9

Leading in Continuous Change: Modeling Vulnerability, Learning from Failure, and Providing the Psychological Safety that Builds Trusting Teams

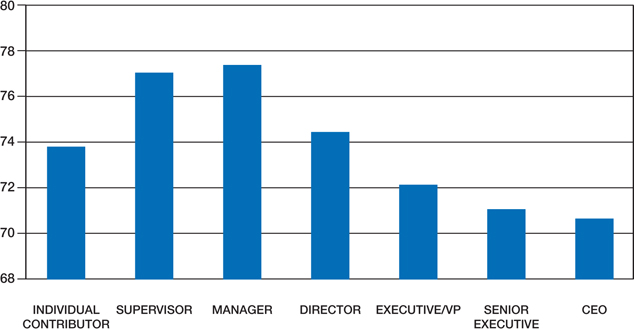

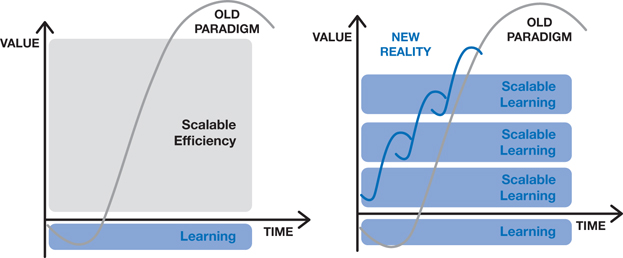

Key Ideas We are driving faster and faster toward a horizon that none of us can see with perfect vision, and we're doing it with one eye on the rear-view mirror. Virtually all of our understanding of leadership was derived from Third Industrial Revolution practices. Many of those leadership theories remain relevant, yet so many other ideas, language, and analogies can be downright dangerous in accelerated change. As we wade into the Fourth Industrial Revolution, we have to be more thoughtful about who we are leading and where we are taking them.We were reminded of that truth when we spoke with leadership guru Jim Kouzes, coauthor with Barry Posner of the seminal book The Leadership Challenge. For nearly 40 years, Kouzes and Posner have studied the best practices of effective leaders, and we wanted to hear his views about what accelerated change means to leadership. “The context of leadership has changed in some very dramatic ways since Barry Posner and I started researching and writing on the topic, but the content of leadership has not changed much at all,” he told us. “The most self-evident and stable truth is that, at its heart, leadership is a relationship between those who aspire to lead and those who choose to follow. It is the quality of the relationship that makes the difference, not the rapidly advancing technology, or the fact that there are more human beings on the planet, or that organizations are more diverse, or that the economy is more global. We've gathered data from over 70 different countries for over four decades, and we continue to find the same results. The more frequently leaders exhibit exemplary behaviors, the more likely it is people will feel engaged, be more productive, deliver higher-quality work, and all the other measurable outcomes you would expect from exemplary leadership.” What, then, are those “exemplary behaviors” that deliver exemplary leadership in the context of accelerated change? How can we drive, eyes forward, to lead the future of work? Oddly enough, we found some answers in cookies and chickens. Emboldened by Milton Friedman's shareholder-value era, corporations embraced the view that leadership should drive productivity to extract maximum value from processes and people. That concept does not apply so well in today's world. As we enter the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the hyperfocus on productivity and value extraction shifts to embrace creativity, innovation, and value created by adapting faster and learning more than your competition. This shift from scalable efficiency that ruled the Second and Third Industrial Revolutions (go back to Chapter 7 if we're losing you here) to scalable learning that is at the heart of the Fourth Industrial Revolution requires a new leadership style, one that inspires human potential (Figure 9.1). Two experiments, one involving cookies and the other using—you guessed it—chickens, best exemplify the old style of leadership that we most need to rethink. Figure 9.1 Leadership Shift from Driving Productivity to Inspiring Human Potential Sources: John Hagel (scalable efficiency and scalable learning) and Heather E. McGowan (leadership for productivity or potential) A look at those two experiments helps us make the point. In his 2015 study of power, Dr. Dacher Kelter, professor of psychology at University of California, Berkeley, and director of the Berkeley Social Interaction Lab, conducted an experiment to illustrate the famous thesis of nineteenth-century historian and politician Sir John Dalberg-Acton: “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Kelter's so-called cookie monster experiment brought together three people, chosen arbitrarily, to work together to complete a routine task. One of the three was randomly selected to be in charge of the team. Midway through the task, researchers put a plate of four warm chocolate chip cookies on the table (Figure 9.2). One cookie remained after each participant took a cookie. Almost always, that last cookie was taken by the person who had been placed in charge. Not only did they take the cookie, but consistently, they ate that extra cookie with gusto, mouth open, dropping crumbs all over themselves. Figure 9.2 Who Gets the Extra Cookie? Source: Photo by Wendy Rueter on Unsplash. Kelter explains, “When you feel powerful, you kind of lose touch with other people. You stop attending carefully to what other people think.”1 Kelter goes on to explain that in most work environments, the very qualities that earned you the position of power—notably empathy, collaboration, and fairness—fade once you begin to feel power and prestige. The cookie monster experiment is one grotesque illustration of what Dr. Travis Bradberry found in his analysis of over 1 million workers. Bradberry is coauthor of Emotional Intelligence 2.0 and president of TalentSmart, a company focused exclusively on emotional intelligence assessments and training. He found that the highest levels of emotional intelligence were found in those in managerial or supervisor roles; the lowest were in those in senior executive and CEO roles (Figure 9.3). Figure 9.3 Emotional Intelligence and Job Title Source: Travis Bradberry, PhD, president, TalentSmart, Inc., coauthor, Emotional Intelligence 2.0. This glide path—from growing emotional intelligence as an individual contributor up through the position of supervisor, then declining to the lowest levels in CEOs—might suggest that you need to ditch the empathy to succeed in business. However, Bradberry paradoxically found that the most successful senior executives and CEOs are those with the highest levels of emotional intelligence; they are able to obtain power and maintain compassion and self-awareness.2 Since nearly any work that is mentally routine or predictable can or soon will be addressed by an algorithm, the work that remains is some combination of labor that is volatile, uncertain, complex, or ambiguous, often referred to by the military term VUCA. VUCA work is all the stuff that technology cannot handle (at least yet) without human engagement. To maximize human engagement and really tap into our adaptation advantage, we need to be more human ourselves, and that means we have to work harder as leaders to develop the empathy, compassion, and even vulnerability that establishes the trust necessary so teams can let go, learn, and adapt to the emerging challenges. In the chase for ever greater productivity, leaders often focus on super performers to carry the day. On its face, this Third Industrial Revolution management style makes sense: identify top performers and direct your energy and resources to their success. Not so fast. A second experiment, this one involving chickens, discovered a flaw in that theory. In the early eighties, Dr. William Muir, an evolutionary biologist and professor of animal sciences at Purdue University, created an experiment in an attempt to increase the egg-laying productivity of hens. Chicken productivity is easy to measure; she that lays the most eggs is the most productive. To test his hypothesis on the inheritability of this productivity to thereby be able to produce a superior breed of egg-layers, Muir created flocks of nine chickens, putting each flock in a cage and selecting the most productive hen from each flock to breed the next generations of ever more productive hens (Figure 9.4). Figure 9.4 In Search of Super Chickens Source: Photo by William Moreland on Unsplash. Interestingly, that's not what happened. Having placed the nine most productive hens into their own flock, Muir noticed something rather awful. The flock quickly dwindled from nine to three chickens. The other six were killed by the survivors, which continued to attack one another incessantly. In reality those prolific hens—or super chickens, as Margaret Heffernan referred to them in her TED Talk “Forget the Pecking Order at Work” (a video very much worth the 15 minutes to view)—only reached that status by subduing the yield of the rest of the flock. It turns out, in hens at least, that bullying behavior is heritable and several generations were sufficient to produce a strain of psychopathic chickens. And what was happening in the other cages? In a parallel experiment, Muir monitored the productivity of the flocks and selected all of the hens from the best-producing cages to breed the next generation of hens. All nine hens survived, fully feathered. Egg productivity increased 160% in only a few generations, “an almost unheard-of response to artificial selection in animal breeding experiments,”3 Muir's research found. Interestingly, Muir repeated this research across varying species over much of the past 30 years and verified the robustness of the method and showed it could be applied to any species. What do super chickens have to do with the future of work, learning, and adaptation? Simply put, when we focus on the “star performers” who come from the “best” schools, giving them the “best” jobs at the “best” companies, we create a sort of Hunger Games, pitting teammates in hypercompetition with one another. It is a practice that is failing us. We are pecking each other to death. Annual reviews, for example, are great for feedback, but they almost always include a ranking—are you a number 1 or a number 5? To be number 1, someone else has to be number 2. No doubt, metric rankings assist management in distributing raises and bonuses, but we need to ensure that ranking doesn't pit our talent against one another. In fact, our obsession with star performers may be our Achilles’ heel. Collaborative research from INSEAD, Columbia University, and VU University Amsterdam found that “talent facilitates performance—but only up to a point, after which the benefits of more talent decrease and eventually become detrimental as intrateam coordination suffers.”4 In the paper “The Too-Much-Talent Effect: Team Interdependence Determines When More Talent Is Too Much or Not Enough,” they looked at three team sports—basketball, baseball, and football—which “revealed that the too-much-talent effect emerged when team members were interdependent (football and basketball) but not independent (baseball).” Football (soccer, for us Americans) and basketball require tight interdependence between players in order to win (Figure 9.5). Figure 9.5 Soccer: An Interdependence Sport Source: Photo by Jannik Skorna on Unsplash. Team play is not essential in just sports. “As business becomes increasingly global and cross-functional, silos are breaking down, connectivity is increasing, and teamwork is seen as a key to organizational success,” write Rob Cross, Reb Rebele, and Adam Grant about their 2016 paper in the Harvard Business Review. “According to data we have collected over the past two decades, the time spent by managers and employees in collaborative activities has ballooned by 50% or more.”5 In short, more of work is interdependent. Or, as Margaret Heffernan noted in her TED Talk, “Companies don't have ideas; only people do. And what motivates people are the bonds and loyalty and trust they develop between each other. What matters is the mortar, not just the bricks.” It's time to think about your super chickens very carefully. Are you pitting your talent against one another or are you creating the conditions, like the cages of the best hens, for optimal human potential? TED Talk Signals Leadership The now-ubiquitous TED Talks are often an early indicator of emerging ideas in culture and business. People say things on the TED stage often long before they become mainstream ideas. It's interesting to note, then, that in 2019, four of the five most-watched talks of all time gave insight into the shifting future of work, and two of those talks tackled the changing nature of leadership. (No. 5 on the list was “Ten Things You Did Not Know about an Orgasm.” We'll leave it to you to decide what, if any, relevance that may have in your future of work.) The five most-watched TED Talks as of 2019 were:

Jim Kouzes and Barry Posner first published The Leadership Challenge in 1987. Now, more than 30 years later, they have produced a suite of leadership books and training programs that focus on five essential leadership practices that have not changed since they began their work together. This, they believe, is the essence of leadership:

We would not do them justice to attempt to summarize their decades of research in leadership, but we will shine a light on two ideas that we think have particular applicability at this unique moment in time. If you take nothing else from Kouzes's and Posner's work, let it be this: model the way and enable others to act in order to lead adaptive teams. By embracing these two ideas, you will set the conditions for rapid learning, unlearning, and build the transformational teams at the heart of your adaptation advantage. While you may assume your team knows who you are, you may be surprised to find they actually do not know what you value. Kouzes told us this story: “In some leadership seminars we conducted at Northrop Grumman Corporation, Ron Sugar, CEO and chairman at the time, came to speak to the executives at his company. His immediate questions to them were, ‘Do the people you lead know who you are, what you care about, and why they ought to be following you?’ These are three wonderful questions, and every leader must be able to answer them. But it's that first question— ‘Do the people you lead know who you are?’—that requires every leader to do some serious soul searching.” Who are you as a leader now? What kind of leader do you want to become? What's the gap between who you are and who you want to be? What do you need to do to become your best self?” We wanted to test this concept, so we spoke with Carol Leaman, president and CEO of Axonify. Axonify is a micro learning platform used in corporate environments to help frontline employees learn in the flow of work. Leaman was previously CEO of PostRank Inc., a social engagement analytics platform she sold to Google, and prior to that she was CEO at several other technology firms, including RSS Solutions and Fakespace Systems. Besides her remarkable track record as an entrepreneur, Leaman has a 97% employee approval rating on Glass Door, a virtually perfect rating. Based on her multiple tours in the CEO suite and her unusually high employee approval rating, we wanted to know how she does it. She told us that while business may be incredibly complex, she models her leadership on simple tenets: I want every single person at Axonify, when they leave us at whatever point they leave us, to look back and think that this was the best place they ever worked. In order to achieve that, I set out every day to create an environment of openness, and complete transparency. I make mistakes. I own them and then I try to fix them.

With the exception of payroll, everyone who works at Axonify knows everything. There is not a single person in this company that has an excuse to say that they don't know who our customers are, or that they don't know what our revenue is, or that they don't know what our targets are, or that they don't know how we're doing against those targets. Every single person sees all the gory details because I fundamentally believe that if people don't know, they make stuff up. People interpret stuff always negatively, not positively.

I host a session called AMA for Ask Me Anything. Employees can anonymously submit questions and no matter the question, I have to answer it on the spot. This is a really important session because it tells me what is on folks’ minds. One of the questions I often get is how I stay so calm. I may be stressed but I know there is always a way. If I model calmness and focus while leading with authenticity and transparency, I find people do their best work and that is my goal: to inspire the best in our employees. When Heather spoke at Axonify's annual summit of their top clients, she was intrigued that the company didn't talk about its technology platform at all. Instead, they spoke about how their clients could create an atmosphere where people do their best work. This is a passion for Leaman, and when she speaks, she shows great vulnerability and authenticity that establishes trust. Trust is the cornerstone of great leadership and essential to the formation of great teams. What if instead of driving productivity you focused on “creating the best place to work” and the atmosphere that inspires optimal human potential and adaptation? Vulnerability in leadership is tremendously challenging. It requires that you leave yourself exposed and, potentially, susceptible to harm. It takes courage and strength to be a vulnerable leader. When Leaman admitted her errors and opened herself to be asked anything, she demonstrated strength in vulnerability. Too often, we think of vulnerability as a weakness, but University of Houston research professor and best-selling author Dr. Brené Brown has convinced millions over nearly 10 years that vulnerability can also be the basis of strength and connection. We say it often enough to be a mantra: as machines do more and more routine and predictable work, humans need to be, well—more human. More of our work is knowledge based, rooted in ideas, ideas come from humans, not technology tools. In Chapter 8, we highlighted recent global surveys of corporations that found an increase in unmet demand for individuals with uniquely human skills, skills from empathy to compassion to judgment to creativity. This is not just true for workers, but it is now especially true for leaders. At the base of all these skills is vulnerability. And vulnerability is anything but weakness. In her work with the military, Brown noted that there is no courage without vulnerability. “Vulnerability is the birthplace of innovation, creativity and change,” she writes.6 If that is true, where is leadership on this? One of Brown's latest books is called Dare to Lead. In it, she examines how and why vulnerability is essential to modern leadership. Vulnerability establishes trust and the safety to share what you know (ideas) as well as what you do not know (gaps). When we do not hear all the ideas that come from our team, we experience the loss of human potential. When we do not hear when our teams need help (gaps), that is a loss of opportunity. It is an unfilled capability gap. According to Brown, a leader is “anyone who takes the responsibility to find the potential in people and processes and has the courage to develop that potential.” That leadership can come from surprising places. In recent years, a number of young people have stepped up to take that responsibility with courage. Greta Thunberg, who was nominated for a Nobel Prize at the age of 16 and honored as Time Magazine's 2019 Person of the Year, led rallies across the globe and spoke passionately to world leaders at the United Nations, demanding they take action on climate change in 2019. Malala Yousafzai has become an outspoken advocate for girls’ education in the Middle East and the youngest recipient ever of the Nobel Peace Prize. The survivors of the Parkland School shooting are speaking out on gun safety and leading the fight for legislative reform. All of these leaders assumed the responsibility and showed the courage to voice their concerns for their peers and their generation, often when their lives were literally at stake. Agree with them or do not, but you cannot deny that they are stepping up and showing incredible vulnerability and courage. What they display is what Dov Seidman, CEO of global consultancy LRN Corporation, refers to as moral leadership. Moral leadership, he says, is “focusing on human progress and improving the world, having the courage to speak out for principles and being willing to ask tough questions about right and wrong.”7 Moral leadership, Seidman's research suggests, is both in short supply in business and could offer a path to performance improvement. From LRN's survey of 500 business executives: Sixty-two percent of employees believe their colleagues’ performances would improve if their managers relied more on their moral authority than on their formal power and 59% say their organizations would be more successful in taking on their biggest challenges if their leadership had more moral authority.8 We see moral leadership in business every day. In 2018, Nike decided to celebrate the 30-year anniversary of their “Just Do It” campaign with an ad featuring controversial former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick. Kaepernick was, and remains, at the center of controversy when he decided to “take a knee” during the playing of the National Anthem to protest the deaths of African Americans at the hands of police. While the response to the ad from social media was mixed, Nike stock reached an all-time high the week they released the ad, a bump of $6 billion in market capitalization. Hobby Lobby, a chain of arts and crafts stores, believed a mandate in the Affordable Care Act that required employers’ insurance to cover contraception, including access to the morning-after pill, violated the founders’ religious beliefs. The company took its case all the way to the Supreme Court, which found in 2014's Burwell v. Hobby Lobby that the mandate did, in fact, violate a privately held company's right to religious freedom. Publicly expressing its values hasn't been bad for Hobby Lobby's business. The private company continues to successfully operate more than 800 stores across the United States. We wondered how the concept of vulnerability played with Leadership Challenge's Kouzes. He told us this story: One of my friends owns a coffee farm, and when he was first starting out his agronomist offered him some advice. He said that they needed to build a buena casa—a good house—in order to provide the right kind of environment in which the coffee plants could thrive. They could dig a shallow hole, put a coffee plant in it, and it would produce for a short while, but it wouldn't have the flavor and the longevity that it would have if they dug a deep hole filled with nutrient-rich soil. We have been digging shallow holes around all of these human issues, and we haven't yet built a nutrient-rich environment in which it is possible to have conversations about vulnerability, compassion, empathy, and emotional intelligence. While we've begun to build a buena casa in some organizations in which these kinds of relationships are more likely to thrive, we have a long way to go. More so than before the need is there for us to develop and sustain a richer and deeper human connection.” Throughout this book, we have aimed to model vulnerability by sharing our own failures and challenges. Vulnerability does not mean oversharing personal details, but rather revealing information that demonstrates what you, as a leader, believe and why you believe it so that your team can connect with you authentically, feel safe to share with you, and engage with you in pursuit of company missions based upon shared values. Vulnerability and trust are not new ideas, but they take on new meaning when accelerated change enters the scene. In order to learn and adapt to new technologies, new roles, and new business models, we have to think like a trapeze artist and let go of one bar so we can grab the next. If you are asking your team members to leap, you have to assure them there is a net to catch them should they fall (Figure 9.6). This process of letting go of who you are (role) and how you did things (technology and business model) requires both vulnerability and courage in an environment of trust. Figure 9.6 Leaders Make the First Leap of Faith Source: Photo by Sammie Vasquez on Unsplash. When we asked Kouzes about this concept, he had another story for us: I was talking to a friend of mine who's a race car driver by avocation. He will tell you that when you are driving fast, you have to pay more attention, and you can't let your mind drift. You can't look elsewhere. You just have to stay focused on the road ahead, otherwise it can be very dangerous to yourself and others. The same is true in a fast-paced environment. If you're a leader in a fast-paced environment, you just have to pay more attention, and you have to be more present. I'm not sure that that's changed the content of leadership; it just means we have to do it more frequently than we may have been doing it before when things were slower. We didn't have to be as attentive, perhaps, as we do today. Further, when you're on a racetrack by yourself, it's just you, the track, the walls on the sides, and the infield. You don't have to worry about other drivers. But when there are a lot of other race cars going fast on the track with you, it certainly increases the skill you need as a driver. Analogously, now that we have all these other forces moving fast, it's increasing the need for us to be more skillful and competent than before. That's the intensity part. We are in that intensity now. You are a race car driver and your focus and situational awareness are essential (Figure 9.7). Figure 9.7 Racing Takes Great Situational Awareness Source: Photo by Max Böttinger on Unsplash. In their book Human + Machine, Paul Daugherty, chief technology and innovation officer, and Jim Wilson, managing director of research, both at Accenture, suggest that we start thinking, and leading, like the navigation application Waze. Long ago, we navigated through physical space by using the stars as our guide, and then cartographers developed maps, which were eventually printed. In time, these maps were digitized and linked to powerful global positioning satellites (GPS) to pinpoint our place on them. Now, we are hyperconnected and interdependent and we navigate through real-time flows of data. When we drive using the Waze application, we are contributing to the flow of data that is directing our car and others to avoid traffic, accidents, and police speed traps. It is a symbiotic relationship. We need to start thinking this way as we navigate leadership by sensing and responding in order to tap into our adaptation advantage. In 1979, Fritz Machlup coined the terms “stocks of knowledge” and “flows of knowledge” to delineate the difference between how knowledge is recorded and how it is transmitted.9 Back in 1979, knowledge was transferred primarily in three ways: person to record, record to person, and person to person. Although those methods have remained, the Internet has added a fourth dimension to all those transmissions; now knowledge can flow from record to record without human involvement, as evidenced by the Internet of Things—sensors that collect, share, and act on input without human intervention. In this world of increasing data, flows of knowledge, and accelerated change, a leader must be a constant learner. In their Harvard Business Review article “The Best Leaders Are Constant Learners,”10 Kenneth Mikkelsen, coauthor of The Neo-Generalists, and consultant Harold Jarche suggest leaders follow a simple Three Ss formula: seek, sense, and share. Seek is about filtering the most important emerging data for what is important through trusted networks that can help check your blind spots and bridge your gaps. Sense is how we make meaning of the uncovered information to ourselves and our organizations. Share is how we transfer that knowledge back through our networks and with our teams and colleagues to elevate everyone's situational awareness. Sharing also builds respect and trust across our networks and with our teams. To build a team that continuously learns and adapts, that learning has to start with you. Your own learning must be evident in your ability to say, “I don't know” and in your willingness to admit errors and explain failures so you learn from and through them. In the past, leadership often meant the person at the top of the organizational chart was the unquestionable expert. No longer. While we encourage you to be a curious learner, we also want you to realize that you do not need to know everything. We are moving from a complicated world to a complex world (Figure 9.8). A complicated world has many intersecting parts, yet it is largely deterministic. A complex world, on the other hand, has plenty of moving parts whose properties and behaviors emerge and change as situations vary. In a complicated world, you can predict outcomes. In a complex one, you need to constantly adapt in order to direct outcomes. Figure 9.8 Complicated to Complex In a complicated organization, the leader likely has sat in most of the chairs she came to manage. Even if she skipped a couple of roles, she probably has most, if not all, of the skills and knowledge to do the work of those she manages. In complex environments, new flows of knowledge, skills, and activities continually reshape the organization in ways leaders may not even be able to predict, let alone be trained for. That lack of knowing leaves many leaders uneasy. We often hear from leaders that they have people reporting to them who have skills and knowledge that they themselves lack. Some leaders even become concerned that their team members, with their specific skills, could take over the leadership role. But even if you can't do the work of someone on your team, you can do yours. Leadership is not about you having more talent than each of your direct reports; rather, it's about your ability to integrate and orchestrate their talent toward your goals. This leadership style is the essence of the adaptation advantage because it enables talent to learn, expand, and reorganize in preparation for as yet unseen opportunity. By now, we hope we've made the case that vulnerability is essential to establish the trust necessary to set the stage for your teams to engage. If you are a leader and you are concealing your shortcomings, you are actually creating a weakness—the bad kind—for your team. Let us say that again: hiding your weaknesses or pretending you know the answers is not positioning you to be a better leader. Instead, you are encouraging your people to hide their knowledge and skills gaps, creating a team that is weak and compromised. Having the courage to show your weakness, embracing not knowing, and admitting mistakes is how you model vulnerability so that your people will be open with their own gaps and raise their hands when they need help. When you model vulnerability and encourage your team to do the same, you establish a safe place for your team to create, collaborate, learn, and adapt. And that is essential to the foundation of effective teams. In 2012, Google set out to use their data expertise to understand what made some teams successful while others failed. They code-named the project “Aristotle” because of the philosopher's famous line “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts” and to signal their theory that we can do more together than any one of us can do alone. They studied 180 teams from around the globe for over two years to find the answer to the question “What makes an effective team?” They looked at everything from IQ to gender and racial compositions to social connections. What they found was striking. It mattered far less who was on the team than how the team worked together. The number-one determinant for the most successful teams was psychological safety or “the individual's perception of the consequences of taking interpersonal risk.”11 Or, as Dr. Brown would say, the safety to be vulnerable. Even at Google, an organization filled with intellectual stars, it wasn't IQ that mattered; it was how those stars worked together. Google determined that in addition to psychological safety, it was essential that teams had dependability and accountability, structure and clarity, meaning, and purpose. Teams must hear from all members, respect all perspectives, and know that all players must feel comfortable to disclose failures and gaps of knowledge as well as skill in order to pursue the team's mission with a clearly defined mandate. The term psychological safety, made popular by Google, was originally coined in 1999 by Amy Edmondson, PhD, from Harvard Business School, in her groundbreaking paper “Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams.” Dr. Edmondson discovered the concept of psychological safety in the 1990s when doing research into team performance in healthcare—specifically looking at how and why medical errors occur. Edmondson sought to understand why some teams performed better than others. Was it because they made fewer mistakes? She was surprised to find out that they did not, in fact, make fewer mistakes. Rather, they had a team dynamic that made it more comfortable to admit, discuss, and learn from errors. She synthesized her 20 years of research in her book The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. In the book, Edmondson suggests that since so many of our economies are now based upon knowledge work, “for knowledge work to flourish, the workplace must be one in which people feel safe to share their knowledge!”12 In our research for this book, we spoke with Duena Blomstrom. While her background is in finance and technology, Blomstrom recently founded a new company called Peoplenottech that has built a machine learning–powered software solution using a proprietary algorithm to redefine employee engagement, team formation, and health, all with a focus on psychological safety. As her company name implies, Blomstrom, despite her deep knowledge of and experience with technology, believes that it is not the technology tool that counts most, but rather the people and how they use those tools. Blomstrom told us she defines a psychologically safe team as “one that feels like family and moves mountains together. Think back to the last time you made some magic with the team, how you were open and debated and vulnerable and learning, creating, and getting stuff done. That well-oiled machine that felt fun to be a part of. That was psychologically safe.” In order to achieve this optimal team, Blomstrom thinks we need “employees to trust they have permission to be authentic without fear of any repercussion and bring their entire selves to work, they need to see leaders who admit when they fail, don't sugarcoat it in acronyms, say so often, and ask prying, emotionally involved questions that show they truly care about their employees. Needless to say, for them to show this they need to start with managing it within their own leadership groups first and transform those which are now nothing but impression management showcase stages today into psychologically safe management teams.” Impression management, a term coined by Erving Goffman, is “a conscious or subconscious process in which people attempt to influence the perceptions of other people about a person, object, or event by regulating and controlling information in social interaction.” Harvard's Edmondson centers her definition of impression management on the four things leaders typically try to avoid: appearing incompetent, seeming ignorant, looking unprofessional, or acting intrusive. In order for transformational learning to occur in a learning and adaptive environment, we believe individual workers must be comfortable with not knowing, with ambiguity, and with potentially being wrong—all things not possible without psychological safety. Unless you were a trapeze artist, you would not feel safe on a trapeze letting go of one bar and reaching for the next if the net was removed. Psychological safety is the net necessary for optimal team performance, engagement, and adaptability. In their most recent State of the American Workplace report, Gallup found that only 3 in 10 employees felt their opinions were valued at work. Gallup predicts that by “moving that ratio to 6 in 10 employees, organizations could realize a 27% reduction in turnover, a 40% reduction in safety incidents, and a 12% increase in productivity.”13 Moving that needle, though, is a real challenge. You may avoid tough conversations to spare people's feelings. Maybe you are avoiding your own discomfort. Avoiding tough conversations, though, robs your team of the feedback that may help them grow or adapt. Dr. Brené Brown puts it succinctly: “Clear is kind. Unclear is unkind.” Harvard's Edmondson built her book The Fearless Organization on the notion that we can care about our team members personally and still give brutally honest feedback to help them change directionally to evolve and adapt to maximize their human potential. This concept of radical candor unfolds in a three-step process: (1) setting the stage, (2) inviting participation, and (3) responding productively. Setting the stage is about framing the reality of your challenge for maximum engagement. Inviting participation is really all about the leader and how you make it safe and okay to admit, explore, and learn from mistakes. Responding productively is holding trust by not penalizing the engagement you worked so hard to elicit and instead expressing appreciation for participation, destigmatizing failure, and creating an environment for continuous learning. This ultimately is a process that is deeply respectful and uplifting. Remember the 70–20–10 rule: 10% of our learning comes from structured instruction, 20% comes from working with others, and 70% comes in the flow of work. When you consider this in total, what the rule is really reflecting is that 90% of learning at work happens in collaboration. It benefits us as leaders, then, to set the conditions to maximize our teams’ learning from both success and failures. As our world has become increasingly complex, tenure in jobs has become shorter, and continuous learning has become a nonoptional requirement for staying relevant, it's no surprise that stress levels have skyrocketed. According to the World Health Organization, 300 million people report being depressed.14 Add anxiety to this mix and that number goes up significantly, though it is difficult to know for sure just how high; fewer than half of those folks suffering from depression seek treatment. The global professional service firm Aon's “Global 2020 Medical Trends Rate” report cites stress as being in the top five global concerns for healthcare costs and risk.15 To better understand the impact of stress and mental health on performance, we spoke with recently retired Major General James Johnson, former executive director of human resilience for the US Air Force. Johnson was responsible, he told us, for “optimizing human performance using strategies focused on wellbeing and resilience.” What he learned in that role is valuable to leaders in every type of organization. Johnson shared that insight in an email to us: Essentially, we found that the success of our strategies ultimately hinged on leaders consistently using approaches that leveraged research. In this vein, we knew we had to focus first on equipping leaders, because if leaders, from the most senior officer down to the front-line supervisor, don't understand the strategy and underlying science, they won't buy-in, and they won't adequately communicate the strategy to subordinate levels, and, at the end of the day, organizations won't buy-in, and you won't achieve your desired outcomes. In fact, without relying on research-based strategies, not only do we jeopardize positive progress, we run the risk of implementing programs that could actually do more harm. A good example of this is the DARE (Drug and Alcohol Resistance Education) program, which ignored scientific evidence, and continues to inspire more kids to turn to drugs rather than “just say no.”

This focus on leaders and research-based strategies is so important to our work, especially when you consider we share some of society's most distressing human problems that are resistant to simplistic ad-hoc solutions; everything from depressive illness to sexual assault, family violence, and suicide. A study that highlights the challenges (Heyman, Slep, & Nelson, 2011), found that one in three of our people anonymously reported problems with these kinds of issues, including substance abuse, suicidal ideation, and family violence. We also found that two out of three of them indicated these were secretive problems. That's a significant and surprising issue, in our case negatively impacting over 100,000 people.

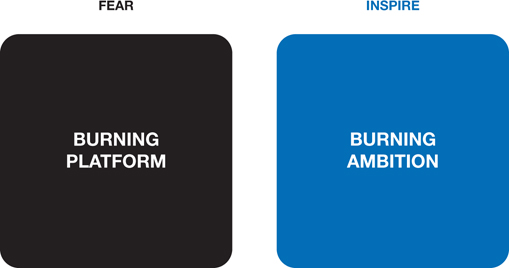

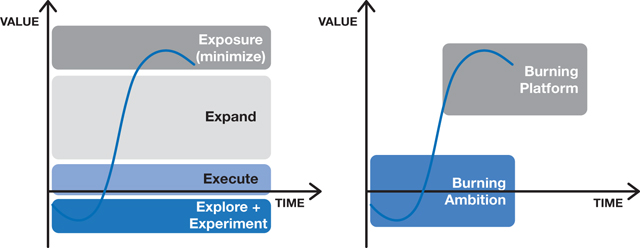

Ultimately, we'll see real success with our human wellbeing and resilience strategies, even those dealing with issues as difficult as suicide prevention, when we equip leaders with research-based strategies and implement programs strengthening social support, promoting development of life skills, and changing policies and norms to eliminate mental health stigma, while encouraging effective help-seeking behaviors. If the military sees mental health as an essential driver of performance, we believe it is high time that corporations make mental health and stress reduction not just a human resource benefit but a core business strategy. Globally, 1 in 7 individuals suffers from either a mental health or substance abuse disorder. In aggregate, that's over one billion people. The most common mental health challenge is anxiety, affecting about 4% of the global population.16 Simple math: if you have more than seven direct reports, there is a good chance that at least one of them is suffering. How aware are you of the mental health of your team? Adaptation is harder, if not impossible, when in a mental health crisis. The term digital transformation is used ad nauseum in popular and business literature. Most of us think of it as a one-time thing when you shift to a paperless office or when you do everything through a software application. In truth, digital transformation is a multiyear, multiphase process of transforming to a learning-centric environment that leverages data for insights and learning. Web strategist Jeremiah Owyang identifies seven components of digital transformation: strategy, data, customer experience, organizational alignment, analytics and AI, people and culture, and innovation.17 We'll talk more about this in Chapter 10. Considering that most companies, except those born digital, are in various places across these dimensions, we turned to Jim Kouzes again to talk about how leadership can make the difference in such profound business and organizational change. “Exemplary leadership makes a significant difference in organizational performance,” he told us. “For example, in a survey of 94 large companies, researcher Richard Roi asked executives to rate their company's senior leadership on transformation leadership using The Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership® as the framework. What he discovered in his analysis of the data was that there was a dramatic relationship between transformational leadership practices and company performance. Companies with a strong and consistent application of The Five Practices had net income growth of a positive 841% versus a negative 49% for companies with a low incidence of leadership practices. Similarly, stock price growth was 204 percent for strong transformational leadership practices companies compared with only 76% for companies with a weak implementation of practices. The harder business measures, as well as measures of employee engagement, all indicate that organizations over the long term will produce better results when they exhibit transformational leadership than when they are merely transactional.” We spoke at length with David Walsh, an entrepreneur, investor, and business operator who served as CEO at Genband (which merged with Sonus Networks in 2017 to form the publicly traded Ribbon Communications) and has gone on to found cloud communications platform company Kandy.io. Walsh witnessed firsthand many evolutions and adaptations in telecommunications over his 35-year career in that sector. Speaking specifically about the leadership required for transformational change and continuous adaptation, he says, “Change in organizations is very hard. People cling to the skill they learned and the culture they built around it. This is particularly true in technology companies. People hold onto the original technology that made them successful often long past its usefulness. They ignore the change happening around them until it's too late to pivot, as others have already made the shift and the opportunity is gone.” Timing, it turns out, makes all the difference when navigating change. Walsh makes this particularly insightful observation: Often companies at their peak of profitability are at their greatest risk of failure, which makes it even harder to accept that change is needed. I've found that being a benevolent dictator helps drive change in the early stage of the pivot. Bringing in talent from outside the organization with different skills and experiences is key. To reduce resistance, it's also important to repurpose talent from within so people believe they can be part of the future. In order to pivot, the mission has to be clear, the goals have to be well defined, and everyone has to be bought in, from the Board all the way through the entire organization. Then you align your troops along a narrow front and attack with overwhelming force, landing and expanding until you succeed. The people you pick for the mission not only have to be able, they need to believe in the mission. Placing the talent into a separate division or establishing a new brand helps send the message that something new is happening and helps united the team around its mission. I've done this a few times, pivoting from voice trading to electronic trading, from making hardware and software to a business of connecting them together and from using the software of a company to building a SaaS business out of it. All of these pivots required a different culture and business model and the ability not only to fight externally for customers but to fight the “enemies from within” who resisted change at every pass. In 1947, German American psychologist Kurt Lewin introduced a simple three-stage model for change management: unfreeze (today we might say unlearning), change, freeze. Lewin's model was a breakthrough in change management because it acknowledged the letting go of old mindsets and behaviors in the unfreeze phase and the crystallization and standardization of processes in the freeze phase. The challenge of this model today is that change is a not a one-time thing; freezing, then, is probably never a good idea. Fast forward a few decades from Lewin's three-phase model to the time when change management gurus adopted the Satir Change Model. Created by family therapist Virginia Satir in the 1970s, the model assumed change was a one-time thing, a single process from one state to another with five phases: (1) late-stage status quo, (2) resistance, (3) chaos, (4) integration, and (5) new status quo. Satir's model acknowledges both resistance and chaos but still keeps an implied promise that you will only need to be uncomfortable and vulnerable once as you go through a single transformation. To refer to digital transformation in this transactional way is wrong. Transformation is continuous and moving from phase to phase is a series of learning processes. In order to learn and adapt, you need to unlearn and let go. To deal effectively with this continuous change, you need to get comfortable with being uncomfortable—comfortable being wrong, comfortable not knowing, and comfortable learning from failures. This requires stretching as well as changing your perspective as often as possible (Figure 9.9). Figure 9.9 Become Comfortable with Being Uncomfortable Source: Photo by André Noboa on Unsplash. Years ago, Heather had a colleague who explained the difference between mistakes and failure. He said, “Mistakes should be avoided, and failures embraced. Mistakes are things that go wrong and we do not know why. Failure implies a theory from which we can learn from the results. Embrace failure, avoid mistakes.” In the scalable efficiency and shareholder-value era, many business leaders used the phrase “create a burning platform” (Figure 9.10) to signal an environment that forces human behavior changes. That phrase originated from a story of an oil rig explosion in the North Atlantic sea off the coast of Scotland in the 1980s. One hundred and sixty-six crew members and two rescuers lost their lives when the rig caught fire. Andy Mochan, a superintendent on the rig, and one of the 63 survivors, was asked how he managed to live when so many perished. Mochan noted that the oil had surfaced and ignited, debris littered the water, and he knew that because of the water's temperature, he would likely survive for only a few minutes if not quickly rescued. Despite the bleak information and training to the contrary, Mochan jumped 15 stories from the platform to the water. When asked why he leaped, he did not hesitate. “It was either jump or fry,” he said. His was a choice between probable death or certain death. Mochan jumped because he felt the price of staying on the platform was too high.18 Figure 9.10 Beware the Burning Platform Source: Photo by Stephen Radford on Unsplash. Fear is a powerful driving force. We have used the concept of creating life-threatening fear to motivate human behavior change. Fear can work in the short term, but fear as a motivator does not endure. We spoke with Peter Sheahan, founder and CEO of the Karrikins Group, a global behavior change firm. Sheahan suggests we drop the term “burning platform” and instead “create constructive tension by choosing to create a burning ambition over a burning platform” (Figure 9.11). Figure 9.11 From Burning Platform to Burning Ambition Source: Peter Sheahan, CEO, Karrikins Group. If you consider the phases of value creation we discussed in Chapter 7, we move from exploration of the problem space to experimentation with ideas to execution of a product or service to expansion of that value through scaling to finally (limiting) your exposure and risk in decline. If you consider these phases, the burning platform metaphor is most applicable to the late stages of potential expansion. More likely, though, the burning platform concept feels most real when you seek to limit your exposure and risk (Figure 9.12). Figure 9.12 Phase of Value Creation and Protection and Burning Platform versus Burning Ambition As David Walsh pointed out from his experiences in telecommunications, these phases are far too late to successfully pivot. The greatest challenge may be leading the behavior change from protection in expansion and (minimizing) exposure to exploration and experimentation. For example, Apple successfully did this by introducing the iPhone when the iPod was still ascending rapidly. If you focus on creating the conditions for burning ambition, leaning into scalable learning rather than relying on scalable efficiency, you will be better positioned for the pivots and continuous adaptation in accelerated change (Figure 9.13). The reskilling and upskilling we've discussed throughout this book are not only for those displaced by change. Rather, they are an essential part of all work. We need both our teams and our leaders to be continuously expanding (reskilling) and deepening (upskilling) their capabilities and knowledge as an integral part of work. Work is learning and work should be organized as a successive series of learning tours designed to expand our individual and collective capacity (Figure 9.14). Figure 9.13 Old Paradigm versus New Reality and Scalable Efficiency versus Scalable Learning Figure 9.14 Learning Tours to Increase Capacity This is a long chapter so we will keep the summary short. Drop the cookie. Forget the super chickens. Be vulnerable and tell your people what you care about so they can align with your values. Establish safety, trust, and accountability. Check your blind spots and mind your gap by committing to your own learning plan. Own it and apologize when you fail and get up every day with the goal of making your company the one that your team will look back on and say, “That was the best place I ever worked.” Do that, and you'll have a strong foundation for your adaptation advantage.

You Are at the Wheel

Leadership, Power, Cookies, and Chickens

Emotional Intelligence and the Cookie Monster

The Super Chicken Paradox

What Makes a Modern Leader?

Model the Way: Introduce Yourself and Share Your Values

Model the Way: Be Vulnerable

Model the Way: Trust Is Essential at Speed

Model the Way: The Best Leaders Are Curious Learners

Enable Others to Act: You Do Not Need to Know Everything

Enable Others to Act: Establish Psychological Safety

Enable Others to Act: Encourage Respectful Discourse and Dissent

Enable Others to Act: Prioritize Wellness

Transformational Leadership

Transformational Leadership and Change Management Models

Leading with Fear: The Burning Platform

Putting It All Together

Notes