C h a p t e r 9

Module 1—The

Decision-Making Process:

Anatomy of a Decision

This is the first module in the decision-making training program. It lays a foundation for all that follows by introducing the subject of decision making and breaking it apart into the process that will be used for the training. It should be used with programs of any length and can also be used as a stand-alone.

Training Objectives

After completing this module, the participants should be able to

- list and explain the steps by which a decision is made

- explain the benefits of a structured decision-making process

- determine the relative importance of a decision.

Module Time

Module Time

- Approximately 2 hours

Note: The estimate of two hours includes time for a pretest, a learning check at the end, and time for the typical administrative tasks associated with starting a training program, such as individual introductions, laying out the schedule and ground rules, and so on. As in all modules of 90 minutes or more, a break is included.

Materials

- Attendance list

- Pencils, pens, and paper for each participant

- Whiteboard or flipchart and markers

- Name tags or name tents for each participant

- Worksheet 9–1: Icebreaker

- Worksheet 9–2: Decision Analysis Sheet

- Evaluation Instrument 9–1: Pretest on Decision Making

- Computer, screen, and projector for displaying PowerPoint slides; alternatively, overhead projector and overhead transparencies

- PowerPoint slide program (slides 9–1 through 9–22)

- This chapter for reference or detailed facilitator notes

- Optional: music, coffee or other refreshments.

Module Preparation

Arrive ahead of time to greet the participants and make sure materials are available and laid out to support the way you want to run the class. Test any computer equipment you will use in the session.

In chapter 2 you will find a needs analysis questionnaire (Worksheet 2–1). The needs analysis is optional but may be helpful to you as the trainer.

In chapter 2 you will find a needs analysis questionnaire (Worksheet 2–1). The needs analysis is optional but may be helpful to you as the trainer.

If participants have not filled out the questionnaire before this first session, you may wish to add 15 minutes to the agenda to allow time to present the questionnaire and have the participants fill it out. The timing as described below does not include the needs analysis.

Sample Agenda

| 0:00 | Welcome class. |

| Have slide 9–1 on screen as people arrive; go to slide 9–2 as you begin. | |

| Introduce yourself. | |

| Take care of housekeeping items (information on schedule, restrooms, expectations). | |

| Ask participants to introduce themselves or use Worksheet 9–1: Icebreaker (optional). | |

| Review agenda for the entire program. | |

| Ask for questions or concerns. | |

| 0:15 | Pretest. |

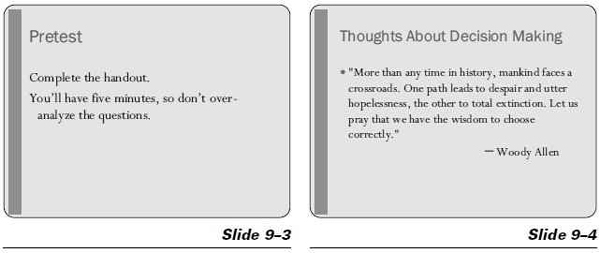

| Display slide 9–3 as the participants complete the pretest, then show slide 9–4. | |

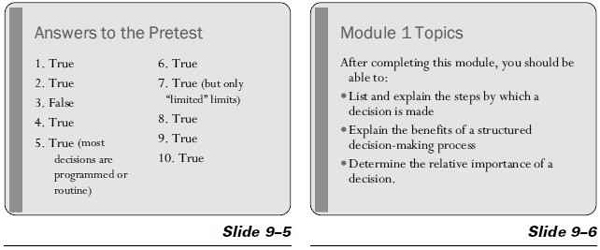

| Slide 9–5 has the answers to the pretest. Discuss as group. | |

| 0:30 | PowerPoint (PPT) Presentation. |

| Begin with slide 9–6 (objectives) and proceed through slide 9–15. See notes in PowerPoint file. | |

| 1:00 | Break. |

| 1:10 | Finish PPT. |

| Show slides 9–16 through 9–19. | |

| See notes in PowerPoint file and information below. | |

| 1:20 | Worksheets. |

| Distribute Worksheet 9–2: Decision Analysis Sheet. | |

| Show slide 9–20 as participants complete the worksheet. | |

| Move among participants to keep them on task. | |

| Group discussion—participants discuss answers with others. | |

| 1:50 | Wrap-up. |

| Show slide 9–21—a summary of the foregoing material. | |

| Ask for questions. | |

| Check learning (questions can be oral or printed—see below). | |

| Close with slide 9–22. |

Trainer’s Notes

Trainer’s Notes

8:00 a.m. Welcome (15 minutes).

![]() Show slide 9–1 as participants arrive. Welcome participants, introduce yourself, and take care of housekeeping items such as information on schedule and location of restrooms.

Show slide 9–1 as participants arrive. Welcome participants, introduce yourself, and take care of housekeeping items such as information on schedule and location of restrooms.

Show slide 9–2 and conduct participant introductions.

This can be done informally, or you may choose to distribute Worksheet 9–1: Icebreaker (optional). Instructions are part of the handout.

This can be done informally, or you may choose to distribute Worksheet 9–1: Icebreaker (optional). Instructions are part of the handout.

Discuss the purpose of workshop.

8:15 a.m. Pretest (15 minutes).

![]() Show slide 9–3. Distribute Evaluation Instrument 9–1: Pretest on Decision Making and explain how to complete the handout pretest self-assessment. Directions are on the worksheet.

Show slide 9–3. Distribute Evaluation Instrument 9–1: Pretest on Decision Making and explain how to complete the handout pretest self-assessment. Directions are on the worksheet.

Before you show the answers to the pretest, display and read slide 9–4 to begin the class with a smile.

Show slide 9–5. Discuss the answers to the pretest/self-assessment.

8:30 a.m. The Decision-Making Process (30 minutes).

Show slide 9–6 and discuss the learning objectives for the class.

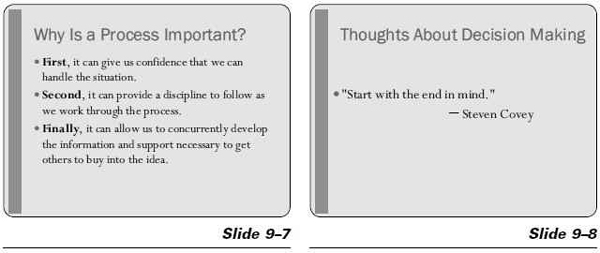

Show slide 9–7.

You might want to ask the participants the question before you show them the three reasons and see what they come up with. The pretest question 9 about making decisions in the “right way” is relevant to this discussion. Don’t just read the slide to them—you should paraphrase and discuss the points.

Show slide 9–8. Mention that Steven Covey is one of the best-selling business management authors of all time. Discuss why his statement is important.

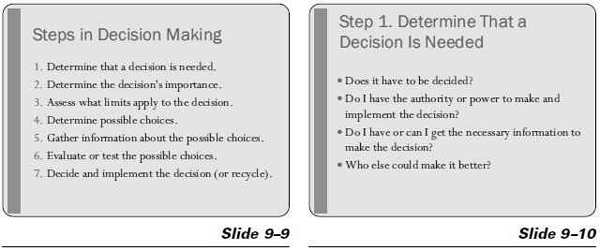

Show slide 9–9, which illustrates the steps in the decision-making process. Point out to the class that you will be going through the entire decision-making process in more detail, but that the structure outlined on slide 9–9 is the basis for most of the rest of the training program. Allow participants time to copy down the steps. (Kinesthetic-learner types, as well as visual and auditory types, will appreciate your suggestion.) You might also have the steps in a handout.

Show slide 9–10. Step 1: Determine That a Decision Is Needed.

Decisions are needed if actions are to happen in an orderly way. If you are responsible for making something happen, you must make decisions. Here are good questions to ask at this point:

Does it have to be decided?—What will happen if no decision is made? (Often the answer is that nothing bad will happen.) What pros and cons are there for inaction? Sometimes when minor issues are ignored, they die a natural death and . . . no one cares. If that’s the case, you can save yourself time and energy by not deciding.

Do I have the authority and power to make and implement the decision?—If not, why are you involved? Perhaps your reason for being involved is to recommend a course of action to someone else. Many staff people find themselves in this situation.

Do I have or can I get the necessary information to make the decision?—If not, you may as well throw a dart at a board listing all the choices. No use agonizing over it if there’s really no way to get the information that will tell you which of your options is best.

Who else could make the decision better?—If there is someone, why not let him or her make the decision?

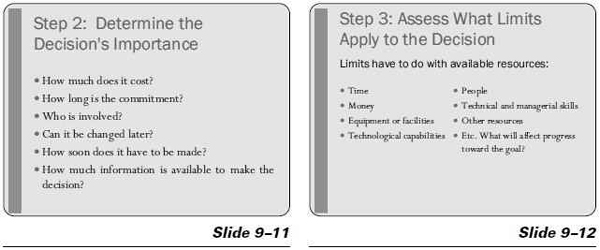

Show slide 9–11. Step 2: Determine the Importance of the Decision.

Decisions vary in importance: Dressing for a major job interview or social affair probably takes more thought than dressing to wash the car or the dog. Buying a house is a more important decision than buying socks.

Competent people intuitively know which decisions are important enough to merit more detailed processing (such as the process described in steps 3 through 7).

Most of us, however, know people who have difficulty making distinctions among the decisions they face—people who make all decisions seem equally important. These people usually frustrate themselves and others by agonizing over trivial decisions. You might say to the class that you will leave the analysis of why some people have this problem to specialists in human behavior. But for now, the class will consider the criteria most people use subconsciously to determine how important a decision is to them:

How much does it cost?—Importance usually increases with cost.

How long is the commitment?—Importance usually increases with the length of time with which one will have to endure the choice.

Who is involved?—Importance usually increases directly with the number of people involved and significance to the decision maker.

Can it be changed later?—Importance usually increases when it will be difficult or impossible to change the decision at a later time.

How soon does the decision have to be made?—Urgency and accompanying stress usually increase as the deadline nears. In one sense, then, importance may also increase. However, a decision may be urgent but still not very important. For example, the store may be closing. Do I need black or gray socks?

How much information is available to make the decision?—Although the information available may not directly influence the importance of the decision, it is a consideration. Either extreme—too much or not enough information—can increase stress.

Occasionally, however, we all goof in our estimation of a decision’s importance. We may think a decision is unimportant when it really is important, or vice versa. This usually happens because we weren’t aware of or didn’t pay attention to all the data. Of course, sometimes things change after we’ve begun the decision-making process.

Ask the class to think back to decision(s) they wrote down on the pretest. How do the points just discussed apply to those decisions? Allow them a minute or so to reflect quietly.

Show slide 9–12. Step 3: Assess What Limits Apply to the Decision.

Limits are usually defined in terms of resources available: time, money, people, and so on. It’s important to know these limits at the start, so the final decision takes those limits into account. Otherwise, the decision may not work.

Limits, also called parameters or conditions, are usually stated in terms of what resources the decision maker or the management of the organization is willing and able to apply toward achievement of the objectives. Therefore, when defining limits, you need to ask certain questions:

- How much time before the goal should be reached?

- How much money can be put toward its achievement?

- What equipment or facilities are available?

- What technological capabilities can be tapped?

- What people can be used? What technical and managerial skills do they have?

- What other resources are necessary?

- What will affect progress toward the goal?

The purpose of thinking through the limits is to reduce the number of options to be considered in the next step. For example, if your objective is to travel from Cincinnati to Chicago, you could do this in millions of ways. You could go by car, bicycle, plane, train, bus, or canoe. You could go through Indianapolis or Seattle or Paris.

By listing the limits before considering those routes, you reduce the pool of options to a practical number that can ultimately be viable. You could list other limits such as (1) getting there within one day and (2) having your own car to drive upon arrival. This, then, would limit your choice of options to fairly direct highway routes.

An important word of caution goes with this step: Don’t overdo the limits! Too many limits can reduce the potential for more creative options. Also, too strict limits may force you to focus too early toward some conscious or unconscious preconceived “best way” to accomplish your goal.

You need to set limits, but only those that are essential and absolute. For example, if above you say “MY car,” rather than “A car,” you’ve limited yourself much more. If you just need “a car” upon arrival, then going by plane, train, boat, or hitchhiking are still realistic options if you buy, rent, or borrow a car in Chicago. They might also be better or cheaper options, even with the additional cost of getting a car in Chicago.

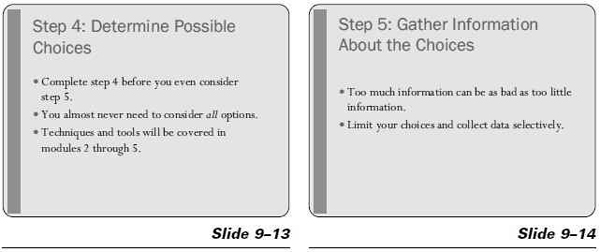

Show slide 9–13. Step 4: Determine Possible Choices.

Step 4 is the very important inductive or creative part of the planning process. It must be done effectively—that is, you must come up with a good list of options from which to choose—if you are to come up with an effective plan.

A discussion of ways you can develop creative options is part of a later module. However, two important points need to be covered here:

(1) Complete step 4 before you even think about step 5, and

(2) At this point you may not come up with all possible options. That’s OK.

It is important to isolate step 4 from step 5. For one thing, the two steps use different sides of the brain. Creativity is generally associated with the right side of the brain, whereas analysis skills reside in the left side.

Further, many of the tools discussed later in this program are associated exclusively with one step or the other. Jumping back and forth between these steps adds unnecessary complications to the planning process.

Finally, human nature isn’t always as patient as it should be. Flip-flopping between these steps will add time and probably increase pressures to cut the process short. The lesson is this: Don’t start to evaluate the options until you’ve come up with an adequate list of options.

What is an “adequate” list? It is one that (a) has been developed with enough thought that you’ve included several different kinds of options. This may mean different vendors or locations or styles, and so forth. And (b) the differences between options should be more than just cosmetic. For example, if your house looks dreary, your options should not be only between brands of white paint. They should include various colors, stains, aluminum siding, and bricks. Of course, you might eliminate some of these in the next step, but at least consider them.

To illustrate the hazard of jumping to step 5 without first completing step 4, consider the process of planning to buy a car: Objective: To buy a car by this Friday. Limits: $18,000; room for five passengers; four-wheel drive; and so forth (add limits to meet your personal needs).

If you go to the first dealer’s lot, see a car that fits the limits, and buy it without looking elsewhere, you may not have implemented the best plan. As you drive home in your new car, you may pass other dealerships and wonder if some of those cars might have been cheaper or better.

The other rule of thumb is not to go to step 5 until you have a minimum of four viable options. If four come fairly easily, go for a dozen. Use the car example again by noting that unless you live in a small town a long way from anywhere else you might buy a car, you’ll probably not consider every possible option before you make a choice. Somewhere between dozens and thousands of cars are for sale in most places. It’s neither possible nor logical to check out each and every one before you buy.

How many options are enough? It depends on the nature of the decision. A range of four to 12 options is adequate for most planning. Modules 2 through 5 will introduce you to a variety of ways to create a broader and more effective list of options.

Show slide 9–14. Step 5: Gather Information About the Choices.

Emphasize to the class that this step is the start of the deductive or data-gathering and analytical (that is, left brain) part of the decision-making process. Give an example by asking participants, “How many kinds of cookies are available in your local grocery store?” And ask them how much information can be obtained by reading the package of each kind of cookie. Finally, ask how a “logical” decision might be made with this information?

More about data collection will be covered in module 6, and more about the issues of too much information in module 9. Note: If your program will not include those modules, either don’t mention them or quickly summarize enough from those lessons to make their points relevant here.

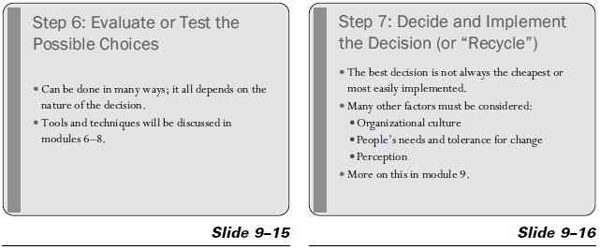

Show slide 9–15. Step 6: Evaluate or Test the Possible Choices.

This step continues the deductive part of the decision-making process.

Remind the learners that no option is ever perfect. Each option will have pros and cons. These pros and cons will be of different importance in the evaluation of the option. As decision makers, they will have to collect data on each option. How much information they need and where they get it will depend on what sort of decision they’re making.

Return to the example of buying a car. Tell the class that the choices have been narrowed down to six possible choices. All fit the price, size, and four-wheel drive requirement set in step 3. Now they must gather and analyze further information on each of the options.

They will probably have several sources for this information. One source will be the cars themselves—doing test drives, kicking the tires, and smelling the upholstery. Another factor might be the salesperson. Still others would be publications such as Consumer Reports or similar magazines and websites that objectively evaluate automobiles. Other, possibly important, sources include their insurance agent, Uncle Harry, their spouse, and Joe (owner of Joe’s Garage, who currently holds the mortgage to their house based on previous repair bills).

For a different sort of an example, let’s say you’re trying to hire a new employee. Goal: Hire an electrical engineer. Limits: $42,000 maximum salary; able to start work first of the month; must know about the industrial controls business. Options: You have received seven job applications.

Now you must evaluate these options (the applicants for the job). Undoubtedly, you’ll find pros and cons to each prospective employee. To decide which applicant to hire, you’ll have to collect more data on each and evaluate this data before you can make your decision. Later in the program, we will introduce a variety of tools and techniques to help you objectively review the list of options you’ve created and establish an objective, methodical means of evaluating each.

Note: If your program will not include modules 6 through 8, which cover methods for evaluating options, don’t mention that aspect. Instead, edit slide 9–15 to remove the reference.

9:00 a.m. Break (10 minutes).

9:10 a.m. Step 7: Decide and Implement the Decision (10 minutes).

Show slide 9–16. The results of the evaluation in step 6 may lead to an obvious choice. On the other hand, there may be no obvious choice. Although some narrowing of the field of options and further data collection may help, the fact is, most decisions are calculated risks. The subject of risk is also covered in the next module.

The “best” decision may not be the cheapest. Lots of other considerations need to come into play, and they’ll be discussed later in the training. For the moment, consider such things as the organizational culture, how big a change would be caused by your decision, how people might perceive things, and so on.

At this point you can implement the decision or recycle the decision-making process to a more specific level.

If the decision requires no further thought of great consequence, you can implement it. For example, if you’ve decided which engineering candidate you want to hire, do it. If you’ve decided which route to take from Cincinnati to Chicago, go for it. These decisions may be low-level enough that almost no further consideration is needed before you can put them into effect.

But perhaps you have a bigger goal: You want to start a business. In that case, maybe your limits in step 3 were the $50,000 you just inherited from Uncle Abner’s will and your own job skills. Your options could have included opening up a shoe store, buying a pizza franchise, and starting a computer maintenance service. Your evaluation of these and other options included the potential profit for each, competition, legal issues, and so forth, and your choice was to open a shoe store.

Opening a shoe store is not a plan that can be implemented right away. It needs to be supplemented with a number of other, lower-level plans. This means you’ll have to go back through the decision-making process several times. The decision of opening a shoe store has now become the new goal or objective for further decisions. You need to decide where to open the store. You need to decide how to advertise. You need to decide how to organize and staff the operation of the store. You need to decide how to obtain inventory. You may need to decide how to obtain further financing, and so forth.

So, you recycle through the decision-making process. A new, lower level, more specific, goal is to find a location for your shoe store. Limits would include geographic distribution of customers, costs of various locations (and whether to purchase or rent), and so forth. To determine your options, you call a commercial realtor or go through one or more of the processes in module 6. Your choice of a location may be a low-enough-level decision that you can just sign a lease to implement it. But you still have other specific plans to make about staff, inventory, additional financing, and so forth.

Note: Edit slide 9–16 to remove the last line if you will not be including module 9 in your program.

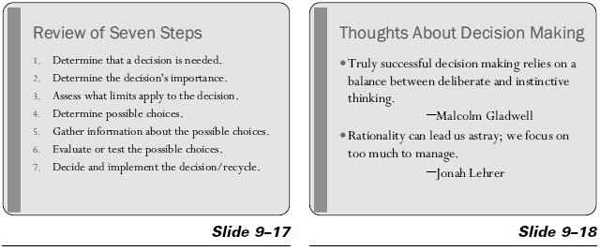

Show slide 9–17. Review of the Seven Steps.

Show slide 9–18. Thoughts About Decision Making. Read and discuss the quotes.

Show slide 9–19. Decision Making Isn’t All Logic.

Discuss the points on the slide. Tell the class that they know the truth of these points intuitively.

Note that several bestselling books such as Blink by Malcolm Gladwell and How We Decide by Jonah Lehrer spell out the scientific research that proves those points.

Too much information can cause us to over-analyze things, and we are apt to make worse decisions. Several studies have shown that decision makers do much worse than random chance when faced with trying to decide why they chose one jelly over another (out of a couple of dozen choices). We become overwhelmed and lose perspective.

The more complex a problem, the less we can rely on simple rationality. Even so, the process suggested earlier (and continued throughout this training) will help structure things into more manageable elements.

Golfers, tennis players, chess players, and experts in almost any area can ruin their game by thinking too much. Once you are an expert in something, you have developed subconscious and innate skills, and you need to trust them.

9:20 a.m. Application Exercise (30 minutes).

9:20 a.m. Application Exercise (30 minutes).

Show slide 9–20. Distribute Worksheet 9–2: Decision Analysis Sheet, and work with individuals to choose a decision/case to work on.  The decision needs to be a fairly complex one. Possible topics could be opening a new branch office, starting a new marketing campaign, making a major purchase (a house, another company), modifying a product line, or something of that magnitude.

The decision needs to be a fairly complex one. Possible topics could be opening a new branch office, starting a new marketing campaign, making a major purchase (a house, another company), modifying a product line, or something of that magnitude.

Note: Work with people to choose something appropriate as they begin this training. If they’re trying to choose which tie to wear to the fund raiser next week, they will not be able to apply the learning very effectively.

9:50 a.m. Module 1 Summary (10 minutes).

Show slide 9–21. Review the objectives covered in this module. At this point, you may want to preview the next module and announce any work to be done ahead of time.

LEARNING CHECK QUESTIONS

LEARNING CHECK QUESTIONS

You can use the learning check questions and answers in oral or printed form.

Discussion Questions

- Give examples of limits as the term applies to the decision-making process.

Answer: time, money, space, people, equipment, technology, and so forth. - Why is it important to separate step 4 and step 5 in the decision-making process?

Answer: They use different sides of the brain; flip-flopping wastes time and can encourage adopting the first workable answer, and so forth. - What is meant by recycle as one of the possible options in the last step of decision making?

Answer: Some decisions are small enough to implement without exhaustive research, but others provide the foundation for further decision making. For the latter, you need to recycle the decision-making process at a lower level. - Name three reasons why it’s important to understand the structure of the decision-making process.

Answer: It can (1) give the decision maker confidence, (2) provide a proven process, and (3) assist in gathering and developing necessary information in the most efficient manner. - List the steps in decision making.

Answer: Step 1: Determine That a Decision Is Needed

Step 2: Determine the Importance of the Decision

Step 3: Assess What Limits Apply to the Decision

Step 4: Determine Possible Choices

Step 5: Gather Information About the Choices

Step 6: Evaluate or Test the Possible Choices

Step 7: Decide and Implement the Decision - What are the potential problems (if any) with a decision being made the “wrong” way, as long as it results in an acceptable outcome?

Answer: Possible inefficiencies, including backtracking, false starts, and so forth. By doing it the “proper” way, you have a predictable pattern, you can develop documentation as you go along, and you can retrace your steps. Moreover, a well-defined process is generally likely to be more efficient and effective.

Multiple Choice Questions

- Which of the following is not directly related to a decision’s importance?

a. The amount of information is available to help make it (answer).

b. Who is involved with it?

c. Can the decision be changed later?

d. How much does the decision cost in comparison to budget? - Before facts relevant to the various alternatives can be gathered, one must first

a. Identify possible alternatives

b. Identify the problem

c. Select the best alternative

d. Both a and b (answer)

10:00 a.m. Thank You for Your Attention.

Show slide 9–22. Edit this slide to include information relevant to your class.

Worksheet 9–1

Icebreaker Instructions:

Pair off with someone you don’t know well.

You have three minutes each to exchange answers to the following questions.

Name?

How long have you been with the organization?

What’s your job title?

What’s the most recent significant decision you’ve had to make for the organization?

What hobby or family obligation (that you’re willing to share) takes up your time away from the job?

When the trainer gathers the group back together, you will be asked to take one minute or less to introduce your companion to the rest of the group.

© 2010 Decision-Making Training, American Society for Training & Development

Worksheet 9–2

In one sentence or less, specify the decision you need to make:

Is this decision necessary?

- What will happen if no decision is made?

- Are there advantages to not making the decision?

- What are the disadvantages?

- Do you have the authority and power to make and implement the decision?If not, why are you involved?

- Could someone else make this decision better than you?Who? ____________ Why don’t they?

How important is the decision?

- How much is the probable cost? _____________

How does that compare to your total budget? _________ - How long is the commitment? ____________

- Can it be changed later? ________________

How expensive or messy would a later change be? _______ - How soon does the decision have to be made? ___________

- Who else is involved? _____________________

What limits apply to this decision?

List all major factors that will affect or be affected by this decision:

PeopleEquipmentFacilitiesTimeCompetitionManagement skillsThe economyBudget, now and futureOthers

© 2010 Decision-Making Training, American Society for Training & Development

Evaluation Instrument 9–1

Circle either true or false:

| T | F | 1. We all make hundreds of decisions every day. |

| T | F | 2. All decisions are made in an essentially similar pattern. |

| T | F | 3. Choices should be evaluated as they appear. |

| T | F | 4. Decision making applies to all phases of management or supervision. |

| T | F | 5. Creativity is not necessary in most decision making. |

| T | F | 6. Intuition is more important than rational thought in the early stages of decision making. |

| T | F | 7. Limits should be established early in the decision-making process. |

| T | F | 8. Tolerance for risk influences decision making for managers. |

| T | F | 9. Good decisions are both properly made and effective. |

| T | F | 10. Organizational decisions tend to be more “convoluted” than “straightforward” in nature. |

List several decisions that you either have made in the past couple of weeks or you will need to make in the next several weeks. These will serve as the basis for discussion during this program.

© 2010 Decision-Making Training, American Society for Training & Development