Putting Yourself Into Your Work

“Would anyone other than mother care to look at this?”

—Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, The Fourteen Points of Animation, 1975

Your experiences and adventures can be grist for an animated character or story. An experience that you would like to have can also provide rich material for an animated story. Did you ever fantasize about being an animal, or being able to fly? Animation makes it possible for you to do both.

Animation means “creation of life.” Life is the animator’s reference book. You’ve met literally thousands of people in your lifetime. You have had adventures in your own home and at school, perhaps with a sister or a brother. You have had parents and real or imaginary friends. Maybe you owned a pet cat or dog. You have lived in a house, a town, a country. A story viewed through the prism of your own life experience is far more interesting than a generic construction based on formulaic relationships. “Write what you know,” the saying goes. You know yourself and your friends and family. Their personalities and qualities can be used as inspiration to bring characters to life whether the story is contemporary or set in a distant time or place.

Robert Louis Stevenson based the character of Long John Silver in Treasure Island on one of his friends. Stevenson gave the pirate character traits that opposed every one of the friend’s virtues but retained his energetic and ingratiating manner—and his wooden leg. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle based Sherlock Holmes on Joseph Bell, an acerbic and observant professor at the University of Edinburgh medical school.

Biographical elements provide a “human touch” that enables the audience to identify with and sympathize with exotic or outlandish characters. They transform simple designs into living and breathing creatures with believable problems and aspirations.

Consider the following figure of two penguins and an egg. (Figure 3-1)

[Fig. 3-1] Two penguins and an egg. Reproduced by permission of Kimberly Miner.

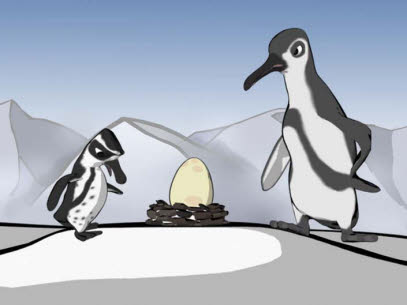

Now let us consider the same characters within a story context. Mama Penguin has charged Big Brother Penguin with the care of his (very) little brother. Big Brother would much rather go play with his friends, as shown in Figure 3-2

[Fig. 3-2] Penguin family ties. Reproduced by permission of Kimberly Miner.

Figure 3-1 shows a pair of penguins and an egg. Figure 3-2 depicts characters that relate to one another on an emotional level. The artist based the penguin children on herself and her siblings.

A good story artist utilizes life experience to give a character or story a base that an audience identifies with emotionally. This is the quality in animation that communicates across time and culture. It is not necessary to literally recreate the real-life event that inspired the story. The suggestion of humanity is what creates human interest.

Of course there are exceptions to this rule. You may want to leave out all human references to create a totally alien character or alienating environment. All stories, whether based on worldly or otherworldly rules, must sustain the interest of an audience. Even a monstrous character can inspire audience sympathy and, occasionally, empathy.

The Seven Dwarfs were not major characters in the Grimm Brothers’ original story of SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS. They were only plot motivators and did not have names. In the Disney film, the Dwarfs were each given a name that described a particular type of character. Each Dwarf reflected a different aspect of a complete human personality—not all of them good ones. Grumpy, Dopey, and Doc were more developed characters than the other four, with Grumpy being the most interesting of them all. Under the gruff exterior was a heart of gold, which he did his best to hide.

It was thought that audiences would not be able to sit for an hour to watch a feature-length cartoon. The critics would have been correct if SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS had the same story construction as many short cartoons of the period. Cartoons in the 1930s frequently resolved a simple problem with music and dance in six minutes, emphasized lovely visuals over story and characterization, or were manic outpourings of creativity and “screwy” gags relying on neither plot nor logic.

[Fig. 3-3] Many early cartoons were structured around music. Some were “moving paintings” that emphasized pretty visuals over plot.

[Fig. 3-4] The “screwball” humor of the 1930s produced manic cartoons with characters that were entertaining for six minutes but did not have the emotional range to carry a feature-length film.

Short films are vignettes. A feature film is a mural. Feature stories must hold the audience’s interest for ten times the length of a short film. It is necessary to pace the story well and alternate manic moments with sequences that allow the story to advance, and the audience to rest. We must care about what happens to the characters.

SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS is about a murder. The villainous Witch/Queen wants Snow White dead and succeeds in killing her through a trick. Fortunately, a flaw in the magic enables Snow White’s Prince to break the spell. This is the bare bones of the story.

SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS is also a love story, but the love interest—the Prince—is off screen for most of the picture. Originally he had a much larger role, but the more interesting Dwarfs and animals carry the bulk of the film’s action. Sequences in the film are well-paced and evenly divided between comedy and drama. The famous dance party at the Dwarfs’ cottage immediately follows the Witch’s creation of the poisoned apple that will kill Snow White. After the dance Snow White sings “Some Day My Prince Will Come” as the Dwarfs and animals listen. We see and hear what the girl has to live for and know that all is about to be taken away from her. This knowledge adds poignancy to the song. The three consecutive sequences neatly encapsulate the film’s entire plot and show the characters’ personalities and relationships even when viewed separately from the rest of the film.

The Use of Symbolic Animals and Objects

Animals have been used for millennia to symbolize human foibles. Most animal symbols in Western culture come from the fables of Aesop and La Fontaine and from medieval morality plays. Animal characters may be designed with human traits (Figure 3-5a). Human characters may display animal characteristics (Figure 3-5b).

[Fig. 3-5] (a) Grace Drayton’s dreaming kitten from 1921 has babyish features common to infant humans and animals. (Nancy Beiman collection) The girl in Figure (b) has a distinctly cat-like air. Reproduced by permission of John McCartney.

“The Great Roe is a mythological beast with the head of a lion and the body of a lion, but not the same lion.”

—Woody Allen

Here is a list of animals and their symbolic meanings. Some animals have been used to represent more than one human trait and opposing traits are sometimes represented by the same animal.

- Lion (brave, dignified, the King of the Beasts)

- Lamb (meek, mild, innocent)

- Mouse (timid and defenseless)

- Rabbit (clever and resourceful or timid and defenseless)

- Bear (brute strength, brawn without brain)

- Cow and sheep (unintelligent, docile, a follower)

- Cat (sly, cruel, deceptive, and self-centered)

- Dog (loyal and brave or a fawning servant)

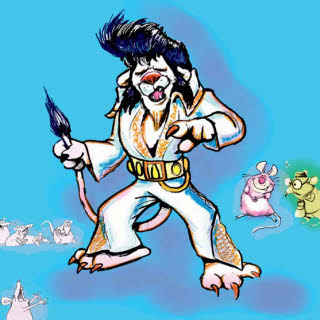

[Fig. 3-6] Symbolic Beasts. The viewer responds subconsciously to these cultural references, presuming that the lion is brave and the mouse is timid. What if roles were reversed so that the lion was timid and the mouse brave? The lion’s outfit also displays symbolic meaning. The use of contrasting symbols creates a visual pun.

I illustrated a children’s book for Patricia Bernard, the well known Australian author. Basil Bigboots the Pirate was originally about human pirates from the four corners of the earth who needed to find a ‘pirate shop’ selling new clothes to replace their torn finery. I suggested the story might be more entertaining if we used animals instead of people to represent the different nationalities. The animals would look funny wearing human clothes, whether torn or whole. Patricia thought this was a good idea and changed her story accordingly. Basil was easy to cast as a British Bulldog. His boots and his ego were big but the rest of him was very small. (Figure 3-7)

[Fig. 3-7] Captain Basil Bigboots, the British Bulldog Pirate. Illustration by Nancy Beiman, reproduced by permission of Patricia Bernard.

Which creatures would best represent pirates from South America, Africa, and China? We quickly settled on a parrot and a gorilla for the first two countries’ symbolic animals. I then drew thumbnails of a Chinese dragon pirate. Patricia suggested that a panda would be a much better choice, and she was right. The panda has black circles around its eyes that suggest eye patches. This creates a visual pun.

Patricia added an American character after I drew up this sketch of Boston Bertie, the ‘wildcat’ dealer in secondhand pirate ships. (Figure 3-9)

[Fig. 3-8] Chinese pirate from Basil Bigboots the Pirate. Illustration by Nancy Beiman, reproduced by permission of Patricia Bernard.

[Fig. 3-9] Would you buy a used pirate ship from Boston Bertie? Illustration by Nancy Beiman, reproduced by permission of Patricia Bernard.

A “story map” was created for the book before it was written. Story maps can be of a town or country or of an entire planet. These need not be complex drawings. A simple square with circles or boxes labeled with the elements of the story is quite sufficient. Everything on the story map should be relevant to the story and should be used in the story. In Basil’s case, the map was a very literal one. The pirates travel to the four quarters of the compass in search of their shop. North America was not originally on the story map and so it only existed in Basil’s universe after Patricia added Boston Bertie to the story. The final tale was completely different from the one we started out with, and we had a lot of fun changing it!

It’s much easier to change things at the beginning of the production than when you are halfway through. Be open to alternative views when developing a story idea and characters. It is fun, it’s creative, and it leads to better storytelling.

“I AM A ROCK, I AM AN ISLAND.”

—Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, I Am a Rock

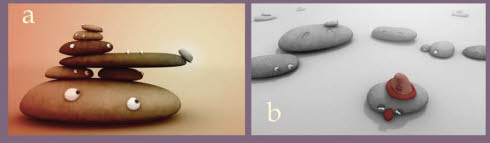

One definition of animation is “the act of infusing life.” Objects that are inanimate in the real world can come to life in your imaginary one and become symbolic or actual personalities. For example, a rock can be used to portray strength, solidity, or immobility. It conveys a different meaning altogether when it shatters through stress or is worn down into sand by the actions of wind and water.

The animation medium superbly conveys abstract concepts and emotions through symbolic objects and colors with the added dimension of movement over time. An “invulnerable” rock may be emotionally fragile. Water and rivers symbolize life, yet they become menacing when they flood. A cloud can be a fleecy impermanent thing or a terrifying storm. In animation, a tree is never just a tree—it may be your leading lady!

[Fig. 3-10] The abstract concept of danger (a) and humor (b) is illustrated graphically with rocks contrasting physical permanence with emotional variability. Animation brings life to allegorical symbols and colors. Reproduced by permission of Joseph Daniels.

A man holding a club conveys a very different meaning than a man holding a baseball bat even though the two objects are roughly the same size and shape and are used to hit things. An object’s meaning varies with its context.

Suitable props will add dimension and depth to your character animation. Symbolic shapes also convey meaning to your audience. These are discussed in Chapter 6. The emotional use of color is discussed in Chapter 17.

The Newsman’s Guide: Who, What, When, Where, and Why

Exercise: Design four cats.

Do not start drawing right away. Think about the assignment carefully. What information have you been given? What information is missing? A story artist or character designer will ask for more background about these cats before working on designs.

Who are they? What are they? Where do they live? When does the action take place? Why do they do what they do and who or what do they interact with?

If you do not ask these questions, you may still design good cats, but they will be designs, not characters.

[Fig. 3-11] Four cats. The designs are graphically interesting but individual characters have not been defined. Reproduced by permission of Nina L. Haley.

Now try the assignment again, using the following information: Mama, a very proper and dignified cat, has three kittens. A story begins when you flesh out the original description of “four cats.”

Now explore the characters. Are they “real” cats? Do they have human qualities or are they pure animal? Make a list of props that they could interact with. Where do they live? Which locations and props offer the best possibilities for animation? You can experiment with the scale of the mother cat to her kittens, as shown in Figure 3-12.

[Fig. 3-12] Kittens will have very different proportions from their mother. Body shape and agility will vary with age. Reproduced by permission of Nina L. Haley.

Now do a few small drawings (thumbnails) of the cats working with some of the props and write short sentences under the drawings describing how the situation might develop. Do not cross out any of the drawings and do not throw any of them away. At this stage, you should be open to all suggestions, no matter how crazy they may sound. You may sketch new ideas that will create a story, or take an existing story in a different direction.

How do you turn generic cats, rocks, or trees into individual characters? You could use human beings as a reference for their personalities. Start with the basics. Here’s where your life experience literally comes into the picture.

Exercise: Sketch two human characters based on yourself and a friend at five years of age. Change the two humans into cats, translating the humans’ attitudes and expressions to the cats’ faces and bodies. Next, turn the humans into objects that portray their personality types. Experiment with the shape and scale of three different objects.

You know your own personality and that of your friend. How do you translate this quality into a character design, especially a nonhuman one? You can base the designs on caricatures but that is not always necessary.

By just thinking about the pets, friends, and people you have met while you are working, you will subconsciously start to incorporate some of their mannerisms and appearances into your design and story. This will make the characters uniquely yours and not a mere imitation of a style. No two people have precisely the same experiences in life. Referring to your own memory bank will keep your designs and stories fresh.

“You see, but you do not observe.”

—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Sherlock Holmes), A Scandal in Bohemia

Observe life with the artist’s eye. Notice everything. Draw it in your sketchbook. You will not only have an endless source of reference for animation, you will never be bored!

Interesting drawings of human relationships and motion can be done while waiting in an airport or train station or launderette. Attend horse, cat, and dog shows and county fairs. Visit zoos and children’s playgrounds. Draw in your sketchbook every day. Any situation or location becomes interesting if you observe and analyze how living creatures move and react. There is no such thing as a dull location—there is only the lack of perception of the extraordinary variety in life. Everything becomes interesting when you view it with the artist’s eye.

[Fig. 3-13] There is no such thing as an ordinary location. Interesting gesture drawings can be done at home, a supermarket, or a playground.

Do not copy other animated films. It is too easy to be caught up in a style and imitate it so that the style is emphasized over the substance of your project. You will be looking through another animator’s eyes and creating a pale imitation of their references and experiences.

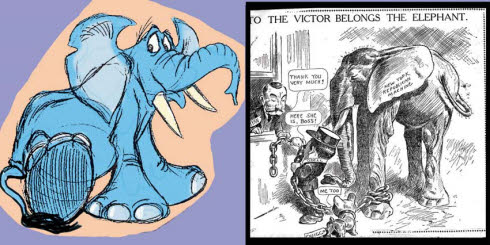

Familiarize yourself with the work of the great artists and cartoonists of earlier times. Am I contradicting myself? No, because there are so many more cartoonists and illustrators than there are animators. Animation is a little more than a century old. Cartoon art is 500 years old and graphic art is over 40,000 years old. Drawing inspiration from unusual source materials will help you design characters that are graphically interesting and original. Figure 3-14 shows how I used a classic cartoonist’s work as inspiration for one of my own characters.

[Fig. 3-14] “Harry” from the film Your Feet’s Too Big (1984) by Nancy Beiman, and Republican Elephant by T. S. Sullivant (1904). I based my character design on Sullivant’s cartoons such as the one shown here. (Nancy Beiman collection.)

Be sure to always put a bit of yourself into your work. It is true that there are no new stories. There are only stories and characters that you have not done before. Your interpretations of the material will make it your own. Never copy anything outright. Put your source aside after a while and use your imagination to elaborate on it. The resultant mix will lead to original creation.

Do not forget to consider character relationships from the very start. Emotional relationships can develop over time, but their base remains consistent. (The penguin mama and children in Figure 3-2 will always have the same relationship to one another.)

You’ve now considered themes from a variety of sources and are ready to start developing situations and characters. Two approaches to story development are discussed in Chapter 4.