7

Learning Fast: Why an Agile Learning Mindset Is Essential

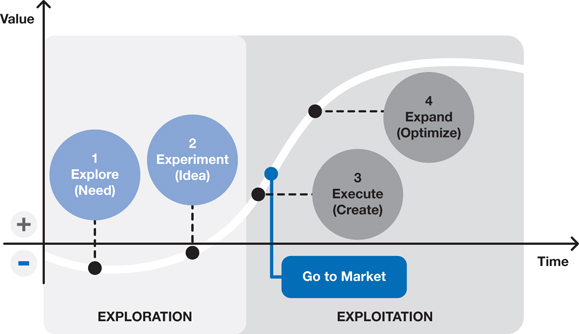

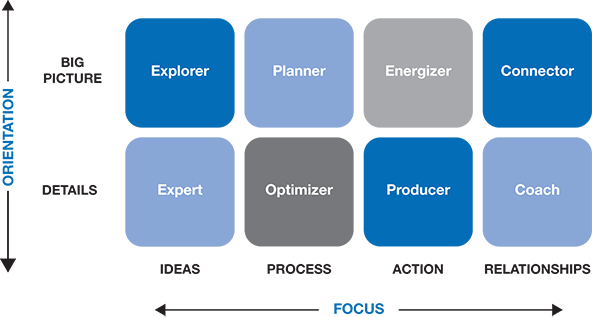

Key Ideas We are in the greatest velocity of change in human history, and somehow we've got to keep up. The thing is, we will never keep pace by doing the same things faster. In fact, that will only get us farther behind. Why? Because it is the modality of the past. To keep up with this quickening pace, we need to focus not on speed and efficiency, but on agility and adaptability. We are emerging from decades of work formed around what Deloitte's Center for the Edge founder John Hagel calls “scalable efficiency.” In this model, a company triumphed in the marketplace by making goods faster, cheaper, and overall more efficiently. They extracted the greatest value by optimizing every aspect of the production process. That method worked when business models and product lifecycles lasted a long time. Workers could perform similar tasks over longer periods of time and focus on refining their processes to improve efficiency. Not so in the digital economy we now find ourselves squarely in. Old ways of doing things are quickly becoming obsolete and sending businesses off course in a race to the future. As the New York Times's Thomas Friedman says, “When you are in accelerated change, small errors in navigation can get you off track very quickly.” It is critical, then, to remain open and attentive to the signals that recommend course corrections, lest you quickly go too far astray. What's the answer? To keep up with change, we must foster learning and adaptive organizations, ones that are able to see and interpret change as it comes at them. As Friedman notes, “The most open and connected systems allow you to get the signals first.” Those signals enable you to sense and respond to changes in technology or the market. Those signals require new learning. To understand what it means to be a learning organization, it's instructive to consider the evolution of organizational learning. Global management consulting firm Boston Consulting Group (BCG) defined “generations” of learning organizations in its 2018 paper, “Competing on the Rate of Learning.” “In first-generation learning organizations, businesses learned how to execute existing processes more efficiently—best exemplified by the ‘experience curve.’”1 In other words, first-generation learning companies acquired knowledge and stored expertise. Second-generation learning companies eye the current product life cycle and optimize for efficiency while simultaneously seeking the next product introduction. They operate in two modes of learning at once, modes we call efficiency and exploration. BCG notes that a second-generation learning company is increasingly important today because “technological innovation has compressed product life cycles, so new learning curves appear before old ones have fully played out—and firms must balance both dimensions of learning at the same time.” The third-generation learning company is the most advanced. It uses what the BCG calls the “autonomous learning loop.” In this scenario, sensors, platforms, and artificial intelligence rapidly accelerate the rates of learning by generating, gathering, and processing data in real time. In this third scenario, the company becomes self-tuning around its processes. Humans focus on complementing the technology by leveraging their uniquely human skills to add value to and make meaning from automated data processes. Regardless of how we work, we all do so within the context of a business, and a business is merely the ability to identify and solve a problem and provide a solution at scale. By this definition, every organization is a business, whether it is a for-profit corporation, a nonprofit religious or social group, a government bureaucracy, or an academic institution. A business is simply a container for work, no matter what its purpose. The process of finding that problem and solving it at scale follows a classic S-curve. The classic S-curve of any technology or business model begins with an investment in time, money, or both, then scales quickly as users adopt the offering, before leveling off as the offering reaches maturity and is replaced, ultimately, by a better solution. The S-curve is a macro process in two phases: exploration followed by exploitation or, in other words, value creation followed by value extraction. Within these two macro phases are four stages, not unlike many design thinking processes (Figure 7.1):

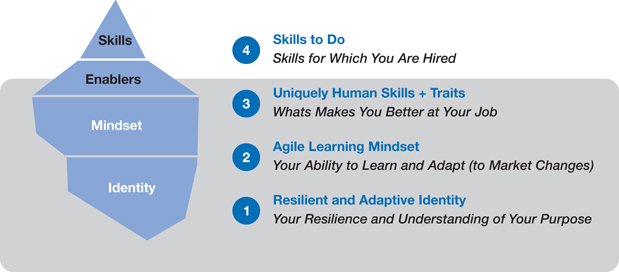

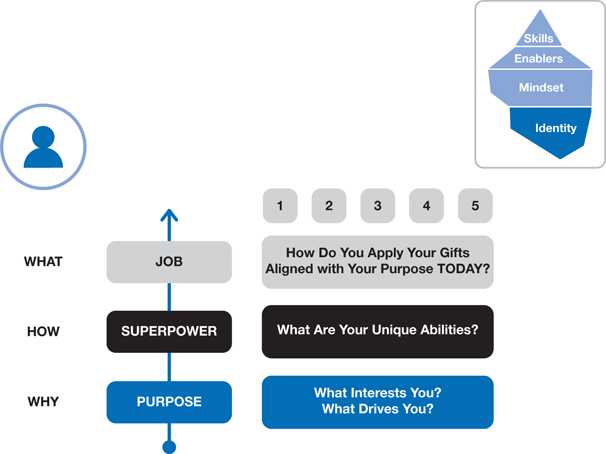

Figure 7.1 The Value Creation S-Curve: Explore, Experiment, Execute, Expand These phases are iterative and each progression from one phase to the next may circle back to check assumptions and make sure the right question is being answered by the value created. When the world was slower and products, services, and business models lasted longer, much of a company's activity lived in stages 3 (execute) and 4 (expand), during which time the product went to market. The bulk of the effort was spent creating greater efficiencies in production while driving demand through promotion. Now, because the rate of change has accelerated, the S-curves are shorter and closer together, so we must become more comfortable working in stages 1 and 2 (exploration and experimentation) (Figure 7.2). Figure 7.2 Old Economy S-Curve Gives Way to Shorter and More Frequent S Curves And there is advantage in it, too. So many skills can and will be replaced with AI, neuroscientist Dr. Vivienne Ming reminds us. “If you want something that grows, changes, explores, pushes boundaries, there's just nothing in the fields of AI that does anything like that right now,” she told us. “There's no machine learning I can build that can explore. That's the unique value proposition of humans.” That view is reinforced in BCG's third-generation “Autonomous Learning Loop” report. Product and business model lifespans shorten and technologies better address efficiency, leaving humans to look past the expertise of the exploitation phase and refocus efforts and abilities on the exploration phase of value creation. This shift has driven the popularity of Design Thinking, a set of exploratory practices that deliver deep investigation into problem understanding, user empathy, and solution matching. In recent years, Design Thinking has been a popular buzz phrase, and is often used narrowly to describe only one of several applications, such as customer-centric innovation, iterative prototyping, continuous improvement, or broad and freeform brainstorming. Design Thinking can be all of those things. Originating in industrial design, Design Thinking places the user or customer at the center as the primary focus of the product, service, or system development efforts. Design Thinking begins by looking carefully at the challenge to make sure the problem to be solved is correctly identified and understood, then framing the challenge in a way that reflects that deep understanding, and finally developing, testing, and iterating on proposed solutions. It's relatively easy to come up with new forms of existing solutions. Design Thinking comes into play when we consider the challenge the original product was created to solve. That's the difference, for example, between creating a new kind of drill bit and designing new ways to make holes. In the context of our four-stage S-curve, we need Design Thinking for the “explore” stage. Design Thinking helps find the right problem to be solved by framing the success criteria of the solution, not just the symptoms of the problem. Understanding these success criteria is as important as the problem-solving phase of development, and the agile mindset is the primary tool to do this work. When products, services, and business models lasted longer, workers focused on deepening their expertise and improving their company's experience curve. As change accelerates, the value of that experience diminishes and may even become a hindrance because that expertise may prevent you from adapting to new methods of creating and delivering value. A 2015 study by Yale researchers Matthew Fisher and Frank Keil, “The Curse of Expertise,”2 found that the more we learn and acquire expertise, the less willing we are to question what we assume we know. Further, in the study discussed in “When Self-Perceptions of Expertise Increase Closed-Minded Cognition: The Earned Dogmatism Effect,”3 the researchers found that the expertise curse can strike nonexperts as well. In their experiments, they found that merely identifying oneself as an expert, regardless of their abilities or knowledge in the area, can create closed-mindedness to new information. In essence, we lose our beginner's mind and create a dangerous blind spot for ourselves. In conversations with business leaders who hold a steadfast commitment to tried-and-true business practices and who have failed to evolve, the reaction is always the same: we did not see the change coming, or, more often, we didn't think it would come that quickly. In some cases, those executives saw a competitor gaining on them. They just could not stop doing what they were doing. They did not know how to change course. In almost every instance, these leaders say they were overconfident in their way of doing things such that they could not pivot even when the end was, upon reflection, obvious. You'll recall from Chapter 4 that Apple took the decision to launch the iPhone at the height of iPod's success. The company anticipated the next wave and took measures to capture it, even at the expense of its then-flagship product. That's incredibly difficult to do, particularly when all instincts are telling you to hold on to current success. We'll talk more about this challenge in Chapter 9 when we introduce you to telecom executive David Walsh. To avoid this trap, leaders need to cultivate mindsets that are predisposed to adaptation. Specifically, they need to become adept at unlearning that which they believe is paramount in order to learn what is new. To understand how to set the conditions for learning that is predisposed to adaptation amidst changing culture, identity threats, and a coming shift in skill demands from technical to social, consider the iceberg (Figure 7.3). We embrace the skills we see and in which we have been trained, while ignoring the underlying fundamentals necessary for a resilient workforce—notably, those skills that enable the adaptation advantage. Those underlying capabilities are what make both learning and unlearning possible. Figure 7.3 The Iceberg: Layers Required for Learning and Adaptation Our Iceberg Model has four basic layers. Explicit skills and knowledge rise above the surface, are visible, and are understood. Enablers, sometimes called soft skills, sit at the water line; they are those things that make us better at our job and relationships but are rarely the abilities for which we are explicitly hired. An agile learning mindset lies below the surface and enables us to continuously learn and adapt. At the base of the iceberg, a resilient and adaptive identity connects our motivation and our purpose. Like an iceberg afloat in the ocean, it's easy to see the explicit skills once learned and often employed. If we are to become adept at learning and adaptation, we will need the whole stack—not just what is easily seen or certified, but the layers deep beneath the surface that support us through the long arc of our careers. As we discussed in Chapter 2, the rapid changes in social and cultural norms cause many people to feel they have lost their status or place. This identity threat at the base of the iceberg makes the entire stack harder to manage. The ability to learn and adapt continuously requires both an agile learning mindset and a resilient and adaptive identity. It is nearly impossible to learn and adapt if your core identity is under threat. Learning, and more specifically unlearning, requires a comfort with vulnerability, an ease with ambiguity, an acceptance of not knowing, and, most importantly, an openness to failure. “Failure is not a bug of learning, it's the feature,” according to Rachel Simmons, a leadership development specialist at Smith College's Wurtele Center for Work and Life.4 In her pivotal book Daring Greatly, renowned sociologist Brené Brown writes, “Vulnerability is the birthplace of love, belonging, joy, courage, empathy, and creativity. It is the source of hope, empathy, accountability, and authenticity. If we want greater clarity in our purpose or deeper and more meaningful spiritual lives, vulnerability is the path.”5 Adaptive workers must tap into this vulnerability and dare to say “I don't know.” These three simple yet difficult words are the first step to developing an adaptive mind. It is the letting go of knowing, it is the foregoing of expertise, it is the bypassing of ego in order to be open to newness, and it is the willingness to shun conventional wisdom to embrace your own internal understanding. Yet to do this, you must first have some security in answering for yourself the fundamental questions: “How do I define myself?” (personal identity), “How do I express myself?” (occupational identity), and “Where do I belong?” (community identity). The deepest level of the iceberg is identity. In order to operate in an accelerating world that demands continual adaptation, we need a mindset outfitted to navigate change. We need an agile learning mindset. The agile learning mindset is separate and distinct from the agile methodologies of software and product development, although it shares similarities with those practices. Susan McIntosh, attempting to define what the agile mindset means in the world of agile methodologies, wrote on infoq.com, “An agile mindset is the set of attitudes supporting an agile working environment. These include respect, collaboration, improvement and learning cycles, pride in ownership, focus on delivering value, and the ability to adapt to change. This mindset is necessary to cultivate high-performing teams, who in turn deliver amazing value for their customers.”6 The agile learning mindset, as we define it (Figure 7.4), contains four components: agency, agility, adaptability, and awareness. Figure 7.4 The Agile Mindset Agency, in social science parlance, is the capacity to act independently and to make choices for oneself. Some describe agency as the opposite of powerlessness. Navigating a rapidly shifting future of work will require the agency to learn and adapt quickly, understanding explicitly that learning is your responsibility. Connect that agency with purpose, curiosity, or motivational drive to fuel your learning and exploration. Agency connects the What, How, and Why that were discussed in Chapter 6 (Figure 7.5). Figure 7.5 Agency Is Rooted in Understanding Your Purpose and Superpowers Agility, and specifically learning agility, is the ability to both learn and unlearn. It is founded in your own learning style to optimize how you take in new information, form new knowledge, and let go of information that is no longer useful. It is flexibility, nimbleness, and responsiveness. Agility includes your ability to pivot not only to take in new information, but also to deliver value when old processes and business models begin to fail, and new ones are required. We very much like how executive recruiting firm Korn Ferry describes learning agility:7

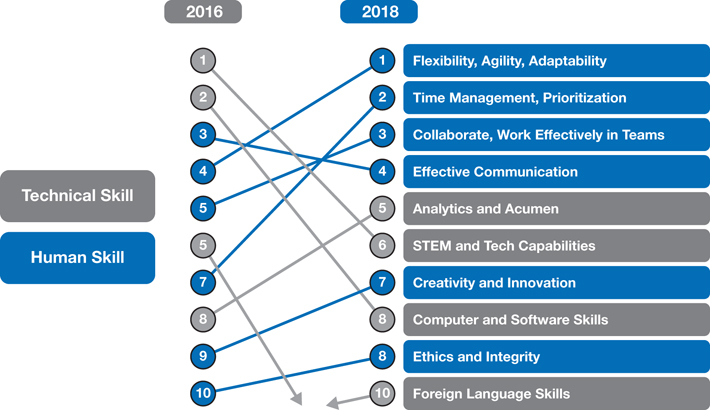

Adaptability is so central to the agile mindset that we made it the centerpiece of this book's title. Charles Darwin is thought to have said, “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, but the most adaptable.” (While Darwin gets the credit for this idea, there's no conclusive evidence to tie him to those words.) In work as in life, then, evolutionary success belongs to those who can most readily adapt. Adaptability enables us to navigate ambiguous situations and work through challenges even when not all the information is clear or even known. In the introduction to this book we shared Professor Jeff LePine's distinction between adaptability and flexibility and it bears repeating here: “Flexibility is the ability to pivot from one tool in your toolbox to another or from one approach to another. Adaptability requires you add something. Adaptability may require you to drop that tool and forge a new one or drop that method, unlearn it and develop an entirely new one.” Awareness starts with an understanding of self. Self-awareness and your sense of personal identity are essential to engage meaningfully in work. Writing in “Collaboration Overload” for Harvard Business Review, researchers Rob Cross, Reb Rebele, and Adam Grant identified an increase of 50% or more in collaborative activities at work over the past two decades. Their conclusion: work is now conclusively a social act.8 Awareness, though, extends beyond the self and your social environment. One must also have a keen market awareness. When the pace of change was slower and, as a result, business models lasted longer, you could successfully hold a job without fully understanding the business model of the organization for which they engaged because your work was, in effect, hardwired into it. That's no longer the case. Change is coming so quickly now that organizations are in a constant dance, pivoting from one business model to the next. In fact, one might argue that the pivot is the business model. As a result, all workers—and most certainly every leader—need to understand how the organization creates value and how they contribute individually and collaboratively to that value creating. And no doubt about it, self-awareness and market awareness are the most important and difficult to master aspects of the agile mindset. Search-engine giant Google set out to discover what made for a high-performing team, hoping they might even be able to create an algorithm to optimize future teams. What they found surprised them. The researchers originally thought that the best teams would be those comprised of the most outstanding individuals. Instead, they learned that “who is on a team matters much less than how team members interact, structure their work, and view their contributions.”9 We discuss this research in greater detail in Chapter 9. To perform well in the collaborative workplace, then, we need the high levels of self-awareness that enable us to productively contribute in teams. We also need great situational or market awareness. You will no longer have a job processing just a piece of work; you will need to know how that work fits into the broader organization, from product through business model. You will need to understand how your organization creates and captures value, and how your activities contribute to that value creation. If you understand this and can continually learn and adapt to contribute meaningfully to that value creation, you will never have to look for a job because you will continually make opportunities happen for yourself. What many people describe—and often discount—as soft skills are the uniquely human skills that are the positive enablers throughout your life and work. These good human skills make life and work far easier. As technological capability advances and encroaches on human cognitive tasks, our uniquely human skills become increasingly valuable. A 2019 research study at Swinburne University's Centre for The New Workforce in Australia titled “Peak Human Potential” found that “the more an industry is disrupted by digital technologies, the more that workers in those industries value uniquely human ‘social competencies.’ From collaboration, empathy, and social skills to entrepreneurial skills, these social competencies are less vulnerable to being displaced by AI and automation.”10 Organizations from the World Economic Forum11 to the Institute for the Future12 enumerate these skills and their value in the future of work. Ultimately, these skills all center on social and emotional intelligence, creativity, communication, judgment, sensemaking, and empathy. And they are all fundamental to the adaptation advantage. We place these skills at the waterline in the Iceberg Model because while they are sometimes evident and explicit on the job, they are also quite often the invisible enablers of your best work. And here's the thing: these so very important skills get better with age, setting up a paradox in a modern culture that tends to value the cognitive skills and rapid learning ability of the so-called “born digital” generation over the experience and uniquely human skills of workers who have developed beyond the sponge-like learning years of the late teens and early twenties. This is a substantial argument for lifelong learning and investment in a multigenerational workforce (Figure 7.6). Figure 7.6 Future of Work Skills Peak with Age and Wisdom Data source: Future of Work Skills from the Future Jobs Report, World Economic Forum. The psychologist Raymond Cattell noted this distinction in his 1971 book Abilities: Their Structure, Growth and Action.13 Cattell separated what he called fluid intelligence (the ability to solve novel problems independent of past experience) and crystallized intelligence (the ability to tap experience to address new challenges). Both, it turns out, are a valuable combination in an adaptive learning organization. Our collective understanding of these cognitive peaks has grown more nuanced with time. Researchers Joshua Hartshorne, a postdoc in MIT's Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, and Laura Germine, a postdoc in psychiatric and neurodevelopmental genetics at Massachusetts General Hospital, address this in their paper “When Does Cognitive Functioning Peak? The Asynchronous Rise and Fall of Different Cognitive Abilities Across the Life Span.”14 Their research points to a broader range of peaks between fluid and crystallized intelligence. “We were mapping when these cognitive abilities were peaking, and we saw there was no single peak for all abilities. The peaks were all over the place,” Hartshorne told MIT News. “This was the smoking gun.”15 “It paints a different picture of the way we change over the lifespan than psychology and neuroscience have traditionally painted,” adds Germine. Vocabulary, comprehension, arithmetic, and reading all peak later in life, supporting the argument that lifelong learning and adaptation is always possible. We asked Dr. Germine for more insight into these emerging discoveries. “The world has changed so much in terms of how we live and how we work that we cannot rely on results from older studies of lifespan cognitive performance to be necessarily true today,” she told us. “Studies from the 1970s on when cognitive abilities peak may not be relevant to today's human cognitive function.” She went on to explain this in a broader context: “Consider the longer view of how humans have adapted over time. We live in regions once uninhabitable to our ancestors. We make use of resources that were useless to our ancestors. We make tools that augment our limitations and extend our longevity and the quality of our lives. Our brains are capable of continual adaptation to new environments, which may explain the many peaks of different cognitive abilities between the old markers of fluid and crystallized intelligence. There is a difference between the time in your life when a particular cognitive ability peaks and brain health.” Brain development, Dr. Germine told us, is a “constant tension between specialization and flexibility.” As we age, our brains tend toward specificity, discarding information that the brain deems irrelevant. To better envision this move toward specialization, Dr. Germine constructed a useful analogy. “A piece of wood can be anything, but once you start the process of whittling it down to make a spear, that piece of wood is not as useful as a material to make a chair. A lot of research about development, aging, and the brain suggests that exposing ourselves to a broad range of meaningful experiences for as long as possible—to continue to try new things and learn new things—might counteract the brain's natural tendency to overspecialize at the expense of flexibility.” That last comment struck us as especially important now. An obsession with hyperspecialization and expertise may actually limit our ability to adapt. Remaining open to new learning, on the other hand, may be the secret to successful intergenerational work forces. We talked with Robert Burnside, former chief learning officer (CLO) at Ketchum, a 96-year-old global public relations firm, about how his firm drew on the longevity advantage while upskilling and reskilling the workforce for digital capabilities. In 2014, Burnside was tapped by the company's CEO to implement a new digital strategy with the firm's 2,000 account services professionals. His approach: team older, often senior employees who lacked digital skills but had deep business experience with younger workers who were digital savvy but hadn't yet learned how public relations can best serve clients. The resulting learning groups included people of all levels, ages, and geographies to maximize diversity, with the explicit goal of bringing everyone's digital and business skills to par. “This was engaging for everyone,” Burnside told us. “In the end, it is a ‘both/and,’ not an ‘either/or.’ We need all the skills, which vary by generation and life phase, and we need to find a way for our people to engage and inform each other.” The example Ketcham set may be useful not just in filling skills gaps; it may also address the growing gap in social and behavioral skills. Both PricewaterhouseCoopers Annual CEO surveys and IBM Institute for Business Ventures Global Surveys are finding that the social or behavioral skills gap is now greater than the technical skills gap. Specifically, the IBM surveys saw a shift in concern about a shortage of technical skills in 2016 to worry about a lack of social skills in 2018. The number-one skill in demand? Adaptability (Figure 7.7). Figure 7.7 Technology Skills Slip as Behavioral Skills Rise (IBM) Sources: 2016 IBM Institute for Business Value Global Skills Survey; 2018 IBM Institute for Business Value Global Country Survey. In the Second Industrial Revolution, we began to embrace skillsets and build careers around them. We created a pathway from apprentice to journeyman to master craftsman based on the acquisition and perfection of certain skills. As we moved from the Second to the Third Industrial Revolution, we identified a growing need for a skilled and trained labor force beyond the trades. It demanded education that extended beyond high school, and stimulated demand for a higher educated workforce. (If you are unfamiliar with the four industrial revolutions, check out the book's introduction where we explain them.) Following World War II, interest in and demand for post-secondary graduates took hold, driving a greater demand for specifically educated college and university graduates. From 1960 to 1990, the number of higher education institutions in the United States doubled, in a period that might best be described as the massification of higher education. Increasingly, hiring companies, and indeed society, became focused on monolithic degrees. Students were told to “pick a good major” to guarantee a path to a good, stable ride up the career escalator. The university trained you in a single skill set, in a single industry, and if you had a decent starting salary, the academy could declare success. Now, while we have unmet needs for a highly educated workforce in fields like data analytics and cybersecurity, we have a huge number of students graduating with debt and degrees they cannot monetize because the skills they were taught were outdated or irrelevant even before they began their studies. To be clear, we neither discredit nor devalue the experience of higher education; we're believers! It's the myopic focus on monolithic degrees for workforce preparation with which we take issue. Higher education has focused almost exclusively on training people in technical skills by offering the false promise that these students could leverage that training for their entire career rather than as a starting point in a long arc of lifelong learning. Exercise: Your Workplace Thinking Style Mark Boncheck, CEO of Shift Thinking, and Elisa Steele, Chairman of the Board of Cornerstone on Demand, developed an elegant yet simple tool to understand your workplace thinking style (Figure 7.8). First, select a focus area from the following: ideas, process, action, or relationships. Once you have narrowed your focus, look at your orientation: Are you a big picture person or a detail person? The simple two-question assessment can tell you where you like to play on a team. Boncheck and Steele describe eight types that result from the four-by-two matrix. (You can read more about this work in their 2015 Harvard Business Review article “What Kind of Thinker Are You?”16) Figure 7.8 Bonchek and Steele: What Kind of Thinker Are You? Source: Mark Bonchek and Elisa Steele. In the cult classic film Glengarry Glen Ross, Alec Baldwin exhorts his salesmen to “always be closing.” In today's world of work, we think organizations should “always be learning” because, as business theorist Peter Senge wrote in The Fifth Discipline and Royal Dutch Shell business executive Arie de Gues echoed in book, The Living Company, “The ability to learn faster than your competitors may be the only sustainable competitive advantage.”

Learn Fast—What Does That Even Mean?

What Do We Mean by Learning? First-, Second-, and Third-Generation Learning Organizations

The S-Curve of Learning: Explore, Experiment, Execute, Expand

The Curse of Expertise: The Challenge of Unlearning

The Iceberg: The Substance Beneath the Surface

Identity: The Core of the Adaptive Mind

The Agile Learning Mindset

Agency

Agility

Adaptability

Awareness

Agile Mindset in Action

The Enablers: Uniquely Human Skills

Why We Need the Agile Mindset: The Broken Education-to-Work Pipeline

ABL: Always Be Learning

Notes