1.4. The Piccadilly Organization

Piccadilly People

In this part of the Project, we ask you to build a current physical model of the Piccadilly organization. This is to give you more background on how the company currently operates. Your future system may well improve on the current state of affairs, but first you need to understand what it is that you seek to change.

The following is a description of how the Piccadilly departments are currently organized. After you have read it, you will build a current physical model of this company. Your Project will affect these departments, so let’s tour them all and find out what each of them does.

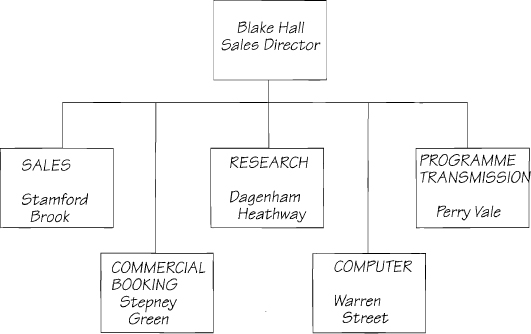

Figure 1.4.1: An organization chart showing the Piccadilly directors and high-level managers. Including all clerical and secretarial staff, Piccadilly employs approximately two hundred people.

Sales Department

Stamford Brook is the ambitious young manager of the Sales Department. Stamford would be the best-dressed member of the Piccadilly staff if he didn’t wear such outlandish socks. Hosiery considerations aside, he is an excellent manager, and usually meets his sales targets.

Figure 1.4.2: Stamford Brook, the manager of the Sales Department. Stamford is an excellent manager and is well-respected by his staff.

Stamford is responsible for making sure that the airtime is sold at a rate that will meet the sales target. Every morning, Stamford gets the airtime analysis from the Commercial Booking Department. He uses this analysis when he meets with his thirty sales executives and reviews their progress against the quarterly sales target instructions set by Blake Hall, the sales director. Blake calculates the target based on the amount of money that he estimates will be spent on television advertising during the quarter.

Under Stamford’s direction, the sales executives sell airtime to the advertising agencies. Some of the sales work is done on the telephone, and sometimes the executives meet their agency contacts face to face. This is a business in which personal contacts mean a lot. If you have lunch at Le Pied de Cochon, the small bistro facing onto Victoria Square, you will always find at least one of the sales executives entertaining a buyer from an agency. Meanwhile, in the public bar of the Royal facing onto Victoria Square, you will always find at least one of the sales executives entertaining a buyer from an agency. Meanwhile, in the public bar of the Royal Oak, other executives are pushing the advantages of buying Piccadilly airtime to their agency contacts.

Let’s review how airtime is sold. It all starts when the advertising agency informs the sales executive of the requirements for a new advertising campaign. The executive looks for advertising time on the breakchart where all the bookings and available time are recorded. The executive uses availability from the breakchart, together with the ratecard and the programme transmission schedule, to plan a campaign for the product. Naturally, the executive selects some higher-priced spots to help meet the sales target. When suitable spots have been selected, the executive sends his suggestions for the campaign to the agency.

Selecting spots for a campaign is a complex business and requires a great deal of experience. Later, you will talk to some of the sales executives to analyze their part of the business in more detail.

The agency reviews the suggested campaign, and tells the executive which spots the agency wants. Each spot has a number so that it can be uniquely identified. The executive finalizes the deal by sending the agency an agreed campaign document and, at the same time, tells the Commercial Booking Department people about the deal. They keep the breakchart up to date by recording the spots the executive has sold.

People from the Commercial Booking Department tell the sales executives if one of their spots has been preempted, or is likely to be. Whenever there is the likelihood of a spot being preempted, the executive warns the agency and recommends a higher rate that would protect the spot. Usually the agency agrees to upgrade the spot, and the executive confirms the upgrade with both the agency and the Commercial Booking Department.

Each advertising agency is assigned to one executive so that he can build a solid working relationship with the contact at the agency. This sort of service is vital in a business that relies so much on personal interaction. Whenever Piccadilly employs a new executive, the Personnel Department sends his qualifications to Sales so that a plan can be made for assigning agency responsibilities. Agencies are accredited, which means that they are obligated to pay for the airtime they buy. When a new agency presents its credentials to Piccadilly, the Sales Department sends a new agency form to the Computer Department so that the all-important computer records are kept up to date.

Commercial Booking Department

The manager of the Commercial Booking Department, Stepney Green, is admired for her ability to remain calm in the midst of frantic activity. Between 9 and 5, her department is very busy indeed. Sales executives rush in and out to find availability on the breakchart and to leave word of the airtime that they have sold. The spot administrators, who maintain the breakchart, have to move quickly to keep up with the rapid changes, particularly when transmission time nears. Overlaying all this activity is the almost constant ringing of the telephones.

The Commercial Booking Department first learns about the commercial breaks between programmes from the quarterly programme transmission schedule. When a new schedule is received, one of the spot administrators writes each break onto a form called a breaksheet. The breaksheets exist because selling activity on these breaks can be fairly slow until closer to transmission date, and there is not enough room to fit them onto the hanging breakchart files. A month before transmission date, the number of sales, moves, and upgrades increases greatly. To make the breaks more accessible to the spot administrators, the administrators transfer the breaksheet information to one of the hanging files on the breakchart. A copy of the programming rules set by the Broadcasting Board is pinned to the breakchart so that the spot administrators know the current restrictions on spot placements.

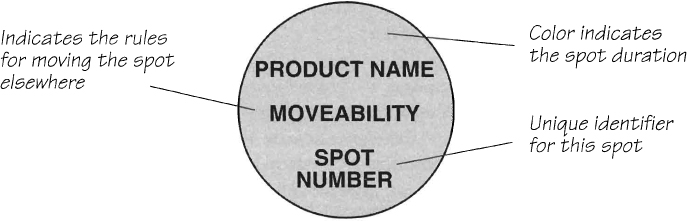

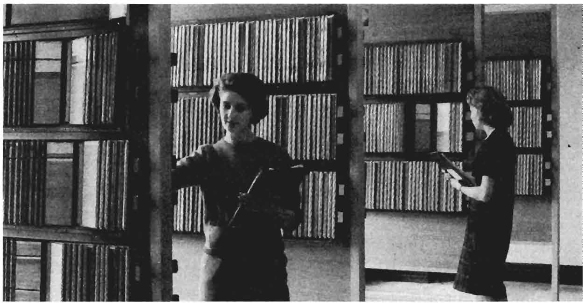

Figure 1.4.4: Piccadilly Television’s breakchart, which consists of banks of hanging files. Each file can lie flat and show the pattern of the commercial breaks for a day. Each day has a certain number of advertising breaks, each of which contains a number of spots. When spots are sold, colored stickers are attached to the breakchart.

The job of the spot administrators is to record the sales of commercial airtime. They use stickers showing the duration, product name, moveability code, and unique number to record the spots on the breakchart. To make space for a new spot, the spot administrator often has to move one or more existing spots. A spot can be sold for a variety of different rates, and each rate has its own moveability rules. For instance, a spot sold at the lowest rate, known as run-of-week, is governed by moveability rules that allow it to be placed anywhere on the breakchart within a given week, whereas a spot sold at a middle rate, known as run-of-day, has its moveability restricted to any commercial break within a time segment on a specified day. Paying the highest rate, fixed, for a spot means that it cannot be moved from the break in which it was originally sold.

When a sales executive confirms a sale, the administrator has to find a commercial break that conforms to the rate charged for the spot and satisfies the programming rules. This is called “slotting a spot.” Whenever necessary, the administrator makes room by displacing a spot sold at a lower rate. Now a home must be found for the displaced spot, which may in turn displace another. Slotting continues until suitable homes are found for all the spots. Sometimes, there is no room left on the breakchart. In that case, the lowest-priced spot in the chain is preempted and loses its place on the breakchart. As soon as a spot is preempted, the appropriate sales executive is told about it so that he can break the news to the agency.

After each day’s trading, the spot administrators analyze the breakchart. The analysis reveals any unsold airtime and any that has been sold at a rate considered too low for the commercial break. The sales manager uses this information to monitor the sales executives’ work.

On the evening of the day before transmission, the planned break transmission schedule is sent to the Programme Transmission Department in Nuffield-on-the-Moor. The transmission controllers in Nuffield use the schedule to identify the advertising in the commercial breaks.

Research Department

The main task for Dagenham Heathway and his twelve research assistants is to set the rates for the sale of airtime. The researchers are all mathematicians, and during their coffee breaks, they enjoy solving the tough puzzles or brainteasers that paper the walls of the department. The work of setting the rates is another tough mathematical puzzle. The rates have to be low enough to allow the sales executives to be competitive, and high enough to meet the sales target set by management.

Figure 1.4.6: Dagenham Heathway has responsibility for setting the rates for the sale of commercial airtime

The sales target instructions come from management at the beginning of every quarter. The Research Department then calculates the new rates based on these instructions. However, the new rates are not just plucked out of the air. Television ratings reports supplied by the audience measurement bureaus provide information on who watches which programmes. The researchers use the ratings to identify the likely audience for each time period, or segment as they call it, in a day. The agencies want to buy into the segments with the biggest potential audience, and the researchers set a higher price for the spots making up the commercial breaks in these segments.

The price for advertising reflects the spot’s duration, moveability, and segment. The objective is to set rates such that if all the spots are sold at the price that the researchers anticipate, the sales target will be met.

After they have calculated the rates, the researchers publish a ratecard that is sent each quarter with the sales target instructions to the Sales Department. The ratecard is also sent to the Computer and Commercial Booking departments, as well as to all of the advertising agencies.

The ratecard specifies the price and the moveability of advertising spots. As you learned from reading about the Commercial Booking Department, a low rate means that a spot can be moved to a wide variety of places on the breakchart, whereas a higher rate guarantees that a spot is transmitted within a much narrower window of time. A spot bought at the highest rate has a guaranteed transmission within a specific commercial break.

Computer Department

Warren Street is the Computer Department manager. His staff of analysts and programmers are fully occupied maintaining the ten-year-old computer system. Along with revenue reports for Piccadilly management, the system produces invoices for the agencies. The invoices show the exact details for the spots that have been transmitted, and are generated from the transmission times sent from the Programme Transmission Department.

The users would like the computer to give them more facilities, but it just isn’t possible given the current circumstances. Programming is done in an outmoded, low-level language so that the simplest modification takes weeks; the department’s Tardis 2 computer is already stretched to the limit.

Programme Transmission Department

Perry Vale runs the Programme Transmission Department in Nuffield-on-the-Moor. Perry’s main task is to produce the quarterly programme transmission schedule. Here’s how it’s done: Programme suppliers from all over the world offer Piccadilly new programmes. Whenever Perry thinks that a programme will suit Piccadilly’s requirements, he sends a programme purchase agreement to the supplier.

Now, Perry has to decide when the programme will be transmitted. He has to show it at a time of day that will attract the maximum audience for that kind of programme. To consider the competition for the audience at that time, he gets copies of the opposition’s schedules to keep him current on which programmes the opposition’s channels are planning to show. Although Piccadilly is the only commercial channel in the Midlands, there are two noncommerciel channels run by the British Broadcasting Corporation and funded by television viewer license fees and government subsidies. These channels, BBC1 and BBC2, are well-known for the high quality of their programmes and provide Piccadilly with serious competition.

Figure 1.4.7: The quarterly programme transmission schedule is set by Perry Vale, the department’s director in Nuffield-on-the-Moor.

Perry must also keep the Broadcasting Board happy by presenting a balanced schedule. The Board will not approve a schedule dominated by game shows, soap operas, and football, but likes to see a mix of programmes that both educate and entertain. The Board’s rules even specify the percentage of different types of programmes that must be shown during a three-month period. The point is to provide the public with what the Board considers to be varied and entertaining television viewing.

When Perry decides where he would like to place the new programmes, he sends his preliminary schedule to the Research Department. The researchers predict the rating for each programme in its proposed time slot. If Perry decides that the predicted rating is satisfactory, he adds the programme to the programming plan. This plan, which is in the form of a giant chart on the wall of the scheduling room, displays the schedule for the coming six months.

Every quarter, finalized programme transmission schedules are sent to the Sales, Commercial Booking, and Research departments, as well as to the Broadcasting Board for its review. The version of the schedule that Perry sends to all of the agencies highlights the new high-rating programmes in the hope that it will encourage them to book their spots early.

Perry’s department also is responsible for the commercial copy, which is recorded on a type of videocassette. These automatic cassette recordings (ACRs) are sent to Nuffield-on-the-Moor by the film production company. The Piccadilly copy librarians store the ACRs in the library near the transmission room.

When the break transmission schedule arrives from London, the copy librarians know which products will occupy which commercial breaks. The copy library typically holds several different ACRs for the same product, so the agency must send copy transmission instructions to specify when each cassette should be used. The librarians refer to the transmission schedule and the copy transmission instructions when they load the ACRs on the trolleys ready for the transmission room.

It would be dangerous to keep outdated copy in the library, as it might be transmitted by mistake. When the agency decides that an ACR is outdated, it sends disposal instructions. The library staff destroys the recording and updates the copy register. At the end of each day’s transmission, the actual transmission times for each spot are sent to the Computer Department in London.

Your Strategy

So far, you’ve built a first-cut context diagram and a data model for Piccadilly. These give you a fairly precise idea of the scope of the Project. However, they cannot yet be considered perfect.

You have just read a more detailed account of how Piccadilly Television currently does business. We now ask you to draw a data flow diagram of the organization to reflect your new level of knowledge. Is it appropriate to build such a model at this stage of the Project? There are several factors that indicate this data flow model is relevant:

1. Because you are now operating at a more detailed level, you will probably find some discrepancies between your context diagram and your new model. Don’t worry. This happens in all projects, and you simply bring the context up to date by correcting the balancing between your new model and the context diagram.

2. The context must be verified. When you model the organization as a whole, it gives you the chance to see how much of it can be changed by a new system. If everything that you model can be changed, your original context is not large enough. Keep in mind that the context of analysis is always larger than the extent of any new system.

3. Since you’re probably not familiar with this business, it makes sense to spend some more time modeling the current physical view of the system. You need to become acquainted with the users and to build a working relationship with them. This data flow model, and other models like it, give your users a chance to become familiar with your analysis style.

4. If Piccadilly management is asking for a new system, the current one most likely has some problems. An organization-wide model helps to highlight the problems and possibly to suggest corrective action.

This data flow model will be your biggest yet in this book. Be prepared: It will take longer than the Textbook exercises. You will also find that there is too much information here in this chapter, and you’ll need to summarize it in a meaningful way. The lessons from Chapter 2.7 Leveled Data Flow Diagrams should be useful, particularly the guideline about how much information you can reasonably have on one page.

The partitioning of this model should be understandable to upper management, which is appropriate when you are modeling almost all of the organization. Later, you will interview some of the people working in the departments and build more detailed models of their operations.

You will probably discover new entities and relationships. If you do, update the data model you built in Chapter 1.3 What About the Business Data?

Finally, as you build the model, keep a list of any questions that you’d like to ask the users. (Of course, since you can’t ask the fictional users, we’ll try to anticipate your questions.) As always, there will be fragments of the business policy that the text doesn’t make completely clear. You analyze systems—you don’t invent policy, nor do you guess it. When something is unclear, the best action is to draw what you think is the correct answer, and highlight it with a large question mark. We’ll discuss possible questions when we examine the sample answer in Chapter 3.3.