4

Getting Comfortable with Adaptation: The Slowest Rate of Change Is Happening Now

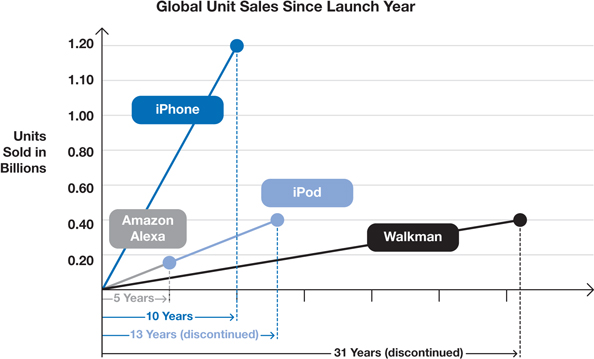

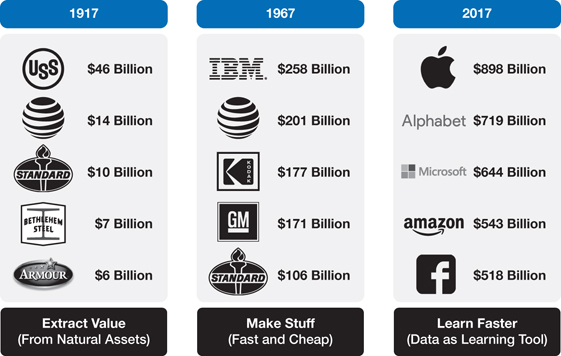

Key Ideas Stop. Breathe. Inhale deeply. Exhale slowly. Take a moment to experience slowness. Pause. As author and business strategist Dov Seidman says, “When you press the pause button on a computer, it stops. But when you press the pause button on a human being, it starts. It starts to rethink, reimagine, reflect.” This is our unique, human, competitive advantage. Feel refreshed? Great. Now get ready to leap into action. The speed with which technological, cultural, and social changes come at us is only accelerating. This exact moment in time, right now, is the slowest rate of change you will experience ever again. This speed of change makes it even more important to occasionally pause to reflect and focus on being human. Advances in technology allow machines to do many things, but they cannot dream, contemplate, or yet imagine our unseen future. Both the acceleration in change and the need to pause may seem like frightening propositions to some. We, however, think this just might be the start of the most exciting ride of our lives. Why the optimism? Because the antidote to speed isn't slowness; it's learning and adapting. Do you remember what it was like to pack your lunch and get ready for the first days of a new school year? Those were exciting times in our childhood. Most everything about the days ahead was up in the air. Would we like the new teacher? Who would be in our class? What new subjects would be on the syllabus? Sure, there was anxiety, but there was also this one clear fact: the start of a new year was a clean slate. Imagine what it might be like to tackle each workday as if it were the first day of school, but without the starchy new clothes. That idea—that every day is a new learning day—is at the heart of the adaptation advantage. Individuals and organizations best able to take in new data, read a situation, and pivot to a new opportunity are the ones best prepared to respond to—and even embrace—continuous change. And here's the interesting thing: the same forces that are changing work as we know it are also providing the technology to help deal with that change. “Because we now have more access to data, and the ability to do more advanced workforce analytics, we tell someone where they can pivot to or what roles have good adjacency,” says Joanna Daly, vice president of human resources at IBM. “We can deliver learning plans using automated recommendations. We have a digital learning platform, very Netflix-like. The technology five or six years ago might not have been there to run that kind of platform. So while on the one hand forces are at play creating the need for a much more agile learning culture, some of those same forces technologies are giving us the answer of how to respond.” Management consultant John Hagel, co-chairman for Deloitte LLP's Center for the Edge, called this kind of continuous adaptation “scalable learning.” Throughout history, industrial companies grew and thrived by embracing scalable efficiency. Essentially, once a company figured out how to make something of value, it leveraged technology and process innovation to deliver the product more quickly and less expensively in order to make more profit. This model of scalable efficiency works well in an analog world where a company's performance is determined by how profitably it can deliver a product to more customers. That model breaks in the digital era, however. Digital production at scale is virtually infinite and incremental costs are virtually zero. That's the upside. The downside is that products—digital and digitally enabled—have shorter life cycles than they once did. Consider the Sony Walkman, introduced to the market in 1979. For its time, the Walkman was an innovative personal, portable music machine. For the next 30 years, Sony continuously innovated the product line, altering styles and media from cassettes to compact discs to keep pace with fashion and technology innovation, ultimately selling 385 million units before discontinuing the Walkman brand in 2010.1 By contrast, Apple introduced the iPod in 2001 and sold virtually the same volume—390 million units—before ending most production in 2014 (Figure 4.1). While the iPod Touch remains a product in the Apple lineup, it is a fraction what it was in the company's portfolio when the iPod held three or four spots in Apple's product lineup at once (Classic, Mini/Nano, Shuffle, Touch). Like Sony, Apple innovated iPod styling and capabilities, releasing new hardware models annually and software updates regularly, but despite these updates the market moved beyond a single-purpose personal media player and ended the iPod life cycle in less than half the time that Walkman products were in the market.2 What killed the iPod? The iPhone. Apple killed its iPod cash cow in 2007 at the peak of iPod sales. The lesson here: if we disrupt ourselves at our peak, we'll be well prepared to surf the next wave of innovation and we'll own the timing of our transformation. That is the adaptation advantage in action. Figure 4.1 Speed-to-Product Peaks and Life Spans Data sources: International Data Corporation and the product manufacturers. Life spans of most digital media products are even shorter. Myspace launched in August 2003 and peaked five years later at just under 60 million users per month. Google Glass was all the rage, until it wasn't, going from darling to discontinued in just three years. RIM's early smartphone dominated the smartphone industry at the time; today, BlackBerry is little more than a footnote in the history of mobile device technology. The combined forces of social media and mobile photography enabled by smartphone cameras have all but killed the stand-alone camera business (Figure 4.2). Figure 4.2 The Rise and Fall of the Camera Data sources: The Camera and Imaging Product Association and International Data Corporation (smartphone shipments). Surely, there are many reasons that these products could not sustain their market popularity, but at the risk of overgeneralizing internal business dynamics, one factor was crucial in determining whether the companies that created these short-lived products survived the bust: their ability to learn from the market and their mistakes, adapt to new opportunities, and move on. Research from the consulting firm Innosight, published in the Harvard Business Review in 2019, found that the companies that most successfully navigated the past decade of digital transformation did so by doing three things: identifying areas for new growth through novel products or services or markets, repositioning their core business, and improving financial performance. Essentially, this is our simple formula: learn, adapt, and perform. Consider Netflix, which launched in 1997 shipping DVDs by mail; they discovered new opportunity in streaming media and repositioned their core business to streaming media by 2007. In 2011 they started creating original programs, a pivot to new content that now comprises 44% of their revenue as of 2019.3 In each of these strategic moves, Netflix flexed its adaptation advantage. With that formula in mind, let's look at the history of the world's top five leading companies by market capitalization at 50-year increments, and the past trends become very clear (Figure 4.3). Figure 4.3 Top Five Companies by Market Capitalizations at 50-Year Increments In 1917, four of the top five companies (US Steel, AT&T, Standard Oil, Bethlehem Steel, and Armour Meat Production) created value by extracting, processing, and packaging natural assets (oil, steel, meat). In 1967, four of the top five companies (IBM, AT&T, Kodak, GM, and Standard Oil) created value by optimizing the production (scalable efficiency by another name) of consumer goods. In 2017, all five of the top five companies (Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, and Facebook) were digital or digitally enabled. Technology and data makes these five companies thrive, for certain, but they are not just winning through technology. Digital technology enables flows of data, and data is an input to learning. These five companies created value by learning faster than their competition and easily adapting to new business models. Each company on this list has launched new products or services, repositioned its core business model, and continuously redefined itself. Amazon began as an online bookseller and now has reach into media, logistics, retail, grocery, and more. Every product Amazon offers is a vehicle to learn more about their customer; every interaction is a learning moment and a catalytic moment for new value creation. Every product offers feedback from customers, each and every one an input toward adaptation. This is what Hagel calls scalable learning. Writing with renowned futurist John Seely Brown for Deloitte Insights in the Spring of 2013, Hagel was among the first management gurus to recognize the need to embrace a learning mentality. As the pace of change increases, many executives focus on product and service innovations to stay afloat. However, there is a deeper and more fundamental opportunity for institutional innovation—redefining the rationale for institutions and developing new relationship architectures within and across institutions to break existing performance trade-offs and expand the realm of what is possible.

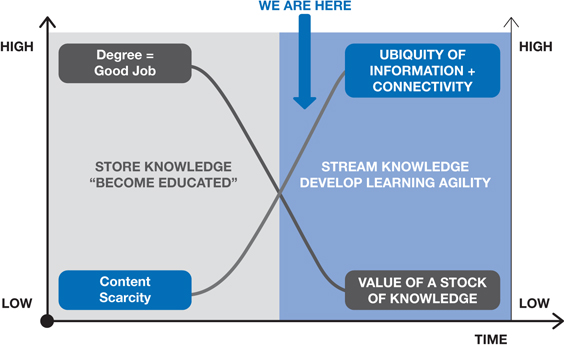

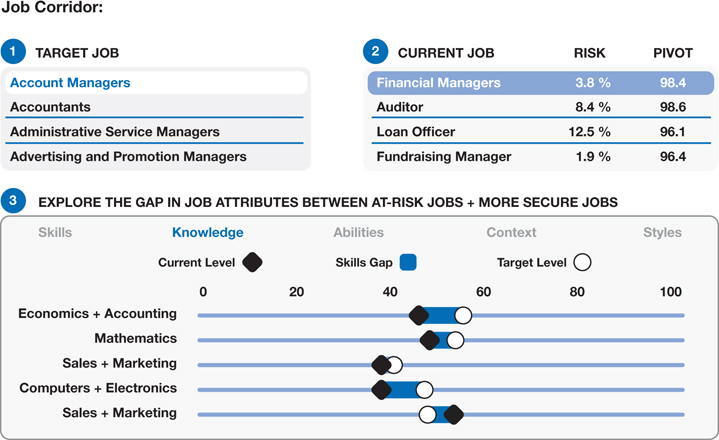

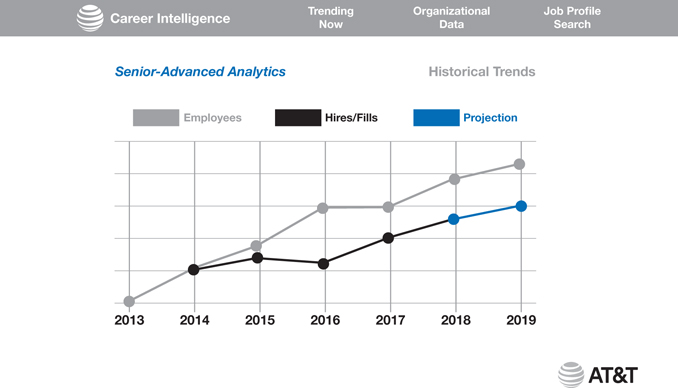

Institutional innovation requires embracing a new rationale of “scalable learning” with the goal of creating smarter institutions that can thrive in a world of exponential change.4 Scalable learning is what allows a company like Amazon to transform from online bookseller to global marketplace to web services provider to Academy Award–winning entertainment producer. Amazon seizes the opportunities that come like so much flotsam and jetsam of rapid market disruption. But scalable learning is so much more than evaluating market turns and grasping at emerging fads. Principal to scalable learning is recognizing that information, which is the atomic stuff of learning, is changing. In a slow-moving world, we had time to codify information into curriculum, establish a pedagogy, conduct training sessions, memorize, test, and apply “stocks” of knowledge, quite like inventory stored in a supply closet for future use. When we stored those precious stocks of knowledge properly, we were granted a credential and deemed “educated.” In a fast-moving world, the information comes at us not in packaged and digestible chunks but in continuous flows. To become scalable learners, we need to become adept at drinking in new information as it flows by (Figure 4.4). Figure 4.4 From Stocks of Knowledge to Flows of Knowledge Credits: John Hagel (@Jhagel) for the stocks of knowledge concept and Laurence Van Elegem for the stream knowledge concept. Once more from Hagel and Seely Brown's 2013 essay: As the pace of change accelerates, the value of any stock of knowledge depreciates faster and faster. Today, competitive advantage is not based on stocks of knowledge, but having access to flows of knowledge to enable up-to-date information that enables adaptability.5 Flows come by opening ourselves and our organizations to new sources of information. Collaboration across organizational boundaries is one way of stepping into the flow. The payment-processing company PayPal, for example, offers a training program that rotates employees through short-term tours in the company's departments and business units. Employees are expected to learn the operations of each department and, more critically, to teach their colleagues about and provide insights into the other units they've experienced. In this way, everyone gets a broader view of the company and its capabilities. This model of learning-centric expeditions is what LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman proposed in his seminal Harvard Business Review article “Tours of Duty: The New Employer-Employee Contract.”6 Cisco Systems developed CHILL, Cisco Hyper Innovation Learning Labs, to bring customers from diverse industries together to “disrupt through the development of businesses and joint projects in 48 hours.”7 In 2018, a group of companies from industries as different as office equipment and oil refining gathered in San Jose for a two-day design sprint to learn how humans and machines might work and learn together in the future by prototyping product ideas. By working across corporate boundaries and making feedback from future users a critical part of the design process, participants in the lab expanded their flow of information. “The key factor in learning by doing is to be humble enough to listen to what the end user is telling you,” says Kate O'Keeffe, director of CHILL. “People used to be interested in the innovations I was working on, and now they are far more interested in the curiosity and iterative approach that we take to get there.” Why is that? Because that's where the learning happens. Fundamental in this shift from stocks of knowledge to flows of knowledge is letting go of the idea that we learn how to work and then apply that learning to a lifelong career. This thinking worked in the slower-moving industrial era. We progressed through school picking up and storing knowledge (and, let's acknowledge it, building discipline) that was useful for working in an efficient industrial organization. Along the way, we learned a lot about a specific function like accounting or supply chain management or mechanics. From time to time, we might have even refreshed our knowledge stocks with new information, taking professional and skills development courses to make our learning current. We exercised that knowledge on the job, every day, applying what we knew to the efficient processes that made an organization effective and, hopefully, profitable. Then, at the end of a long career, we retired. Learning to work to retirement was, for most folks, a pretty straight pipeline, and for way too many, a bit like living life as a component moving on a factory conveyor belt. (Revisit the book's Introduction if you are not familiar with these concepts.) That conveyor belt not only prepared us for our jobs but also fixed our occupational identities in our minds. Work was more siloed by function and we tucked into those silos until business management gurus touted cross-functional teams and the notion of the “T-shaped” (team-based) thinker as a better alternative to the single discipline focus of the “I-shaped” (individual-based) worker. That old conveyor belt of the past was a pretty effective system when business optimized for efficiency, but it's no kind of system at all when businesses optimize for learning, which they must do now to remain relevant. Now, rather than learning how to work, we ought to work in order to learn. That is, we take learning from our work as the primary benefit of work. The products and services we create and sell deliver revenue to the company. More importantly, the individual and collective learning we take from the process of creating those products and services builds the capacity of the worker and the organization to learn, create, and produce even more. When the pace of change accelerates, the products and services we produce are evidence of our capacity and the result of our learning. Further, this velocity of change requires that we abandon the discipline identity of both the I- and T-shaped theories and move to transdisciplinary “X-shaped thinking,” wherein humans and machines collaborate from discipline-agnostic perspectives to find and frame emerging complex challenges (Figure 4.5). Working to learn requires that transdisciplinary mindset. Figure 4.5 From I to T to X: The Transdisciplinary Imperative People have always learned on the job, but what they learned was how to perform the explicit aspects of the job; they acquired the skills to do the work. Now, we have to ask what the work has taught us. What did we learn from all the information that flows through the process of working? How were specific problems solved? Which approaches failed and why? How might those same approaches be effective in different circumstances? Who contributed and how well did they work as a team? What new skills and insights were developed in the course of the work? Where might we apply this new learning elsewhere in the organization? What did performing this work teach us about ourselves, our organization, and our abilities to do more and better work together? These questions are the tip of the iceberg of intentional learning, and they all start with the core questions: In what ways are we smarter now than before we started? How have we increased our capacity as individuals and as an organization? The answers to these questions get at another how, the tacit knowledge that underpins what we do in our organizations. Tacit knowledge flows around explicit skills, and both are needed to do a job well. The same introspection that codifies workplace learning is essential for workers as they build bridges from one job to another. And it's the key to moving fast in the face of change. Rather than thinking about what you do as a job, inventory what you do in the job. That collection of capabilities and skills most certainly is widely applicable to many other, different kinds of work. Consider the case of William. For nearly 30 years, he's made a career in education, first as a classroom teacher, then school principal, until finally he was hired as the superintendent of a regional school district. Along the way, he earned a doctorate in education. “I don't know what I would do if I weren't an educator,” Will told us. Frankly, we were stunned. Across his career, Will had exercised tremendous skills through a wide array of challenges. When an elementary school caught fire over a long holiday weekend, he successfully and swiftly managed the crisis, shifting hundreds of kids, teachers, bus schedules, and school staff to other locations and communicating complex logistics, so that students would not miss a beat when schools returned to session. When teachers went on strike, he negotiated the contentious relationship between the union and the school board, bringing everyone to the bargaining table and ultimately to agreement. He has overseen construction projects, mentored student teachers, managed public relations, and much more. Any of these skills are transferable to hundreds of jobs that would never have “educator” in the job description. But because Will attaches his professional identity to a singular kind of work, he fails to see that his pattern of experience might match that required for some other type of work. Will is not alone. And this need to overcome the fixed occupational identity has created an opportunity for Michael Priddis, the CEO of Faethm.ai. Calling itself the “world's data source for the Fourth Industrial Revolution,” Faethm has developed a software platform that uses payroll and HR records to analyze a company's workforce and, using predictive analytics and market data, identify opportunities to optimize through automation. Make no mistake, this optimization comes at the price of jobs. Automation of current work reduces headcount. But this foresight is a lot like fire: it can burn our homes down, but it also can cook our food and heat our homes. So Faethm's software also provides another, human-centric, view: it identifies opportunities to proactively upskill and reskill for the workers whose jobs are most at risk. Specifically, the platform can recognize which workers will be affected, and—most importantly—match those workers’ skills to other needed roles within the organization. According to Faethm, the software calculates a “pivot score” that identifies the jobs that match an employee's capabilities and ranks them by the quality of the move, considering pay, location, and the shortest possible learning pathway (Figure 4.6). Figure 4.6 The Job Corridor and Pivot Score For example, a bank might be shedding accountant jobs in favor of automation, yet that same bank may need to staff up on cybersecurity analysts. “The skill gap between the two is small,” Priddis says. “The gap isn't a process gap, but a knowledge gap. The abilities and activities are almost the same, so you are really mostly retraining on domain knowledge.” By matching patterns, the Faethm software creates a “job corridor” from one role to another within the company, avoiding the expense and delays that are associated with the “spill and fill” approach to workforce management—laying off employees whose jobs are no longer needed and hiring new employees for newly created roles. Ironically, perhaps, because AI is often the basis of many job-disrupting technologies, this particular AI system is helping workers move to new jobs when technology takes the ones they currently have. You don't need to be a highly tuned AI system to become an agile and adaptive pattern matcher, however. You simply need to think about your work more broadly than the narrow description that defines your occupational identity. What have you learned that gives you access to new opportunities? A study by Willis Towers Watson found that 90% of maturing companies expect digital disruption, but only 44% are adequately preparing for it. AT&T saw changes coming to its business more than a decade ago when they realized that at least 100,000 of their 250,000 employees were in jobs that were unlikely to exist a decade later. They calculated that the median cost of replacing an employee was 21% of their salary and decided to take a different path. Those 100,000 people may have lacked the explicit knowledge in the skill areas of new positions, but they had tremendous tacit knowledge about the organization that would be hard to replicate. AT&T invested $1 billion in a massive learning infrastructure they called “Future Ready” with a companion employee guide called “Career Intelligence.” Each employee can view the career intelligence dashboard that shows available jobs, required skills, salary range, and, most importantly, the job demand outlook—how long that job is expected to last. The company is explicit with employees that reskilling (learning new skills) or upskilling (going deeper on current skills) is not a one-time event but a continuous journey.8 We spoke with Bill Blasé, senior executive vice president of human resources, about why AT&T started making these considerable investments more than a decade ago. “As our company continues to evolve, we're working constantly to engage and reskill our employees, and to inspire a culture of continuous learning,” he told us. “It's the right thing to do for many reasons, not the least of which is providing those who have helped to build AT&T an opportunity to grow and succeed along with the company. For us, the reskilling effort is about transparency and empowerment—creating learning content, tools and processes that help empower employees to take control of their own development and their own careers” (see Figure 4.7). While AT&T is not likely to retain every worker, the company's intent and process of training its existing workforce with new explicit knowledge has retained a tremendous amount of tacit knowledge, the know-how that enables the know-what. Figure 4.7 AT&T Career Intelligence Job Outlook Data source: Information courtesy of AT&T. By looking at skills and capabilities, rather than at specific jobs, much like AT&T and Faethm have done, the Foundation for Young Australians identified seven “job clusters” where common skills and capabilities are organized into a set of jobs.9 It might not be surprising to learn that in the care-giving job (the “Carers”) cluster, for example, physicians, social workers, and fitness instructors share similar sets of capabilities. Or that “Informers” such as teachers, economists, and accountants had overlapping skillsets. Hidden in that data, however, was a surprising and exciting discovery. By training for one job in a cluster, you acquire on average the skills for 13 other, different jobs. “This is profoundly important,” says the organization's CEO Jan Owen. “The fact that you could unlock up to 13 other jobs by entering into one job in a cluster changes everything. It shows you that you can move.”10 The best organizations realize that talent mobility strengthens their adaptation advantage. More importantly, Owen points out, these other jobs require relatively minor upskilling or retraining to move from one to another. You do not have to start over from scratch. In this increasingly fast-moving, change-dominated world, the speed you need comes from matching the “how,” rather than the “what,” of what you do. Make that shift in perspective and identity, and you are well on your way to adapting to the emerging market.

The Power of Pause

From Scalable Efficiency to Scalable Learning

From Stocks to Flows of Knowledge

From Learning to Work to Working to Learn Continuously

Identifying Patterns to Build Bridges

Notes