8

Inside the Mind of the Protégé

When Fear and Learning Collide

Education is the ability to listen to almost anything without losing your temper or your self-confidence.

Robert Frost

Fear is as personal as a fingerprint. We have a daredevil friend whose idea of a fun Saturday afternoon is to bungee jump off a bridge or skydive from a helicopter. The thought of either makes us break out in a cold sweat. What frightens one person is another person’s playground.

Understanding the protégé’s emotional state, particularly at the start of the relationship, is an essential first step of creating an atmosphere of acceptance and trust. Keep in mind that fear is far more a liability than an asset where learning is involved. A testing, contentious learning environment may bring out the adrenaline but does not bolster aptitude. Learners who are fearful tend to take fewer risks. And protégés differ in what elevates their anxiety. What is the physiology of fear, and how can that knowledge serve mentors?

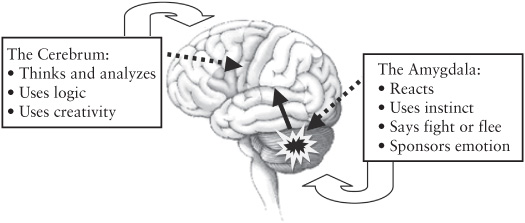

Let’s take a deep dive into the mind of the protégé—especially one at the most anxious end of the fear continuum. We begin with a review of what you probably learned in ninth-grade general science or tenth-grade biology about the workings of the brain. The brain is divided into many parts. We will focus on two key parts—the cerebrum and the amygdala (see Figure 2). The cerebrum is that big gray wrinkly part that we typically call the brain. It is divided into two halves (or hemispheres)—the right side is the intuitive, creative or emotional side; the left is the logical, analytical or rational side.

What does the cerebrum do? In its entirety it is the seat of logic, creativity, analysis, insight, learning, and problem solving. We humans have the largest cerebrum in relation to body weight of any species. In fact, the label Homo sapiens comes from the Latin meaning “wise or knowing man.”

And the amygdala? From an evolutionary perspective, it is one of the oldest parts of the brain and controls instinct and a person’s physical reaction to danger. Sometimes referred to as the reptilian brain (or, with a hat tip to Seth Godin, the lizard brain), it controls the fight-or-flight response and triggers the secretion of adrenaline—the hormone that gets dumped into the bloodstream to make us faster, stronger, and tougher when threatened. Adrenaline is not stored in the brain, but it is the amygdala that flips the switch causing its release. It is what makes your hair stand on end and enables all your senses to be much sharper and keener in a crisis.

When you experience anything in life, imagine the message taking two routes. The slower route goes to the cerebrum; the faster route goes to the amygdala (see Figure 2). The amygdala is connected to the cerebrum and acts much like an early-warning clearinghouse for any signs of threat. If the amygdala senses danger, it quickly sends a message to the cerebrum requesting it to ignore the forthcoming message (the slower-moving information). With that warning, the cerebrum mostly shuts down—sometimes as much as two-thirds of it—in order to allow the amygdala to deal with the threat situation in a reactive or instinctive way. In other words, evolution has enabled the brain to let instinct rule over logic in times of threat or danger.

Imagine a caveman out on a leisurely stroll when he suddenly encounters a mean, angry saber-toothed tiger. If the caveman thought to himself, “Let me figure this out. Seems to me I recall my father telling me if I saw one of these animals I needed to move to the left, no wait, I believe it was move to the right,” what do you think would happen? He’d be lunch to the tiger. So the brain learned that in saber-toothed tiger situations, we will live longer if the situation is dealt with instinctively and reactively rather than logically and rationally.

The brain works today much like it did then. Actually, today it is not the threat of physical harm that triggers the amygdala’s taking over for the cerebrum; it is the threat of emotional harm, which can range in severity from mild disappointment to downright fury. The more the sense of harm moves to the fury end, the more “victim” the protégé feels. The path to getting a good connection is to remember the protégé is not acting rationally but acting threatened.

What does being a victim really mean to a protégé? It could mean many things to a protégé: “I will appear stupid”; “I will lose composure or control”; “My embarrassment will be obvious”; “My mentor will harm my reputation”; “I will lose now but I’ll lose even more next time.” You get the idea.

The point is, when people go into this state, they are not operating out of their normal thinking brain. They are operating out of the world of fight-or-flight—they want to fight or flee. Since in the typical mentoring relationship, a fight (arguing, blaming, resisting, etc.) is not deemed an appropriate response, the protégé will opt to flee. This might not be literally running out of the room; it will more likely be reserve, extreme shyness, noticeable timidity, and posture that spells “defense.”

The most important point is that higher-level learning (as opposed to instinctive or rote learning like someone might use in boot camp) is acquired in the cerebrum (now dormant) rather than the amygdala, now in charge. The goal of rapport building is to invite the protégés out of their “terror” state to a more rational state where effective learning (a.k.a., risk taking) can occur.