platform. Consider the bank’s desire to be a more responsible global corporate citizen, for example. Thanks to advances in collaboration and video technology, HSBC was able to replace traditional, printed marketing materials with digital signage—sometimes even personalized digital signage. Not only does the network help the company reduce its carbon footprint, it also helps it provide a level of service that others do not.

In addition to personalized signage, for example, the Cisco network helps HSBC bring more expertise into every banking situation. When a customer request goes beyond the capabilities of a local employee, for example, HSBC simply conferences in a virtual expert to provide video-based support. Experts can be instantly summoned to help anywhere around the world and in virtually any language. For example, HSBC employees can quickly collaborate on an individually tailored product for any customer and email it to the customer before he or she leaves the local branch.

The response has been phenomenal, says Harvey, for both customers, who enjoy better service, and for branch workers. HSBC doesn’t have to train employees in 9,500 locations to be financial experts, just make them adept in how to use simple technology.

Because of its Internet-based business model, HSBC can expand into new markets more quickly than its competitors and ramp up to meet customers’ needs. Take Vietnam and Pakistan, for example. Because of the bank’s use of virtual financial experts and a network platform, it can expand its reach into these markets for less than what others spend on remodeling a local building. In 2007, HSBC began offering credit cards in several countries. The cost to HSBC? Less than $2 million.

“We moved into Vietnam and Pakistan just by expanding our reach through the network. No data centers, no operating centers, no new call centers—nothing. I don’t need to build out that physical infrastructure, which is incredibly costly; everything is delivered through the network,” says Harvey, who credits Cisco for showing the company how to become more relevant to its customers and excellent in its industry.

“There’s only five suppliers that we really allow to use the word ‘partner’ with HSBC,” says Harvey. “We spend $6 billion per year on technology, so a lot of people would probably like to be our partner. But Cisco is one of those few, where we really share a vision and we’ve done some neat things together.”

What this means in business terms, going forward, is increased revenue, reduced complexity, lower operating costs, and higher customer satisfaction. That’s relevance any business leader can understand. Combined with world-class execution, it’s also excellence that rivals dread.

That not only goes for HSBC, but Cisco, too.