Chapter 9. West Point and Woodstock: Authoritative Leadership and Democratic Decision Making

Rebel. Outlaw. Individualist.

Is there any company that embodies these images more than motorcycle manufacturer Harley-Davidson? Doubtful.

Since Marlon Brando challenged Harley-riding rivals in the film The Wild One, the company’s bikes have represented freedom, nonconformity, and excitement to millions of enthusiasts around the world. From the unmistakable rumble of its V-twin engine to the counter-culture sneer of its stock symbol (HOG), Harley-Davidson has stood as an American icon for more than 100 years.

Despite the fearsome roar of its bikes, however, Harley-Davidson’s management model once reflected a surprisingly New Age philosophy. “Beneath the image of a hard-riding, tough-as-nails Harley-Davidson bike is a company that thrives on the ‘soft’ side of management, emphasizing participation, inclusion, learning, and cooperation,” noted Fast Company magazine in 1997.1 Things didn’t start off with such an egalitarian approach.

Harley-Davidson wouldn’t be standing today had it not relied on a very strict, command-and-control management model to carry the company through some of its darkest days. In the early 1980s, the U.S. economy was slumping, and the motorcycle market was flooded with inexpensive Japanese imports. Harley-Davidson found itself drowning. In 1981, losses were mounting and market share was plummeting.

Knowing his company’s survival was at stake, then-CEO Vaughn Beals moved swiftly. He reduced the workforce by 40 percent and extracted wage concessions of 9 percent from the remaining salaried workers. In addition, he told all employees to forget about raises for at least two years.

Though draconian in nature, these directives helped stabilize Harley-Davidson until the company could introduce new products—such as the popular Softail line—and persuade the government to impose tariffs on Japanese manufacturers. By 1986, the company’s financial fortunes had improved.

Yet Harley-Davidson’s long-term outlook remained uncertain. Company insiders knew they couldn’t reduce costs much further or expect tariffs to compensate for shortcomings in manufacturing, distribution, and product design. Instead, Harley-Davidson needed ideas for making the company stronger. But where to find them wasn’t readily clear. Even existing leaders sensed they were running out of inspiration.

In 1987, newly appointed president and chief operating officer Rich Teerlink wondered if the command-and-control model that had carried Harley-Davidson through the crisis of the early 1980s was meeting the company’s long-term needs. “When an organization is under extreme pressure—so much so that one wrong move can mean its collapse—authoritarian leadership may very well be necessary,” wrote Teerlink after retiring from the company in 2000. “[But] I knew we needed big changes in the motorcycle division. We had to identify some sort of strategy that could carry everyone forward—everyone meaning employees, customers, and all other stakeholders. We had to improve operations. And I felt strongly that we needed to change the way employees were being treated. They could no longer be privates, taking orders and operating within strict limits. We needed to continue to push, and push hard, to create a much more inclusive and collegial work atmosphere.”2

Teerlink began to look for ways to drive decision making lower into the ranks of its employees. One of the things he did was to reach out to union workers and tell them they would play a role in helping to develop long-term company strategies. Then Teerlink pulled together teams of employees from different parts of the company, tasking them the big challenges of the day, including manufacturing defects and workforce morale.

Thanks to these and other changes, Harley-Davidson began to see improvements. By 1991, sales approached the $1 billion threshold for the first time. By the middle of the decade, orders outstripped supply—so much that Harley-Davidson had to expand its manufacturing capacity. With demand growing, the company’s stock mounted an unrelenting upward climb.

Armed with new ideas and fresh perspectives, Harley-Davidson’s leaders decided to eliminate altogether the hierarchical leadership pyramid and replace it with a more collaborative framework of overlapping “circles of leadership.” These circles took responsibility for product development, sales, and support and were complemented by councils tasked with leadership and strategy. From an outside perspective, it wasn’t exactly clear who did what at the company or who was in charge at any one moment. But insiders say the flexible framework provided an opportunity for more people to become involved in decision making. Soon, the circles were replicated throughout many parts of the company, and managers began singing the praises of the new model.3

The media and analyst communities were intrigued. A lovable management team produced bikes favored by Hells Angels? It was an irresistible attraction. A 1999 documentary for PBS Television profiled one Harley-Davidson plant in Kansas City where “natural work groups” oversaw production. The documentary described the facility as an “ideal workplace” where employees have “jobs of the future.”4

For several, magical years, the HOG was riding high.

Then the landscape for motorcycles changed. The baby boomers and Rolex Riders that flocked to the brand in the early 2000s were approaching their sixties. Planning for retirement, not reliving Easy Rider, was foremost on their minds. With the economy beginning to turn, the lure of a $20,000 discretionary purchase began to wane for many would-be bike owners.

Unfortunately, Harley-Davidson’s new-age management model was not optimized to handle the curves that lay ahead.

In 2007, for example, business got off to a rocky start after labor negotiations with workers at the York, Pennsylvania manufacturing facility broke down. Unable to reach an agreement after discussions, workers voted to strike. The company settled the strike within a few weeks, but the setback prompted it to lower financial expectations for the year.

Afterwards, Harley-Davidson couldn’t seem to get in gear no matter how hard it tried. As the company began a gradual evolution back toward command-and-control leadership in the late 2000s,5 it expressed optimism that sales would grow moderately. But in each year, they actually declined. Despite the best of intentions, Harley-Davidson was forced to trim its workforce—twice. By the end of 2009, a quarter of its workers were idle and management was looking for quick relief.6 Barely a year after acquiring MV Agusta, a high-end European maker of motorcycles, Harley-Davidson announced in October 2009 that it would reverse course and sell the company.7

How did things get so bad? As far back as a decade ago, there were signs that Harley-Davidson was beginning to operate with less speed. Former IT director Cory Mason summed up what many insiders had come to believe about the decentralized model: “In some respects, it’s slower because you have to bring all the stakeholders together.”8 The experience of Harley-Davidson begs the question of whether a company is better off with a command-and-control management model or with one that is more egalitarian. Harley-Davidson tried one, switched to the other, and is now switching back. Each, of course, comes with advantages and drawbacks.

Command-and-control models are typically patterned after military hierarchies studied at the top military academies around the world including Saint-Cyr in Coëtquidan, France, and the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, New York. Instead of generals, colonels, majors, captains, and lieutenants, however, businesses have senior vice presidents, vice presidents, directors, and so on. Power flows downward through a hierarchal pyramid of authority. Such centralized models provide scale, replicability, and accountability. Business leaders can be assured that their orders will be followed accurately and according to a clearly defined set of metrics. The downside to this type of model, however, is that it is not optimized for speed or flexibility. In top-down organizations, thought leadership is typically limited to a small few, and new ideas are often eschewed in favor of the status quo.

In contrast, collaborative environments that drive decision making deeper into an organization often foster creativity and operate with greater speed. In such decentralized environments, workers from all ranks are valued, not just for their labor, but their ideas, too. The beauty of such organizations is the ability to draw from a wide variety of inputs, without relying on a single person for approval on every decision. In many instances—from open source software to the famed Woodstock concert event of 1969—loose hierarchies, while unconventional, can produce extraordinary things. But these bottom-up models often suffer from an inability to execute decisively or measure progress accurately.

Scale or speed? Replicability or flexibility?

Over the years, companies have generally picked one model or the other. But in doing so, they cut themselves off from the benefits that the alternative provides. To combat this, some organizations, such as Harley-Davidson, change models as economic or market conditions warrant. But timing a management model to a specific set of environmental circumstances is risky at best.

What if you didn’t have to choose between top-down, centralized authority and decentralized decision making?

Maybe, the answer is to do both.

Cisco, the Early Years: Taking Orders, Following Directions

In its early years, Cisco did not always follow the principle of doing both. The company was originally governed by a traditional, centralized management model. For the most part, this served the company well, especially during the heady years of the 1990s.

With millions and then billions of dollars of revenue pouring into the company, and thousands of new employees joining it, Cisco needed to keep a tight reign over its operations. Among other things, the command-and-control model helped Cisco manage its growth and ensured company leaders could count on their initiatives to be executed quickly and efficiently. And they could measure how these decisions succeeded or failed.

In addition, this model disciplined leaders to view every decision through the lens of scalability. The question they often asked their lieutenants was, “Will it scale?” If the answer was “No,” then employees were pressed to focus their energies on things that would.

While this enabled Cisco to keep up with demand for its core products, it made the company more rigid and less accepting of alternative ideas.

That included input from some of its own veterans. “For a super-capitalist company, it ran more like a centralized, planned economy,” says Bob Agee, a former vice president who joined Cisco in 1997 to run operations in Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States. “When I was 22-years-old working on my own as a young country GM in Nigeria for Xerox, I had more autonomy than I did as a Cisco vice president.”

The company’s reluctance to look at things differently also made it difficult for Cisco to foresee new opportunities or potential calamities. Never was that more apparent than when the bottom on the market for telecommunications equipment and services collapsed in 2001.

Within a few short months, Cisco’s sales fell by half, and the company was stuck with $2 billion worth of inventory it could not sell. In a painful decision, the company was ultimately forced to cut 12 percent of its regular employees.

Afterward, CEO John Chambers began to wonder if the company’s reliance on a single management model was a major part of the problem. Command-and-control served the company well in so many ways. But it didn’t enable the company to pursue more than three or four corporate priorities each year. And it didn’t allow Chambers to leverage the on-the-ground knowledge of his business leaders to the fullest extent possible.

Would it help to drive decision making deeper into the company and open it up to a large number of managers? More and more Chambers began to believe so. He knew he had plenty of people who could make decisions, and he was confident that having more minds focused on more opportunities would bring about better resolutions to business challenges.

The more Chambers thought about the idea, the more he became convinced that the ideal corporate structure wasn’t a choice between command-and-control or decentralized decision making, but a judicious blend of both.

By blending the best of both models, Chambers reasoned, Cisco could better anticipate opportunities and prepare for challenges, rather than merely reacting to them.

Power to the People: Inside Cisco’s Councils and Boards

To get more company leaders more involved in decision making, Chambers started shifting certain powers from the company’s traditional business owners—think heads of sales, marketing, manufacturing, and engineering—to newly-formed teams populated with managers from various parts of the company. Known as councils and boards, these teams complement the company’s more traditional hierarchy, providing the scale and replicability of a centralized company and the speed and flexibility of a decentralized one.

Unlike informal company committees, Cisco’s councils and boards have very specific missions and duties.

Councils form around opportunities that have the potential to drive $10 billion in annual revenue within 3 to 5 years. Today, the company has nine councils: five focused on customer segments, two on innovation, and two on operational excellence. Councils set the long-term direction for their respective segment or area, championing investments and go-to-market priorities. Each council is responsible for its business segment or specific cross-segment goal.

For instance, you may remember the Emerging Countries Council, which was discussed in Chapter 6, “The Beaten Path and The Road Less Traveled.” That council helped double Cisco’s business in emerging countries between 2006 and 2008.

What makes the councils unique is that they are populated with—and led by—cross-functional teams of senior executives who are empowered to make critical business decisions “at the table.” Each council is composed of executives representing a range of functions, such as sales, finance, operations, IT, and marketing. Each member has the authority to approve or disapprove plans without having to check with a boss. Because of this, decisions about entering new markets, making acquisitions, and reallocating resources now move quickly and effectively.

Not surprisingly, council leadership is among the most sought-after assignments in the company. To ensure that each council has the right cross-functional composition, Chambers is personally involved in selecting leaders and members.

In addition to the councils, there are more than two dozen active boards that report to the councils and align to Cisco’s ever-expanding list of priorities. Boards form around market opportunities that can drive $1 billion in annual revenue within 3 to 5 years.

For example, Cisco scaled Stuart Hamilton’s sports and entertainment initiative with a newly created board. Leveraging Hamilton’s early successes, the board garnered more resources than Hamilton alone could secure, providing a foundation that allowed Cisco to capture new opportunities. The board is now engaged with more than two dozen major stadium and team owners and is building a potential billion-dollar business.

Cisco has also formed boards around China, sustainability, advertising, and smart power grids. After major goals have been reached, boards are disbanded, and their duties transferred to traditional functions inside the company.

And members are not just senior executives. The boards and councils also commission small working groups of employees to come together, solve a particular problem, and quickly disband.

The beauty of the boards and councils is that they do not operate independent of Cisco’s traditional hierarchy. Instead, the two work together. This dual structure is designed to provide Cisco the efficiency of a top-down company with the customer intimacy and responsiveness of a decentralized one (see Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1. Authoritative leadership and democratic decision making

“At Cisco, the traditional organizational structure is no longer the primary lever for getting work done,” says Brian Schipper, senior vice president of human resources. “We maintain traditional leadership roles, but we complement them with teams of people who can make decisions horizontally across the organization, resulting in a significant acceleration of work.”

Of course, not everyone is convinced.

Since Cisco introduced its councils and boards, scores of analysts, journalists, and other company watchers have questioned the wisdom of the model. “Management by committee,” some say. “Corporate socialism,” others have mused. Some have even wondered if Cisco is practicing “matrix management in disguise.”

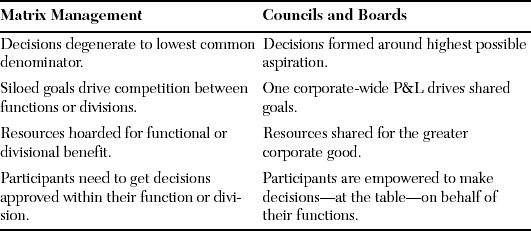

None of these is accurate. Take matrix management, for example. While matrix models have certain benefits, they have been inadequate when it comes to improving cross-functional effectiveness. In a matrix organization, employees tend to defend their functional resources and focus on functional duties. Conversely, Cisco councils emphasize collaboration and teamwork. They start with a shared goal and then devise a workable strategy with which to achieve it (see Table 9.1).

Table 9.1. Councils and Boards Versus Matrix Management

The critiques come as no surprise to Cisco, which has been adapting the model since it was first unveiled in 2002. In fact, the company did not see strong results from the first generation of councils partially because executives were not particularly enthusiastic about participating. They had more allegiance to their parent organizations than to the councils and were not empowered to do anything but make recommendations for solving cross-functional problems.

While the councils originally served as mere obstacle removers, they soon began to set the strategy and drive initiatives for their respective areas. Today, councils are accountable for revenue growth, profit contribution, customer satisfaction, and market share in their customer segments, while the traditional business functions maintain responsibility for their own functional areas.

But councils do more than deliver numbers for the company. They also serve as a way to develop future leaders.

“What we try to do is get individuals working on councils and boards to move out of their areas of expertise and rely less on functional knowledge and more on leadership skills,” says Randy Pond, executive vice president of operations, processes, and systems. “When they have shared goals before them, we are best able to leverage their individual experiences, ideas and disciplines.”9

Take Executive Vice President Sue Bostrom, for example. She not only leads Cisco’s marketing organization, but also co-leads the Small Business Council. Similarly, Chief Technology Officer Padmasree Warrior co-leads the Connected Architecture Council, while Chief Information Officer Rebecca Jacoby serves on the Enterprise Business Council.

So how does a company empower employees and ensure that they follow management’s expectations? That is a tricky challenge for any company, let alone one that is trying to extend decision-making authority to as many as 3,000 leaders. Implementing the dual management model was necessary, but it was not sufficient. Recognizing the enormity of the challenge, Cisco devised an additional mechanism to get its people aligned, moving in the same direction and speaking the same language.

Here’s how.

One Cisco, One Page: How Discipline Improved Alignment

At various times throughout its history, Cisco has navigated around certain plateaus that have stymied other companies. Think sales thresholds, market expansions, and acquisitions. In doing so, Cisco has had to refine strategy and execution plans on an ongoing basis. But the challenge associated with this effort has frustrated company leaders on occasion. Why was it sometimes so difficult to align strategy and execution and at other times, so painless?

Leaders eventually discovered that different parts of the company used different terminology, tools, and mechanisms for discussing opportunities and measuring outcomes. When consistency and discipline were missing, confusion and misunderstanding often filled the void. In other words, Cisco had a basic process and language problem.

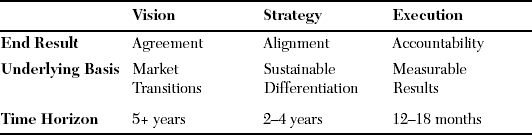

“If we get our people speaking the same language and using the same measures of accountability, would our strategy and execution both improve? Would our collaboration increase?” many wondered. The questions led to the creation of a new discussion framework that Cisco began to use internally. It revolved around three simple words: vision, strategy, and execution.

To eliminate any ambiguity, Cisco attached a very precise meaning to each word so it would trigger behaviors universally understood throughout the company. Specifically, Cisco defined “vision,” “strategy,” and “execution” as follows:

• Vision—A 3- to 5-year value proposition Cisco will deliver to customers, based on market transitions. It answers a simple question: What is the end result we want to accomplish? Its time horizon is typically 5 years or more.

• Strategy—The key attributes and actions that sustain Cisco’s differentiation over multiple generations of products and services. Its time horizon is typically over the next 2 to 4 years.

• Execution—A series of activities that Cisco will undertake and measure over the next 12 to 18 months to carry out the objectives behind a strategy.

In essence, V, S, and E can be simplified to: Where Are We Headed; How Will We Get There; and What Are We Doing? In practical terms, the Operating Committee sets the company vision, the councils define the strategy, and the functions execute.

“The vision drives agreement, the strategy fosters alignment, and the execution promotes accountability. It’s not just taxonomy. It’s actually a tool for getting employees to lay out a plan in terms that everyone can understand and to which they can execute,” according to Cisco Vice President Ron Ricci, a key champion of the approach (see Table 9.2).

Table 9.2. VSE Drives Agreement, Alignment, and Accountability

Since unveiling the VSE framework, Cisco has found that it can move with greater consistency, which has helped Cisco operate with agility to take advantage of market transitions that come about by changing business conditions or technological breakthroughs. Take the consumer market, which Cisco has entered with high expectations.

In 2010, for example, consumers in the United States alone are expected to spend upwards of $165 billion on consumer electronics—everything from mobile phones to flat screen televisions to digital recorders to home networking products and more.10 That’s 63 percent more than they spent in 2004.11

Until recently, Cisco had captured only a fraction of the annual spending. One reason: the company’s ad hoc approach to the market. Prior to developing the consumer VSE, various business units were trying to serve different parts of the market independent of one another. Cisco’s service provider group, for example, developed cable set-top boxes for home users, while Cisco’s Linksys group sold point products to consumers through retailers without leveraging the broader Cisco sales machine. Then there was the company’s media solutions group, which was building platforms for social networking, content targeting, and site administration all by itself. Instead of cross-functional decision making and execution, different groups operated in isolated silos. This was exemplified by Cisco’s initial consumer marketing approach, which was little more than a house of brands that bore little resemblance to the “Cisco” name.

Without an integrated vision or strategy, many inside and outside of the company struggled to understand why Cisco was in the consumer business at all. The low-margin, high-volume consumer business model seemed at odds with Cisco’s core business model, which revolved around catering to big-ticket business customers who paid top dollar for equipment in return for world-class engineering and unrivaled support. In contrast, the consumer market prized rapid innovation above all else—except, perhaps, for competitive prices.

To provide clarity to outsiders and insiders alike, Cisco’s Consumer Business Council rigorously applied the VSE framework to everything that it was doing in the consumer market. That included everything from the products it developed to the partners it engaged to the branding policies that it pursued.

To develop its vision, the company zeroed in on three macro trends: the rise of the empowered user, the increased connectivity of consumer devices, and the growing use of video. More than simple evolutions, these market transitions represented some of the biggest changes yet in telecommunications, consumer electronics, and computing. Take the rise of the empowered end user, for example.

“When I started at Cisco, we would innovate at the enterprise level and then drive out our investments into R&D for the mass market,” says Ken Wirt, vice president of consumer marketing. “Now the investment paradigm has been flipped on its head. Today, innovation starts at the consumer level, and makes its way back into the enterprise.” One example of this is the way the new generation of workers ushered into the workplace collaborative technologies like Facebook, Twitter, and instant messaging. Rather than wait for IT managers to deploy these tools in a traditional top-down, enterprise-wide fashion, younger workers simply started using them in their jobs. This trend represents a fundamental shift in the way that enterprises acquire and use technology, and in the way that workers collaborate.

More than just in the workplace, empowered users are exercising influence in far greater ways, including how products are designed, manufactured, and brought to market. More and more, they are demanding ubiquitous connectivity in consumer devices so they can communicate anytime, anywhere, and on any device. This has led to the introduction of a variety of connected devices—everything from personal computers to digital video recorders to MP3 players. That’s quite a change from just a few years ago when only your mobile phone and your computer connected to a network. Today, almost everything in your briefcase and your child’s backpack connects. If it has a chip or a plug, chances are it is online.

And what are people doing with their networks? Putting more video on it. Take YouTube: Every minute, 20 hours of video is uploaded to the popular video hosting and viewing site. Every day, hundreds of thousands of new videos are uploaded, according to the company.12 With these trends in mind, Cisco articulated its consumer vision: “Enabling people to live a connected life that is more personal, more social, and more visual.”

This vision, you might notice, directly addresses each of the three major market transitions. Personal refers to the empowered user. Social focuses on connectivity. And visual, of course, rallies the team around video.

Just as the three transitions formed Cisco’s vision, the link between them soon formed the crux of Cisco’s strategy: “Leverage the network as the platform to deliver the next generation of consumer video experiences—integrating devices, software, and the Internet.” The latter—the architectural integration of the devices and the leveraging of network—was key to the company because it formed the foundation for its sustainable differentiation going forward.

Cisco’s push into consumer markets has yielded substantial gains. Consumer sales are robust, relevance with media companies is increasing, and Cisco’s influence in video continues to rise. There are more than 200 million Cisco devices in homes today.

To long-time company veterans including Senior Vice President Ned Hooper, who leads the consumer business for Cisco, the impact of the consumer VSE cannot be overstated. “The vision made us agree on a common destination, and the strategy gave us focus. The execution, meantime, helps us prioritize. Thanks to this, we’ve combined devices and software over the Internet to create new experiences,” he says. “You can only do that if the whole company comes together.”

What a Difference a Decade Makes

When the technology bubble burst in 2001, Cisco was ill-prepared for what followed. Given the company’s centralized management model, all it could do was react to external forces.

Contrast that with the economic freefall of 2008 and 2009. Thanks to the dual management model, Cisco was better able to navigate its way through an economic downturn than ever before.

When Cisco realized that orders were slowing and an economic downturn was imminent, the company’s command-and-control leadership model kicked into high gear. Within weeks, executives identified $1.4 billion worth of discretionary spending that they could target for elimination. Because of the authority they wielded, they were certain that their directives to eliminate travel, cut back on the use of outside contractors, and even to raise cafeteria prices would be followed. And they were—immediately.

That was the easy part.

The hard part was identifying which projects to eliminate and which to prioritize. That’s where the councils stepped in. Thanks to their more hands-on knowledge of intimate details deep within the company, councils and boards identified an additional $500 million that could be put to better use. And they did so within just three months.

Take the Enterprise Business Council (EBC), which focuses on opportunities with large, corporate customers. After reevaluating priorities in light of the slowdown, the EBC decided to concentrate investment resources on several of Cisco’s most strategic customers. By better meeting their business and technology needs, the council helped drive a 15 percent jump in product sales and a whopping 131 percent spike in services sales within these accounts.

Thanks to doing both—a centralized model that maintained a tight reign on expenses and a collaborative model that zeroed in on new opportunities while reprioritizing initiatives—Cisco avoided the wholesale layoffs that plagued many technology companies in 2008 and 2009.

While others were hitting the brakes, Cisco was revving the accelerator. During a single quarter in 2009 alone, it made four acquisitions.

“When you do four acquisitions in a quarter—two of them multibillion dollar—you really do have to have your teams moving in a couple of directions. And you have to coordinate them. That’s a perfect example of how [Cisco has] been utilizing cross-functional teams,” said Catharine Trebnick, a senior analyst at Avian Securities.13

Another benefit of the dual management model? The company still scales. By increasing the number of decision makers inside the company, Cisco has been able to expand its list of annual priorities from a mere handful per year to several dozen at once. In 2010, for example, the company boldly set out to purse two dozen new markets.

And the result of all these benefits: With its blend of authoritative leadership and democratic decision making, Cisco can run like a finely-tuned Harley rumbling down the highway.