11

Capability Is King: Looking Beyond the Resume to Design Your Adaptive Team

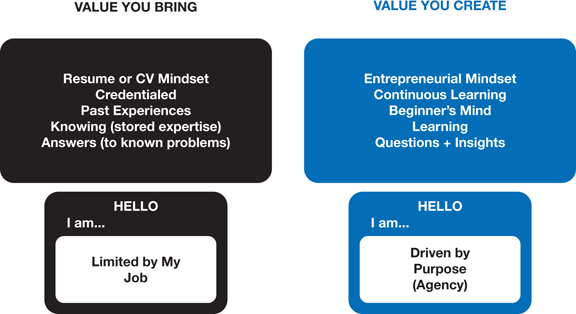

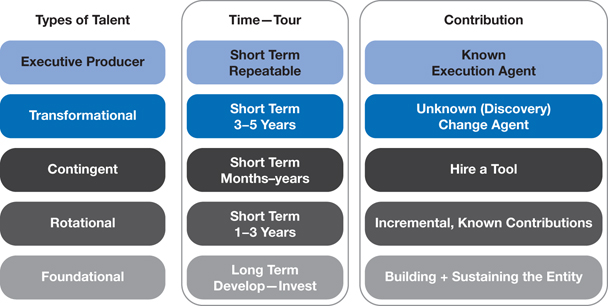

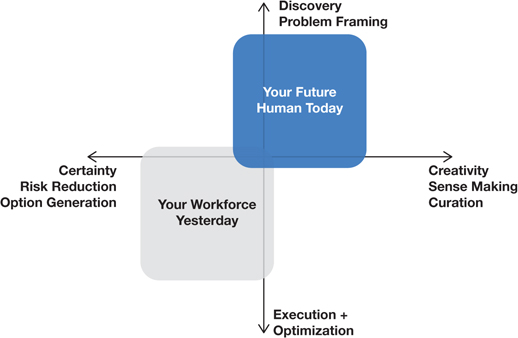

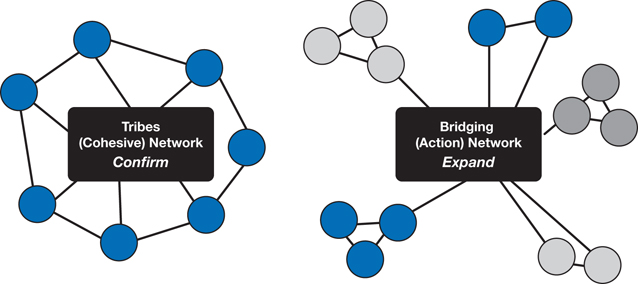

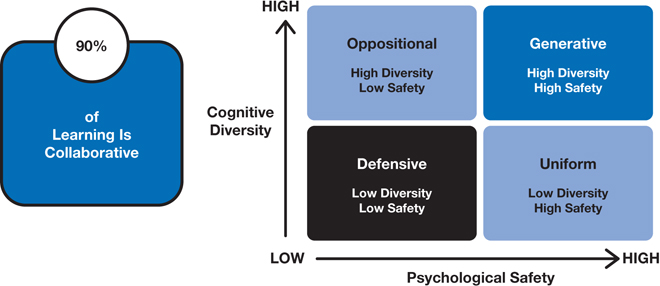

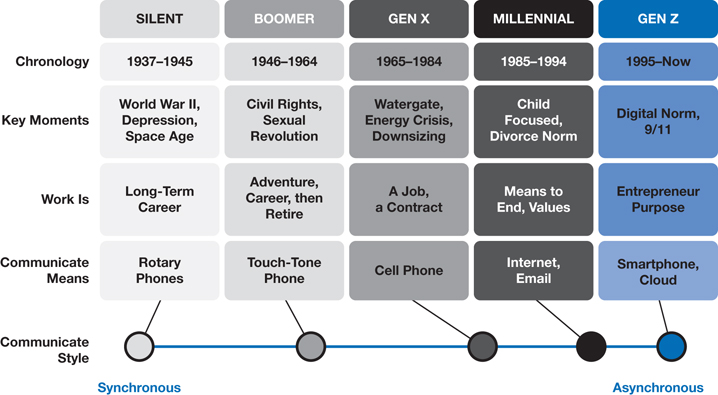

Key Ideas Imagine: it's Christmas Eve and you still have presents to wrap. A small piece of jewelry. A child's bicycle. A sweater. A drum set. Theater tickets. Some power tools. You want to surprise your family with these gifts in the morning and all you have is a roll of wrapping paper, some tape, and a pile of 8 × 10 boxes. How are you going to wrap these different-sized gifts with these uniform supplies? Every day across the globe, business leaders attempt this same packaging trick when they look at their workers as boxes on an organizational chart wrapped neatly in a job description. This inside-the-box thinking worked well enough when processes and responsibilities were constant, skills and credentials were fixed, and boundaries between roles were well defined. Executives could manage people in roles, conducting business like a concert master running a well-rehearsed score. The business changed slowly enough that the boxes and people in them could quietly evolve until, at last, a company-wide re-org came along to shake things up. But today there is a consequential problem with these static organizational structures. They tend toward homogeneity of thought that misses even the most obvious signals that business is changing. Strict roles can lead to a “stay in your lane” mindset that discourages workers from speaking up when they see challenges and opportunities that fall outside their clear job definition. If you've ever heard someone in your organization say, “It's not my job,” you have experienced this kind of trapped thinking that assumes that someone else, in some other role, has a better view and clearer responsibility. That is never a safe assumption, particularly in the fast-moving future of work. Almost paradoxically, these staid structures can also lead to groupthink. Workers hired for the same style, skill, experience, and credentials—what some might mistakenly call a “culture fit”—create uniform teams that think uniformly. It's not that workers are afraid to rock the boat; rather, with everyone rowing in exactly the prescribed direction and tempo, the boat doesn't rock at all. That may feel good and steady in the moment, but it doesn't set organizations up for success. Still, this dangerous approach to hiring and organizing workers has been the anchor of employee management for decades, if not centuries. And to be clear: the job description and the organizational chart have never been a good proxy for real human talent. We need to rethink the organizational chart. New knowledge is entering your organization at all levels. That information needs to flow throughout the organizational chart, rather than up and down hierarchical maps. That alone demands that you think differently about your decision-making process and, more importantly, how you form your teams. We are moving from a time when we hired and organized teams based on past experience at solving known problems to a new era that will harvest value from a beginner's mindset and entrepreneurial outlook well suited for identifying new opportunities and innovative approaches to addressing them. In short, the ability to find new insights will be more valuable than answering known problems (Figure 11.1). Figure 11.1 From the Value You Bring to the Value You Create Job descriptions have been around for centuries, evolving from hand-painted “Help Wanted” signs in shop windows in the 1600s to employment ads in newspaper classified sections that emerged in the 1800s and on to detailed and searchable listings of Internet-based job boards in the 1990s. Today, digital technology and algorithmic tools claim to be able to remove bias of race, gender, and culture in job descriptions on sites such as textio.com. As we continue into the future, modern technology will absorb many explicit tasks that achieve known results. In other words, anything mentally routine or predictable may be done by an algorithm, leaving the less predictable, creative, and insightful work to humans. The funny thing about “less predictable work” is that it's difficult to codify in a straightforward, easily posted job description. So, let's be very blunt: in the fast-changing future of work—where workforce management is a process of continually aligning talent to current and changing needs—the structured organizational chart and the written-in-stone job description are virtually useless. In fact, they may be dangerous because they discourage workers from learning and adapting and instead encourage them to rely on their potentially outdated skills and knowledge. As the speed of change continues to accelerate, so will future work requirements. We can hire for next-generation skills as they emerge, but by the time we identify a need, approve a new hire, specify and describe those skills in a job description, seek out and hire qualified candidates, and onboard and acclimate new employees, the need for those skills is replaced by the next wave of skills coming up after them (Figure 11.2). Figure 11.2 Accelerated Change Can Eclipse Long Hiring Timelines More challenging, a focus on specific skills risks missing out on tacit knowledge that often makes those explicit capabilities come to life in an organization. Explicit skills are the “what” and “how” of productivity; tacit knowledge is where the “why” meets the “how” that help workers know when to put those explicit skills to work. Assuming an organization wants to attract and retain the best talent, the question becomes how to identify workers who bridge these essential capabilities. Job descriptions, almost by definition, describe capabilities and attributes without the context of a dynamic organization, and almost always these descriptions are of roles in isolation from each other. Most importantly, “jobs” as we have known them—tasks to do—will become less and less relevant as workers “do” less and create, collaborate, adapt, and learn more. As the Harvard Business Review study discussed in Chapter 8 found, collaborative activities at work have increased by more than 50% over the past two decades. Beyond “work well with others,” we need to find a better way to address this shift and move beyond old-fashioned job descriptions. For insight into how to start doing this, consider what Joanna Daly, vice president of human resources at IBM, told us: “The half-life of skills is getting shorter. Hiring someone because they know something that's in demand today is going to be of limited value. In the past, it might have been a good recruitment strategy, because maybe that skill or that domain knowledge that's needed today, it's going to be in demand for 10 or 20 years. But if now it's going to be five years or fewer, then that's no longer the sole basis on which you should make a hiring decision.” Instead, she says, “We need to consider learning agility, growth mindset, adaptability. These are aspects that we need to consider because I don't want to hire someone to do one job for the next two years; I want to hire them for the ability to do the next five jobs over the next 10 years, and I have no idea what those jobs are going to be. They may be in skill areas that we don't even have the names for today.” As we talked with executives and hiring managers, we've come to see that traditional understanding of roles—full time, part time or temp, manager or rank and file, and the like—don't position organizations for maximum flexibility. After a lot of exploration, we identified five types of talent that each work in and contribute to organizations is specific ways (Figure 11.3), The talent types—executive producer, transformational, contingent, rotational, and foundational—each play a different role in the organization. Executive producers, for example, tend to be more project based, bringing specific expertise to coordinate a team to deliver a specific outcome. Contingent workers participate with an executive producer to bring specific skills to the project on a short-term basis, leaving the project when their contribution is delivered. These workers may be full-time employees of a company, moving from project to project, or they may be more loosely tied to the organization, on call as consultants or freelancers in an arrangement that gives maximum flexibility to both the organization and the individual worker. The television and movie industries have long engaged talent on a per-project basis, assembling the array of talent—from script writers to set designers, actors to accountants, directors to dolly grips—in order to bring together a Hollywood-style production. Increasingly, this engagement model works across all forms of business. Expertise, and the flexibility to apply it as needed, is the key principle at work here. LinkedIn cofounder and now Silicon Valley investor Reid Hoffman dubbed these short assignments “tours of duty” in a 2013 Harvard Business Review article cowritten with Ben Casnocha and Chris Yeh. It's a model that requires all of us to think differently about affiliation and retention on both sides of the employer–employee relationship. Figure 11.3 Types of Talent Sources: Reid Hoffman (foundational, rotational, and transformational talent) and Heather E. McGowan (contingent and executive producer talent). If you've been in the workforce for any time at all, you know that all your instincts ask what you will do in a job. What tasks will you be responsible for doing? How will you be expected to get the work done? How will you prove that you have the skills necessary to do the job? Hiring managers answer those questions when they write a job description. Leadership reinforces those answers when they organize their teams. If we are going to hire workers who show the adaptive resiliency to continuously learn and embrace change, we have to ask different questions. Pymetrics emerged as a company to help employers look for, and look at, candidates beyond job descriptions and resumes. Looking at movie recommendation systems like those used by Amazon or Netflix for inspiration, the company developed a deep analysis of both jobs and individual experience to harness “the power of the long-tail [of data] to match people to the jobs where they were most likely to succeed,” the company's website explains. Today, companies as diverse as fast-food chain McDonald's and mineral and mining conglomerate Rio Tinto use Pymetrics to better hire the most appropriate candidates. We reached out to Pymetrics founder and CEO Frida Polli to talk about the challenges of recruiting for adaptability and learning. When asked specifically about the challenge of finding talent, Polli responded, “I don't think it's because we don't have the people that can fill that role,” she told us. “It's because you're not evaluating them properly. If you're evaluating people based on the resume, that's a mistake. The resume is basically a backward-facing, static document that tells you what someone has done in the past. It tells you nothing about what they can potentially do in the present or in the future.” Instead of asking what a candidate has previously done or even what they can do, we have to talk about how potential employees think, how they see themselves, the vagaries of the job, and how they might see themselves in our organization. We need to toss aside the template that lists title, responsibilities, qualifications, and preferences in favor of one that enables applicants to see themselves in service to the mission of the company. We have to describe jobs not as a set of tasks, but as a series of tours in which people apply their experience and expertise, build upon that foundation, and then move on to new applications and learning in continuous cycles. Because our job role, if it exists at all, will inevitably change, we need to focus on our alignment with the company's values and our fit between leaders and teams. Chapters 9 and 10 discuss further how to do these things. Let's examine a little more closely what's wrong with most job descriptions and what might be done to better connect applicants with organizations. Most job descriptions begin by outlining what would be required of the applicant. And let's be honest, even organizations with the most foresight can only predict what might be required in any position across 12 or maybe 18 months. Instead, start with describing not the job, but your organization. Make your mission and values clear. This statement serves as both a magnet to attract the applicants who feel kinship with your mission and a filter to screen out those who have no affinity for the work you do. Consider this posting from a digital media startup where Chris serves as chief operating officer and used this language to recruit a top-notch marketing executive: About Us: We are a digital media company that leverages the power of storytelling to engage citizens more deeply with their communities, believing that everyone has the power to start something good … We are seeking a Head of Marketing to drive brand awareness and build a deeply engaged user community around our mission … The posting goes on to describe the ideal candidate, instead of the functions of the job. Sure, you want to hire someone with a proven track record, but, more importantly, you're looking to hire someone with something to prove. About You: You are a marketing genius and you're ready to prove it in a challenging, high-growth market. Your work has touched on many aspects of marketing—branding, social media, audience attraction and engagement, and market metrics—and you're looking for a place to bring that experience together to make a huge impact on a growing startup. You work hard, know your stuff, and deserve to be recognized and rewarded for it. You don't need to be micromanaged because you have a big vision and are motivated to turn ideas into action. You are eager to contribute your unique talents in a collaborative effort to bring a world-class media property to reality. Most importantly, you stand ready to lead in a dynamic environment where every day brings new opportunities and challenges. As important as it is to develop the strategy, your best work will come when you inspire, empower, and enable your team to deliver it. Rather than speaking to credentials, past experience, or demonstrated skills, this description addresses the aspirations of the applicant. It gives them the opportunity to see themselves in the job. As importantly, it makes very clear that the company will hire someone who can lead, rather than manage, a team. That's a critical distinction. Managers direct a process, they tell workers what to do, and, often, how to do it. Leaders, on the other hand, are catalysts for good work. They inspire people to do their best work and they provide the direction, resources, and coaching to deliver it. In times of change—and face it, it's all change now—you want to hire leaders, not managers. Finally, the posting talks about the job; not just the requirements of the job, but how the company expects a winning applicant to embrace the job. About the Job: A super-successful digital media company lives or dies on sustained attention—user attraction, retention, and engagement with its content. Our company wants to hire a thoughtful, talented, unique-thinking head of marketing who will be responsible for establishing and implementing the company's product growth and national roll-out strategy. You will own marketing across the company, working collaboratively as part of the company's leadership team, and ultimately building a first-class team of digital and brand marketing pros.

Our head of marketing will have experience with product marketing, brand engagement, social media, budget management, and digital media, and is eager to take that experience to the next level and beyond. Our head of marketing embraces experimentation (growth hacking) and does so with a discipline that respects metrics and deadlines. We will hire someone who is as comfortable working independently as collaboratively, who communicates easily with team members, accepts feedback and critique as tools to improve, and most of all is ready to grow into an exceptional and critical member of our leadership team.

We have no bias for degree or specific experience, and we absolutely respect and expect to hire someone with intelligence, self-awareness, motivation, and ambition. We are moving quickly, so you will need to show that you can think creatively, deliberate clearly, and move decisively. We expect your prior work and current interests to represent what you can do for us. Most of all, we hire people who prove themselves through their work, and who share our ambition to create the world's largest digital-first news platform. It's not a typical job description, to be sure, but it does hold up a mirror for potential applicants to see themselves working in that organization. Please, consider the text as a template for your organization if you like. We offer it with empathy because breaking old hiring habits is really, really hard. We're accustomed to defining the repeatable and measurable aspects of most jobs—“The successful candidate will have demonstrated product marketing skills,” our job descriptions might say—but we forget to talk about how those skills might be applied differently or how they might even become outdated in a world where marketing trends shift overnight. We're comfortable asking for Ivy League credentials or a platinum brand experience, but much less at ease trying to understand how those experiences mesh with the workplace we aspire to have. To help that process, Frida Polli's Pymetrics developed a matching platform that pairs jobs and candidates based on less tangible attributes of both the role and the worker. Using company data to identify the attributes of high performance in a specific role, the Pymetrics platform puts candidates through a series of tasks to assess a candidate for those attributes. Being careful to remove bias from the system, Polli told us her clients are better able to place high-quality candidates in jobs where they have a higher probability of success. One surprising outcome of the Pymetrics platform was that hiring diversity improved significantly. One aspect of that diversity was a drop in new hires with Ivy League credentials—often the presumptive proxy for a highly qualified candidate—as the platform identified highly competent candidates without prejudice for degree or affiliation. If we are to build adaptive teams, we have to start with adaptive hiring requirements. What might it mean to hire a really, really smart and intuitive person who's not graduated from college? How might someone with a deep passion for your market and customer overcome a deficit of experience you profess to look for? In our experience, we've found that it is often that person without a fancy degree—or any degree at all—who delivers amazing performance. They have to overcome a bias for credentials, work hard, and prove that they can get work done. More importantly, they bring a perspective that breaks from the homogenizing training of many elite academic programs. Stop and think about it for a moment. What do those prestigious degrees and flagship companies really signal? Prestigious degrees are often held by people who had a pathway to get them into the school the first place. So, does that degree signal someone who is especially high achieving or someone who is entitled? Or maybe both? Is experience at flagship brands really the most reliable signal when looking at a much larger pool of potential employees? Might longevity at an organization actually be a false signal of success when many times those with long tenures are best adept at organizational politics or, worse, fly under the radar by not challenging the status quo? The career signals that we've often used to identify candidates are as unreliable as they are reliable. By looking beyond conventional signals and tapping into unusual sources of talent, you're more likely to attract a phenomenal and diverse team. We cannot stress enough the power of diverse teams in the future of work. Too often, problem solving can be reductive as like-minded teams using existing knowledge to narrow, perhaps without even realizing it, possible solutions. We need people who are divergent thinkers to help us find and frame problems, then find novel solutions. Without sufficient “outside mind”—outside of what we've always done, outside what we were trained to think and do, outside the norms of the past—organizations will slip into a default mindset trying to frame and solve new problems by force-fitting old solutions on them. To be clear, we're not suggesting a criteria-less hiring processes. Rather, we're recommending that hiring managers embrace the idea that the need candidates fill today will be entirely different a year from now. The optimum thing to do, then, is to build flexibility and adaptability into the job description. The successful candidate will do X today and be able to pivot to Y tomorrow. This expectation builds adaptation into the job requirement. That's key when the future unfolds faster than we can predict. Make no mistake: it's far easier to write that far-ranging job description than it is to live and hire by it. Over the past few years, we've struggled to put a “future of work” lens on the team building of companies with which we've consulted. We might start with a forward-looking job description, but in the end, we get a mountain of resumes, thrown over the transom by people who just want a job with a stable organization. The easiest way to sort them out is to look at credentials and experience. So how is a modern business leader expected to build an adaptive future-resilient work force? Yes, screen for capabilities, and, as importantly, screen for fit. In fact, credentials and experience should be just the price of entry. Too often, “cultural fit” describes an employee who's happy to grab a drink after work, dress in a particular fashion, or bring her dog to work. We want to encourage you to rethink cultural fit to embrace candidates who think broadly and openly in the face of changing workplace dynamics. Cherish the interviewee who asks the probing question for which you did not have an easy answer. The best leaders don't hire for skills alone; they hire for mission and mindset while being open to candidates who make them a little uncomfortable because they think differently. They hire for cultural fit, knowing that many skills can be learned, but culture has to be felt and mission needs to be shared. What matters is whether the candidate can be “one of us,” where “one of us” means someone who can think, adapt, challenge, change, and grow. These abilities are paramount in the workforce that needs to find and frame problems not yet known. For that we need diverse and divergent thinking, creativity, curiosity, and talent that asks probing questions even when it makes us a little uncomfortable (Figure 11.4). Figure 11.4 Workforce of Yesterday versus Workforce of Tomorrow Hiring for fit requires a very different process, one that is inclusive of workers from across organizational functions. A hiring manager might have a pretty good bead on the capabilities of the ideal candidate, while potential coworkers can exercise their instincts as to a candidate's ability to cooperate and collaborate in line with the company culture. At Unreasonable Group, Epstein told us, hiring for culture is critical to the company's remarkable growth and scale. During the interview process, candidates are asked to consider various scenarios, each designed to elicit a response that reflects the candidate's alignment with Unreasonable's manifesto. “We try to bake in a way for our core values to show up,” Epstein says. In one such scenario, for example, a candidate was taken through a project where just about everything that could go wrong did. The goal of the exercise wasn't to see how the candidate would fix the problem, but whether she would own it. The goal was to see if the candidate's values aligned with the company's core tenet that states in part, “We push for open communication even when it's tough, whether that means being transparent about our failures publicly or creating the conditions for authentic communication within our teams.” By the time someone is hired at Unreasonable Group, they have talked to at least five teammates. “We have a final huddle to decide who we are going to hire,” Epstein says, adding that as much as they discuss qualifications they also “walk through how it feels” to engage with the candidates. The risk of hiring for cultural fit, however, is that over time your team becomes very homogenous, particularly when an organization perceives “culture” as style over the substance of its values. Epstein admits to making this mistake in the early days of Unreasonable Group. “I hired people close to me, people I knew and had fun working with,” he told us. Today, Unreasonable Group hires for “cultural add,” Epstein says. Cultural add, he explains, starts with alignment with the company's core values and then looks to see if a candidate is “bringing something new to the team.” If the hiring process at Unreasonable Group is a trial run of sorts, the hiring process for leadership positions at Amazon is a labyrinth. The first stage of the online retailer's process is straightforward: job seekers meet basic qualifications and move to an interview stage, or not. But there's more to applying than sending a resume to a recruiter; applicants are asked to frame their qualifications and experience in the context of the company's 14 leadership principles. Like many of the best companies, Amazon puts their values—their leadership principles—on their website to make clear exactly what they are looking for in coworkers.1 (This kind of bold statement can both attract talent that aligns with the principles and enable other applicants to recognize they don't fit with the organization.) If you are passed to the initial interview, you'll meet with a hiring manager who screens for qualification and capabilities. In other words, the interviewer is assessing whether you can do the job. Clear that hurdle and you'll be asked back to meet with a number of Amazon employees, some of whom would work with you directly, and others of whom are really just there to assess if you fit in the Amazon culture. After a day of interviews, your candidacy could end in one of three outcomes: a recommendation to hire because you are both qualified and a fit, a recommendation to pass because you are either not qualified or not a fit, or a recommendation to put your candidacy on hold because you are a fit, but not right for this particular job. This is a considerable investment in the hiring process. While a longer, more involved hiring process may seem counterintuitive in the age of rapid change, this method allows Amazon to screen applicants for other adjacent jobs, knowing full well that what they had in mind when they started looking has probably changed. It is important to stress here, though, that culture fit doesn't have to mean building a team of like-minded people cut from the same cloth, hewn by the same experiences, and practiced in thinking the same thoughts. The concept of culture add, in fact, is essential if the company is to adhere to its core value of “global identity.” “We care that our team is reflective of what is happening globally,” Epstein says. “Culture add lets us give that value an actual identity.” The idea of culture add is “a lot like religion,” he went on to say. “Whether you're Jewish or Christian or Buddhist, or any other religion, you hold a core set of values prescribed by that religion. It doesn't matter what your race or gender or age or country is. Those things all bring diverse experience, while you still hold your core beliefs.” With practice, you'll begin to loosen your grip on branded credentials and instead seek hires who demonstrate the open-mindedness and adaptability needed to navigate a constantly changing work environment. You will find people who fit well with your culture without blending into a bland soup of compliant employees. Argodesign, a strategy and design consultancy with offices in Austin, Brooklyn, and Amsterdam, does just that. The company, one employee recently told us, values individual contribution to fuel their creative processes and deep engagements with a diverse roster of clients. We “hire adults and let them do their jobs,” one executive told us. The bravest of leaders go a step further. They hire not just open thinkers, but ones who are actively almost antagonistic. Call them “devil's advocates” or something else, but those who are able to shine a light on alternative points of view and can disagree without being disagreeable are cherished gifts in a fast-moving organization. These are the people who dare to question the status quo. They are the ones who see disruption and opportunity on the horizon. They are the ones whose voice, if allowed to be heard, can be the scouts of necessary adaptation. These workers bring cognitive diversity to your organization. They are the contrarians who check your blind spots and prevent strategic wrong turns … if you give them the psychological safety to do so. (If this idea doesn't resonate, go back and reread Chapter 9.) Often, we hear leaders talk about their “teams,” by which they too often mean the portfolio of people who work for them. In the context of work, we forget that “teams” are a collaboration of individuals, each bringing essential skills and perspectives to a project with the intent of delivering something bigger and better than anything they could do on their own. Where the teams of the past might have looked like a vertical reporting structure, modern teams swarm around projects and objectives, rather than traditional roles within reporting hierarchies. When workers come together to take on a business opportunity—bringing a new product to market, shepherding a substantial partnership, brokering a market relationship between product and marketing executives—they are leveraging the strength of teamwork to advance the interests of the business. These partnerships might well include skills and capabilities that at one time had been housed in organizational silos. To shift from the traditional organizational charts that previously channeled people into siloed functions to adaptive organizations, we must organize in purpose-built teams. But how? For decades, companies have organized by functions: engineering, marketing, accounting, and so one. Hierarchical structures pushed cooperation up and down the vertical structure in order to get anything done. Although that structure and its communications might have been tiresome for many, that top-down organizational structure worked in slow-moving markets. Now that the pace of change has accelerated faster than most companies can organize a meeting, hierarchical structures are far less effective. Consider your work environment, remove anything mentally routine or predictable (that is, much of the processing work), and you will be left with learning. That being the case, how would you hire, organize, and develop your talent to optimize learning and adapting? The answer, we think, is to organize workers into purpose-built groups to tackle specific challenges. They may work on a project over a period of months or even years in what LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman refers to as a tour of duty, a period of focused work framed by objectives and measured by outcomes. A worker might be involved in a particular mission for only a short period during which her skills are required, or for a longer engagement where a long-view perspective and deep and relevant past experience will be valuable throughout the life of the project. In this model, workers might be assigned to a product team with responsibilities for specific inputs and deliverables, even while they have a primary assignment to a functional department. One might be both a part of the company's accounting department and be deployed to identify revenue-sucking contract compliance breeches. To accommodate such fluidity between roles, agile and adaptive companies are organizing physical space and project management to engage diverse perspectives and necessary skills. At one product design consultancy for which Heather consulted, for example, each employee is organized into three groups. The first group is the person's professional discipline (e.g., engineer, marketing, design, etc.). The second group is their project work team (e.g., solving a client problem) and their assignment to this team will frequently rotate, meaning that they will be moved to a potentially entirely new project as the company determines best deployment of their capabilities as existing projects complete and new projects emerge. The third group is a research group, charged with scanning the horizon for new opportunities such as understanding the potential of the Internet of Things or autonomous vehicles, for example. By experiencing each group, workers bring a more holistic understanding to whatever task is at hand. Moreover, this structure is a catalyst for the socialization that breaks down clans and groupthink and aids the development of a bridging (action) network (Figure 11.5). Figure 11.5 The Shape of Your Network Matters Concept Credit: Anne-Marie Slaughter (author of The Chessboard and the Web) and Julie Battilana and Tiziana Casciaro (authors of “The Network Secrets of Great Change Agents” in the Harvard Business Review). This structure becomes especially important during times of change when closed or clan-like networks can become pockets of resistance. In their article, “The Network Secrets of Great Change Agents” for The Harvard Business Review, writers Julie Battilana and Tiziana Casciaro shared the story of the United Kingdom's National Health Service to illustrate the point.2 The giant, bureaucratic agency underwent a massive transformation process, putting a clinical manager—a doctor, nurse, or some other person with a healthcare background—in charge of each local implementation. The authors tracked 68 of these projects and found that the “personal networks—their relationships with colleagues—were critical” in the success of these projects. “Change agents who were central in the organization's informal network,” they wrote, “had a clear advantage, regardless of their position in the formal hierarchy.” In the early days of the Internet, TellMe Networks developed an early platform for telephone-based automated voice services. In their Mountain View, California, offices, founder and CEO Mike McCue decided as both a practical and philosophical matter that his growing employee base would work better together if they better understood jobs other than their own. In a retrofitted printing factory, TellMe organized its workspace around pods that accommodated three or five desks. As new employees started their work for the company, they could pull up a chair at any available desk. It was not unusual, then, for an engineer to sit next to an accountant who was next to a marketing guru. Through osmosis, if not direct intent, employees got a broader view of their company and the interdependency of different flows of work. TellMe, which was acquired by Microsoft in 2007, is not alone in this approach to an integrative and more transparent view of company operations. O'Reilly Auto Parts has its human resources staff tour every functional area of the business so that they can best understand the organization as they recruit new talent. PayPal has implemented a two-year leadership training program that functions a bit like a medical residency, rotating management candidates through the organization, expecting them not only to learn about these areas, but to cross-pollinate ideas from one group to the next. These models, while different, have the same effect. They give workers a holistic—and empathic—understanding of parts of the business that fall outside their immediate jurisdiction and help form the human relationships that enable workers to openly share ideas, concerns, challenges, and opportunities. Perhaps even more importantly, these open networks transfer tacit knowledge that is so essential to any organization. The often unspoken know-how that makes the organization work, tacit knowledge that lives in humans, is not easily codified, and, therefore, can never be automated. By intentionally organizing individuals to interact beyond the tasks, you may be helping spread tacit knowledge. Even the best team structures will fail if they are not rooted in fundamental business strategy. It is more than popular these days to talk about “diversity” as a human resources (HR) strategy. An HR-centric strategy might advocate for a racially, culturally, and generationally diverse workforce in order to reflect both the customer and market. That's progress, but it is not enough. Diversity, especially cognitive and cultural diversity, needs to become not just HR strategy, but broader business and corporate strategy. Study after study demonstrates that diversity of thought and cultural experience yields better business results than homogenous teams. A 2018 Boston Consulting Group (BCG) study found that “increasing the diversity of leadership teams leads to more and better innovation and improved financial performance.” In both developed and developing countries, BCG found, greater diversity in leadership resulted in higher earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT). Leadership teams with greater diversity had 19% higher revenue from new innovations and 9% higher EBIT than those with lower leadership diversity.3 Interestingly, though, in their paper “Teams Solve Problems Faster When They're More Cognitively Diverse,” published in the Harvard Business Review, Alison Reynolds and David Lewis uncovered what seems at first to be a contrarian discovery. After running hundreds of strategic execution exercises with executive groups, they found no correlation that proves that the more demographically diverse a team is, the more creative and productive it will be. To make sense of this finding, they decided to look beyond gender, ethnicity, and age to consider the impact of cognitive diversity, the differences in perspective and information processing styles. Reynolds and Lewis adopted a model developed by psychiatrist Peter Robertson that looks at knowledge processing and perspective. In knowledge processing, we depend on our existing knowledge or seek new knowledge to address a new situation. Perspective either relies on our expertise or seeks out the expertise of others. By plotting the results of their strategic exercises onto Robertson's matrix, called the AEM cube, Reynolds and Lewis discovered “a significant correlation between high cognitive diversity and high performance.”4 “Tackling new challenges requires a balance between applying what we know and discovering what we don't know that might be useful. It also requires individual application of specialized expertise and the ability to step back and look at the bigger picture,” the researchers concluded. “A high degree of cognitive diversity could generate accelerated learning and performance in the face of new, uncertain, and complex situations, as in the case of the execution problem we set for our executives.”5 Cognitive diversity is tricky; it's not visible in the way race, gender, and age are. Cognitive diversity is also a cultural challenge for organizations that “screen for cultural fit” when “fit” often means “being one of us” and “thinking about the world the way we do.” It's tremendously difficult—and, frankly, highly evolved—to bring contrarians into your work sphere. About this, though, Reynolds and Lewis advise leaders to “find someone who disagrees with you and cherish them.” In a follow-on article “The Two Traits of the Best Problem-Solving Teams,” published in the Harvard Business Review, Reynolds and Lewis combined their research on cognitive diversity with work on psychological safety. In this study, they found that to tackle volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) challenges, the teams with both cognitive diversity and psychological safety were the most adaptable and “generative” teams. These groups, they found, “treated mistakes with curiosity and shared responsibility for the outcomes.”6 In this model (Figure 11.6), Reynolds and Lewis identified four team types: defensive, uniform, oppositional, and generative. Defensive is when cognitive diversity and safety are low; folks think the same and distrust each other. Uniform is when folks feel safe because they share groupthink. Oppositional is when folks have diverging perspectives and thinking styles but in a dynamic that can lead to combativeness. And generative is when team members think differently but in a safe space that allows for divergent perspectives. By now, you shouldn't be surprised to learn that the optimal teams for accelerated learning, and in particular tackling VUCA challenges, are generative. They are most able to create a new framework in which to understand problems, generate new ideas, and devise new solutions. This sort of framework is essential in accelerated change. Figure 11.6 For Accelerated Learning, Seek Cognitive Diversity and Psychological Safety Source: Alison Reynolds and David Lewis, Using the QI Index, from “The Two Traits of the Best Problem-Solving Teams” in the Harvard Business Review. Now consider the 70–20–10 model of learning, we introduced in Chapter 9. In this model, 10% of learning is coursework or direct instruction, what we typically think of as “formal education.” The next 20% of learning occurs in shared experiences with others and 70% is learning that happens in the flow of work. By these definitions, 90% of learning is social and collaborative. Couple this with the rise in collaborative work, and the importance of psychological safety and cognitive diversity are even more clear. Demographically and cognitively diverse teams will make better and more productive decisions. They will also make mistakes. Leading these teams demands that you create a safe space for failure. When we spoke with theoretical neuroscientist and cofounder of Socos Labs, Dr. Vivienne Ming, she stressed the importance of the psychological safety we discussed in Chapter 9. “When it comes to workforce preparation and learning more broadly,” she told us, “we need to get much more comfortable with failure. Learning how to fail and pushing through it is a huge predictor of success in a job.” And, we would add, for teams. Dr. Ming contends that in pursuing productivity, efficiency, and scale, organizations have “designed failure right out of the system.” “If you want something that grows, changes, explores, and pushes boundaries, there's just nothing in the fields of AI that does anything like that right now … That's the unique value proposition of humans, and we have to rethink how we help more humans work through failure in the creative economy.” The best leaders are incorporating learning post-mortems into the feedback loops of every step of every project. At Unreasonable Group, for example, Epstein takes regular occasions to ask his team to provide feedback. He invites project participants to answer three seemingly simple questions: What worked? What could be better? What should we celebrate? Participants in turn share in a format of “I liked,” “I wish,” and—our favorite—“reasons to dance.” In a quick round robin, Unreasonable Group identifies and affirms what is working and commits to do more to reinforce that good work, identifies what could be better and immediately follows through to affect change and improvement, and finally gives team members a moment to feel joy and share appreciation for one another and their work together. Companies that are successfully navigating between the Third and Fourth Industrial Revolutions have invested deeply in workforce learning and enrichment because they understand that the future of work is lived in a state of continuous learning. Research by Willis Towers Watson found that “Ninety percent of digitally maturing companies anticipate industry disruption caused by digital trends, however, only 44% are adequately preparing for it.”7 In those that are preparing, consider the often-cited example of AT&T. The company was built with a workforce of people whose job descriptions detailed the skills needed to climb telephone poles and dig trenches to lay cables, operate a switchboard to connect calls, and manage the thousands of workers who made telecommunications work. Today, the company supports a workforce of more than 250,000 people who manage a cloud-based business requiring cyber security, data analytics, and other technology-dependent tasks, along with the labor-intensive work required to maintain a modern data network. That transition has been anything but easy, yet AT&T took the unprecedented step of investing $1 billion in learning and training programs to lead its workforce into the Fourth Industrial Revolution.8 Rather than only reskilling workers for new jobs, however, the company encouraged workers to pursue the learning that most interested them, leaving them with the potential to form new jobs around each worker's capabilities and experiences. Today, AT&T is much more than a telecommunications giant. Its acquisition of Time Warner in 2018, for example, puts AT&T at the center of media assets, including HBO and CNN. AT&T launched Xandar, a data-based advertising business, to tap into new revenue streams. As the company continues to expand from its traditional position, the investment in training and discovery reveals a business that recognizes that its staying power will be realized through learning. “We're working constantly to engage and reskill our employees, and to inspire a culture of continuous learning,” AT&T's William Blasé told us. “For us, the reskilling effort is about transparency and empowerment—creating learning content, tools, and processes that help empower employees to take control of their own development and their own careers.” In other words, AT&T didn't only train workers to fit into new job descriptions. Instead, they built a robust educational infrastructure with a predictive skills and knowledge dashboard that could allow for jobs that fit the abilities and interests of the worker. Just like at AT&T, future jobs will form around workers, rather than workers being plugged into job constructs built on a list of known tasks, knowledge requirements, and set capabilities. We have arrived at a unique moment in human history where more generations are participating in the workforce than ever before. Prior to the turn of the century, older workers, those the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) defines as 55 years of age or older, were the smallest segment of the labor force. Throughout this century, that age group's share of the workforce has increased as younger age groups have declined.9 Today, most organizations have four generations working within them, and the BLS projects that more than 10% of people over the age of 75 will be in the workforce in 2026.10 Managing a cross-generational team of individuals who variously grew up listening to Billie Holliday, Billy Idol, or Billie Eilish is a challenge, to say the least. That their cultural touchstones are so wildly different might make for challenging conversations … if they can find a common method to communicate at all. Communication is the foundation of collaboration in VUCA work. Those at the older end of the spectrum grew up with synchronous communications, either face to face or by telephone. Gen Z and Millennials grew up with mobile smartphones and quickly shifted from synchronous calling to asynchronous texting and a range of apps. And when they do engage in synchronous calls, they are comfortable with telepresence, using video apps of varying quality in preference to “in person” meetings. It may be challenging to lead a multigenerational force to collective collaboration, but the effort can pay off in spades. Older workers are the repository for much of the tacit knowledge of an organization, not to mention the wisdom that comes from the experience of developing tacit knowledge across a series of organizations. At the same time, the digital skills of younger workers are vital in a transforming economy. Together, these skills span the depth and breadth of knowledge to create the most formidable teams. (Figure 11.7) Figure 11.7 Five Generations in the Workforce Perhaps the biggest challenge in the future of work is imagining what that future might look like. Leaders might just have to take a leap of faith and invent a future organization that optimizes for adaptability over everyday reliability. Frankly, that old-fashioned “reliability” will become increasingly unreliable in the face of change. Just ask the former executives at Blockbuster and Kodak. We need to build teams with clear eyes focused on an unclear horizon, resisting the urge to stare into the rearview mirror and assume that what worked yesterday will be adequate for tomorrow. We need to optimize for sense making and risk taking rather than for efficiency of production. We need to build fluid work groups, rather than work structures. Groups will assemble for a task or project, then disassemble when that project is complete. Group members may be free agents for a time once the group is disbanded, and they will use their free agency to retool their skills and learning for the next opportunity. Or they may find themselves quickly recruited to a new work group project in need of the experience gained from the prior project. Workers really will work in teams, just not permanent ones. As important as inspired hiring and agile organization structures are in the new reality of work, inspired leadership is even more critical. In his book Excellence Wins: A No Nonsense Guide to Becoming the Best in a World of Compromise, cofounder and former president of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel company Horst Schulze makes this point clear. “There is no business,” he writes, “There are only people … Reading the economic forecasts and the indicators and the ratios and the rates of this or that, someone from another planet might actually believe that there are really invisible hands at work in the marketplace.” Leaders, he continues “are in the people game” and then makes a clear distinction: “Managers push; leaders inspire.” Make no mistake: hiring for capacity to learn, for alignment of purpose and values, and for an agile mindset is no simple task. Organizing and enabling teams for a future that is uncertain except in its potential for disruption requires dramatically new ways of thinking about work and workers. To put it bluntly, the future of work sets a new and very high bar for leadership. As marketing guru Seth Godin says, “Managers manage process and leaders lead change.” It is all change now, and that requires a shift from management to drive productivity to leadership to inspire human potential, as we discussed in Chapter 9. In the course of researching and writing this book, we spoke with dozens of researchers, organizational experts, and business leaders, asking each what they believed the future of work held. Those answers are woven throughout this book, yet it seems most fitting—most honest—to close this chapter with this insight from a conversation with Pymetrics’ Frida Polli. How, we asked her, can business leaders support and inspire their teams to their best and most fearless work? “Humans,” she said, “sometimes are very limited. They see a pattern. They just want to put a pattern onto the next 20 to 30 years. But, we have no idea. We literally have no idea what's going to happen.” In that context, our best advice is to buckle up. As leadership guru Jim Kouzes reminded us, “When you're moving fast, like a race car on a track, you have to have to pay more attention.” That attention will be your greatest tool in leading the Future of Work. That attention allows you to Let go. Learn Fast. Be Adaptable. And make it the future you want it to be.

No More Little Boxes

The Job Description Is History

Job Descriptions Become Traps

Fire Your Job Description

Hire for Cultural Alignment

Hire Adults and Let Them Do Their Jobs

Turn the Right People into Great Teams

Embrace Cognitive Diversity

Get Comfortable with Failure

Live in a State of Continuous Learning

Manage a Multigenerational Workforce

How Do We Get from Here to There?

The New Leadership Imperative

Notes