1

The World Is Fast: Technology Is Changing Everything and Planting Opportunity Everywhere

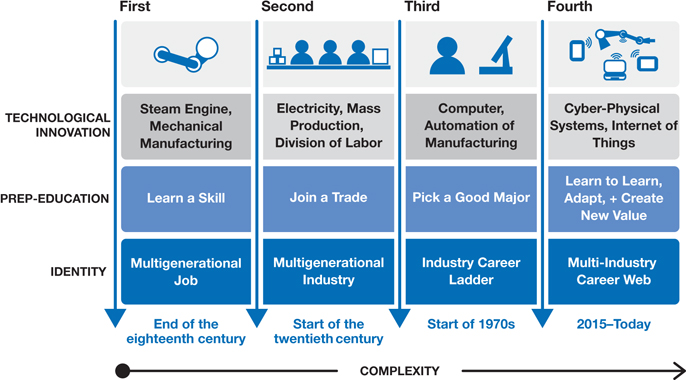

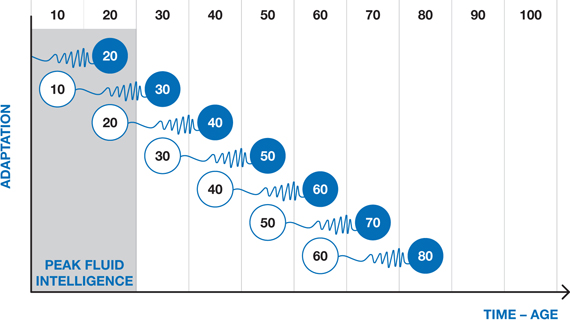

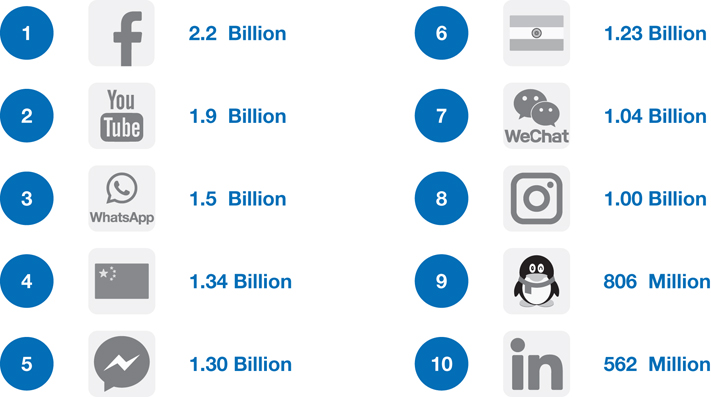

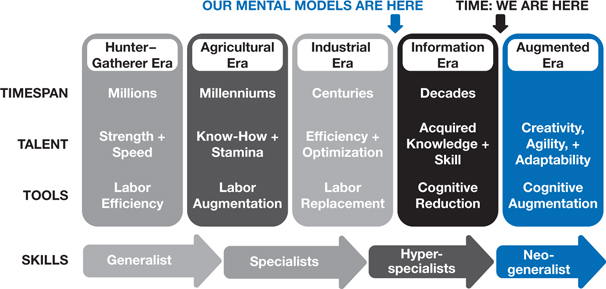

Key Ideas Change is coming at us with the greatest velocity in human history. In the single second it took you to read that sentence, an algorithm executed 1,000 trades. Computers at the credit card network Visa processed more than 1,700 transactions, no doubt a few of them providistockng payment for the 17 packages that robots helped pack and ship from Amazon warehouses. Right now, 76,000 Google searches are returning tens of billions of results links. Nearly 9,000 tweets and 930 Instagram photos have been added to an already overwhelming cloud of content. And at this very moment, more than 2.8 million emails are being sent, not all of them by actual humans. Technology is accelerating the pace of business at unthinkable speeds, so much so that the job you have today, the workforce you currently manage, or perhaps the job you are training or studying for now is changing as quickly as you read this page. In the next 18 to 24 months, the job you have today—if, indeed, it still exists at all—will be very different from what it is today. While technology experts from many different disciplines offer widely different views of the jobs gained or lost in a newly automated economy, IBM CEO Ginni Rometty captures the impact succinctly: “I expect AI to change 100 percent of jobs within the next five to 10 years.”1 Despite this reality, our contemporary views of education, career, workplace advancement, and even retirement continue to plod along at a horse-drawn-carriage pace. If we can barely imagine a one-second's-worth digital deluge, how will we get our heads around the implications for so much change, let alone adapt to it? While it's true that we are in the midst of the greatest velocity of change in human history, speed is only part of the problem. Change is coming at us from all sides. It's not just technology that's changing work; dramatic shifts in society and global economics are shaking up our worlds. And we've got to deal with them all at once; we've got to become adaptive. We are entering the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The First Industrial Revolution was marked by the steam engine, the Second by electrification and the division of labor for manufacturing, the Third by computerization and the beginning of automation of physical labor, and now the Fourth by the merging of biological and cyber systems into a fully digitized economy. In this push to a digital world, any physical or mental task with a predictable, repeatable outcome will be handled by an algorithm. Objects will contain sensors connected to networks where data drives decisions in real time. Many aspects of the biological world will be augmented by robotic and cognitive technologies. In this world, our relationship to work is no longer a monolithic career based on a single dose of early learning and compiled experiences. Instead, our careers will be defined by a state of constant learning and adaptation as new technologies, applications, and data alter the current state (Figure 1.1). Figure 1.1 The Fourth Industrial Revolution Celebrated New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman perfectly captures this moment in history in his most recent book, Thank You for Being Late. In it, Friedman argues that we are being buffeted by three simultaneous and interlocking “climate changes”: technology, the environment, and the global economy. These changes, he suggests, are rapidly reshaping our world. In 1965, semiconductor pioneer Gordon Moore posited that the capacity of a silicon processing chip would double each year, writing in the journal Electronics that “there is no reason to believe [the rate of change] will not remain nearly constant for at least 10 years.”2 A decade later, Moore revised his forecast, predicting that processors would double in capacity every two years throughout the next decade. Moore, it turns out, was not nearly far-sighted enough. More than 50 years later, Moore's Law continues to hold, even as the price of these now high-capacity processors continues to drop relative to their capabilities. It's difficult to imagine the impact of Moore's Law, but consider this: the smartphone you no doubt carry everywhere has 100,000 times more computing power, 1,000,000 times more memory, and 7,000,000 times more storage than was aboard the Apollo 11 spacecraft that carried astronauts to the moon. Yet even that comparison doesn't fully capture the impact of exponential change in computing technology, so imagine this: if the Volkswagen Beetle progressed along the same trajectory as semiconductors, that car today would be able to travel 300,000 miles per hour, get 2 million miles per gallon, and cost just four cents. There is yet another way to understand the impact of technological change, however: the change that we are absorbing at work. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, professionals entered a workforce where the Internet had little commercial impact, software came on floppy disks, a mobile phone was the size of a brick, social media was an evening book club, and artificial intelligence was science fiction. These people could expect to climb a corporate ladder, be paid a 401(k), and retire comfortably after 2030. If that sounds like you, and you are reading this book as it was published a full decade before that milestone, you know that work has changed, and that you will need to change with it. You will need the adaptation advantage. A Note about Artificial Intelligence From sci-fi depictions of autonomous robots with a “mind” of their own to Apple's Siri answering our most basic questions, artificial intelligence (AI)—in pop culture and reality—has endured more than 30 years of hype, yet still comes up short of the bold promise of a broadly “intelligent” computing system. Artificial intelligence is not one but dozens, if not hundreds, of component technologies. Throughout this book, we use the term “artificial intelligence” to discuss computing systems that are able to execute well-defined cognitive tasks. When a problem is specific and bounded, artificial intelligence techniques can solve it rather well. In truth, a general AI—one able to fully mimic the complex thinking and manage the rapid context shifting of the human brain—is far from realized with today's technology. Rather than AI, we tend to think of this capability as silicon or artificial cognition, and we use that reference from time to time in this book. But when it comes to computer systems taking on the cognitive tasks once exclusively the domain of humans, tasks that are very tightly defined and with outcomes predictably certain, we use the commonplace, if imperfect, artificial intelligence or AI. Today's new workers were “born digital,” grew up programming, carried their mobile phones to elementary school, and are beginning to think Twitter and Facebook are passé. Where technology-driven productivity shifts were once absorbed across a lifetime, allowing workers to adjust at pace, they are now on an exponential growth curve where change drives workers from job to job, employer to employer, and career to career. How we adapt to this much change may well be determined by our age. Science is just beginning to understand how our brains change with age, but most agree that fluid intelligence—our ability to rapidly and easily adapt to constant change—peaks at about the age of 20. Why does that matter? Well, if you were 10 years old when Internet technology became mainstream, you adopted smartphone technology at about the age of 20. Your parents, and especially your grandparents, met the challenge of this change much later in their lives. Adapting to ubiquitous wireless communications at 50 or 70 is a very, very different cognitive lift (Figure 1.2). Figure 1.2 Age and Adaptation There is no reason to believe that the pace of technological change will slow, and we're going to need new skills to stick to the pace. Human adaptation has long been linear, each step equal to the last. Technology expands exponentially, each step twice the size of the one before (Figure 1.3). In fact, by all estimations, the slowest rate of change you will experience for the rest of your life is … right now. Figure 1.3 Human Adaptation Is Linear, Technological Change Is Exponential Your work life will be one of constant adaptation. Every time you hand off a skill to technology, you must reach up to add capacity to your arsenal. We'll come back to this again and again throughout the book, but for now just let that idea set in. Understanding the need for continuous adaptation is the first step in achieving the adaptation advantage. While politicians may debate the cause of and response to environmental climate change, scientists aligned to academies, governments, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) around the world are clear on one point: our natural environment is changing at a rate faster than at any time in the past 7,000 years. Eighteen of the 19 warmest years on record have occurred since 2001. For millennia, CO2 levels had remained below 300 parts per million, until the 1950s, when atmospheric carbon dioxide surged to its current level of 412 million parts per million, their highest level in 650,000 years, according to NASA scientists. The effects of environmental climate change increasingly are becoming evident. Sea ice is melting, contributing to sea level rise. In 2014, the global sea level topped 2.6 inches above the sea level of just 20 years earlier. Scientists at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) predict that seas will continue to rise at a rate of about one-eighth of an inch per year, contributing to coastal erosion, devastating storm surges, and deeper in-land flooding. In some regions, growing seasons will be longer. Others will face devastating drought. Hurricanes will be stronger. Heat waves longer. And the Arctic Ocean is expected to be ice-free by mid-century. This environmental climate change, the New York Times’ Friedman contends, is fundamentally reshaping our geopolitical and economic foundations. And while you might not directly link environmental climate change to work, the effect of shifting climate will have a profound impact on human habitation. The World Bank predicts that as many as 143 million people will become “climate migrants,” leaving parts of the globe devastated by draught, floods, and failing crops. Within the typical span of a 30-year mortgage, nearly $120 billion of US housing stock will be at risk from chronic flooding, according to an economic report published by the Union of Concerned Scientists. In other words, your house may be underwater, even if your mortgage is not. Worse, that number skyrockets to more than $1 trillion by the end of the century. Many of America's largest cities, including New York, Boston, Miami, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, are in grave jeopardy from sea-level rise, suggesting a profound disruption of the country's economy and, by extension, its workforce. Scientists at the United Nations predict that we have just 11 years to make the significant changes necessary to avoid catastrophe. There is no more kicking the can down the road. We can't just decide to deal with it later. As Friedman says, “Later is over.” In its annual survey of CEOs in both 2018 and 2019, PricewaterhouseCoopers found that executives view climate change as the leading threat to business. Similarly, the World Economic Forum found that environmental risks account for three of the top five risks believed by executives to be likely to occur and among the top four risks believed to have the greatest impact on business. Every company will soon be forced to adapt to avoid catastrophe or adapt to catastrophe itself. There is no denying that this will reshape how and where work is done. In the analog economy, global commerce moved only as fast as a ship could transport a container across the sea, and that container could easily be regulated, inspected, and taxed as it moved from port to port. Not so in the emerging digital economy. Bits flow across international boundaries at the speed of light. There are no ports of entry, customs inspections, or tariffs on digital goods. The adage “information wants to be free” may not always hold, but on the Internet, it certainly flows freely. Consider the speed at which Airbnb took off in Cuba after the US Embassy opened there in 2015. Within three months, the homeshare service listed some 2,000 accommodations. It would have taken years for even the most ambitious hoteliers to build that many rooms for tourists eager to visit the formerly off-limits island nation. The scale of global trading partners affects the pace of business growth, too. Uber grew quickly in the United States. When Uber took its ride-hailing service to Miami, the city reached 1 million riders in just two years. An important milestone, no doubt. When Uber entered the market in Shanghai, however, they hit the million-rider milestone in less than two weeks. Of course, countries with large populations offer more scale than smaller ones, but consider this. While China and India support the largest physical populations, they rank only fourth and sixth, respectively, when you consider the rise of digital communities. Facebook, YouTube, and Whatsapp all host larger populations on their social media platforms. And they amassed those populations in under four years, not over centuries of human population growth (Figure 1.4). Figure 1.4 Top 10 Populations in the World Facing a residential population decline, Estonia digitized its economy and became determined to grow virtually. For 100 euros, anyone can become a digital resident of Estonia and, by extension, the European Union. While an Estonian digital passport doesn't convey the social and tax benefits of the country or the EU, if you want to establish a presence in Europe, open a European bank account, and be paid in euros, you can become a digital citizen for about USD110. Best of all, the entire transaction is done digitally; you don't even have to travel to Estonia to become a part of the country's now growing virtual population. In fact, in just over five years, the virtual population of Estonia is growing significantly faster than its physical population. As worldwide economies cross the bridge from analog to digital, every part of global business—currency, credentials, contracts, collaborations—will be backed by and amplified by digital technologies. If the speed of digital commerce seems breakneck now, when less than 20% of the US economy has transformed to digital, just imagine the pace of a fully digitized, global economy. Nothing can slow digital flows. We now live in a world in which any company can tap into the human talent cloud to identify the highest-quality, lowest-cost actor (human or technological) for any given task. In this reality, you must focus on how you uniquely add value, leveraging but not competing with rising technology and your own access to the talent cloud. The effects of these three climate changes have far-ranging implications that demand we rethink our relationship to work, careers, and how we prepare for them. They demand that we recast our identities, not in a rigid mold but with a flexible framework. Again, the New York Times’ Friedman is instructive here. The three climate changes reshape our world across five dimensions: politics, geopolitics, community, ethics, and work (Figure 1.5). Figure 1.5 Friedman's Three Climate Changes Reshape Our World As entrenched as the US two-party political system seems today, Friedman predicts the concept of “left” and “right” politics will give way to an entirely new political system in order to provide effective and adaptive government in the face of complex changes. Our current, mostly binary choices—capital versus labor, big government versus small government—that define the left and right simply won't be relevant. Instead, these real and unstoppable climate changes will require a more nuanced and adaptive government if we are to adapt and thrive ourselves. Friedman predicts that the United States will need to craft a new political party that is circular and based on natural systems—in short, a political party that is adaptive to changing social and environmental forces. Moreover, our economy is interdependent with those of nations around the world, tying the United States to economic partners who are not always our closest allies. Where community once meant the people who lived and worked nearby, community has slipped physical ties to include the people we've connected and formed bonds with online, people we may never even meet in person. As data and automation take on bigger roles in our lives, we must become intentional about defining the ethical guardrails between society and autonomous technology. Humans face fuzzy decisions every day; most of us navigate complex social ethics and cultural mores to make those decisions as fairly and effectively as possible. How will we program autonomous technology to make humane choices? What code will give a driverless car, for example, the judgment to crash into a lamppost, potentially endangering its passenger, rather than hitting a pedestrian in a crosswalk? Will developers be incented to optimize their algorithms to favor business over workers? What data will we use to train machine learning systems without bias? These are the type of critical questions that humanists and technologists must work on together. And finally, there is work, arguably the dimension across which this shape-shifting has the greatest impact. More than political ideology, geopolitical economics, ethical technology, or even community affiliation, work is deeply personal. Work is deeply engrained in our psyche. It drives our sense of value, purpose, and identity. If work shifts, we shift. And shift it will. We have entered what is often referred to as the Fourth Industrial Revolution barely able to keep pace with the velocity of change. Prior economic transformations—agrarian to mechanized production, for example—were absorbed over many decades, even hundreds of years. An apprentice could enter a trade, master his craft across a lifetime, and pass those skills on to his sons and daughters. Family businesses thrived across generations, so much so that surnames, most notably for those of European descent, often described the family's work: Carpenter, Baker, Smith, Parson, and so on. In the past century, one might reliably begin and end a career with a single company, perhaps even performing the same job. If you were born at the time of the steam engine, you had two or more generations to absorb the impact of that change, but if you are born today you will have to adapt to three, four, or five paradigm shifts within a single generation—that is where the velocity of change meets our expansive human longevity, and this is why we need the adaptation advantage (Figure 1.6). Figure 1.6 The Velocity of Change Requires Adaptation That's no longer the case. Indeed, the market is now retiring the last generation to view longevity at a single company or even in an industry as a virtue. We are now well into an era where specialization gives way to neogeneralism and lifelong learning. We are entering the fifth era in human history, an era that overlaps and maps to pre- and post-industrialization. It gets a bit confusing, so let's sort it out. In the eras of hunter/gatherers and agrarians, humans needed a wide array of skills to subsist, let alone thrive. As the industrial era unfolded, humans could specialize, share, and trade their work. The information era shifted physical labor to knowledge work and drove even more specialization, storing up knowledge from classrooms and work experience. As we enter the augmented era in which we partner with sophisticated technology, knowing must give way to learning (Figure 1.7). The path through education, work, and on to retirement is no longer a straight line, if it's even a line at all. Human beings must adapt, and quickly, yet our institutions, workplaces, and work policy are firmly stuck in the past. If we continue to ignore the clear signs that the future of work is fundamentally different from the past, we'll find ourselves wallowing in unemployment, underemployment, and dispirited workers and workplaces. Figure 1.7 The Fifth Era in Human History Source: Concept of Augmented Era © Jeff Kowalski, CTO Autodesk. To avoid that fate, we must find a new path, one that loops through the traditional notions of work, learning, and retirement in a continuous and adaptive cycle. Where we once learned to work and then used that learning to build a career over decades, now we must work in order to continuously learn to recognize and embrace the challenges and opportunities that these climate changes present. Working to learn is the cornerstone of the adaptation advantage. That will be the biggest, most essential shift of all.

Wait a Second

Technological Climate Change

What Does This Mean for Your Work?

Environmental Climate Change

What Does This Mean for Your Work?

Climate Change of the Market

What Does This Mean for Your Work?

The Force of Three Amplifying and Interlocking Climate Changes

Notes