2

The Only Things Moving Faster Than Technology Are Cultural and Social Norms

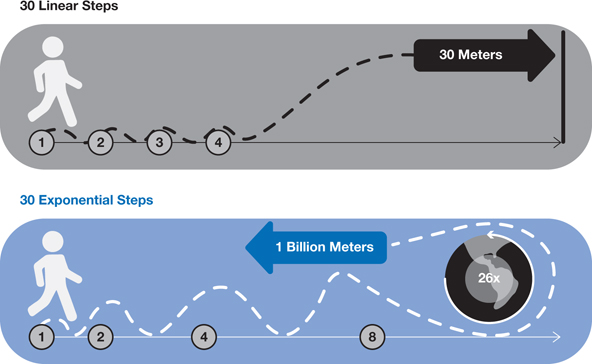

Key Ideas The exponential growth in technological capability explains much about the changes we experience at work, but it hardly accounts for the profound changes we're seeing today in so many aspects of everyday life, changes that inevitably also affect the workplace. Despite, or perhaps because of, the networks that bind us together, societies seem more divided. A smoldering discontent is easily fanned into outrage and anger. Even as empirical evidence shows trendlines that indicate a healthier, wealthier, even happier world population, many people believe the opposite to be true. But why? The simple answer is identity. Our identity is formed and reinforced at an early age. We identify with family, place, culture, ethnicity, and, perhaps above all, work. Consider the questions we commonly ask in conversations. We ask children, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” College applicants are asked, “What is your major?” before even setting foot on campus. And who hasn't broken social ice by asking someone, “What do you do?” That may well make for easy social conversation, but the danger of tying our personal and professional identities together is significant. How can a child imagine a future self in a world changing so fast that many jobs of the future don't yet exist? As the lifespan of many skills grows increasingly short, how wise is it to pursue a tightly defined curriculum when neither life experience nor future visibility provides any real signpost for moving forward? How can we reasonably ask young people to focus on a future self when, according to research by the Foundation for Young Australians, they will likely have 17 jobs across five different industries in their now much longer career arc?1 And when we ask an adult, “What do you do?” we are asking that person to further embrace a professional identity. What, then, happens when that identity is threatened? These questions, it turns out, are traps. They stand in the way of learning and adapting as work environments and opportunities shift and change (Figure 2.1). Instead, we should focus on learning and agility, heeding the guidance of IBM CEO Ginni Rometty, who suggests, “an average skill, particularly in technology, has got a half-life of three to five years. So, what do you do? You actually won't hire for skills anymore, you will hire for propensity to learn.”2 In other words, you will hire for the adaptation advantage. Figure 2.1 Outdated Questions Set Traps Data sources: Frey-Osborne Model, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and the Foundation for Young Australians. Figure 2.2 The Difference Between Linear and Exponential Progress Data source: Singularity Hub. Anchoring identity in occupation will become increasingly dangerous to be sure. Still, we need to put the future of work and work identity in a large context. The truth is that many other aspects of our identity are becoming unmoored as well. What's happening? The answer is that the only thing moving faster than technology is culture. Rapid shifts in social norms are tearing at our individual and social identities, leaving many of us struggling to answer the three basic and oft-asked questions that establish our identity and orient us in the world:

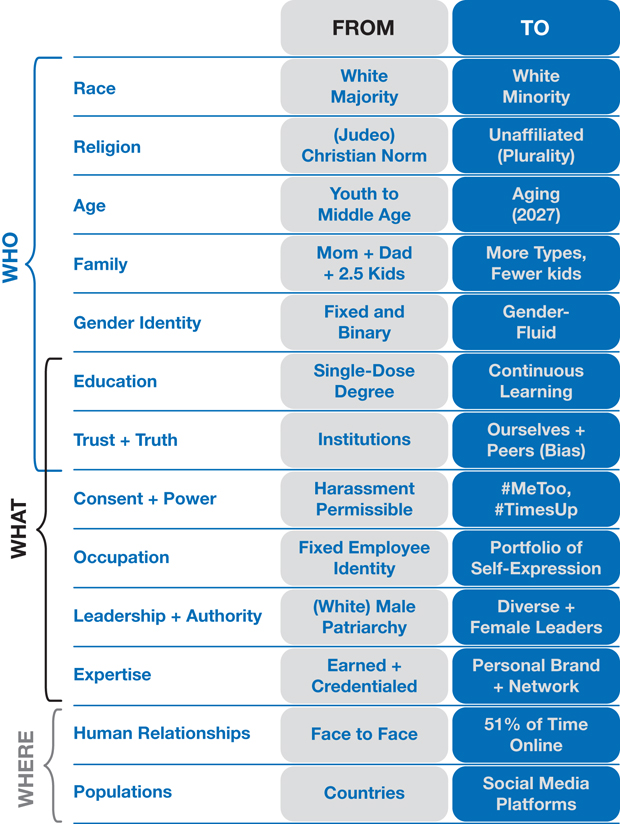

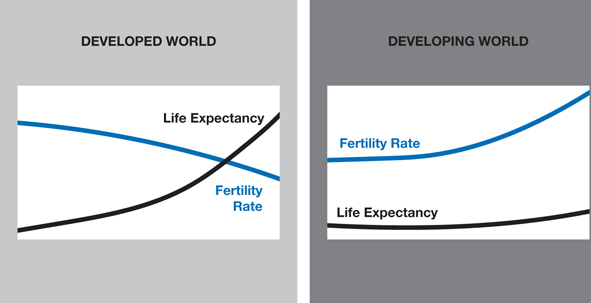

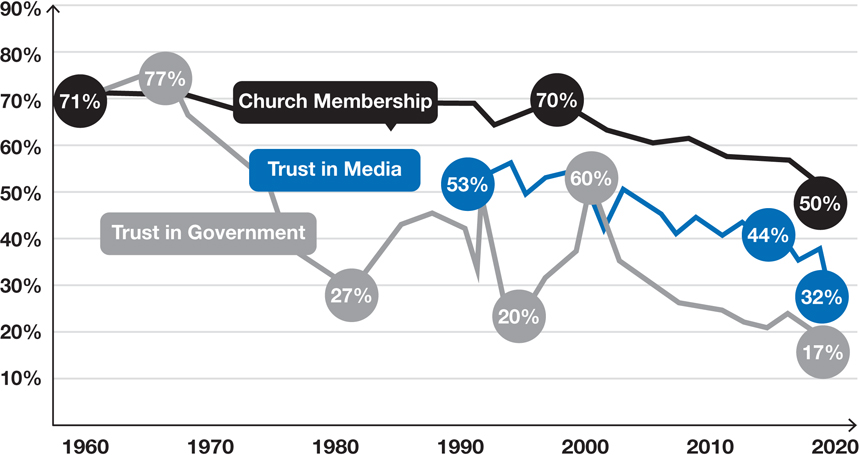

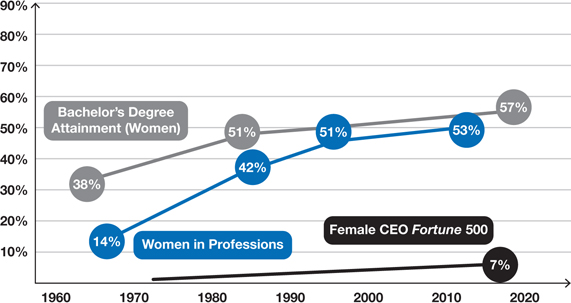

Answering those questions isn't quite as simple as it once was when we lived in a world in which change was nominal and influence and impact were local. Adapting to shifting norms was relatively easy when change was linear, a series of sequential steps—1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Now, driven by accelerated growth and adoption of technology, change has taken an exponential pace, each step increasing the magnitude of the prior one—1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and so on. At an exponential pace, the first few steps feel comfortably manageable, but the further along the scale, the divergence explodes. You may be adjusting now but buckle up; the slowest rate of change you will feel for the rest of your life is right now! Not all that long ago in human history, we only really knew what we could see and experience in a day's walk. New ideas about everything from fashion to religion to politics once took years, if not decades, to migrate from one region to another. Now, ideas move at the speed of light in our hyperconnected and interdependent world. What happens on the other side of the world impacts our economy, our stories, and even our jobs. Let's dive a little deeper into some of these differences (Figure 2.3). Figure 2.3 Dimensions of Societal and Cultural Change Within our lifetimes, the United States and many other developed countries will see their white majority evaporate. In fact, recent census data project that by 2045, white/Caucasian may no longer be the majority race in the United States.3 It wasn't that long ago that a large family was beneficial, especially for families who made their living in farming and other labor-intensive small enterprises. The advent of birth control and planning, coupled with agricultural automation, urban migration, and the skyrocketing expense of raising children brought a marked decline in the average household size. Today, a decline in fertility rates, coupled with immigration from non-European countries, is radically changing the racial composition in the United States and other developed countries. And there's no reason to believe that these shifts won't become even more dramatic as people migrate by choice to escape unstable governments, seek better economic opportunity, or flee areas whose changing climate has made them less suitable for human sustenance. Those whose identity is strongly tethered to a homogeneous racial or ethnic community are seeing that identity becoming unmoored. The United States was founded on the idea of religious freedom, yet we have long been a country dominated by Judeo-Christian norms. So-called “blue laws” dictated business practices on Sundays. Religion was injected into our national language (“One Nation Under God” and “In God We Trust”) and our community practices (prayer before civic meetings and at the start of the school day, for example). That foundation is shifting. The United States is rapidly becoming marked by both a plurality of religions and an absence of religious affiliation at all. In the United States between 2009 and 2019, according to Pew Research, the share of adults who identify as Christian declined from 77% to 65%, while the share who claimed no religion at all rose from 17% to 26%.4 In 2019, Harvard graduated the first class with more declared atheists than declared Christians, the most since its founding in 1636.5 According to research by Pew, Christianity will cease to be the world's largest religion in the next 50 years or so. Islam is expected to grow twice as quickly as the world's population from 2015 to 2060, and Muslims will outnumber Christians in the second half of this century.6 For many whose identity is centered on a particular faith, that pillar may be shaken as that faith is less and less a shared experience among all the peers they interact with. Our once youthful society is aging. In only a few generations, we've seen life expectancy grow from about 40 years in 1850 to 69 years in 1950 and likely 100 years or for those born in 2050. And even as the United States experienced a recent dip in longevity, due in large measure to obesity, addiction, suicide, and homicide, the overall trend toward increased longevity is expected to continue. This extension of life, coupled with declining birth rates, reshuffles age demographics and dramatically disrupts our social and economic constructs. In the United States and elsewhere, for example, our social safety net was built for a lifespan of less than 70 years, assuming a worker would retire at 62 and die by the age of 68 (Figure 2.4.). Now, according to the United States Department of Labor, 4.4% of those over 85 years old were engaged in the workforce in 2018, up from 2.6% in 2006, while workers 30 years old and younger are staying out of the labor force at rates we have not seen since the 1960s, before women joined the labor force in masse. This shift in retirement age is evident no more clearly than in the American Association for Retired Persons, or AARP. One of the world's largest nonprofit membership organizations with 38 million members, AARP kept its acronym and changed its name to the American Association for Real Possibilities to signal the shift from retirement to later-in-life encore careers. In 2019, AARP joined forces with the World Economic Forum and OECD in a global initiative called Living, Earning, and Learning Longer to encourage employers to rethink their relationships with older workers, a topic already on the agenda of the 2021 World Economic Forum in Davos. These leading organizations are signaling a profound shift in how we think about people in our society whom we have long considered “retirement age.” Figure 2.4 Shifting Population and Aging Trends Worldwide Data sources: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Population Prospects 2012, Bureau of Labor Statistics, World Bank. In the United States, we build and market products and services for the coveted 18- to 44-year-old age group, even as demographers predict that by 2027, just a few years from now, more people will be over the age of 65 than under the age of 14. According to the US Census Bureau, the number of adults over 65 is on track to double between 2000 and 2030; those over 85 are the fastest-growing segment of the US population. In Asia, and particularly Japan, where more than 12% of the population is over 75, these shifting demographics are having a profound impact. Will there be an adequate labor force to sustain the economy and enough caregivers to tend to the elderly? In parts of the developing world, advances in and access to medical care have reduced the infant mortality rate but have not as dramatically increased overall life expectancy. The lack of readily accessible birth control, the desirability of large families for providing agricultural labor, and the relative lower cost of raising children is driving overall fertility rates considerably higher than in developed countries. So while the developed world is adapting to aging societies, youth booms in the developing world demand a different adaptation. In the Middle East and Northern Africa, 66% of the population is under 25. In Egypt, 50% of the workforce is under 30. We can expect these trends to continue, and while developed and developing worlds may have to adapt differently, it is now imperative to rethink work, retirement, and how we structure all aspects of our societies from city planning to social safety nets, and even products and services designed to accommodate dynamic age redistribution. And we need to start rethinking now. The baby born today with a life expectancy of 100 years or more will grow into new and adapting social structures. More urgently in need of a reimagined future is the 55-year-old woman who launched her career some 30 years ago, planned to retire at age 65, and expected to live into her 70s. It's quite reasonable to assume that she will outlive that expectation by a decade or more. For her, and likely most anyone born in the United States after 1965, we need to pool our collective strength and imagination to jettison our increasingly old-fashioned idea of work and retirement and begin to plot a new future that weaves the strands of learning, work, and “retirement” through a long and productive life. For much of the twentieth century, the word “family” evoked images of Mom, Dad, 2.5 kids, and maybe a dog. Today, that view is not so easily conjured. Declining fertility rates in the developed world7 have all but made extinct the middle child. In 2016, 40% of children in the United States were born outside the institution of marriage, up from 28% in 1990.8 The once “nuclear” family is giving way to extended families, as grandparents, aunts, and uncles engage in primary caregiving for children and aging adults. Children living with only one parent account for 27% of families. Some 6 million Americans are children of LGBTQ-identified parents, and the rise of marriage equality globally is spawning families of choice rather than biology. These reconfigurations of family challenge the boundaries of traditional values when those values are exercised in unfamiliar ways. Gender identity was long fixed and binary. Check a box: Are you male or female? Not so anymore. Gender identity is changing perhaps faster than any other social construct. In a word, gender is now fluid. In various business, academic, government, and other forms, you may be asked to declare your personal pronoun preference. After your name in your email signature line, you may simply offer: She/Her/Hers or He/His or They/Theirs. By the end of 2019, 14 states in the United States offered “X” in addition to “M” and “F” as options in answer to gender questions, up from only three states the previous year. People of Latin American dissent once referred to themselves as Latino (male) or Latina (female), and now more frequently use Latinx to signify liberty from a gender marker. Take the London Underground public transit today, and you will be greeted with “Good Day, Everyone” where “Ladies and Gentlemen” were welcomed until mid-2017. “We have reviewed the language that we use in announcements and elsewhere and will make sure that it is fully inclusive, reflecting the great diversity of London,” said London mayor Sadiq Khan at the time. In Fall 2019, both Merriam-Webster and the Oxford Dictionary added “they” as a third-person singular pronoun for nongender binary individuals. A few months later, Merriam-Webster selected “they” as the word of the year for 2019. The shift from fixed to fluid gender identity is being fueled by younger generations, Pew Research discovered. By the end of 2019, 35% of Generation Zers and 25% of Millennials reported knowing someone who uses gender-neutral pronouns. Compare that to 16% of Generation X, 12% of Boomers, and 7% of the Silent Generation who report the same.9 Gender identity is core to both personal identity and our ability to relate to and connect with others. What was once largely “obvious” is now cautiously questioned, changing one more touchstone in the identity framework. From the advent of radio and then television, a handful of networks and media delivered the daily news, mostly objectively, thanks in large part to the Fairness Doctrine that required broadcasters to give equal time to opposing views in order to secure their broadcast license. When CBS newsman Walter Cronkite signed off his broadcasts with the signature line “And that's the way it is,” his viewers believed him. In fact, in a 1972 poll, Cronkite was named the most trusted man in America. Fifteen years later, the much-debated Fairness Doctrine was no more, repealed by the FCC. New networks with obvious political opinions on both sides of the aisle made the scene, and before long, “fact” and “analysis” swam in the same pool. You could find a “truth” that best fit your personal ideology simply by changing channels. An unregulated Internet—no broadcast license required—proved fertile ground for ideologies out of the mainstream, giving voice to fringe ideas and further blurring the line between fact and fiction. With social media's ability to amplify and target information, true or otherwise, it's no wonder that trust in media has withered. Over the past decade, according to a survey conducted by Gallup for the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation's Trust, Media and Democracy initiative, 69% of Americans say they have lost trust in the media. Not surprisingly, respondents trusted media in varying degrees according to their personal political leanings, further entrenching themselves in political tribalism. The proliferation of news sources and the inclination to cherry-pick facts and reject uncomfortable “truths” has eroded a once-common American experience: the day's news delivered by a trusted news anchor. It's just one more way our common identity has frayed. At the same time we're witnessing a decline in trust in both government and media, we're seeing a rapid decline in church membership. Losing faith in our fundamental social structures signals a crisis in belonging, one that underpins a loneliness epidemic (Figure 2.5). In 2019, the health insurer Cigna surveyed 20,000 Americans and found that nearly 47% reported feeling alone or left out. This phenomenon is not unique to the United States. More than 40% of Britons reported that their primary sense of company is a pet, leading the UK to create a government-level position to combat loneliness. A government study in Japan found that more than a half a million people had gone at least six months at home without human contact.10 Figure 2.5 Membership and Trust Data sources: Gallup (church membership and trust in media), Pew Research (trust in government). Women entered the workforce en masse in the 1970s and now, almost 50 years later, we are seeing the dramatic (if slowly attained) shift in how women and men are treated at work. Women are earning increasing respect, power, and authority in the workplace, academia, and all walks of life (Figure 2.6.). Figure 2.6 Women and Work: Educational Attainment, Workforce Representation, and Leadership Data sources: Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (women in professions), National Center for Education Statistics (degree attainment by women), Catalyst (Fortune 500 CEOs). Far from the power dynamic of the Mad Men era, women score higher than men on a vast majority of leadership competencies, according to research published by Harvard Business Review.11 (The same study noted that we have much more work to do to bridge the advanced degree and leadership gap for underrepresented minorities.) Women now far outnumber men among recent college graduates in most industrialized countries.12 Indeed, women have outnumbered men in degree attainment in the United States for the past 20 years. In 2015/2016, women earned 61% of associate's degrees, 57% of bachelor's degrees, 59% of master's degrees, and 53% of doctorates.13 In 2019, university-educated women, for the first time, outnumbered university-educated men in the workforce in the United States.14 Despite this pipeline of talent, and with a workforce that is 47% women as of 2019, only 5.4% of the CEOs of S&P 500 companies15 and 7% of Fortune 500 CEOs16 are women. If you consider venture-backed startups a pipeline to leadership of quickly scaling businesses, the numbers are not yet there for women, either. In 2017, just 2% of venture capital funding went to startups founded by women, and women made up just 9% of the decision-makers at US venture capital firms.17 Still, we are seeing change. The 2018 midterm elections in the United States were marked by the greatest number of women and the most racially and culturally diverse candidates in history. Ninety women were elected to Congress, including, at age 29, the youngest woman ever elected, along with the first transgender representative, the first openly bisexual representative, the first Native American representatives, and the first Muslim representatives. The US representation in government is coming closer to mirroring the populace it represents. In corporations, gender equality may come more slowly but will accelerate as structural and policy changes take effect and the pipeline of talent becomes balanced. California passed a law requiring publicly traded companies headquartered in the state to have at least one female board member by the end of 2019. Moreover, the “Me Too” and “Time's Up” movements catalyzed an important dialogue about gender-based power dynamics. There still may be a far distance to travel, but we are taking solid steps toward equality. Yet we must also acknowledge that the shift in the gender-based power dynamic in education, business, Congress, and beyond both threatens and empowers, and it has certainly left many men feeling adrift. Anne Case and Angus Deaton famously coined the term “deaths of despair” to capture the decline in life expectancy for largely non-college-educated, non-Hispanic white men who have been unable to participate in the modern economy, a demographic that has experienced a dramatic rise in deaths from opioids, alcohol abuse, suicide, homicide, and other mental health–related deaths.18 This sad trend is one of the most challenging aspects of adaptation to the new economy. If you are not well prepared to participate in a changing labor market, and if your social status is being reshaped by changing demographic and gender norms, how can you be comfortable in the vulnerability required to learn and adapt? Human populations have always aggregated in physical communities, city-states, and countries. Now, though, these geolocated populations are being eclipsed by a new form of association—online platforms. As we discussed in Chapter 1, the top 10 population “centers” in the world include only two countries. The other eight are social media platforms. With little friction to slow digital flows, this change occurred in the past five years. Since societies are formed by a common language, culture, currency, and assets, we have to consider how new societies will be enabled by digital technology. Language can now be translated in real time by artificial intelligence. Cultures are forming and clustering in social media rather than IRL (the text messaging acronym for “in real life”). Currencies, once backed only by governments, are forming around a collective agreement of value exchange, and assets once backed by the gold standard are now understood as digital goods captured in intellectual property, algorithms, and artificial intelligence. By some estimates, people in the developed world are spending 51% of their time online. Check your mobile device to see how many of your waking hours you spend on screen time on any given day. If your time looks like most people's, you are spending more than half your time in a “place” other than where we are physically located and engaging with people we may have never met in person. Yet, paradoxically, even as we are more connected, we are lonelier. In fact, according to the previously mentioned Cigna study, the most digitally connected generation, Generation Z, is also the loneliest. This epidemic of loneliness has serious consequences, impacting health and mortality to a degree equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day.19 This formation of new, virtual societies reinforces the information and relationship filters that fortify our biases and beliefs. Our time online has changed how we socialize, shop, find jobs, and even find mates. Twenty-one percent of heterosexual couples and 70% of same-sex couples now say they met their partners online (Figure 2.7). These are some seriously solid filter bubbles. Figure 2.7 How We Meet Our Mates Data source: Michael J. Rosenfeld and Reuben J. Thomas, “Searching for a Mate: The Rise of the Internet as a Social Intermediary,” American Sociological Review 77, no. 4 (2012): 523–547. If so many facets of identity are being reshaped, the question “Who are you?” may be more rightly changed to “How do you define yourself?” Psychological security will be dependent on our abilities to define, own, and embrace the fundamental aspects and values of our complex selves, especially in a world where we are not likely surrounded by people who look, eat, pray, or speak like we do. When our gender, family, and racial and cultural clans give way to diverse and global communities, we need to find new tethers for our complex identities. Likewise, that ice-breaker question “What do you do?” loses its relevance when our job is no longer our primary identity. “Where do you find purpose?” may be the better question in a world where your career identity is fluid at best and more likely becoming a portfolio of self-expression. How do you express your professional expertise in a way that is nimble and adaptive? The trick is to root your sense of self to your purpose, passion, and curiosity. Work we love, work with purpose, is essential for every worker, not just the luxury of a few. Curiosity, purpose, and passion fuel lifelong learning and give us our adaptation advantage. But to be clear, purpose is not some inner secret that is magically revealed. Rather it is carefully curated over a lifetime. As Annalie Killian with New York–based management consultancy sparks & honey puts it so well, “Purpose is not found but discovered through the editing process of life, trial and experimentation.” Finally, in this emerging digital era, how we connect and create community will supersede geographic and ancestral identities. The idea of being “from” a place will give way to a sense of belonging. These cultural shifts find a common basis in technology's ability to move information at the speed of light. We see a wider landscape than ever before, and in that context, we begin to see ourselves differently and too often as different from the “other.” As our cultural identity peels away, our instinct often is to retrench, to cling more tightly to what is left of our prior selves. It is our best and worst instinct. We are too confident in who we are to move in the direction of who we might become. As Dan Gilbert reminded us in our introduction, it is easier to remember than imagine. Worse, these culture shifts have too often been politicized, skillfully used by politicians and manipulated through social media to divide our societies. According to Pew Research, the United States, for one, has long been evenly divided among Democratic, Republican, and Independent voters. Now, we are highly polarized between the right and the left, while 43% of the population finds no home at either pole; nowhere is this more true than with Millennials, 50 percent of whom now identify as Independents.20 Politically, socially, or geopolitically, we need to find a way back to belonging. That way relies on a secure sense of identity, being confident enough to admit the vulnerability that enables new ideas and knowledge to take root. Your adaptation advantage starts with a resilient and adaptive identity, even as the forces of globalization, diversity, and changing social and societal norms reshape your touchstones.

Shifting Ground Beneath Our Feet

From Linear and Local to Exponential and Global

Race

Religion

Age

Family

Gender Identity

Truth and Trust

Consent and Power Shifts

Death of Distance Reshapes Human Relationships

So, Who Are You? Occupational Identity and Expertise

Notes