32. Protecting Your Data from Loss and Theft

Preparing for Trouble

Computer problems, like the proverbial death and taxes, seem to be one of those constants in life. Whether it’s a hard disk giving up the ghost, a power failure that trashes your files, or a virus that invades your system, the issue isn’t whether something will go wrong, but rather when it will happen. Instead of waiting to deal with these difficulties after they’ve occurred (what we call pound-of-cure mode), you need to become proactive and perform maintenance on your system in advance (ounce-of-prevention mode). This not only reduces the chances that something will go wrong, but also sets up your system to recover more easily from any problems that do occur.

A big part of ounce-of-prevention mode is the unwavering belief that someday something will go wrong with your computer. That might sound unduly pessimistic, but hey, this is a PC we’re talking about here, and it’s never a question of if the thing will go belly up one day, but rather when that day will come.

With that gloomy mindset, the only sensible thing to do is prepare for that dire day so that you’re ready to get your system back on its feet. So, part of your Windows 10 maintenance chores should be getting a few things ready that will serve you well on the day your PC decides to go haywire on you. Besides performing a system image backup (which we describe a bit later), you should be setting system restore points and creating a system recovery disc. The next two sections cover these last two techniques.

Backing Up File Versions with File History

High-end databases have long supported the idea of the transaction, a collection of data modifications—inserts, deletions, updates, and so on—treated as a unit, meaning that either all the modifications occur or not one of them does. For example, consider a finance database system that needs to perform a single chore: transfer a specified amount of money from one account to another. This involves two discrete steps (I’m simplifying here): debit one account by the specified amount and credit the other account for the same amount. If the database system did not treat these two steps as a single transaction, you could run into problems. For example, if the system successfully debited the first account but for some reason was unable to credit the second account, the system would be left in an unbalanced state. By treating the two steps as a single transaction, the system does not commit any changes unless both steps occur successfully. If the credit to the second account fails, the transaction is rolled back to the beginning, meaning that the debit to the first account is reversed and the system reverts to a stable state.

What does all this have to do with the Windows 10 file system? It’s actually directly related because Windows 10 includes an interesting technology called Transactional NTFS, or TxF, for short. (New Technology File System [NTFS] is the default Windows 10 file system.) TxF applies the same transactional database ideas to the file system. Put simply, with TxF, if some mishap occurs to your data—it could be a system crash, a program crash, an overwrite of an important file, or even just imprudent edits to a file—Windows 10 enables you to roll back the file to a previous version. It’s kind of like System Restore, except that it works not for the entire system, but for individual files and folders.

Windows 10’s capability to restore previous versions of files and folders comes from two processes:

![]() Once an hour, Windows 10 creates a shadow copy of your user account files. A shadow copy is essentially a snapshot of the user account’s contents at a particular point in time.

Once an hour, Windows 10 creates a shadow copy of your user account files. A shadow copy is essentially a snapshot of the user account’s contents at a particular point in time.

![]() After creating the shadow copy, Windows 10 uses transactional NTFS to intercept all calls to the file system. Windows 10 maintains a meticulous log of those calls so that it knows exactly which files and folders in your user account have changed.

After creating the shadow copy, Windows 10 uses transactional NTFS to intercept all calls to the file system. Windows 10 maintains a meticulous log of those calls so that it knows exactly which files and folders in your user account have changed.

Together, these processes enable Windows 10 to store previous versions of files and folders, where a “previous” version is defined as a version of the object that changed after a shadow copy was created. For example, suppose that you make changes to a particular document each day. This means that you’ll end up with three previous versions of the document: today’s, yesterday’s, and the day before yesterday’s.

Taken together, these previous versions represent the document’s file history, and you can access and work with previous versions by activating the File History feature. When you turn on File History and specify an external drive to store the data, Windows 10 begins monitoring your libraries, your desktop, your contacts, and your Internet Explorer favorites. Once an hour, Windows 10 checks to see if any of this data has changed since the last check. If it has, Windows 10 saves copies of the changed files to the external drive.

Once you have some data saved, you can then use it to restore a previous version of a file, as described later in this chapter.

Selecting the File History Drive

To get started, connect an external drive to your PC. The drive should have enough capacity to hold your user account files, so an external hard drive is probably best. Now you need to set up the external drive for use with File History.

The easiest way to do this is to look for the notification that appears a few moments after you connect the drive. Click the notification, and then click Configure This Drive for Backup.

If you miss the notification, follow these steps instead:

1. In the taskbar’s Search box, type history and then click File History. The File History window appears.

2. Examine the Copy Files To setting. If you see your external hard drive listed, as shown in Figure 32.1, you can skip the rest of these steps.

3. Click Select Drive. The Change Drive window appears.

4. Select the drive you want to use and then click OK. Windows 10 displays the external drive in the File History window.

Using a Network Share as the File History Drive

What happens if you don’t have an external drive or if your drives don’t have enough capacity to store your user account files? For the latter, you can try excluding a folder or two from your file history, as we discuss in the next section. If that doesn’t work, you can still use File History if you have access (and permission to write file) to a network share. Follow these steps:

1. In the taskbar’s Search box, type history and then click File History. The File History window appears.

2. Click Select Drive to open the Select Drive window.

3. Click Add Network Location. Windows 10 opens the Select Folder dialog box and displays the Network folder.

4. Open the network computer you want to use, click the shared folder, and then click Select Folder. Windows 10 returns you to the Select Drive window and adds the network share to the drive list.

5. Make sure the network share is selected and then click OK. Windows 10 displays the share in the File History window, as shown in Figure 32.2.

Excluding a Folder from Your File History

By default, File History stores copies of everything in your Windows 10 libraries—including Documents, Music, Photos, and Videos—as well as your desktop items, contacts, and Internet Explorer favorites. However, in some situations you might not want every file to be included in your history. For example, if your external drive has a limited capacity, you might want to exclude extremely large files, such as recorded TV shows or ripped movies in your Videos library.

Similarly, you might have sensitive or private files in your Documents library that you do not want copied to the external drive because that drive can easily be stolen or lost. (A similar caveat applies to storing sensitive files on a shared network folder that other people might also be able to access.)

Whatever the reason, you can configure File History to exclude a particular folder from being copied to the external drive by following these steps:

1. In the taskbar’s Search box, type history and then click File History. The File History window appears.

2. Click Exclude Folders. The Exclude Folders window appears.

3. Click Add. Windows 10 displays the Select Folder dialog box.

4. Select the folder you want to exclude, and then click Select Folder. Windows 10 adds the folder to the Excluded Folders and Libraries list.

5. Repeat steps 3 and 4 to exclude any other folders you want to leave out of your file history.

6. Click Save Changes.

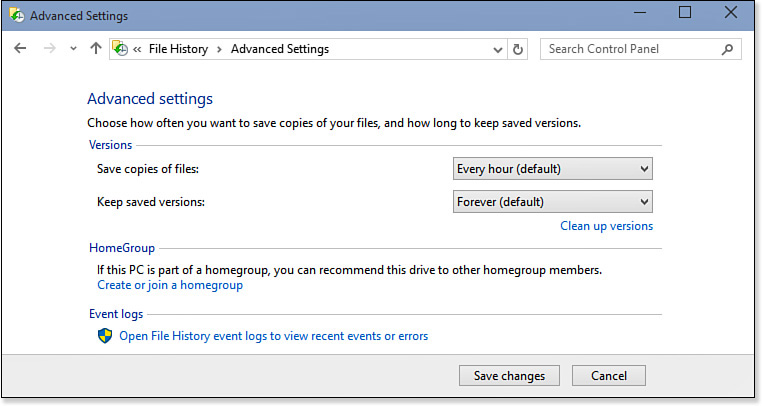

Configuring File History

File History uses the following default settings:

![]() File History looks for changed files every hour—If you are particularly busy, you might prefer a more frequent save interval to ensure you don’t lose any data. On the other hand, if you are running out of space on the external drive, you might prefer a less frequent save interval to preserve space.

File History looks for changed files every hour—If you are particularly busy, you might prefer a more frequent save interval to ensure you don’t lose any data. On the other hand, if you are running out of space on the external drive, you might prefer a less frequent save interval to preserve space.

![]() Tip

Tip

You don’t have to wait until the next scheduled backup. If File History is turned on (see “Activating File History”) and you have important changes you’d prefer to save right away, open File History and click Run Now.

![]() File History does not delete any of the file versions it saves—To free up space on the external drive, you can configure File History to delete versions after a specified time or when space is needed on the drive.

File History does not delete any of the file versions it saves—To free up space on the external drive, you can configure File History to delete versions after a specified time or when space is needed on the drive.

Follow these steps to configure these settings:

1. In the taskbar’s Search box, type history, and then click File History to open the File History window.

2. Click Advanced Settings to open the Advanced Settings window, shown in Figure 32.3.

3. Use the Save Copies of Files list to select a save frequency (from Every 10 Minutes to Daily).

4. Use the Keep Saved Versions list to select when you want File History to delete old versions of files (from 1 Month to 2 Years, Until Space is Needed, or Forever, which is the default).

5. If you’re using an external drive and your computer is part of a homegroup, you can check the Recommend This Drive box to allow other homegroup users the chance to use the same drive for their backups.

6. If you want to keep an eye on what File History is doing, click Open File History Event Logs to View Recent Events or Errors. This launches the Event Viewer and displays the File History Backup Log.

7. Click Save Changes to put the new settings into effect.

Activating File History

At long last, you’re ready to start using File History. In the File History window, click Turn On. If Windows 10 asks if you want to recommend the drive to your homegroup, click Yes or No, as you see fit. File History immediately goes to work saving the initial copies of your files to the external drive or network share.

![]() Note

Note

If you need to remove the external drive temporarily (for example, if you need to use the port for another device), you should turn off File History before disconnecting the external drive. In the taskbar’s Search box, type history and then click File History. In the File History window, click Turn Off.

Restoring a Previous Version of a File

When you click File History on your PC, as described earlier in this chapter, Windows 10 periodically—by default, once an hour—looks for files that have changed since the last check. If it finds a changed file, it takes a “snapshot” of that file and saves that version of the file to the external drive that you specified when you set up File History. This gives Windows 10 the capability to reverse the changes you have made to a file by reverting to an earlier state of the file. An earlier state of a file is called a previous version.

![]() Note

Note

Windows 10 also keeps track of previous versions of folders, which is useful if an entire folder becomes corrupted because of a system crash.

Why would you want to revert to a previous version of a file? One reason is that you might improperly edit the file by deleting or changing important data. In some cases, you might be able to restore that data by going back to a previous version of the file. Another reason is that the file might become corrupted if the program or Windows 10 crashes. You can get back a working version of the file by restoring a previous version.

Follow these steps to restore a previous version of a file:

1. In the taskbar’s Search box, type history and then click File History to open the File History window.

2. Click Restore Personal Files. The Home – File History window appears.

3. Double-click the library that contains the file you want to restore.

4. Open the folder that contains the file.

5. Click Previous Version (see Figure 32.4) or press Ctrl+Left arrow until you open the version of the folder you want to use. If you’d prefer a more recent version, click Next Version or press Ctrl+Right arrow.

Figure 32.4 Use the Home – File History window to choose which previous version you want to restore.

6. Click the file you want to restore.

7. Click Restore to Original Location (pointed out in Figure 32.4). If the original folder has a file with the same name, File History asks what you want to do.

![]() Replace the File in the Destination Folder—Click this option to overwrite the existing file with the previous version.

Replace the File in the Destination Folder—Click this option to overwrite the existing file with the previous version.

![]() Skip This File—Click this option to skip the restore and do nothing.

Skip This File—Click this option to skip the restore and do nothing.

![]() Compare Info for Both Files—Click this option to display the File Conflict dialog box (see Figure 32.5), which shows the original and the previous version side by side, along with the last modification date and time and the file size. Check the box beside the version you want to keep, and then click Continue. To keep both versions, check both boxes. File History restores the previous version with (2) appended to its filename.

Compare Info for Both Files—Click this option to display the File Conflict dialog box (see Figure 32.5), which shows the original and the previous version side by side, along with the last modification date and time and the file size. Check the box beside the version you want to keep, and then click Continue. To keep both versions, check both boxes. File History restores the previous version with (2) appended to its filename.

Figure 32.5 If the original folder has a file with the same name and you’re not sure which one to keep, use the File Conflict dialog box to decide.

Setting System Restore Points

One of the biggest causes of Windows instability in the past was the tendency of some newly installed programs simply to not get along with Windows. The problem could be an executable file that didn’t mesh with the Windows system or a Registry change that caused havoc on other programs or on Windows. Similarly, hardware installs often caused problems by adding faulty device drivers to the system or by corrupting the Registry.

To help guard against software or hardware installations that bring down the system, Windows 10 offers the System Restore feature. Its job is straightforward yet clever: to take periodic snapshots—called restore points or protection points—of your system, each of which includes the currently installed program files, Registry settings, and other crucial system data. The idea is that if a program or device installation causes problems on your system, you use System Restore to revert your system to the most recent restore point before the installation.

System Restore automatically creates restore points under the following conditions:

![]() Every week—This is called a system checkpoint, and it’s set once a week during the automatic maintenance window as long as your computer is running. If your computer isn’t running, the system checkpoint is created the next time you start your computer, assuming that it has been at least a week since that previous system checkpoint was set.

Every week—This is called a system checkpoint, and it’s set once a week during the automatic maintenance window as long as your computer is running. If your computer isn’t running, the system checkpoint is created the next time you start your computer, assuming that it has been at least a week since that previous system checkpoint was set.

![]() Before installing certain applications—Some applications (notably Windows Live Essentials and Microsoft Office) are aware of System Restore and will ask it to create a restore point prior to installation.

Before installing certain applications—Some applications (notably Windows Live Essentials and Microsoft Office) are aware of System Restore and will ask it to create a restore point prior to installation.

![]() Before installing a Windows Update patch—System Restore creates a restore point before you install a patch either by hand via the Windows Update site or via the Automatic Updates feature.

Before installing a Windows Update patch—System Restore creates a restore point before you install a patch either by hand via the Windows Update site or via the Automatic Updates feature.

![]() Before installing an unsigned device driver—Windows 10 warns you about installing unsigned drivers. If you choose to go ahead, the system creates a restore point before installing the driver.

Before installing an unsigned device driver—Windows 10 warns you about installing unsigned drivers. If you choose to go ahead, the system creates a restore point before installing the driver.

![]() Before reverting to a previous configuration using System Restore—Sometimes, reverting to an earlier configuration doesn’t fix the current problem or it creates its own set of problems. In these cases, System Restore creates a restore point before reverting so that you can undo the restoration.

Before reverting to a previous configuration using System Restore—Sometimes, reverting to an earlier configuration doesn’t fix the current problem or it creates its own set of problems. In these cases, System Restore creates a restore point before reverting so that you can undo the restoration.

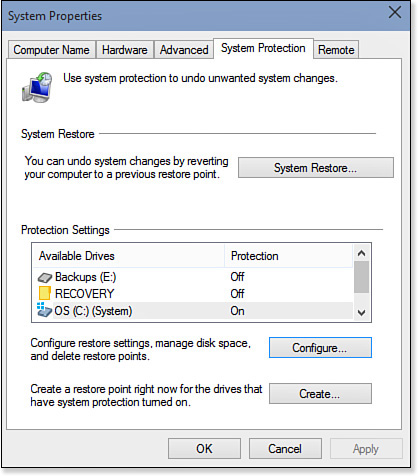

It’s also possible to create a restore point manually using the System Protection feature. Here are the steps to follow:

1. In the taskbar’s Search box, type restore and then click Create a Restore Point in the search results. This opens the System Properties dialog box with the System Protection tab displayed, as shown in Figure 32.6.

2. To create automatic restore points for a drive, click the drive in the Protection Settings list, click Configure, click the Turn on System Protection option, and then click OK.

3. Click Create to display the Create a Restore Point dialog box.

4. Type a description for the new restore point, and then click Create. System Protection creates the restore point and displays a dialog box to let you know the restore point was created successfully.

5. Click Close to return to the System Properties dialog box.

6. Click OK.

![]() To learn how to revert your PC to an earlier restore point, see “Recovering Using System Restore,” p. 624.

To learn how to revert your PC to an earlier restore point, see “Recovering Using System Restore,” p. 624.

Creating a Recovery Drive

We all hope our computers operate trouble-free over their lifetimes, but we know from bitter experience that this is rarely the case. Computers are incredibly complex systems, so it is almost inevitable that a PC will develop glitches. If your hard drive is still accessible, you can boot to Windows 10 and access the recovery tools, as we described in Chapter 26, “Troubleshooting and Repairing Problems.”

![]() To learn how to boot to the Windows 10 recovery tools, see “Accessing the Recovery Environment,” p. 614.

To learn how to boot to the Windows 10 recovery tools, see “Accessing the Recovery Environment,” p. 614.

If you can’t boot your PC, however, you must boot using some other drive. If you have your Windows 10 installation media, you can boot using that drive. If you don’t have the installation media, you can still recover if you’ve created a USB recovery drive. This is a USB flash drive that contains the Windows 10 recovery environment, which enables you to refresh or reset your PC, use System Restore, recover a system image, and more.

Before you can boot to a recovery drive, such as a USB flash drive, you need to create the drive. Follow these steps:

1. Insert the USB flash drive you want to use. Note that the drive must have a capacity of at least 512MB. Also, Windows 10 will erase all data on the drive, so make sure it doesn’t contain any files you want to keep.

The 512MB capacity applies only if you don’t also want to include your PC’s Recovery partition on the recovery drive. If you do want to include this partition (it’s a good idea), you’ll need a flash drive with enough capacity to hold the partition, which might be 15GB or more. (To check, use the taskbar’s Search box to type diskmgmt.msc, click Diskmgmt, and then use the Disk Management snap-in to view the size of the Recovery partition.)

2. In the taskbar’s Search box, type recovery and then click Create a Recovery Drive. User Account Control appears.

3. Click Yes or enter administrator credentials to continue. The Recovery Drive Wizard appears.

4. If you don’t want to add your PC’s Recovery partition to the recovery drive, click to uncheck the Copy the Recovery Partition from the PC to the Recovery Drive box. Click Next. The Recovery Drive Wizard prompts you to choose the USB flash drive, as shown in Figure 32.7.

5. Click the drive, if it isn’t selected already, and then click Next. The Recovery Drive Wizard warns you that all the data on the drive will be deleted.

6. Click Create. The wizard formats the drive and copies the recovery tools and data.

7. Click Finish.

To make sure your recovery drive works properly, you should test it by booting your PC to the drive. Insert the recovery drive and then restart your PC. How you boot to the drive depends on your system. Some PCs display a menu of boot devices, and you select the USB drive from that menu. In other cases, you see a message telling you to press a key.

Remove the drive, label it, and then put it someplace where you’ll be able to find it later, just in case.

Creating a System Image Backup

The worst-case scenario for PC problems is a system crash that renders your hard disk or system files unusable. Your only recourse in such a case is to start from scratch with either a reformatted hard disk or a new hard disk. This usually means that you have to reinstall Windows 10 and then reinstall and reconfigure all your applications. In other words, you’re looking at the better part of a day or, more likely, a few days, to recover your system. However, Windows 10 has a feature that takes most of the pain out of recovering your system. It’s called a system image backup, and it’s part of the system recovery options that we discussed in Chapter 26.

![]() To learn how to restore your PC from an image, see “Restoring a System Image,” p. 626.

To learn how to restore your PC from an image, see “Restoring a System Image,” p. 626.

The system image backup is actually a complete backup of your Windows 10 installation. It takes a long time to create a system image (at least several hours, depending on how much stuff you have), but it’s worthwhile for the peace of mind. Here are the steps to follow to create the system image:

1. In the taskbar’s Search box, type file history and then click File History. The File History window appears.

2. Click System Image Backup. The Create a System Image Wizard appears.

3. The wizard asks you to specify a backup destination. You have three choices, as shown in Figure 32.8. (Click Next when you’re ready to continue.)

![]() On a Hard Disk—Select this option if you want to use a disk drive on your computer. If you have multiple drives, use the list to select the one you want to use.

On a Hard Disk—Select this option if you want to use a disk drive on your computer. If you have multiple drives, use the list to select the one you want to use.

![]() On One or More DVDs—Select this option if you want to use DVDs to hold the backup. Depending on how much data your PC holds, you could be talking about using dozens of discs for this (at least!), so we don’t recommend this option.

On One or More DVDs—Select this option if you want to use DVDs to hold the backup. Depending on how much data your PC holds, you could be talking about using dozens of discs for this (at least!), so we don’t recommend this option.

![]() Caution

Caution

Many people make the mistake of creating the system image once and then ignoring it, forgetting that their systems aren’t set in stone. Over the coming days and weeks, you’ll be installing apps, tweaking settings, and of course creating lots of new documents and other data. This means that you should periodically create a fresh system image. Should disaster strike, you’ll be able to recover most of your system.

![]() On a Network Location—Select this option if you want to use a shared network folder. Either type the address of the share or click Select and then click Browse to use the Browse for Folder dialog box to choose the shared network folder. Make sure it’s a share for which you have permission to add data. Type a username and password for accessing the share, and then click OK.

On a Network Location—Select this option if you want to use a shared network folder. Either type the address of the share or click Select and then click Browse to use the Browse for Folder dialog box to choose the shared network folder. Make sure it’s a share for which you have permission to add data. Type a username and password for accessing the share, and then click OK.

4. The system image backup automatically includes your internal hard disk in the system image, and you can’t change that. However, if you also have external hard drives, you can add them to the backup by clicking their check boxes. Click Next. Windows Backup asks you to confirm your backup settings.

5. Click Start Backup. Windows Backup creates the system image.

6. Click OK.

If you used a hard drive and you have multiple external drives lying around, be sure to label the one that contains the system image so you’ll be able to find it later.

Protecting a File

Much day-to-day work in Windows 10 is required but not terribly important. Most memos, letters, and notes are run-of-the-mill and don’t require extra protection. Occasionally, however, you may create or work with a file that is important. It could be a carefully crafted letter, a memo detailing important company strategy, or a collection of hard-won brainstorming notes. Whatever the content, such a file requires extra protection to ensure that you don’t lose your work.

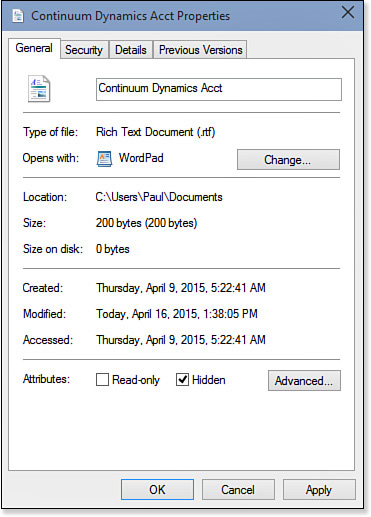

Making a File Read-Only

You can set advanced file permissions that can prevent a document from being changed or even deleted (see “Setting Security Permissions on Files and Folders,” later in the chapter). If your only concern is preventing other people from making changes to a document, a simpler technique you can use is making the document read-only. This means that although other people can make changes to a document, they cannot save those changes (except to a new file). The following steps show you how to make a file read-only:

1. Use File Explorer to open the folder that contains the file you want to protect.

2. Click the file.

3. In the Home tab, click the top half of the Properties button. The file’s Properties dialog box appears.

4. Click the General tab.

5. Check the Read-Only box, as shown in Figure 32.9.

6. Click OK. The file is now read-only.

To confirm that the file is protected, open it, make changes to the file, and then save it. The program displays the Save As dialog box. Click Save, and then when the programs asks if you want to overwrite the file, click Yes. Instead of overwriting the file, the program just tells you that the file is read-only.

Hiding a File

If you have a file that contains sensitive or secret data, making it read-only isn’t good enough because you probably don’t want unauthorized users to even see the contents of the file much less change them. To prevent other people from viewing a file, you can hide it so that it doesn’t appear during a cursory examination of the folder’s contents. Here are the steps to follow:

1. Use File Explorer to open the folder that contains the file you want to hide.

2. Click the file.

3. In the Home tab, click the top half of the Properties button. The file’s Properties dialog box appears.

4. Click the General tab.

5. Click the Hidden check box, as shown in Figure 32.10.

6. Click Advanced to open the Advanced Attributes dialog box.

7. Uncheck the Allow This File to Have Contents Indexed in Addition to File Properties box. This is optional, but it does prevent the file’s data from being found during a file search.

8. Click OK to return to the Properties dialog box.

9. Click OK. The file is now hidden.

To see a hidden file, first use File Explorer to open the folder containing the file. In the ribbon, click the View tab and then check the Hidden Items box.

Setting Security Permissions on Files and Folders

At the file system level, security for Windows 10 is most often handled by assigning permissions to a file or folder. Permissions specify whether a local user or group is allowed to access a file or folder and, if access is allowed, they also specify what the user or group is allowed to do with the file or folder. For example, a user may be allowed only to read the contents of a file or folder, whereas another may be allowed to make changes to the file or folder.

Windows 10 offers a basic set of six permissions for folders and five permissions for files:

![]() Full Control—A user or group can perform any of the actions listed. A user or group can also change permissions.

Full Control—A user or group can perform any of the actions listed. A user or group can also change permissions.

![]() Modify—A user or group can view the file or folder contents, open files, edit files, create new files and subfolders, delete files, and run programs.

Modify—A user or group can view the file or folder contents, open files, edit files, create new files and subfolders, delete files, and run programs.

![]() Read and Execute—A user or group can view the file or folder contents, open files, and run programs.

Read and Execute—A user or group can view the file or folder contents, open files, and run programs.

![]() List Folder Contents (folders only)—A user or group can view the folder contents.

List Folder Contents (folders only)—A user or group can view the folder contents.

![]() Read—A user or group can open files but cannot edit them.

Read—A user or group can open files but cannot edit them.

![]() Write—A user or group can create new files and subfolders as well as open and edit existing files.

Write—A user or group can create new files and subfolders as well as open and edit existing files.

There is also a long list of so-called special permissions that offer more fine-grained control over file and folder security. (We’ll run through these special permissions a bit later; see “Assigning Special Permissions.”)

Permissions are often handled most easily by using the built-in security groups. Each security group is defined with a specific set of permissions and rights, and any user added to a group is automatically granted that group’s permissions and rights. There are two main security groups:

![]() Administrators—Members of this group have complete control over the computer, meaning they can access all folders and files; install and uninstall programs (including legacy programs) and devices; create, modify, and remove user accounts; install Windows updates, service packs, and fixes; use Safe mode; repair Windows; take ownership of objects; and more.

Administrators—Members of this group have complete control over the computer, meaning they can access all folders and files; install and uninstall programs (including legacy programs) and devices; create, modify, and remove user accounts; install Windows updates, service packs, and fixes; use Safe mode; repair Windows; take ownership of objects; and more.

![]() Users—Members of this group (also known as standard users) can access files only in their own folders and in the computer’s shared folders, change their account’s password and picture, and run programs and install programs that don’t require administrative-level rights.

Users—Members of this group (also known as standard users) can access files only in their own folders and in the computer’s shared folders, change their account’s password and picture, and run programs and install programs that don’t require administrative-level rights.

In addition to those groups, Windows 10 also defines up to a dozen others that you’ll use less often (actually, most of these extra groups are of interest only to corporate IT personnel). Note that the permissions assigned to these groups are automatically assigned to members of the Administrators group. This means that if you have an Administrator account, you don’t also have to be a member of any other group to perform the tasks specific to that group. Here’s the list of groups:

![]() Access Control Assistance Operators—Members of this group can perform remote queries to determine the permissions assigned to a computer’s resources.

Access Control Assistance Operators—Members of this group can perform remote queries to determine the permissions assigned to a computer’s resources.

![]() Backup Operators—Members of this group can access the Backup program and use it to back up and restore folders and files, no matter what permissions are set on those objects.

Backup Operators—Members of this group can access the Backup program and use it to back up and restore folders and files, no matter what permissions are set on those objects.

![]() Cryptographic Operators—Members of this group can perform cryptographic tasks.

Cryptographic Operators—Members of this group can perform cryptographic tasks.

![]() Distributed COM Users—Members of this group can start, activate, and use Distributed COM (DCOM) objects.

Distributed COM Users—Members of this group can start, activate, and use Distributed COM (DCOM) objects.

![]() Event Log Readers—Members of this group can access and read Windows 10’s event logs.

Event Log Readers—Members of this group can access and read Windows 10’s event logs.

![]() Guests—Members of this group have the same privileges as those of the Users group. The exception is the default Guest account, which is not allowed to change its account password.

Guests—Members of this group have the same privileges as those of the Users group. The exception is the default Guest account, which is not allowed to change its account password.

![]() Hyper-V Administrators—Members of this group have complete access to all the features of the Hyper-V virtualization software.

Hyper-V Administrators—Members of this group have complete access to all the features of the Hyper-V virtualization software.

![]() IIS_IUSRS—Members of this group can access an Internet Information Server website installed on the Windows 10 computer.

IIS_IUSRS—Members of this group can access an Internet Information Server website installed on the Windows 10 computer.

![]() Network Configuration Operators—Members of this group have a subset of the administrator-level rights that enables them to install and configure networking features.

Network Configuration Operators—Members of this group have a subset of the administrator-level rights that enables them to install and configure networking features.

![]() Performance Log Users—Members of this group can use the Windows Performance Diagnostic Console snap-in to monitor performance counters, logs, and alerts, both locally and remotely.

Performance Log Users—Members of this group can use the Windows Performance Diagnostic Console snap-in to monitor performance counters, logs, and alerts, both locally and remotely.

![]() Performance Monitor Users—Members of this group can use the Windows Performance Diagnostic Console snap-in to monitor performance counters only, both locally and remotely.

Performance Monitor Users—Members of this group can use the Windows Performance Diagnostic Console snap-in to monitor performance counters only, both locally and remotely.

![]() Power Users—Members of this group have a subset of the Administrators group privileges. Power users can’t back up or restore files, replace system files, take ownership of files, or install or remove device drivers. In addition, power users can’t install applications that explicitly require the user to be a member of the Administrators group.

Power Users—Members of this group have a subset of the Administrators group privileges. Power users can’t back up or restore files, replace system files, take ownership of files, or install or remove device drivers. In addition, power users can’t install applications that explicitly require the user to be a member of the Administrators group.

![]() Remote Desktop Users—Members of this group can log on to the computer from a remote location using the Remote Desktop feature.

Remote Desktop Users—Members of this group can log on to the computer from a remote location using the Remote Desktop feature.

![]() Remote Management Users—Members of this group have access to Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) resources using Windows management protocols such as the Windows Remote Management service. Another group—WinRMRemoteWMIUsers—offers similar access.

Remote Management Users—Members of this group have access to Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) resources using Windows management protocols such as the Windows Remote Management service. Another group—WinRMRemoteWMIUsers—offers similar access.

![]() Replicator—Members of this group can replicate files across a domain.

Replicator—Members of this group can replicate files across a domain.

![]() System Managed Accounts Group—This group is used only for those accounts that are automatically created, modified, and deleted by Windows itself.

System Managed Accounts Group—This group is used only for those accounts that are automatically created, modified, and deleted by Windows itself.

Assigning a User to a Security Group

The advantage of using security groups to assign permissions is that once you set the group’s permissions on a file or folder, you never have to change the security again on that object. Instead, any new users you create, you assign to the appropriate security group, and they automatically inherit that group’s permissions.

Here are the steps to follow to assign a user to a Windows 10 security group:

1. Press Windows Logo+R to display the Run dialog box.

2. In the Open text box, type control userpasswords2.

3. Click OK. Windows 10 displays the User Accounts dialog box.

4. Click the user you want to work with, and then click Properties. The user’s property sheet appears.

5. Display the Group Membership tab.

7. Use the Other list to select the security group. Notice that Windows provides a short description of the selected group, as shown in Figure 32.11.

8. Click OK. Windows 10 assigns the user to the security group.

Assigning a User to Multiple Security Groups

If you want to assign a user to more than one security group, the User Account dialog box method that we ran through in the preceding section won’t work. If you have Windows 10 Pro or Enterprise, you can use the Local Users and Groups snap-in to assign a user to multiple groups. Here’s how:

1. In the taskbar’s Search box, type lusrmgr.msc and then press Enter. The Local Users and Groups snap-in appears.

2. Select the Users branch, and then double-click the user you want to work with. The user’s property sheet appears.

3. Display the Member Of tab, which displays the groups assigned to the user (see Figure 32.12).

4. Click Add. Windows 10 displays the Select Groups dialog box.

5. If you know the name of the group, type it in the large text box. Otherwise, click Advanced, Find Now, and then double-click the group in the list that appears.

6. Repeat step 5 to assign the user to other groups, as needed.

7. Click OK. Windows 10 adds the groups to the Member Of tab.

8. Click OK. Windows 10 assigns the user to the security groups the next time the user logs on.

Assigning Standard Permissions

When you’re ready to assign any of the standard permissions that we discussed earlier to a user or group, follow these steps:

1. In File Explorer, click the file or folder you want to secure.

2. Display the Home tab, and then click the top half of the Properties button to display the Properties dialog box.

3. Display the Security tab.

4. Click Edit. The Permissions for Object dialog box appears, where Object is the name of the file or folder.

5. Click Add to open the Select Users or Groups dialog box.

6. If you know the name of the user or group you want to add, type it in the large text box. Otherwise, click Advanced, Find Now, and then double-click the user or group in the list that appears.

7. Click OK. Windows 10 returns you to the Permissions for Object dialog box with the new user or group added.

8. Use the check boxes in the Allow and Deny columns to assign the permissions you want for this user or group, as shown in Figure 32.13.

Figure 32.13 Use a file or folder’s Permissions dialog box to assign standard permissions for a user or security group.

9. Click OK in all the open dialog boxes.

Assigning Special Permissions

In some situations, you might want more fine-tuned control over a user’s or group’s permissions. For example, you may want to allow a user to add new files to a folder, but not new subfolders. Similarly, you might want to give a user full control over a file or folder but deny that user the ability to change permissions or take ownership of the object.

For these more specific situations, Windows 10 offers a set of 14 special permissions for folders and 13 special permissions for files:

![]() Full Control—A user or group can perform any of the actions listed here.

Full Control—A user or group can perform any of the actions listed here.

![]() Traverse Folder/Execute File—A user or group can open the folder to get to another folder or can execute a program file.

Traverse Folder/Execute File—A user or group can open the folder to get to another folder or can execute a program file.

![]() List Folder/Read Data—A user or group can view the folder contents or can read the contents of a file.

List Folder/Read Data—A user or group can view the folder contents or can read the contents of a file.

![]() Note

Note

To see a file’s or folder’s attributes, right-click the item, click Properties, and then display the General tab.

![]() Read Attributes—A user or group can read the folder’s or file’s attributes, such as Read-Only or Hidden.

Read Attributes—A user or group can read the folder’s or file’s attributes, such as Read-Only or Hidden.

![]() Read Extended Attributes—A user or group can read the folder’s or file’s extended attributes. (These are extra attributes assigned by certain programs.)

Read Extended Attributes—A user or group can read the folder’s or file’s extended attributes. (These are extra attributes assigned by certain programs.)

![]() Create Files/Write Data—A user or group can create new files within a folder or can make changes to a file.

Create Files/Write Data—A user or group can create new files within a folder or can make changes to a file.

![]() Create Folders/Append Data—A user or group can create new subfolders within a folder or can add new data to the end of a file (but can’t change any existing file data).

Create Folders/Append Data—A user or group can create new subfolders within a folder or can add new data to the end of a file (but can’t change any existing file data).

![]() Write Attributes—A user or group can change the folder’s or file’s attributes.

Write Attributes—A user or group can change the folder’s or file’s attributes.

![]() Write Extended Attributes—A user or group can change the folder’s or file’s extended attributes.

Write Extended Attributes—A user or group can change the folder’s or file’s extended attributes.

![]() Delete Subfolders and Files—A user or group can delete subfolders and files within the folder.

Delete Subfolders and Files—A user or group can delete subfolders and files within the folder.

![]() Delete—A user or group can delete the folders or file.

Delete—A user or group can delete the folders or file.

![]() Read Permissions—A user or group can read the folder’s or file’s permissions.

Read Permissions—A user or group can read the folder’s or file’s permissions.

![]() Change Permissions—A user or group can edit the folder’s or file’s permissions.

Change Permissions—A user or group can edit the folder’s or file’s permissions.

![]() Take Ownership—A user or group can take ownership of the folder or file.

Take Ownership—A user or group can take ownership of the folder or file.

Here are the steps to follow to assign special permissions to a file or folder:

1. In File Explorer, click the file or folder you want to secure.

2. Display the Home tab, and then click the top half of the Properties button.

3. Display the Security tab.

4. Click Advanced. The Advanced Security Settings for Object dialog box appears, where Object is the name of the file or folder.

5. In the Permissions tab, click Add. The Permission Entry for Object dialog box appears.

6. Click Select a Principal.

7. If you know the name of the user or group you want to work with, type it in the large text box. Otherwise, click Advanced, Find Now, and then double-click the user or group in the list that appears.

8. Click Show Advanced Permissions.

9. In the Type list, select either Allow or Deny.

10. Use the check boxes to assign the permissions you want for this user or group, as shown in Figure 32.14.

Figure 32.14 Use a file or folder’s Permission Entry dialog box to assign special permissions for a user or security group.

11. Click OK in all the open dialog boxes.

Fixing Permission Problems by Taking Ownership of Your Files

When you’re working in Windows 10, you might have trouble with a folder (or a file) because Windows tells you that you don’t have permission to edit (add to, delete, whatever) the folder. The result is often a series of annoying User Account Control dialog boxes.

You might think the solution is to give your user account Full Control permissions on the folder, but it’s not as easy as that. Why not? Because you’re not the owner of the folder. (If you were, you’d have the permissions you need automatically.) So the solution is to first take ownership of the folder, and then assign your user account full control permissions over the folder.

Here are the steps to follow:

1. Use File Explorer to locate the folder you want to take ownership of.

2. Display the Home tab, and then click the top half of the Properties button.

3. Display the Security tab.

4. Click Advanced to open the Advanced Security Settings dialog box.

5. Display the Permissions tab.

6. Click the Change link that appears beside the current owner. The Select User or Group dialog box appears.

7. Type your username, and then click OK.

8. Check the Replace Owner on Subcontainers and Objects box, as shown in Figure 32.15.

9. Click OK to return to the Security tab of the folder’s Properties dialog box.

10. If you don’t see your user account in the Group or User Names list, click Edit, click Add, type your username, and click OK.

11. Click your username.

12. Click the Full Control check box in the Allow column.

13. Click OK.

Note that, obviously, this is quite a bit of work. If you have to do it only every once in a while, it’s no big thing, but if you find you have to take ownership regularly, you’ll probably want an easier way to go about it. You’ve got it! Listing 32.1 shows a Registry Editor file that modifies the Registry in such a way that you end up with a Take Ownership command in the shortcut menu that appears if you right-click any folder and any file.

Listing 32.1 A Registry Editor File That Creates a Take Ownership Command

Windows Registry Editor Version 5.00

[HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT*shell

unas]

@="Take Ownership"

"NoWorkingDirectory"=""

[HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT*shell

unascommand]

@="cmd.exe /c takeown /f "%1" && icacls "%1" /grant administrators:F"

"IsolatedCommand"="cmd.exe /c takeown /f "%1" && icacls "%1" /grant administrators:F"

[HKEY_CLASSES_ROOTDirectoryshell

unas]

@="Take Ownership"

"NoWorkingDirectory"=""

[HKEY_CLASSES_ROOTDirectoryshell

unascommand]

@="cmd.exe /c takeown /f "%1" /r /d y && icacls "%1" /grant administrators:F /t"

"IsolatedCommand"="cmd.exe /c takeown /f "%1" /r /d y && icacls "%1" /grant administrators:F /t"

To use the file, double-click it and then enter your UAC credentials when prompted. As you can see in Figure 32.16, right-clicking (in this case) a folder displays a shortcut menu with a new Take Ownership command. Click that command, enter your UAC credentials, and sit back as Windows does all the hard work for you!

Figure 32.16 When you install the Registry modification, you see the Take Ownership command when you right-click a file.

Encrypting Files and Folders

If a snoop can’t log on to your Windows PC, does that mean your data is safe? No, unfortunately, it most certainly does not. If a cracker has physical access to your PC—either by sneaking into your office or by stealing your computer—the cracker can use advanced utilities to view the contents of your hard drive. This means that if your PC contains extremely sensitive or confidential information—personal financial files, medical histories, corporate salary data, trade secrets, business plans, journals or diaries—it wouldn’t be hard for the interloper to read and even copy that data.

![]() Note

Note

To use file encryption, the drive must use NTFS. To check the current file system, open File Explorer, click This PC, click the drive, select Computer, Properties, and in the General tab, examine the file system information in the Properties dialog box. If you need to convert a drive to NTFS, press Windows Logo+X, click Command Prompt (Admin), and then click Yes when User Account Control asks you to confirm. At the command prompt, type convert d: /fs:ntfs, where d is the letter of the hard drive you want to convert, and press Enter. If Windows asks to “dismount the volume,” press Y and then Enter.

If you’re worried about anyone viewing these or other “for your eyes only” files, Windows 10 Pro enables you to encrypt the file information. Encryption encodes the file to make it completely unreadable by anyone unless the person logs on to your Windows 10 account. After you encrypt your files, you work with them exactly as you did before, with no noticeable loss of performance.

Encrypting a Folder

Follow these steps to encrypt important data:

1. Use File Explorer to display the icon of the folder containing the data that you want to encrypt.

![]() Tip

Tip

Although it’s possible to encrypt individual files, encrypting an entire folder is easier because Windows 10 then automatically encrypts new files that you add to the folder.

2. In the Home tab, click the top half of the Properties button to open the folder’s property sheet.

3. Click the General tab.

4. Click Advanced. The Advanced Attributes dialog box appears.

5. Click to activate the Encrypt Contents to Secure Data check box.

6. Click OK in each open dialog box. The Confirm Attribute Changes dialog box appears.

7. Click the Apply Changes to This Folder, Subfolders and Files option.

8. Click OK. Windows encrypts the folder’s contents.

By default, Windows displays the names of encrypted files and folders in a green font, which helps you to differentiate these items from unencrypted files and folders. If you’d rather see encrypted filenames and folder names in the regular font, open any folder window and select View, Options. Click the View tab, click to uncheck the Show Encrypted or Compressed NTFS Files in Color box, and then click OK.

Backing Up Your Encryption Key

When you sign in to Windows 10, it uses your credentials to access the encryption key that decrypts the folder so you can access it. This encryption key is stored on your hard disk for easy and fast access. However, like any file or folder on your hard disk, the encryption key can become corrupted. If that happens, you lose access to the encrypted data, so key corruption is a disaster waiting to happen. To avoid that disaster, you should back up the encryption key to a removable drive for safekeeping.

When you encrypt a folder for the first time, Windows 10 displays a notification suggesting you back up the encryption key, as shown in Figure 32.17. Click that notification to get started. If you miss the notification, click the Show Hidden Icons arrow in the taskbar’s notification area, and then click the Encrypting File System icon.

Figure 32.17 When you first use the encrypting file system, you see this notification prompting you to back up your encryption key.

Follow these steps to back up your encryption key to a removable drive:

1. In the initial Encrypting File System dialog box, click Back Up Now. The Certificate Export Wizard appears.

2. Click Next. The Export File Format dialog box appears.

3. The default format is fine, so click Next. The Security dialog box appears and prompts you for a password to protect the encryption key.

4. Check the Password text box, type the password in both the Password text box and then the Confirm Password text box, and then click Next. The File to Export dialog box appears.

5. Insert a removable drive, such as a USB flash drive.

6. Click Browse, click This PC, double-click the removable drive, type a filename, and then click Save.

7. Click Next.

8. Click Finish, and then click OK when the wizard tells you the export was successful.

Encrypting a Disk with BitLocker

Take Windows 10 security technologies such as the bidirectional Windows Firewall, Windows Defender, and Windows Service Hardening; throw in good patch-management policies (that is, applying security patches as soon as they’re available); and add a dash of common sense. If you do so, your computer should never be compromised by malware while Windows 10 is running.

However, what about when Windows 10 is not running? If your computer is stolen or if an attacker breaks into your home or office, your machine can be compromised in a couple of different ways:

![]() By booting to a removable drive and using command-line utilities to reset the administrator password

By booting to a removable drive and using command-line utilities to reset the administrator password

![]() By using a removable drive–based operating system to access your hard disk and reset folder and file permissions

By using a removable drive–based operating system to access your hard disk and reset folder and file permissions

Either exploit gives the attacker access to the contents of your computer. If you have sensitive data on your machine—financial data, company secrets, and so on—the results could be disastrous.

![]() Note

Note

To find out whether your computer has a TPM chip installed, restart the machine and then access the computer’s BIOS settings (usually by pressing Delete or some other key; watch for a startup message that tells you how to access the BIOS). In most cases, look for a Security section and see if it lists a TPM entry.

To help you prevent a malicious user from accessing your sensitive data, Windows 10 Pro (as well as the Enterprise and Education editions and possibly Windows 10 Home, depending on whether your PC setup can handle encryption) comes with a technology called BitLocker that encrypts an entire hard drive. That way, even if a malicious user gains physical access to your computer, he won’t be able to read the drive contents. BitLocker works by storing the keys that encrypt and decrypt the sectors on a system drive in a Trusted Platform Module (TPM) 1.2 chip, which is a hardware component available on many newer machines.

Enabling BitLocker on a System with a TPM

To enable BitLocker on a system that comes with a TPM, use the taskbar’s Search box to type bit, and then click Manage BitLocker. In the BitLocker Drive Encryption window, shown in Figure 32.18, click the Turn On BitLocker link associated with your hard drive.

![]() Note

Note

You can also use the Trusted Platform Module (TPM) Management snap-in to work with the TPM chip on your computer. If you’re in the BitLocker Drive Encryption window, click TPM Administration. Otherwise, use the taskbar’s Search box to type tpm.msc and then press Enter. This snap-in enables you to view the current status of the TPM chip, view information about the chip manufacturer, and perform chip-management functions.

Enabling BitLocker on a System Without a TPM

If your PC doesn’t have a TPM chip, you can still use BitLocker. In this case, however, you’ll be forced to jump an extra hurdle when you start your computer. This hurdle will either be an extra password that you must enter or a USB flash drive that you must insert. Only by doing this will Windows 10 decrypt the drive and enable you to work with your computer in the normal way.

First, you must configure Windows 10 to allow BitLocker on a system without a TPM. Here’s how it’s done:

1. In the taskbar’s Search box, type gpedit.msc and then press Enter to open the Local Group Policy Editor.

2. Open the Computer Configuration, Administrative Templates, Windows Components, BitLocker Drive Encryption, Operating System Drives branch.

3. Double-click the Require Additional Authentication at Startup policy.

4. Select Enabled.

5. Click to check the Allow BitLocker Without a Compatible TPM box, as shown in Figure 32.19.

Figure 32.19 Use the Require Additional Authentication at Startup policy to configure Windows 10 to use BitLocker without a TPM.

6. Click OK.

7. To ensure that Windows 10 recognizes the new policy right away, press Windows Logo+R to open the Run dialog box, type gpupdate /force, and click OK.

If your version of Windows 10 doesn’t offer the Local Group Policy Editor, you can still configure BitLocker to work on non-TPM systems by editing the Registry. However, this requires creating and configuring a new Registry key and a half dozen settings. To make this easier, we created a REG file that does everything automatically. You can download this file from www.mcfedries.com/book.php?title=windows-10-in-depth.

You can now enable BitLocker:

1. In the taskbar’s Search box, type bitl and then click Manage BitLocker to open the BitLocker Drive Encryption window.

2. Click the Turn On BitLocker link beside your hard drive. The BitLocker Drive Encryption Wizard appears and asks how you want to unlock your drive when you start the system.

3. Make your choice:

![]() Insert a USB Flash Drive—Click this option to require a flash drive to be inserted at startup. Insert the flash drive, wait until the wizard recognizes it, and then click Save.

Insert a USB Flash Drive—Click this option to require a flash drive to be inserted at startup. Insert the flash drive, wait until the wizard recognizes it, and then click Save.

![]() Enter a Password—Click this option to require a password at startup. Type your password in the two text boxes, and then click Next.

Enter a Password—Click this option to require a password at startup. Type your password in the two text boxes, and then click Next.

4. The wizard now asks how you want to store your recovery key, which you’ll need if you ever have trouble unlocking your PC. Click one (or more) of the following options:

![]() Save to your Microsoft account—Click this option to save the recovery key as part of your Microsoft account.

Save to your Microsoft account—Click this option to save the recovery key as part of your Microsoft account.

![]() Save to a USB Flash Drive—Click this option to save the recovery key to a flash drive. This is probably the best way to go because it means you can recover your files just by inserting the flash drive. Insert the flash drive, select it in the list that appears, and then click Save.

Save to a USB Flash Drive—Click this option to save the recovery key to a flash drive. This is probably the best way to go because it means you can recover your files just by inserting the flash drive. Insert the flash drive, select it in the list that appears, and then click Save.

![]() Save to a File—Click this option to save the recovery key to a separate hard drive on your system. Use the Save BitLocker Recovery Key As dialog box to choose a location, and then click Save.

Save to a File—Click this option to save the recovery key to a separate hard drive on your system. Use the Save BitLocker Recovery Key As dialog box to choose a location, and then click Save.

![]() Print the Recovery Key—Click this option to print out the recovery key. Choose your printer in the dialog box that appears, and then click Print.

Print the Recovery Key—Click this option to print out the recovery key. Choose your printer in the dialog box that appears, and then click Print.

5. Click Next. The wizard asks how much of your drive you want to encrypt.

6. Select an option:

![]() Encrypt Used Disk Space Only—This option encrypts only the current data on the drive; any new data you add gets encrypted automatically. This is a much faster option, but it might not give you total protection if you’ve been using your PC for a while.

Encrypt Used Disk Space Only—This option encrypts only the current data on the drive; any new data you add gets encrypted automatically. This is a much faster option, but it might not give you total protection if you’ve been using your PC for a while.

![]() Encrypt Entire Drive—This option encrypts both the current data on the drive and the drive’s empty space. This takes quite a bit longer, but it offers total security because it also encrypts deleted data that remains on the hard drive and could otherwise be read by a snoop with low-level file utilities.

Encrypt Entire Drive—This option encrypts both the current data on the drive and the drive’s empty space. This takes quite a bit longer, but it offers total security because it also encrypts deleted data that remains on the hard drive and could otherwise be read by a snoop with low-level file utilities.

7. Click Next. The wizard lets you know that BitLocker now needs to be activated.

8. Make sure the Run BitLocker System Check setting is activated, and then click Continue. BitLocker tells you your system won’t be encrypted until you restart.

9. Restart your PC.

10. If you chose to enter a password at startup, you see the BitLocker screen shown in Figure 32.20. Type your BitLocker password and press Enter. If you chose a flash drive startup, make sure the flash drive is inserted.

Figure 32.20 If you chose to enter a password at startup, use this screen to type the password, and then press Enter.

11. Sign in to Windows 10. BitLocker begins encrypting your hard drive.