10

The Adaptive Organization: Creating the Capacity to Change at the Speed of Technology, Market, and Social Evolution

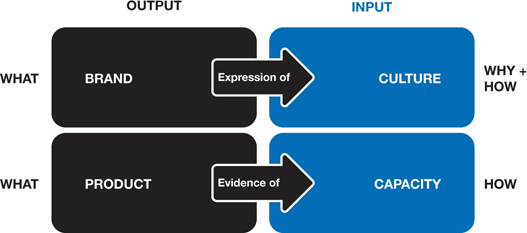

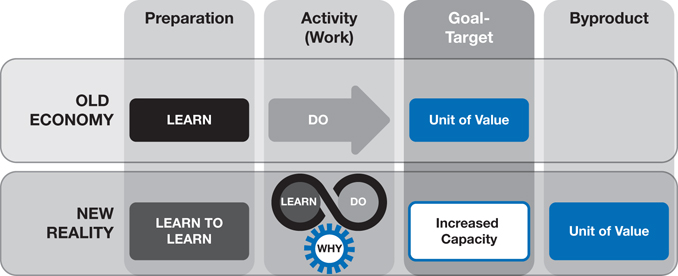

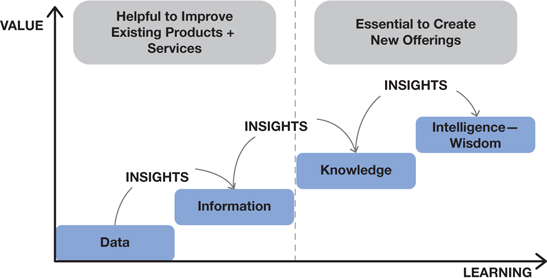

Key Ideas When William Muir set out to study productivity, he used hens as his test subject because measuring their egg-laying productivity was simple. She who lays the most eggs is the most productive. (If you skipped Chapter 9, you'll want to go back and give it a quick scan to learn more about this intriguing experiment.) For much of the Second and Third Industrial Revolutions, we measured human productivity in the same way. Count the number of acres plowed, the cars produced on the line, the barrels of crude pulled from the earth, the new accounts opened, or the clicks and page views on a website, and you get a measure of productivity. But what if, in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, we are measuring the wrong things? Does optimizing the production of Product A matter as much when market winds shift to Technology B before you can even complete an inventory of the first? What if production output matters far less in the future of work than does production process? What should we measure then? That's the conundrum for many organizational leaders as they rethink how they construct and lead their teams for greater learning and adaptation. Fortunately, Dr. Muir's productivity experiments light the way. Recall that in Muir's experiment the “super chickens”—the hens that were the most productive layers—were also the most caustic. They outperformed their peers by intimidating, abusing, and in some cases even killing them. In short, the super chickens were bullies. They looked good because they made others look bad. While attempting to foster a breed of high-performing hens, Dr. Muir inadvertently gave us a lesson in the importance of culture. The toxic “work environment” inside those cages didn't just kill chickens, it killed productivity over the long term. Similarly, as Dr. Muir found, the best environments fostered productivity. When Dr. Muir selected all the hens—and not just the top performers—from the best-producing flocks, productivity increased 160%. As we cross the bridge to a digital economy, we need to shift from measuring output to optimizing throughput. In other words, the conditions in which we create and produce will matter more than the product itself. That may sound like a radical idea, but consider this: the things we produce—because they may be transient—are a product of our organization's capacity to identify and rapidly respond to new opportunity and capture new value. Products and services will be short-lived. Rather than optimizing for specific production, our best work will be in establishing the conditions that enable continuous and continually shifting methods of value creation. These conditions result in an agile, learning, and adaptable company able to thrive in the new realities on the other side of the digital economy bridge. Those conditions we call culture and capacity. It's a radical but remarkably straightforward concept: companies are nothing more than culture and capacity. Period. Of course, neither culture nor capacity is a simple construct. Still, if you can break apart these two elements to understand them, you can rejoin the ideas to create a framework for highly effective organizational leadership. So, let's break it down. When we put culture and capacity together, we create a powerful force for transformation of the business, one that shifts the focus from output to input. Culture and capacity are the conditions—the inputs—of an effective business. To the outside world, culture shows up as a brand, an expression of the company's purpose and values. Capacity is evident in the products and services a company puts into the market; these products and services are the outputs of an organization's ability to learn and create (Figure 10.1). Drop culture and capacity into a market context—a market need, an industry, a geography—and you have a business. To put culture and capacity to work in our organizations, then, we need to better understand both. Let's dive deeper. Figure 10.1 Focus on the Inputs: Culture and Capacity Every organization has a culture. Culture is a sense of purpose and a way of doing things that structure daily life at work. Over three decades of observing culture in early-stage technology companies, Chris developed a theory: culture is either intentional or accidental. An intentional culture is a deliberate construction of organizational leaders, created in collaboration with all those who are led. An accidental culture is an environment that emerges without intention from a collection of experiences. Accidental cultures, Chris has observed, are almost always toxic. Too often, the trappings of a workplace—onsite daycare, free gourmet meals, dog-friendly offices, and the like—are mistaken for corporate culture. At best, these benefits are evidence of a culture, but they are not the culture itself. In an intentional culture, a company might declare a lofty purpose: to “unlock human creative potential,” for example. Among its operating principles might be a statement like “We believe our employees are at their best when they are at their healthiest.” Dozens of decisions can extend easily from that statement of values, allowing the company to say yes to an onsite gym and no to junk food–stocked vending machines. The workplace benefit reflects the values, rather than the other way around. If that's not clear, let's try another example. You walk into an office space and notice that every desk is outfitted with a Herman Miller Aeron chair, list price $969. These ultra-comfortable, highly ergonomic chairs were once all the rage with well-funded Silicon Valley startups. What do they say about the company's values? On the one hand, it might project a core belief that employees are most productive when they have a comfortable work environment (intentional). On the other—as is too often the case in the profligate boom cycles—it might just mean “we raised a lot of money and we're spending it on ourselves instead of on our business objectives” (accidental). Like we said, the workplace benefits reflect the company values. Intentional culture begins with organization's leadership. Frankly, it is organizational leadership. So, where do you start to build a great culture? Author and leadership guru Simon Sinek delivered one of the most watched TED Talks of all time, “How Great Leaders Inspire Action.” In this brief talk, well worth the 18 minutes to view, he reminds us that transformational leaders of all kinds set clear targets. From Martin Luther King Jr.'s leading the civil rights movement to the Wright Brothers’ chasing the dream of flight, great leaders craft a big vision and give their people a reason to follow them. We join our efforts with great leaders because we share a sense of purpose and live by common values. Or, as Sinek would say, start with why. The center of every great culture is a clear sense of purpose. One young company that has identified its purpose with unmatched certitude is Unreasonable Group. Born from a series of pilot projects and experiments, Unreasonable Group has always had a clear-eyed purpose: “to create a world in which the most valuable and influential companies of our time are those solving humanity's most pressing challenges.” Unreasonable Group runs immersive development programs for growth-stage companies building solutions to “seemingly intractable challenges,” from alleviating poverty to reversing climate change. The organization partners with global companies as diverse as Nike and Barclays because it is dedicated to driving resources to and breaking down barriers for entrepreneurs who solve the biggest problems. That sense of purpose runs through everything the company does. Even its name—Unreasonable Group—comes from founder Daniel Epstein's sense of purpose to change the world. “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world,” George Bernard Shaw wrote in Man and Superman. “The unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man”—“and woman,” Unreasonable Group adds to its appropriated mantra. About three years into building the company, Epstein realized that as the team and community grew, they were rooted in purpose and operating from shared values, but “if we were ever going to have a chance at scaling culture, our values needed to be articulated and expressed in a way that resonates with us,” Epstein told us. “Codification of those values is remarkably important. Not just to feel, but to point to. We took what we were living by and put it into words.” Now, the Unreasonable Group's manifesto is front and center of everything the company does (Figure 10.2). We think this is the most important webpage we've ever built. Unreasonable, from its inception, has been a values-driven organization. To be clear, the manifesto below is not a gimmick. All our moves are guided by the constraints set within our values. Without them, Unreasonable Group wouldn't be Unreasonable. WHY WE EXIST Our mission is to drive resources into and break down barriers for entrepreneurs solving BFPs. Our vision is to create a world in which the most valuable & influential companies of our time are those solving humanity's most pressing challenges. Below are our values but we want to make clear that we have one law: entrepreneur-centricity. Come hell or high water, we exist to support the entrepreneurs that make up our global community. OUR VALUES LONG TERM > SHORT TERM We put an emphasis on long-term value and impact over short-term gains. In fact, impact is the sole reason we do anything & everything. It is our only bottom line. Although we believe in the power of profit to drive lasting and scalable change, when evaluating an opportunity, we examine its worth via the depth and breadth of the impact we envision possible. CLIMB THE RIGHT MOUNTAIN The speed at which you climb the mountain is important, but only relevant if you choose the right mountain to climb. Effectiveness is more important than efficiency and it needs to be intentionally measured over time. We constantly ask ourselves if we are climbing the right mountain and look to leverage data to ensure we are on course and heading towards the chartered summit. Read more about this value on Unreasonable.is. NO BULLSHIT We believe humility is paramount and we view vulnerability as strength. We push for open communication even when it's tough, whether that means being transparent about our failures publicly or creating the conditions for authentic communication within our teams. We have chosen to embrace honesty, and sometimes awkwardness, as the path to an incredible team and a brand worth believing in. It's simple: Don't bullshit yourself and don't bullshit others. LEARN ALWAYS We believe in the potency of a curious perspective and we are obsessed with prototyping. We strive to learn both from failure and success and we believe that teams often forget to value learning as a measurable outcome to any project. We constantly push ourselves to learn new things (personally, professionally, physically, and spiritually). We continually set and test hypotheses that help us to rapidly evolve towards our mission. WE believe that the best way to learn, is to do. MAGIC IS IN THE DETAILS Design matters, the details matter, personality matters, and intentionality is critical. We are tired of hearing that the devil is in the detail. We believe magic is in the details. We have a culture that takes as much pride in a perfectly placed pixel as we do with the design of a page. Overtime, we believe our obsession over detail will speak volumes. WE > I We stand on a belief that the world's greatest challenges will never be solved by one person, one team, or one company. We believe in pathological collaboration and strive to turn competitors into partners. Within our own team and community, we always assume good intentions and when circumstances demand it, we are committed to going through hell or high water for each other. GYSHIDO // VISIT THE SITE We look for a team-player mindset with an autonomous work practice. Unreasonable is not a micro- management culture. We operate under the assumption that everyone on the team will Gyshido and we all hold ourselves accountable. We only work with people who never let others wait for their part of the job. We hold a conviction that nothing grand comes easily. We love the grind. YOUR ENERGY > YOUR TIME If you choose to start your workday at noon or at 5 a.m., so long as you Gyshido, the decision is entirely yours. If you want to go on a hike for three hours in the middle of the day, awesome. We will shape your work around your life. That said, we only work with teammates who feel a deep connectedness to their work. Put another way, we seek out individuals who agree that this is not a 9 a.m. — 5 p.m. job…it's more than that. WE ARE ENTREPRENEURS We leverage creativity and the resources at-hand instead of looking elsewhere for the answers. We believe in the importance of maximizing partnerships, realizing the potential of our team, seeing money not as “the answer” but as a tool to be intelligently leveraged, running a skillfully lean operation, and in short, doing as scrappy entrepreneurs do. GLOBAL IDENTITY We strive to ensure that the demographics of our team and the community we support are reflective of the globally diverse world we operate within. This is not a gimmick, this is a strategic imperative. It is self-evident that the most productive breakthroughs and creative solutions arise from bringing together people and partners across geographies, religions, ethnicities, political affiliations, genders, abilities, and creeds. From our board of directors to our teammates, to the entrepreneurs and mentors we support, we aim to ensure our community and our brand is representative of the world we are seeking to impact. NO ASSHOLES Our greatest asset, the global unreasonable community, thrives implicitly on kindness and generosity at its foundation. We seek out team members, partners, investors, entrepreneurs, collaborators and mentors who choose humility over arrogance, assume good intentions amongst one another, and though we will have many differences of belief and perspective, always treat one another with respect. Though we are a community where creative and social misfits seek refuge, assholes will find no home at Unreasonable. There are no exceptions to this rule. FAMILY AND HEALTH FIRST We know it's ironic that this value is last on the list, but there is nothing more important. Your family and health are always prioritized. If you are sick, if someone is getting married, if there is an urgent family need, we will insist you drop everything and take care of your family and your health above all else. Figure 10.2 Unreasonable Group Manifesto Epstein is clear, though, that putting a purpose and values into words is just “Step 1 to creating a culture that can actually scale. Step 1 doesn't matter if they don't show up in space and time.” Having documented values “immediately changed policy across the company because they conflicted with our values,” he told us. One policy that changed was the company's unlimited paid vacation. “So one of our values is that managing your energy is more important than managing your time,” Epstein said by way of example. “I don't know if anyone on our team ever took any time off. It was so intense that people on our team asked if we had to work on Christmas. ‘Well, no,’ I told them, ‘but if we want to get ahead …’” Epstein's voice trailed off as he recounted the story. Even in remembering the conversation, he was struck at the absurdity of an entrepreneurial drive so intense it plowed through major holidays as a sign of commitment to the mission. What he learned from that moment, though, became an important part of Unreasonable Group culture. “It's not about how efficient you are, it's how effective you are. We needed to have policy to reflect that. Unlimited paid vacation seemed like it supported that value, but almost no one was ever taking vacation. If we actually cared about the value, we had to have policy that reflected that. We now have a minimum of two weeks of vacation. We track the time and if someone works too many days in a row, we force people to take time off. We had to fine tune that one.” Epstein told us that his team embraces the “gravitas of the values” and every employee signs the manifesto when they join the company. Far from a static document, Unreasonable Group's manifesto evolves as the company grows. “Our values are never completely written in stone,” Epstein says. “Every two years or so, the team pushes back as our thinking evolves a bit.” The organic nature of the company's values also lends to its authenticity. That maintenance of values, the building of a culture true to values, requires great care. Culture needs to be modeled and celebrated daily. And, as importantly, anti-culture behavior must be called out and sanctioned when it occurs. If the corporate culture says that every input builds a better outcome, then it's important for business leaders to solicit new ideas across work roles. If you have a “don't be a jerk” value statement, as many companies claim, you can't allow bad behavior to go unchecked, even if the perpetrator is your best-performing sales representative. That seems like a tall order for even the bravest of leaders, but Unreasonable Group's Epstein told us that “it's actually not tough, because it is just so clear to me that if you strive to do the right thing for the right reasons, then in the long term everything is going to be better.” And sometimes, doing the right thing is parting ways with people who demonstrably fail to share organizational values. “We have turned down business and let go of people who were exceptionally qualified, but they have this hue of arrogance around them. We have taken mentors and investors out of the community who are revered publicly because of things like harassment. In the end, it strengthened us,” he said, adding that “It's easy to live by your values when everything is great; it's more powerful to live by your values when in the short term you'll be worse off.” What has living these values meant for Unreasonable Group's business success? Ten years in, this relatively small yet ambitious company has built enduring partnerships with some of the world's platinum global brands. They have a four-year runway for current programs. They have worked with 181 emerging companies in 180 countries, helping them raise $3.7 billion to solve the world's toughest problems. They estimate that through their community of entrepreneurs, mentors, investors, and partners, they have positively impacted the lives of more than 350 million people worldwide. That's the power of intentional culture. Not All Cultures Work so Well Consider Airbnb and Uber. Both emerged around the start of the Global Financial Crisis as so-called “sharing economy” companies that offered affordable access over often cost-prohibitive ownership. Both companies offered on-demand and flexible work—gig work, as it has become known. Both raised billions of dollars at sky-high valuations, making their young founders very, very wealthy. They are different, however, in one very important way. Airbnb was culture driven from the start, whereas Uber was not. Airbnb's culture was intentional. Uber's, arguably, was accidental. When Airbnb closed their Series C in 2012, cofounder and CEO Brian Chesky asked investor and board member Peter Thiel for his most important advice. Thiel reportedly told Chesky (in words more colorful than ours) that he had to get the culture right. Chesky wasn't expecting this response from someone who just invested $150 million in the company, but he took that advice to heart. The company not only defined their values, they made them the central driving force of their brand. Airbnb now fully embraces their tagline: “to belong anywhere.” Uber, in contrast, established a culture around what it does, rather than why it does it. Their early slogans were “Your own private driver” and “To make transportation as ubiquitous as running water.” Both are great aspirations, but neither tells you what Uber believes or why it exists. Arguably, Uber would become the winner-take-all startup driven by the now-legendary early CEO Travis Kalanick. His combative, no-holds-barred and arrogant personality fueled a toxic culture where breaking rules was the norm, women were subjected to frat-boy antics, and public criticism was met with caustic response. Airbnb and Uber were two rapid-growth companies that had similar sharing-economy platforms, and both were dramatically shaped by their leadership. “People don't buy what you do, they buy why you do it,” Simon Sinek reminds us. Airbnb's aspirations helped it remain focused, even in the midst of inevitable and very challenging events with hosts and guests. This has given Airbnb the tools to respond to failures swiftly, make appropriate corrections, and preserve its brand. In contrast, Uber's failures with drivers, customers, and employees were dragged into public forums. Polled in the midst of the public airing, nearly one third of Uber's customers said they were less likely to use the service as a result of reported bad behavior.1 Ultimately, the Uber board needed to remove the company's founder and CEO, Kalanick, and launch a public campaign to polish the company's image. In the best of circumstances, a company operating in the new frontier of the platform economy will face public scrutiny and unforeseen challenges as it disrupts ways of working, takes on regulatory policies, and reshapes entire industries. The grow-at-all-costs strategy to succeed in such endeavors requires a clear purpose and a strong culture to achieve escape velocity with an enduring brand and clear promise intact. As Airbnb and Uber drove hard into the market, one had the culture to respond and adapt to challenges. The other did not. “Aspirational values almost always come from, and must be rectified at, the top,” writes Dr. Cameron Sepah, a psychologist and professor at UCSF Medical School.2 “No behavior will persist long term unless it is being perpetuated by either a positive reinforcer (providing a reward, such as a promotion or praise) or a negative reinforcer (removing a punishment, such as a probationary period or undesirable tasks). Thus, when companies start, leaders set the company's values not by what they write on the walls, but by how they actually act.” The very best organizations—those with the strongest culture and greatest capacity to pursue new opportunity—operate with values and performance aligned, recognized, and rewarded. By this point, we hope you are embracing culture as the structure in which to manage change. By nurturing culture with care and intension, you create the conditions that strengthen your adaptation advantage. Throughout the book, we've preached that the future of work is lifelong learning and adaptation. For you, individually, that means taking responsibility and initiative for learning. You'll be able to power through the continuous cycles of change and adaptation by connecting to your own motivational driver, the power source that is your sense of purpose. As a leader, you can tap into that purpose and inspire your team to a collective mission when you make culture the foundation of your operating principles. But culture alone is not enough for effective adaptation. To get there, you must also nurture culture's partner, capacity. This is where you need to connect the two concepts for effective leadership. If culture is the heart of a company, capacity is its brain. Simply put, capacity is an organization's ability to respond to opportunity. But it is much more than the available space, time, and talent needed to address a new opportunity. Capacity is how we think about new information and ideas in order to assess and respond to opportunity. In other words, it's not enough to ask whether you have the people—or even the right people. You also need to ask whether your people have the mindset to think about this opportunity in the right way. Autodesk's Randy Swearer and Mickey McManus talk about this type of capacity in terms of bias. To be clear, we're not talking about the bias—unconscious or implicit—that pigeonholes people into stereotypes. Rather, bias can be a useful tool in thinking. “Humans have to be biased, because the world is a complex place,” Swearer told us recently. “Frankly, our brains are not all that powerful. Biases are a way that we simplify the world and make sense of it but being aware of them is tremendously important.” McManus makes the point even more clearly with a familiar analogy. “If you have a piece of fabric, like corduroy, it's biased in one direction. You can slide your hand right down the corduroy in one way, but if you slide it 90 degrees, it's really rough and harder to slide. Bias is just a word used for basically creating a shortcut. It requires less energy,” he told us. For us to channel and leverage biases, however, we need to become mindful of them. “We're very interested in thinking about ways to make people aware of those biases and understand the biases that they use to kind of see the world in the sense of making things, but also beyond making things, because it's so crucial today just to exist and to thrive in an environment,” Swearer says. “We feel like the tool itself needs to be, or I should say, the platform itself needs to be a learning platform that is giving people feedback constantly on the biases, even nudging them aware from their implicit biases.” When we apply this concept to technology, we see that technology, which we once needed to learn to use in order to simply work, now becomes something that we learn with and that we learn from and that, in fact, even learns from us. That's the power of digital transformation when tools and humans learn together. Nudging people to be aware of their biases, as Swearer puts it, is all about context. Too often, we treat our companies as if they exist without context until something changes in the business environment that upends all our assumptions—our biases. It might be a change in the technology that breaks the business model, a change in the market conditions that shifts customer expectations, or a change in public policy that adds friction to the supply chain, for example. When these changes of context occur, it is helpful to step back and look at the relationships between the company and its environment, the worker and their team, the human and the technology tool. McManus introduced us to the world of Herbert Simon, an American economist and cognitive psychologist who won the Nobel Prize for his concept of bounded rationality, essentially the idea that humans don't act as perfectly optimizing economic decision makers. Instead, the effectiveness of our decision making must be understood in context. Simon depicted his idea using scissors as a metaphor. One blade is our environment and the other is our capability to respond, what Simon referred to as our “cognitive limitations.” “It's not like you can look at one blade and understand a pair of scissors,” McManus explains. “The interesting action of a pair of scissors is where the blades push against each other. One blade is the brain running these rules. It's got a limited amount of cognition … but it's pushing against this other blade that is the environment.” To lighten our cognitive load, we rely on assumptions—biases—about the environment in which we're doing our thinking. “These biases are kind of shaped by the environment we're in, so we can actually help you see the thinking about your thinking,” McManus concludes. If we keep this interplay in mind, particularly as we experience a whirlwind of change, the necessity of nurturing culture and expanding capacity becomes self-evident. Doing so in harmony becomes essential. Our role as organizational leaders, then, is to expand both human and machine capabilities and collaboration, while celebrating and protecting the organizational culture to optimize environmental conditions—at least internally. In an age when change came slowly and products and brands had long market lifecycles, an executive might be forgiven for conflating culture with brand and capacity with production. It's a mistake that brings a near-sighted focus to the business that often misses shifting context. Consider a classic example. Kodak was really good at silver-halide chemistry, which worked well for decades before digital transformation disrupted the photography industry. Unfortunately, the company had neither the capacity to reimagine how they defined themselves as a business nor the culture to pivot, which is ironic considering that Kodak invented the digital camera. Kodak invented and owned the intellectual property for the very invention that sank a $28 billion business. If Kodak had embraced the purpose in its “Kodak moments” motto and imagined a business beyond (and significantly bigger than) film and print imaging, the company might have endured. Instead the company that invented the digital camera in 1976 reached its pinnacle in 1996 with a $28 billion valuation and 140,000 employees, only to file for bankruptcy 16 years later in 2012. Kodak, of course, is not alone; dozens of companies, for lack of a culture-capacity dynamic, withered in the face of digital transformation. Barnes & Noble struggles to compete with Amazon. Apple's iTunes sank the record business. Perhaps most famously Blockbuster fell to Netflix, the former plummeting from $6 billion annual revenue to bankruptcy in six short years. Countless retail outlets are failing in Amazon's wake, yet a few—like Target, Walmart, and Kohl's—are running innovative experiments to blend online and in-store shopping and, in the case of Kohl's, a partnership with Amazon for a competitive—dare we say it: adaptation—advantage. It's anyone's guess where those businesses will come out, but it's refreshing to see large organizations leveraging their capacity to evolve. It is important to understand the distinction between capacity and capability. A focus on capability, rather than capacity, ties a company's success to a workforce hired to execute the specific tasks to produce a specific product. As change accelerates and product life cycles shorten, capabilities-focused businesses will find themselves stuck in the Sisyphean task of firing and hiring for new capabilities to meet the changing market context. This “spill and fill” model of corporate capability sets companies on an unending chase for talent when they could otherwise be catching opportunity. Worse, it's incredibly disruptive to the workforce and business continuity across three measures: loss of morale and employee engagement among those who remain in the organization, loss of business momentum as new talent is onboarded and existing employees shift roles, and loss of the tacit knowledge often essential to business continuity as employees leave the company. Tacit knowledge is exemplified by—and embedded in—the rituals of how companies work. It is where the “why” of work informs the “how.” It's the stuff you don't know if you don't work in an organization and it's the stuff that is so embedded in daily work habits that you would be forgiven if you forget to mention it to a new employee. Because tacit knowledge is the unwritten history and habits of a company, it is often impossible to regain once lost. Whether tacit or explicit, knowledge is nearly impossible to codify and transfer fast enough to stay ahead of the waves of change. Instead, we can build capacity to learn and adapt by making on-demand learning an integral part of organizational culture. How, then, do strong leaders leverage culture and capacity to drive agile and adaptive learning companies? Curiously, in a scalable learning world, the assets of an organization are measured not in what is produced, but by what an organization can learn. Randy Swearer at Autodesk sums up that idea nicely: You've got these brains that are created at these companies. Those intelligences change over time, but fundamentally, that's all you have. Autodesk doesn't own any buildings. Autodesk owns very little. We lease everything. We're a 10,000-person company, but we lease everything. What Autodesk has is some computers and furniture. It probably rents a lot of the furniture, but basically what it has is talent.” Shift Culture to Expand Capacity We recently spoke with a senior executive who was hired to turn around a traditional, analog company that was struggling with digital transformation. The company's revenue had declined 35% over the prior three fiscal years. Products were missing, and ship dates and technology was failing. As she assessed her team, she discovered a culture of certainty where answers, even if inaccurate, were accepted if they were offered with surety. These familiar statements, perhaps initially reassuring to management, masked big problems. Yet the culture did not afford employees the luxury of reporting problems or asking for help. If a worker's capabilities were not up for the task, she risked losing her job. In order to transform the company and create capacity, the executive needed first to change the culture, and that started with her. If she tried to manage her team's impression of her—masking her own gaps to avoid appearing incompetent—she would be giving her team permission to do the same. Instead, she needed to create an environment of psychological safety to make the space for her team to raise their hands when they need help. This executive now seeks difficult and sometimes painful answers earlier in the process of transformational projects and pairs resources and support with struggling workers in order to expand the collective capacity of her organization. This culture shift requires trust in leadership. If seeking truthful answers becomes a process to identify poor performers, the cultural transformation will fail, and the company will be trapped seeking talent for short-term fixes rather than freed to build long-term capacity. In other words, real leaders show vulnerability and model the culture to empower and strengthen their teams. While we may find it impossible to predict the talent and new skills we'll require in the future, one thing is sure: our old models of expecting skills to be taught in educational programs so that companies can hire for capabilities no longer works. Instead, we need to focus on developing the capacity to learn and adapt while we work, rather than on the capabilities our workforce brings to the job. Capacity-focused leaders build capabilities-retooling into their workforce, hiring people for their learning agility and workplace adaptability in constant cycles of reskilling and upskilling. We're not naming names here, but we're willing to bet this company's story sounds a lot like a company you know. Indeed, the reality is that most companies face this challenging problem. Products Are a Souvenir of Culture and Evidence of Your Capacity The products or services you sell today are likely built with the evidenced capabilities you hired yesterday. What is your plan to create products and services levering the capabilities you don't yet even know you need? You can begin to answer that question by asking several others: Where will you find newly identified capabilities if they are not yet part of an academic or workforce-training curriculum? How do you articulate and socialize your culture? How do you reinforce culture by celebrating cultural wins and calling out cultural missteps? Do you screen new talent for cultural fit? Do you have a hiring plan that focuses on learning agility and capacity for change rather than specific capabilities and past experience? Do you have a learning plan that enables your organization to retool for new opportunities and continually build your capacity? The answers to these questions are the beginning of your own turnaround story. We encourage you to create a plan based on the answers to these questions; it will be the basis of your adaptation advantage strategy. Transforming any organization is a daunting, and often risky, endeavor. But it's possible. Many companies are putting the building blocks of scalable learning in place as they make their digital transformations, often without even realizing it. Whether it's the product or service you create or the methods and means used to market it, every digital interaction is a learning opportunity. Few are doing this hard work as clearly as industry analyst Jeremiah Owyang, founding partner at Kaleido Insights. Owyang's consultancy works with Fortune 100 companies to navigate the challenging waters of digital transformation, creating and implementing strategy to make the crossing from the Third to the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Owyang identified seven components of the Digital Directive—modules, he calls them—that measure the maturity of a company's digital transformation. Each of the seven modules—strategy, data, customer experience, organizational alignment, analytics and AI, people and culture, and innovation—measures a series of specific attributes across all departments to arrive at a deep understanding of the company's ability to cross the digital divide.3 “Many companies talk about ‘digital transformation,’” Owyang writes on Kaleido Insights’ blog, “but use it in a limited fashion, such as just turning paper into PDFs or using web tools to communicate to customers, but in the end, the core culture, and even the business model, has changed.” The Digital Directive is a deep dive that provides a thorough diagnosis of the organization's progress toward—and roadblocks to—true digital transformation. Not surprisingly, Owyang writes, “The most commonly overlooked item is the mindset of workers, managers, and leaders to be a ‘digital-first’ culture.” What's a digital-first culture? Owyang's answer echoes our own. It's a culture that is “making decisions based on data analysis, understanding how to harness information and data as a product, not just physical assets, rapid iteration, acceptance of failure as a means for progress, and developing a culture that is pliable and nimble.” Most importantly, it is a culture that depends on shared values. “Teams have to be empowered to make decisions based on common vision and common values because in a digital-first company you are making real decisions in real time based on real time data,” Owyang told us. “A hierarchal culture won't work. You need to have the culture that works in real time.” In some cases, the learning through data is obvious. In others, not so much. When you take a ride with Uber, for example, you are contributing to their mapping of human movement and their learning about traffic patterns and demands. When you use a Roomba robotic vacuum cleaner, you are helping the company create floor maps of homes to better inform smart home design and create better products. When you click on a sponsored story on Facebook, you are refining the algorithm that targets ads to you. When you engage in news stories on curated sites like Apple News and Flipboard, you are refining the type of content pushed to you in the future. When you ask Amazon's Alexa a question, you are building your customer profile for the sale of future products and services. When you drive a Tesla car, you are contributing to their fleet's learning network that seeks to improve future autonomous driving. And on and on. In each of these cases, the “product” is a means to better understanding of the customer, the market, and future opportunities. The data becomes the basis of learning, which leads to new insights, which leads to new value creation through new products, and the cycle begins again (Figure 10.3). Figure 10.3 Value Created Becomes the By-Product of Increasing Capacity Data provides transparency in creating information about things we previously could not see or measure—new patterns and insights emerge. As our friend and New York Times columnist Tom Friedman puts it, data allows us to digitize, sensorize, automatize, customize, prophesize, localize, optimize, and, we would add, visualize things we could not comprehend before. More succinctly, data allows us to learn. The key to staying on top of corporate lists, then, is learning and adapting. And keep in mind that there is a clear distinction between flexibility and adaptability. Arizona State University organizational behavior professor Jeff LePine puts it best: “Flexibility is the ability to pivot from one tool in your toolbox to another or from one approach to another. Adaptability may require you to drop that tool and forge a new one or drop that method, unlearn it, and develop an entirely new one.” Every company has the unique opportunity to learn from the market experience and the data afforded by their digital offerings. Every user interaction becomes a data point from which to learn. Indeed, the products themselves may be only Trojan horses to collect data from which they can learn. Consider the Hierarchy Ladder of Business Intelligence, where the more you move up and to the right, the greater the value (Figure 10.4). Insights extracted from data are sufficient and necessary to improve products and services. To create new value by offering new products and services, those data-derived insights must couple with intelligence and wisdom—in other words, culture and capacity. Figure 10.4 Hierarchy of Business Intelligence

What Should We Measure?

The Power of the Culture and Capacity Focus

Culture at the Core

Start with Why, the Foundation of Culture

To Build a Thriving Culture, Celebrate—and Sanction—Behavior

Capacity: Culture's Partner

Capability and Context: The Scissors Metaphor

In Accelerated Change, Focus on the Inputs Rather Than the Outputs

Becoming a Learning Company

Notes