3

You're Already Adapting and Not Even Noticing

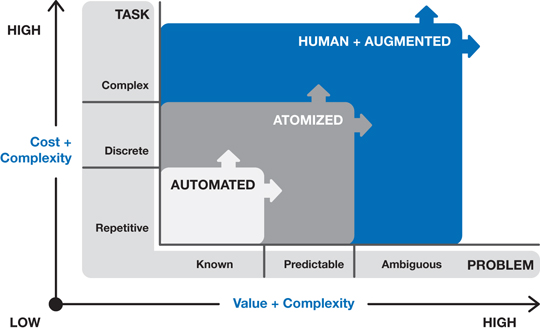

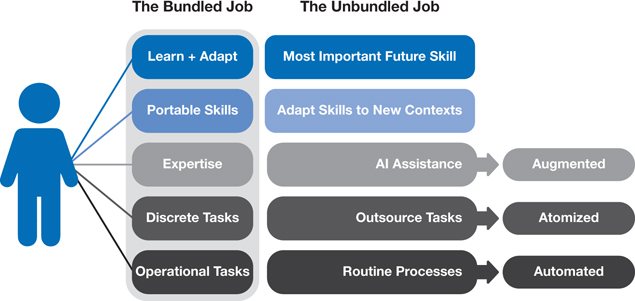

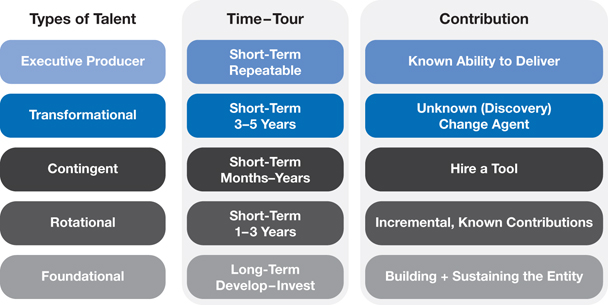

Key Ideas In the early days of 1996, Jeff Hawkins took the stage at the technology industry's DEMO Conference to introduce the PalmPilot to an audience of technophiles eager to see the future of mobile computing technology. This was the first widely adopted personal digital assistant (PDA) and the precursor to the smartphone, which Hawkins and his team at follow-on company Handspring would bring to market six years later. The PalmPilot included a contact list, datebook, calculator, to-do list, and notepad. By today's standards, this was a very simple device, yet it had a profound impact. The day the PalmPilot came to market was the day we began to outsource our memory to digital assistants. In truth, though, this outsourcing began long, long ago. That's the way it is with “technology.” The most rudimentary hand tools extended human potential. The invention of written language meant humans could document their stories to be remembered for generations. Computer technology was all that on steroids. Most prosaically, Steve Jobs called the personal computer a “bicycle for the mind,” a machine profoundly extending human cognitive potential by storing and retrieving information, executing calculations at the speed of light, processing mountains of data in moments, and even orienting us in time and space. Hawkins’ handheld digital assistant was simply one more accelerant in a long train of human augmentation. Think about it: your mobile phone contains dozens, if not hundreds or maybe thousands, of phone numbers. If you lost your phone right now, who could you call? Maybe you remember your own number or the number that rang in your childhood, or maybe that of your partner. Or maybe not. We no longer memorize phone numbers because we don't have to. In fact, we send them from phone to phone without them ever passing through our brains. Our phones contain hundreds of photos and not just of our fabulous selves. We use the camera as a visual notepad to remember everything from what we ate to the parts we need to buy at the hardware store to the space where we parked our cars. Calendar and alarm functions remind us where we need to be and by when, and weather apps tell us what we need to wear when we get there. Calendar appointments synchronize with traffic data to tell us when to leave to arrive on time. Social media platforms like Facebook remind us of past experiences by resurfacing posts, and they never let us forget a friend or loved one's birthday. Our apps count our steps, summon rides, find us a date, order our groceries, and connect us to the biggest brain of all, the Internet. Estimates are that, today, in the developed world, we spend 51% of our time online. That's more than half our waking hours, and for many of us it means we are spending more time nurturing our virtual communities than our physical ones. So much so that we developed a text-message acronym—IRL, in real life—out of the necessity to delineate between real and virtual events. Ironically, few of us find any of these technology-enabled devices very scary, in stark contrast to the ominous warnings that robots and AI are gunning for our jobs, and maybe even our humanity. The fact is that new technologies have always had a way of augmenting human capabilities. Steam engines augmented our ability to move from place to place. Telecommunications augmented our ability to be in conversation with people at a distance. Electricity extended our days beyond the hours of sunlight. Computers augmented our ability to calculate numbers and quickly process standard tasks. The World Wide Web augmented our ability to publish and widely distribute our ideas. And so it goes. Today technology has lowered the cost of labor for most physical tasks, and is now encroaching on high-level, professional cognitive work—law, medicine, and business—that was once thought to be safe from technology disruption. Artificial intelligence technologies coupled with lightning-fast processing and access to massive stores of data are eclipsing human cognitive abilities in narrow areas where tasks are specific and clearly defined. Consider these examples: Betterment is a low-cost robo-advising application that uses artificial intelligence to manage your financial portfolio at a fraction of the cost of a human investment manager. Ross is the first artificial intelligence–based legal research service. Each of these systems performs specific tasks more quickly than humans, but it is humans, ultimately, who make sense of these applications. When we describe the capabilities of a motor today, we talk about “horsepower”—a unit of measurement that compares the power of the machine to the organic assistance it replaces, a throwback to the time when these new engines needed a point of reference to the horses that previously did the job. Technology will continue to advance and assume many routine and predictable tasks at all skill levels. That idea strikes fear in many, but it shouldn't. Humans are far more adaptable than horses. We will do as we have always done in the wake of new “technology”; we will continually reskill, upskill, and reinvent ourselves in order to adapt. The only difference is that we have to adapt faster and more frequently now. And adapt we must. Research by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that “on average, the arrival of one new industrial robot in a local labor market coincides with an employment drop of 5.6 workers.”1 What may be a frightening statistic, though, can also be an important reminder to make upskilling and reskilling an everyday activity. Why wait? By building the muscle to continuously adapt, we minimize the disruption caused by the way technology and globalization are changing work. We need to continuously adapt so disruptive technologies are not, in fact, so disruptive. Three driving forces—atomization, automation, and augmentation—are dramatically reshaping work and will continue to do so for decades to come. By paying close attention to how these forces are reshaping work and our world, we can learn and adapt to maximize their transformative power, rather than fall victims to redundancy (Figure 3.1). Figure 3.1 The Atomization, Automation, and Augmentation of Work Today, the tasks of many jobs—particularly those at an entry level and increasingly those in the more advanced professions—can be broken into separate, discrete pieces. Those pieces, particularly if they are fully digital pieces, can be solved by the best and lowest-cost provider anywhere in the world. This is the atomization of work. We saw the benefits of this type of unbundling of a single piece of work from the job that contained it in the mass manufacturing of products in the Second Industrial Revolution. The atomization of work occurred as “piecework”—components needed for a completed product were made by individuals in various workshops, then shipped to a central manufacturing site for final assembly. In the digital age, as some tasks become certain and their outcomes clearly defined or at least predictable, they will be assigned in whole or in part to computerized labor. This is the automation of work. The robots that supported and often supplanted factory workers in physical labor are moving into the professional ranks and encroaching on knowledge labor. Today, computer algorithms can analyze reams of data far faster than human workers can. Indeed, every job in the developed world is aided by some form of computer technology, from computation to scheduling to scanning to sensors to detecting patterns. IBM's Watson has shown some promising potential in its ability to scan and analyze legal briefs and early efforts to detect patterns in an MRI. This is the augmentation of work. As we wrote this book, we needed to transform our PowerPoint graphics used in keynote talks to the vector graphics more suitable for print. Using the gig work platform Fiverr, we found Olga, a Serbian graphic designer at Josephine and Paul Designs. Olga has, working hours opposite of ours, transformed our graphic frameworks to the high-definition file formats required by our publisher. The work was done to specification efficiently and cost effectively. In this task, Olga was a part of our team. Where in your work can you identify tasks that can be handed to another provider to solve? Tapping into the global talent cloud allows you to find someone to do that work, perhaps even in another time zone, thereby extending your workday. Google is bringing automation to your Gmail inbox. By adjusting a few settings, Google can scan your email for event- and task-specific items, then automatically put the relevant information about an event in your calendar. If you travel as much as we do, you'll appreciate the reduction in time and frustration when you no longer need to search for information because the automation in Gmail has placed hotel addresses, flight confirmation codes, and other relevant information where you can easily find it. It even pops up a reminder when it's time to check in. Google Calendar also integrates with Google Maps and Waze to scan traffic and suggest a departure time so that you are not late to your next meeting due to a traffic delay. Gmail has also begun suggesting quick responses to routine emails, enabling you to dispense with your inbox in a fraction of the time it would take to draft replies on your own. Many routine and narrowly defined tasks like this can be automated today. Where in your work can you find tasks to automate? Upskilling and Reskilling Exercise One way to adapt to technical disruption in your work is to assess your job by scanning the marketplace for opportunities to outsource, upskill, and reskill. Upskilling is deepening your knowledge and skills in your current domain. Reskilling is extending your knowledge and skills to new domains. Consider which tasks can be handed off to atomization or automation, scan for new technologies that may augment your capabilities, and seek new skills and knowledge required to evolve the value you create today to a new business model. Doing so will allow you to adapt, reskill, and upskill ahead of the curve (Figure 3.2). Figure 3.2 Upskill and Reskill Regularly As we began work on this book, Heather was struck with a rare and life-threatening health event: a massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage caused by a very, very rare condition called Dieulafoy's Lesion. Until recently, 80% of patients with this condition died from internal bleeding before the cause could be diagnosed. Advances in both interventional radiology and endoscopic procedures expanded the potential of her surgeon, who, with the help of these technologies, diagnosed and successfully treated her with only minimally invasive surgery. If you work in healthcare, you are surrounded by technological advances and experiments—from the da Vinci robot that extends the precision of a surgeon's hands to experiments with various forms of AI to detect patterns and diagnose conditions—that augment the quality of care delivered by human providers. Outside of healthcare, AI technology is augmenting all sorts of activities, from stock trading to legal work to sports strategy. You might even be driving a bit of AI technology if your vehicle alerts you to something in the blind spot, offers adaptive cruise control, or assists in parking your car. The forces of atomization, automation, and augmentation will continue to transform work and deliver new capabilities until, ultimately, most tightly defined tasks are captured in algorithms that execute jobs faster, more predictably, and more efficiently than any human worker, no matter how low cost or how intelligent. Algorithms augment until they replace many human tasks and skills. This is how atomization and augmentation of work interconnect to accelerate the transformation of work. Once a job has been atomized and the routine and predictable components digitized, the atomic parts of a job can be parceled out to a global workforce willing to complete a task at the lowest cost with the highest quality. These workers are a resource in a human talent cloud in much the same way the software applications or data storage are now relegated to Internet-based systems, often referred to as “the cloud.” In effect, the work to be done has been separated—unbundled—from the job itself, and workers from anywhere in the world can come together in a virtual workplace. This transformation will continue until ultimately every clearly defined, objectively measured task is captured in an algorithm that can replace human work. Experts debate just how quickly these changes will fall into place, but the consensus is clear: work that can be replaced by an algorithm will be. Today's jobs, if they exist at all in the future, will have likely had the atomizable and automatable elements stripped out of them, with only computer-augmented expertise, portable skills, and learning agility remaining. But to be clear, the functions that can be captured in an algorithm are really only the tip of the capabilities iceberg. Many uniquely human attributes contribute to our work. They are fundamental to our ability to create and share value (Figure 3.3). By developing these uniquely human skills, we further build our adaptation advantage. Figure 3.3 The Unbundling of a Job And even while technology is subsuming many job functions, there are many reasons to be optimistic. Aided by automation, we are producing goods and services at lower and lower costs, making even advanced products more affordable to more of the populations around the world. Consider, for example, an Apple iPad. Introduced in 2010 at a price of about $700, a lighter, brighter, more capable version of that iPad costs about $250 today, which is a superior product at 37% of the cost in under a decade. More importantly, rising machine intelligence advances our potential to solve the most complex and threatening problems, from disease to climate change to the efficient use of resources. Working in tandem with technology, people can create, solve, and shape the world for the benefit of all. In fact, we will need advancing machine capabilities to offset population declines in the developed world as our demographics shift dramatically, particularly in the United States. The forces of atomization, automation, and augmentation are not just changing jobs; they are radically changing where and how people work. Companies that have been “containers” for jobs in which work was done will become “platforms” that leverage both technology and human talent to deliver productive outcomes (Figure 3.4). Employment itself will take various forms: foundational (those whose work is primary to the operation of the company), rotational (those whose work is periodically required), contingent (those whose often very specific skills are needed for a specific task), transformational (those brought in to navigate a change in organizational or product strategy), and executive producers (those who bring specific talent and networks to deliver a project or event). In his book The Alliance, founder and chairman of LinkedIn Reid Hoffman writes of people working in “tours of duty,” wherein they cycle through specific projects, finishing one and moving on to the next, sometimes with a bit of respite or reskilling in between. Figure 3.4 Five Types of Talent Concept credit: Reid Hoffman (foundational, rotational, and transformational talent), Heather E. McGowan (contingent and executive producer talent). Coupled with the rise in computerized intelligence, this is a sea change not only in how work is done, but also in what humans do and how they gather the skills to do it. Gone will be the days of a straight-line path through college to work to promotion to career to retirement. (For more on this, please read the book's Introduction.) Instead, we are finding ourselves on a cyclical road where more and more tasks are offloaded to machines while we upskill our capabilities in uniquely human ways. Many people find this prospect exhilarating, but there are as many who find it breathtakingly frightening. But keep in mind that we've been augmenting and adapting to new technologies and new ways of work for hundreds of years. Every time you embrace a new capability of a product or service that you already use or adopt a new product altogether, you've adapted. The difference now is speed. You can do it because you already are doing it. Think back over your lifetime. You have adapted to dozens of things you once found unthinkable. Depending on your age, you have likely adapted the way you bank, for example. A trip to the local bank became a stop at an available ATM, which became an app on your phone. And phones? From hard-wired devices to brick-sized cell phones to robust and versatile smartphones, we've adapted to so many aspects of communications that most of us have forgotten—if we ever knew—the sound of a dial tone. Television has transformed from programmed airwaves to cable to on-demand Internet, and so have our television watching habits. And few of us, we'd bet, would be willing to go back to typewriters and adding machines. Technologies deliver great convenience and advantage, even if they require adaptation. Now, as technologies change the face of work, we will adapt at a quickening pace. Change? Sure. But you've got this. You already have an adaptation advantage. We have been told for decades that we have to “robot-proof” our careers, and that's the folly. There is nothing that can be taught to prevent any of us from having to adapt. The good news is that we are already adapting even if we don't sense it happening. Humans will continue to adapt to take on new roles, the ones that are not clearly defined or objectively measured. In other words, the automation and atomization of work frees human workers to do better and more fulfilling work by outsourcing the dull and routine tasks. The same holds true for cognitively intensive work; human potential is enhanced through augmentation. Artificial intelligence systems such as IBM's Watson are being trained to detect cancer in MRIs and early prototypes show promise in their ability to do so. In a 2019 experiment, Vice News pitted the LawGeex AI against Tunji Williams, a graduate of one of the country's top law schools. The AI analyzed contracts with greater accuracy and greater speed than the human lawyer. But here's the good news: these highly skilled humans can now focus on that which is uniquely human: applying that discovered knowledge and caring for patients and clients. When asked why he wasn't upset by the legal smackdown upset, lawyer Williams told Vice News, “I wasn't disappointed when the iPhone came out and I could do more things with this piece of technology, so this is exciting to me.”2 Williams understood that by embracing his adaptation advantage, he could do more, and even better, work. Even jobs thought to be based in human creativity will benefit from augmentation. Renowned industrial designer Phillipe Starck, for example, created for Italian furniture maker Kartell a production-ready chair designed in collaboration with an artificial intelligence. Working with the computer-aided design company Autodesk, Starck taught the generative design software to understand design requirements—for example, the size, capacity, weight, and cost constraints—and the software offered hundreds of design options in return. Starck told editors at the design magazine Dezeen that the experience was “a lot like having a conversation.”3 Presented with hundreds of viable options, the designer can curate the computer-generated solutions and even 3D print samples using the software's specifications. Cognitive automation is largely invisible because it happens in software. When Gmail interprets an invitation and puts a meeting on your calendar, that's adaptation. When that same application completes your sentences to make responding to and composing email messages quicker, that's adaptation. When you use the self-checkout lane at the supermarket, zip through a toll booth using a dashboard sensor, or ask Alexa to play your favorite song, that's adaptation. These are new, faster, cheaper, more efficient ways of doing things that once required at least some human intervention. Automation will continue to develop gradually and is already happening in things you take for granted or even enjoy. And the fact is, companies have been using automation to redistribute workloads between systems and people. Still, there is plenty of work to do. If automation is the process of redistributing work between systems and people, people need to think about where they want to go once they've been relieved of the mundane tasks. And that's the tricky part. Every time you hand off something to an algorithm, you need to reach for something new. If you are handing your cognitive load to technology-enabled devices and services, what are you reaching up to learn? We are good at the handing off; we need to become better at the learning. And we have to become better at learning quickly and deliberately in order to “repace” evolution. That is the adaptation advantage.

We've Already Begun to Outsource Our Memory

People Aren't Horses

Atomization, Automation, and Augmentation

Atomization in Action

Automation in Action

Augmentation in Action

Putting Atomization, Automation, and Augmentation Together

Notes