Chapter 3. The Four Models of Network-Centric Innovation

When you last saw a movie or a documentary on your TV, did you wonder how it was made? Probably not—because we assume that all movies are produced in more or less the same way. Here is the typical production process: A film production studio like Miramax Films acquires the rights to a movie script and decides to produce the movie. Then the studio looks for a director for the movie as well as the lead cast members. After these key people are lined up, other cast members are selected. In parallel, the studio signs up other specialists, including people who do the lighting, catering, select locations, and so on. When the production starts, these specialist service providers are called upon as needed. The studio’s role is to coordinate the activities of all the participants. Although the studio uses the movie script to broadly define the theme and the budget of the film, it tends to leave sufficient leeway for creative input from the movie team, including the director, the actors, the cinematographer, the make-up artists, the special effects team, and the film editor. After the movie is completed, the studio contracts with the distributor (for example, Sony Pictures) who in turn works with exhibitors (for example, AMC Theaters) to distribute and market the film. The studio also ensures that revenues that the movie produces from the theatrical, video, international, cable, and other channels are shared among the participants in the production and distribution, based on contractual terms.

That’s the conventional model for movie production—where a central player (the studio) defines the context for the movie and orchestrates the production activities. However, this isn’t the only model for movie production. In recent years, several interesting new movie production approaches have popped up.

One approach is the antithesis of the traditional studio production—a model of film making in which there is no single, dominant player like a movie studio. Instead, all the participants in the production come together to provide the direction and the coordination for producing the movie. The script for this model could be “Open Source Meets Hollywood!” Consider the case of a British film project called A Swarm of Angels, which has the objective of attracting 50,000 people to collaboratively create a £1 million film.1 A preliminary movie script or a story sketch is posted on an online forum. All the members of the online forum are then invited to contribute to the further script development, production, and distribution. The project director is a Brighton-based digital film pioneer, Matt Hanson, who conceived the idea. The project has three stages: Fund (collect initial funding from members); Film (develop the script and execute pre-production/production/post-production); and Flow (market and distribute the film; create spin-off materials, and so on). Through a dedicated online forum (called Nine Orders), members are invited to contribute £25 each and officially become collaborators on the project. Why should anybody contribute money to such an “open” project? A collaborator can become involved in the creative process of making the feature film—right from writing the script to making the movie to marketing and distribution. The movie is made using digital techniques and the finished film is shared or distributed worldwide on a Creative Commons license that allows free downloading and viewing, free sharing, and free remixing. Currently, two sci-fi-based scripts, titled Unfold and Glitch, are under production.

Yet another model for movie production features a central player like a movie studio, but the creative contributions come from a community of contributors. In this model, the central entity markets and distributes the content, but the content itself emerges organically from the community. Unlike the traditional movie studio production model, there is no predefined theme, script, or director. In fact, production occurs in reverse—the audience produces the movie content, rather than the studio producing the movie and marketing it to the audience.

An excellent example of this “reverse” production model is a media startup firm called Current TV (www.current.tv) that is the brainchild of former U.S. Vice President Al Gore. Gore and his business partner Joel Hyatt founded a media company called INdTV with the objective of offering an independent voice for a target audience of people between 18 and 34—a highly prized target audience in the entertainment industry. The original intent was to provide this audience with a forum to “learn about the world in a voice they recognize and a view they recognize as their own.”2 INdTV acquired a channel from the Canadian network NewsWorld International (a part of Vivendi Universal) for a reported $70 million.3 In April 2005, Gore and Hyatt changed the name of the network from INdTV to Current TV. Programming on Current TV was launched on August 1, 2005 in the U.S. (as of July 2007, it was available in approximately 30 million homes nationwide) and on March 12, 2007 in UK and Ireland.

Most of Current TV’s programming features short-duration videos or “pods” that are anywhere from three to seven minutes. The videos are submitted by the viewers themselves—Current TV calls this programming Viewer Created Content or VC2. Viewers are invited to submit their videos for potential broadcast and the company decides which videos it will broadcast on its cable channel. After a video is selected for broadcast, Current TV buys exclusive rights for the video using a tiered pricing structure (payments range from $500–$1,000). Current TV engages viewers in the selection process by asking them to vote on the videos. These viewer ratings decide whether a video is shown again or not. More recently, Current TV extended its strategy to get its viewers involved in creating advertisements for the Current TV program sponsor companies. These viewer-created ads also carry compensation up to $1,000. If the ads are good enough for use elsewhere, creators can get up to $50,000 from the sponsor company.

In the Current TV model of production, the creative output (pods) of independent contributors is acquired and commercialized (broadcast) using a proprietary infrastructure (the Current TV network channel), and the company owns the rights to the content. The incentives for contributors, according to the company, are three-fold—cash, fame, and creative freedom.4

Yet another model of filmmaking takes a different approach to both the production process as well as to the ownership of the output. In this model, the participants are given the building blocks to make a movie, and are then allowed to create, distribute, and view the resulting movies as they see fit.

To see how this innovative model works in practice, consider the example of MOD Films, a new-generation film company. MOD Films was founded by Michela Ledwidge, a British-based media producer, in 2004. The business model of the company involves producing a regular movie and then offering it to the global audience over the Internet in a form malleable enough to allow them to edit, modify, or remix it to suit their taste. As Wired magazine noted, MOD Films offers “a massively multiplayer online movie.”5 The first such film is Sanctuary—a ten-minute virtual reality sci-fi film shot in Australia in 2005. The film is about a girl, her computer, and a mysterious murder. The original film, released under the Creative Commons license, provides a story framework that the audience can play with—they can disassemble and reassemble materials themselves to create their own interpretation of the story.6 And, the resulting output will also be available under the Creative Commons license. Sanctuary is distributed as DVD-Video as well as in the HD Video format along with a vast library material. Specifically, more than nine hours of production footage and 90 minutes of sound effects and dialog along with storyboards, still photos, and so on are available for viewers who have subscribed to the online forum maintained by MOD Films.7 Viewers can play around with these cinematic elements using a downloadable software tool called Switch that the company provides. More films are on the anvil including The Watch (a drama) and Extra Fox (a comedy).

These four models for movie production are very different in terms of how they are organized, how the process works, and who owns the output. But they have something in common—collaboration among a network of contributors to create an innovative product. More importantly, these models from the entertainment industry are examples of emerging innovation models that lie at the confluence of social or commons-based production methods and hierarchical/market-based production methods. As such, they are harbingers of the network-centric innovation approaches that we are likely to see in the mainstream business world.

Indeed, the entertainment industry has always been a trendsetter in managing and organizing creativity. In a classic article published in 1977 in the Harvard Business Review, Eileen Morley and Andrew Silver described a film director’s approach to managing creativity and distilled a set of wonderful insights for business managers.8 Over the next three decades or so, several of those concepts and practices based on successful film projects from Hollywood have found their way into the business world.9 And, as the preceding examples indicate, the film and the TV industry continue to pave the path in managing innovation and creativity.

Framing the Landscape of Network-Centric Innovation

Taking inspiration from the entertainment industry, let us consider some of the common themes that emerge from the different models of movie production, and how these themes help us to frame the landscape of network-centric innovation in the movie industry and beyond.

When we compare the traditional model of film making with the one followed by Current TV, we note that there is no predefined theme or script for the movie. Even though the studio still calls the shots in terms of what gets aired, the content of the movie is not controlled by the studio. Instead, it emerges as a result of the collaboration among the contributors. Although script-driven movies and documentaries still form the majority of the output from the industry, examples like Current TV suggest the rise of audience-defined content, where consumers take on the role of producers.

Initiatives like the Swarm of Angels go even further, in that the studio plays an even lesser role—that of an enabler and the facilitator of collaboration among individual contributors. In this model, individual contributors exercise greater influence on all or some aspects of filmmaking. Another example of this type of initiative is the Echo Chamber Project, an experiment in documentary production. The Echo Chamber Project is an investigative documentary about “how the television news media became an uncritical echo chamber to the executive branch leading up to the war in Iraq.”10 The project, led by Kent Bye, a documentary filmmaker based in Winterport, Maine, involves a collaborative editing process wherein the lead creator provides a preliminary set of video segments and other collaborators help in categorizing the video segments into different thematic clusters and creating the sequence (storyline). The edited sequences are then exported for final production.

The emerging models and trends in the movie industry illustrate two key dimensions of creative endeavor along which we see change happening. The first dimension relates to the nature of the movie itself—that is, how the overall storyline and content of the movie is defined and how it evolves. The second dimension relates to the structure of the network of contributors to the project; that is, how the talent comes together and shares in activities related to producing, marketing, and distributing the movie.

Generalizing these dimensions to the broader innovation context, we can think of two key dimensions in organizing innovative efforts—the nature of the innovation and the nature of the network leadership. These two dimensions help us to structure the landscape of network-centric innovation. We now explore these two dimensions in more detail.

The Dimensions of Network-Centric Innovation

Structure of the Innovation Space

Different types of projects can be pursued collaboratively in innovation networks. As you saw in Chapter 2, “Understanding Network-Centric Innovation,” some of the projects involve making well-defined modifications or enhancements to existing products, services, or technology platforms. In other projects, the innovation space tends to be less defined and the outcomes of the innovative effort are not well understood at the outset.

Based on this, we can think about the innovation space as a continuum ranging from “defined” on one end to “emergent” at the other end (see Figure 3.1). On the defined end of the continuum, the definition might occur around a technology platform or a technology standard. Such is the case of AppExchange, the development platform created by Salesforce.com to harness the creative efforts of independent software developers. The innovation space can also be defined by dependencies created by existing products or processes. For example, Ducati engages its customers in innovation primarily to generate product improvement ideas for its existing products. Similarly, 3M’s engagement with NineSigma.com was defined in terms of the properties of the adhesive material that the company was seeking. In all these examples, the innovative efforts are defined and limited by existing products, processes, or technology platforms.

Figure 3.1. Dimensions of network-centric innovation

At the other end of the continuum, the structure of the innovation space can be less defined and more uncertain. Although the broad contours of the innovative space might be specified or known—for example, the target market for a new product or service or the existing commercialization infrastructure—there might be fewer restrictions on the nature or process of the innovation. For example, when Staples looks around for innovative ideas, it is seeking new product concepts for the office supplies market. Similarly, in the Open Source Software arena, many of the projects relate to developing totally new software applications—whether it be developing a new development tool or developing a new operating system.

Another way to understand this continuum is to think about its implications for capabilities and knowledge. The more well-defined the innovation space is, the more the focus on exploiting an existing knowledge-base or leveraging existing technologies. On the other hand, the more emergent the innovation space, the more the emphasis on exploration of opportunities in the innovation space and on making creative connections among disparate knowledge domains.

Now, consider the second dimension—the structure of the network leadership.

Structure of the Network Leadership

An innovation network—whether it is an open source community, an electronic R&D marketplace like NineSigma.com, or an ecosystem of technology firms as in the case of Salesforce.com—consists of a set of independent actors with varying goals and aspirations, diverse resources and capabilities, and different business models.

For all these entities to play together in the innovation initiative, there has to be a mechanism to ensure some coherence among their activities, capabilities, and aspirations. This mechanism can go by different names—network leadership, governance, or management. Whatever the precise term, the essence is the need for a mechanism that can provide the vision and direction for the innovation and establish the rhythm for the innovation activities.

Thus, the name we give to the second dimension—the Network Leadership—captures this governance aspect.

Network leadership can be thought of as a continuum of centralization, with the two ends being centralized versus diffused. At the centralized end of the continuum, the network is led by a dominant firm that leads the network. Leadership may be exercised in different ways—envisioning and establishing the innovation architecture, making the critical decisions that affect or shape the nature and the process of innovation, and defining the nature and membership of the network itself. For example, in its technology ecosystem, Salesforce.com provides the leadership by establishing and promoting the technology platform and by facilitating the activities of its external developers.

At the “diffused” end of the continuum, the leadership tends to be loosely distributed among the members of the network. All members of the network share responsibility for leading the network. For example, many Open Source Software projects have a democratic leadership structure wherein the different members of the community share the decision-making powers.

To further understand the distinctions between these two ends, think about the concept of the core and the periphery in networks. The core of a network can be thought of as one or more members of the network who are connected to one another more closely and form the central part of the network. The periphery consists of those members of the network who have limited ties with other members of the network and are more distant from the center of the network.11 For example, consider your own social network. A small set of people forms the core of your social network. These people might include your immediate family, your close friends, and your colleagues. Then there are more casual acquaintances, your relatives and distant family members, the people at your workplace who interact with you, and so on who form the periphery of your social network.

As we move from the left to the right on the continuum of network leadership, we think about innovation networks that have a clearly defined core with a single dominant firm to networks where the core and periphery are less well defined or where the core consists of all or most of the members. For example, at the extreme left, we might consider networks such as Microsoft .NET or Intel’s microprocessor platform network—contexts where a single firm forms the core of the network, provides the leadership, and makes all the key innovation decisions. As we move toward the center, we think of networks such as IBM’s Power chip innovation alliance (www.power.org) wherein IBM forms the core of the network but shares more decision-making rights with other members of the network. As we go further to the right, the core might consist of more than one member, and at the extreme, the core might include most or even all of the members of the network. For example, Open Source Software projects have leadership structures that lie at different points on the right part of this continuum.

Introducing the Four Models of Network-Centric Innovation

The two dimensions—innovation space and network leadership—when crossed together, define four archetypical models that help structure the landscape of network-centric innovation. With a bow to the entertainment industry, we call these four models the Orchestra model, the Creative Bazaar model, the Jam Central model, and the Mod Station model (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. The four models of network-centric innovation

We now paint a picture of the defining characteristics of each of these models, drawing parallels from the music and entertainment world. We will explore each model in greater detail in Chapters 5 through 8 of the book.

The Orchestra Model

When we think about an orchestra, we visualize a conductor holding sway with his wand, directing a group of musicians—each a specialist in a specific musical instrument. The musicians come together to play scripted (often, classical) music. The scripted music—whether it is Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony or Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G Minor—provides a well-defined structure for the performances of individual musicians. Although individual musicians might have some leeway in interpreting the music creatively, they are generally supposed to follow the script. And to a large extent, the responsibility of coordinating the musicians falls with the conductor. The conductor communicates with individual musicians (usually through gestures), and this communication determines whether the music that the audience hears is just a mechanical rendition of the script or a moving and elegant interpretation of the script. As the critic Eduard Hanslick noted in the 1880s, the best conductors are able to control and shape “every note and inflection emanating from the musicians under their command.”12

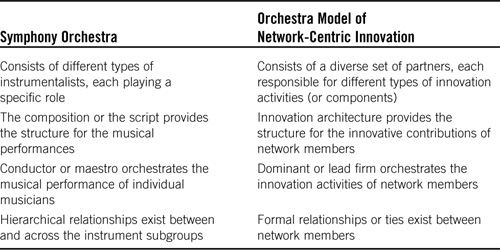

The Orchestra model for network-centric innovation closely resembles the organization and the structure of a typical symphony orchestra (see Table 3.1). In this context, the structure of the innovation space is fairly well-defined and the network leadership is centralized with a single dominant firm. The innovation context provides a clear basis for structuring the activities of the individual actors in the innovation network. And just as the musical instruments in an orchestra need to resonate with each other, the innovative contributions of network members in the Orchestra model also complement one another.

Table 3.1. The Orchestra Model of Network-Centric Innovation

Just as an orchestra is led by a conductor who orchestrates the musical performances of individual musicians to create a coherent symphony, in the network-centric innovation context, the leadership provided by the dominant firm is crucial to ensuring that the innovative contributions of individual contributors add up to a valuable whole.

Further, in an orchestra, often there is a hierarchy of leadership or a set of generally accepted (formal) relationships or ties between the instrumentalists. For example, each instrumental group or section has an assigned leader (principal or soloist) who is responsible for leading that group. Often, there is also a hierarchy between the instrument groups. For example, the violins are divided into two groups, first violins and second violins. The leader of the first violin group is considered the leader of the entire string section. Moreover, this leader is also the second-in-command of the orchestra, and is responsible for conducting the orchestra if the maestro is not present. Similarly, the principal trombone is considered the leader of the low-brass (trombone, tuba, and so on) section, whereas the principal trumpet is generally considered the leader of the entire brass section.13 Even though such a set of hierarchical relationships might not translate directly into the network-centric innovation context, the analogy lies in the formal relationships or ties among the members of the innovation network.

The Orchestra model of network-centric innovation describes a situation wherein a group of firms come together to exploit a market opportunity based on an explicit innovation architecture that is defined and shaped by a dominant firm. The innovation architecture typically emphasizes efficiency over novelty, so there is a heavy emphasis on modularity of the innovation architecture. Innovation processes tend to be highly organized and coordinated with significant investments made in infrastructure to support the roles and activities of the members of the network.

Examples of the Orchestra Model range from Microsoft .NET initiative and Salesforce.com’s AppExchange network to Boeing’s development of the Dreamliner 787. These examples represent several variations of the Orchestra model. In Chapter 5, “The Orchestra Model,” we will examine the Orchestra model and these variations in more detail through specific examples.

The Creative Bazaar Model

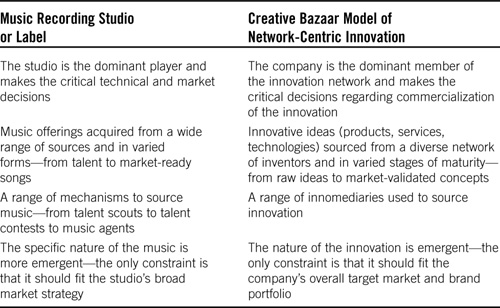

When you listen to your favorite new music artist, have you wondered how he or she got noticed from among the crowd of struggling artists, and ended up launching an album with a major record label? Record labels look for “diamonds in the rough” in lots of ways. They might look for promising but unknown artists through talent scouts and talent contests like the American Idol. Or they might opt for tried and trusted performers who have a new album or single and who have a ready-made audience. In both situations, the record company typically only specifies the broad category of interest—the genre of music and the target customer segments—and not the lyrics or choreography of the music. However, the label does have the final say in selecting, developing, and marketing the albums. In other words, while the record label still plays the role of a dominant player, it takes a flexible and open approach to finding talent and letting them come up with innovative music. In effect, the record label shops around in the talent bazaar.

This model of music production is what we think of as an analogy in proposing the second model of network-centric innovation—the Creative Bazaar model (see Table 3.2). This model describes a context wherein a dominant firm shops for innovation in a global bazaar of new ideas, products, and technologies and uses its proprietary commercialization infrastructure to build on the ideas and make them “market-ready.” The commercialization infrastructure might include design capabilities, brands, capital, and access to distribution channels.

Table 3.2. The Creative Bazaar Model of Network-Centric Innovation

In much the same way as a music studio sources new musical compositions from a wide variety of artists, companies that use the Creative Bazaar model to source new product/service use lots of mechanisms to source new ideas and technologies from inventors. For example, product scouts and licensing agents identify promising new product and technology ideas and bring them to large companies for further development and commercialization. Companies can also shop for more market-ready products (that is, product or technology concepts that have been prototyped and market validated) and acquire them from incubators and venture capital firms. Regardless of the sourcing approach, the company plays the dominant role in the innovation network by offering its infrastructure for developing and commercializing the innovation. However, the nature of the innovation space is not that well-defined, because the target markets or technology arenas are defined relatively broadly, and it isn’t clear where the idea will come from, or what it will look like.

In summary, the Creative Bazaar model aims to seek out and bring to fruition innovation opportunities that meet the broad market and innovation agenda of the dominant firm. The term bazaar implies a dizzying array of wares on offer, ranging from raw ideas and patents to relatively mature or “market-ready” new product concepts, as well as the presence of different hawkers that companies can deal with, from idea scouts, patent brokers, and electronic innovation marketplaces to incubation agencies, venture capitalists, and so on.

The Jam Central Model

Consider a musical jam session. It typically involves a group of musicians getting together to play or “jam” without extensive preparation and without the intention to follow any specific musical pattern or arrangement. Improvisation is the key to a good jam session. Musicians often follow a “call and response” pattern—that is, a succession of two distinct notes or phrases played by different musicians, where “the second phrase is heard as a direct commentary on or response to the first.”14

The term jam can be traced back to 1929 when it was used to refer to “short, free improvised passage performed by the whole band.”15 The term signifies two key themes: It is a group activity and it is improvisational. The degree of improvisation might vary from being loosely based on an agreed chord progression to being completely improvisational. Further, unlike an orchestra or other musical contexts, typically, there is no single leader in a jam session. All the musicians share in the responsibility to keep the time or the rhythm.

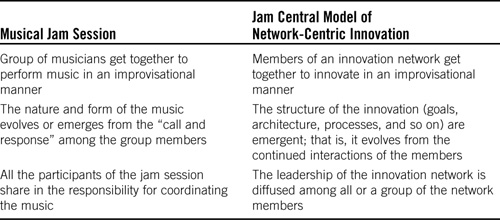

The jam session is our inspiration for the third model of network-centric innovation—the Jam Central model (see Table 3.3). This model involves individual contributors coming together to collaborate in envisioning and developing an innovation. The innovation space is typically not well structured and the objectives and direction of the innovation tends to emerge organically from the collaboration. There are no dominant members, and the responsibility for leading and coordinating the activity is diffused among the network members. Even if the leadership is not equally shared by all members, key decisions that shape the innovation processes and outcomes tend to evolve from the interactions of the network members.

Table 3.3. The Jam Central Model of Network-Centric Innovation

In sum, the Jam Central model is characterized by a shared exploration of an innovation arena by a peer group of contributors who share in the responsibility of directing and coordinating the innovation effort.

The Mod Station Model

The term mod originally stood for modernism and was used to refer to a youth lifestyle based around fashion and music that developed in London, England, in the late 1950s.16 But the term had a rebirth in the computer gaming industry in the early 2000s. Computer-based games that were modifications of existing games were referred to as “mods.” In other words, mod stood for modification. And, this is the perspective that we adopt here when using the term mod.

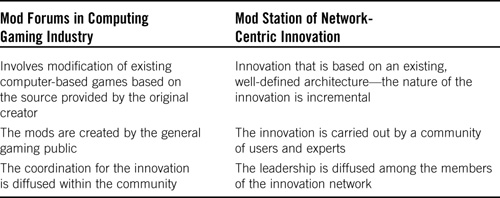

By offering the source of a video game to a community of gamers, a company can enable the creation of variations of the game. These modifications can involve adding new characters, new textures, new story lines, and so on. Depending on the extent of modifications, they can be “partial conversions” or “total conversions.” Total conversions typically turn out to be completely new games that happen to use some of the basic content or structure of the original game. Mods are made by the general gaming public or modders. Increasingly, the gaming companies have started assisting modders by providing extensive tools and documentation. The mods are then distributed and used over the Internet. The most popular mod is Counter-Strike, a game that originated as a modification of another game called Half-Life produced by Valve Corporation, a software firm based in Bellevue, Washington.

Based on the mod idea, we define the fourth and final model for network-centric innovation—the Mod Station model (see Table 3.4). This model has two key characteristics. First, it largely involves modifying or leveraging an existing (product, process, or service) innovation—that is, activities that occur within the boundaries of a predefined innovation space, and aim to add, enhance, or adapt existing products or services. Second, it occurs in a community where the norms and values that govern the innovation are established by the community and not by any one dominant firm.

Table 3.4. The Mod Station Model of Network-Centric Innovation

In sum, the Mod Station model is focused on exploiting existing innovation or knowledge to address market/technological issues by a community of innovators (innovation users, customers, scientists, experts, and so on). Examples of such network-centric innovation range from commercial open source communities such as SugarCRM to open source projects such as OpenSPARC wherein networks of scientists and experts innovate within the boundaries defined by an existing product or process architecture.

From the Plays to the Players

These four models help us to structure the landscape of network-centric innovation. But our framework is not yet complete. In each of the models of network-centric innovation, firms can play different types of roles. What is an innovation role? And, what are the broad categories of such innovation roles? Further, all innovation networks require some basic operational infrastructure for creating as well as capturing value. This includes the mechanisms for managing intellectual property rights and the systems for sharing knowledge. What are the general elements of the network operational infrastructure? In the next chapter, we address these questions.