33. Protecting Your Network from Hackers and Snoops

It’s a Cold, Cruel World

I have relatives, friends and neighbors who say that growing up, they never locked the front door to their house. What a charming thought! It’s nearly inconceivable today to do this. I don’t think it’s because people have gotten any worse, or that there’s a higher percentage of bad people; it’s that there are just more people. A lot more. The odds have gotten greater that an unlocked door would lead to theft simply because there are more people walking down the street, past your door, and eventually one of them will give it a push.

And here’s the thing: With an Internet connection in your home or business, there are about three billion people and three billion computers able to reach your (virtual) door. The percentage of them who would commit theft or other mayhem may be small, but...do the math. The inescapable truth is that every minute of every day, some hacker, spammer, information bandit, prankster, thief, bottom-feeder, or otherwise bad guy, or, more likely, one of the hundreds of millions of virus-infected computers the bad guys control will probe, prod, and test your defenses. Is your network up to the task?

It can be. Effective network design is foremost a task of planning. It’s especially true in this case: Before you connect to the Internet, you must plan for security, whether you have a single computer or a large local area network (LAN).

![]() Note

Note

You should know this: Even if you don’t have a network but have just one computer that is only occasionally connected to the Internet, you’re still at risk. The material in this chapter applies to almost everyone!

Explaining everything that you can and should do would be impossible. In this chapter, we give you an idea of what network security entails. We talk about the types of risks you’ll be exposed to and the means people use to minimize this exposure; then we end with some tips and to-do lists. If you want to have a network or security consultant take care of implementation for you, that’s great. This chapter gives you the background to understand what the consultant is doing. If you want to go it on your own, consider this chapter to be a survey course, with your assignment to continue to research, write, and implement a security plan.

![]() Tip

Tip

This chapter gives you a good background on the ways that the “bad guys” can get into your computer and cause damage. If you don’t want to read about this, skip ahead to “Specific Configuration Steps for Windows 10,” later in the chapter. If even that’s too much, we can give you the short version in one paragraph:

Windows 10 has far better security than, say, Windows XP, right out of the box. Don’t turn off User Account Control (UAC), Windows Firewall, Windows Defender, or automatic Windows Updates, which are turned on by default, no matter what anyone else tells you. Do back up your hard disk frequently. If you do that and make no changes to Microsoft’s default security settings, you’ll be better off than 95% of the people out there.

Who Would Be Interested in My Computer?

Most of us don’t give security risks a second thought. After all, who is a data thief going to target: me or the Pentagon? Who’d be interested in my computer? Well, the sad truth is that thousands of people out there would be delighted to find that they could connect to your computer. They might be looking for your credit card information, passwords for computers and websites, or a way to get to other computers on your LAN. Even more, they would love to find that they could install software on your computer that they could then use to send spam and probe other people’s computers. They might even use your computer to launch attacks against corporate or governmental networks. Don’t doubt that this could happen to you. Much of the spam you receive is sent from home computers that have been taken over by criminals through the conduit of an unsecured Internet connection. An estimated 5% to 33% of computers worldwide are infected with malware. (So, tens of millions to hundreds of millions of infected computers.)

For a decade Microsoft shrugged off any responsibility for preventing this, but starting with Windows XP Service Pack 2, Microsoft started enabling the strictest network security settings by default instead of requiring you to take explicit steps to enable them. And with the advent of high-speed, always-on Internet connections, the risks were increasing because computers stayed connected and exposed for longer periods of time.

If your computer is connected to a Windows domain-type network, your network administrators probably have taken care of all this for you. In fact, you might not even be able to make any changes in your computer’s network or security settings. If this is the case, even if you’re not too interested in this topic and don’t read any other part of this chapter, you should read and carry out the steps in the section “Specific Configuration Steps for Windows 10.”

Windows Vista introduced User Account Control (UAC), which requires the user to respond to a prompt before the system will change sensitive system settings or install software, thereby making sure the user is aware of and approves the action. UAC also provides a mechanism to run some programs (especially network- and Internet-connected programs) with lower than normal privileges, so that if the program gets compromised, it can do less damage to files and other software on the computer. Other steps were taken to help block the methods that viruses use to gain control of the operating system. These technical defenses have been improved upon with each successive version of Windows.

Starting with Windows 7, Microsoft improved things further by having Windows automatically batten down the hatches again anytime it detects that it has been connected to a new network (for example, at a Wi-Fi hotspot or a friend’s home). You must explicitly open things up by telling Windows that the new network is safe. This feature is called Network Location, and we discuss it later in the chapter.

In this chapter, we explain a bit about how network attacks and defenses work. We tell you ways to prevent and prepare for recovery from a hacker attack. And most importantly, we show you what to do to make your system secure.

If outside attacks weren’t enough, in a business environment, security risks can come from inside a network environment as well as from outside. Inside, you might be subject to highly sophisticated eavesdropping techniques or even simple theft. I know of a company whose entire customer list and confidential pricing database walked out the door one night with the receptionist, whose significant other worked for the competition. The theft was easy; at the time, any employee could read and print any file on the company’s network. Computer security is a real and serious issue. And it only helps to think about it before things go wrong.

Types of Attack

Before we talk about how to defend your computer against attack, let’s briefly go through the types of attacks you’re facing. Hackers can work their way into your computer and network using several methods. Here are some of them:

![]() Password cracking—Given a user account name, so-called cracking software can tirelessly try dictionary words, proper names, and random combinations in the hope of guessing a correct password. If your passwords aren’t complex (that is, if they’re not composed of a combination of upper- and lowercase letters, numbers, and punctuation characters), this doesn’t take long to accomplish. If you make your computer(s) accessible over the Internet via Remote Desktop or if you run a public FTP, web, or email server, I can promise you that you will be the target of this sort of automated attack.

Password cracking—Given a user account name, so-called cracking software can tirelessly try dictionary words, proper names, and random combinations in the hope of guessing a correct password. If your passwords aren’t complex (that is, if they’re not composed of a combination of upper- and lowercase letters, numbers, and punctuation characters), this doesn’t take long to accomplish. If you make your computer(s) accessible over the Internet via Remote Desktop or if you run a public FTP, web, or email server, I can promise you that you will be the target of this sort of automated attack.

![]() Address spoofing—If you’ve seen the caller ID service used on telephones, you know that it can be used to screen calls: You answer the phone only if you recognize the caller. But what if telemarketers could make the device say “Mom’s calling”? There’s an analogy to this in networking. Hackers can send “spoofed” network commands into a network with a trusted IP address.

Address spoofing—If you’ve seen the caller ID service used on telephones, you know that it can be used to screen calls: You answer the phone only if you recognize the caller. But what if telemarketers could make the device say “Mom’s calling”? There’s an analogy to this in networking. Hackers can send “spoofed” network commands into a network with a trusted IP address.

![]() Impersonation—By tricking Internet routers and the domain name registry system, hackers can have Internet or network data traffic routed to their own computers instead of the legitimate website server. With a fake website in operation, they can collect credit card numbers and other valuable data. This type of attack is on the rise due to vulnerabilities in the Internet’s basic infrastructure.

Impersonation—By tricking Internet routers and the domain name registry system, hackers can have Internet or network data traffic routed to their own computers instead of the legitimate website server. With a fake website in operation, they can collect credit card numbers and other valuable data. This type of attack is on the rise due to vulnerabilities in the Internet’s basic infrastructure.

![]() Eavesdropping—Wiretaps on your telephone or network cable, or monitoring of the radio emissions from your computer and monitor, can let the more sophisticated hackers and spies see what you’re seeing and record what you’re typing. This sounds like KGB/CIA-type stuff, but wireless networks, which are everywhere these days, are extremely vulnerable to eavesdropping.

Eavesdropping—Wiretaps on your telephone or network cable, or monitoring of the radio emissions from your computer and monitor, can let the more sophisticated hackers and spies see what you’re seeing and record what you’re typing. This sounds like KGB/CIA-type stuff, but wireless networks, which are everywhere these days, are extremely vulnerable to eavesdropping.

![]() Exploits—It’s a given that complex software has bugs. Some bugs make programs fail in such a way that part of the program itself gets replaced by data from the user. Exploiting this sort of bug, hackers can run their own software on your computer, without your knowledge or permission. It sounds farfetched, but exploits in Microsoft’s products alone are reported about once a week. Add-on products such as Adobe Acrobat Viewer, Adobe Flash Player, and Oracle’s Java have also been responsible for a huge number of exploits, because virtually every computer in the world has these programs, and their earlier versions didn’t automatically seek and install updates.

Exploits—It’s a given that complex software has bugs. Some bugs make programs fail in such a way that part of the program itself gets replaced by data from the user. Exploiting this sort of bug, hackers can run their own software on your computer, without your knowledge or permission. It sounds farfetched, but exploits in Microsoft’s products alone are reported about once a week. Add-on products such as Adobe Acrobat Viewer, Adobe Flash Player, and Oracle’s Java have also been responsible for a huge number of exploits, because virtually every computer in the world has these programs, and their earlier versions didn’t automatically seek and install updates.

Security researchers try to stay ahead of the hackers by finding exploits and reporting them to the responsible manufacturer before they get used “in the wild,” but you’ll often see reports of bugs that are detected only after criminals have started to use them. These are called “zero-day” exploits, meaning, zero days elapsed between their detection and their exploitation. You can be sure that even the most up-to-date copy of Windows has exploits just waiting to be used.

![]() Backdoors—Some software developers put special features into programs intended for their use only, usually to help in debugging. These backdoors sometimes circumvent security features. Hackers discover and trade information on these and are only too happy to use the Internet to see if they work on your computer. It is also widely believed that some government agencies insist that encryption and security software have backdoors for use by said government agencies. How would you know?

Backdoors—Some software developers put special features into programs intended for their use only, usually to help in debugging. These backdoors sometimes circumvent security features. Hackers discover and trade information on these and are only too happy to use the Internet to see if they work on your computer. It is also widely believed that some government agencies insist that encryption and security software have backdoors for use by said government agencies. How would you know?

![]() Open doors—All the attack methods described previously involve direct and malicious actions to try to break into your system. But this isn’t always necessary: Sometimes, a computer can be left open in such a way that it just offers itself to the public. Just as leaving your front door wide open might invite burglary, leaving a computer unsecured by passwords and without proper controls on network access allows hackers to read and write your files by the simplest means. Password Protected Sharing, which we discuss later in the chapter, mitigates this risk somewhat.

Open doors—All the attack methods described previously involve direct and malicious actions to try to break into your system. But this isn’t always necessary: Sometimes, a computer can be left open in such a way that it just offers itself to the public. Just as leaving your front door wide open might invite burglary, leaving a computer unsecured by passwords and without proper controls on network access allows hackers to read and write your files by the simplest means. Password Protected Sharing, which we discuss later in the chapter, mitigates this risk somewhat.

![]() Viruses and Trojan horses—The ancient Greeks came up with the idea 3,200 years ago, and the Trojan horse trick is still alive and well today. Shareware programs used to be the favored way to distribute disguised attack software, but today email attachments and websites are the favored method. Most email providers automatically strip out obviously executable email attachments, so the current trend is for viruses to send their payloads in ZIP file attachments. File- and music-sharing programs, Registry cleanup tools, and other “free” software utilities are another great source of unwanted add-ons commonly called spyware, adware, and malware. You may also hear the term rootkit, which refers to a virus that burrows so deeply into the operating system that it can prevent you from detecting its presence when you list files or active running programs. Other sources of viruses are hacked or malicious websites that use Internet Explorer or media player exploits to install malware just by viewing the site. Sometimes legitimate, high-volume websites get hacked to do this (so-called drive-by attacks, where you get infected just doing innocent web browsing), or links to these sites are sent in spam and phishing email.

Viruses and Trojan horses—The ancient Greeks came up with the idea 3,200 years ago, and the Trojan horse trick is still alive and well today. Shareware programs used to be the favored way to distribute disguised attack software, but today email attachments and websites are the favored method. Most email providers automatically strip out obviously executable email attachments, so the current trend is for viruses to send their payloads in ZIP file attachments. File- and music-sharing programs, Registry cleanup tools, and other “free” software utilities are another great source of unwanted add-ons commonly called spyware, adware, and malware. You may also hear the term rootkit, which refers to a virus that burrows so deeply into the operating system that it can prevent you from detecting its presence when you list files or active running programs. Other sources of viruses are hacked or malicious websites that use Internet Explorer or media player exploits to install malware just by viewing the site. Sometimes legitimate, high-volume websites get hacked to do this (so-called drive-by attacks, where you get infected just doing innocent web browsing), or links to these sites are sent in spam and phishing email.

![]() Phishing and social engineering—A more subtle approach than brute-force hacking is to simply call or email someone who has useful information and ask for it. One variation on this approach is called phishing, in which the criminals send email that purports to come from a bank or other service provider, saying there was some sort of account glitch and asking the user to reply with her password and Social Security number so the glitch can be fixed. P. T. Barnum said there’s a sucker born every minute. Sadly, this works out to 1,440 suckers per day, or more than half a million per year, and it’s not too hard to reach a lot of them with one bulk email. For more information about phishing, see Chapter 34, “Protecting Yourself from Fraud and Spam.”

Phishing and social engineering—A more subtle approach than brute-force hacking is to simply call or email someone who has useful information and ask for it. One variation on this approach is called phishing, in which the criminals send email that purports to come from a bank or other service provider, saying there was some sort of account glitch and asking the user to reply with her password and Social Security number so the glitch can be fixed. P. T. Barnum said there’s a sucker born every minute. Sadly, this works out to 1,440 suckers per day, or more than half a million per year, and it’s not too hard to reach a lot of them with one bulk email. For more information about phishing, see Chapter 34, “Protecting Yourself from Fraud and Spam.”

![]() Denial of service (DoS)—Every hacker is interested in your credit cards or business secrets. Some are just plain vandals, however, and it’s enough for them to know that you can’t get your work done. They might erase your hard drive or, more subtly, crash your server or tie up your Internet connection with a torrent of meaningless data. In any case, you’re inconvenienced.

Denial of service (DoS)—Every hacker is interested in your credit cards or business secrets. Some are just plain vandals, however, and it’s enough for them to know that you can’t get your work done. They might erase your hard drive or, more subtly, crash your server or tie up your Internet connection with a torrent of meaningless data. In any case, you’re inconvenienced.

![]() Identity theft—Hackers often attempt to steal personal information, such as your name, date of birth, address, credit card, and Social Security number. Armed with this information, they can proceed to open credit card and bank accounts, redirect your mail, take over your email and social networking accounts, obtain services, purchase goods, claim your tax refund, and so on, all without your knowledge. This is one of the most vicious attacks and can have a profound and lasting effect on victims. Computers can expose you to identity theft in several ways: You might provide personal information to a phishing scheme or to an unscrupulous online seller yourself. Hackers can break into your computer or that of an online seller and steal your information stored there. Criminals can even tap into your home or business network, a wireless network in a public space, or even the wiring at an Internet service provider and capture unencrypted information flowing through the network there.

Identity theft—Hackers often attempt to steal personal information, such as your name, date of birth, address, credit card, and Social Security number. Armed with this information, they can proceed to open credit card and bank accounts, redirect your mail, take over your email and social networking accounts, obtain services, purchase goods, claim your tax refund, and so on, all without your knowledge. This is one of the most vicious attacks and can have a profound and lasting effect on victims. Computers can expose you to identity theft in several ways: You might provide personal information to a phishing scheme or to an unscrupulous online seller yourself. Hackers can break into your computer or that of an online seller and steal your information stored there. Criminals can even tap into your home or business network, a wireless network in a public space, or even the wiring at an Internet service provider and capture unencrypted information flowing through the network there.

If all this makes you nervous about connecting to the Internet, we’ve done our job well. Before you pull the plug, though, read on.

Your Lines of Defense

Making your computer and network completely impervious to all these forms of attacks is quite impossible, if for no other reason than that there is always a human element that you cannot control, and there are always bugs and exploits not yet anticipated.

You can do a great deal, however, if you plan ahead. Furthermore, as new software introduces new features and risks, and as existing flaws are identified and repaired, you have to keep on top of things to maintain your defenses. The most important part of the process is that you spend some time thinking about security.

The following sections delve into the four main lines of computer defense:

![]() Preparation

Preparation

![]() Active defense

Active defense

![]() Testing, logging, and monitoring

Testing, logging, and monitoring

![]() Disaster planning

Disaster planning

You can omit any of these measures, of course, if you weigh what you have at risk against what these efforts will cost you, and decide that the benefit isn’t worth the effort.

What we’re describing sounds like a lot of work, and it can be if you take full-fledged measures in a business environment. Nevertheless, even if you’re a home user, we encourage you to consider each of the following steps and to put them into effect with as much diligence as you can muster.

Preparation: Network Security Basics

Preparation involves eliminating unnecessary sources of risk before they can be attacked. You should take the following steps:

![]() Invest time in planning and policies. If you want to be really diligent about security, for each of the strategies we describe in this chapter, outline how you plan to implement each one.

Invest time in planning and policies. If you want to be really diligent about security, for each of the strategies we describe in this chapter, outline how you plan to implement each one.

![]() Structure your network to restrict unauthorized access. Do you really need to allow users to remotely gain access to your network via a virtual private network (VPN) or Remote Desktop, or can you forego this? Eliminating points of access reduces risk but also convenience. You have to decide where to strike the balance.

Structure your network to restrict unauthorized access. Do you really need to allow users to remotely gain access to your network via a virtual private network (VPN) or Remote Desktop, or can you forego this? Eliminating points of access reduces risk but also convenience. You have to decide where to strike the balance.

![]() If you’re concerned about unauthorized in-house access to your computers, be sure that every user account is set up with a good password—one with a combination of uppercase and lowercase letters and numbers and punctuation. You must also ensure that an effective firewall is in place between your LAN and the Internet. We show you how to use Windows Firewall later in this chapter.

If you’re concerned about unauthorized in-house access to your computers, be sure that every user account is set up with a good password—one with a combination of uppercase and lowercase letters and numbers and punctuation. You must also ensure that an effective firewall is in place between your LAN and the Internet. We show you how to use Windows Firewall later in this chapter.

![]() Install only needed services. The less network software you have installed, the less you’ll have to maintain through updates, and the fewer potential openings you’ll offer to attackers. For example, don’t install SNMP or Internet Information Services (IIS) unless you really need them. Don’t install the optional Simple TCP Services network service; it provides no useful function, only archaic services that make great DoS attack targets.

Install only needed services. The less network software you have installed, the less you’ll have to maintain through updates, and the fewer potential openings you’ll offer to attackers. For example, don’t install SNMP or Internet Information Services (IIS) unless you really need them. Don’t install the optional Simple TCP Services network service; it provides no useful function, only archaic services that make great DoS attack targets.

The most important program to keep up to date is Windows itself. We suggest that you keep up to date on Windows bugs and fixes through the Automatic Updates feature and through independent watchdogs. On Windows 10 Home, this isn’t optional. Windows will download and install all updates. On Windows 10 Pro and Enterprise, we recommend that you do not defer updates unless you have very good reason to and have excellent perimeter defenses. (And no pesky users, who tend to mess things up no matter what you do.)

Subscribe to the free security bulletin mailing lists at www.microsoft.com/security and www.sans.org. I personally also check my computer with http://browsercheck.qualys.com every few weeks. This web-based tool examines Internet Explorer and plug-ins for web-based applications, and lets you know if you’re not up to date.

If you use Microsoft IIS to host a website, pay particular attention to announcements regarding Internet Explorer and IIS. Internet Explorer and IIS together account for the lion’s share of Windows security problems.

![]() Use software known to be secure and (relatively) bug-free. Use the Windows Automatic Updates feature. For every software application you use, proactively check the manufacturers’ websites for updates, and install updates promptly when they become available. Be very wary of shareware and freeware, unless you can be sure of its pedigree and safety.

Use software known to be secure and (relatively) bug-free. Use the Windows Automatic Updates feature. For every software application you use, proactively check the manufacturers’ websites for updates, and install updates promptly when they become available. Be very wary of shareware and freeware, unless you can be sure of its pedigree and safety.

![]() Download software, such as printer and other device drivers, only from the original manufacturer’s own website, not a third-party website, if at all possible.

Download software, such as printer and other device drivers, only from the original manufacturer’s own website, not a third-party website, if at all possible.

![]() Install an antivirus program and keep it updated. You can buy a third-party product, get a free third-party product, or use Microsoft’s free Windows Security Essentials. Whichever program you select, be sure to keep it up to date.

Install an antivirus program and keep it updated. You can buy a third-party product, get a free third-party product, or use Microsoft’s free Windows Security Essentials. Whichever program you select, be sure to keep it up to date.

![]() Properly configure your computers, file systems, software, and user accounts to maintain appropriate access control. We discuss this in detail later in the chapter.

Properly configure your computers, file systems, software, and user accounts to maintain appropriate access control. We discuss this in detail later in the chapter.

![]() Hide from the outside world as much information about your systems as possible. Don’t give hackers any assistance by revealing user account or computer names, if you can help it. For example, if you set up your own Internet domain, put as little information into DNS as you can get away with. Don’t install SNMP unless you need it, and be sure to block it at your Internet firewall.

Hide from the outside world as much information about your systems as possible. Don’t give hackers any assistance by revealing user account or computer names, if you can help it. For example, if you set up your own Internet domain, put as little information into DNS as you can get away with. Don’t install SNMP unless you need it, and be sure to block it at your Internet firewall.

Security is partly a technical issue and partly a matter of organizational policy. No matter how you’ve configured your computers and network, one user with a modem and a lack of responsibility can open a door into the best-protected network.

You should decide which security-related issues you want to leave to your users’ discretion and which you want to mandate as a matter of policy. On a Windows domain network, the operating system enforces some of these points, but if you don’t have a domain server, you might need to rely on communication and trust alone. The following are some issues to ponder:

![]() Do you trust users to create and protect their own shared folders, or should this be done by management only?

Do you trust users to create and protect their own shared folders, or should this be done by management only?

![]() Do you want to let users run a web server, an FTP server, or other network services, each of which provides benefits but also increases risk?

Do you want to let users run a web server, an FTP server, or other network services, each of which provides benefits but also increases risk?

![]() Are your users allowed to create simple alphabetic passwords without numbers or punctuation? (You can enforce more complex passwords using a Windows security policy setting.)

Are your users allowed to create simple alphabetic passwords without numbers or punctuation? (You can enforce more complex passwords using a Windows security policy setting.)

![]() Are users allowed to send and receive personal email from the network?

Are users allowed to send and receive personal email from the network?

![]() Are users allowed to install software they obtain themselves?

Are users allowed to install software they obtain themselves?

![]() Are users allowed to share access to their desktops with Remote Desktop, Remote Assistance, TeamViewer, GoToMyPC, LogMeIn, VNC, PCAnywhere, or other remote-control software?

Are users allowed to share access to their desktops with Remote Desktop, Remote Assistance, TeamViewer, GoToMyPC, LogMeIn, VNC, PCAnywhere, or other remote-control software?

Make public your management and personnel policies regarding network security and appropriate use of computer resources.

If your own users don’t respect the integrity of your network, you don’t stand a chance against the outside world. A crucial part of any effective security strategy is making up the rules in advance and ensuring that everyone knows and adheres to them.

Active Defenses

Active defense means actively resisting known methods of attack. Active defenses include these:

![]() Firewalls and gateways to block dangerous or inappropriate Internet traffic as it passes between your network and the Internet at large

Firewalls and gateways to block dangerous or inappropriate Internet traffic as it passes between your network and the Internet at large

![]() Encryption and authentication to limit access based on some sort of credentials (such as a password)

Encryption and authentication to limit access based on some sort of credentials (such as a password)

![]() Efforts to keep up to date on security and risks, especially with respect to Windows but also all installed applications

Efforts to keep up to date on security and risks, especially with respect to Windows but also all installed applications

![]() Antivirus programs to detect and delete malware that makes it through your other defenses

Antivirus programs to detect and delete malware that makes it through your other defenses

When your network is in place, your next job is to configure it to restrict access as much as possible. This task involves blocking network traffic that is known to be dangerous and configuring network protocols to use the most secure communications protocols possible.

Firewalls and NAT (Connection-Sharing) Devices

Using a firewall is an effective way to secure your network. From the viewpoint of design and maintenance, it is also the most efficient tool because you can focus your efforts on one critical place: the interface between your internal network and the Internet.

A firewall is a program or piece of hardware that intercepts all data that passes between two networks—for example, between your computer or LAN and the Internet. The firewall inspects each incoming and outgoing data packet and permits only certain packets to pass. Generally, a firewall is set up to permit traffic for safe protocols such as those used for email and web browsing. It blocks packets that carry file-sharing or computer administration commands.

Network Address Translation (NAT), the technology behind Internet Connection Sharing and connection-sharing routers, insulates your network from the Internet by funneling all of your LAN’s network traffic through one IP address—the Internet analog of a telephone number. Like an office’s switchboard operator, NAT lets all your computers place outgoing connections at will, but it intercepts all incoming connection attempts. If an incoming data request was anticipated, it’s forwarded to one of your computers, but all other incoming network requests are rejected or ignored. Microsoft’s Internet Connection Sharing and hardware Internet Connection Sharing routers all use a NAT scheme.

![]() To learn more about this topic, see “NAT and Internet Connection Sharing,” p. 416.

To learn more about this topic, see “NAT and Internet Connection Sharing,” p. 416.

The use of either NAT or a firewall, or both, can protect your network by letting you specify exactly how much of your network’s resources you expose to the Internet.

Windows Firewall

One of Windows 10’s most important security features is the built-in Windows Firewall software.

Windows Firewall is enabled on every hard-wired, wireless, or dial-up network connection. On those connections that lead directly to the Internet, it blocks virtually all attempts by outside computers to reach your computer, so it prevents computers on the Internet from accessing your shared files, Remote Desktop, Remote Administration, and other “sensitive” functions.

On an Internet-facing connection, Windows Firewall by default blocks all attempts by other computers to reach your computer, except in response to communications that you initiate yourself. For example, if you try to view a web page, your computer starts the process by connecting to a web server out on the Internet. Windows Firewall knows that the returning data is in response to your request, so it allows the reply to return to your computer. However, someone “out there” who tries to view your shared files will be rebuffed. Any unsolicited, incoming connection will simply be ignored.

This type of network haughtiness is generally a good thing, except that it would also prevent you from sharing your computer with the people you do want to share with. For example, it would block file and printer sharing on your home network, Remote Assistance, and other desirable services. So, Windows Firewall can make exceptions that permit incoming connections from other computers on a case-by-case basis. By that, we mean that it can differentiate connections based on the software involved (which is discerned by the connection’s port number) by the remote computer’s network address, which lets Windows know whether the request comes from a computer on your own network or from a computer “out there” on the Internet. Windows Firewall uses a third criterion for judging incoming requests: the “public” or “private” label attached to the particular network adapter through which a request comes.

This is a huge improvement over Windows XP and Vista, and here’s why: When you’re at home, the other computers on your network share a common network address scheme (just as most telephone numbers in a neighborhood start with the same area code and possibly prefix digits). Those computers can be trusted to share your files and printers. However, if you take your computer to a hotel or coffee shop, the other computers on that local network should not be trusted, even though they will share the same network addressing scheme. With Windows Vista and earlier versions, you had to manually reconfigure Windows Firewall every time you moved your computer from one network to another so that you didn’t inadvertently expose your shared files to unknown people.

On Windows 7 through 10, this reconfiguring is automatic. When you connect your computer to a network for the first time, Windows asks you whether the network is private or public, though the question is phrased in a different way on each version of Windows. Windows 10 asks “Do you want to allow your PC to be discoverable by other PCs and devices on this network?” (On Windows 8.1, the question was, unfortunately, “Do you want to find PCs, devices and content on this network?” which seems backward, in my opinion.)

If you say no, Windows labels the network as public, one where you don’t trust the other connected computers. This would be an appropriate choice in a coffee shop or hotel, or for a connection from your computer directly to a DSL or cable modem. If you say yes, Windows assumes you’re using a private network, where you trust the other computers that are directly attached. This network might connect to the Internet through a router, but you can still consider it private because your local trusted computers can be distinguished by sharing a common network address.

![]() Note

Note

Windows Firewall has the advantage that it can permit incoming connections for programs such as Remote Assistance. On the other hand, it’s part of the very operating system it’s trying to protect, and if either Windows or Windows Firewall gets compromised, your computer’s a goner.

Windows Firewall is enabled by default when you install Windows. You can also enable or disable it manually by selecting the Change Settings task on the Windows Firewall window. (We tell you how to do this later in the chapter, under “Specific Configuration Steps for Windows 10.”) You also can tell Windows Firewall whether you want it to permit incoming requests for specific services. If you have a web server installed in your computer, for example, you need to tell Windows Firewall to permit incoming HTTP data.

If you have an external firewall device—such as a commercial firewall server or a connection-sharing router with filter rules—this device will perform firewall duties for you. But, even with this, there is no good reason to disable Windows Firewall. You’re better off using both.

Packet Filtering

If you use a hardware Internet Connection Sharing router (also called a residential gateway) or a full-fledged network router for your Internet service, you can instruct it to block data that carries services you don’t want exposed to the Internet. This is called packet filtering. You can set up this filtering in addition to NAT, to provide an additional layer of protection.

Filtering works like this: Each Internet data packet contains identifying numbers that indicate the protocol type (such as TCP or UDP) and the IP address for the source and destination computers. Some protocols also have an additional number called a port, which identifies the program that is to receive the packet. The WWW service, for example, expects TCP protocol packets addressed to port 80. A domain name server listens for UDP packets on port 53.

A packet that arrives at the firewall from either side is examined; then it is either passed on or discarded, according to a set of rules that list the protocols and ports permitted or prohibited for each direction. A prohibited packet can be dropped silently, or the router can reject the packet with an error message returned to the sender indicating that the requested network service is unavailable. If possible, specify the silent treatment. (Why tell hackers that a desired service is present, even if it’s unavailable to them? In security, silence is golden.) Some routers can also make a log entry or send an alert indicating that an unwanted connection was attempted.

Configuring routers for filtering is beyond the scope of this book, but Table 33.1 lists some relevant protocols and ports. If your router lets you block incoming requests separately from outgoing requests, you should block incoming requests for all the services listed, unless you are sure you want to enable access to them. If you have a basic gateway router that doesn’t provide separate incoming and outgoing filters, you probably want to filter only those services that are marked with an asterisk (*).

As stated earlier, if you use a hardware router to connect to the Internet, we can’t show you the specifics for your device. We can give you a couple of examples, though. My Linksys cable/DSL–sharing router uses a web browser for configuration, and there’s a page for setting up filters, as shown in Figure 33.1. In this figure, I’ve blocked the ports for Microsoft file-sharing services.

If you use routed DSL Internet service, your ISP might have provided a router manufactured by FlowPoint, Cisco, Motorola, or another manufacturer. These are complex devices, and your ISP will help you set up yours. Insist that your ISP install filters for ports 137, 138, 139, and 445, at the very least.

Using NAT or Internet Connection Sharing

By either name, Network Address Translation (NAT) has two big security benefits. First, it can be used to hide an entire network behind one IP address. Then, while it transparently passes connections from you out to the Internet, it rejects all incoming connection attempts except those that you explicitly direct to waiting servers inside your LAN. Packet filtering isn’t absolutely necessary with NAT, although adding it can’t hurt.

![]() Caution

Caution

Microsoft’s Internet Connection Sharing (ICS) blocks incoming access to other computers on the LAN, but unless Windows Firewall is also enabled, it does not protect the computer that is sharing the Internet connection. If you use ICS, you must enable Windows Firewall on the same connection, or you must use a third-party software firewall application.

![]() To learn more about NAT, see “NAT and Internet Connection Sharing,” p. 416.

To learn more about NAT, see “NAT and Internet Connection Sharing,” p. 416.

You learned how to configure Windows Internet Connection Sharing in Chapter 19, “Connecting Your Network to the Internet,” so we won’t repeat that information here.

If you have built a network with another type of router or connection-sharing device, you must follow the manufacturer’s instructions or get help from your ISP to set it up.

Using Add-on Firewall Products for Windows

Commercial products called personal firewalls are designed for use on PCs. These types of products—Norton Internet Security (www.symantec.com), for instance—range in price from free to about $80. Now that Windows includes an integral firewall, and Microsoft offers a free antivirus program, add-on products might no longer be necessary, and I personally don’t think that it’s worth paying for a software firewall program alone. Windows Firewall is good enough, it’s free, and it’s built in. It’s far more important that you keep Windows and all of your add-on applications up to date, and use Windows Security Essentials or a third-party antivirus/antispyware program. On the other hand, some of the third-party firewalls do monitor outgoing Internet connections, and this can let them detect a virus that slipped by an antivirus program, due to the virus’s activity. That’s pretty cool.

Securing Your Router

If you use a router for your Internet connection and rely on it to provide network protection, you must make it require a secure password. If your router doesn’t require a password, anyone can connect to it across the Internet and delete the filters you’ve set up. (As configured by the manufacturers and ISPs, connection-sharing routers are set up with the same password. Usually, it’s password. On the plus side, they typically won’t accept configuration commands from the Internet, but only from your own network.)

To lock down your router, you have to follow procedures for your specific router. You’ll want to do the following:

![]() Change the router’s administrative password to a combination of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and punctuation. Be sure to write it down somewhere, and keep it in a secure place. (I usually write the password on a sticky label and attach it to the bottom of the router.)

Change the router’s administrative password to a combination of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and punctuation. Be sure to write it down somewhere, and keep it in a secure place. (I usually write the password on a sticky label and attach it to the bottom of the router.)

![]() If the router supports the SNMP protocol, change the read-only and read-write community names (which are, in effect, passwords) to a secret word or a very long random string of random characters; or better yet, prohibit write access via SNMP or disable SNMP entirely.

If the router supports the SNMP protocol, change the read-only and read-write community names (which are, in effect, passwords) to a secret word or a very long random string of random characters; or better yet, prohibit write access via SNMP or disable SNMP entirely.

![]() If the router supports the Telnet protocol, change all Telnet login passwords, whether administrative or informational.

If the router supports the Telnet protocol, change all Telnet login passwords, whether administrative or informational.

If your ISP supplied your router and you change the password yourself, be sure to give the new password to your ISP.

Configuring Passwords and File Sharing

Windows 10 supports password-protected and passwordless file sharing. Before we explain this, we need to give you some background. In the original Windows NT workgroup network security model, when you attempted to use a network resource shared by another computer, Windows would see if your username and password matched an account on that remote computer. One of four things would happen:

![]() If the username and password exactly matched an account defined on the remote computer, you got that user’s privileges on the remote machine for reading and writing files.

If the username and password exactly matched an account defined on the remote computer, you got that user’s privileges on the remote machine for reading and writing files.

![]() If the username matched but the password didn’t, you were prompted to enter the correct password.

If the username matched but the password didn’t, you were prompted to enter the correct password.

![]() If the username didn’t match any predefined account, or if you failed to supply the correct password, you got the privileges accorded to the Guest account, if the Guest account was enabled.

If the username didn’t match any predefined account, or if you failed to supply the correct password, you got the privileges accorded to the Guest account, if the Guest account was enabled.

![]() If the Guest account was disabled—and it usually was—you were denied access.

If the Guest account was disabled—and it usually was—you were denied access.

The problem with this system is that it required you to create user accounts on each computer you wanted to reach over the network. Multiply, say, five users by five computers, and you had 25 user accounts to configure. What a pain! (People pay big bucks for a Windows Server–based domain network to eliminate this very hassle.) Because it was so much trouble, people usually enabled the Guest account.

![]() Note

Note

When you disable Password Protected Sharing, you get what was called Simple File Sharing on Windows XP, but with a twist: On XP, when Simple File Sharing was in effect, every network accessed shared resources using the Guest account, no matter what username and password were supplied. On Windows 7 through 10, if the remote user’s username matches a user account and the account has a password set, he’ll be able to access the shared resources using that account’s privileges. The Guest account is used only when the remote user’s account doesn’t match one on the Windows computer, or if the matching account has no password.

If your computer is a member of a Windows domain network, you cannot disable Password Protected Sharing.

Windows 7, 8, 8.1, and 10 have a feature called the HomeGroup that provides a way around the headaches of managing lots of user accounts and passwords. When you make a computer a member of a homegroup, it uses a built-in user account named HomeGroupUser$ when it accesses shared resources on other computers in the group. The member computers all have this same account name set up, with the same password (which is derived from the homegroup’s password in some way), so that all member computers can use any shared resource. When you share a library, folder, or printer with the homegroup, Windows gives the user account HomeGroupUser$ permission to read or to read/write the files in that folder. It’s a simple, convenient scheme, but only computers with these newer versions of Windows computers can take advantage of it.

Another way to avoid password headaches is to entirely disable the use of passwords for network resources. If you disable Password Protected Sharing, the contents of the Public folder and all other shared folders are accessible to everyone on the network, even if they don’t have a user account and password on your computer, and regardless of the operating system they’re using. This is ideal if you want to share everything in your Public folder and do not need to set sharing permissions for individuals.

From a security perspective, only a few folders are accessible when Password Protected Sharing is disabled, and although anybody with access to the network can access them, the damage an intruder can do is limited to stealing or modifying just the files in a few folders that are known to be public.

If you do disable Password Protected Sharing, it’s crucial that you have a firewall in place. Otherwise, everyone on the Internet will have the same rights in your shared folders as you.

By default, Windows 10 has Password Protected Sharing enabled, which limits access to the Public folder and all other shared folders to users with a user account and password on your computer, or to member computers in a homegroup.

If you want to make the Public folder accessible to everyone on your network without having to create for each person an account on every computer, you have four choices:

![]() If you are on a home or small office network and you have only (or mostly) Windows 7, 8, 8.1, and 10 computers, you can enable the HomeGroup networking feature, as discussed in Chapter 18, “Creating a Windows Network.”

If you are on a home or small office network and you have only (or mostly) Windows 7, 8, 8.1, and 10 computers, you can enable the HomeGroup networking feature, as discussed in Chapter 18, “Creating a Windows Network.”

![]() You can set up accounts for every user on your computer, so that they all will access the shared folder using their own account. You’ll need to be sure that all users use the same password for their account on every computer.

You can set up accounts for every user on your computer, so that they all will access the shared folder using their own account. You’ll need to be sure that all users use the same password for their account on every computer.

![]() You can create a special user account, for example, named “share,” and give people you trust the password to this account. Everyone can use this same username and password to access the shared folder on your computer.

You can create a special user account, for example, named “share,” and give people you trust the password to this account. Everyone can use this same username and password to access the shared folder on your computer.

![]() You can disable Password Protected Sharing. To do this, right-click the network icon at the right end of the taskbar and select Open Network and Sharing Center. (Alternatively, open File Explorer, select Network at the left, and click Properties in the ribbon.)

You can disable Password Protected Sharing. To do this, right-click the network icon at the right end of the taskbar and select Open Network and Sharing Center. (Alternatively, open File Explorer, select Network at the left, and click Properties in the ribbon.)

Select Change Advanced Sharing Settings. Scroll down, and under All Networks, locate Password Protected Sharing. Click Turn Off Password Protected Sharing, and then click Save Changes.

Setting Up Restrictive Access Controls

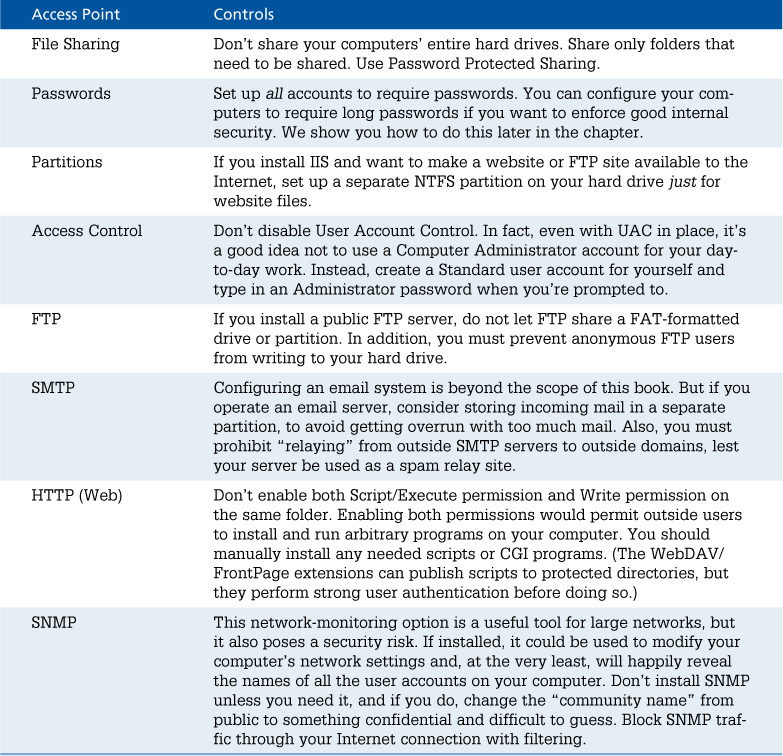

Possibly the most important and difficult step you can take is to limit access to shared files, folders, and printers. You can use the guidelines shown in Table 33.2 to help organize a security review of every machine on your network.

Testing, Logging, and Monitoring

Testing, logging, and monitoring involve testing your defense strategies and detecting breaches. It’s tedious, but who would you rather have be the first to find out that your system is hackable: you or “them”? Your testing steps should include these:

![]() Testing your defenses before you connect to the Internet

Testing your defenses before you connect to the Internet

![]() Detecting and recording suspicious activity on the network and in application software

Detecting and recording suspicious activity on the network and in application software

You can’t second-guess what 100 million potential “visitors” might do to your computer or network, but you should at least be sure that all your roadblocks stop the traffic you were expecting them to stop.

Testing Your Defenses

Some companies hire expert hackers to attempt to break into their networks. You can do this, too, or you can try to be your own hacker. Before you connect to the Internet, and periodically thereafter, try to break into your own system. Find its weaknesses.

![]() Note

Note

If you’re on a corporate network, contact your network manager before trying this. If your company uses intrusion monitoring, this probe might set off alarms and get you in hot water.

Go through each of your defenses and each of the security policy changes you made, and try each of the things you thought they should prevent.

First, connect to the Internet, visit www.grc.com, and view the ShieldsUP page. (Its author, Steve Gibson, is a very bright guy and has lots of interesting things to say, but be forewarned that some of it is a bit hyperbolic.) This website attempts to connect to Microsoft Networking and TCP/IP services on your computer to see whether any are accessible from the outside world. This is a great tool! Click the File Sharing and Common Ports buttons to see whether this testing system exposes any vulnerabilities. Don’t worry if the only test your computer fails is the ping test. If you have an Internet router or use Internet Connecting Sharing, try the UPnP test.

As a second test, find out what your public IP address is. An easy way to find out is to open www.whatismyip.com in Internet Explorer. Then enlist the help of a friend or go to a computer that is not on your site but connected to the Internet some other way. Open File Explorer (not Internet Explorer) and, in the Address box, type \1.2.3.4, but in place of 1.2.3.4, type the IP address that you recorded earlier. This attempts to connect to your computer for file sharing. You should not be able to see any shared folders, and you shouldn’t even be prompted for a username and/or password. If you have more than one public IP address, test all of them.

If you have installed a web or FTP server, attempt to view any protected pages without using the correct username or password. With FTP, try using the login name anonymous and the password guest. Try to copy files to the FTP site while connected as anonymous—you shouldn’t be able to.

Use network-testing utilities to attempt to connect to any other of the network services you think you have blocked, such as SNMP.

Attempt to use Telnet to connect to your router, if you have one. If you are prompted for a login, try the factory default login name and password listed in the router’s manual. If you’ve blocked Telnet with a packet filter setting, you should not be prompted for a password. If you are prompted, be sure the factory default password does not work, because you should have changed it.

More advanced port-scanning tools are available to perform many of these tests automatically. We caution you to use these sorts of tools in addition to, not instead of, the other tests listed here.

Monitoring Suspicious Activity

If you use Windows Firewall, you can configure it to keep a record of rejected connection attempts. Here’s how:

1. Sign in using an Administrator account, and in the taskbar’s search box type firewall.

2. In the search results, select Windows Firewall; then select Advanced Settings.

3. Under Action, select Properties. Select one of the available profile tabs (Private Profile, in most cases) and click the Customize button within the Logging area. Set Log Dropped Packets to Yes; then click OK.

4. Take note of the location of the log file, and then click OK. By default, the log file is windowssystem32LogFilesFirewallpfirewall.log.

You can enable this setting for all profiles if you wish. Inspect the log file periodically by viewing it with Notepad.

Disaster Planning: Preparing for Recovery After an Attack

Disaster planning should be a key part of your security strategy. The old saying “Hope for the best and prepare for the worst” certainly applies to network security. Murphy’s Law predicts that if you don’t have a way to recover from a network or security disaster, you’ll soon need one. If you’re prepared, you can recover quickly and may even be able to learn something useful from the experience. Here are some suggestions to help you prepare for the worst:

![]() Make permanent, archived “baseline” backups of exposed computers before they’re connected to the Internet and anytime system software is changed.

Make permanent, archived “baseline” backups of exposed computers before they’re connected to the Internet and anytime system software is changed.

![]() Make frequent backups once online.

Make frequent backups once online.

![]() Prepare written, thorough, and tested computer restore procedures.

Prepare written, thorough, and tested computer restore procedures.

![]() Write and maintain documentation of your software and network configuration.

Write and maintain documentation of your software and network configuration.

![]() Prepare an incident plan. Think through what you’d have to do to cut off Internet access, and then restore your computers and servers, and write it all down step by step.

Prepare an incident plan. Think through what you’d have to do to cut off Internet access, and then restore your computers and servers, and write it all down step by step.

A little planning now will go a long way toward helping you through this situation. The key is having a good backup of all critical software. Each of the points discussed in the preceding list is covered in more detail in the following sections.

Making a Baseline Backup Before You Go Online

You should make a permanent “baseline” backup of your computer before you connect with the Internet for the first time so that you know it doesn’t have any virus infections. Make this backup onto a removable disk or tape that can be kept separate from your computer, and keep this backup permanently. You can use it as a starting point for recovery if your system is compromised.

![]() To learn more about making backups, see “Creating a System Image Backup,” p. 750.

To learn more about making backups, see “Creating a System Image Backup,” p. 750.

Making Frequent Backups When You’re Online

We hate to sound like a broken record on this point, but you should have a backup plan and stick to it. Make backups at some sensible interval and always after a session of extensive or significant changes (for example, after installing new software or adding users). In a business setting, you might want to have your backup program schedule a backup every day automatically. (You do have to remember to change the backup media, even if the backups are automatic.) In a business setting, backup media should be rotated offsite to prevent against loss from theft or fire. You may want to do this even for home backups: Take an external hard drive or DVD backup to a friend’s house for safekeeping.

Online backup services such as Carbonite and SOS Online Backup are fantastic tools. They usually don’t back up Windows and applications, but they do frequently back up your personal files. But although cloud-based backup is an incredibly useful and valuable tool, don’t count on it alone. It can protect you from data loss due to fire or equipment failure; however, a thief who cracks your password may well delete all your backed-up data. Keep a physical backup somewhere, too.

Writing and Testing Server Restore Procedures

We can tell you from personal experience that the only feeling more sickening than losing your system is finding out that the backups you’ve been diligently making are unreadable. Whatever your backup scheme is, be sure it works!

This step is difficult to take, but we urge you to try to completely rebuild a system after an imaginary break-in or disk failure. Use a sacrificial computer, of course, not your main computer, and allow yourself a whole day for this exercise. Go through all the steps: reformat hard disks, reinstall Windows or use the image feature, reinstall backup software (if you use a third-party product), and restore the most recent backups. You will find this a very enlightening experience, well worth the cost in time and effort. Finding the problem with your system before you need the backup is much better than finding it afterward.

Also be sure to document the whole restoration process so that you can repeat it later. After a disaster, you’ll be under considerable stress, so you might forget a step or make a mistake. Having a clear, written, tested procedure goes a long way toward making the recovery process easier and more likely to succeed.

Writing and Maintaining Documentation

It’s in your own best interest to maintain a log of all software installed on your computers, along with software settings, hardware types and settings, configuration choices, network address information, and so on. (Do you vaguely remember some sort of ordeal after AT&T replaced your wireless router last year? How did you resolve that problem, anyway?)

![]() Tip

Tip

Windows has no utilities to print the configuration settings for software and network systems. You can use Alt+PrntScrn to record the configurations for each program and network component and then paste the images into WordPad or Microsoft Word.

In businesses, this information is often part of the “oral tradition,” but a written record is an important insurance policy against loss due to memory lapses or personnel changes. Record all installation and configuration details.

Then print a copy of this documentation so you’ll be able to refer to it if your computer crashes.

Make a library of software DVDs and CD-ROMs, repair disks, startup disks, utility disks, backup disks, tapes, manuals, and notebooks that record your configurations and observations. Keep them together in one place and locked up, if possible.

Preparing an Incident Plan

A system crash, virus infection, or network intrusion is a highly stressful event. A written plan of action made now will help you keep a clear head when things go wrong. The actual event probably won’t go as you imagined, but at least you’ll have some good first steps to follow while you get your wits about you.

If you know a break-in has been successful, you must take immediate action. First, immediately disconnect your network from the Internet. Then find out what happened.

Unless you have an exact understanding of what happened and can fix the problem, you should clean out your system entirely. This means that you should reformat your hard drive, install Windows and all applications from CDs/DVDs or pristine disks, and make a clean start. Then you can look at recent backups to see whether you have any you know aren’t compromised, restore them, and then go on.

But most of all, have a plan. The following are some steps to include in your incident plan:

![]() Write down exactly how to properly shut down computers and servers.

Write down exactly how to properly shut down computers and servers.

![]() Make a list of people to notify, including company officials, your computer support staff, your ISP, an incident response team, your therapist, and anyone else who will be involved in dealing with the aftermath.

Make a list of people to notify, including company officials, your computer support staff, your ISP, an incident response team, your therapist, and anyone else who will be involved in dealing with the aftermath.

![]() If you had a hacker break-in at your business, check www.first.org to see whether you are eligible for assistance from one of the many Forum for Incident Response and Security Teams (FIRST) response teams around the world

If you had a hacker break-in at your business, check www.first.org to see whether you are eligible for assistance from one of the many Forum for Incident Response and Security Teams (FIRST) response teams around the world

Alternatively, the Computer Emergency Response Team Coordination Center (CERT-CC) might also be able to help you or at least can get information from your break-in to help protect others. Check www.cert.org.

![]() You can find a great deal of general information on effective incident response planning at www.cert.org. CERT offers training seminars, libraries, security (bug) advisories, and technical tips as well.

You can find a great deal of general information on effective incident response planning at www.cert.org. CERT offers training seminars, libraries, security (bug) advisories, and technical tips as well.

Specific Configuration Steps for Windows 10

Many of the points mentioned in this chapter so far are general, conceptual ideas that should be helpful in planning a security strategy, but perhaps not specific enough to directly implement. The following sections provide some specific instructions to tighten security on your Windows 10 computer or LAN. These instructions are for a single Windows 10 computer or a workgroup without a Windows Server. Windows Server offers more powerful and integrated security tools than are available with Windows alone (and happily for you, it’s the domain administrator’s job to set up everything).

Windows 10’s Security Features

Right out of the box, Windows 10 has better security tools built in than previous versions of Windows. If you do nothing else but let these tools do their job, you’ll be better off than most people, and certainly far better off than anyone still running Windows XP. These are the built-in security features:

![]() User Account Control—UAC makes sure that programs don’t have the ability to change important Windows settings without you giving your approval. This helps prevent virus programs from taking over your computer and disabling your computer’s other security features.

User Account Control—UAC makes sure that programs don’t have the ability to change important Windows settings without you giving your approval. This helps prevent virus programs from taking over your computer and disabling your computer’s other security features.

![]() For more details, see “User Account Control,” p. 101.

For more details, see “User Account Control,” p. 101.

![]() Protected Mode Internet Explorer—Web browsers are the primary gateway for bad software to get into your computer. You don’t even have to deliberately install the bad stuff or go to shady websites to get it; hackers take over well-known, legitimate websites and modify the sites’ pages so that just viewing them pulls virus and Trojan horse software into your computer. This risk is so great that Internet Explorer was modified to run with limited privileges and can’t, for example, store files outside a restricted set of folders, and can’t change system settings or services. The idea is that if malware does get in by exploiting an Internet Explorer flaw, it won’t, in theory, be able to do much damage. (It can impair your web browsing, though, and if you inadvertently grant malware permission to modify your system by accepting an unexpected User Account Control prompt, anything goes.)

Protected Mode Internet Explorer—Web browsers are the primary gateway for bad software to get into your computer. You don’t even have to deliberately install the bad stuff or go to shady websites to get it; hackers take over well-known, legitimate websites and modify the sites’ pages so that just viewing them pulls virus and Trojan horse software into your computer. This risk is so great that Internet Explorer was modified to run with limited privileges and can’t, for example, store files outside a restricted set of folders, and can’t change system settings or services. The idea is that if malware does get in by exploiting an Internet Explorer flaw, it won’t, in theory, be able to do much damage. (It can impair your web browsing, though, and if you inadvertently grant malware permission to modify your system by accepting an unexpected User Account Control prompt, anything goes.)

![]() For more details, see “Protected Mode: Reducing Internet Explorer’s Privileges,” p. 734.

For more details, see “Protected Mode: Reducing Internet Explorer’s Privileges,” p. 734.

![]() Microsoft Edge—Microsoft Edge improves upon Internet Explorer’s defenses by not accommodating any external plug-in software. (But, it’s a big, brand-new program, so we are sure that at least some security flaws will emerge.)

Microsoft Edge—Microsoft Edge improves upon Internet Explorer’s defenses by not accommodating any external plug-in software. (But, it’s a big, brand-new program, so we are sure that at least some security flaws will emerge.)

![]() Windows Firewall—Windows Firewall blocks other computers on the Internet from connecting to your computer.

Windows Firewall—Windows Firewall blocks other computers on the Internet from connecting to your computer.

![]() For more information, see “Windows Firewall,” p. 779.

For more information, see “Windows Firewall,” p. 779.

![]() Windows Defender—Defender is an antimalware program that scans your hard disk and monitors your Internet downloads for certain categories of malicious software. It’s preinstalled on Windows 10 in most cases. The version that comes with Windows 10 has both antivirus and antispyware capabilities, and it takes the place of the Microsoft Security Essentials program that you could download for previous versions of Windows.

Windows Defender—Defender is an antimalware program that scans your hard disk and monitors your Internet downloads for certain categories of malicious software. It’s preinstalled on Windows 10 in most cases. The version that comes with Windows 10 has both antivirus and antispyware capabilities, and it takes the place of the Microsoft Security Essentials program that you could download for previous versions of Windows.

![]() For more information, see “Making Sure Windows Defender Is Turned On,” p. 719.

For more information, see “Making Sure Windows Defender Is Turned On,” p. 719.

These features are all good at their jobs. Together, they’re even better. The best bit of security advice we can give you is this: Do not disable any of them. In particular, don’t disable UAC. If you find that any of the security features cause some problems with one of your applications, fix the problem just for that application instead of disabling the security feature outright. For example, if you have a program that doesn’t work well under UAC, use the Run As Administrator setting on that application’s shortcut to let just that program bypass UAC.

If you just follow that advice, you’ll be in pretty good shape. If you want to ratchet up your defenses another notch or two, read on.

If You Don’t Have a LAN

If you have a Windows 10 computer that connects directly to the Internet but doesn’t connect to a home or office LAN, it’s still part of a network (a really big one). You need to take only a few steps to be sure you’re safe when browsing the Internet:

![]() Enable Macro Virus Protection in your Microsoft Office applications.

Enable Macro Virus Protection in your Microsoft Office applications.

![]() Be sure that Windows Defender is turned. If your computer came with a commercial antivirus program preinstalled, when it expires, you should immediately either pay for continued service or uninstall it and then immediately install another product, such as the free Windows Defender.

Be sure that Windows Defender is turned. If your computer came with a commercial antivirus program preinstalled, when it expires, you should immediately either pay for continued service or uninstall it and then immediately install another product, such as the free Windows Defender.

![]() When you connect to the Internet, be sure to stay connected long enough for Windows Update to download needed updates.

When you connect to the Internet, be sure to stay connected long enough for Windows Update to download needed updates.

![]() Be very wary of viruses and Trojan horses in email attachments and downloaded software. Install a virus scan program, and discard unsolicited email with attachments without opening it. If you use Outlook or Windows Mail, you can disable the preview pane that automatically displays email. Several viruses have exploited this open-without-asking feature.

Be very wary of viruses and Trojan horses in email attachments and downloaded software. Install a virus scan program, and discard unsolicited email with attachments without opening it. If you use Outlook or Windows Mail, you can disable the preview pane that automatically displays email. Several viruses have exploited this open-without-asking feature.

![]() Keep all of your computers and devices up to date with Windows Update, service packs, app updates, virus scanner updates, and so on, regardless of operating system. Check for updates every couple weeks, at the very least. View http://browsercheck.qualys.com every few weeks. Enable automatic updating in any application that permits it, such as Adobe Reader and Flash viewer, Java Runtime, and so on.

Keep all of your computers and devices up to date with Windows Update, service packs, app updates, virus scanner updates, and so on, regardless of operating system. Check for updates every couple weeks, at the very least. View http://browsercheck.qualys.com every few weeks. Enable automatic updating in any application that permits it, such as Adobe Reader and Flash viewer, Java Runtime, and so on.

![]() If you use Microsoft Office or other Microsoft applications, click or touch Start, Settings, Update & Security, Advanced Options. Be sure that Give Me Updates for Other Microsoft Products is checked. This will let Windows automatically download updates and security fixes for Office as well as Windows.

If you use Microsoft Office or other Microsoft applications, click or touch Start, Settings, Update & Security, Advanced Options. Be sure that Give Me Updates for Other Microsoft Products is checked. This will let Windows automatically download updates and security fixes for Office as well as Windows.

![]() On Windows 10 Pro and Enterprise, make the Security Policy changes suggested later in this chapter under “Tightening Local Security Policy.” Local Security Policy can’t be changed on Windows 10 Home.

On Windows 10 Pro and Enterprise, make the Security Policy changes suggested later in this chapter under “Tightening Local Security Policy.” Local Security Policy can’t be changed on Windows 10 Home.

![]() Use strong passwords on each of your accounts, including the Administrator account. For all passwords, use a combination of uppercase letters and lowercase letters and numbers and punctuation; don’t use your name or other simple words.

Use strong passwords on each of your accounts, including the Administrator account. For all passwords, use a combination of uppercase letters and lowercase letters and numbers and punctuation; don’t use your name or other simple words.

![]() Be absolutely certain that Windows Firewall is enabled on a network adapter that connects to a Broadband modem and on any dial-up connection icons.

Be absolutely certain that Windows Firewall is enabled on a network adapter that connects to a Broadband modem and on any dial-up connection icons.

If You Do Have a LAN

If your computer is connected to others through a LAN, follow the suggestions from the list in the preceding section, on each computer.