3. Your First Hour with Windows 10

The First Things to Do After Starting Windows 10

If you just installed Windows 10, or have just purchased a new computer that came with Windows 10 already installed, you’re probably itching to use it. This chapter is designed to help get you off to a good start. We’re going to take you and your computer on a guided tour of the new and unusual features of Windows 10, and walk you through making some important and useful settings. Here’s our itinerary:

![]() A quick tour of the important Windows 10 features

A quick tour of the important Windows 10 features

![]() Setting up user accounts

Setting up user accounts

![]() Personalizing system settings to make using Windows more comfortable and effective

Personalizing system settings to make using Windows more comfortable and effective

![]() Transferring information from your old computer

Transferring information from your old computer

![]() Logging off and shutting down

Logging off and shutting down

Our hope is that an hour or so invested in front of your computer following us through these topics will make you a happier Windows 10 user in the long run.

At the end of the chapter, we have some additional reference material. If you’re moving to Windows 10 from Windows XP, you will almost certainly want to read the final sections. If you have previously used Windows Vista, 7, 8, or 8.1, you might want to quickly scan the last sections just to know what’s there. The information might come in handy at some point in the future.

A Quick Tour of the Important Windows 10 Features

This section discusses some of the most important features and the most significant differences between Windows 10 and its predecessors. It is best if you read this while seated in front of your computer and follow along. That way, when you run into these features and topics later in this book and in your work with Windows, you’ll already have “been there, done that” at least once. We’ll start with the Lock screen, which you’ll see after you finish installing Windows 10 or when you turn on a new Windows 10 computer for the first time.

![]() Note

Note

If you’re using Windows in a corporate setting and your computer was set up for you, some of the steps in this chapter won’t be necessary, and they might not even be available to you. Don’t worry—you can skip over any parts of this chapter that have already been taken care of, don’t work, or don’t interest you.

If you used Windows 8 or 8.1 previously and have purchased a new device or upgraded to Windows 10, you might also want to refer to “What Changed Between Windows 10 and Windows 8 and 8.1” on page 27.

![]() Tip

Tip

If your device has a touch screen, here’s something you’ll want to remember: If you touch something on the screen and hold your finger on it without moving it for a second or two, until the circle around your finger turns into a square, and then release your touch, this does the same thing as right-clicking with a mouse. When you release your finger, the right-click action will occur; for example, a menu will pop up. This works anywhere a right-click would work.

The Lock and Sign In Screens

When Windows starts, you see the Lock screen, which displays just a picture, the time, and the date. Type any key, click anywhere on the screen with your mouse or, if you have a touchscreen, touch it and slide your finger upward. (This gesture is called a swipe.) The Lock screen slides up and out of view to reveal the Sign In screen, shown in Figure 3.1, which has an icon (tile) in the lower-left side of the screen for each person (user, in computer parlance) who has been authorized to use the computer.

At the bottom-right corner of the screen are icons that let you enable the computer’s Internet connection, activate accessibility aids, and power off the computer without having to sign in first. There might also be an icon that lets you switch languages and keyboard layouts if your computer was set up for multilingual input.

Touch or click your account’s tile to sign in. The last account used is preselected.

If your account has a password associated with it, by default, Windows will prompt you for a password, as in previous versions. There are other ways to sign in, using setup options we describe shortly. They are as listed here:

![]() Password—Enter your password and press Enter, or click or touch the right-arrow button to complete the sign in process.

Password—Enter your password and press Enter, or click or touch the right-arrow button to complete the sign in process.

![]() Picture Password—Make your preset three gestures on the sign-in picture. To make a gesture, touch a point on the picture, drag your finger or the mouse pointer to another point, and release.

Picture Password—Make your preset three gestures on the sign-in picture. To make a gesture, touch a point on the picture, drag your finger or the mouse pointer to another point, and release.

If you just purchased a new computer, the first screen you see might be from the tail end of the installation process described in Chapter 2, “Installing or Upgrading to Windows 10.” Your computer’s manufacturer set it up this way so that you could choose settings such as your local time zone and keyboard type. If you do see something other than the Lock or Sign In screens, scan back through Chapter 2. If you recognize the screen you see in one of that chapter’s illustrations, carry on from there.

If Windows jumps right up to the desktop and skips the Sign In screen, your computer’s manufacturer set up Windows not to require a username or password. In this case, skip to the following section in this chapter, where we show you how to set up a user account.

![]() PIN—Type your four-digit PIN code using your keyboard or the touchscreen keyboard.

PIN—Type your four-digit PIN code using your keyboard or the touchscreen keyboard.

![]() Biometric—If your device includes a fingerprint scanner, or a camera that has infrared capabilities, you can use these as sign-in devices. The device’s manufacturer will provide instructions for these methods.

Biometric—If your device includes a fingerprint scanner, or a camera that has infrared capabilities, you can use these as sign-in devices. The device’s manufacturer will provide instructions for these methods.

The first time you sign in (and only the first time), it might take a few minutes for Windows to prepare your user profile, the set of folders and files that holds your personal documents, email, pictures, preference settings, and so on.

If you have difficulty hearing or seeing the Windows screen, use the Ease of Access icon at the lower-left corner of the Sign In screen to display a list of accessibility options. These include Narrator, which reads the screen aloud; Magnifier, which enlarges the display; and High Contrast, which makes menu and icon text stand out more clearly from the background. You can select any of these items that will make Windows easier for you to use. You can press the left Alt key, the left Shift key, and the PrtScr key together to toggle High Contrast.

After you’re signed in, you can use the Windows Logo+U keyboard shortcut to open the Ease of Access Center anytime.

The Start Menu

When you’ve signed in, Windows displays a familiar Windows desktop. If you click or touch the Start button (the Windows logo button) in the lower-left corner, you’ll see the new style Start menu, shown in Figure 3.2. We talk more about the Start menu in Chapter 4, “Using the Windows 10 Interface.” Here, we just want to point out a few things, and you might want to follow along with your copy of Windows as we go:

![]() You can bring up the Start menu at any time by pressing the Windows Logo key, or by touching or clicking the Start button.

You can bring up the Start menu at any time by pressing the Windows Logo key, or by touching or clicking the Start button.

![]() The large icons on the Start menu are called tiles. Some of them, such as the Calendar, News, and Finance apps, display live, updated data from the Internet.

The large icons on the Start menu are called tiles. Some of them, such as the Calendar, News, and Finance apps, display live, updated data from the Internet.

![]() You can scroll the menu contents up and down if it contains more tiles than fit at once. You can move it by using the mouse (there is a scrollbar at the right edge) or your finger, if you have a touchscreen. Just touch the scroll bar and slide it up or down.

You can scroll the menu contents up and down if it contains more tiles than fit at once. You can move it by using the mouse (there is a scrollbar at the right edge) or your finger, if you have a touchscreen. Just touch the scroll bar and slide it up or down.

![]() Personalizing the Start menu is the key to making Windows 10 easy to use. Pin your favorite applications (apps) and folders to the Start menu. Drag tiles around so that the apps you use most often appear on the first page of the menu. Right-click or touch and hold tiles to make them larger or smaller. You can even create groups of apps and assign names to the groups.

Personalizing the Start menu is the key to making Windows 10 easy to use. Pin your favorite applications (apps) and folders to the Start menu. Drag tiles around so that the apps you use most often appear on the first page of the menu. Right-click or touch and hold tiles to make them larger or smaller. You can even create groups of apps and assign names to the groups.

![]() Click or touch All Apps to view an extended, alphabetical app list. (This is the equivalent of selecting All Programs on the Start menu in previous versions of Windows.)

Click or touch All Apps to view an extended, alphabetical app list. (This is the equivalent of selecting All Programs on the Start menu in previous versions of Windows.)

![]() For more information, see “Customizing the Start Menu,” p. 120.

For more information, see “Customizing the Start Menu,” p. 120.

Modern Apps

The Start menu holds icons for standard Windows desktop applications, such as Microsoft Word and the old familiar Notepad, and also new Modern apps, which have a simplified, clean graphical user interface without the traditional menu. This new graphical style has also been referred to as Metro and Windows-8 Style, but the official name is now Modern. In this book, when we refer to a Modern app, we’re referring to this new, simplified full-screen graphical look.

To see how this looks, open the Start menu and touch or click the Weather tile. If a prompt asks whether it’s okay to use your location, click Allow. You might also be asked to choose between Fahrenheit and Celsius temperatures and to enter your city name. You should end up with a window like that shown in Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3 Modern apps have a standard Windows title bar. Apps vary in their design, but they usually have common graphic elements such as the “hamburger” menu icon and the “gear” settings icon.

Notice that Modern apps have a normal Windows title bar across the top, with the usual Minimize, Maximize, and Close buttons at the far right. In Windows 10, they are not distinct square buttons, just symbols, but they work just as they have in all previous versions of Windows.

Modern apps have no standard menu bar (File, Print, Edit) under the title bar, but most Modern apps have one or more icons that perform these functions. The most common icon is the “hamburger” icon, which displays a menu of commands and options. It’s typically in the upper-left corner of the app’s window. There might be a gear-shaped icon that lets you change settings and sometimes a magnifying glass icon that performs a search function. You can find out what these icons do by hovering your mouse over them, or just clicking or touching them. Some apps might have a feedback icon that lets you tell its developers what you like or don’t like about the app’s design and function. This icon is usually a smiley face.

To get to an app’s commands, touch or click its hamburger icon. For apps that were designed for Windows 8, the hamburger icon appears in the title bar. In these Windows 8-style apps, you can press Windows Logo+Z as a shortcut to the App Commands menu panel, which slides into the top and/or bottom part of the window.

![]() To learn more about using and managing Modern apps, see “Working with Running Apps,” p. 111.

To learn more about using and managing Modern apps, see “Working with Running Apps,” p. 111.

Close the Weather app by touching or clicking the X in its upper-right corner.

The Touch Tour

If your computer has a touch interface, you can make several gestures with one or two fingers to make quick work of navigating through Windows. (Yes, we’ve all been making certain finger gestures at our computers for years, but this is different.)

In “Navigating Windows 10 with a Touch Interface” in Chapter 4, we list the touch gestures in detail. Here, we just want to show you some basic navigation moves. Follow these steps:

1. Open the Start menu, touch the Calendar tile, and keep your finger on it. Drag it to another location on the menu and release it. This is dragging. Drag the icon back where it came from.

2. Tap the Maps tile. This is the same as a mouse click.

3. If the app says it needs to access your location, touch Allow.

4. When a map is displayed, touch one finger to the screen and drag the map side to side. Touch two fingers to the map, say, your thumb and forefinger, a few inches apart. Then squeeze them together. The map should zoom out. Slide your fingers apart, and the map should zoom in.

5. Touch one finger just outside the far-right edge of the screen and quickly drag it back toward the middle about an inch or two, like you were trying to flip the page of a book. This is a swipe, and it should bring up the Action Center, a very useful panel that contains notifications and a bunch of handy control buttons. You can swipe it away using the reverse of that gesture: swipe from the middle of the App Center window to the right edge of the screen.

6. Go back to the Start menu and touch the Calendar app.

7. Swipe your finger from the left edge of the screen toward the center (just an inch or two), again as if you were flipping the pages of a book. This should let you easily select an app to bring up to the foreground.

8. Touch your finger to the Start button and hold it a couple of seconds, until the touch indicator circle changes shape. Release your finger, and a menu will pop up. The touch-and-hold gesture is the same as right-clicking with a mouse. (Take a quick look at this menu while you’re here. It’s called the Power User menu and leads to almost every Windows management tool.)

If you practice these gestures a few times, you’ll quickly get a feel for using the touch interface.

Throughout this book, if we use the terms “click” or “right-click,” and you are using a touchscreen without a keyboard, remember that a touch is the same as a click, and a touch and hold is the same as a right-click.

![]() To read more about using a touch screen, see “Navigating Windows 10 with a Touch Interface,” p. 109.

To read more about using a touch screen, see “Navigating Windows 10 with a Touch Interface,” p. 109.

Important Keyboard Shortcuts

If you’re not using a touchscreen, you’ll find it much easier to use Windows 10 if you memorize at least a few keyboard shortcuts. These are the most important to learn:

If you memorize just these shortcuts, you’ll be way ahead of the game!

![]() For more useful keyboard shortcuts, see “Navigating Windows 10 with a Keyboard,” p. 107.

For more useful keyboard shortcuts, see “Navigating Windows 10 with a Keyboard,” p. 107.

There are also useful keyboard shortcuts to switch between apps. Alt+Tab cycles through traditional desktop applications and Modern apps.

Tablet Mode

The biggest criticism of Windows 8 was that the Start menu (called the Start Screen in Windows 8) and Modern apps occupied the entire screen. The Windows desktop and desktop applications lived in another world, and users found the way that Windows 8 flipped back and forth between them to be jarring.

On tablets, this behavior wasn’t quite so annoying, because on a device with a smaller screen, you usually want an app to fill as much of the screen as possible.

In Windows 10, you get to choose how you want Windows 10 to behave, on both desktops and tablets, by enabling or disabling Tablet mode.

When Tablet mode is off, both Modern and desktop apps can be resized and moved around as on older versions of Windows.

If you have a Windows 10 computer in a tablet format, review this section carefully, following along on your device as you read. When Tablet mode is turned on, the following changes take effect to get the most out of limited screen real estate:

![]() The Start menu hides the panel of icons that usually appear at the left side: Most Used, File Explorer, Settings, and so on, as you can see in Figure 3.4. Touch the hamburger icon in the upper-left corner to display them. Tablet mode can be very frustrating until you learn this!

The Start menu hides the panel of icons that usually appear at the left side: Most Used, File Explorer, Settings, and so on, as you can see in Figure 3.4. Touch the hamburger icon in the upper-left corner to display them. Tablet mode can be very frustrating until you learn this!

![]() The Start menu and all open apps are automatically maximized to fill the screen.

The Start menu and all open apps are automatically maximized to fill the screen.

![]() By default, the taskbar doesn’t show icons for running apps. Instead, you switch between apps by swiping in from the left edge of the screen. We prefer to have the taskbar icons appear. We’ll tell you to have them show up shortly.

By default, the taskbar doesn’t show icons for running apps. Instead, you switch between apps by swiping in from the left edge of the screen. We prefer to have the taskbar icons appear. We’ll tell you to have them show up shortly.

![]() The taskbar’s search box collapses to an hourglass icon, or a circle if you’ve enabled Cortana, as discussed later in the chapter. Touch it to perform a search.

The taskbar’s search box collapses to an hourglass icon, or a circle if you’ve enabled Cortana, as discussed later in the chapter. Touch it to perform a search.

![]() Tip

Tip

Throughout this book, we frequently tell you to click Start, then Settings. If you are using a touchscreen with Tablet mode turned on, mentally translate that to “Touch Start, Hamburger, Settings.”

![]() Modern apps don’t display a close box (X) in their upper-right corner. To close an app, just switch to another app; or, drag your finger from the top center of the screen down a short distance toward the middle to make the title bar and close box appear; or, drag your finger down the middle of the screen from the very top to the very bottom. You might want to practice these moves now, using the Weather app or another Modern app.

Modern apps don’t display a close box (X) in their upper-right corner. To close an app, just switch to another app; or, drag your finger from the top center of the screen down a short distance toward the middle to make the title bar and close box appear; or, drag your finger down the middle of the screen from the very top to the very bottom. You might want to practice these moves now, using the Weather app or another Modern app.

If you connect or remove a keyboard and mouse from a tablet, or you dock or undock a hybrid tablet/laptop, Windows can automatically switch Tablet mode on or off for you. This is called the Continuum feature.

To configure Tablet mode, touch or click the Start button. If the Settings icon doesn’t appear, touch the Hamburger icon. Then, select Settings, System, Tablet Mode. You might want to go there now and turn off the setting Hide App Icons in the Taskbar When in Tablet Mode. This lets the taskbar show icons for active Modern apps.

To have Windows switch automatically between Desktop mode and Tablet mode when you attach or detach a keyboard, under When This Device Automatically Switches..., select Don’t Ask Me and Always Switch, or Ask Me Before Switching, as you prefer. Choose Don’t Ask Me and Don’t Switch to prevent automatic switching.

There are two ways to turn Tablet mode on or off manually: You can select Start, Settings, Tablet Mode and use the On/Off switch. But this is quicker: Swipe your finger in from the right edge of the screen to display the Action Center, then use the Tablet Mode button at the bottom-right part of the screen. The Action Center panel also has a handy Rotation Lock button to prevent your screen from flipping around as you turn your tablet.

Windows Explorer Is Now Called File Explorer

To continue our tour, let’s take a quick look at Windows Explorer... oops, we mean File Explorer. It has a new name (as of Windows 8) and a ribbon bar in place of a menu. By default, File Explorer is pinned to the taskbar. To open File Explorer, touch or click the taskbar icon that looks like a manila file folder. If there is no File Explorer icon in the taskbar, touch or click Start, find File Explorer at the left side, and right-click it, or touch and hold your finger on it until a pop-up menu appears. Select Pin to Taskbar. Now you can open File Explorer from the taskbar.

File Explorer will open in the Quick Access view, which shows your most recently used files and folders, and files and folders that you’ve pinned for Quick Access. Click or touch This PC in the left pane to see the view shown in Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5 File Explorer sports a new name and a new ribbon interface. The list of actions shown in the ribbon changes when you select a tab and when you select items in the Content pane.

In the left pane, which is called the Navigation pane, you can select the major categories Quick Access, This PC, Homegroup (if one is set up on your network—more on that in Chapter 18, “Creating a Windows Network”), and Network. If you are signed in using a Microsoft account, OneDrive will also appear; it’s the folder that is synced with your account’s online storage.

Collectively, all of these various categories display what the old separate Favorites, My Documents, [My] Computer, and other links displayed in earlier versions of Windows.

As you select items in the right pane, which we call the Content pane, the ribbon bar changes to show actions that you can perform on the selected object(s). Be aware of this: The ribbon does not respond to and act on items you select in the left pane, just the right pane.

Did you like the old Windows 7 and 8 Libraries feature, which collected the files in several folders and displayed them together? Libraries still exist in Windows 10, but they’re turned off by default. To show them, select View (along the top of the window), Options, Change Folder and Search Options; check Show Libraries under Navigation Pane in the General tab, and then click OK.

Cortana

The desktop’s taskbar has a full-time resident search tool. It appears either as a magnifying glass icon or as the rectangular box shown in Figure 3.3. As initially installed, this tool searches for text in Settings and Control Panel entries, for the names of files in local (internal and external drive) and online (OneDrive) storage, and uses Bing to search the Web, presenting the combined results from all of these locations. To give it a try, click the Search area now. It should say Search the Web and Windows. Type weather and the first result to appear should be the Weather app installed with Windows, followed by web results, which might even include the local weather for your location if Bing was smart enough to figure that out.

![]() To customize the search tool, see “Customizing the Start Menu,” p. 120.

To customize the search tool, see “Customizing the Start Menu,” p. 120.

You can also choose to enable Cortana, Microsoft’s new search tool that performs something like Apple’s Siri. It tries to understand questions and commands in human language such as “What will the weather be in Boise, Idaho tomorrow?” or “Set an alarm for 8:30 tomorrow morning.” It not only searches the Web but also interacts with your calendar, contacts list, and other information it learns about you, such as the places you visit frequently, so that it can provide much more personally tailored answers and service. If you have a microphone attached, you can speak your commands and questions. You can even tell Cortana to “listen” all the time, so all you have to do is say “Hey, Cortana” and ask your question without touching a thing.

To give Cortana a try, click in the taskbar’s Search box, and then click the Settings (gear) icon on the left side of the panel that pops up. Turn on the switch under Cortana. If your device has a microphone installed, farther down there might be a switch titled Hey Cortana. If it’s there, turn it on. Under Tracking, turn off the switch unless you want Cortana to read your email and text messages to learn more about you, what you like, and what you’re doing these days. (Seriously! It’s like having your own personal stalker.) The first time you activate Cortana, a panel will appear asking what you’d like to be called. You can enter your first name or a nickname here if you want. (“Oh Master” is especially nice.)

Now, with Cortana turned on, the taskbar’s Search box will have a circle icon in it. Click it and type what time is it in Boise, or, if you have a microphone, say “Hey Cortana,” wait for the Search box to say “Listening...” and then ask “What time is it in Boise?” Or try “tell me a joke.”

![]() Note

Note

As I was writing this, from somewhere on my cluttered desk a disembodied computer voice said, “Sorry, I missed that.” Surprised, I exclaimed, “Who just said that? Siri? Cortana?” But nobody fessed up.

I think the future is going to be a lot like that.

Cortana might be very helpful, and over time as its software is improved and as it learns more about you, it will get even better. But you do sacrifice some privacy, as everything you ask of Cortana will almost certainly get recorded in Microsoft’s data centers somewhere. It’s your call. If you don’t want to continue to use Cortana, click in the Search box, select the Settings icon, and turn off Cortana.

![]() To read more about Cortana, see “Searching with Cortana,” p. 118.

To read more about Cortana, see “Searching with Cortana,” p. 118.

Search Before You Look

Whether you use Cortana or not, here’s one of the most important tips we can give you for Windows 10: Although there are usually many ways to get to the same thing in Windows, the fastest way is to let Windows find it for you.

Click in the taskbar’s Search box and just type away. If your computer doesn’t have a keyboard, touch the Search box in the taskbar, and then type using the screen’s Touch keyboard. Simply type the first few letters or words associated with the Control Panel item, app, setting, or file that you’re looking for. If you have Cortana enabled and have a microphone attached, you can just say “Hey, Cortana” and say what you’re looking for.

Windows can find and list apps, files, settings, or Control Panel items much faster than you could ever get to them by poking around with the mouse or by scrolling through the Start menu.

The same applies to searches within the Settings, Control Panel, and any File Explorer screens. It’s usually much faster and easier to type a few letters of the name of what you’re looking for than to hunt, click, and dig using the mouse. Don’t remember what the Control Panel app is called? No worries. Just type a related word or words. Chances are that the item you want will appear in the search results under Settings.

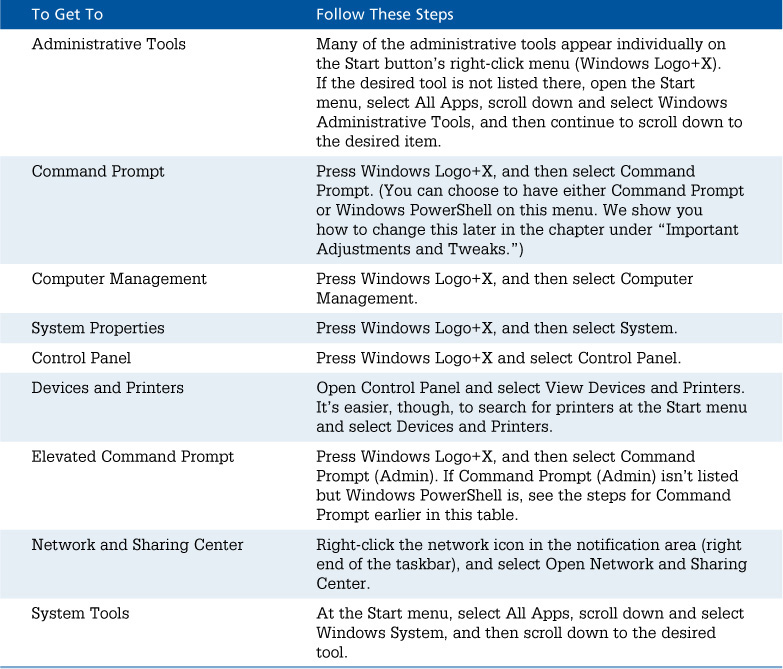

Getting to the Management Tools

It might seem difficult at first to get to the tools you need to use to manage Windows. Remember, you can simply search for any desired management tool or setting by typing its name or a word that describes it in the taskbar’s Search box. This will usually do the trick.

![]() Tip

Tip

On Windows XP through 7, you right-clicked My Computer to get to the Windows management tools. On Windows 10, right-click or touch and hold the Start button. This displays a big list of tools. To get to the remaining settings, click the Action Center icon at the right end of the taskbar, or swipe in from the right edge of the screen, and then click All Settings.

Memorize these two paths, and you’ll save yourself hours of poking around looking for things!

The best thing to know is that you can pop up a menu of management tools by right-clicking the Start button or by pressing Windows Logo+X. Without a keyboard, touch and hold the Start button until the pop-up Power User menu appears.

From there, you can instantly open many Control Panel sections, Device Manager, Computer Management, the Command Prompt, Task Manager, and more. Try it now: Right-click or touch and hold the Start button, and see what’s there.

Table 3.1 lists quick ways to get to many management tools using keyboard shortcuts. If your device doesn’t have a keyboard, where the instructions say press Windows Logo+X, instead touch and hold the Start button until a pop-up menu appears.

If you need to run a tool with elevated privileges, right-click or touch and hold the item in the menu or search results, and then select Run as Administrator.

![]() Note

Note

The Back button is located all over the place in Windows 10. It can come in handy, so make a mental note to look for it as you use various Control Panel options, File Explorer, setup wizards, and so on.

By the way, in the Control Panel, the View By drop-down item lets you instantly switch back and forth between the Category view and an icon view that resembles the Windows 9x Control Panel. In this book, our instructions refer to the Category view unless we state otherwise.

If you have trouble finding a setting, check this book’s index, which should lead you to instructions for finding the correct links in the Control Panel or elsewhere. You can also use the Search box at the top of the Control Panel window.

Setting Up User Accounts

On a computer that’s joined to a corporate Windows domain network, the network servers take care of authorizing each user, and accounts are created by network managers.

On home and small office computers, it’s best to set up a separate account for each person who will use the computer. Having separate user accounts keeps everyone’s stuff separate: email, online purchasing, preferences and settings, documents, and so on. Although it’s certainly possible for everyone to share one account, having separate accounts often turns out to be more convenient than sharing.

Microsoft Versus Local Accounts

On a computer that has Internet access, you can create two types of user accounts: Microsoft accounts and local accounts. A local account is what we had in previous versions of Windows. You can specify an account (sign in) name and password. Information about each account stays on the computer. If you set up accounts for yourself on two different computers, your password on the two machines would not necessarily be the same, your individual preferences would have to be set up separately on both computers, and so on.

If you use a Microsoft account (formerly called a Windows Live account) to sign in to Windows 8 or 10, Windows uses Microsoft’s online services to securely back up certain information from your account to Microsoft’s servers “in the cloud,” which means “in some big data center somewhere—we don’t really know where, but it works.” You use your Microsoft account email address and password to sign in to Windows. If you use the same Microsoft account to sign in to another Windows 8 or 10 computer, your information follows you—your password, preferences, purchased apps, and so on. It’s pretty spiffy. (Documents, music, and so on don’t follow you automatically, but you can use OneDrive or other online data services for that.)

For the online account scheme to work, the computer must have a working Internet connection when you sign in for the first time so that Windows can check your password. Also, it’s best if the computer has an always-on Internet connection so that your information can be backed up as you work. If the Internet connection goes down later, you can still sign in. Windows remembers your last-used password.

This is important: The first time you sign in to any given computer with your Microsoft account, you must verify to Microsoft that you are who you say you are. You must perform the verification step before any of your files, apps, or other content will be pulled in from your Microsoft account’s online storage to the computer. If Windows doesn’t prompt you to verify your account shortly after you sign in for the first time, click the Action Center icon at the right end of the taskbar. The icon looks like the square cartoon “voice balloon” shown here: ![]() In the Action Center panel, click or touch Verify Your Identity on this PC, then follow the instructions to receive a code by text message or email. Enter the code when you’re asked for it, and then your computer’s account will be fully linked up with your online account.

In the Action Center panel, click or touch Verify Your Identity on this PC, then follow the instructions to receive a code by text message or email. Enter the code when you’re asked for it, and then your computer’s account will be fully linked up with your online account.

![]() Tip

Tip

If you purchased a computer with Windows 10 preinstalled, the manufacturer might have set up Windows to skip the sign-in process entirely. There actually is a user account set up for you, and when you start Windows, it automatically signs in to that one account.

If you expect to have other people use your computer, go ahead and create more user accounts now. We show you how to make the Sign In screen work later in the chapter, in the section “Just One User?”

You can change any account from a Microsoft account to a local account, and vice versa. If you switch to a local account, settings you change and purchases you make from that point forward won’t follow you from computer to computer. You can switch back to an online account anytime.

In addition, you can choose between Administrator and Standard User types. An Administrator can change any setting as well as view any file on the computer (even someone else’s). A Standard User can’t change Windows settings that involve networking or security, and can view other people’s files only if they’ve chosen to share them.

The first account set up on your computer during installation and finalization is always an Administrator account. At this point on our tour, let’s add user accounts for other people who will be using your computer.

Create New Accounts

Open the Start menu by clicking or touching the Start button in the bottom-left corner of the screen. Then, starting at the bottom-left side of the Start menu, select Settings, then Accounts. If Settings doesn’t appear in the Start menu, select All Apps, scroll down to the letter S, and select Settings.

You should see information about your own account in the right pane, as shown in Figure 3.6. You can scroll the window down to get to other items that let you use your device’s camera to take your picture, link to additional Microsoft accounts, and so on.

If you want to create a new Microsoft account so that someone else can use your computer, either she must have already set up her account online at login.live.com, or she should be present to set up a new account while you’re adding her to your computer, because she will have to create a password and enter personal information.

![]() Tip

Tip

If you want maximum protection against viruses and other malware, reserve that first Administrator account for management work only, and then create a standard user account for yourself for day-to-day use. This makes it harder to get tricked into letting bad software run without noticing.

Windows 10 includes a family-computing feature that lets a family’s adults manage, limit, and supervise their children’s computer use. This feature works only with Microsoft online accounts so that the managing (parent) accounts can restrict and monitor the use of the managed (child) accounts on any devices they have. This feature includes receiving activity reports that show what the managed (child) accounts were looking up on various search engines, websites they visited, how long they were on the computer, and which games and apps they used.

If you don’t need to use this supervisory feature, you can set up regular Microsoft or local accounts for other users.

To set up family-centered user accounts with restricted and monitored access for children, select Add a Family Member, then select Add a Child or Add an Adult. Otherwise, to add another user without making him part of a family group, and select Add Someone Else to This PC.

Then, you must choose to create a Microsoft (online) or local (offline) account. Remember, a local account gives less information about your computer use to Microsoft but will not automatically sync up preferences and settings between the user’s different computers.

To set up a Microsoft account, use one of the following options:

![]() If the person has already created a Microsoft account online, enter his Microsoft Account email address.

If the person has already created a Microsoft account online, enter his Microsoft Account email address.

![]() If the person has an email address already but hasn’t set up a Microsoft account yet, type in his email address and click Next. Follow the series of prompts as they appear. At the end, select Finish to create the Microsoft account.

If the person has an email address already but hasn’t set up a Microsoft account yet, type in his email address and click Next. Follow the series of prompts as they appear. At the end, select Finish to create the Microsoft account.

![]() If the person doesn’t have an email address, you can create one by clicking The Person I Want to Invite Doesn’t Have an Email Address and follow the prompts. This will let you create a new email address on one of Microsoft’s free online email services at the same time you set up the online account.

If the person doesn’t have an email address, you can create one by clicking The Person I Want to Invite Doesn’t Have an Email Address and follow the prompts. This will let you create a new email address on one of Microsoft’s free online email services at the same time you set up the online account.

When setting up a Microsoft account, be sure to provide at least one alternative email address, and if possible a mobile phone number that can receive text messages. Microsoft needs at least one of these to validate that the user really wants an account on your computer, and it also helps recover from a forgotten password.

The first time the new user signs in on your computer, he or she should immediately perform the validation step discussed previously under “Microsoft Versus Local Accounts.”

If you want to create a local account and not use Microsoft’s online account system, select The Person I Want to Add Doesn’t Have an Email Account, Add a User Without a Microsoft Account. Enter a username consisting of letters and, if desired, numbers. Choose a password and enter it twice as indicated. Enter a hint that will remind the user what his password is but won’t give a clue to anyone else. (This can be hard to come up with!) Click Next and then Finish.

![]() Tip

Tip

A Microsoft account user actually has a local user account on the computer, and Windows checks online to update the password and settings. The account is given a goofy name along the lines of brian_000. If you want your computer’s local accounts and user profile folders to have predictable, useful names, create accounts as local accounts first. Then have the users sign in and change them to Microsoft accounts.

If you’ve elected to set up accounts using the Family structure—if you designated users as adults or children—the adult users can manage and monitor what the child users can do and have done by visiting account.microsoft.com/family. Alternatively, click Start, Settings, Accounts, Family & Other Users, Manage Family Settings Online.

Initially, all new users are created as Standard Users. If you want them to be Administrators, under Add Someone Else To This PC, select the icon for the newly created account, select Change Account Type, in the drop-down list change the Account Type to Administrator, and then click OK.

Change Account Settings

To change the settings shown in Figure 3.6 for your own account, use the Accounts panel described in the preceding section. You can do the following:

![]() Select Your Account to change between a local and Microsoft account. Then select Sign In with a Local Account Instead to switch from an online account to a local account. Use Sign In with a Microsoft Account Instead to go from local to online.

Select Your Account to change between a local and Microsoft account. Then select Sign In with a Local Account Instead to switch from an online account to a local account. Use Sign In with a Microsoft Account Instead to go from local to online.

![]() Select Sign-In Options to change your password, create a picture password, or set a PIN.

Select Sign-In Options to change your password, create a picture password, or set a PIN.

A picture password lets you select a picture instead of a password to sign in. You draw three lines on the picture with your mouse or fingertip, gestures that only you know.

![]() Note

Note

Passwords to Wi-Fi networks to which you connect are also saved online, so be aware that you’re giving government agencies the key to your Wi-Fi networks too. It’s only somewhat comforting to know that they can easily get into your Wi-Fi networks without being handed this information, so letting Microsoft sync it isn’t making things any worse.

A PIN lets you use a four-digit number instead of a password to sign in. (This PIN works only at the Sign In screen, not over the network.)

![]() Select Work Access to access resources, apps, settings, and network connections provided by your organization’s network managers. If your organization uses this feature, they will provide you with detailed instructions for connecting to and using their resources.

Select Work Access to access resources, apps, settings, and network connections provided by your organization’s network managers. If your organization uses this feature, they will provide you with detailed instructions for connecting to and using their resources.

![]() Select Sync Your Settings to change what kind of information gets uploaded and associated with your Microsoft account.

Select Sync Your Settings to change what kind of information gets uploaded and associated with your Microsoft account.

Two settings on the Sync Your Settings panel that have significant privacy implications are Web Browser Settings and Passwords. If Web Browser Settings and Passwords are turned on, Windows may upload to Microsoft’s servers the names of websites you visit and the passwords you use to sign in to them. You can be assured that in the United States at the very least, this information is available to government agencies upon subpoena without any notification to you and maybe even without a judge’s warrant. You also might wonder what happens if Microsoft’s servers get hacked by criminals or governments.

![]() Tip

Tip

If you are in a home or small office environment, have more than one computer, and plan on setting up a local area network, we suggest you read about the Homegroup feature in Chapter 18. It really simplifies file sharing on Windows. If you don’t want to use it, though, but you do want to share files and printers, create local accounts for every one of your users on each of your computers using the same name and same password for each person on each computer. This makes it possible for anyone to use any computer, and it makes it easier for you to manage security on your network.

At this point on our tour of Windows 10, we recommend that you take a moment to add a user account for each person who will be using your computer. Definitely set a password on each Administrator account. We recommend that you set a password on each standard user account as well.

After you add your user accounts, continue to the next section.

Before You Forget Your Password

If you use a Microsoft (online) account, as discussed in the preceding section, and you forget your password, you can go online to reset your password and regain access to your computer accounts—as long as you can get to your mobile phone or one of the email accounts you linked to your Microsoft account, and as long as your computer has Internet access.

If you use a local account and forget your account’s password, you could be in serious trouble. On a corporate domain network, you can ask your network administrator to save you. However, on a home computer or in a small office, forgetting your password is very serious: You can use another Administrator account to change the password on your own account, but you will lose access to any files that you encrypted and to passwords stored for automatic use on websites. (Do you even remember them all?) And if you can’t remember the password to any Administrator account, you’ll really be stuck. You’ll most likely have to reinstall Windows and all your applications, and you’ll be very unhappy.

There is something you can do to prevent this disaster from happening to you. You can create a password reset disk right now and put it away in a safe place. A password reset disk is a removable thumb drive or other type of removable, writable disk linked to your account and lets you sign in using data physically stored on the disk. It’s like a physical key to your computer. Even if you later change your account’s password between making the disk and forgetting the password, the reset disk will still work to unlock your account.

![]() Caution

Caution

A password reset disk, or rather the file userkey.psw that’s on it, is as good as your password for gaining access to your computer, so store the reset disk in a safe, secure place. By “secure,” we mean something like a locked drawer, filing cabinet, or safe deposit box.

So, if you use a local (offline) account, make a password reset disk now! Here’s how. You need a removable USB thumb drive, or some other such removable medium. Follow these steps:

1. Connect the removable storage device to your computer.

2. In the taskbar’s search box, type password reset. Then select Create a Password Reset Disk. (If nothing happens, sign out, sign back in, and try again. My experience has been that the wizard opens reliably only if you insert the removable drive while signed in, sign out, sign back in, and then try Create a Password Reset Disk again.)

3. When the wizard appears, click Next.

4. If necessary, select a removable drive from the list and click Next.

5. Enter your current password and click Next.

6. Follow the wizard’s instructions. When the wizard finishes writing data, click Next and then click Finish.

The disk will now contain a file called userkey.psw, which is the key to your account. (You can copy this file to another medium, if you want.) Remove the disk, label it so that you’ll remember what it is, and store it in a safe place.

![]() Note

Note

Each local user should create her own password reset disk. In theory, an Administrator user could always reset any other user’s password, but that user would then lose her encrypted files and stored passwords. It’s better to have a separate password reset disk for every local user account. But if not every local account on your computer, at least one Administrator account.

You don’t have to re-create the disk if you change your password in the future. The disk will still work regardless of your password at the time. However, a password disk works only to get into the account that created it, so each user should create one.

If you forget your password and can’t sign in, see “After You Forget Your Password,” toward the end of this chapter.

Just One User?

If you are the only person who is going to use your computer, there is a setting you can use so that Windows starts up and goes directly to your desktop without asking you to sign in. You might find that your computer does this anyway; some computer manufacturers turn on this setting before they ship the computer to you. Technically, a password is still used; it’s just entered for you automatically.

We recommend that you don’t use this automatic sign-in option. Without a password, your computer or your Internet connection could be abused by someone without your even knowing it. Still, in some situations it’s reasonable to change this setting. For example, if your computer manufacturer set up your computer this way, you can disable it. Or you might want to use the feature in a computer that’s used in a public place or in an industrial control setting. To change the startup setting, follow these steps:

1. Press Windows Logo+R, type control userpasswords2, and press Enter.

2. To require a sign in, check Users Must Enter a User Name and Password to Use This Computer, and then click OK.

Alternatively, to make Windows sign in automatically, uncheck Users Must Enter a User Name and Password to Use This Computer, and click OK. Then type the username and password of the account you want to have signed in automatically, and click OK.

The change takes effect the next time Windows starts.

Downloading Critical Updates

The next thing to do is update Windows with the latest and greatest updates from Microsoft. Open the Start menu and select Settings. (If Settings does not appear, select All Apps, scroll down to the letter S, and select Settings there.) Select Update & Security, Advanced Options, and check Give Me Updates for Other Microsoft Products when I Update Windows. Select Choose How Updates Are Delivered, and select PCs On My Local Network (so your Internet bandwidth isn’t used up delivering updates to random peoples’ computers). Then, click the back arrow in the taskbar (right next to the Start button) twice, and select Check for Updates.

The Windows Update panel might say that updates are available. They will be downloaded and installed. If the panel says A Restart Has Been Scheduled, scroll down and click Restart Now. Wait for the download, install, and restart process to complete before continuing our tour of Windows 10. If Windows wants to restart, select Restart Now. When Windows starts again, sign in and immediately return to Windows Update to see whether any additional updates are available. You might have to repeat this process several times with a brand-new computer or installation. It’s essential that you get all security fixes installed before proceeding.

You should know that installing updates from Windows Update is no longer optional. On Windows 10 Home, they’re installed automatically. On Windows 10 Pro and Enterprise, you can delay them but not defer them indefinitely. There is, however, an option to prevent installation of specific updated device drivers.

![]() To read about the (limited) ways you can control updates, see “Configuring Automatic Updates,” p. 629.

To read about the (limited) ways you can control updates, see “Configuring Automatic Updates,” p. 629.

Be sure to check out the inside front cover of this book to see how we’ll track Windows as it evolves.

Personalizing Windows 10

For the next part of your first hour with Windows 10, we want to help you make changes to some settings that make Windows easier and faster to use and understand. With a little touching up, you can then spend more time looking through the computer’s screen at what you’re working on, and less time looking at the screen trying to make the computer do what you want it to do. So, in this section we’ll tear through some tweaks and adjustments.

To start with, you might to change the screen background or set up a screensaver.

Personalize Screen Settings

Now we’re ready to make a couple of quick selections to the settings that control the Windows appearance. To do this, right-click or touch and hold the desktop anywhere but on an icon or in the taskbar, and then select Personalize.

![]() Note

Note

If you have a desktop computer, you can put its unused computer processor cycles to better use than making the Windows logo swim around your screen. Several worthy screensaver alternatives actually might help find a cure for cancer or eavesdrop on ET phoning home. You can find our favorites at http://boinc.berkeley.edu.

You can select a theme, which is a collection of desktop and sound settings, and/or you can customize individual settings, such as the desktop background, by selecting the categories at the left side of the window. To choose what your computer screen shows when you’re not actively signed in, select Lock Screen. You can select a background picture and enable apps such as Weather and Calendar to display notifications on the screen. To designate a screen saver program, select Screen Saver Settings.

Resolution

In addition to changing the appearance of the display, you can change its physical characteristics, such as its resolution (that is, how many pixels make up the display).

Windows should automatically use the highest resolution (smallest pixels) your monitor can display, but you can change the resolution manually. Using a lower resolution than the monitor’s maximum can result in a somewhat blurry display image on LCD monitors.

To change the display settings, right-click the desktop and select Display Settings. From here, you can drag a slider to change the size of text, apps, and other items. Making them larger makes the display easier to read without changing the resolution. (See the “Font Size” section later in this chapter for details.) You can also adjust the screen orientation (portrait or landscape) and adjust the display brightness (if it’s a portable PC).

To change the resolution, select Advanced Display Settings. (You might need to scroll the right pane down to see this choice.) Open the Resolution drop-down list and select the desired resolution. Then select Apply. If the screen goes black and doesn’t come back, don’t touch anything; just wait a bit and it will revert to the previous setting. If the display does work and you want to keep it, select Keep Changes.

Multiple Monitors

If you have two or more monitors attached to your computer, Windows should have offered you the option of extending your desktop onto all of them. If not, follow these steps:

1. Under Multiple Displays, select Extend These Displays and then click Apply.

2. Select Identify, and then drag the numbered icons in the top pane so that they are in the same arrangement as your monitors. Click Apply again.

You can select the numbered icons in the top pane and adjust the corresponding monitors’ resolution independently.

Font Size

The problem with using the default (highest) resolution on a screen is that the text and icons appear very small. If you have trouble seeing what’s going on, select the Back button to go back to Customize Your Display (the top-level screen for the Display category). Adjust the slider under Change the Size of Text, Apps and Other Items from 100 to 125%, and then click Apply.

This setting changes the general size of text and graphical elements used on the desktop, Start menu, and apps. To get more fine-grained control of the size of text in individual parts of apps, select Advanced Display Settings, and under Related Settings (you might need to scroll down), select Advanced Sizing of Text and Other Items. The descriptive text under Change Size of Text has helpful suggestions.

ClearType Tuner

Finally, use the nifty ClearType Tuner tool to ensure that the text displayed on your monitor is sharp and easy to read. Each pixel on an LCD screen is actually composed of three smaller pixels, one red, one green, and one blue. By finely adjusting the color displayed in the pixels around the edges of each letter, ClearType ekes out a bit of extra resolution from the screen. Because different screens have different arrangements of the colors within each pixel, to get the most out of the technology you must do a one-time adjustment (well, once for each different monitor you use). Here’s what to do:

1. Scroll down and select Advanced Display Settings. If you have multiple monitors, select the icon for display 1. Scroll down and select ClearType Text. This starts the ClearType Text Tuner.

![]() Note

Note

If you’re interesting in seeing how ClearType works, check out www.grc.com/cleartype.htm for the geeky details. The “Free & Clear” demo program you can download from the site is fun to play with.

2. Be sure that Turn On ClearType is checked, and then click Next. Follow the wizard’s instructions to select the text layout that looks best to you. (It’s like an getting an eye exam: The doctor keeps asking “Which looks better?” but they look just the same to you. Don’t worry; just look at the selections and choose one that seems easy on your eyes.) Click Finish when you’re done.

3. If you have multiple monitors, scroll up, select the next monitor icon, and repeat the process.

You will want to repeat this process if you get a replacement monitor, or if you connect to a video projector to make a presentation and want to project the best possible image.

Now, we’ll make some other adjustments to the desktop.

Tune Up the Taskbar, Action Center, and Start Menu

You might want to take a moment now to add taskbar icons for the programs you use frequently. These shortcuts can let you get to work using your favorite tools with just a single click or touch of the screen.

![]() Note

Note

The old Show Desktop icon that parks all applications in the taskbar is now the un-labeled rectangle at the far right.

Personally, I always add taskbar icons for the Command Prompt, File Explorer, and Microsoft Word because I use these frequently, but you might have other favorites. To add an application’s icon, search for the app using the taskbar’s search function, and then right-click it or touch and hold it. Then, select Pin to Taskbar.

The Action Center shows you important notifications from Windows and also gives you Quick Action buttons to open commonly used tools. To open it, click or touch the Action Center icon ![]() in the notification area. Or, if you have a touchscreen, swipe in from just outside the right edge of the screen toward the center. At the bottom, notice that there are rectangular buttons, as shown in Figure 3.7, which are called the Quick Action buttons. These provide a fast way to get to frequently changed settings.

in the notification area. Or, if you have a touchscreen, swipe in from just outside the right edge of the screen toward the center. At the bottom, notice that there are rectangular buttons, as shown in Figure 3.7, which are called the Quick Action buttons. These provide a fast way to get to frequently changed settings.

To customize the Quick Action buttons that appear, open the Action Center as just described and select All Settings. Select System and then Notifications & Actions. Under Choose Your Quick Actions, click on the four icons in turn and select which function you’d like to see in the Action Center. Choose the items that make the most sense to you: certainly All Settings; Airplane Mode for tablets, laptops and phones; Tablet Mode if you have a tablet or a touchscreen computer with a small screen; VPN if you connect to a network at work.

I also suggest that you put some commonly used tools and folders right on the Start menu, for even faster access. You’ll use them all the time. To customize the Start menu, click Start, Settings, Personalization, Start (in the left panel), and then Choose Which Folders Appear on Start.

From the list of items that appear, you might want to select File Explorer, Settings, and Documents, at least. You can select more, but the more of these icons you enable, the less room your Start menu will have for other things. Click X to close the settings panel. You must sign out and then sign back in to see these changes. Figure 3.8 shows the Start menu after I enabled a few of these items.

Store to OneDrive or This PC

If you are using a Microsoft account to sign in, you have the option of saving new documents, music, pictures, and videos and other content to either your regular user account folders (Documents, Music, and so on) or to a matching set of folders in your OneDrive folder. If you save files in OneDrive, they’re also stored online, so they will be copied to any other devices you use with the same Microsoft account.

Having online access from anywhere in the world can be a great thing, but only you can decide whether you want your files copied to a big U.S. corporation’s data centers where they could conceivably eventually be read by friendly or unfriendly governments or criminals. This might be unlikely, but it’s certainly not out of the realm of possibility, and you might never even know whether it happens.

By default, Modern and Desktop apps will try to save new files into a folder inside your OneDrive folder. Thus, the saved files will make their way up to Microsoft’s servers, and then to other devices you use. If you don’t want this to happen, when you save a new file you must manually select a folder outside your OneDrive folder.

You can also choose to set the default save location to another drive entirely (such as a second disk drive or a removable SD card or Flash drive). To do this, click Start, Settings, System, Storage. Under Save Locations, you can set any or all of the entries to This PC (C:), which defaults the new file save location to the OneDrive folder in your user account profile, or another separate disk drive. This just sets the default file save location, which is the easiest to use. Later, you can always choose the folder into which an app saves any individual file, on a file-by-file basis.

By the way, at the time this was written, OneDrive in Windows 10 is missing a lot of expected features, such as the capability to choose to pull only some of your online files down to your computer. Microsoft intends to improve it in a future update.

Privacy Settings

The preceding discussion of OneDrive brings us to the general topic of privacy. Windows 10, more than any previous version of Windows, is set up to send lots of information to Microsoft—not only your documents and other files, but your Internet shortcuts, online and local hard disk search topics, physical location, email and phone contacts and calendar appointments, the Wi-Fi networks and apps you use, what you were doing when Windows ran into trouble, and more. Much of this data collection is done, reasonably, to give you seamless and ubiquitous access to your data and content and to help Microsoft provide a constantly improving, quality experience.

Still, you must understand that everything that goes into and out of your computer, and everything you look at and do with your computer and where and when you do it, is being analyzed, and possibly recorded and stored somewhere. Microsoft has access to it, and if you’ve been following the news lately, you have to expect that criminals and agencies of various governments currently have or could eventually get explicit or covert access to it. You can imagine the news flash, I’m sure: “Data breach reveals personal information of 1 billion Windows users, researchers believe it was the work of the <fill in name of a random country> Army.” So, you must decide whether this data sharing is agreeable to you. If not, you can control it to some extent, if not totally. Here are some ways that you could limit the amount of information that Windows shares with Microsoft and other online services. You’ll pay the price in limited functionality, but this should be your choice to make:

![]() Use a local account rather than a Microsoft account.

Use a local account rather than a Microsoft account.

![]() Do not set up cloud file storage services like OneDrive, Dropbox, and so on.

Do not set up cloud file storage services like OneDrive, Dropbox, and so on.

![]() Use web-based email or a trusted Desktop-style mail program rather than a Modern app, whose privacy policies might not be disclosed.

Use web-based email or a trusted Desktop-style mail program rather than a Modern app, whose privacy policies might not be disclosed.

![]() Be wary of Modern apps in general, because many record your usage and track your location.

Be wary of Modern apps in general, because many record your usage and track your location.

![]() Review and change Windows privacy settings to restrict the types of information that Windows can share.

Review and change Windows privacy settings to restrict the types of information that Windows can share.

To review privacy settings, click or touch Start, Settings, Privacy. There are just four settings here, and you should probably leave SmartScreen Filter turned on. It transmits the URL of websites you visit to Microsoft, but it does a good job of helping you avoid criminally hacked sites. However, these are by no means the only important settings. In the Settings window’s search box type the word privacy. At the time this was written, Windows displays 21 different setting categories that affect privacy. You can review and consider each of them. Then, search for the word sync, and you will have 10 more important categories to consider.

Important Adjustments and Tweaks

With the major adjustments discussed in the previous sections out of the way, you are down to just a few minor adjustments. These are items that aren’t absolutely required, but I’ve found over years of working with Windows to be important enough that I go through them on every computer I use.

Command Prompt or Windows PowerShell

Are you a command-line guru? If you’re not, skip this one. If you are, adjust the Windows Logo+X management menu to show your preferred environment: Command Prompt or Windows PowerShell. To change this, right-click the taskbar in an empty space, select Properties, select the Navigation tab, check or uncheck Replace Command Prompt with Windows PowerShell, and then click OK.

Enable Libraries

As we mentioned previously, if you want to use the Libraries feature in File Explorer, open File Explorer from the taskbar or Start menu, and then select View (along the top of the window), and then Options in the ribbon. In the General tab, check Show Libraries under Navigation Pane, and then click OK.

Show Extensions for Known File Types

By default, File Explorer hides the file extension at the end of most filenames. This is the .doc at the end of a Word document, the .xls at the end of an Excel spreadsheet, or the .exe at the end of an application program. Hiding the extension makes it more difficult for you to accidentally delete it when renaming the file, but we think it also makes it more difficult to tell what a given file is. It can also make it easier to fall for ruses, as when someone sends you a virus program in a file named payroll.xls.exe. If Explorer hides the .exe part, you might fall for the trick and think the file is just an Excel spreadsheet.

To make File Explorer show filenames in all their glory, follow these steps:

1. Open File Explorer from the taskbar or Start menu.

2. At the top, select View, and in the Show/Hide section, check File Name Extensions.

3. Make a mental note that you can use this same settings section to let you see hidden files and folders, which Window normally doesn’t display. (Files are marked hidden when they’re useful to software but not generally interesting to humans.) Just check Hidden Items to make them visible.

4. This one is optional: If you’re curious about the Windows internal files and folders and plan on investigating them, you can tell File Explorer to display “super-hidden” files and folders. These are items that Windows has marked as, in effect, uninteresting to users and of critical importance to Windows. To show them, at the right end of the View ribbon select Options, Change Folder and Search Options. Select the View tab, and scroll the list of Advanced Settings down. Uncheck Hide Protected Operating System Files (Recommended), click Yes, then OK.

Set Web Browser and Home Pages

With Windows 10, Microsoft is trying to move users to its new Edge web browser. In the long term, Edge should be more secure and more stable than Internet Explorer because it doesn’t support the software plug-ins that extend Internet Explorer’s capabilities. The plug-in mechanism has unfortunately also been a constant source of annoyance because spammers, criminals, and hackers have used it to hijack web searches and install advertising pop-ups, viruses, extortion software, and worse. But, in the near term, you might feel that Edge isn’t quite ready for prime time. Many websites don’t function properly with it, and some corporate tools require custom plug-ins.

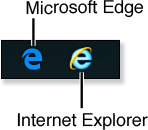

Take a look at your taskbar and compare its icons to those shown in Figure 3.9. The Microsoft Edge icon has a break in it. The Internet Explorer icon has a sort of orbit around it.

Figure 3.9 Windows 10 comes with two web browsers, Internet Explorer and Microsoft Edge. Note the difference between the two icons.

By default, the Microsoft Edge icon should appear in the taskbar. If you want Internet Explorer as well, and its icon doesn’t also appear, in the taskbar’s search box type the word internet. In the search results, right-click or touch and hold Internet Explorer, and select Pin to Taskbar. You might also want to repeat the process and select Pin to Start.

As initially installed, whenever you open either Microsoft Edge or Internet Explorer, it immediately displays a Microsoft website or a website specified by your computer manufacturer. Personally, I prefer to have my web browser open to a blank page because I rarely start my browsing in the same place twice. You also might want to select a different home page, one that you want to visit rather than one selected by some company’s marketing department.

To take control of Internet Explorer’s startup page, follow the steps under “Changing the Home Page” on page 328.

To configure the startup page in Microsoft Edge, select the ... icon at the upper right, and then select Settings. Under Start With, select A Specific Page or Pages, and from the drop-down list select Custom. In the box under Custom, to have Edge open to a blank screen, type about:blank; otherwise, type in the URL you want.

You might also want to download and install a different web browser entirely. Safari, Chrome, Firefox, and Opera are popular alternatives.

Search Providers

Microsoft Edge and Internet Explorer have a search tool built right in to the URL address box. If you type something that doesn’t look like a URL and press Enter, the browser sends the text to an Internet search engine and displays the results. This saves you from having to open the search engine page first, type the search text, and then wait for the results.

By default, Microsoft sets up its browsers to send you to Microsoft’s own search engine, called Bing. (Or your computer manufacturer might have specified a different default search engine.) Again, we suggest that you take control and tell Edge and IE which search engine you want to use. You can use Bing, of course, but you can also select a different default site.

To change the default search provider for Internet Explorer, follow the instructions under “Searching the Web” on page 319.

To change the default search provider for Microsoft Edge, click the ... icon at the upper right, select Settings, scroll down, and select Advanced Settings. Scroll the Advanced Settings down until you can see Search In the Address Bar With. Open the dropdown list and select Add New. The list of search providers may be smaller than available for Internet Explorer at first, but it should grow as Microsoft and search companies work to make more options available.

Enable System Restore

By default, System Restore, which lets you roll back system changes and updates that cause problems, is not enabled. To enable it, right-click or touch and hold the Start button, then select System. At the left, select System Protection. In the Protection Settings list, select the C: drive and select Configure. Check Turn On System Protection, and set a Max Usage value of about 5%. Click OK to save the changes.

Enable Metering for Cellular Data

If your device uses a cellular data service that has monthly limits, Windows can defer some downloads and uploads until you’re hooked up to an unlimited Wi-Fi or Ethernet network. To change the setting, select Start, Settings, Network & Internet, and select the category for your cellular data connection. Select Advanced Options, and be sure that Set as a Metered Connection is turned on.

If necessary, you can set other connection types, such as Wi-Fi, as metered also. When the list of potential connection names appears (as is usually the case on the Wi-Fi page), the Metered Connection setting applies only to the currently active connection.

That’s the end of our list of “must do” Windows settings. You can, of course, change hundreds of other things, which is why we went on to write Chapters 4 through 39.

Transferring Information from Your Old Computer

If you have set up a new Windows 10 computer rather than upgrading an old one, you probably have files you want to bring over to your new computer.

If your old computer has Windows 7, 8, or 8.1, you might have noticed that it has a program called Windows Easy Transfer, which lets you package up your user accounts, files, and settings for transfer to a new computer. Unfortunately, Windows 10 does not have the “receiving” end of Windows Easy Transfer, so it’s useless now.

Here are some options you might use instead, to move your stuff from an old computer to a new computer with Windows 10:

![]() On the old computer, you can copy files to cloud-based storage like OneDrive, Google Drive, Dropbox, or the like. If you install the same cloud file storage app on your new computer, the files will automatically be copied to your new computer. This option is easiest, and having your important files in cloud storage is great because you can then get to them from any device anywhere in the world. But it won’t work if you have more files than will fit in your online storage quota, and can be problematic if your Internet service is slow or limited in the amount of data you can transfer.

On the old computer, you can copy files to cloud-based storage like OneDrive, Google Drive, Dropbox, or the like. If you install the same cloud file storage app on your new computer, the files will automatically be copied to your new computer. This option is easiest, and having your important files in cloud storage is great because you can then get to them from any device anywhere in the world. But it won’t work if you have more files than will fit in your online storage quota, and can be problematic if your Internet service is slow or limited in the amount of data you can transfer.

![]() You can manually copy your most important files and folders directly from your old computer to your new computer using a network. This option is fast, and if you set up a Homegroup network as we show you in Chapter 18, it’s pretty easy, but it copies data only, not programs or settings.

You can manually copy your most important files and folders directly from your old computer to your new computer using a network. This option is fast, and if you set up a Homegroup network as we show you in Chapter 18, it’s pretty easy, but it copies data only, not programs or settings.

![]() You can copy files from your old computer to a removable drive, take the removable drive to your new computer, and then copy the files onto the new computer. Like the network method, this copies data only, not settings or programs.

You can copy files from your old computer to a removable drive, take the removable drive to your new computer, and then copy the files onto the new computer. Like the network method, this copies data only, not settings or programs.

We give you some tips for the network or external disk methods later in this section.

![]() You can use a paid third-party program to transfer data, settings, and possibly application programs. These products can copy your user accounts, files, preferences, app data (such as email, if you use an email reading program), and so on. You must pay for these, but they can do a very thorough job, and the vendors provide customer support if you need help. We discuss these options more in the next section.

You can use a paid third-party program to transfer data, settings, and possibly application programs. These products can copy your user accounts, files, preferences, app data (such as email, if you use an email reading program), and so on. You must pay for these, but they can do a very thorough job, and the vendors provide customer support if you need help. We discuss these options more in the next section.

![]() You could venture into some spooky territory. Microsoft has a free program called the User State Migration Tool, meant for use by corporate network managers. It’s difficult to use. If you want to read more about it, go to technet.microsoft.com and search for “User State Migration Tool.”

You could venture into some spooky territory. Microsoft has a free program called the User State Migration Tool, meant for use by corporate network managers. It’s difficult to use. If you want to read more about it, go to technet.microsoft.com and search for “User State Migration Tool.”