Chapter 5. R&D by M&A: Innovation by Acquisition

"Every startup in the world is our R&D lab. If we can't build it, we'll just buy it."

—Telecom Executive in 2000

One way to avoid the potential problems of venturing, licensing, or partnering was simply to acquire innovation—literally. Don't venture to do it yourself and don't mess with the complexities of licensing or the compromises of partnering. Instead, just buy it outright. As companies struggled to hurdle radical technology shifts and juggle greater technological complexity, the idea of acquiring more and more innovation at earlier and earlier stages—even at previously unheard of prices—gained unprecedented appeal. From optics to genomics, so began the great R&D M&A boom.

Never had M&A markets seen anything like the innovation-by-acquisition binge that climaxed in 2000. The inflated stock of acquirers readily financed even richer acquisition purchase prices. At its peak, bankers put together hundreds of technology deals per quarter. Most of these deals remained more traditional buyouts of high-tech companies with real products, revenues, and profits. Increasingly, however, competitors began to bid up and buy more and earlier stage R&D in process. The acquired firms often had little other than unproven technologies or untested prototypes. Sometimes, it was technical talent alone that motivated quick and rich deals.

As with other innovation fads and fashions, however, things turned down as hard and fast as they had shot up. Much heralded, blockbuster innovation deals abruptly turned into spoiled projects and massive, mind-numbing write-downs. Some estimates placed the excess of the entire overall M&A wave at more than $1 trillion. Technology companies topped the roster of record-breaking M&A losses: JDS Uniphase, Nortel, Lucent, and others.

The aftermath of the innovation-by-acquisition binge should not have been completely surprising. Over the years, studies have shown that anywhere from half to two-thirds of M&A deals disappoint and destroy value for their acquirers. Most M&As fail either because the logic for the deal was flawed to begin with, because the price paid was simply too high, or because post-deal integration was bungled. This time around, it would be different, however. It was an entirely new model. Innovation by acquisition had been worked out to a science.

Unfortunately, R&D M&A deals presented their own special problems. The urgency of the go-go technology-driven deals meant rushed bids, higher prices, and limited due diligence. Some buyers didn't fully understand the newfangled intangibles for which they were paying richly. The assets being acquired were not solid businesses with real cash flows. Instead, they were ever-more raw and unproven, and often ephemeral, ideas and technologies. Retaining the acquired firm's top talent therefore was even more critical to making the deals work. But the best and most valuable employees sometimes just walked out the door before the ink on the deal had dried.

Why the Acquisition Boom?

The innovation-by-acquisition boom brought together the cutting edge of high technology and high finance in an especially frothy combination. It was both a cause and an effect of soaring financial markets and of a blossoming multitude of new technologies and new startup companies. The next largest historical wave of M&A in the 1980s had been primarily driven by consolidation and restructuring concerns, usually of mature companies in established or even declining industries. By the mid 1990s, a dramatic change in M&A attitudes got underway: "Companies are being acquired for quick access to scarce talent . . . Some of these buyers couldn't care less about product lines, plants, equipment, or real estate."[1] Many of the targets were VC-funded startups heavy in ideas and talent, but poor in real assets or cash flow. Seeing quick-and-rich exit strategies, they were more than happy to oblige their eager buyers.

For big companies trying to compete with increasingly tech-savvy upstarts, the motto became "If you can't beat 'em, buy 'em." Cisco Systems, among others, claimed that all Silicon Valley was its R&D lab. If you can't (or simply didn't) do the R&D yourself, just purchase it wholesale. The classic "make-or-buy" decision no longer applied just to low value-added nuts and bolts, but to the core of R&D itself. According to the Securities Data Corporation, biotechnology, electronics, IT services, networking, semiconductors, software, and telecommunications became among the most active M&A sectors by the late 1990s. The currency also had changed. The overwhelming majority of these deals were paid for with stock. High equity valuations across the board made even the most high-priced purchases seem relatively painless.

Innovation by Acquisition

The idea of innovation by acquisition was not entirely novel. At least when established industry leaders couldn't outright crush, intimidate, or out-invent them, young and innovative startups had long been favored acquisition targets. Moreover, despite all the outsized attention paid to glitzy public offerings, such as Netscape's huge 1995 IPO, acquisition always had been the predominant exit or liquidity strategy for most startups. Before, during, and after the technology bubble, the vast majority of innovative entrepreneurial firms never came anywhere near a public offering, but rather were acquired.

One 1999 analysis by Broadview International, for example, found that almost 1,900 privately held technology firms had been acquired in the previous year, while only 147 had gone public. This was overwhelmingly true even for VC-backed technology firms. Similarly, data from Venture Economics showed that the total number of venture-backed IPOs plummeted to 35 in 2001 and then only 22 in 2002. But the number of venture-backed firms acquired totaled 336 in 2001 and remained stable through 2002. Valuations were down by 75 percent or more, but a steady and quiet stream of deals continued. At least now the prices were more reasonable.

The New Wave of R&D M&A

What was different about the new New Economy innovation-by-acquisition craze was the number and speed of deals and, especially, the astronomical valuations paid for companies acquired at earlier and earlier stages of development. By contrast, even the most colossal New Economy–Old Economy merger, the ill-fated AOL–Time Warner deal, was more of a traditional M&A transaction than an R&D-driven marriage. AOL was not some small, unknown startup with a newfangled technology. It was the dominant Internet service provider, with tens of millions of customers and a well-established brand name. As superlative and disappointing as the $100 billion plus AOL deal was, it did not necessarily represent radically new M&A thinking, just the incredibly inflated values and expectations of the time.

In contrast, the new wave of innovation acquisitions was distinguished by acquirers who were buying companies primarily or solely for their R&D-in-process or technical talent. Tallies of revenues, profits, and cash flow were of little use in evaluating such deals because the target firms simply had none. New metrics were dreamed up. P/E no longer stood for price-to-earnings ratio. For some R&D M&A deals, P/E instead was shorthand for price-per-engineer. The price could be steep. Deals for companies with little or no sales or tangible assets, much less profits, went as high as $20–25 million or more per engineer, programmer, or scientist.[2] Untested technologies, unproven products, and pure R&D talent itself became more of a primary, if not sole, acquisition objective.

The quantity and value of technology deals soared. According to Securities Data Corporation, the number of software acquisitions grew from fewer than 100 deals in 1985 to more than 1,100 deals by 1998. The growth was not simply a function of the general boom in M&A activity during the same period, either. Software M&A rose dramatically as a proportion of total deals, from approximately 3 percent in 1985 to more than 14 percent by 1998. Then, the innovation-by-acquisition spree really got started.

Cisco the Serial Acquirer

No company exemplified the innovation-by-acquisition trend more than Cisco Systems. During the 1990s, Cisco grew phenomenally. By the end of the decade, for a very brief period, Cisco peaked as the most valuable company in the world in terms of market capitalization, besting even Microsoft, at more than half a trillion dollars. The Cisco growth story was fueled by an accelerating series of acquisitions, both big and small.

Cisco's roster of deals began in 1993 with its $90 million purchase of Crescendo Communications. Within just a few years, the technologies and products at the heart of the Crescendo acquisition would become Cisco's largest single business. Throughout the 1990s, Cisco acquired dozens more young companies, for everything from software to hardware, to fill out its technology and product portfolio:

No company typifies the new world of M&A better than Cisco Systems. To understand how it has built its empire, it is necessary to forget all that one knows about corporate raiders and their swashbuckling tactics. Disregard the stereotypes of ruthless capitalist villains aiming to gobble up corporate America's finest . . . Think of Cisco as an acquisition engine, as cleverly designed and highly tuned as the giant routers it builds to handle vast surges of Internet traffic. Like those routers, the acquisition engine runs on Internet time. In the past 6 years, Cisco has spent $18.8 billion on 42 acquisitions. It prowls Silicon Valley—and the world—snapping up companies to expand existing product lines or support entirely new initiatives.[3]

Cisco set the trend and the pace. Its ever-upward stock seemed to be a limitless currency with which to do deals, creating a virtuous cycle.

Over time, Cisco's own acquisition strategy evolved. The networking leader began to acquire younger new startups at earlier and earlier stages of development. By the end of the 1990s, it had switched from acquiring up-and-coming companies with fantastic new products and booming sales to acquiring more and more R&D in process. By 1999 and into 2000, the process shifted into overdrive. Cisco was acquiring a new company every few weeks. Purchase prices soared. An entire gaggle of high-tech startups came into being with the specific hope and plan to be a quick and rich Cisco deal.

After just seven years, by the peak of the market bubble in March 2000, Cisco had acquired 52 companies. The tab totaled more than $20 billion, but it seemed to be more than worth the price. Cisco undisputedly was the world leader in the lucrative, can't-build-it-fast-enough hardware that powered the Internet. Cisco became the model to emulate. Many subsequently did try to imitate Cisco and even exceed its acquisitive zeal.

Not that Cisco was easy to top. Cerent was the deal that certified the beginning of a new era. Cerent was a hot new optical Internet router maker preparing to go public in mid 1999. Cisco was strong in electronics, but relatively weak in optical technology. The entire telecom and Internet world seemed destined to go optical, however, and optical was Cerent's strength. Cisco already owned 8 percent of the startup from an earlier, exploratory investment. In August 1999, Cisco pre-empted Cerent's IPO and offered a jaw-dropping $7 billion in stock to buy the rest of the company outright.

The rich price was literally unprecedented. Cisco's previously highest-priced deal, $4 billion for StrataCom in 1996, had bought it a profitable company of 1,000 employees with more than $300 million in revenues. In contrast, Cerent had fewer than 300 employees, just $10 million in revenues, and a loss of $29 million for 1999 to date. All the value was in Cerent's potential; there was little else by which to value it. Using one of the novel M&A metrics of the time, some noted that the deal cost Cisco almost $25 million per employee. Cerent's owners certainly were happy. Only a month earlier, the company had announced its plans for a public offering to raise just $100 million.

Changing R&D Paradigms

The new innovation-by-acquisition approach contrasted significantly with the old R&D design. This contrast could be seen clearly by comparing Cisco's evolution with that of Lucent Technologies. Over the decades, Lucent had nurtured its Bell Labs into a Nobel Prize-winning nurturer of all kinds of scientific and technical talent. Through its lucrative telephone monopoly, AT&T (Lucent's parent until 1996) steadily and handsomely funded Bell Labs.

By the time of Lucent's spin off, however, the telecom marketplace had already begun to be much more fiercely competitive and much more fast-moving and complex on the operating and technical side. The old scholarly, gentlemanly approach to R&D increasingly seemed to be a bygone luxury. New up-and-coming engineers dreamed less of building a career at Bell Labs and more of joining a hot new technology startup. Making the situation even more complex, traditional telecom and the Internet began to blur. The old, safe and steady business of selling gear to established long-distance providers and local telephone monopolies started to turn into a scramble to provide better and faster technologies to both new and old telecom and networking companies alike.

But Lucent initially resisted joining in the innovation-by-acquisition frenzy. The company had a long and distinguished history of world-class internal R&D excellence and a strongly inward-focused engineering culture. In practical terms, Lucent's reluctance to deal also stemmed from pooling-of-interest restrictions related to its spinoff from AT&T. Any big acquisition purchases would take a big bite directly out of Lucent's financials. These accounting constraints expired late in 1998, however, letting Lucent more freely consider its options.

Meanwhile, the pressure on Lucent had grown. Telecom giant Alcatel had acquired networker DSC Communications in mid 1998 for $4.4 billion. In a similar move, Northern Telecom acquired Bay Networks for more than $9 billion, even changing its name to Nortel Networks in the process. Newly freed from its accounting chains, Lucent finally signaled that it would not be left behind the dawning digital age. The stakes were high. In December 1998, Lucent acquired networker Ascend Communications for more than $20 billion. The big deals seemed strategically sound, even if they were increasingly somewhat pricey. They brought not only new R&D and technology to their acquirers, but also substantial revenues and customers from already well-established networking industry leaders. They were just warm-ups for the deal sprint about to begin.

Cisco's Cerent acquisition in August 1999 was the starting gun. Technological and competitive urgency grew, and the relative pace and size of deals soared. The science of R&D and the art of the deal, the mysterious alchemy of technology and finance, became increasingly intertwined. It was not always clear which drove which.

Network equipment startup Siara Systems had yet to test a product in November 1999, but Redback Networks offered $4.7 billion for it nonetheless.[4] Privately held optical transmission startup Qtera did not yet have a product on the market; Nortel paid $3.25 billion for it in December 1999. Nortel added to its string of deals in March 2000 with its acquisition of Xros, a photonics switching company also with no revenue or product shipped, also for $3.25 billion. Responding in kind, Lucent acquired fiber equipment maker Chromatis in May 2000. Chromatis was just two years old and had not yet shipped a single product. Lucent offered $4.75 billion. Quickly, Cisco and the old-line telecom manufacturers started to look much more alike, in more ways than one.

In a world of supposedly rational and efficient markets, executives, analysts, and academics alike scrambled for new justifications for such stratospheric deal valuations. The old rules no longer applied. Valuation seemed to become storytelling and cheerleading as much as science. The only justification needed for some high deal prices was a "comp" (comparable), meaning an astronomical price became justified simply because someone else, for whatever reason, might be willing to pay as much or more. Was it all really worth it?

Need for Speed, Technology, and Talent

The need for speed was probably the most often-cited deal driver and a key justification for high prices. In the fast-moving, hypercompetitive New Economy, the dominant view was that, in so many new and rapidly transforming industries, the window of opportunity wouldn't remain open for long. It wasn't just for telecom and the Internet. It was also in biotech, semiconductors, and any number of other sectors. Tomorrow wasn't good enough. Companies felt the compelling need for the latest-and-greatest technology today.

Internally, acquirers couldn't do R&D fast enough, no matter how much money they were willing and able to throw at a problem. Even if Cisco Systems were willing and able to spend $7 billion R&D to try to develop its own optical routers, for example, the feeling (both inside and outside the company) was that it would simply take too long. It was faster to buy R&D in process from Cerent than to try to assemble and build a technical team from scratch. First to product and market, if not the only thing, was usually at least a compelling goal. Certainly, at least being fast to market, even if not first, was essential. The perceived need for R&D speed fit perfectly with the larger, pervasive creed of first-mover advantage.

If companies didn't have enough urgency themselves, they were pushed to get technologically acquisitive by analysts and investors. The rewards and punishments dealt by the financial markets were contrary to their reactions in more traditional M&A deals. The stocks of companies doing R&D acquisition deals, even at exorbitant prices, got pushed higher. Stocks of companies that hesitated or refused stalled or were even punished. It became easy to make the self-justifying argument that the absence of a blockbuster R&D deal could easily lop billions or more off a company's market capitalization. Analysts and investors would turn their backs and bail on such technological laggards—the ones that "just didn't get it."

Rich deal prices also seemed unavoidable in a context of grossly overvalued (technology) stocks in general. It was better to buy a privately held startup quickly and now, even for billions, than to potentially face a bidding war later and pay billions more, or to pay even greater sums after a company went public. This calculus was not pure speculation. Networking, optical, and other technology companies that did go public during this era quickly reached valuations in the billions (for example, JDS Uniphase and Juniper Networks).

Dozens of innovation-by-acquisition deals were done quickly and richly specifically to preempt the need for even richer post-IPO transactions. The need for speed rapidly became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Leading companies quickly snapped up any and all potential technology targets. If you didn't act fast, there might not be anything left. This pressure was most extreme in telecom and networking, but it quickly grew to encompass almost any sector in which radical new technologies and unique technical talents were at a premium: software and semiconductors, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology and bioinformatics, and so on.

Radical Technologies and Unique Talents

What powered many of the highest-value, highest-profile deals was the New Economy–Old Economy divide. Beginning in the mid 1990s, for example, Monsanto and DuPont bid against each other and spent billions to acquire a series of agricultural biotechnology concerns at ever-higher prices. Both chemical giants attempted to leap from commodity chemicals into a brave new world of more lucrative, genetically engineered bioscience. Likewise, telecom manufacturers tried to conquer the new world of networking, and electronics firms tried to make the leap to new optical technologies. They faced fundamentally altered technical challenges and befuddling new business models. Meanwhile, traditional, trial-and-error, chemical-focused pharmaceutical firms confronted an entirely new array of high-throughput screening, targeted genomics, and biotechnology-generated proteins. Their decades of accumulated drug-discovery knowledge suddenly seemed much less relevant, even antiquated. In contrast, their acquisition targets appeared to have mastered these radical new technologies. They also had the world-class, one-of-a-kind brainpower and technical wizardry needed to continue to further develop and deploy them.

Sometimes, talent alone was a critical objective:

[E]ngineers and scientists are still in high demand, so much so that semiconductor and optical networking outfits are doing more of what bankers call HR deals (HR for Human Resources). In these acquisitions the employees are seen as more valuable than the company's product.[5]

The battle for technical talent even spawned a new valuation calculus:

[I]t's human capital companies are after. A potential target's value is determined by the number of engineers it employs and their skill set.[6]

Talent markets grew tight. Salaries, stock options, and benefits soared. Deals at $2 million per employee that had raised eyebrows in 1997 soon were eclipsed by $20 million per employee deals just two or three years later. The intensifying competition for talent meant that retaining the services of increasingly scarce knowledge workers—innovators such as top programmers, engineers, and scientists, as well as creative types—required buying entire companies. It was not enough to pick up a few engineers here and there. M&A was the only way to get enough good talent quickly.

Once again, Cisco helped set the tone. Cisco's attention to the details of implementation, especially talent retention, was thought to be key to its many acquisition successes. It wasn't always a completely smooth process, but Cisco tried to learn from its early acquisition stumbles. Subsequently, the company had instituted a more detailed plan and process for integration.

CEO John Chambers noted that most of what Cisco was doing was acquiring people. It placed great emphasis on keeping acquired employees happy to retain their skills long after the acquisition deal was done. The company was frequently featured as unusually successful at retaining key acquired employees—at least more so than most acquirers. Cisco gave them generous option grants, communicated openly and frequently during the acquisition process to reduce uncertainty, and rapidly integrated them into important roles within the overall Cisco team and culture. Most firms did not seem to pay nearly as much attention to these "softer" issues and did not address them with such forethought. When paying millions of dollars per employee in an ongoing war for talent, acquiring and retaining key employees was not a "soft" or trivial issue.[7] It was central to the task of innovation.

The Deal-Making Denouement

Overall M&A activity reached historic heights in 1999 and 2000, with over $3 trillion in deals globally each year. Just a year later, the total value of M&A deals dropped to about a third of those levels; the number of deals dropped less, but still dramatically. Stock had been the boom-time currency of choice. Now, cash was king again as the majority of sellers demanded hard currency. As the general M&A boom went bust, so did innovation by acquisition. Frenetic, high-priced R&D M&A deals abruptly disappeared.

Again, except this time on the downside, Cisco set the pace. In 1999, Cisco bought 30 companies. By 2000, the number dropped to 11. For all 2001, Cisco acquired just two companies: Allegro Technologies and AuroraNetics. Cisco slowed its gusher M&A pipeline to a trickle. Amid the crumbling of the telecom sector and the sputtering of the networking business, Cisco retrenched, laid off, and downsized. The company decided to focus more on tapping the internal brainpower and invention of its own thousands of engineers and to rely less on acquisitions. It was a sea-change in strategy, an apparently radical break from its own innovation-by-acquisition legacy.[8] Even Mike Volpi, the celebrated strategist and deal maker for most of Cisco's serial acquisitions, transitioned to a different, daily, operating role as senior vice president of Cisco's routing technology group.

The frenzied deal-making days were clearly over. In retrospect, there was consensus both within and outside the company that Cisco's later acquisitions especially had not been nearly as successful as they had initially appeared. The technology and products were more problematic, the integration less smooth, and the added growth much less than hoped and planned. As it surfed the massive wave of Internet growth, most anything fast-growing Cisco did would have seemed brilliant. Now, for both itself and other would-be imitators, Cisco's innovation-by-acquisition success during the 1990s seemed much more an exceptional historical episode rather than a durable new model for innovation. Moreover, in practical terms, Cisco's stock no longer was the "better than gold" currency that it had been.

The giddy deal-making days ended. Proponents of any new Cisco acquisitions would be held responsible to commit to their financial results, not just hype a great new technology. Even Cisco's March 2003 acquisition of Linksys for $500 million, its most expensive purchase since 2000, was a return to a more grounded type of M&A deal. Linksys was already the leader in home wireless-networking gear; it was not a quick speculative bet on unproven technology or raw talent. Linksys was an established company with proven products and real revenue. With sales of $430 million in 2002, Linksys commanded a very modest price of just a little more than one times revenue.

Hangover from an R&D M&A Binge

The aftermath of the R&D M&A boom and bust is surprisingly difficult to assess clearly and objectively. Even in hindsight, it's difficult to get meaningful agreement among entrepreneurs, executives, analysts, or academics on which deals made sense and which did not, how much the rich prices were justified and necessary, or whether they simply represented the height of the irrational exuberance of the times. Even well after the fact, great disagreement exists about the logic and performance of many of the priciest, high-profile deals. In the telecom and networking sectors, for example, there is no control group with which to compare non-acquirers and aggressive acquirers; almost all the leading firms actively participated in the innovation-by-acquisition binge and at extremely high prices.

It's also not easy to pick an agreeable metric. Does the fact that the stock of a Cisco, Lucent, Nortel, or JDS Uniphase was itself fantastically overvalued excuse the fact that these companies' acquisition deals were even more overpriced? Does the fact that some of these acquisitions did not pan out and were simply shuttered reflect a massively failed innovation strategy or instead just reflect the inherently uncertain and risky nature of R&D and innovation in general?

Goodwill Gone Bad

One way to assess the aftermath, of course, is to examine the numbers. Accounting complexities and other convenient justifications aside, goodwill write downs in the aftermath of M&A deals more often than not are an implicit admission that a buyer simply paid too much for acquired assets. What remains of the acquired firm is worth less than the purchase price.[9] In this regard at least, the bottom line (literally) was that record-setting innovation-driven M&A deals quickly were transformed into record-setting write downs and losses.

In 2001, for example, fiber-optic components maker JDS Uniphase took more than $50 billion in goodwill write downs, most of which reflected the devaluation of its high-priced acquisitions. The total was the largest asset impairment charge in U.S. corporate history. Dramatic reductions in the value of three 2000 acquisitions in particular—its $41 billion purchase of SDL, its $18 billion transaction for E-Tek Dynamics, and its $2.8 billion deal for Optical Coating Laboratory—accounted for most of the losses. Obviously, some observers thought the losses indicated that JDS Uniphase's acquisition strategy had seriously stumbled. Others disagreed, including management:

From [JDS CFO] Muller's perspective, however, the acquisitions JDS made during the capital spending Brigadoon firmed its position as a leading fiber optic component maker, and the mountain of goodwill the company accrued in doing so was justifiable. The employee talent and technologies JDS garnered were invaluable, and if Muller knew then what he knows now, he wouldn't change a thing.[10]

Some outsiders agreed. The $50 billion write down and massive losses were meaningless. They were purely cosmetic, even if they were nominally as large as the entire GDP of New Zealand. It didn't really matter; it was not real money. It was simply an accounting charge, a formality to comply with new bookkeeping rules, with no real cash flow implications. Ignore it.

Cash or Stock: Play Money?

This perspective raises some curious questions. How can a $50 billion loss not be a reflection of a problem, in some way, at some point? If accounting-based performance measures are meaningless, by which metrics should performance be measured? Did having paid in (especially inflated) stock, rather than cash, make even overpriced acquisitions not really a problem? After all, no "real" money was exchanged or lost.

The problem with this logic is that stock is not play money. It has real value—including real cash value—that begs to be taken more seriously. Ultimately, $1 of stock equals $1 of value, regardless of accounting complexities and other justifications. Opportunity cost considerations make the assessment even more complex. What else could a company have bought? Or could acquirers simply have waited and then acquired the same companies for a fraction of their original asking price, after valuations had plummeted? Of course, by then the buyers' own stocks had plummeted as well, dropping their shares 90 percent or more in some cases. Cash prices might have dropped precipitously, but the number of shares required to purchase the same company might have been even greater than before. With such strange deal-making math, it's a bit easier to explain, if not excuse, at least some key aspects of the stock-fueled M&A mania.

Not all these acquisitions were paid for in inflated stock, however. Cash deals make the hit from disappointing acquisitions seem more real, even if theoretically no difference between stock and cash exists. Corning, for example, acquired Pirelli's optical components business in December 2000, paying $3.6 billion in cash. In early 2001, however, Corning took more than $3 billion in charges to reflect a severe decline in the acquired assets' value. In just months, most of the deal's cash purchase price had evaporated. Corning claimed that this did not mean they had overpaid for the acquisition, but rather simply reflected the fact that telecom markets had turned down suddenly and dramatically. Whatever the explanation, the loss was just as big.

In the aftermath of the innovation-by-acquisition deflation, Cisco Systems CEO John Chambers expressed the now more sober deal-making calculus. Whether stock or cash, he stressed, it was ultimately the same deal. Both came out of shareholders' pockets, either from the firm's cash reserves or as diluted shares. Deal-making shares probably would be paid off in cash eventually anyway, with share buybacks necessary to reduce shareholder dilution. Times and attitudes clearly had changed; the pendulum had swung back toward more grounded M&A attitudes. The need for speed, technology, and talent no longer justified acquiring innovation at any cost.

Addicted to Speed

Apart from the problem of greatly inflated prices, was the underlying logic of innovation by acquisition (especially R&D by M&A) still sound? The need for speed, technology, and talent seemed a compelling trio of innovation motives and objectives. Did the R&D M&A boom still more fundamentally represent a significant and sustained shift toward a new paradigm for innovation, as so many of its proponents had proclaimed? Or was it just another temporary craze, like much of the rest of the technology and market mania of the time? Perhaps it was a bit of both.

For example, was the "need for speed" a sound logic for such quick-and-rich deals in the first place? Certainly in hindsight, the urgency seemed overdone. Even in many new and fast-growing industries, being the first or fastest tends to be an overrated success factor.[11] Moreover, the need for speed always comes with a price. Urgency costs in more ways than one. It means doing deals earlier, when technologies and markets are more embryonic and far from certain bets. Getting a deal done now also requires paying whatever the seller or market demands; impatience inherently tends to raise the price.

Urgency also raises the likely cost of a deal because of the fact that there is simply less time for due diligence. During the height of the boom, multibillion-dollar deals were sometimes negotiated in just a few hours. Rushed due diligence raises the likelihood and magnitude of mispricing and other mistakes (such as buying a dud). In some cases, buyers didn't quite understand what they were buying at such rich prices; the acquired firm's radically new, different, and unfamiliar technology was what motivated most of the deals in the first place. With such dynamics in play, sellers can pitch a "lemon" and fetch a good price; sometimes, they did just that. All these issues characterized the R&D M&A binge and all played a role in the many subsequent disappointments.

If speed really were the prime success factor in most cases of innovation, it nonetheless might be worth the price and risk to engage in even expensive and uncertain R&D deals. But first-mover advantages often are more myth than reality.[12] Pioneers help pave the way for others, but the first companies to jump in a new technology or market more often fade or eventually fail. Meanwhile, strong followers gain and then maintain lasting technology and industry leadership. Slow and steady often does win the race. Even if being early is better—all things being equal—being the pioneer may not be the "crown jewel" that some companies seem willing to pay so much for. Execution speed is good, but more speed isn't necessarily always better.

Big Bucks, Little Results?

Even if being first or fastest wasn't essential, surely acquiring brand-new technologies and capabilities was worth doing many deals. In some cases, it was. Yet, with a number of R&D M&A, little was left to show for huge sums spent. In less than two years, Nortel simply shut down the division it had formed with its $3.25 billion acquisition of Xros. Xros's technology for making an all-optical switch did not work as planned, was difficult to manufacture, and the optical market never materialized as anticipated. Similarly, less than a couple years after Nortel paid $3.25 billion for Qtera, the key technology and product that motivated the acquisition had simply faded away. Nortel's write downs for these and other deals totaled more than $12 billion in 2001. Nortel was far from alone. Lucent discontinued Chromatis's products in 2001 and took a nearly $4 billion write down as a result.

Even Cisco Systems, the master acquirer, was not immune to these risks. Cisco paid $500 million for Monterey Networks in August 1999. Monterey was developing optical networking routers, but did not yet have a fully developed product. Cisco hoped to bolster its own nascent optical networking business. After 18 months of technical problems, delays, and disappointing sales, however, in April 2001 Cisco announced that it would stop making the routers. The Monterey-based offerings disappeared. Neither the technology and product, nor the market itself, had worked out as planned. Unlike many of its peers, Cisco had long since chosen to expense, on an ongoing basis, most of the price of its acquisitions as in-process R&D. As a result, Cisco avoided a long list of its own goodwill write downs and losses.

These experiences highlight some of the key tradeoffs and dilemmas of innovation by acquisition, especially early-stage R&D M&A. Acquirers are making a bet. Much of the uncertainty and risk remains. Paying a rich, speculative price for a relatively early stage deal exacerbates these risks. In the aftermath of the R&D M&A wave, more sober valuations for these types of deals reflected a turn back toward a fundamental economic truth: Risk should be discounted, not inflated. Moreover, no matter how intrinsically valuable, even successful technology can never be truly profitable if its price is simply too high to begin with.

The Slippery Logic of Acquiring Talent

Acquiring top-notch, world-class technical and creative talent by itself sometimes seemed a compelling acquisition objective. But purchasing a firm does not equate to having retained the continued services (the loyalty, creativity, and productivity) of the acquired firm's top talent. Yet, this was a key presumption of many innovation-by-acquisition deals. It's entirely possible that much of the high-priced, high-potential talent will simply walk away soon after a deal is done.[13] With a change of control, turnover of key employees typically skyrockets. More unfortunately, top talent often leaves first; the best employees are obviously the ones with the greatest opportunities elsewhere. This is a common dilemma when companies aim to acquire top talent (such as entrepreneurs, engineers, scientists, programmers, artists and designers, project managers, and other key employees). A rich, high-premium deal price might end up buying little more than a hollow shell of a company with few people left to make things work.

Even Cisco, with a much better record of employee retention than most, had issues with turnover of acquired talent. Cisco's overall post-acquisition turnover rates might have been relatively low. But combing the record reveals some retention problems nonetheless:

[Cisco CEO] Chambers often maintained that his acquisition strategy was aimed at acquiring brainpower more than products. But an analysis of the 18 acquisitions Cisco made in 1999 shows that Monterey was no fluke. Many of the most valuable employees, the highly driven founders and chief executives of these acquired companies, have since bolted, taking with them a good deal of the expertise and experience for which Cisco paid top dollar.

The two founders of StratumOne Communications Inc., a maker of optical semiconductors purchased for $435 million, left Cisco. The chief exec of GeoTel Communications Corp., a call-routing outfit acquired for $2 billion, walked out after nine months. So did the CEOs or founders of Sentient Networks, MaxComm Technologies, WebLine Communications, Tasmania Network Systems, Aironet Wireless Communications, V-Bits, and Worldwide Data Systems—all high-priced acquisitions in 1999. Some simply felt Cisco had become too big and too slow. "People who crave risk don't do so well at Cisco," says Narad Networks CEO Dev Gupta, who sold Dagaz and MaxComm Technologies Inc. to Cisco in 1997 and 1999, respectively. "Cisco focuses much more on immediate customer needs, less on high-wire technology development that customers may want two to three years out."

. . . After losing many of the leaders of these businesses, product delays and other mishaps were not uncommon. When Cisco closed down Monterey, for example, the company still hadn't put a product out for testing, which alone would take as long as a full year. "By the time the product was there to test, the market wasn't," says Joseph Bass, former CEO of Monterey.[14]

Another unfortunate M&A dysfunction was discord and discontent among existing Cisco employees. Some of the newly rich, newly acquired Cisco employees adopted a "new kids on the block" swagger, causing ill will among incumbent engineers who had toiled with Cisco for years, and whose own stock and options soon withered in value. Not only acquired talent left, but existing Cisco talent also departed.

Golden Handcuffs for Free Agents?

Most strategies to try to reduce or eliminate post-acquisition turnover of top talent have limited effectiveness at best. So-called "golden handcuffs"—the idea of bribing top talent in the acquired firm to stay after an M&A deal is done—are a nice metaphor. But they usually don't have the desired effect. In one study of a large number of hi-tech, talent-driven acquisitions in a wide variety of industries, the results revealed much: Across the board, golden handcuffs failed at a high rate. Neither restricted nor unrestricted stock options or grants, nor long-term contracts with cash and other bonuses, had significantly positive effects on retention of key employees.[15]

This was a recurring and significant problem for a large number of the more than 100 cases of innovation by acquisition we examined. One high-tech engineer/entrepreneur summed it up, "I had my desk packed before the ink [on the deal] was even dry." The deal itself had rewarded him quite well. Flush and comfortable, he already was on his way to thinking about the next startup opportunity, not about how to serve the new corporate master.

Talented Competition: Palm Versus Handspring

The saga of Palm versus Handspring illustrates well the tensions inherent in trying to acquire and retain top innovators. Here's the typical scenario: Acquired innovators uncomfortable with serving their new corporate masters yearn to break free. Instead of staying put, the top technical and entrepreneurial founders bolt, found a new firm, and sometimes even end up competing with their former masters. This was Handspring's story.

Donna Dubinsky and Jeff Hawkins founded Palm, the pioneering maker of personal digital assistants (PDAs). With their PDA product still in development and starved for cash, Palm needed assistance. U.S. Robotics, the leading modem supplier, came to the rescue and acquired Palm for $44 million. Apple's Newton might have come earlier (perhaps too early), but Palm became the first successful PDA. Unlike many earlier and clunkier concepts, Palm's PDA easily linked and synched with a standard PC. In 1997, more than one million Palm Pilots shipped. Palm was an unqualified success, literally the stuff of Silicon Valley legend.

Events took another turn, however, as 3Com acquired U.S. Robotics. Dubinsky and Hawkins pushed 3Com to spin out Palm and let it be free. They felt that the Palm concept and its potential would get shortchanged and suboptimized. Palm now was trapped within the confines of an even larger muddling-and-meddling corporate parent more concerned about cost-cutting and maintaining margins than growing an exciting new business.

3Com refused to let Palm go, so Dubinsky and Hawkins quit and hired a team of their own engineers. Venture capitalists (VCs) salivated and fought each other for the privilege of funding the duo's new company. Within a year, the Handspring Visor PDA was born. The Visor was a lower-cost "clone" of the Palm PDA, using the same operating system (licensed from Palm). Handspring innovated a step further by adding expansion-slot capabilities that allowed its PDA to become an MP3 player, phone, digital camera, and whatever else could be dreamed up and plugged in. It quickly captured almost one-third of the PDA market. Capping off this success, Handspring went public in mid 2000. Ironically, this was just three months after 3Com finally decided to spin out Palm after all, with its own IPO.

The Palm and Handspring rivalry grew. Competition turned to price wars, followed by big losses and layoffs for both players. Palm struggled, and Handspring itself was running short of cash. In 2003, completing the complicated saga, Palm agreed to acquire Handspring.[16] After battling each other for years, together again they finally would try to better compete against the new and rapidly proliferating mobile computing rivals (e.g., Microsoft-based and cell phone–based systems).

The Palm-Handspring saga is not an odd exception. Much top talent tends to leave in the wake of an acquisition; the best are most likely to leave, and likely to leave the fastest. Moreover, top teams tend to stick together—including when they leave. Golden handcuffs offer limited hope at best. Even when they reduce turnover, they still cannot buy top talent's loyalty, productivity, or creativity—the key intangibles that make the difference between success and failure. Overemphasis of non-compete agreements also misses the key point. Most acquired top talent doesn't necessarily leave to start a direct new competitor—although it does happen, and even despite non-compete agreements. Regardless, with significant post-deal turnover, top talent—and all their knowledge, skills, and relationships—might be lost either way.

Buying Innovation Still Can Be a Good Deal

As the previous examples highlight, innovation by acquisition has its own unique costs and risks. Despite these inherent dilemmas and formidable challenges, the M&A approach nonetheless represents a useful evolution (though not revolution) in the concept and practice of innovation strategy. Acquiring fast-growing technology companies with hot new products was not a new idea. What was relatively novel was the idea of acquiring more and earlier-stage R&D in process (R&D by M&A). In the aftermath of overzealous deal making, both early stage and later stage innovation deals assumed a more sober yet still important role in the innovation mix. But it also remains true that neither is a cheap and quick fix for core technology and talent needs.

When does innovation by acquisition make sense, and when is it worth the price? Many lessons can be learned by reflecting on the R&D M&A boom and bust. The excesses and errors of the period had less to do with a fatal flaw in the idea itself and instead had more to do with problems in its application and execution. Acquisitions were rushed because of a too-urgent "need for speed" to gain hot new technologies and capabilities. Hurried and limited due diligence in turn led to both too-high prices and high-priced duds and lemons. Overall frothiness in the financial markets did jack up the prices. But too-high deal prices also were a result of flawed risk/reward discounting and fanciful valuation justifications. Ultimately, the considerable risks of paying richly for unproven new technologies, uncertain new markets, and fickle new talent were neither anticipated nor managed well. All these issues need to be (and fortunately can be) better tackled in contemplating, valuing, and executing innovation-driven acquisitions.

Bargain Shopping: Balancing Risk and Reward

These issues are especially critical in earlier stage deals (R&D M&A). The fundamental differences between early stage and later stage deals got blurred in the M&A frenzy. Early stage and later stage deals need to be evaluated, paid for, and planned for differently. Risks and rewards need to be balanced. Early stage R&D M&A deals can be sensible and fruitful bets to try to gain the potential of brand new talent, new patents, and new products and processes, for example. The farther they are from commercialization, however, the more the inherent uncertainty and risk should discount their value. R&D M&A deals also need to be adjusted accordingly to the degree that the target innovations depend on potentially fleeting intangibles, including talent itself.

The bottom line is that early stage R&D deals should be appropriately discounted, not inflated. Only then is risk properly compensated and, if the bet is successful, only then are the rich potential profits not already squandered at the moment of purchase. Moreover, bargains can be found for both early stage (R&D) and late stage innovations. Paradoxically, bargains abound most when, and largely because, buyers are scarce.

The irony is that many companies hesitated to do early stage R&D M&A deals just as prices for some valuable technology and talent was coming back into more reasonable (even bargain) price ranges. The result of this reluctance was foregone opportunities.

For those with the courage and cash, deals abounded. The valuations of VC-backed technology firms, in everything from biotechnology to semiconductors, tanked by 75 percent or more from 2000 to 2002. In some sectors, the discounts approached 90 percent. Moreover, with VCs stingy and with the IPO markets dried up, technology startups now were willing to settle for more agreeable purchase prices. The fundamental value of the startups' underlying technologies, ideas, and other assets had not changed in most cases. Only now they could be had for a fraction of their previous prices. According to Venture Economics, smart buyers kept the volume of VC-backed acquisition deals fairly constant from 2000 to 2002, even as average prices plummeted. Deals that formerly looked too big and risky suddenly looked like more reasonable bets.

Buyers snatched up high-quality biotech and genomics and software and semiconductor startups for anywhere from 10–50 cents on the dollar compared to valuations just a short while earlier. Johnson & Johnson acquired drug-discovery company 3-D Pharmaceutical for $88 million in late 2002, for example. Even though 3-D now had more time-tested science and drug discovery in progress, just a couple years earlier its less mature R&D easily could have cost Johnson & Johnson two or three times as much. Not that the risk and uncertainty of R&D by M&A was gone by any means, but the risk/reward ratio seemed slightly more rational.

Similarly, to help fill out its wireless technology and product portfolio, RF Micro Devices acquired privately held semiconductor startups RF Nitro and Resonext in late 2001 and 2002, respectively. Despite being a far from certain bet, Resonext did already have some products and customers. RF Nitro's technology was an even earlier-stage bet, but promised potentially radical performance improvements in semiconductor technology. Neither purchase was a fire-sale bargain. Even in a down overall market, wireless remained a relatively hot sector. Still, the startups' price tags seemed more reasonable at about $1.9 million per engineer instead of the peak M&A technology market prices of $19 million or more per engineer (that is, if anyone still gave any credence to such curious metrics).

In 2004, Cisco itself aggressively re-entered the innovation-by-acquisition game with a renewed—though also much recalibrated—strategy. Shopping around for new technologies and new markets was back in style, yet the terms differed this time around. Prices for hot young startups with the promise of great new things ran more in the $80 million, rather than $8 billion, range. Talk about relative bargains: Venture capitalists had plowed more than $250 million into Procket Networks's R&D since 1999, but Cisco paid just $89 million (in cash, not stock) for the assets of the core router hardware and software maker in June 2004. A month later, Cisco paid just $9 million for control of Parc Technologies, a networking technology startup whose earlier second-round of venture funding had totaled $23 million.

With due diligence—at the right price and with the right risk/reward ratio—and with a good plan for integration, acquiring even uncertain, early stage R&D or potentially fickle innovation talent can still be a reasonable, and sometimes even an exceptional, bet. In contrast, later stage, more product-driven acquisitions (post-commercialization) offer a different, less uncertain proposition. In either case, however, smart deals can be done.

A Durable Part of a Core Innovation Strategy

The excesses and errors of the innovation-by-acquisition binge must not be allowed to obscure the fact that many companies have been able to use innovation acquisitions in a successful and sustainable fashion. In most of these cases, M&A have functioned not primarily as substitutes or replacements for core innovation, but rather as a unique means to renew, supplement, or reorient a firm's innovation focus in a steady and measured way. To this end, innovation by acquisition offers possibilities that the other innovation modes (venturing, licensing, and partnering) cannot match. Beyond any existing products or assets that might be purchased, only M&A can bring a rich new mix of high-potential talent and technologies directly to an acquirer. The great potential value can only be realized, of course, if due diligence is done well, if the price is right, and if the talent and technology can be integrated successfully.[17] These remain the core challenges.

Even while Cisco received most of the attention, for example, IBM more quietly used M&A to transform its innovation focus. In a relatively gradual but significant series of acquisitions, IBM successfully reoriented toward less reliance on hardware and greater competence in software and services. IBM did not abandon its prolific hardware competencies. Instead, its string of software and services acquisitions helped supplement, and shift over time, the innovation center-of-gravity of the entire company. The acquired companies tended to be up-and-coming leaders in software and services, already with proven technologies and significant and growing sales. They brought with them more than just products. They also brought a potential fountain of new talent and technologies. In regard to one key acquisition, for example, "The union of IBM and systems management company Tivoli Systems...has surprised skeptics. Rather than seeing its innovation crushed by IBM's once-domineering corporate culture . . . Tivoli took the development reins."[18] This was a recurring pattern. Cumulatively, and with the complementary realignment of its own internal R&D initiatives, IBM's acquisitions were an effective way to reorient and then refocus its innovation core.

To this end, IBM addressed the critical intangible issues relatively successfully. It persuaded key people to stay engaged and keep the acquired firms' innovation churning. To achieve greater integration, IBM often let the acquired talents and cultures take charge, rather than the other way around. The more acquired innovation is dependent on intangibles, the more these sorts of "softer" things—not golden handcuffs—are key to make the integration of talent and technologies work. At least initially, some quibbled with the prices and purpose of IBM's acquisitions. They certainly did not transform the $80 billion behemoth into a fast-growth company overnight. But by most reasonable standards, IBM dramatically improved the payoff on these investments through both deft integration and by smartly leveraging these new technologies and talents to power forward its other core businesses.

Other firms in a wide variety of industries have pursued similar paths: GE Medical Systems, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, and even Microsoft. These approaches are grounded primarily in post-commercialization or combination deals (i.e., acquiring established high-tech products and businesses, even if a good chunk of R&D in process and innovative talent still is a key part of the mix). With greater emphasis on proven technologies and real businesses, these strategies are more akin to traditional M&A transactions. More conventional strategic tools and established metrics better apply and they might seem less risky. It's worth remembering, however, that the majority of even more "traditional" M&A stumble. Like any other approach, innovation by acquisition is a gamble. It's always a matter of doing as much as possible to better the odds. Over time, with sound strategies, reasonable prices, and effective integration, M&A can build a solid record of innovation success.

In contrast to more mature and evolutionary innovation-by-acquisition approaches, the upheaval of more radical and transformative R&D-oriented deals tends to cause greater problems. It is a daunting challenge to try to transform a company's innovation core suddenly and dramatically. Widespread internal strategic and organizational difficulties compound with technological and market uncertainty to make for unfavorable odds. Monsanto's attempt to switch rapidly from old-line chemicals to newfangled agricultural biotechnology stumbled in the late 1990s, for example. Its attempt at radical transformation through a series of rapid acquisitions turned out to be too far and too fast a leap into the unknown.

Limits of Innovation by Acquisition

The experience of King Pharmaceuticals also highlights the potential, and the limits, of innovation by acquisition. In its first decade, King made little investment in its own drug discovery and development. Instead, the firm was built almost exclusively by buying relatively minor, neglected products that no longer fit the portfolios of the ever-expanding big brand-name pharmaceutical companies. With massive drug industry consolidation and restructuring during the late 1990s, King snatched up products cast off from the likes of Bristol Myers, GlaxoSmithKline, and Johnson & Johnson. It paid relatively modest prices, sometimes as little as one or two times sales. King then reformulated the drugs, rejuvenated them, repackaged them, and remarketed them, often dramatically boosting sales and profits.

It wasn't the most high-tech, cutting-edge product development strategy, but it offered significant value-added innovation in its own relatively unique way. When King acquired the antihypertensive Altace from Aventis in 1998, for example, sales were just $92 million. By 2002, King boosted Altace sales to half a billion dollars. Using this bargain acquisition-and-repackaging strategy, King built a billion-dollar company in just a few short years.

Still, the novelty of King's strategy began to wear thin before long. Confronting a series of patent expirations and new generic competitors was bad enough. Perhaps worse was that, by now, others had noticed King's once-novel R&D by M&A strategy and had moved to replicate its success. With more competitive bidding and higher prices for secondary drugs being shed by Big Pharma, King was forced to reconsider its strategy. Without its own strong R&D or drug pipeline, it was unclear how much (or whether) King had any distinct and sustainable advantage with which to defend and grow its targeted markets profitably.

King had to decide whether to strategically shift its focus and invest a great deal more in its own internal R&D and other new sources of drug development, or to take the chance and rely on others to provide it with a continuing stream of product. Both options presented greater risks and costs going forward. Burdened with such a difficult choice and with its performance sagging because of its most recent pricier drug deals, King agreed to be acquired by Mylan Laboratories in mid 2004.

The bottom line is that it's extremely difficult to build a sustainable and lucrative innovation strategy solely, or even primarily, by acquisition. There's no guarantee that the key innovations a firm needs can or will be developed by someone else, that they'll be on the market when they're needed (if ever), and that they won't be either pre-emptively snatched up by another firm or else bid up by competitors to a price that captures or exceeds all the innovation's potential future value. These are some of the key, persistent problems with the use of acquisitions, however attractive the just-buy-it philosophy seems in the abstract. A firm's core innovation assets are the leverage with which acquisitions' value can be uniquely enhanced and multiplied, even in excess of rich purchase prices. In contrast, too much reliance on acquisitions, and a corresponding lack of core innovation, tends to put a firm in a weaker, more dependent, and less profitable position.

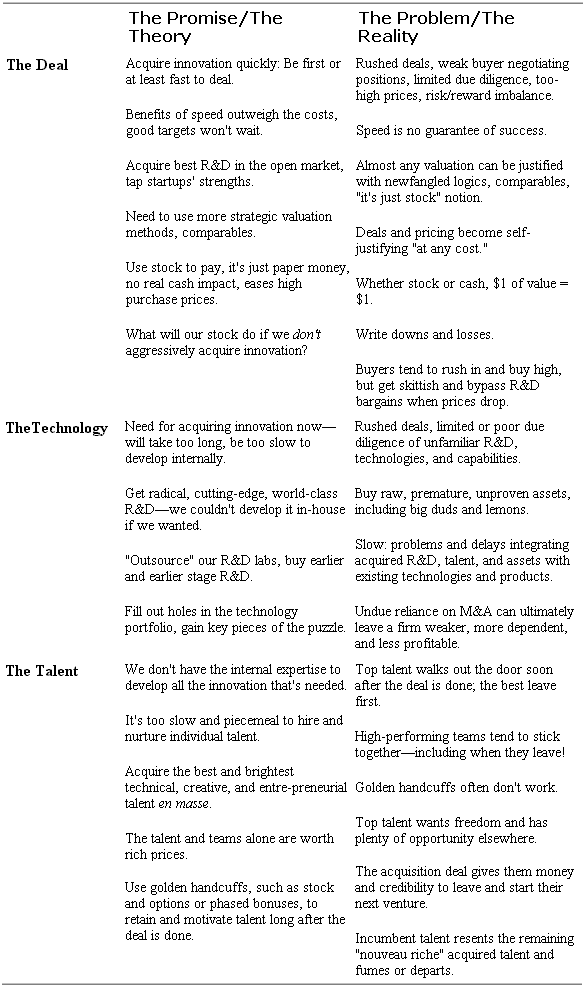

M&A have become an increasingly important innovation option, including even for more basic R&D tasks. Sometimes, M&A are an essential and irreplaceable tool. In the end, however, innovation by acquisition is an incomplete and imperfect approach (see Table 5-1). Even the most successful and diverse examples, from Cisco Systems to King Pharmaceuticals, show not only its potential, but also its costs, risks, and limitations. Rarely are M&A alone a sustainable and lucrative innovation strategy. It takes more than just the art of the deal.

Table 5-1. Innovation by Acquisition: Just Buy It?