Chapter 1. The Power of Network-Centricity

“The key is to be able to collaborate—across town, across countries, even to the next cube. ... Global innovation networks help make this happen.”

—Tony Affuso, UGS Chairman, CEO, and President.1

Innovation used to be something companies did within their four walls. Storied organizations like AT&T’s Bell Laboratories, IBM’s Watson Research Center and Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center were the temples of innovation.2 Thousands of researchers and scientists toiled deep within the bowels of large corporations to create the next big thing. Corporations viewed their innovation initiatives as proprietary and secret. And they attempted to hire the best and the brightest researchers and managers to drive basic research and new product development. In fact, any self-respecting organization was afflicted with the “Not Invented Here” (NIH) syndrome—believing that it had the best ideas and the best people, so if it did not invent a certain something, that thing wasn’t worth looking at.

Then the Internet happened. With it came phenomena like the Open Source Software movement, electronic R&D marketplaces, online communities, and a whole new set of possibilities to reach out and connect with innovative ideas and talent beyond the boundaries of the corporation. Even the lexicon associated with innovation is changing, with new adjectives that describe a very different view of innovation—open, democratic, distributed, outside, external, community-led. The changes in vocabulary and metaphors suggest that the shift in the nature and the process of innovation is broad and deep. Consultants, academicians, and mainstream business media have all joined the chorus to liberate innovation from organizational boundaries. Special issues and articles in business magazines with titles such as “The Power of Us,” “Open Source Innovation,” “and “The Innovation Economy” implore managers to reorient and amplify their innovation initiatives by tapping external networks and communities.

But, in the words of the miners in the California Gold Rush in the nineteenth century, is there real “gold in them thar hills”? Or, what exactly can such externally focused innovation deliver? To answer this question, we first need to look at the problems companies are facing in continuing to grow their revenues and profits.

The Quest for Profitable Growth

How the mighty can stumble. Consider Dell Inc., the leading seller of personal computers and accessories. From 1995 to 2005, Dell was a paragon of profitable growth, fueled by its innovative build-to-order manufacturing and direct-to-customer sales business model. During the five-year period from 2000 to 2005, Dell’s revenues grew at 16% per year and its earnings increased 21% per year. The company was widely admired for its ability to drive growth and increase its market share by executing flawlessly on its business model, and staying focused on process innovation. When other companies started imitating its business model, Dell maintained its edge by further refining its business processes to become even more efficient in its operations. However, Dell’s growth engine stalled badly in 2005. In 2006, it missed investor expectations for several quarters in a row, and its stock lost almost half of its value from July 2005 to June 2006. One reason behind the downfall of Dell is that it became too much of a one-trick pony—using the same direct business model for more than two decades, and not innovating enough in terms of new products and new markets. Meanwhile, Dell’s competitors, including Apple Computer and Hewlett-Packard, who placed more emphasis on innovative products and new business models, grew faster and increased their market share at the expense of Dell. Dell’s growth woes are likely to persist for the foreseeable future, and its senior management will be under intense pressure to reignite the growth engine.

Dell is not the only large company facing such growth challenges. Companies such as Kraft, 3M, Sony, Ford, and IBM are all finding it difficult to drive growth. Investors closely monitor the CEOs and senior management of large public companies on their ability to grow the firms they lead. No wonder then that a majority of the CEOs consider growth to be their highest priority—even more than profits. Although growth has always been on the CEO agenda, the perennial quest for growth has become more challenging in the era of global competition and shrinking product life cycles.

In their attempt to jumpstart growth, companies often turn to inorganic growth through mergers and acquisitions (M&A). M&A deals are very appealing to senior managers—they generate an immediate boost in revenues; the hard synergies (mostly financial) are very apparent; and the internal stakeholders (that is, senior managers) have a lot to gain from making the deals. As a result, M&A activity has increased to a fever pitch. In 2005, there were 10,511 mergers and acquisitions involving U.S. companies alone, with an aggregate value of more than $1 trillion—a 28% increase over 2004’s $781 billion.3

However, there is trouble in “M&A land.” Simply put, mergers and acquisitions don’t work as advertised. Most studies and surveys paint a gloomy picture of the after-deal scenario. Between 70% and 80% of the M&A initiatives end up in failures—most of them within the first 18 months.4 Companies generally do well at realizing the hard synergies; for example, consolidating the borrowing, restructuring the taxation, pooling the working capital, purchasing at higher volumes, and so on. The soft synergies—operational consolidation, process improvement, channel merging, technology sharing, staff layoffs, extension of customer base, and so on—are what rarely materialize. Although most M&A failures are blamed on “people” and “cultural” issues, the end result is that such initiatives fail to enhance (and, often contribute to decline in) shareholder value. After the failure, the CEO often exits and a new CEO arrives who starts divesting those previously acquired divisions—and then promptly start acquiring new ones! Like a gerbil in a treadmill, the cycle of acquisitions and divestitures goes on, with the only sure winners being the consultants, lawyers, and investment bankers.

Given the high visibility of many recent M&A failures (remember Time Warner and AOL or Chrysler and Daimler-Benz), many CEOs have changed their tune and now proclaim innovation as the preferred pathway to growth. In a recent CEO survey, 86% of respondents indicated that innovation is definitely more important than M&As and cost-cutting strategies for long-term growth. In fact, many CEOs and senior managers have come to view innovation as their only alternative to achieve sustained growth.5

As Howard Stringer, Chairman and CEO of Sony, recently noted, “We will fight our battles not on the low road to commoditization, but on the high road of innovation.”6

However, despite such public statements about the importance of innovation, when it comes to actual decisions and actions, many companies still take the easy way out—focusing either on cost-reduction initiatives that promise short-term profit increases or on mergers and acquisitions that create an illusion of rapid revenue growth, even if the former is often not sustainable and the latter mostly turn out to be failures. In short, a significant gulf seems to exist between the desire to innovate and the ability to innovate.

An Innovation Crisis?

The ability of firms to innovate is stymied by two factors—the pace of innovation required to maintain and grow profits is increasing, and the productivity of internally driven innovation efforts is decreasing. These two factors are conspiring to create an innovation crisis in large firms.

The “Red Queen” Effect in Innovation

“Well, in our country,” said Alice, still panting a little, “you’d generally get to somewhere else—if you run very fast for a long time, as we’ve been doing.” “A slow sort of country!” said the Queen. “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!”7

Despite having hundreds of in-house scientists and engineers working tirelessly on innovation projects, managers are discovering that their innovation pipelines are not delivering the results they need to sustain growth. Innovation productivity is declining while the cost of new product development is increasing day by day. Investing more dollars into internal R&D efforts does not seem to produce the desired payoffs. For example, Kraft invests close to $400 million annually and has 2,100 employees in its internal R&D unit. Despite such large investments, the company has been discovering its R&D pipeline to be less and less effective in fueling firm growth.8 The story is not much different in many other large firms in both the technology and the consumer product sectors.

On the other hand, the industry cycle times continue to shrink rapidly across the board. For example, in the automobile industry, 48-month development cycles and six-year model life cycles were the norm. But today, concept-to-production times are down to less than 24 months, and industry leaders like Toyota are talking about 12-month development cycles. In consumer electronics markets (for example, cell phone, digital audio player, and so on), product life cycles are often measured in weeks, not months.

Added to this acceleration is the impact of globalization—global markets breed global competitors. Companies such as Samsung from Korea (in mobile phones and televisions), Tata from India (in automotive), and Lenovo from China (in computers) have upped the ante by producing innovative products at significantly lower costs, driving the rapid commoditization in many product categories.

These forces—rapidly decreasing product life cycles, decreasing internal innovation productivity, and global competition—together are creating a Red Queen effect9 in innovation: Companies have to invest more and more just to maintain their market position.

Consider a simple simulation done by Dave Bayless, an entrepreneur and our friend, to understand the crippling effect of shrinking product life cycles on growth. Assuming a company has base revenues of $500 million per year, the simulation illustrates how a 10% annual increase in industry clock speed would necessitate an immediate and sustained increase in the rate of new product introductions of 50% just to maintain that average level of revenue over ten years.10 And this simulation did not even consider the potential negative impact of reduced innovation productivity or the increasing market risk of new products and services—both clearly evident in many industries. Thus, just one factor alone, shrinking product life cycle, poses a critical innovation challenge. On top of that, if the company wants to grow even at a modest 4% or 5% annual rate, the innovation challenge becomes almost insurmountable.

The Limits of Internally Focused Innovation

It is not just the Red Queen effect that defines the limits of internally focused innovation initiatives. There is also the potentially debilitating effect of a myopic “world-view” that companies often come to possess—particularly when their “successful” innovation and growth strategies have been around for a while.

Dell’s direct-to-consumer business model is a good example in this context. As market pressures continue to climb in the personal computer market, Dell’s inability to come up with new business models is what continues to drag down its growth. Dell, to its credit, has started considering new ways of doing business and entering into new product categories and markets—but these efforts haven’t been met with much success. Granted, business model innovation is not easy. But it is Dell’s ingrained perspectives derived from operating its current business model for a long time that makes such business model innovation doubly difficult. Over time, organizations become prisoners of what they know, especially when they have met with sustained success. They fail to see beyond their limited view of the world.

This limited world-view is becoming more dangerous in the turbulent and dynamic business environment that we find ourselves in. In many industries such as consumer electronics, automobiles and software, products have become more complex in terms of their features, their underlying technologies, and their design. Therefore, the knowledge and skills required to design and develop new products and services have become much more diverse and more demanding. Innovating such new products and services thus calls for not only a command of diverse sets of knowledge and expertise but also the ability to make non-obvious connections between such diverse knowledge bases. This feat is very difficult to pull off inside the four walls of any firm, no matter how large.

Clearly, throwing more and more money at the internal innovation engine is not the most efficient way to address the innovation crisis. Doing more of the same can only result in incremental improvement in innovative output. What is really needed to overcome this crisis is a significant increase in the company’s innovation reach and productivity—only such an increase will translate into a dramatic shift in innovation output of one or more orders of magnitude. And to gain such increases in reach and range of innovative ideas, companies need to broaden their innovation horizons by looking outside for innovative ideas and technologies.

Consider the case of Kraft. Profits fell 24% in the time period from 2003 to 2005. Top-line growth stalled, and net income in 2005 was $2.63 billion, down from $3.48 billion in 2003. The company that came up with blockbuster products such as Oreo cookies, Miracle Whip dressing, and DiGiorno pizza is hungry for ideas. It is not lacking any internal R&D infrastructure. Kraft has an extensive internal R&D setup, with thousands of talented researchers on staff. However, internally focused innovation efforts are not delivering the goods. So Kraft has turned outwards in its quest for ideas: The company is inviting unsolicited ideas from its customers or for that matter from anybody who visits its Web site and submits ideas. Whether putting such an invitation for ideas on the company Web site is the right approach is debatable, but what is less arguable is the need to start looking outside. Indeed, the limits of internally focused innovation are well illustrated by Kraft’s radical departure from past practice. As Mary Kay Haben, senior vice president at Kraft, noted, “In the past we would have said, ‘Thank you, but we are not accepting ideas.’”11

The imperative to look outside is not limited to the consumer product sector. Consider Merck, a giant in the pharmaceutical industry. Merck has traditionally been an internally focused innovation organization. However, after a string of failures and a very lackluster R&D pipeline, it made a strategic shift toward looking outside for innovation—specifically, to partner with smaller firms with innovative ideas. Merck’s R&D chief, Peter Kim, made it clear that the company’s own labs are insufficient to replenish its pipeline for the future, and three years or so back embarked upon a more collaborative and open innovation agenda. Although the results of this approach will likely take years to become evident, the initiative is well underway. Compared to 10 outside alliances in 1999, Merck has entered into 141 such deals between the years 2002 and 2004—an average of 47 each year. And in 2005, Merck reviewed more than 5,000 such external collaboration opportunities.12

Overcoming the Crisis: “Looking Outside”

The opportunities for companies to “look outside” for innovation are increasing day by day. As we noted previously, the Global Brain is rich and diverse—a large number of innovative firms as well as a large pool of innovative people exist in different parts of the world whose knowledge and creativity can be leveraged by companies. Moreover, new types of innovation intermediaries and new technological infrastructure (for example, the Internet) have made tapping into such global networks of inventors, scientists, and innovative firms easier than ever before. Thus, the imperative for sourcing external innovation is matched by the rapidly expanding horizon of innovation opportunities.

Former Sun Chief Scientist, Bill Joy, noted several years back that “most of the smart people in the world don’t work for your company.” True enough, but increasingly those smart people in other parts of the world represent a global innovation opportunity waiting to be tapped.

This is mirrored in companies, such as by P&G’s recent innovation initiatives. As Tom Cripe, Associate Director of P&G’s External Business Development group, recently noted:

“We want to grow efficiently. And at the size we are, it’s just not possible to do it all yourself. And even if it was it’d be lunacy to attempt it. There are just too many smart people out there. If we have to grow at the rate we want to, we have to add incremental business of billions of dollars ... It took us 100 years to get here and we now have to do in a few years what we did in 100 years. Even if we could, it would be expensive. And so we’ve been able to increase our innovative output while reducing our spending as a percent of sales because we’re multiplying it by all the people we’re partnering with. So the reason for ‘looking outside’ is to grow most effectively by drawing on the very best ideas out there, rather than trying to compete with everybody.”13

This message has come through in several other forums, too. For example, the Council of Competitiveness published the National Innovation Initiative report in 2004. This report focused on the implications of globalization for the national innovation agenda for the United States. Among other trends, the committee identified the effective pursuit of highly collaborative innovation as of utmost importance for the U.S. economy. As the report notes, “Innovation itself—where it comes from and how it creates value—is changing:

• It is diffusing at ever increasing rates.

• It is multidisciplinary and technologically complex and will arise from the intersection of different fields.

• It is collaborative, requiring active cooperation and communication among the scientists and engineering and between creators and users.

• Workers and consumers are embracing new ideas, technologies, and content, and demanding more creativity from their creators.

• It is becoming global in scope—with advances coming from centers of excellence around the world and the demands of billions of new consumers.”14

The key findings of the committee also reflected how the global connectedness and the scale of collaborative innovation will demand the development of a more diverse workforce that is able to communicate and coordinate innovation activities across organizational and geographic boundaries.

Similarly, IBM has been conducting a global conversation on innovation that it calls the Global Innovation Outlook (GIO). The most important finding from IBM’s GIO conducted in 2005 and 2006 was that innovation is more global (anyone and everyone can participate without geographical barriers), more multidisciplinary (innovation requires a diverse mix of expertise), and more collaborative (innovation results from entities working together in new ways).15

To enjoy the benefits of such a rapidly expanding horizon of innovation opportunities, companies would need to make a gradual shift from innovation initiatives that are centered on internal resources to those that are centered on external networks and communities—that is, a shift from firm-centric innovation to network-centric innovation. However, the question remains: Will such a shift address the innovation crisis outlined earlier? In other words, will a network-centered innovation strategy deliver gains that are orders of magnitude higher in innovation reach, range, and effectiveness?

To understand the promise of network-centric innovation, we need to consider its foundational theme or premise—namely, the concept of network-centricity. The concept of network-centricity has very deep roots and very broad applicability. Before we discuss how networks can enhance innovation, let us examine how network-centric capabilities are transforming several other domains.

The Power of Network-Centricity

The university that one of us works at has a library with close to 500,000 books on its shelves. Considering the number of students—around 7,500—it is not a large acquisition. However, the library is part of a network of 13 other university libraries in the area—a system called ConnectNY. The total number of books in the ConnectNY network is 10 million. Each member of the ConnectNY network can request books from any other member library, and if the book is available, it is delivered by a private courier (who travels between the different member libraries) within three to four business days. Thus, in effect, by becoming a member of the ConnectNY network, the library has increased its acquisition by twentyfold—from 0.5 million to 10 million.

Consider another simple example—the task of replenishing a vending machine. A service truck can visit each and every vending machine and then find out whether it needs any servicing or not. This method creates inefficiency because there is no way for the person making the rounds to know whether he needs to replenish a specific machine and what exactly the machine is short of. Imagine if the vending machine could “talk” to the service person over an information network and inform him in advance if it was running out of a specific food or beverage item. This is what Vendlink LLP, a N.J.-based vending service company, has done in Philadelphia. It created a wireless network that integrates information from all the vending machines in the area and produces a servicing plan that optimizes the logistics involved.

Even toys can be made smarter after they are connected to a network. In 1997, Fisher Price and Microsoft created the ActiMates Interactive Barney. By itself, ActiMates Interactive Barney is a cute, purple stuffed animal. But the real fun begins when the toy is used with either of two add-on devices: a TV Pack, which adds a radio transmitter to the user’s TV/VCR; and a PC Pack, which does the same to a computer. The toy enables children to improve their vocabulary or language skills. The company also created a network from which the “lessons” can be downloaded into the toy. As the child gets older, parents can connect the toy to the network, download the appropriate components, and thereby extend its use.

These simple examples reflect the essence of network-centricity: the emphasis on the network as the focal point and the associated opportunity to extend, optimize, and/or enhance the value of a stand-alone entity or activity by making it more intelligent, adaptive, and personalized. It should be no surprise, therefore, that the concept of network-centricity has permeated many aspects of our contemporary world and daily-life—ranging from warfare and military operations to social advocacy movements. Let us start with network-centric computing.

Network-Centric Computing

In the field of computer science, the shift from host-centric computing to distributed or network-centric computing has relatively old roots. The concept of distributed computing, pioneered by David Farber in the 1970s at the University of California,16 evolved into what is now called network-centric computing or grid computing.

Grid computing relates to the ability to pursue large-scale computational problems by leveraging the power and unused resources of a large number of disparate computers (including desktop computers) belonging to different administrative domains but connected through a network infrastructure.17 The essential idea behind grid computing is to solve computing-intensive problems by breaking them down into many smaller problems and solving these smaller problems simultaneously on a set of connected computers. The parallel division of labor approach can result in very high computing throughput, often more than a supercomputer. Further, this throughput can be achieved at a cost that is significantly lower by exploiting the relatively inexpensive computing resources available at remote locations. And the network-centric computing architecture also is far more flexible, because remote users can decide moment-to-moment how much computing power they need. The promise of grid computing—high computing power combined with low cost and high operational flexibility—is spurring many applications in commercial as well as non-commercial contexts, including financial modeling, weather modeling, protein folding, and space exploration.18

Network-Centric Warfare

Network-centric warfare (NCW) is a relatively new theory or doctrine of war developed primarily by the United States Department of Defense.19 This emerging theory indicates a radical shift from a platform-centric approach to a network-centric approach to warfare.

The basic premise of NCW is that robust networking of geographically dispersed military forces makes it possible to translate informational advantage into warfare advantage.20 Higher levels of information sharing among the units enhance the extent of “shared situational awareness.” In other words, through information sharing, every unit—from infantry units to aircraft to naval vessels to command centers—“sees” the sum of what all other units “see.” This shared awareness facilitates self-synchronizing forces, virtual collaboration, and other forms of flexible operations. The value proposition for the military is a significant reduction of combat risks, higher order combat effectiveness, and low-cost operations.21 Although there is still significant debate about how soon and to what extent the benefits of NCW can be realized, several countries, including Australia and the UK, have embraced the basic tenets of network-centric warfare.

Network-Centric Operations

The term network-centric operations (NCO) was originally applied to the field of logistics and supply chain management in business enterprises. The term “value nets” or “value networks” has also been used in this context. However, more recently, NCO has gained a broader interpretation and is often used interchangeably with NCW in the defense and military areas.

In the supply chain management context, NCO signifies establishing dynamic connections between the enterprise, suppliers, customers, and other partners to deliver maximum value to all the entities concerned.22 It involves integrating enterprise information systems (for example, ERP and CRM systems) with external partners’ systems and processes to enhance the information flow and “sense and respond” capabilities. Whereas traditional supply chains emphasize linear and often inflexible connections, network-centric operations or value nets focus on establishing varied, dynamic connections that deliver both efficiency and agility to the enterprise. Supply chain–focused software companies such as SAP, i2 Technologies, and IBM have adapted these concepts to create applications that support such network-centric supply chain operations.

Network-Centric Enterprise

The concept of network-centric enterprise (NCE) owes its origin to the concept of business ecosystems and virtual organizations. It involves establishing an “infostructure” that connects the different partners in a company’s business ecosystem and supports the different value creation processes. As such, the concept of NCE is also closely related to NCO.

Companies such as Wal-Mart, Cisco, and Toyota have considerable experience in deploying and operating such a network-centric enterprise. For example, Cisco has evolved its organization into what it calls the “Networked Virtual Organization” (NVO) in its manufacturing operations.23 Similarly, Toyota has used the NCE model to improve its just-in-time inventory management. The NCE (or NVO) model has three core tenets.24 First, it puts the customer at the center of the value chain and emphasizes the need to respond rapidly to customers’ needs. Second, it calls for the enterprise to focus on those core operations or processes where it adds most value and to outsource or turn over all other operations to multiple partners. Finally, the model requires significant process, data, and technology standardization to enable real-time communication and synchronization across organizational boundaries. Overall, the network-centric enterprise model implies significant strategic and operational agility for an enterprise, thereby enhancing its ability to thrive in highly dynamic markets.

Network-Centric Advocacy

The concept of network-centricity is also becoming evident in the domain of social advocacy movements. Social advocacy groups have realized that the basic tenets of network-centricity can be adopted to enhance the reach, speed, and overall effectiveness of social movements.25

Network-centric advocacy (NCA) signifies a critical shift from the direct engagement and the grassroots engagement models of social advocacy to a more network-centered model wherein the individual participates as part of a coordinated network.26 In NCA, individuals and groups that are part of the network rapidly share information on emerging topics and identify “ripe campaign opportunities.” The ability of the network to scale up in terms of resources, expertise, and overall level of public support brings sharpened focus and enhanced visibility to the campaign. Network-centric advocacy provides several advantages: speed of campaign, ability to pursue multiple campaigns with few resources, and ability to rapidly abandon losing efforts. All this brings an element of unpredictability that lowers the ability to counter such social campaigns effectively.

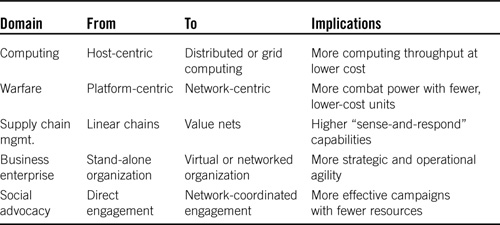

We summarize the promise of network-centric concepts in Table 1.1. These examples suggest that, although the concept of network-centricity has found considerable application in diverse domains, all these applications have a common thread in terms of outcomes—greater power, speed, flexibility, and operational capabilities delivered at a lower cost using diverse resources that are spread out geographically. These benefits are the very ones we seek as we examine the appeal of network-centricity in the domain of innovation.

Table 1.1. Evidence of Network-Centricity in Different Domains

Network-Centricity and Innovation

To apply a network-centric perspective to innovation, we formally define network-centric innovation (NCI) as an externally focused approach to innovation that relies on harnessing the resources and capabilities of external networks and communities to amplify or enhance innovation reach, innovation speed, and the quality of innovation outcomes.

Network-centric innovation features principles that are analogous to the examples we mention from other domains. We define these principles in the next chapter. But first, let us look at the evidence of the power of networks to enhance innovation in a variety of industries and markets.

Perhaps the most celebrated example of networked innovation is the Open Source Software (OSS) movement, and its most famous product is Linux, the fast-growing open source operating system that was developed and is continually enhanced by a networked community of software developers. The first release of Linux Kernel, version 0.01, was in September 1991, and it consisted of 10,239 lines of code. By April 2006, version 2.6.16.11 had been released with a whopping 6,981,110 lines of code. In this 15-year period, thousands of programmers spread across the world contributed to the development and release of more than a hundred versions of the Linux Kernel. In fact, within one year—from early 1993 to early 1994—15 development versions of the Linux Kernel were released. Such a rapid release schedule is unheard of in the commercial software world, and it reflects the innovative power of the global Linux community.

A more formal comparison of the development effort between Red Hat Linux version 7.1 (a distribution version) and a similar proprietary product was done in 2001.27 Red Hat Linux 7.1 contained more than 30 million source lines of code and reflects approximately 8,000 person-years of development time. If this version were developed in a proprietary manner (that is, inside an organization such as Microsoft or Oracle) in the United States, it would have cost approximately $1.08 billion (in year 2000 U.S. dollars).

To provide further evidence of the awesome power of such innovative communities, consider Red Hat Linux version 6.2, which was released just a year earlier in 2000—it had only 17 million lines of code and represents 4,500 person-years of development effort ($600 million in comparative cost). Thus, version 7.1 was approximately 60% more in terms of size and development effort. In one year, the open source community’s innovative contributions increased two orders of magnitude—an impossible feat in a conventional proprietary software development initiative.

The creative power of networks and communities is being felt in other domains, too. Consider the community-based encyclopedia called Wikipedia. This online encyclopedia was launched in January 2001, and through the collaborative efforts of tens of thousands of contributors, it swiftly became the largest reference site on the Internet. As of July 2007, Wikipedia had more than 75,000 active contributors working on more than 7,704,000 articles in more than 250 languages. Debate is ongoing regarding the reliability and accuracy of Wikipedia (for example, a peer-reviewed study published by the prestigious journal Nature found that Wikipedia is comparable to the hallowed Encyclopedia Britannica in terms of accuracy,28 while other studies have shown just the opposite). What is undeniable, however, is the creative power of the community that feeds Wikipedia’s exponential growth.

Another example is the world of open source or citizen journalism. The first open source newspaper is OhmyNews—a South Korean online newspaper established in February 2000. The majority of the articles in the newspaper are written by its readers—a community of approximately 41,000 citizen reporters. As a citizen newspaper, OhmyNews exercised considerable influence during the South Korean presidential elections in 2002.29 An International edition (in English) of OhmyNews was launched in February 2004 with 1,500 citizen reporters from more than 100 countries.

Global networks are also turbo-charging scientific research in the life sciences and material science industries. A well-known example of an electronic R&D network is InnoCentive, a global community of scientists that helps large companies seek solutions to their R&D problems by sourcing solutions from scientists around the world. InnoCentive maintains a community of scientists, in fields as diverse as petrochemicals and plastics to biotechnology and agribusiness, from approximately 170 countries. To understand the power of this network, consider the case of Eli Lilly, which had an R&D problem in the area of small molecules that its internal R&D organization had spent more than 12 person-months of work and failed to solve. Eli Lilly posed the problem on the InnoCentive Web site in June 2003. In less than five months after posting it on InnoCentive, Eli Lilly had a solution in hand—a retired scientist based in Germany had found a solution that had eluded Eli Lilly’s internal team of researchers.30 Through InnoCentive, Eli Lilly had effectively increased its reach to approximately 30,000 scientists and researchers who were members of the InnoCentive forum. Other examples from InnoCentive and similar “Innomediaries” suggest that the innovative power of communities can translate into orders of magnitude improvements in innovation speed, cost, and quality.

Perhaps no other company illustrates the power of network-centricity as well as P&G. The company’s aggressive partnership with external innovation networks has translated into highly commendable results. R&D productivity has increased by nearly 60%, innovation success rate has more than doubled, and the cost of innovation has fallen significantly.31

These and other scattered examples of the creative power of the Global Brain have encouraged more and more companies to reorient their innovation initiatives to a more collaborative, network-centered approach. However, as most CEOs and senior managers would readily admit, harnessing this innovative power is something that is “theoretically easy” but “practically hard to do.”32

Let us briefly examine these broad challenges now.

Challenges in “Looking Outside”

Organizations embarking on a network-centered innovation strategy are likely to be faced with different types of networks and communities with different types of innovation opportunities. The three broad sets of challenges that companies will likely face are mindset and cultural challenges, contextualization challenges, and execution challenges.

Mindset and Cultural Challenges

Most large companies have considerable experience in partnering with a relatively small set of carefully identified firms—joint ventures, technological agreements, licensing agreements, and so on. However, when it comes to innovation collaboration on a greater scale—for example, a larger number and geographically more widely dispersed set of partners—most companies have limited experience. The first critical issue that senior managers will need to address relates to the broader implications of adopting such a network-centered approach to innovation. How should the organization view such collaboration opportunities? How can senior managers ensure a coherent set of innovation strategies that capture both external opportunities and internal capabilities? What type of broad framework or mindset should be developed that reflects the organization’s intent to collaborate with outsiders and defines the broad parameters for such collaboration? And how should senior managers communicate and encourage other members of the organization to adopt such a mindset?

For companies such as 3M, DuPont, and Kodak with a history of significant internal achievements and with a vast array of resident scientists and technical specialists, the dominant threat is the feeling of “We know everything and everyone.” This “Not Invented Here” (NIH) syndrome is a serious barrier to acceptance of new ideas from outside the company. The cultural shift needed to overcome the NIH syndrome and to adopt a collaborative mindset is significant. IBM has acknowledged the simple fact that to partner with open source communities and other such communities of creation, it needs to let go of some of the control it has traditionally exercised in all of its innovation initiatives. Indeed, a recent book by Linda Sanford, one of IBM’s senior executives, succinctly captures this spirit through its title, Let Go to Grow.33 Although such a cultural shift might be easy to identify, achieving it in an organization—especially a large organization with a long history of success—is very challenging.

Contextualization Challenges

The second set of issues involves understanding the landscape of network-centric innovation and relating it to the firm’s own unique innovation context.

It is evident that companies such as IBM and P&G have succeeded to different extents in leveraging innovation networks. For example, IBM has subscribed to the open source model and has invested significant resources to align its innovation initiatives in many of its product and service areas with the open source model. Similarly, P&G has garnered significant visibility through its Connect+Develop initiative to partner with external innovation networks such as those offered by InnoCentive and Nine Sigma.

Although these examples indicate specific approaches to a network-centered innovation, they are not the only approaches. The multiplicity of approaches raises many questions: Is there a systematic way to identify and analyze the different approaches (or models) of network-centric innovation? What are these different approaches? How should an organization evaluate and select the most appropriate approach vis-à-vis its particular context? Further, should an organization assume a lead role or a non-lead role in such a collaborative arrangement? What types of internal projects would be ripe for such a collaborative approach? All these issues relate to contextualizing the opportunity offered by the external innovation network or situating the opportunity in the company’s particular market and organizational context.

Execution Challenges

Finally, the third set of issues relates to the actual implementation of collaborative innovation projects. When an appropriate network-centric innovation opportunity has been identified, how should the organization go about executing it? How should the organization prepare itself for network-centric innovation? What are the types of capabilities and competencies that the organization would require? How should the organization integrate its internal and external innovation processes? What types of licensing and other value appropriation systems should it employ? What is the appropriate set of metrics that it should use to evaluate its performance in such collaborative innovation projects?

The preceding three sets of issues—mindset and cultural, contextualization, and execution—represent the type of practical issues that most CEOs and senior managers need to address in order to be successful in championing and executing their external network-centered innovation initiatives. Because these challenges originate from the richness and variation that is present in the network-centric innovation landscape, we continue our discussion by examining the different “flavors” of network-centric innovation.