1.6. Selling the Airtime

Your Strategy

It is still early in the Piccadilly Project. As yet, you probably don’t have a detailed enough picture of the business to go on to the next stage. Consequently, we suggest that you build more of the current physical viewpoint. This chapter gives you some more detailed information about the way Piccadilly Television sells commercial airtime. Use the information in this chapter to produce a data flow diagram that is a lower level or child of the diagram you produced in Chapter 1.4 The Piccadilly Organization.

You may notice some repetition and even some contradiction between the information in this chapter and the information you received earlier. This is normal in any project where you get information from a number of different sources. You, the analyst, should make your most reasonable interpretation, and mark it as a question to be raised with the users.

This next option is directed to followers of the ![]() More Difficult and

More Difficult and ![]() Most Difficult Trails. If you feel that building more of the current physical viewpoint is unnecessary, and if you already have a good idea of where you want the analysis to take you, go directly to Chapter 1.7 Strategy: Focusing on the Essentials. You can save some time by not building a physical model. However, there is the risk you’ll misunderstand the current system. You can simulate the risk right now: There is a complete current physical model in Chapter 3.6. Try to complete the Project while minimizing your references to the current physical model. Whenever you find yourself needing to refer to it, return to this chapter and build just the fragment of the model that you really need, and check it against the one there. This approach will give you some experience with the strategy of physical modeling on demand.

Most Difficult Trails. If you feel that building more of the current physical viewpoint is unnecessary, and if you already have a good idea of where you want the analysis to take you, go directly to Chapter 1.7 Strategy: Focusing on the Essentials. You can save some time by not building a physical model. However, there is the risk you’ll misunderstand the current system. You can simulate the risk right now: There is a complete current physical model in Chapter 3.6. Try to complete the Project while minimizing your references to the current physical model. Whenever you find yourself needing to refer to it, return to this chapter and build just the fragment of the model that you really need, and check it against the one there. This approach will give you some experience with the strategy of physical modeling on demand.

If you are new to systems analysis or if you have chosen to give yourself maximum practice by following the ![]() Easiest Trail, then press on with the current physical model.

Easiest Trail, then press on with the current physical model.

Interview with Stamford Brook, Sales Manager

Read this statement by Stamford Brook. Then, build a model of the Sales Department.

“The easiest way for you to understand how this business works is for me to give you an example of how we sell our airtime. The director I report to is Blake Hall. At the start of each quarter, Blake gives me a sales target that he and the Board of Directors have agreed to. The target tells me how much revenue I have to generate by selling airtime during the coming three months.

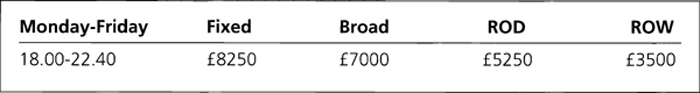

“I use the sales target to set the sales policy. Let me explain that. First, I know you’ve already had a look at our ratecard, so you know there are several possible rates for each commercial break.

I know how much money we need to bill, so I figure out which of the rates will be the minimum for each break. I know that some breaks will be very popular. For instance, we could sell any break during a first-run movie many times over. It’s silly to sell this time at ROD or ROW rates; it only results in preemptions later on. Instead, I set the breaks in a first-run movie at fixed or broad. Why don’t I set all breaks at fixed and maximize the revenue? Because there are limits on how much advertisers will spend in a quarter. The sales target is a realistic estimate of Piccadilly’s share of the total spend. Also, no advertiser will pay fixed rates for the commercial break at the end of the broadcast day when anybody in front of a television set is asleep. That’s how I set my sales policy: by putting a recommended minimum rate against each commercial break.

“Every morning, I get an airtime analysis report from the Commercial Booking Department. This report tells me the rates and revenue for all the time that has been sold that week. The report helps me to keep track of our progress toward the sales target. Sometimes, depending on the demand for time, I adjust the minimum rates on the breaks.

“Our clients are the advertising agencies, which are hired by companies that want to run advertising campaigns for their products. When an agency tells us about a campaign, they quote the campaign budget and the budget amount that they intend to spend with Piccadilly. The campaign budget is not all spent with Piccadilly—it’s a national budget that is shared among a number of regional television companies. Our aim is to persuade the agencies to spend more of their budget with us. We try to get a larger share by convincing the agencies that they will get better value for their money if they spend it with us.

“For instance, yesterday one of the agencies phoned with campaign requirements for a new type of liqueur chocolate bar. They told Dollis Hill, the sales executive, that of the £1,000,000 in their total budget, they intend to spend £250,000 with Piccadilly. The remainder will be spent with the other television companies.

“The campaign will run from December to the end of February. (I suppose the cold weather is likely to make people feel more like eating sweets.) As the chocolate is filled with alcohol, the target audience is adults. The agency also told us how many television rating points they want us to achieve. Their commercials will all be thirty seconds long. Dollis recorded the requirements in her campaign file, and then spent the morning planning the campaign.

“First, Dollis considered the spots that would be suitable for the campaign. She checked the breakchart for what times were available, and she looked up the predicted ratings stored in the programme schedules file to see which programmes are most watched by adults. She priced the time using my sales policy minimum rates for the breaks and the prices on the ratecard.

“Finally, she matched the priced time against the campaign requirements. She selected a mixture of spots that satisfied the requirements. In other words, the spots she chose would deliver the required audience, and the total came to a little over the agency’s budget. (We always try to get a little more than our share.) Dollis recorded her choices in the campaign file and then phoned the agency with her suggestions for the campaign. Planning these campaigns takes a lot of time; we hope the new system will give us some computerized help.

“The agency phoned back in the afternoon and told Dollis which spots from her suggested campaign they wanted. She sent a notice to the agency that signified our agreement to the deal. She also sent a copy to the Commercial Booking Department so that they could record the selected spots on the breakchart. Dollis keeps details of the campaign in her file, so that she can find them quickly.

“The spots in the chocolate campaign have not been bought at the highest rate. However, we do book them into a designated break on the breakchart. If someone else pays more for that time, the spots can be moved or, in some cases, preempted. If the Commercial Booking people tell us about a likely spot preemption, we phone the agency and give them a preemption warning. We tell them the rate they would have to pay to upgrade the spot. Usually the agency responds by asking us to upgrade the rate for the spot. Then we have to confirm the upgrade and give the Commercial Booking people a copy.

“Sometimes, we hear that a spot has already been preempted. In this case, we find a suitable replacement break, usually at a higher rate, for the preempted spot and tell the agency of this choice. In the rare cases when the agency does not want to pay the extra for the new spot, they send us a spot cancellation. When a spot is canceled, we update our campaign file and advise the Commercial Booking people.

“Selling airtime is a challenging job. The sales executives enjoy it, and tend to stay here for a long time. Occasionally we have to hire someone new. When that happens, Personnel sends us the details of the new recruit and we record them in the Sales Executive Register. We also have to assign agencies to the new executive. This business relies on personal dealings, and we have to be sure that we match the right person to the account.

“When a new agency becomes accredited, the agency advises us. We have to assign the new agency to an executive and record the name, address, phone number, and person to contact in the Agency Register. We also have to fill out a new agency form and send it to the Computer Department. They need it for billing.

“Well, I think that’s it, except for the files over there. That’s where we keep the ratecards and the programme schedules file. This file holds the programme transmission schedule and predicted ratings.

“I hope this gives you what you need to get started. I’ll see you tomorrow after you’ve had a chance to think about all this. You’re sure to have some questions for me, and you may want to talk to some of the sales executives. Or maybe you’ll want to watch how they do their work.”

Hints on How to Work

Stamford Brook has described how Piccadilly sells its airtime. Now you have to make sure that what you heard (or read) is what Stamford meant to tell you. The best way to do this is to build a data flow model of the Sales Department and show it to Stamford.

The model that you produce here has to balance with its parent: bubble 3 from Diagram 0 in Chapter 3.3 (Figure 3.3.1). You can start by drawing all the flows that enter or leave the parent, and then connect them to the processes that Stamford described.

As you work through Stamford’s statement, try to identify each data flow mentioned and each identifiable process. You will find that most of the paragraphs yield some data items and/or some processes. Draw each item as you come to it. Don’t worry for the moment if you have many pieces that do not appear to be connected. By the time you finish the interview, there should be enough hanging data flows to connect everything. If your model turns out to have too many bubbles, group some of the processes and level upward to make a better partitioning.

Think of the data flow model as a note-taking device. As the users talk to you, draw what is being said. Remember that neatness beyond legibility is not important. You are trying to record what is being said. If your model doesn’t make sense, then perhaps what you were told doesn’t either. As soon as a user stops speaking, turn the model around and talk your way through it. This usually helps each user to clarify and re-explain the system.

Alternatively, you may prefer to start by making an assumption about a group of processes, and then leveling down to show the details. For example, Stamford gave you information about Dollis Hill and her advertising agency’s campaign. You could add a process called PLAN A CAMPAIGN or something similar to your model, draw all its inputs and outputs, and return to it later using a lower-level diagram to show its details.

Sometimes, it’s useful to annotate your data flow diagrams with comments enclosed in asterisks, like so: * Comment *. The typical sorts of comments concern

• the person who is carrying out a process

• the location where a process is being done

• the name of a form that is carrying information

• the color of a report (if it adds to the understanding of the model)

• the name of a file (if it is different from the name in your model)

• anything else that helps you to communicate with your users

It is unlikely that your users will ever present information in neatly partitioned paragraphs, as you have in this book, but you can overcome this handicap by asking them questions. What questions to ask? Follow the data. You have the data flows that enter or leave this area of the business. (Get them from the parent diagram.) Ask the users what happens to each of these flows: “How do you use them? What do you do to produce them?” As the users describe each process and its related data flows, ask enough questions so that you know what happens to every one of the flows. Use the model to identify the areas where you need to ask more questions.