6

Finding the Courage to Let Go of Occupational Identity

Key Ideas In his seminal book The Practice of Management, Peter Drucker describes the parable of the three stonecutters: An old story tells of three stonecutters who were asked what they were doing. The first replied, “I am making a living.” The second kept on hammering while he said, “I am doing the best job of stonecutting in the entire country.” The third one looked up with a visionary gleam in his eyes and said, “I am building a cathedral.”1 Before you read on, think about your own work, then jot down which stonecutter sounds most like you. Drucker used the stonecutter parable to illustrate the importance of managers who see the bigger picture, are driven by a vision, and are not distracted by the means to that end. Drucker identified the first stonecutter as a highly manageable individual seeking a “fair day's work for a fair day's pay.” The third stonecutter, he wrote, was the true manager. The second stonecutter, he lamented, was the real problem. “The majority of managers in any business enterprise, are, like the second man, concerned with specialized work.” When Drucker's book was first published in 1954, managers believed that the best workers did not think, but instead just did what they were told. In that old economy, management wanted workers who did not think. Today, we need a different kind of workforce, one in which everyone is able to think, adapt, learn, and create new value for their organizations and themselves. In fact, that's what makes this parable—and its many retellings—even more relevant today. In one version of the story, the third stonecutter declares, “I am building a cathedral to bring people together.” In that version of the parable, the stonecutter reveals not just a vision—to build a cathedral—but also a purpose—to bring people together. And the first stonecutter, today, may be in the best position to adapt. His focus on “making a living” is untethered from any particular occupational identity. Even so, however, that worker's lack of connection to his work means he may not have the necessary motivational drive to traverse from one occupation or industry to the next unless the pull of making a living itself is strong enough. The second stonecutter, though, is in a world of hurt in the emerging world of work. He is entirely defined by the material, the job, the business model, and the industry. As we discussed in Chapter 5, identity tightly tied to a current job or an application of current and specific skills and knowledge is very dangerous when the world is moving rapidly around us. Instead, a purpose-driven identity—a sense of self that transcends job title and skillsets—is the best defense against work-related obsolescence. Yet, building that identity is not easy, because to have a sense of purpose, you must first discover your purpose. Annalie Killian, vice president of human networks at New York management consulting firm sparks & honey, described finding your purpose as “a lifelong process of experimentation and editing.” Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos famously signs his annual shareholder letters “two decades later, still in Day 1.” His point is that it is very easy to fall into routine. “Day 2,” he wrote in his 2017 letter to shareholders, “is stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death. And that is why it is always Day 1.”2 How do we avoid falling prey to occupational identity traps? We start with Why. A decade ago, at a TEDx event in Puget Sound,3 leadership guru Simon Sinek put forth a concept he called the “Golden Circle” in his talk “How Great Leaders Inspire Action,” This talk has been viewed by over 46 million people and is the third most watched TED Talk of all time. Sinek codified his observations in his best-selling book Start with Why,4 in which he posits that people do not buy What you do, they buy Why you do it. We are attracted to things, he says, but we are even more connected to shared purpose. At the outer ring of his Golden Circle, Sinek proposes that every organization—and, we would add, every individual—can tell you what they do. Companies offer some sort of unit of value, like a product or service. We define ourselves by what we do in our jobs, readily connecting to a title, industry, or set of responsibilities. Every company answers the What question easily. One ring closer to the center, though, the question gets trickier. Good companies, Sinek says, can also answer the How question. How do you create your unit of value? The answer is generally the special process, whether technical patents or human capabilities, that enables a company to deliver its What. Our How, as individual contributors, is our set of unique capabilities, something most of us are able to describe. Truly great companies, Sinek says, reach the center of the Golden Circle: the Why. These companies can tell you why they exist. They can explain their purpose and what they believe, at their core, to be true. They have a sense of mission that enables customers and employees to connect across shared values. In the age of accelerated change, every company needs to define themselves not just by their What or How, but also by their Why. The Why is the principle that guides organizations through rapidly transforming market requirements, product and services opportunities, and business model adaptation. The Why is every company's unique advantage. Consider Amazon and Barnes & Noble, both booksellers, but with different Whys. In response to Amazon's market entry, Barnes & Noble began selling books online as well as in its brick-and-mortar stores. Amazon determined its Why “to be Earth's most customer-centric company, where customers can find and discover anything they might want to buy online, and endeavors to offer its customers the lowest possible prices.5 Amazon became a massive retail presence with offerings that span streaming media, entertainment content, drones, consumer technology, healthcare, and industrial cloud services. Barnes & Noble, focusing its Why on serving book lovers, remains largely a brick-and-mortar retailer with some online presence and modest forays into adjacent markets such as toys, games, and stationery products. Where you shop for books likely depends on your specific needs, but you can be pretty sure that Barnes & Noble won't be winning an Academy Award or providing your healthcare (Figure 6.1). Figure 6.1 Amazon's Why, How, What As technological and social change unmoor us from our professional identities, we must connect to our Why as well. If the research reported in the Foundation for Young Australians’ seminal paper “A New Work Mindset” is correct, young people in the developed world graduating today will likely hold 17 jobs across five different industries in the course of their careers.6 To navigate that trajectory, you cannot define yourself by what you do. Instead, you must take your definition from how and why you do it (Figure 6.2). This search for meaning is a lifelong process of negotiation and experimentation. Experimentation allows you to try out versions of you and edit until you zero in on things that matter most to you. These versions will change over time, each being a chapter in the book that is your career. We loved the way Kate O'Keeffe, founder of the Cisco Hyperinnovation Living Labs (CHILL), expressed that idea to us: “We need to stop thinking about ourselves as forming a finished product and we need to start thinking of ourselves and our careers as a prototype in continual states of change and improvement.” That continual state of change is the adaptation advantage at work. Figure 6.2 Purpose First, Job Last: Your Why, How, What By thinking of your career as a continual “beta,” you will develop your relationship to purpose, better understand and develop your superpowers, and come to recognize that your job is merely the application of your skills and a connection to your purpose at a moment in time. This is how you move from “a fair day's work for a fair day's pay” (stonecutter 1) or a fixation on your current tasks (stonecutter 2) to a greater purpose-driven vision (stonecutter 3), “building a cathedral to bring people together.” Exercise 1: Your What, How, Why Describe your career in the What, How, and Why framework. Consider all your Whats or at least the most import ones—the jobs that were most meaningful to you, the ones where you felt like you were firing on all cylinders, expressing your true self. Then, try to capture your Hows—consider the things you believe you do well and ask yourself what your unique abilities and aptitudes are that make you good at what you do. Finally, think about your Why. Your Why is what drives you. You do not necessarily need alignment between your Why and your employer's Why, but it does help. (If you need help with your Why, go to Exercise 2.)

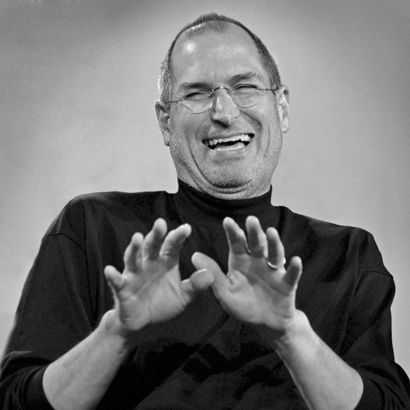

Exercise 2: Passion and Curiosity Inventory Finding your passion sounds simple but figuring out what motivates you and aligning that motivation with market opportunity may be one of the hardest, and most important, tasks in navigating your career. Try starting with a simple exercise: journaling. Keep a journal for at least a week or two and maybe a month if you can manage it. Enter your activities for the day every day. Once you have finished your list of things you've done that day, review the list and circle the things that gave you energy. Note the tasks, meetings, conversations, or anything else that you could not wait to tackle. Capture the thoughts and ideas that entered your mind as you woke in the morning and would not leave your mind as you sought to sleep at the end of the day—not the things that haunted you and stressed you out, but the things that you generally enjoyed doing. Can you aggregate these things and synthesize them into a single statement or two? This can be a daunting exercise, so it's only fair that we take you through our own experiences as examples. Heather has a background in industrial design (product design, design thinking) and an MBA with a concentration in entrepreneurship. She likes finding a pathway through ambiguity by researching, asking questions, synthesizing information, and visualizing the resulting complexity to provide a clear plan of action. She currently applies her design and business skills (her How) by crafting keynote talks (her What) that allow her to realize her Why of continuous learning. Heather does not want routine. She does not want to go into an office and do the same thing every day. Her job as a keynote speaker takes her all over the world to all sorts of companies and organizations, keeping her on a continuous and steep learning curve with frequent opportunities to experience and adapt to new and different cultures. That work energizes her. The rapid rate of change means business leaders, educators, investors, policy makers, corporate governors, and many more folks are trying to make sense of the shifting opportunities for their organizations. That's a rich market opportunity for Heather. Prior to this work she engaged in consulting, ranging through product design and design strategy, socially responsible investing, educational consulting, and corporate consulting—each also providing a continuous and steep learning curve with a high need for adaptation. Chris has always seen her work through the eyes of a journalist. She is an observer, a reporter, an analyst of situations, and a communicator of ideas. Early in her career, she jumped into the tech sector, applying her craft as an editor, largely focusing on new personal computing products and, specifically, on the sector's startup companies. She quickly understood that technology had tremendous potential to transform society and wanted to champion its use for good (her Why). By listening to and interviewing more than 20,000 startups, Chris discovered that her superpower is connecting the dots among people and ideas, seeing patterns that others often miss (her How). Today, she consults with select startups, curates a community of journalists, and writes about emerging ideas (her What). The US Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that 1.5 million involuntary and 3 million voluntary job “separations” occur each month. The problem is not limited to the United States. In just about every part of the world, job loss and job change are the new normal. It helps no one to act as if they're not. Losing a job is hard. It can be devastating financially, socially, and personally to lose your place, your status, your sense of self, and the financial stability that supports your primary relationships. As Chapter 5 discussed, overcoming job loss can be more difficult than getting past the loss of a primary personal relationship. Sometimes, though, job loss and change can be a gift. You can, if you allow yourself, learn the most in these hard moments and find ways in the end to liberate yourself from the constraints of your past occupational identities. Although he was asked many times, Steve Jobs (Figure 6.3) only gave one commencement speech in his life. In his speech to the Stanford graduating class of 2005, his honesty and vulnerability provided great insights into the gift of job loss. The world's most famous CEO, the modern Ben Franklin, had been fired. What he said about that experience is remarkable.7 Figure 6.3 Steve Jobs Photo © Asa Mathat. In what is widely recognized as one of the best commencement speeches ever given, Jobs talked of the early success of Apple, growing the company from a workshop in his family's garage to a $2 billion enterprise in just 10 years. At about that time, Jobs recruited former Pepsi-Cola CEO John Sculley to work with him as Apple's CEO. What started as a great collaboration turned into a greater conflict. The Apple board took Sculley's side, and Jobs was out of the company he created. “So at 30 I was out. And very publicly out. What had been the focus of my entire adult life was gone, and it was devastating,” Jobs told the Stanford graduates. “I didn't see it then,” he said, “but it turned out that getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods of my life.” Jobs's story is the stuff of legend. In addition to NeXT, he started the animated movie company Pixar, which created the first fully computer-generated animated film, Toy Story, now one of the top-grossing animated film franchises ever. In a twist of fate, Apple bought NeXT, and Jobs returned to Apple, ultimately reclaimed the CEO's office, disrupted the music industry by bringing the iTunes and iPod products to market, and supercharged the smartphone market by introducing the iPhone. “I'm pretty sure none of this would have happened if I hadn't been fired from Apple,” Jobs recounts in his speech, adding later, “I'm convinced that the only thing that kept me going was that I loved what I did.” His advice for the Stanford graduates is excellent advice for anyone: “Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do.” Like most of our readers, we authors have both experienced the tough love that comes from disconnecting with occupational identity. We want to share our stories in the hopes that you might learn from them. What's more, it's reassuring for all of us to recognize that this is a shared experience that we are growing through together. Recently, I was asked what metaphorical mountain I had climbed in my career. I was stumped. For much of my career, I didn't see mountains; I just forged ahead, doing the work and taking on challenges that, in aggregate, looked like a well-intentioned career as a technology journalist turned startup guru turned author. I began my career almost accidentally, taking a job in a publishing company while waiting to begin graduate school. Soon, the job was much more interesting than the prospect of more school and I surrendered my fellowship to dive into work. Over time, I rose to editorial leadership positions at the top technology publishing company, ran the industry-leading startup showcase that ushered some 1,500 startups to market, and launched my own startup event and advisory firm. For nearly 30 years, my professional identity was wrapped up in that work and I was widely recognized for it. But the underpinnings of my company weren't as strong as they needed to be. In the parlance of the startup world, we pivoted from event producer to software platform to a co-working space, and we never got enough lift to really soar. At the end of 2012, I closed the business, and without realizing it, largely closed a chapter of my career without knowing the plot of the next one. What unfolded over the next five years is truly the biggest mountain of my career. Actually, “quest” might be the better word. In that time, I had to face the question “Who am I if not who I was?” I needed to be brave enough to shed an identity that no longer fit and to find comfort in a new self-definition. I grabbed at new experiences like a sailor hugs a mast in a storm, anything to find safety in the midst of deep change. I took a turn at seafaring (literally), where I mentored social-impact entrepreneurs aboard a ship circumnavigating the globe. I spent an academic year in a journalism fellowship, then got and then lost a job at a world-class academic institution. On a lark, I even tried bartending school and experimented with the gig economy, driving for Uber and working through UpWork and Thumbtack to better understand the experience of all three. None of it made answering the question “What do you do?” any easier, but all of it got me closer to articulating the Why of how I spent my working capital. Each of those experiences taught me something about myself, and collectively they taught me the value of intentionality, about doing work not because it was something to do, but rather because it was the thing to do. I learned which work gave me purpose, which did not, and most importantly, how to say no to work that took more than it gave in satisfaction and learning. Learning to work with purpose and intention sounds like it should be the simplest thing in the world. It is not. In fact, it's been the hardest work of my long career. I have three hard lesson stories: rejection, a firing, and feedback. All three have informed my life every day since. In my twenties, I had somehow managed to avoid failure. Somehow everything I had truly wanted had materialized. In high school sports, I had been varsity, captain, and all-star. I was accepted into the college of my dreams, Rhode Island School of Design. After a couple of professional jobs in design, I was repeatedly told I was asking inappropriate questions about why we were pursuing certain products or markets. That, I was told, was the domain of “business” and if I wanted to ask those questions I ought to get an MBA. Okay, roger that. I figured I would just go to an Ivy League school and pick up an MBA. My presumption of privilege was off the charts. I took the required standardized tests and got hard lesson number 1: I scored 440 out of a possible 800. I buckled down, studied endlessly, tested again, and received a 700. Good enough. I applied to all the top business schools. To my surprise, rejection after rejection arrived. One admissions counselor told me, “Frankly, we do not have any idea why you want to study business if you studied art and you work in design. Maybe this just isn't for you.” Finally, after admissions season, I applied to Babson College and was accepted. The funny thing was that I received a rejection letter from a school I had not applied to that year. It was like they wanted to send the message: “Seriously, Heather, it is never going to happen, so we are now sending you a ‘don't even think about it’ preemptive rejection.” I went to Babson, which turned out to be the exact right place for me. Entrepreneurial thinking is a perfect complement to design thinking. Design thinking helps you find and frame problems; entrepreneurial thinking helps you scale solutions and create value. This is my first hard lesson story. Hard lesson number 2, unfortunately, came around the same time as the first hard lesson. I was fired. I was treading water at that large sporting goods company and they decided I was far more trouble than I was worth. I was arrogant, angry, and lacked the maturity to process the business school rejections I had been receiving. Frankly, I also was not very good at this kind of design and I cared little about it. Technically, I lost my job in a downsizing, but I made myself an easy target for cost savings. Still, I was stunned. I was deemed no longer relevant. Making sense of this took some time. On the one hand, I was lucky, because I transitioned immediately into consulting work and fairly quickly and easily picked up enough consulting work to keep myself afloat. On the other hand, design was my job. How did they get to decide I was suddenly no longer needed with no notice and little financial runway? Suddenly I lost my daily routine, work identity, and face-to-face interaction with my work friends. It took me a few years to fully appreciate this experience, but losing my job and then building a consulting practice taught me to create new value every day, for myself and for any organization that engages me as a consultant or a speaker. Every moment of every day, I strive to provide maximum value to the organization. I never take that for granted. I only work for places that share my values, which makes it easier to concentrate on creating value for those organizations. Hard lesson number 3 was simpler, but no less impactful. As a young consultant, I joined forces with another much more seasoned and successful consultant who had his own well-established firm. I had an idea for a product for the medical industry, which was his specialty. Together, we pitched my idea to a very large company. After the pitch meeting, the senior consultant took me aside and offered me advice. I was young and not nearly as self-aware as I should have been. I was not expecting a critique. In fact, I might even have been expecting a compliment. I had run much of the meeting and thought I had done a pretty good job. He said, “You are smart, and you have some really great ideas, but you have absolutely zero idea when people are no longer listening to you. You are clueless about your audience. It would benefit you to pay much closer attention to your audience and cater your message, rather than focus on telling every detail you deem important.” I was a bit stunned but pretty quickly realized that this was really valuable feedback I could do something with. I have thought about that feedback frequently over the 20 years since it was offered. I have written a few times to my senior colleague, now long retired, telling him how much his candor meant to me because it quite literally changed my life. I make a living now as a speaker, which I am quite certain would not have happened if I had not learned how to connect and communicate rather than simply spew my talking points on whatever poor souls landed in front of me. So for me, hard lesson number 1, rejection, taught me that to find my fit is far more important than prestige lists. Hard lesson number 2, the firing, taught me to create new value for my clients every day. When I can no longer create new value, I should move on to my next challenge. And hard lesson number 3, feedback, taught me to speak to my audience's interest, not my own. I am very thankful to the person who fired me, the many admissions counselors who rejected me (as well as the one who accepted me), and Jack, my consultant friend who was generous enough to give me a hard and much-needed message. Exercise 3: Learning from Hard Lessons What are your hard lessons? What are the most difficult things you have experienced or endured and how have you learned from them? If you need more inspiration than our or Steve Jobs's stories, we suggest a couple of TED Talks. No matter what you might think about her now-infamous White House internship, Monica Lewinsky's life has been defined by a very public lapse of judgment in her early twenties, and for it, Lewinsky has been a target of cyberbullies and unflattering press. Few others have faced such harsh and public repercussions for their errors in judgment. And few have had to do the work Lewinsky has done to process that experience. We highly recommend her TED Talk in which she gives a clear path forward to anyone who's suffered deep shame. In another recommended TED Talk, the mother of Columbine High School shooter Dylan Klebold shares her struggle to make sense of raising a son who becomes a murderer. Sue Klebold has become involved in medical research and brain science to try and help prevent future tragedies. If these two women can emerge from their experiences you may be able to as well. Think about this exercise as creating a TED Talk about your hard lesson. How do you make sense of it? What did you learn from it? What lessons or gifts were contained in the bad-tasting medicine you received? So now it is up to you. What kind of stonecutter are you? How do you define your Why and How? How does your What manifest your Why and How? What is your purpose? Pay attention to what interests you; that is the fuel source for your lifelong learning and the basis for your adaptation advantage. In fact, the answers to these questions will give you the courage to let go and thrive.

What Does the Parable of the Three Stonecutters Have to Do with You?

The Day 1 Mindset: You Are a Prototype; Start with Why

How Job Loss Can Be a Gain

Modeling Vulnerability: We Share Our Hard Lessons

Chris

Heather

What Do You Do Now?

Notes