5

What Do You Do for a Living? The Question That Traps Us in the Past

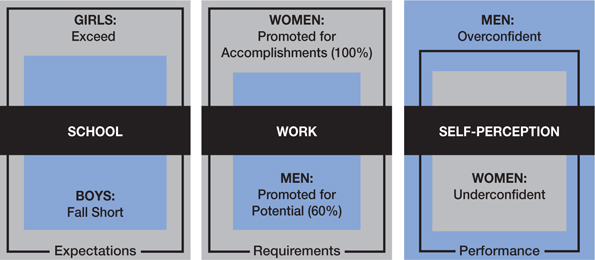

Key Ideas Throughout our lives, we've gotten to know one another by asking three seemingly simple questions: “What do you do?” adults ask one another. “What's your major?” we inquire of university students. And who hasn't asked a child, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” We use these questions to orient ourselves in the world, to describe and define ourselves and one another, and to give our academic pursuits a sense of direction. These questions, though inquisitive and well-meaning, might be just the thing that tethers us to a fixed identity and denies the fluidity that adaptation demands. Rather than giving us direction, purpose, and identity, these questions can become traps hindering personal growth and evolution. In the United States, if not most places, it's the icebreaker at gatherings both professional and social. The answer is layered with social signals. “I am a lawyer,” one person might say, and we imagine the intelligence and diligence required for the paper chase. We probe on the legal focus—corporate litigation, civil rights, malpractice, family law—and recalibrate assumptions. “I am an elementary school teacher,” another person answers, and we envision the patience of the job required to mold young minds. Still another says, “I am an entrepreneur,” and we make our assessment: a future Gates or a wide-eyed dreamer? Doctor. Banker. Architect. Journalist. Account executive. Yoga instructor. Union steward. How we describe ourselves, the context we give our occupational identities, is fundamental to who we know ourselves to be. Take away that easy label and many of us become unmoored. Who are we, if we are not our jobs? In fact, studies have found that the loss of a job—and its associated identity—is more damaging to our emotional well-being and takes a longer recovery time than the loss of a loved one.1 Consider the implications of that finding when nearly 5 million people, voluntarily or not, separate from their jobs each month, according the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Five million people! That's like everyone in the state of South Carolina wondering who they are now that their job is gone. Each and every month. And all signs indicate that this number will grow even bigger in the future. The professional social networking site LinkedIn found that people who graduated from universities in the United States between 1986 and 2000 averaged 1.6 jobs in the five years after graduation. That number jumped to an average of 2.85 for those who graduated between 2006 and 2010.2 The phenomenon is applicable to all developed countries. That data is reinforced by the Foundation for Young Australians, which projects that young people across the developed world and graduating from college can expect to have 17 different jobs across five different industries over the course of their careers.3 If job loss and change are the new normal—and they are—how will we ever learn to navigate our long career arc if we tether ourselves to a singular occupational identity? How do we let go of—or at least rethink—this obsession with career identity? We have to start young. Adults are always asking kids what they want to be when they grow up because they are looking for ideas. —Comedian Paula Poundstone It's no wonder that we ask adults “What do you do?” when we learned at an early age to connect with a future career identity. No doubt intended innocently enough to encourage a child's curiosity and aspiration, that question has become almost toxic as a device for focusing young children on realistic futures. Not too long ago, Heather was talking to her then four-year-old niece Izzy about her day at preschool. The next day, Izzy told her, was career day and she was having trouble deciding what she would be because her teacher had told her that her idea about “being a unicorn” was not realistic. Do we really need to ask children as young as four to decide on a realistic future self, especially when the world is changing so quickly that we may not yet even be able to imagine most of the future careers and even whole industries that will be options for today's preschoolers? Technological change will, in the words of IBM CEO Ginni Rometty, “reshape 100% of jobs.”4 Even if a youngster could tell you what she wanted to be when she grows up, it's likely that many tasks that job requires today will have been automated or re-formed completely by the time she's ready to earn her first paycheck. Instead, we should be encouraging children's curiosity. Rather than asking what a child wants to be, let's ask what they like to do. Let's probe about the one thing they learned today and why that one thing was special or interesting. Let's free their imagination to envision a life and a planet that is full of possibility. What might that look like? What doors might open that we didn't even recognize were there? Let us simply ask children what they are curious about while encouraging them to develop their interests and areas of strengths. So much of primary school in the United States focuses on the standardized tests that measure what a child does well—or worse, not so well—that children begin to form lifelong personal narratives long before they explore possibilities for their lives. Worse, early negative assessments cut off future exploration and limit individual and collective potential. “I am bad at math,” for example, shuts down many career paths and now, especially, at a time when quantitative reasoning is essential. Encouraging curiosity, purpose, and passion will set young people on a path of lifelong learning. Such encouragement, more than test scores alone, will unlock potential and prepare children to learn and adapt across their now much longer career arcs. What we are really talking about here is agency, the capacity to act independently on one's own behalf. Agency is the opposite of hopelessness. Agency fuels the adaptation advantage. Between “what do you do?” and “what do you want to be?” is one more question that we need to disrupt. Stop and think about your high school experience. How much of what you do today can you trace back to what you learned then or how you performed on some standardized tests? Now consider what young people today do in a world that is racing faster than the one you grew up in. We ask high school juniors and seniors to choose a focus of university study as part of the college application process. They step onto campus with the thinnest slice of experience and yet they are already tracked into coursework that is aimed at a specific, predetermined job that well might direct the remainder of their lives. Faced with the requirement to declare a major at the outset of post-secondary education, young people turn to familiar touchpoints to shape—and quite possibly limit—their future. Relying on high school experiences—“I'm bad at math” or “I love my French class” or “I hated my history teacher”—sends students looking for comfort, rather than challenges. Opting for areas of study that mimic the careers of parents’ or parents’ friends brings social acceptance. Falling prey to the influence of media provides a kind of endorsement of their choices. A 2009 study, for example, found the number of students majoring in forensic or crime scene science doubled over a five-year period and fully a third of those students were influenced by the popular CSI: Crime Scene Investigation television franchise.5 The social mobility implications of these influence-driven career choices are immense. Choosing a future self from the portfolio available in a child's family and social structure serves to replicate the conditions of that structure into adulthood. A child raised with high socioeconomic status will have a broader range of opportunity from which to select simply because they have been exposed to more options and had more aspirational and advanced professions modeled for them. Conversely, a child who grows up without socioeconomic advantages may see a much smaller world of opportunities. We can't break this cycle with a school system that screens students on a narrow set of skills and aptitudes, particularly when a child is the first in the family to attend university. How can these students see themselves in a field unfathomed by their family and community and unexplored in high school? Similarly, if you come from a long line of doctors or lawyers or fill-in-the-blank professions, it may be hard to imagine a self beyond the family business or the limits of the high school appraisal. Worse, following family footsteps has catastrophic potential as long-standing jobs and industries fall to automation and outsourcing. Imagine being the first in generations to reach for a career in an industry that has sustained your family for decades and longer only to find there is nothing to grasp. University students commit to mortgage-level debt to pursue these monolithic degrees. A rigid curriculum, course sequencing, and class scheduling often push what was intended to be a four-year degree program to five or six years, increasing the cost of that degree by 25 or 50%. Recognizing this challenge, the National Center for Education Statistics now tracks graduation rates at six years for what has traditionally been a four-year degree. And what value is that degree? A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that only 27% of the people they surveyed work in the field of their undergraduate major.6 Still, we myopically focus on the college major and push the decision earlier and earlier in the student's academic career, and with greater pressure. We tell students to pick a good major to get a good job in a good industry to climb a vertical career ladder. That ladder is gone. Good grades in high school may be an indicator of university completion rates, which itself might be an indicator of future earning potential. But let's be clear: good grades in a “good” major do not guarantee a “good” job. Instead, shifting focus from a specific course of study or degree to a broadly applicable set of skills sets students up for success. The Emerson Collective's XQ: Super Schools initiative is one of many emerging efforts to redesign the high school experience to better prepare students for a dynamic and rapidly shifting future. After a national listening tour, the Initiative established a set of “learner goals,”7 including:

Khan Academy, a nonprofit initially online-based learning company, launched the experimental Khan Lab School (K–12), where students are organized by independence level rather than age. They move through competencies rather than calendar years or standardized tests, and each student is required to teach as well as learn to reinforce their capabilities. Each student has a passion project in addition to their core coursework and teaching responsibilities. Collectively, these efforts communicate to students that they must have agency in life and specifically that lifelong learning is their responsibility. Connecting learning to purpose and passion is a means to self-fuel that learning. And, they establish an ideal foundation for lifelong adaptation. The PAST Foundation takes a different approach by providing a place for experimentation outside the structure of a school system. Founder Annalies Corbin describes the PAST Innovation Lab, which opened in 2016, as an education R&D prototyping facility. “We opened the lab so that we could specifically test the boundaries of the work/school interface,” she told us. “By fully embedding teaching and learning in industry R&D, startup, and launch, we saw exponential growth in students grasp of what is possible. Thus far, we have found when no longer constrained by the limits of traditional high school, students in the PAST lab excelled. They found the connections between industries and application and they are able to contribute to solving real-world challenges in real time as full active members of design teams. Our kids are only constrained by the limits of their own knowledge, which grows daily.” The PAST lab has embedded the adaptation advantage into their learning platform. These three examples are compelling experiments in creating the new foundational skills and abilities that will be necessary to navigate in this new world, and not just for high schoolers, but for everyone. When we define ourselves by what we do, our childhood aspirations, and our academic study, we are constructing our identity from dangerous materials. These rigid building blocks fix in place who we are and, more importantly, who we are not. If these are the bricks of occupational identity, however, it is a deeper and long-running narrative that is the mortar between them. Our notion of who we are, our identity, is formed by our explorations and, so often, by what we are told to believe about ourselves. As occupational and personal identity have become conflated, it's important, then, to take a step back and look at how personal identity is formed. There are two predominant theories on how our personal identities are formed. The first is the identity status model, originally proposed by developmental psychologist Erik Erikson and later refined by psychologist James Marcia.8 The second theory is the narrative identity theory proposed and developed by Dan P. McAdams.910 Identity formation, notably personal identity formation, primarily begins in adolescence and likely continues throughout your life, identity experts say. Gender and racial identity formation already start in childhood. The identity status model involves exploration of and commitment to one's sense of self. In this process of discovery, you pass through, and often land on, one of four distinct statuses:

Maybe you accepted your parents’ religious or political views without exploring your own values or you adopted their favorite sports teams without question. If so, these parts of your identity are foreclosed, according to the identity status model. Or maybe—as we have—you challenged your family's beliefs, causing them to shift from a foreclosure status to a moratorium or achievement status. As openly gay women and professional women often navigating male-dominated fields, we experienced not only our own change from moratorium to achievement, but also that of our parents, who reexamined their own religious (in Chris's case, her father was an ordained United Methodist minister) and social beliefs. The point is this: identity needn't be set in concrete. New information can guide us from one status to another in this model of identity. In fact, Theo Klimstra, PhD, associate professor at the Tilburg School of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Tilburg University and an identity specialist, believes we are “never done with our identity formation,” especially in today's society where so many factors are called into question by external changes. Indeed, our ability to navigate and reformulate our changing identity is core to our adaptability. The second major theory on the development of personal identity is the narrative approach, which McAdams cast as the life story model of identity. This theory proposes that we form our personal identity by creating our own narrative and memories of self. Those whose stories contain more references to meaning-making, research suggests, have higher levels of happiness. And while there is no commonly accepted research to prove the point, we can't help but wonder if this meaning-making might also lead to more satisfaction and engagement with work. Narrative experts do, however, believe that more and deeper reflection helps us make connections to meaning. Considering all these facets of narrative identity theory, we have an obligation to ourselves to identify the source of the stories that shape us. And as organizational leaders, we have the opportunity to make self-reflection an important tool as we support our workers as they develop and adjust their occupational identities. We will take a closer look at these concepts in Chapter 9, including the ideas of managing the impression others have of us as leaders and vulnerability as strength in leadership identity. Identity need not be static. Yet how often do we cling to a story of our past self at the expense of our future selves? Once again we recall Dan Gilbert's insight that we remember more easily than we imagine. How often do we hear our work and social cohorts brag about now long-gone glory days? Do they go on about their successes in high school or college sports? Are they still glowing in the early praise that they were smarter, better looking, or more charming than others, even as those attributes have faded or the competition against which we were judged has become so much greater? That is an identity trap, the formulation of a self-image based on a moment in time. As we consider the speed of change coupled with the lengthening of our life spans, we will be devoured by these traps if we don't learn to recognize and avoid them. We don't have to get stuck, though; instead, we can learn and adapt to reinvent ourselves time and again. Our identities begin to take hold when we believe the narrative we are told—directly and indirectly—about ourselves. Dr. Klimstra told us a story of his early career to make this point. As one of the only men in a cohort working in developmental psychology, he was often asked by both fellow (usually female) students and professors to be a study partner on quantitative subjects like statistics. Professor Klimstra had no particular quantitative prowess. He was just the lone male student, who others assumed would be skilled in this learning. Professor Klimstra admits now that he worked harder on those subjects so that he wouldn't fall short of the expectation that others had of him. As a result, he did well in those subjects, and it redirected his career from practice to research. Chances are good that something like this has happened to you. Somewhere along the way someone told you that you were good at something and you worked hard to realize that expectation. Or worse, you were told that you could not do something, so you never even tried. Identity traps begin in narrative, then take on many different forms. These traps hinder adaptation. Much like Professors Klimstra's experience, perhaps the most influential narrative given to us is our understanding of gender roles. Yet there is a profound disconnect between competence and confidence. Dozens of studies from organizations as diverse as Goldman Sachs to Columbia University have found that companies that employ women in large numbers outperform their competitors on every measure of profitability. At nearly every level of academic achievement, women outpace men. Women now far outnumber men among recent university students in most industrialized countries. For the ninth straight year, the Council of Graduate Schools (CGS) reports that for every 100 men who earn a doctoral degree at US universities, 137 doctoral degrees are awarded to women.11 Since 1981, more women have earned master's degrees than men. For every 100 master's degrees granted men, 167 go to women. For every 100 bachelor's degrees going to men, 120 are awarded to women. You might think that after decades of academic acceleration, women would make headway in achieving leadership positions in the workforce. Women now compose 47%12 of the US workforce in general and 50% of the workforce with at least a bachelor's degree.13 Still, women account for just 5% of the CEOs of S&P 500 companies and 6.6% of Fortune 500 companies. Women are achieving professional credentials at higher rates than men and studies prove that having more women in the workforce leads to better company performance. Still, the proportion of women in leadership roles is abysmal. So, where's the disconnect? Slow social change is one answer, but there's likely something else: the way we socialize gender. For nearly 50 years, girls have outperformed boys in academics. In “Leaving Boys Behind: Gender Disparities in High Academic Achievement” (National Bureau of Economic Research 2013), researchers identified a gender gap in GPAs among high school seniors of about 0.2 between 1976 and 2009.14 Then, girls began earning even higher grades, pushing the trendline up as more young women reported plans to attend not only university but, specifically, to pursue advanced degrees.15 Perhaps one way to account for this difference is the guidance we give to boys and girls. Boys are often praised for their performance as is. Girls are told they need to be better, perfect even, if they are to compete with boys. It's a narrative that creates a persistent insecurity. A 2015 report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) entitled The ABC of Gender Inequality in Education found that boys spend one hour less per week on homework than do girls, resulting in a Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) score that is, on average, four points lower for boys than girls.16 At a recent talk, Heather shared this research and hypothesis with senior executives for a large international hotel chain. After the talk, a female executive took her aside. “I do this,” she said. “I don't know why I do this, and I never realized I am part of the problem. I have two children close in age. When my son brings home a test score of an 85 (out of 100), I figure that is good enough considering he was probably tired. When my daughter brings home an 85, or even a 95, I ask her why she did not study more. I know how hard I had to fight to make it up the career ladder as a woman in this industry. I guess I am figuring my daughter will have to fight as hard, but I did not realize I was eroding her confidence in the process while bolstering my son's.” Confidence is key to adaptation. In the summer of 2019, 24 people—six women and 18 men—launched campaigns to become the Democratic nominee for the 2020 presidential race. By almost all measures, former vice president Joe Biden was the early frontrunner and considered the most electable candidate, even though he had twice lost his prior bids for the nomination. Of the six female candidates, all but one had been elected repeatedly and often in hotly contested districts. The other 17 male candidates offered a mixed bag of political success, yet most of these were considered viable candidates. The constant refrain among pundits of all political stripes was consistent: “Is she electable?” “Can a woman win?” Maybe these comments are echoes of Hillary Clinton's loss in 2016. Or maybe we simply continue to believe an ancient narrative. Let's consider what happens at work. A Hewlett-Packard internal report, quoted in Lean In, The Confidence Code, and dozens of articles, looked at the rates of promotion between men and women throughout its organization. Men, they found, put themselves forward for promotion when they had 50 to 60% of the skills required for the job. By contrast, women waited until they had a full 100% of the skills. Or, to summarize another corporate study by the Catalyst Foundation, “We promote men for potential and women for accomplishments.”17 Still, we have to ask: Why the confidence gap? Writing for The Atlantic in May 2014, journalists Katty Kay and Claire Shipman explored what they called “The Confidence Gap.” An extensive review of research into perceptions of competence and confidence, the article posited that women are encouraged to gain competency, whereas men are encouraged to gain confidence. Further, for women to succeed in jobs and careers, they must fill the confidence gap. In short, school systems are competence factories for females and confidence foundries for males, resulting in unequal foundations for adaptation. To make their point, Kay and Shipman leaned on the 2003 study by Cornell psychologist David Dunning and Washington State University psychologist Joyce Ehrlinger,18 who looked at both confidence and competence in professional women to correlate the relationship between one's perceived competence and one's confidence in a job was well done. The researchers asked male and female students to rate their perception of their scientific skills before taking a quiz on scientific reasoning. Perhaps not surprisingly to many, women rated their skills more modestly than did men, rating themselves 6.5 on average on a 10-point scale, while men rated themselves on average at 7.6. Asked how well they thought they did on the quiz, women thought they scored 5.8 of 10; men thought they got 7.1 answers correct. In fact, their test scores were almost the same: women answered 7.5 questions correctly and men scored slightly better at 7.9 correct answers on average. The lack of confidence extended beyond the quiz-taking for women. When offered the opportunity to compete for prizes in a science quiz prior to knowing their results, the women passed on the opportunity 51% of the time, compared with men, who declined only 29% of the time even though their scores were almost identical. Dunning and Ehrlinger are not alone in their findings. The Atlantic article goes on to highlight the work of Brenda Major, a psychologist at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Major's findings were consistent with those of Dunning and Ehrlinger. When presented with a series of tasks and asked to predict how they would perform on them, women regularly underestimated their ability and their performance. The opposite was true for men. “It's one of the most consistent finding you can have,” Major tells the article's authors. If you consider these research studies together, you'll see the systematic challenge: differing expectations and standards for males and females are quite literally coding the confidence gap—and, by extension, the adaptation potential—inequitably by gender from cradle through career (Figure 5.1). Figure 5.1 How We Build Competence and Close the Confidence Gap for Girls and Women Data sources: “Leaving Boys Behind: Gender Disparities in High Academic Achievement” (National Bureau of Economic Research 2013); Katty Kay and Claire Shipman, “The Confidence Gap”; 2003 study by David Dunning and Joyce Ehrlinger; Hewlett-Packard internal employment study. Not surprisingly, inequity cuts across race and is pervasive in hiring standards, too, as Dr. Vivienne Ming found in her research. Ming mined data from 122 million LinkedIn profiles to isolate two names—Joe and José—that, while similar-sounding, are commonly associated with White and Latino men, respectively. She then zeroed in on a single job function, “software developer.” With a final data set of 7,105 Joes and 4,896 Josés, she found that to hold the same job, José most often needed a master's degree and that Joe did not require even a bachelor's degree. The difference in standards is quite literally what Ming calls the tax on being different.19 If, as the Narrative Identity Study suggests, we embrace identity through the stories we are told about ourselves and others, then collectively we are socializing a confidence gap in women and the achievement gap in minorities to the detriment of business and social benefit. We believe what we hear, and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. And it is a tragic loss of human potential. If Professor Klimstra is right that our identity formation is never really complete, we ought to become more intentional about our explorations and narratives as more and more external factors are called into question. As we spoke to Klimstra for this book, he mused that white males, who in most Western societies enjoy the highest privilege and status, may have never explored many aspects of their personal identity because their status based on race and gender was more likely to be assumed than challenged. White males are often channeled into higher-paying, higher-status jobs, while women are steered toward higher-caregiving, often lower-paying, jobs. Identity formation, Klimstra notes, is a negotiation between internal beliefs and observations on one side and on the other, external narratives, notably what people—including the media—tell you about yourself and others. The cultural and societal normative changes we talked about in Chapter 2 demand a continuous renegotiation of identity, and that will be particularly difficult for people who believe their status and privilege is slipping away. It is very difficult to learn and adapt when you feel your core identity is under threat. Learning and adapting requires a certain vulnerability and a comfort with not knowing. When long-given status is called into question by other races, other genders, and even by technology, it is very difficult to be vulnerable in order to adapt to a new profession or occupation. In a review of research on the effects of job loss, the What Works Wellbeing Centre in London found that job loss can take longer to recover from than the loss—through death or divorce—of a primary relationship. Job loss has financial implications, of course, but the greater effect on wellbeing is the impact of the loss on one's social and personal identity. Men, they discovered, are more impacted than women, and many folks never fully recover from the loss of a job. Consider where we started this chapter. Who are you if you are no longer a banker or a lawyer? How does your social status—real or perceived—change if you no longer work for that Fortune 50 company or blue-ribbon firm? What if the career path you chose is a dead end rather than a long road? These aren't just hypothetical questions, and they each point to a potential crisis in identity. In fact, the authors have seen the effects up close among their friends. Marie20 worked for nearly two decades as an investigative journalist for what she viewed as among the handful of prestige print outlets. Of her own accord, Marie left the organization to join a well-established broadcast news organization. The new job came with a very substantial bump in pay and the ability to shape the investigative news unit she had joined. But just two weeks into the job, Marie was in full-blown panic, thinking What if this fails? What if I cannot find my way back into the prestige print world? My new colleagues don't work at my pace. What have I done with my life? I should see this like a sabbatical or a learning tour, but if it fails, what will I do? These questions pour out of a job change–driven identity crisis. Charlotte,21 on the other hand, is a rare female in the male-dominated broadcasting industry. Her career has spanned nearly three decades with a major network. Like her peers who have spent their entire career with the likes of ESPN, ABC, and CBS, she has focused on rising in the ranks. These days, Amazon is actively buying the rights to sports broadcasts, so it is only a matter of time before Charlotte has to adapt to a change in her home base. But Charlotte gives sports production a broad definition. She's not concerned about who owns or licenses the production because, at the end of the day, an investment in good content is an investment in her production. Amazon has shown through their investment in entertainment media that they are willing to invest in quality. Charlotte has no qualms about working for Amazon. Between us, we know dozens of people who intended to make their careers in academia. Each was nurtured through a system of higher education that said their academic achievement and the ultimate award—a doctoral degree—would give them entry into an elite class of professionals. Our friends trod the path that promised a tenure track position and lifetime employment. Some were successful. Many others realized that dream wouldn't happen for them and successfully segued to other industries, adapting their skills and knowledge to adjacent markets from sales to marketing to educational product development to educational technology. Still others, unable to obtain the academic appointments their studies assured, have spent their careers stringing together adjunct teaching incomes. These friends so closely identify as college and university professors that they haven't been able to adapt their skills and knowledge to another context. These stories are not unique. No matter what your identity, your chosen path, your “what do you do,” you will one day need to learn and adapt. Whatever you do now, unless you are closing in on your target retirement years, is unlikely to be your last job. If you have been at the same job for five to seven years without a change, brace yourself; change is coming. If you lean into the change, follow your curiosity, continually update your skills, nurture your network, and with a market mind continually assess the landscape for an opening for your abilities, you will be just fine. You've found your adaptation advantage.

The Questions That Limit Our Identity

What Do You Do?

What Do You Want to Be When You Grow Up?

What Is Your Major?

The Identity Trap

How Identity Is Formed

Identity Status Model

Narrative Identity Theory

Narratives Can Trap Us in the Past and Limit Our Future

Gender, Narratives, and Identity

The Confidence Gap

Identity Is Never Done

An Occupational Identity Crisis Isn't Limited to Job Loss

Notes