19. Connecting Your Network to the Internet

Sharing an Internet Connection

The preceding chapter shows how to create an inexpensive local area network (LAN) to tie your computers together. With a network in place, a single high-speed Internet connection can serve all the computers in your home or office, or you can share a modem connection made from one designated Windows computer.

A shared Internet connection can actually provide better protection against hackers than can an individual connection, because a shared connection must funnel through a router device or a software service that blocks outside attempts to connect to your computers—except on your terms. In this chapter, we show you how to set this up.

![]() Note

Note

You should also read Chapter 33, “Protecting Your Network from Hackers and Snoops,” for more details on protecting your network from hacking.

Selecting a Way to Make the Connection

When you’re using a single computer, you mostly likely use a broadband cable, DSL, or satellite modem to connect to your ISP as needed. (Cellular data and old-fashioned dial-up services are also possibilities, but fairly rare for home and small office computers.) To share your Internet service with other computers, using a network, you can use an inexpensive hardware device called a router or residential gateway to serve as a bridge between your network and a cable or DSL modem. Your ISP might have provided you with a router, but if it didn’t, adding one is easy and inexpensive. The router then automatically manages your Internet connection.

As an overview, Figure 19.1 shows three ways to hook up the computers on your LAN to an Internet service provider (ISP). Throughout this chapter, we refer to these as schemes A, B, and C. They are as follows:

A. Router with a broadband modem—A router enables a single Internet connection to be shared with multiple computers. This method is more secure than directly connecting your computer to the modem because the router shields Windows from the Internet.

A Wi-Fi router, which will provide both wireless (Wi-Fi) and plug-in Ethernet connections, will give you the most flexibility.

B. Cable modem, multiple computers—This setup that some cable ISPs recommend for a home with more than one computer is a bad idea. You can’t use this method and also use file and printer sharing. Use scheme A or C. See “Special Notes for Cable Service,” later in this chapter, for more information.

C. Combination Router/Modem—Some ISPs provide a device that combines the functions of a modem and router in the same package. Again, it’s best if the device supports both Wi-Fi and Ethernet connections.

Now let’s look at the issues involved in having a single ISP connection serve multiple computers.

Managing IP Addresses

Connecting a LAN to the Internet requires you to delve into some issues about how computers are identified on your LAN and on the Internet. Each computer on your LAN uses a unique network identification number called an IP address that is used to route data to the correct computer. As long as the data stays on your LAN, it doesn’t matter what numbers are used; your LAN is essentially a private affair.

When you connect to the Internet, though, those random numbers can’t be used to direct data to you; your ISP must assign a public IP address to you so that other computers on the Internet can properly route data to your ISP and then to you.

Now, when you establish a solo connection from your computer to the Internet, this isn’t a big problem. When you connect, your ISP assigns your computer a temporary public IP address. Any computer on the Internet can send data to you using this address. When you want to connect a LAN, though, it’s not quite as easy. Two approaches are used:

![]() You can get a valid public IP address for each of your computers.

You can get a valid public IP address for each of your computers.

![]() You can use one public IP address and share it among all the users of your LAN.

You can use one public IP address and share it among all the users of your LAN.

The first approach is called routed Internet service because your ISP assigns a set of consecutive IP addresses for your LAN—one for each of your computers—and routes all data for these addresses to your site. This can be done using a specially configured router and usually incurs extra monthly charges for each IP address beyond the first.

The second approach is by far the most common for home and small office use and uses a technique called Network Address Translation (NAT), in which all the computers on your LAN share one public IP address and connection.

NAT and Internet Connection Sharing

The popular routers used in homes and small offices are also called residential gateways or, if they have Wi-Fi capability, wireless routers. As mentioned in the previous section, in almost all cases they are set up to use NAT to establish all Internet connections using one public IP address. The computer or device running the NAT service mediates all connections between computers on your LAN and the Internet (see Figure 19.2).

Figure 19.2 A NAT device or program carries out all Internet communications using one IP address. NAT keeps track of outgoing data from your LAN to determine where to send responses from the outside.

NAT works a lot like mail delivery to a large commercial office building, where there’s one address for many people. Mail is delivered to the mail room, which sorts it and delivers it internally to the correct recipient. With NAT, your router is assigned one public IP address, and all communication between your LAN and the Internet uses this address. The NAT service takes care of changing or translating the IP addresses in data packets from the private, internal IP addresses used on your LAN to the one public address used on the Internet and forwards data from the outside world to your computers.

Using NAT has several significant consequences:

![]() You can hook up as many computers on your LAN as you want. Your ISP won’t care, or even know, that more than one computer is using the connection. You save money because you pay for only a single connection. (On the other hand, if you have a metered Internet connection, such as satellite data service, this means everyone is eating away at your quota.)

You can hook up as many computers on your LAN as you want. Your ISP won’t care, or even know, that more than one computer is using the connection. You save money because you pay for only a single connection. (On the other hand, if you have a metered Internet connection, such as satellite data service, this means everyone is eating away at your quota.)

![]() You can assign IP addresses inside your LAN however you want. In fact, all the NAT setups we’ve seen provide DHCP, an automatic IP addressing system, so virtually no manual configuration is needed on the computers you add to your LAN. Just plug in a computer, and it’s on the Internet.

You can assign IP addresses inside your LAN however you want. In fact, all the NAT setups we’ve seen provide DHCP, an automatic IP addressing system, so virtually no manual configuration is needed on the computers you add to your LAN. Just plug in a computer, and it’s on the Internet.

![]() If you want to host a website, VPN, or other service on your LAN and make it available from the Internet, you have some additional setup work to do. When you contact a remote website, NAT knows to send the returned data back to you, but when an unsolicited request comes from outside, NAT must be told where to send the incoming connection. We discuss this scenario later in the chapter.

If you want to host a website, VPN, or other service on your LAN and make it available from the Internet, you have some additional setup work to do. When you contact a remote website, NAT knows to send the returned data back to you, but when an unsolicited request comes from outside, NAT must be told where to send the incoming connection. We discuss this scenario later in the chapter.

![]() NAT serves as an additional firewall to protect your LAN from probing by Internet hackers. Incoming requests, such as those to read your shared folders, are simply ignored if you haven’t specifically set up your connection-sharing service to forward requests to a particular computer.

NAT serves as an additional firewall to protect your LAN from probing by Internet hackers. Incoming requests, such as those to read your shared folders, are simply ignored if you haven’t specifically set up your connection-sharing service to forward requests to a particular computer.

![]() Some network services can’t be made to work with NAT. For example, you might not be able to use some audio and video chat services. These programs expect that the IP address of the computer on which they’re running is a public address. Windows ICS and some hardware-sharing routers can sometimes work around this problem using the Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) protocol, which is discussed later in the chapter.

Some network services can’t be made to work with NAT. For example, you might not be able to use some audio and video chat services. These programs expect that the IP address of the computer on which they’re running is a public address. Windows ICS and some hardware-sharing routers can sometimes work around this problem using the Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) protocol, which is discussed later in the chapter.

![]() Note

Note

With every version of Windows starting with Windows 98, Microsoft has provided a feature called Internet Connection Sharing (ICS), which lets one designated computer on your network perform the function of a NAT router. Windows 10 includes this capability, but we can’t recommend that you use it. To use ICS, you must leave one of your Windows computers turned on so that other computers can reach the Internet. Connection-sharing routers must be left on, too, but they consume very little power compared to what a PC sucks up. Routers are inexpensive, easy to use, and with most offering Wi-Fi service as well, they are much better option for sharing an Internet connection than using ICS.

If your ISP doesn’t provide a combination modem/router and you need to get one, look at the products made by Linksys, D-Link, SMC, and Netgear. You can find them at computer stores, office supply stores, and online. On sale you can pick one up for as little as $20 or less. Wireless versions that include an 802.11n or 802.11g wireless networking base station as well as a switch for wired Ethernet connections don’t cost that much more. The latest standard for Wi-Fi routers is 802.11ac, and these can transfer data much faster than 802.11n or g, but they cost somewhat more.

More advanced (and expensive) versions include additional features such as a built-in print server and virtual private networking (VPN) service.

The next section discusses issues that are important to business users. If you’re setting up a network for your home, you can skip ahead.

Special Notes for Wireless Networking

If you’re setting up a router that provides wireless (Wi-Fi) networking, you must enable wireless data encryption to protect your network from unexpected use by random strangers. People connecting to your wireless network appear to Windows to be part of your own LAN and are trusted accordingly.

![]() To learn more about setting up a secure wireless network, see “Installing a Wireless Network,” p. 390.

To learn more about setting up a secure wireless network, see “Installing a Wireless Network,” p. 390.

If you really want to provide free access to your broadband connection as a public service, be sure to use a wireless router that can automatically provide a separate Guest network; computers connecting to the Guest network can’t access your or any other computers on the network, just outside Internet servers. Alternatively, provide public access using a second, unsecured wireless router plugged in to your network, as shown in Figure 19.3. Use a different channel number and network name (SSID) from the ones set up for your private wireless LAN. Set up filtering in this router to prevent Windows file-sharing queries from penetrating into your own network. See “Routed Service with Multiple Addresses,” later in this chapter, for the list of ports you must block.

Figure 19.3 If you want to provide unsecured, free wireless Internet access to strangers, you can use a second wireless router to protect your own LAN. Windows File Sharing services don’t cross the barrier provided by a NAT router.

(And remember that someone might use your public connection to send spam or attack other networks. If the FBI knocks on your door some day, don’t say we didn’t warn you.)

Special Notes for Cable Service

Some cable ISPs can provide you with multiple IP addresses so you can connect multiple computers directly to your cable modem using a simple Ethernet switch, and no router. This is scheme B in Figure 19.1. It’s a very simple setup, but we strongly urge you not to use this type of service. Because all of your computers would be directly exposed to the Internet, without the barrier provided by a NAT router, it’s not safe to enable and use file and printer sharing on such a network.

![]() Caution

Caution

The scheme B setup requires you to connect your cable modem directly to your LAN, without any firewall protection between the Internet and your computers. If you use this scheme, you must disable file and printer sharing on each computer. In Windows parlance, you must designate your network a public network. If you don’t, you would expose all your computers to a severe security risk.

(Now, some ISPs provide you with a combination modem and router in one box. That would be fine; there’s still a router in place, and you have scheme C. What we’re talking about here is a plain cable modem without a router.)

If you want to take full advantage of having a LAN in your home or office, use scheme A instead. Simply add an inexpensive connection-sharing router—for as little as $20, as mentioned previously—and you’ll get all the benefits of a LAN without the risks of a direct connection.

Configuring Your LAN

In the following sections, we describe how to set up each of the connection schemes diagrammed in Figure 19.1. If you’re still in the planning stages for your network, you might want to read all the sections to see what’s involved; this information might help you decide what configuration you want to use. If your LAN is already set up and your Internet service is ready to go now, just skip ahead to the appropriate section.

Scheme A—Router with a Broadband Modem

This section shows how to set up the Internet connection method illustrated in Figure 19.1 as scheme A. Your router’s manufacturer will provide instructions for installing and configuring it. You might want to first connect the modem directly to one of your computers to make sure your service works. (We discuss how to set up directly connected Internet service in Chapter 14, “Getting Connected.”) Then, connect the modem and your computer(s) to your router following the manufacturer’s instructions, and set up the router.

If you’re using cable or DSL Internet service, you’ll connect your broadband modem to the router using a short Ethernet patch cable.

Then, you’ll connect the router to your other computers using one of the two methods shown in Figure 19.4.

You then configure the router, telling it how to contact your ISP and what range of IP addresses to serve up to your LAN. Every device will use a different procedure, so you will have to follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

If your ISP uses PPPoE (broadband service that requires a username and password to establish the connection) to establish a connection, you must set up your router to enable PPPoE, and store your logon and password in the router. Some DSL service works this way. If your DSL provider does use PPPoE, you should enable the router’s auto-sign-on feature, and you can optionally set up a “keepalive” value that will tell the modem to periodically send network traffic even if you don’t, to keep your connection active all the time.

![]() Caution

Caution

Be sure to change your router’s factory-supplied password after you install it. (And write the password somewhere in the router’s manual, or put it on a sticky label on the bottom of the router.) Also, be sure to disable outside (Internet) access to the router’s management screens.

If you use cable Internet service and your ISP didn’t provide you with a special hostname that you had to give to your computer, your ISP probably identifies you by your network adapter’s MAC (hardware) address. You might find that your Internet connection won’t work when you set up the router. One of your router’s setup pages should show you its MAC address. You can either call your ISP’s customer service line and tell them that this is your new adapter’s MAC address, or configure the router to “clone” your computer’s MAC address—that is, copy the address from the computer you originally used to set up your cable connection. Your router’s setup manual should tell you how to do this.

As you are configuring your router, you might want to enable Universal Plug and Play, discussed later in this chapter.

You might also opt for even better hacker protection by having your router filter (block) Microsoft file and printer sharing data. You usually do this on an advanced setup screen labeled Filtering. See “Routed Service with Multiple Addresses,” later in this chapter, for the list of ports that you must block. Figure 19.6 at the end of this chapter shows filtering set up on one common brand of router.

![]() If your router has wireless networking capability, to learn how to set that part up, see “Installing a Wireless Network,” p. 390.

If your router has wireless networking capability, to learn how to set that part up, see “Installing a Wireless Network,” p. 390.

When the router has been set up, go to each of your computers and follow the instructions under “Configuring the Rest of the Network,” later in this chapter.

Scheme B—Cable Modem, Multiple Computers

This section discusses the Internet connection method illustrated in Figure 19.1 as scheme B. This setup is comparable to having all of your computers and devices connected through a public, insecure network in a coffee shop or airport. So, as mentioned earlier in the chapter, you cannot safely use file and printer sharing with this setup. Use this setup only if you don’t want file and printer sharing and just want to have several computers with Internet access.

In this configuration, follow your ISP’s instructions for setting up each computer separately. The only unusual thing here is that the computers plug into a switch or hub, and the switch or hub plugs into the cable modem; otherwise, each computer is set up exactly as if it was a completely separate, standalone computer with cable Internet service.

![]() Caution

Caution

If you do use this scheme, on each Windows computer (Windows Vista and higher), you must set the network location for the connection that goes to your switch and cable modem to Public Network. Windows XP and earlier versions are no longer supported and are not safe to use with this kind of direct Internet connection no matter how they’re set up.

To verify whether the network location is set to Public Network on Windows 10, follow these steps:

1. Right-click the network icon at the right end of the taskbar. Select Open Network and Sharing Center.

2. Check that the label under your network connection is labeled Public Network. If it is, you can stop here. If it’s not, continue with step 3.

3. Click the Network icon in the taskbar and select Network Settings. If Ethernet is not selected at the left, select it now. At the right, click your network connection’s icon. Scroll down and click Advanced Options, and then turn off Find Devices and Content.

If you later decide that you want to use file and printer sharing, do not simply turn Find Devices and Content back on, or enable file and printer sharing, or create a homegroup. Instead, set up a router as in scheme A.

Scheme C—Combination Router/Modem

This section discusses setting up the Internet connection method illustrated in Figure 19.1 as scheme C, using a device that is both a broadband mode and a router. Your ISP should provide instructions for installing and configuring this device.

You can also follow the procedure under “Scheme A—Router with a Broadband Modem,” earlier in this chapter, except that you can skip the first two paragraphs because you don’t have a separate modem to test, and you don’t have to use a cable to connect your modem and router.

When the router has been set up, go to each of your computers and follow the instructions under “Configuring the Rest of the Network,” later in this chapter.

Routed Service with Multiple Addresses

If you need to have fixed, public IP addresses for multiple computers on your network, you need what is called routed Internet service, where your ISP assigns you more than one fixed IP address. This isn’t a common requirement for homes or even small businesses, unless you run multiple computers that offer the same services (with the same network port numbers), and they have to be accessible by the public. If you need this type of Internet service, you already know it. Routed service can be obtained with business class cable or DSL service, Frame Relay, ATM, or other technologies.

The wiring will look like either Figure 19.1 scheme A or C. Routed service requires a more fully featured router than the inexpensive residential gateways we discuss in this chapter. In some cases, though, a standard a combination modem/router can do the job. Your ISP can help you decide what equipment is needed.

If you get this type of service, you have something that is functionally similar to Scheme B, in which your computers and your LAN are directly exposed to the Internet. Unlike scheme B, which has no router, you can use file and printer sharing safely, but only if your router is carefully configured to filter and block all incoming network traffic except for that directed at the ports that you need to support for your public services. Setting up this kind of filtering is beyond the scope of this book and is best set up by a networking professional or, if you completely trust them, your ISP’s tech support staff.

![]() Caution

Caution

If your router is not properly configured to filter out NetBIOS traffic, your network will be exposed to hackers. After setting things up, visit www.grc.com and use the ShieldsUP pages there to be sure your computers are properly protected. For more information about network security, see Chapter 33.

To repeat, it is absolutely essential that your router be set up to protect your network. You must ensure that at least these three items are taken care of:

![]() The router must be set up with filters to prevent Microsoft file-sharing service (NetBIOS and NetBT) packets from entering or leaving your LAN. In technical terms, the router must be set up to block TCP and UDP on port 137, UDP on port 138, and TCP on ports 139 and 445. It should “drop” rather than “reject” packets, if possible. This helps prevent hackers from discovering that these services are present but blocked. Better to let them think they’re not there at all.

The router must be set up with filters to prevent Microsoft file-sharing service (NetBIOS and NetBT) packets from entering or leaving your LAN. In technical terms, the router must be set up to block TCP and UDP on port 137, UDP on port 138, and TCP on ports 139 and 445. It should “drop” rather than “reject” packets, if possible. This helps prevent hackers from discovering that these services are present but blocked. Better to let them think they’re not there at all.

![]() Be absolutely sure to change your router’s administrative password from the factory default value to something hard to guess, with uppercase letters, lowercase letters, numbers, and punctuation. Don’t let your ISP talk you out of this. Also, you should let them know what the new password is so they can get into the router from their end, if needed.

Be absolutely sure to change your router’s administrative password from the factory default value to something hard to guess, with uppercase letters, lowercase letters, numbers, and punctuation. Don’t let your ISP talk you out of this. Also, you should let them know what the new password is so they can get into the router from their end, if needed.

![]() Disable SNMP access, or change the SNMP read and read-write “community names” to something other than the default. Again, use something with letters, numbers, and punctuation.

Disable SNMP access, or change the SNMP read and read-write “community names” to something other than the default. Again, use something with letters, numbers, and punctuation.

Second, either your ISP will set up your router to automatically assign network addresses to your computers using DHCP, or you will have to manually set up a fixed IP address for each computer, using the IP address, network mask, gateway address, and DNS server addresses supplied by your ISP. Be absolutely sure that Windows Firewall, or a comparable third-party firewall service is installed on each of your computers.

Universal Plug and Play

Your router might have a feature called Universal Plug and Play (UPnP). UPnP provides a way for software running on your computer to communicate with the router. Specifically, UPnP provides a means for the following:

![]() The router to tell software on your computer that it is separated from the Internet by NAT. This may let some software—the video and audio parts of most messaging programs, in particular—have a better chance of working.

The router to tell software on your computer that it is separated from the Internet by NAT. This may let some software—the video and audio parts of most messaging programs, in particular—have a better chance of working.

![]() Software running on the network to tell the router to forward expected incoming connections to the correct computer. Online messaging programs often require this. When the computer on the other end of the connection starts sending data, the router would not know to send it to your computer. UPnP lets UPnP-aware application programs automatically set up forwarding in the router.

Software running on the network to tell the router to forward expected incoming connections to the correct computer. Online messaging programs often require this. When the computer on the other end of the connection starts sending data, the router would not know to send it to your computer. UPnP lets UPnP-aware application programs automatically set up forwarding in the router.

![]() Other types of as-yet-undeveloped hardware devices to announce their presence on the network so that Windows can automatically take advantage of the services they provide.

Other types of as-yet-undeveloped hardware devices to announce their presence on the network so that Windows can automatically take advantage of the services they provide.

To use UPnP, you must enable the feature in your router. It’s usually disabled by default. If your router doesn’t currently support UPnP, you might have to download and install a firmware upgrade from the manufacturer. Most routers now do support UPnP.

Configuring the Rest of the Network

Whichever scheme you used, after you’ve set up the connection and router, configuring the rest of your LAN should be relatively easy. On each of your Windows 10, 8, or 8.1 computers that uses a wired Ethernet connection to the router, follow these steps:

1. At the Windows desktop, right-click the network icon in the notification area. Select Open Network and Sharing Center. At the left, select Change Adapter Settings. Right-click the computer’s Ethernet or Wireless network icon, depending on which you’re using and select Properties.

2. Select Internet Protocol Version 4 (TCP/IPv4), and then select Properties.

3. Check Obtain an IP Address Automatically and Obtain DNS Server Address Automatically. Then click OK.

4. Repeat steps 2 and 3 for Internet Protocol Version 6 (TCP/IPv6), but instead of selecting Internet Protocol Version 4 in step 2, select Internet Protocol Version 6. Click Close to close the dialog box.

5. When finished, you should be able to open a web browser and view a website.

(On versions of Windows other than Windows 10, 8, or 8.1, you will have to use different selections to get to your network adapter’s settings.)

That’s all you need to do to share your Internet connection. If your network will host servers that need to be reachable from the outside world, proceed with the next section.

Making Services Available

You might want to make some internal network services available to the outside world through your Internet connection. You would want to do this in these situations:

![]() You want to host a web server using Internet Information Services (IIS).

You want to host a web server using Internet Information Services (IIS).

![]() You want to enable incoming VPN access to your LAN so you can securely connect from home or afield.

You want to enable incoming VPN access to your LAN so you can securely connect from home or afield.

![]() You want to enable incoming Remote Desktop access to your computer.

You want to enable incoming Remote Desktop access to your computer.

![]() Caution

Caution

Make absolutely sure that Windows Firewall is turned on, to protect your network from hackers. For more information on network security, see Chapter 33.

If you have set up routed Internet service with multiple IP addresses, you don’t have to worry about this because your network connection is wide open and doesn’t use NAT. As long as the outside users know the IP address of the computer hosting your service—or its DNS name, if you have set up DNS service—you’re on the air already.

![]() Note

Note

If you’re interested in being able to reach your computer over the Internet using Remote Desktop, see Chapter 39, “Remote Desktop and Remote Access,” which is entirely devoted to the subject.

Otherwise, you have either Windows Firewall, NAT, or both in the way of incoming access. To make specific services accessible, configure Windows Firewall on the service hosting computer, and you must configure your router to forward incoming requests to that computer.

On the computer that is providing the service itself, you must tell Windows Firewall to allow incoming connections to the service by following these steps:

1. Go to the Start menu, and in the Search box, type firewall. Select Windows Firewall.

2. Click Advanced Settings. In the left pane, click Inbound Rules. Locate the service that this computer is providing, and find the line for the Private profile. If the service is listed with Yes in the Enabled column and Allow in the Action column, you can proceed to configure the computer that is sharing its Internet connection.

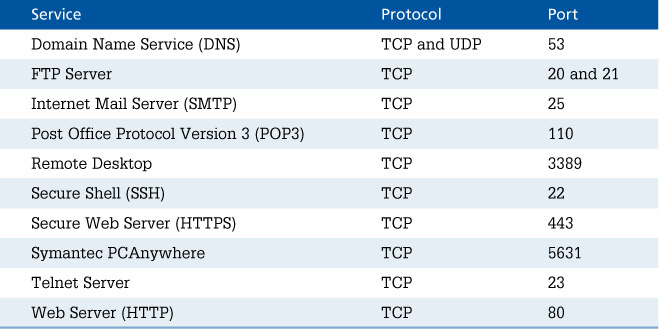

3. If the service isn’t already listed, click New Rule in the right pane. Click Port, click Next, select TCP or UDP, and enter the specific port number or port number range required by the service. Table 19.1 lists common services, port numbers, and protocols. (For the FTP and DNS services, you have to make two entries.) Alternatively, you could add a new rule and select Program, to enable all incoming connections to an application.

4. Click Next and click Allow the Connection.

5. Click Next and leave all three check boxes (Domain, Private, Public) checked.

6. Click Next. For the rule name, enter the name of the service you’re enabling, add an optional description, and click Finish.

Next, you must tell your router to forward incoming requests for each designated service to the computer that will handle them.

Some home/small office routers let you forward incoming Internet requests to a network computer by specifying the computer’s name. If yours permits this, you’re in luck because it means you can let the router assign IP addresses to your computer as it pleases. The router’s forwarding feature will always find the right service for each computer because it can find them by name.

Other routers require you to forward services by IP address, not by computer name. If like most networks yours is set up to have computers obtain their IP addresses automatically, your computers are moving targets, because their IP address could change from day to day, and the forwarding feature will likely send requests to the wrong address.

So, you must make special arrangements for assigning addresses to the computers on your LAN that you want to use to host services. On your router’s setup screens, make a note of the range of IP addresses that it will hand out to computers requesting automatic (DHCP) configuration. Most routers have a place to enter a starting IP address and a maximum number of addresses. For instance, the starting number might be 2, with a limit of 100 addresses. For each computer that will provide an outside service, pick a number between 2 and 254 that is not in the range of addresses handed out by the router, and use that as the last number in the computer’s IP address. We recommend using address 250 and working downward from there for any other computers that require a static address.

To configure the computer’s network address, follow the instructions under “Port Forwarding with a Router” in Chapter 39, with these changes:

![]() The material in Chapter 39 shows instructions for setting up access to the Remote Desktop service, using protocol TCP and port 3389. You can use the same procedure to set up access to your service, except substitute the protocol and port numbers for the service you’re enabling.

The material in Chapter 39 shows instructions for setting up access to the Remote Desktop service, using protocol TCP and port 3389. You can use the same procedure to set up access to your service, except substitute the protocol and port numbers for the service you’re enabling.

![]() Use a static IP address ending with .250 for the first computer you set up to receive incoming connections. Use .249 for the second computer, and work downward from there. Be sure to keep a list of the computers you assign static addresses to as well as the addresses you assign.

Use a static IP address ending with .250 for the first computer you set up to receive incoming connections. Use .249 for the second computer, and work downward from there. Be sure to keep a list of the computers you assign static addresses to as well as the addresses you assign.

For services that use TCP/UDP in unpredictable ways, you must use another approach to forwarding on your LAN. Some services, such as many text, voice, or video chat programs, communicate their private, internal IP address to the computer on the other end of the connection; when the other computer tries to send data to this private address, it fails. To use these services with a hardware router, you must enable UPnP, as described earlier in the chapter.

Other services use network protocols other than TCP and UDP, and most routers can’t be set up to forward them. Incoming Microsoft VPN connections fall into this category. Some routers have built-in support for Microsoft’s PPTP protocol. If yours has this support, your router’s manual will tell you how to forward VPN connections to a host computer.

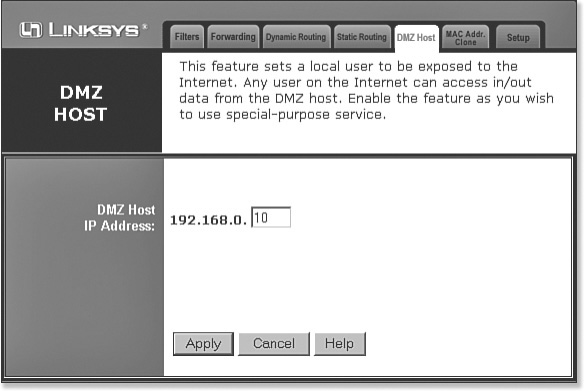

Otherwise, to support nonstandard services of this sort, you have to tell the router to forward all unrecognized incoming data to one designated computer. In effect, this exposes that computer to the Internet, so it’s a fairly significant security risk. In fact, most routers call this targeted computer a DMZ host, referring to the notorious Korean no-man’s-land called the Demilitarized Zone and the peculiar danger one faces standing in it.

To enable a DMZ host, you need to use a fixed IP address on the designated computer, as described in the preceding section. Use your router’s configuration screen to specify this selected IP address as the DMZ host. The configuration screen for my particular router is shown in Figure 19.5; yours might differ.

Figure 19.5 Enabling a DMZ host to receive all unrecognized incoming connection requests. This is an option of last resort if you can’t forward incoming connections any other way.

Now, designating a DMZ host means that this computer is fully exposed to the Internet, so you must protect it with a firewall of some sort. On this computer, you must set its network location to Public, and it can’t participate in file sharing or a homegroup.

You should also set up filtering in your router to block ports 137–139 and 445. Figure 19.6 shows how this is done on my Linksys router; your router might use a different method.