Chapter 2: Discovering a Disruptive Opportunity: Explore the Least Obvious

Being insightful isn’t a question of talent; it’s a question of awareness.

“The most important advances are the least predictable ones.”

—Sir Francis Bacon1

People often say, “Apple doesn’t do consumer research.” This usually precedes an argument against the need for market research of any kind. But, the designers at Apple do conduct research—it’s just not the traditional kind you read about in consumer behavior textbooks. It’s informal, impromptu, and driven by acute observations of the context in which their products are used. Being insightful isn’t a question of talent; it’s a question of awareness.

Awareness is essentially being mindful of the cultural and social constructs that surround you and the people for whom you are creating something new. You’ve felt it before. The moment you decide you’re going to buy a yellow MINI Cooper, you start seeing them all over town. Of course, they were there before, but the difference is that now your awareness has been focused.

All the Apple designers I’ve met share this awareness of context, which may explain why they’re often sensitive to critical details that their competitors overlook. They examine the context for themselves rather than having it described by someone else. Jonathan Ive describes his observations of people interacting with Mac computers in an Apple store: “When people are looking at Macs in stores, they’re drawn to them in a very physical way. They don’t mind moving them around or touching them.”

That observation lead him to an important insight: “You’re seldom intimidated by something that you can feel. If you’re intimidated by an object, you tend not to want to touch it.”2

So, for Apple, there was an opportunity to give people a tangible sense of control over the technology by establishing an immediate physical connection between the user and the computer.

Think again about the statement “people are seldom intimidated by something they want to touch.” That’s an insight that wouldn’t have been possible without close, unobtrusive observation of people interacting with technology. To cultivate insights and uncover opportunities, you need to observe the telling moments that reveal what consumers actually feel and do (as opposed to what they say they feel).

In Chapter 1, you identified a number of clichés, got rid of some of them, inverted and exaggerated the scale of others—and you came up with three disruptive hypotheses. But, hypotheses don’t exist in a vacuum. The people you expect to experience the shift you’re describing must believe that the change delivers value. So, when you consider how to put your hypotheses into action, you must stay focused on who’s involved in the situation and their needs.

Why is this important? Because disruption for disruption’s sake is just annoying. The reason most hypotheses fail to make it past the “what if” stage isn’t that they’re too radical; it’s that the advantages of the disruption aren’t clear. Or, put a little differently, it’s not their lack of creative differentiation; it’s their lack of customer insight.

Being truly insightful—and I’ll show you exactly how to do that—involves immersing yourself into the world of your customers to try to see how things look from their viewpoint. The focus is on watching, not on talking. We’ll start by looking at the real-world context your hypotheses will exist in. Who lives there now? What do they need? What motivates them? It’s all about taking those hypotheses and translating them into actionable opportunities.

Be Quick and Informal

Officially, the methods of understanding the context I’m describing in this chapter fall under the general heading of ethnographic or contextual research.3 The name isn’t important. This research, whatever you want to call it, is designed to be quick and informal, intuitive and qualitative, and above all, accessible. It shouldn’t take you more than two or three days and, in many cases, it can be done in as little as two or three hours.

Of course, you could go out and spend several months and tens of thousands of dollars on detailed demographic and psychographic market segmentation, focus groups, and quantitative studies. But, I think you’ll get much better information—particularly while you’re at the beginning of creating something new—by simply watching what people do and asking a few well-planned questions. That’s something you can usually do for free or close to it. The point I’m emphasizing is that anyone can (and should) feel empowered to go out and create new business ventures, products, and services, without drowning in the sea of complexity that makes up typical market research projects.

Just to clarify: I’m not claiming that this process is comprehensive. It’s not supposed to be. It is, however, an effective way to start developing qualitative observations. You’ll be able to go through the process quickly, and you’ll know early on whether it’s working. If it is, you move on to the next step. If not, you can go back, tweak it, and do it again without losing much time or money.

After you gather that information and determine your context, you’ll organize, filter, and prioritize your observations and transform them into meaningful insights.

What Are Your Observations?

Before you dive too far into your research, you need to have a clear idea of the core questions that you want answered. These aren’t questions that you’re necessarily going to directly ask customers. (You may ask some of them, but you’ll get a lot of the information you’re looking for through observation.) Your research goals will be influenced by the provocative hypotheses you created in Chapter 1, and you’ll want to focus on the relationship between the customer and the industry, segment, or category:

• How and where do customers interact with the current products and services in your industry, segment, or category?

• What steps do they have to take to purchase products and services?

• How does the industry, segment, or category make the customer feel?

• What is the social network of the customer?

• Is the customer loyal to an existing product, service, or brand?

• What is the level of customer support offered?

Of course, before you can start observing anyone, let alone asking questions, you must have a general idea of whom to watch and speak. You definitely want to connect with a group that business consultant Robert Gordman calls must-have customers—the customers who share similar characteristics and are currently the most profitable ones in the situation you’re focused on. Target people based on demographics (such as gender, age, marital status, education, and so on) and some situation-specific characteristics (such as foodie, early adopter, technophobe, and so on). But, don’t let yourself get too boxed in by those standard segmentations. At the same time, don’t forget the outliers—the people no one in your industry is looking at. These folks could turn out to be the most important group of all.

For example, I was recently involved with a project to design a new TV remote control. Our research team at frog design did tons of in-home visits. We spent hours watching people in action, learning about what they liked and what they hated about their current remotes. We also sent a team out to meet with blind people to observe how they used remotes and talk to them about the features they preferred and how they liked the buttons to be clustered. Traditional market research would never have bothered with blind consumers. But, the insights we generated from those visits were invaluable. After all, how many times have you been watching TV in the dark and changed the channel instead of turning up the volume because you couldn’t see the buttons?

After you’ve got a handle on your research goals, your next task is to figure out how to do the actual observing. I’ve summarized my three favorite methods:

• Pre-arranged, open-ended interview and observation. This is the most common type of study. As the name implies, while you’re asking questions designed to get your interview subjects to speak freely, you’re also carefully observing the environment they live or work in and what they’re doing while they’re there. This is exactly what Intuit’s “Follow Me Home” program was designed to do when the company was creating Quicken, its money-management software product. Engineers spent hours in real customers’ homes watching their behavior and identifying their real needs. Then, they went back to their cubicles and incorporated what they’d learned into the next version of the program.

“When the Quicken team came to my house, I thought they just wanted to find out how they could better advertise to me and people like me, but it wasn’t that at all,” said Wendy Padmos, one of dozens of volunteer participants in the program. “It was much more customer-focused. They wanted to know how I used their product, what was important to me, and what was not important to me. I told them I would like the ability to see my current spending against my average spending over the last 12 months, and now it’s in the product!”4

• Noninvasive observation. Because of constraints such as time or access, you may have to make your observations in public environments without prior permission. This can reveal a lot of information, especially in high-density areas. Because you’re operating in common public space, there’s no need to schedule your observations (and you shouldn’t anyway).

There’s a great story about the architect Louis Kahn and how he designed the green spaces between the buildings of the Salk Institute. Supposedly, Kahn, in his original plan, didn’t include any marked or paved pathways through the grassy areas. Instead, he observed pedestrian traffic and eventually created paths that corresponded exactly with the routes people were really taking. How many times have you seen beaten trails that veer off from marked or paved paths?

• Intercept. This approach includes visiting a store, watching the purchase process or general customer interactions, and approaching people to speak with. Your aim is to understand how people make purchase decisions (or decisions not to purchase) right while it’s happening.

The observation method(s) you opt for will depend on a number of factors, including your budget, time schedule, and the people you’re planning to observe. For example, if your target group includes elderly diabetics, you’ll probably want to spend at least some time doing in-home visits. Home visits might work for a teen population, too, but you’ll also want to hang out at shopping malls and at midnight screenings of the latest vampire movie.

What, Exactly, Am I Looking For?

The most common question I hear when people are new to contextual research is, “What am I looking for?” The most common answer is “pain points.” Unfortunately, in most cases, that’s the wrong answer. Business people are trained to focus only on problems—things that don’t work and need fixing. They live by the motto, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

The most highly rewarded managers are often those who can quickly identify critical problems, analyze complex sets of data, and apply razor-sharp reasoning to come up with a solution. Most managers have become experts at this process, and they’re motivated (often by hefty performance bonuses) to reach an endpoint or conclusion as soon as possible. Ultimately, I think that most researchers are trying to identify problems to solve.

However, actually coming right out and saying so usually causes immediate paralysis. The researcher becomes so preoccupied with spotting the big “broken” problems that he or she completely ignores everything else. Problems are also seductive because they’re usually clear. The customers’ frustration is visible and, even as an outsider, it’s easy to empathize. But, more often than not, it’s the small, seemingly unbroken aspects of a situation that provide the richest opportunity areas for innovation. These are often the nagging issues that linger for a long time without receiving much attention. They tend to be the things we ignore, precisely because they don’t change.

Consider the humble can of house paint. For years, cans of paint have been made of tin and opened the same way: pried open with a screwdriver. But then, Dutch Boy Paint came along and introduced the Twist & Pour, an all-plastic gallon container featuring an easy twist-off lid and a neat-pour spout, which reduces the spilling and dripping typically associated with traditional paint cans. A molded handle allows for a more controlled pour and easier carrying. Adam Chafe, Dutch Boy’s director of Marketing says, “Consumers told us the Twist & Pour paint container was a packaging innovation long overdue.”5 As this example shows, a satisfactory way of doing something (like opening a can of paint with a screwdriver) may be far from optimal.

So, instead of large pain points, you should spend your time looking for—and addressing—something much more subtle: small “tension points,” the things that aren’t big enough to be considered problems. The challenge, however, is that tension points are usually hard to spot, because the symptoms are easy to overlook. They’re not screaming for attention the way “real” problems are. They’re typically little inconveniences that people have grown complacent about.

The Twist & Pour paint container by Dutch Boy was a packaging innovation long overdue.

Tension points are a lot easier to identify after you have an idea of what to look for. Here are four specific types:

• Workarounds: These quick, efficient-seeming solutions address only the most obvious symptoms of a problem, not the underlying problem itself. Workarounds can actually be dangerous because, when symptoms clear up, people lose any incentive they may have had to deal with the real issues. Over the long term, the problem gets worse and, eventually, someone will have to come up with another workaround. In systems thinking, this vicious cycle is referred to as “shifting the burden.”

Author Seth Godin has his own term for workarounds, which he describes in a blog post: “Global warming a problem? Just shave the bears. Let’s define ‘bear shaving’ as the efforts we make to deal with the symptoms of a problem instead of addressing the cause of the problem. A rare Japanese PSA (public service announcement) showed a girl shaving a bear so it could deal with global warming.”6

In a frog design project for one of the big three automakers, we learned that, in the words of project lead, Mike LaVigne, “There’s much more happening than just going for a drive.” Mike and his team discovered that a lot of people check email, make phone calls, and use their laptop while they’re in their cars, even though the in-car experience wasn’t designed to support those activities.

Keep your eye out for quick and ready fixes that people have created to “work around” less than ideal situations (Post-It notes on a computer screen, for example).

• Values: People’s values play an important role in their motivations. What do they value? What’s important to them? What’s not? Men and women, for example, shop in different ways. Numerous studies have shown that women are especially interested in establishing a rapport and relationship with a knowledgeable salesperson. Men are more motivated by the proximity of parking to the front door of a place they’re considering shopping in. Tension is often present when a product, service, or experience is in conflict with the values they find desirable. This can reveal important shifts in the qualities consumers find meaningful.

In his article for Wired magazine, “The Good-Enough Revolution,” Robert Capps outlines a change in consumer values that he calls the MP3 effect:

What has happened with the MP3 format and other Good-Enough technologies is that the qualities we value have simply changed. And that change is so profound that the old measures have almost lost their meaning…. We now favor flexibility over high fidelity, convenience over features, quick and dirty over slow and polished. Having it here and now is more important than having it perfect. These changes run so deep and wide, they’re actually altering what we mean when we describe a product as “high-quality.”7

Capps lists Netbook computers, e-book readers, Skype video conferencing, a Kaiser Permanente “microclinic,” and even the MQ-1 Predator plane as examples of the MP3 effect.

Look for high-priority and low-priority values. Has there been a change in what consumers’ value in the products and services they buy? Has that change revealed a gap between what consumers want and what’s actually available?

• Inertia: Generally, the more established people’s habits, the higher the inertia, meaning they’re less motivated to consider alternative choices. Many banking customers, for example, say that they dislike their bank and would be delighted to switch. But, the prospect of closing all of their accounts and reopening them somewhere else is so overwhelming that it’s easier to just stay where they are. The same kind of thing happens in many other sectors, such as telephone or television services. Wherever customers feel trapped by inertia in a situation they find less than desirable is where you’ll find tension. Keep an eye out for situations in which customers act out of habit. Opportunities can be created to either break or leverage that inertia.

In October 2005, Bank of America identified an opportunity to encourage consumers to open new accounts. The bank discovered a key point of inertia—people often round the amount of their financial transactions up to the next dollar because it’s faster and more convenient. Could that inertia be leveraged to turn a habit of losing money into a habit of saving money? The result is a program called Keep the Change, in which, each time you make a purchase with a Bank of America Visa debit card, the bank rounds up the amount to the nearest dollar and transfers the difference into your savings account. Since its launch, over 700,000 have opened new checking accounts, and 1 million have set up new savings accounts.8

• Shoulds versus wants: People often struggle with the tension between wants, which are things they crave in the moment, and shoulds, which are the things they know are good for them in the long term. In their column for Fast Company magazine, Dan and Chip Heath make the case that “People need help saving themselves from themselves, and that presents a business opportunity.”9 They reference the work of Katherine Milkman, a doctoral student at Harvard Business School. Milkman has studied the way customers wrestle with wants and shoulds, and she suggests bundling the two. For example, the Heath’s write, “exercising is a should, so what if your gym offered to receive your magazine subscriptions? That way, if you wanted to read the new Vanity Fair (a want), you’d have to drop by the gym. Or, what if Blockbuster offered you a free tub of popcorn (a want) for every documentary (a should) that you rented?”10

Look for the tension that lies between wants and shoulds. Treat all customers as highly invested in moving from where they are to where they want to be. Do they need help “saving themselves from themselves” to get there?

A Few Final Tips

Ideally, you should do your research in teams of two or three, instead of by yourself. Have one person do the interviews and one (or more) observe and record participants’ behavior.

Remember that the customer is the expert and plays the lead role in the conversation, while you listen and probe with follow-up questions. That kind of dialog enables you to clarify details and avoid misunderstandings about what people do and why.

Stay focused on observing. Sure, you’ll ask some questions, but unfortunately, that’s not always the best way to gather information. In fact, it can often be misleading. People comment only on what they know and have experienced. They may well point out problems and defects, but they’re much less able to suggest new insights. Their obvious needs are not the only ones and the non-obvious needs are often the richest source of new insights.

Make sure you document everything you’re doing in at least two ways. This includes notes (handwritten or typed), photographs, video, audio, participant output in the form of drawing, writing, survey, digital entry, and so on. At the least, use notes and photographs.

Finally, don’t edit yourself. You can always cut later.

Observations aren’t any good when they’re stuck in your head or stored on your laptop.

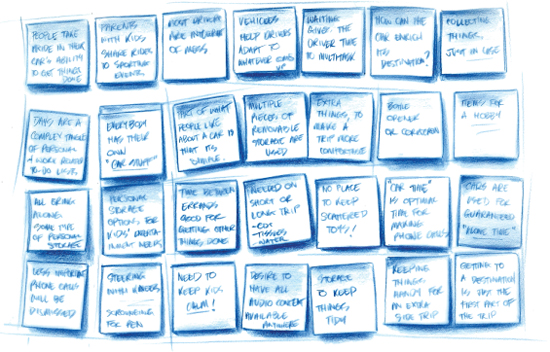

What Did You Find Out?

After you complete your field research and have your observations, the next step is to make sense of your discoveries. Observations aren’t any good when they’re stuck in your head or stored on your laptop. You need to make them tangible and get them out and onto a physical space. There’s a variety of ways to do this, but they all involve putting your observations on paper. You can use regular paper, card stock, Post-It notes, or anything else that works for you. Aim for one observation per Post-It note or card. And don’t forget to print out any photos you took. At frog design, we call this process “grounding the data.”

The next step is to take all those pieces of paper, photos, and any other memory aids (notes you took on the back of a napkin, brochures, business cards, and so on) and transfer them to what we call an “insight board.” At frog design, we use a large foam-core board, around 10–12 feet tall, 4–5 feet wide, which we lean against a wall. (You probably won’t need anything that big—a white board, bulletin board, a large sheet of butcher paper, or even a kitchen table is just fine.) Insight boards allow you to see all of your research findings together.

I realize that what I’m describing here sounds (and actually is) hopelessly low-tech. Some digital tools enable you to do roughly the same thing, but our goal here is to get you to close your laptop. There’s something about writing your ideas on paper and physically moving them around that makes the entire process feel more real to everyone involved. It also makes it easier to organize your thoughts, and it can help you stay out of some easy-to-fall-into thinking traps.

Set up an “Insight Board.”

In their book The Myth of the Paperless Office, Social Scientists Abigail Sellen and Richard Harper agree that when it comes to performing certain kinds of creative tasks, paper has many advantages over computers:

Because paper is a physical embodiment of information, actions performed in relation to paper are, to a large extent, made visible to one’s colleagues…. Contrast this with watching someone across a desk looking at a document on a laptop. What are they looking at? Where in the document are they? Are they really reading their e-mail? Knowing these things is important because they help a group coordinate its discussions and reach a shared understanding of what is being discussed.11

With your observations in a tangible form, it’s time to organize them into themes. So, where do you start?

When people get back from doing their contextual research, they normally have a few key takeaways bouncing around their heads, the big observations that they feel they’ve made, or the things that really excite them. These are the observations they talk about most, the first words out of their mouth when someone asks, “Hey, what did you find out?” Unfortunately, people’s excitement about these key observations can blind them to everything else. They may consider other observations, but they’ll eventually loop back around to the key ones. After those key observations have taken hold (which happens on a mostly subconscious level), it’s almost impossible to shift your perspective, and your ability to recognize patterns is crippled.

Because those key observations are going to be on your mind, you might as well start working with them first. So, start searching through your other notes for observations that potentially have a connection to the key ones, and cluster them together. As you’re going through this process, you’ll undoubtedly find other observations that are connected in some way. Make clusters for those groups as well. After a while, you’ll probably find that you can start grouping clusters together into larger themes. On the car project, for example, we identified the broad theme of “being prepared,” which was made up of the following observations of how drivers used their vehicles:

• Collect things “just in case” (gloves, jumper cables, first-aid kit, camera)

• Keep things handy for an extra side trip (items for a hobby, bottle opener, blanket)

• Carry extra things to make a trip more comfortable (CDs, tissues, lip balm, water)

Organize your observations into themes.

Coding Your Observations

It’s always a good idea to use different colors, paper sizes, or markings of some kind to code your key observations, supporting observations, and themes. I use different sized and shaped Post-It notes, but you can use anything you want, as long as it’s consistent and everyone understands what means what. For example, you might start out with all of your observations on yellow notes. After you identify the key observations, write those on blue notes. After you cluster and organize, mark your themes with a green note.

The point of organizing observations into themes is to lay the foundation for generating insights.

What Are Your Insights?

There’s a wonderful New Yorker article titled “The Eureka Hunt.”12 It’s the story of a firefighter named Wag Dodge who survived an out-of-control fire in the Mann Gulch, Montana, in 1949. Thirteen other smoke jumpers died in the fire. But, Dodge was saved by a brilliant insight. Fleeing for his life, he suddenly stopped running and ignited the ground in front of him. He then lay down on the smoldering embers and inhaled the thin layer of oxygen clinging to the ground. The fire passed over him and, after several terrifying minutes, Dodge emerged from the ashes, virtually unscathed. What sort of a crazy person stops running from a fire and starts another one? Well, if you know certain things about fire and oxygen, knowledge that may have taken years to acquire, it’s not as nutty as it sounds.

The Mann Gulch fire example is, admittedly, a bit extreme. And it probably has you wondering whether it’s possible to learn how to produce insights or if you have to wait until a bolt of lightning hits you. To the latter, the answer is a definite No.

While some insights do spontaneously appear, most are generated through a process of organizing, filtering, and prioritizing all the great observations you’ve gathered and translating them into something meaningful—and actionable. In other words, insights are the product of synthesis. At first glance, an insight may seem like it came out of nowhere. But, when you think about it, you realize in hindsight that it makes perfect, logical sense. What happens is that you (sometimes unconsciously) recognize a pattern that enables you to see things in a new way—the kind of thing that makes you slap your forehead and say, “Why didn’t I think of that before?” Albert Einstein put it succinctly when he said insight “comes suddenly and in a rather intuitive way. But intuition is nothing but the outcome of earlier intellectual experience.” Even seemingly mundane observations can yield unexpected, yet logical insights. It’s just a question of learning how.

It’s important to recognize that observations and insights are not the same thing. Observations are raw data, the gradual accumulation of research information that you have consciously and carefully recorded—exactly the way you way you saw or heard it, with no interpretation. Insights are the sudden realizations—sometimes described as “Aha!” or “Eureka!” moments—that happen when you interpret the observations and discover unexpected patterns. Patterns reveal gaps between where people are and where they’d ideally like to be—between their current reality and their desires. Rifts between the way something is now and the way people assume it should be.

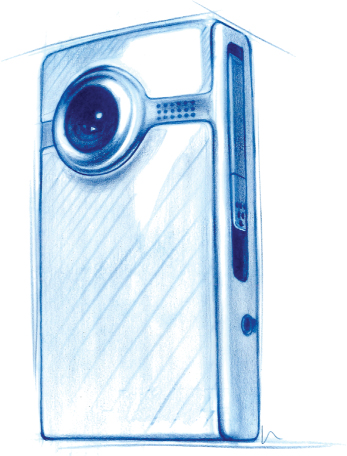

One classic example of a pattern revealing a gap is what’s sometimes called “feature creep,” the constant adding of more and more features to tech products that were already too complicated to begin with. Do you have a video camera? If so, how many of the features do you really use? How many do you really care about? All most people really want is to record, zoom, and upload the video to their hard drive or YouTube.

Consumer electronics company, Pure Digital, saw a way of greatly simplifying life. Home-video cameras were expensive and complicated, and it suspected there might be a place for a much cheaper, simpler video camera. So its team created the Flip Ultra to fill the gap, a video camera that has an On/Off switch, a zoom-in/zoom-out toggle, and a foldout USB adapter. And it runs on ordinary batteries.

The Flip Ultra video camera was created to fill a gap.

Wherever there’s tension (observation), there’s a gap. If you can spot the gap (insight), you can fill the void (opportunity).

Look for What’s Unexpected and Ask, “Why?”

At this point, your insight board should have several observation clusters and themes. Because there’s no way you can focus on the entire board at one time, what you’re doing here is trying to find some good places to start.

Where you start is important, because it can make a big difference in the way you synthesize insights. We all have a tendency to focus on the most obvious information first—the information that confirms our existing knowledge. That’s fine, but if you pay attention only to what’s obvious, chances are that you’re looking for corroboration and not wanting to reverse the opinions you already have. Insights don’t come from looking at the obvious. They usually come from surprising sources, and, more often than not, they come from observations that were completely unexpected. These observations fly under the radar, unnoticed by people close to the situation. John Kounios, a psychologist at Drexel University, describes insight as “an act of cognitive deliberation transformed by accidental, serendipitous connections.”13

Back in 1992, some residents of a small Welsh town called Merthyr Tydfil were participating in a clinical trial of a new angina drug. Unfortunately for the pharmaceutical company, the drug didn’t do much for angina. But, the drug did have a lot of side effects in men, including back pain, stomach trouble, and erections. If everyone at Pfizer had stayed focused on finding an angina drug, it would have stopped the trials and dropped the drug. But, by shifting the focus from the obvious to the unexpected, from primary effects to side effects, it generated the insights that became one of the most successful drugs ever: Viagra.

When you identify something unexpected, spend some time looking for additional observations that may suggest interrelated connections. Then, ask, “Why is this a pattern?” and, “Why is this unexpected?,” and ultimately, “Why is this meaningful?” Asking “why?” encourages you to think through the connections between observations and adds a layer of interpretation.

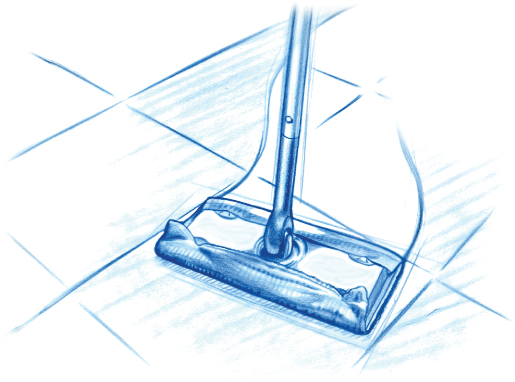

Consider the mundane act of mopping a floor. On an assignment for Procter & Gamble, Boston-based consultancy, Continuum, went to work studying dirt, watching people clean, and cleaning floors themselves. As you’d expect, the obvious thing they observed was that people find mopping a disagreeable chore. However, they also made an unexpected observation—water doesn’t remove dirt all that well. Asking “why?,” they discovered a counterintuitive rift between expectation and result—between what people thought a mop was doing and what, in fact, it was doing. Instead of removing dirt, water tends to slop it around. Dry rags on the other hand, thanks to electrostatic attraction, are far more effective at picking dirt up. Customers didn’t desire mops that work better with water. They just want clean floors.

This insight exposed a gap: an opportunity for waterless cleaning products. The Swiffer brand, as it became known, was an instant hit for P&G, with first-year sales of $200 million. P&G now earns more than $500 million annually from waterless cleaning products, and the insight remains unexpected. “How can it possibly work without water?” consumers often ask.14

The insight for waterless cleaning products was based on an unexpected observation—water doesn’t remove dirt all that well.

Generating insights like this is really a pattern-recognition skill. In other words, you aren’t just reporting what you observe as you observe it. Rather, based on everything you know and have experienced, you’re making connections and interpreting the patterns you see. Insights are new configurations of knowledge that enable you, and others, to see the situation in a different, and often, counterintuitive way—one that draws attention to gaps that had been previously ignored.

Capturing Your Insights

Record your insights in real time and add them to your insight board (using a different colored Post-It note). Keep going until you have covered all of your key themes. Aim for a minimum of one insight per theme.

When capturing and describing insights, the words and phrasing you use matter. Insights often fly in the face of conventional wisdom or expectations. When that happens, use a well placed “but” or “whereas” to draw attention to the contradiction and increase the statement’s impact. For example, here’s how Continuum captured insights on some other projects: 15

• Drivers of high-performance cars are not stressed by high-speed driving but by parking.

• Men who buy premium audio systems like to display them in their living rooms, whereas women would rather hide them behind plants or furniture.

• Customers are not interested in locks per se but in the possessions those locks protect.

Finally, be prepared to take risks with your insights. They don’t have to be unmistakably correct; they have to be thought-provoking. In many research approaches, the pressure to be incontrovertibly right is so strong that there’s no space for intuition and intriguing perspectives. The most important thing to remember is that research insights are not ends in themselves. You’re generating them to feed the opportunities that will put your hypotheses into action.

To summarize: The first purpose of this research is to observe, identify, and record tension points. The second is to cultivate insights that highlight gaps between the way something is now and the way it ought to be. The third is to work out opportunities to fill the gaps.

What Are Your Disruptive Opportunities?

Now that you’ve captured a handful of insights, it’s time to synthesize them into key areas of opportunity. To do that, you need to bring back your disruptive hypotheses—the three wacky and provocative “what if” questions I talked about in Chapter 1.

To recap: The reason you kick off this process with disruptive hypotheses instead of going straight into contextual research is because you must pick apart the existing industry clichés to see things differently. Provocative “what if” questions prepare you to recognize things you didn’t notice before and put research observations together in new ways.

If you skip the hypothesis step, it probably wouldn’t occur to you that there may be other ways of designing the situation you’re focused on that are just as plausible (renting cars by the hour or socks that don’t match, for example).

But, as I said at the start of this chapter, it’s not enough to hypothesize about how something could be disruptive; your hypotheses have to be radical in ways that deliver value to people. And that happens only when you use customer insights to translate your hypotheses into opportunities.

Think of it this way: Hypotheses feed observations. Observations feed insights. Insights feed opportunities.

Moving from Insights to Opportunities

An opportunity has three distinct parts: There’s an opportunity to provide [who?] with [what advantage?] that [fills what gap?]. In our car example, it might look like this:

“There’s an opportunity to provide drivers with ways of being more productive that are safe and optimized for driving.”

To get from insights to opportunities, start by matching each insight to the hypothesis it’s most closely related to. Look for the insights that have the potential to put a hypothesis into effect—something in the insight that suggests that your implied disruption would deliver a key advantage. To continue the car example:

Hypothesis: What if cars were not for driving?

Insight: There’s much more happening in a vehicle than just going for a drive, but cars are not designed to support non-driving activities.

After you find the best pairing, use the relevant insight(s) to work out one really big point of advantage for each of your “what if” speculations. (Renting cars by the hour would deliver flexibility. Miss-matching socks would enable self-expression.)

If you’re in the soft-drink business, for example, and your disruptive hypothesis is that the product should taste terrible, is there an insight that indicates how you can turn that into an advantage? If your hypothesis suggests that your product should be far more expensive than the competitors’, is there an insight that could make that into a good thing?

Back to the car example: The first part of the insight was “there’s much more happening inside a vehicle than just going for a drive.” This came from the observation that drivers currently check email, make phone calls, and use their laptop while in their cars.

If we imagine that cars were not for driving, and ask what else could they be used for, our insight suggests an advantage—people could use cars like an office to be more productive.

Hypothesis: What if cars were not for driving?

Insight: There’s much more happening inside a vehicle than just going for a drive (checking email, making phone calls, using their laptop, and so on).

Opportunity: Provide drivers [who] with ways of being more productive [advantage].

The second thing to work out is “what’s the gap that needs to be filled?” If this isn’t immediately apparent, consider the tension point captured by the insight. If necessary, refer to the four categories I noted earlier:

• Workarounds: Does the insight suggest an opportunity to remedy the underlying problem itself, not just the symptoms?

• Values: Does the insight suggest an opportunity to address a change in what consumers’ value?

• Inertia: Does the insight suggest an opportunity to leverage a habit or break a habit?

• Shoulds versus wants: Does the insight suggest an opportunity to turn wants into shoulds? Or shoulds into wants?

In the car example, the second part of the insight was “but cars are not designed to support non-driving activities.” This came from the observation that drivers do all sorts of non-driving activities in their cars anyway. This reveals a gap: Automobiles have not been designed for how people actually use them in today’s world. So, productivity features optimized for the safety of the driver will address an unmet need.

Let’s see how this example looks when framed in the terms I’ve described in this, and the previous, chapter:

Cliché: Cars are for driving.

Hypothesis: What if cars were not for driving?

Insight: There’s much more happening than just going for a drive, but cars are not designed to support non-driving activities. (Drivers currently use their cars to check email, make phone calls, and use their laptop.)

Opportunity: Help drivers [who] be more productive [advantage] in a way that’s safe and optimized for driving [gap].

Describing the Opportunities

Remember that all of your research activities are done to drive the discovery of opportunities. It’s possible that your opportunities may deviate from your original hypotheses as you work through this definition process. So, you might have to abandon or reframe your original hypotheses to sync them with your insights.

That’s okay. Opportunities are totally context dependent. Too often, we assume that we correctly understand the context we’re hypothesizing about and that all of our assumptions are correct. But, if you’ve discovered an insight that leads you in a completely different direction from where your hypotheses were taking you, go with it. That new direction may be just as valid, and perhaps more effective, because it’s based on a better understanding of the context. Defining opportunities often requires a few backward or sideways steps now and then.

The important point is that your articulation of these opportunities should highlight an unexpected gap, a clear indication of an advantage, and a high-level reference to who it’s for. Make sure it’s customer focused.

After you describe your opportunity in one sentence, support your point of view with some key observations and insights from your research. For the car project, the team supported the “productivity” opportunity with the observation that, “Everyone thought it was a bad idea to be on the phone while driving, but they all did it anyway. A lot.” They fleshed this out with even more observations, such as that drivers view car time as optimal time for making phone calls, and that when they’re making those, they’re generally alone, inside a controlled environment, and have “nothing else to do” (except drive, of course).

As a final example, let’s go through the same process with the Swiffer mop: 16

Cliché: People use mops with water to clean floors.

Hypothesis: What if mops did not use water?

Insight: A common failure of cleaning floors is not a lack of water, but an excess of water. (Water slops dirt around.)

Opportunity: Provide people at home [who] with a faster way to clean floors [advantage] without using water [gap].

Last point: An opportunity is not a solution. You’ve identified an advantage and a gap, but not the means of putting it into effect. Next, what you need are some ideas to execute the opportunity. That’s the focus of Chapter 3.

Think Outside the Socks! The Disruptive Opportunity

As I mentioned earlier, it’s important to immerse yourself in the world of your customers, to try to see how things look from their viewpoint. And that’s just what Jonah and his partners did. They had identified tween girls (ages 8–12) as their core target market, and by asking questions and paying close attention to the answers, they generated a number of observations which led to a key insight: Tween girls see themselves as being somewhere between a child and adult. They consider themselves sophisticated and mature, but they enjoy having fun and are still comfortable just being kids.

This insight suggested a disruptive opportunity—there were socks for kids and socks for adults, but nothing particularly compelling in between. The idea of wearing mismatched socks already sounded like self-expressive fun. If they could ensure that the socks also had a level of mature sophistication and premium quality, they could address a gap in the market.

Use the following list to plan your contextual research and gather your observations:

1. Determine the kinds of information you’d like to gather by making a list of questions.

2. Define the relevant audience: a mix of the target customer population, potential customers, and/or outlier customers.

3. Work out the timing required. Your decision will depend on the size and complexity of your focus, but it should be a rapid immersion: 2-3 hours for a quick informal study, 2-3 days for a longer one.

4. Set up interviews and observations in the context where people use the products and services that are relevant to your situation.

5. Allow for multiple observation sites so you’ll be able to collect rich information across several environments.

6. Do at least two of the following:

• Open-ended interview and observation: Conduct on-site visits in each pre-arranged participant’s place, whether it’s a bank, an office, a supermarket, or a car wash. In addition to interviewing, make observations of the environments they live or work in. Look for implicit tension points in the form of workarounds to problems and the other points just listed. It is also important for you to understand the participant and the environment of the industry you are provoking. Recruit yourself or work with a recruiter,17 develop a research plan, schedule visits, and conduct research.

• Noninvasive observation: Make observations in the context of people’s interaction in public environments. How do people use computers, for example, at an airport gate while waiting for a flight? Unscheduled observations occur in a more ad-hoc manner. Determine your research questions, find locations where the activity takes place frequently, observe, and take photos or video.

• Intercept: Visit a store or public space that’s relevant to your situation, watch the purchase process or general activities, and then approach and speak with people. When fellow customers ask whether someone had a good experience at the store, they often get a much different (and more accurate) answer than the one they would give to the checker (who would probably cheerfully ask, “Did you find everything you were looking for today?”). Your aim is to understand how people make decisions while in their normal flow of interaction with the relevant situation. Determine your research questions, find locations where the activity takes place frequently, approach participants, and ask questions.

Use the following list to organize your observations, make sense of your findings, and generate key insights:

1. Ground your data. Print or transcribe your observations, one per Post-It note. Print key photographs, sketches, or other images you collect.

2. Set up an insight board. Find a surface that’s large enough for you to move, group, and arrange all of your observations and supporting information.

3. Cluster related observations and identify larger themes. Then, describe, in one or two words, the key theme that identifies each cluster. Write the name of the theme on a different colored Post-It note. For example, observations of how drivers use their cars to collect things, keep things handy for an extra side trip, and carry extra things to make a trip more comfortable, can form a theme for “being prepared.”

4. Look for unexpected patterns. Start with the observations that surprise you and search for additional observations that suggest interrelated connections.

5. Generate insights by asking “why?” Interpret the patterns you see, using your best-guess intuition. Look for a counterintuitive rift between expectation and result. (For example, instead of removing dirt, water tends to slop it around.)

6. Capture your insights. Record them in real time and add them to your insight board. Keep going until you cover all of your themes. Aim for a minimum of one insight per theme.

7. Give your insights impact. Use paradoxical phrasing (but or whereas) to call attention to the gap exposed by the insight.

Use the following list to organize your insights into opportunities, and then select one opportunity to pursue:

1. Match insights to your hypotheses. Which insights are related to which hypotheses?

2. Consider the relationship between insights and hypotheses. Look for the advantages that your insights suggest.

3. Group and re-group. Combine the insights in different ways to find the best hypothesis fit.

Use the following list to articulate the opportunity:

1. Describe the opportunity. You should be able to express each opportunity area in a three-part sentence. Confining your statement to one sentence focuses it on the expected advantages of the opportunity rather than the means of putting it into effect. (For example: The opportunity suggests that productivity features optimized for the safety of the driver will be an advantage. But, it stops short of explaining what those productivity features will be or how they’ll be implemented.)

2. Provide the supporting logic. What are the key observations and insights from your research that make it obvious that the opportunity is advantageous? (For example: We observed that drivers currently make use of their vehicles for productivity, regardless of whether the in-car experience explicitly supports those activities or not.)