Appendix A

Details of the Nine Prominent Federal Environmental Statutes

(Adapted from Lynch, 1995)

The Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) Of 1976

Incidents in which highly toxic substances such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) began appearing in the environment and in food supplies prompted the federal government to create a program to assess the risks of chemicals before they are introduced into commerce. The Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) was enacted in October 11, 1976. TSCA empowers EPA to screen new chemicals or certain existing chemicals to ensure that their production and use do not pose “unreasonable risk” to human health and the environment. However, TSCA requires EPA to balance the economic and social benefits against the purported risks.

Information Gathering

TSCA requires EPA to gather information on all chemicals manufactured or processed for commercial purposes in the United States. The first version of the “TSCA Inventory” contained 55,000 chemicals, and if a chemical is not found on this list, it is considered to be a new chemical and is subject to the Premanufacture Notification requirements. To aid in the gathering of information on existing compounds, companies that manufacture, import, or process any chemical substance are required to submit a report detailing chemical and processing information. This information includes the chemical identity; name and molecular structure; categories of use; amounts manufactured or processed; byproducts from manufacture, processing, use, or disposal; environmental/health effects of chemical and byproducts; and exposure information. Companies must also keep records of any incidents involving the chemical that resulted in adverse health effects or environmental damage.

Existing Chemicals Testing

TSCA may require companies to conduct chemical testing and then submit more detailed data to EPA compared to the information gathering activities listed above. EPA can request this additional data for chemicals that reside on a separate list compiled from the TSCA Inventory by an Interagency Testing Committee. Chemicals that become listed are typically either produced in very high volumes or they may pose unreasonable risk or injury to health or the environment. The list can contain no more than 50 chemicals and EPA is required to recommend a test rule or remove the chemical from the list within one year of its listing. Once a test rule has been promulgated, a regulated entity (a chemical manufacturer) has 90 days from the initiation of the test rule to submit the data.

New Chemical Review

Chemical manufacturers, importers, and processors are required to notify EPA within 90 days of introducing a new chemical into commerce by submitting a Premanufacturing Notice (PMN). The PMN contains information on the identity of the chemical, categories of use, amounts intended to be manufactured, number of persons exposed to the chemical, the manner of disposal, and data on the chemical’s effects on health and the environment. EPA can require a PMN to be submitted on any existing chemical that is being used in a significantly different manner than prior known usages. EPA has 90 day from the submission of the PMN to assess the risks of the new chemical or new usage of an existing chemical. If the risks are deemed to be unreasonable based on the information in the PMN and other data that are generally available, EPA is required to take steps to control such risks. These steps might include limiting the production or use of the chemical or ruling a complete ban of the chemical. If data contained in the PMN is insufficient such that EPA cannot make a determination of the risks, the production of that chemical may be banned until such data is made available.

Regulatory Controls and Enforcement

EPA has several options to control the risk of chemicals that have been deemed to pose unreasonable risk, ranging from banning the chemical (most burdensome), to limiting its production and use (less burdensome), to requiring warning labels at the point of sale (least burdensome). EPA is required to use the least burdensome regulatory control considering the chemical’s societal and economic benefits. This does not mean that the least burdensome control is always used, but rather it requires EPA to consider the benefits before applying regulatory controls. EPA is authorized to conduct inspections of facilities for manufacturing, processing, storing, or transporting regulated chemicals and items eligible for inspection may include records, files, controls, and processing equipment. “Knowing or willful” violations of TSCA are punishable as crimes that carry up to 1 year imprisonment and up to $25,000 per day of violation.

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, And Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) Of 1972

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act was originally enacted in 1947, but has been amended several times, most notably in 1972. Because all pesticides are toxic to plants and animals, they may pose an unacceptable risk to human health and the environment. FIFRA is a federal regulatory program whose purpose is to assess the risks of pesticides and to control their usage so that any exposure poses an acceptable level of risk.

Registration of Pesticides

Before any pesticide can be distributed or sold in the United Stated, it must be registered with the EPA. The decision by EPA to register a pesticide is based on the data submitted by the pesticide manufacturer in the registration application. The data in the registration application is difficult and expensive to develop, and must include the crop or insect to which it will be applied. In addition, the data must support the claim that it is effective against its intended target, that it allows adequate safety to those applying it and that it will not cause unreasonable harm to the environment. The use of the term “unreasonable harm” is equivalent to requiring the EPA to consider a pesticide’s environmental, economic, and social benefits and costs. Pesticides are registered for either general or restricted use. EPA requires that restricted pesticides be applied by a certified applicator. A registration is valid for five years, upon which time it automatically expires unless a re-registration petition is received. FIFRA requires older pesticides that were never subject to the current registration requirements to be registered if their use is to continue. It is estimated that there are over 35,000 older pesticides that were never registered during their prior usage. EPA can cancel a pesticide’s registration if it is found to present unreasonable risk to human health or the environment. Also, a registration may be revoked if the pesticide manufacturer does not pay EPA the registration maintenance fee.

Labeling

Labels must be placed on pesticide products that indicate approved uses and restrictions. The label must contain the pesticide’s active ingredients, instructions on approved applications to crops or insects, and any limitations on when and where it can be used. It is a violation of FIFRA to use any pesticide in a manner that is not consistent with the information contained on the product label.

Enforcement

It is unlawful to sell or distribute any unregistered pesticide or any pesticide whose composition or usage is different from the information contained in its registration. It is also a violation if FIFRA record keeping, reporting, and inspection requirements are not met. The use of registered pesticides that were approved for restricted use only in any manner other than stated on the FIFRA registration also constitutes a violation. Finally, it is unlawful to submit false data and registration claims. The power to enforce FIFRA is given to the states; however, the state implementation and enforcement programs must be substantially equivalent to the federal program. Any violation of FIFRA is punishable by a civil fine of up to $5,000 while knowing violations of registration requirements may have criminal fines of up to $50,000 and 1 year imprisonment. Fraudulent data submissions may be punishable by up to $10,000 or up to 3 years imprisonment.

The Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH ACT) Of 1970

The OSH Act was enacted in December 29, 1970 in order to ensure safe working conditions for men and women. The agency that oversees the implementation of the OSH Act is the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Each state is authorized to develop its own safety and health plan, but it may adopt the federal program and must meet all federal standards. All private facilities having more than 10 employees must comply with the OSH Act requirements, though certain employment sectors are exempt from the majority of the Act’s regulatory provisions. For example, excluded are certain segments of the transportation industry which are covered by the Department of Transportation regulations, the mining industry which is regulated by the Mine Safety and Health Administration, and the atomic energy industry which must comply with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission standards.

Workplace Health and Safety Standards

The OSH Act requires OSHA to set workplace standards to ensure a safe and healthy work environment. These include health standards, which provide protection from harmful or toxic substances by limiting the amount to which a worker is exposed, and safety standards, which are designed to protect workers from physical hazards, such as faulty or potentially dangerous equipment. When establishing health standards, OSHA considers the short term (acute), long term (chronic), and carcinogenic health effects of a chemical or a chemical mixture. These standards take the form of maximum exposure concentrations for chemicals and requirements for labeling, use of protective equipment, and workplace monitoring.

Hazard Communication Standard

The OSH Act’s Hazard Communication Standard requires that several standards be met by manufacturers or importers of chemicals and also for the subsequent users of them. These requirements include the development of hazard assessment data, the labeling of chemical substances, and the informing and training of employees in the safe use of chemicals. Chemical manufacturers and importers are required to assess both the physical and health hazards of the chemicals they make or use. This information must be assembled in a material safety data sheet (MSDS) in accordance with OSH Act standards and accompany any sale or transfer of the chemical. Chemical manufacturers and importers must also label chemicals according to OSH Act standards whenever a chemical leaves their control and must train their employees on the safe handling of chemicals in the workplace. Employers must keep a copy of the MSDS in the workplace for each chemical used. Employers must also develop a written hazards communication plan which outlines the implementation plan for informing and training employees on the safe handling of chemicals in the workplace. Employers that use manufactured chemicals must also label those containers according to OSH Act standards.

Record Keeping and Inspection Requirements

Employers must keep records of all steps taken to comply with OSH Act requirements, including the company’s safety policies, hazard communication plan, and employee training programs. In addition, employers must keep records of all work-related injuries and deaths and report them periodically to OSHA. Employers must keep records of employee exposure to potentially toxic chemicals and keep them for 30 years. An OSHA Compliance Safety and Health Officer is authorized to enter all covered facilities as part of a general inspection schedule in order to review safety policies and records and to inspect manufacturing equipment. After inspection, a closing meeting is held between the inspector and company health and safety representative to discuss any potential OSH Act violations.

Enforcement

Based on the inspection, a citation may be issued for any OSH Act violations. These citations must be posted in a prominent location in the facilities for at least 3 days. De Minimus violations are not considered serious enough to threaten employee safety and health. Serious violations present a real potential for employee harm and may involve penalties of up to $7,000. Willful or repeated violations carry penalties of up to $70,000 per violation.

Clean Air Act (CAA) Of 1970

The Clean Air Act is actually an amendment of an earlier law (the 1955 Air Pollution Act had weak regulatory provisions) and has been amended eight times, most notably in 1977 and 1990. The CAA is intended to control the discharge of air pollution by establishing uniform ambient air quality standards that are in some instances health-based and in others, technology-based. Mobile and stationary sources of air pollution must comply with source-specific emission limits that are intended to meet these ambient air quality standards. In addition, the CAA addresses specific air pollution problems such as hazardous air pollutants, stratospheric ozone depletion, and acid rain. The 1990 amendments of the CAA revised the hazardous air pollutant regulatory program, instituted a market-based emissions trading system for sulfur dioxide, created strict tail-pipe emission standards for the most polluted urban areas, created a market for reformulated and alternative fuels, and instituted a comprehensive state-run operating permit program.

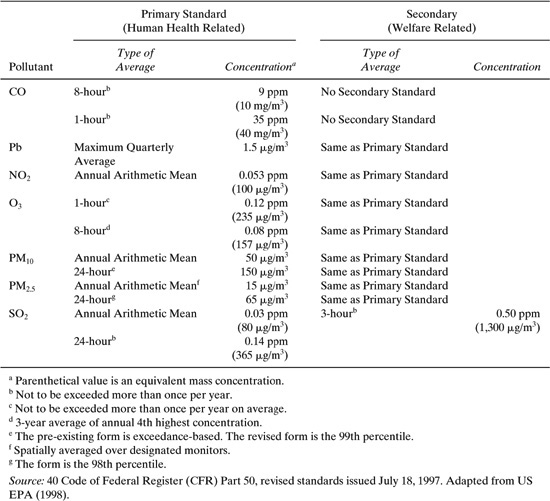

One of the most important steps in achieving the goals of the CAA was the establishment of the national ambient air quality standards (NAAQS). These are maximum allowable concentrations of specific chemicals monitored in the ambient, or background, air that meet or exceed health-based criteria. Table A.3-1 is a list of the primary and secondary NAAQS for the criteria pollutants, carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide, tropospheric ozone, particulate matter, and sulfur dioxide. The NAAQS primary standards are human health-related while the secondary standards are intended to protect a broader range of environmental harm (soils, crops, vegetation, and wildlife); thus they are more restrictive than primary standards.

State Implementation Plan

The CAA requires states to develop individualized state implementation plans (SIPs) that outline how they intend to achieve national ambient air quality standards (NAAQS). The SIP-NAAQS system is an example of “cooperative federalism.” The federal government ensures that the provisions of the CAA are implemented but states are responsible for controlling local sources of air pollution. Thus, the state regulatory agencies establish source-specific emission limits on mobile and stationary sources at a sufficient level to ensure compliance with federal quality standards. Under the CAA, EPA establishes the NAAQS, reviews state-authored SIPs to ensure that they will achieve the NAAQS, and may take over state programs if they fail to implement the SIP effectively.

New Source Performance Standards

The CAA allows emission limits to be set on new sources that are more restrictive than limits on existing sources. These standards are termed New Source Performance Standards (NSPS). The reasoning behind this standard is that controls can be incorporated more easily into new processes than they can be retrofitted into existing processes. EPA established which categories of industrial sources can be subject to these standards, and the emission limits are set by considering the best available emission control technologies, other health and environmental impacts that may occur during the application of the control technology, and energy usage issues. Because the new source standards are uniformly established nationwide, they create a level playing field where companies are discouraged from locating in states that do not require these strict pollution controls.

Table A.3-1 Criteria Pollutants and the National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

Source: 40 Code of Federal Register (CFR) Part 50, revised standards issued July 18, 1997. Adapted from US EPA (1998).

A New Source Review program has been established by the CAA in order to review new processes and significant modifications to existing processes and to prevent significant deterioration of ambient air quality. Before construction can begin, the operator must obtain a permit and demonstrate 1) that the source will comply with ambient air quality standards, 2) that the source will utilize the best available control technology, 3) that their emissions will not cause a violation of the NAAQS in nearby areas, and 4) that new or modified sources must achieve offsets, that is reductions in emissions of the same pollutant, in a greater than 1:1 ratio.

Hazardous Air Pollutants

The CAA has identified 189 hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) that are subject to more stringent emission controls than the six criteria air pollutants. Any stationary source that emits 10 tons per year of any HAP or 25 tons per year of any combination of HAPs is subject to these CAA provisions. EPA is required to develop source-specific emission standards that require installation of technologies that will result in the maximum achievable degree of control (MACT). If an existing source can demonstrate that it has achieved or will achieve a reduction of 99 percent of hazardous air pollution emissions before enactment of the MACT standards, it may receive a six-year extension of its compliance deadline.

Enforcement

Civil penalties for violations of the Clean Air Act may involve fines of up to $25,000 per day of violation. Penalties for knowing violations of the CAA are up to $250,000 per day in fines and up to 5 years imprisonment. Corporations may be fined up to $500,000 per violation and repeat offenders may receive double fines. Knowing violations that involve releases of HAPs may trigger fines of up to $250,000 per day and up to 15 years imprisonment. Corporations may be fined $1,000,000.

The Clean Water Act (CWA) OF 1972

The Clean Water Act (CWA) was first enacted in October 18, 1972 and is the first comprehensive federal program designed to reduce pollutant discharges into the nation’s waterways (“zero discharge” goal). Another goal of the CWA is to make water bodies safe for swimming, fishing, and other forms of recreation (“swimmable” goal). This act has resulted in significant improvements in the quality of the nation’s waterways since its enactment. The CWA defines a pollutant rather broadly, as “dredged spoil, solid waste, incinerator residue, sewage, garbage, sewage sludge, munitions, chemical wastes, biological materials, radioactive materials, heat, wrecked or discarded equipment, rock, sand, cellar dirt and industrial, municipal, and agricultural waste discharged into water” (CWA §502(14), 33 U.S.C.A. §1362). The CWA has two major components, the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit program and the Publicly Owned Treatment Works (POTW) construction program.

Publicly Owned Treatment Works (POTW) Construction Program

This program originally provided grants to POTW so that they could upgrade their facilities from primary to secondary treatment. Primary treatment involves removing a portion of the suspended solids and organic matter using operations such as screening and sedimentation. Secondary treatment removes residual organic matter using microorganisms in large mixed basins. Federal grants, having no repayment obligations, were available for as much as 55% of the total project costs. The 1987 amendments converted the grant program into a revolving loan program in which municipalities can obtain low interest loans that must be repaid.

National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Permit Program

The statute classifies water pollution sources as point sources and nonpoint sources. Point sources are any discrete conveyance (pipe or ditch) that introduces pollutants into a water body. Point sources are further divided into municipal (from POTWs) and industrial. An example of a nonpoint source is runoff from agricultural lands. Nonpoint sources are the last major source of uncontrolled pollution discharge into waterways. The National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit program requires any point source of pollution to obtain a permit. The NPDES permit program is another example of a cooperative federal-state regulatory program. The federal government established national standards (e.g., effluent guidelines), and the states are given flexibility in achieving these standards. NPDES permits contain effluent limits, either requiring the installation of specific pollutant treatment technologies or adherence to specified numerical discharge limits. In establishing the NPDES limits, the state regulatory agency considers the federal effluent guidelines and the desired water quality standards established by the state for the intended use of the waterway (drinking water source, recreation, agricultural, etc.).

Monitoring/Inspection Requirements

NPDES permit holders must monitor discharges, collect data, and keep records of the pollutant levels of their effluents. These records must be submitted to the agency that granted the NPDES permit to ensure that the point source is not exceeding the effluent discharge limits. The permitting agency is authorized to inspect the permit holder’s records and collect effluent samples to verify compliance with the CWA.

Industrial Pretreatment Standards

Industrial sources that discharge into sewers that eventually enter POTWs are termed “indirect discharge” sources. These sources do not need to obtain a NPDES permit, but may have to apply for state or local permits and must comply with EPA pretreatment standards. Pretreatment standards reflect the best available control technology (BACT) and are designed to remove the most toxic pollutants and to minimize the “pass through” of these components into receiving waters from POTWs. Indirect dischargers can obtain removal credits if they can demonstrate that the POTW can effectively remove a particular pollutant down to acceptable levels.

Dredge and Fill Permits and Discharge of Oil or Hazardous Substances

A permit must be obtained from the United States Army Corp of Engineers before any discharge of dredge or fill materials into navigable waterways, including wetlands, occurs. The CWA also prohibits discharge of oil or hazardous substances into any navigable waters and provides mechanisms for the clean up of oil and hazardous substance spills. Any person in charge of a vessel or facility must notify the Coast Guard’s National Response Center and also state officials whenever such a spill occurs above a certain quantity. Failure to do so may result in up to 5 years imprisonment.

Enforcement

Civil penalties may be as high as $25,000 per day for violations of the CWA provisions. Criminal violations for repeated negligent conduct may be as high as $50,000 per day and up to 2 years imprisonment. Repeated knowing violations can result in fines of up to $100,000 per day and 6 years imprisonment. Repeated knowing endangerment violations of the CWA can bring fines as high as $500,000 and 15 years imprisonment. Organizations can be fined as much as $1,000,000. Violations that involve false monitoring and reporting are subject to a $10,000 fine and up to 2 years imprisonment.

Resource Conservation And Recovery Act (RCRA) Of 1976

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act was enacted to regulate the disposal of both non-hazardous and hazardous solid wastes to land, encourage recycling, and promote the development of alternative energy sources based on solid waste materials. In reality, RCRA also regulates any waste material that is disposed to land, including liquids, gases, and mixtures of liquids with solids and gases with solids. RCRA’s Subtitle C provisions regarding the management and disposal of hazardous wastes have become the key provisions. RCRA was significantly amended by the Hazardous and Solid Waste Amendments (HSWA) in 1984. The provisions of the HSWA affect hazardous waste disposal facilities by restricting the disposal of hazardous waste and regulating underground storage tanks containing hazardous substances or petroleum. RCRA’s Subtitle C establishes provisions that must be complied with by hazardous waste generators, transporters of hazardous waste, and facilities that treat, store, or dispose of hazardous waste. RCRA represents a “cradle-to-grave” regulatory system that manages hazardous waste throughout its life cycle in order to minimize the risks that these wastes pose to the environment and to human health.

Identification/Listing of Hazardous Waste

If wastes exhibit any of four hazardous characteristics (ignitibility, corrosivity, reactivity, or toxicity), they are considered to be hazardous. A material can also be designated as a hazardous waste if EPA lists it as such. Three hazardous waste lists have been compiled by EPA. The first list contains approximately 500 wastes from non-specific sources and includes specific chemicals. The second list of hazardous wastes is from specific industry sources, for example hazardous wastes from the petroleum refining industry. The third list includes wastes from commercial chemical products, which when discarded or spilled, must be managed as hazardous wastes. Specifically exempted from being hazardous wastes are household waste, agricultural wastes that are returned to the ground as fertilizer, and wastes from the extraction, beneficiation, and processing of ores and minerals, including coal.

Generator Requirements

EPA defines a generator as any facility that causes the generation of a waste that is listed as a hazardous waste under RCRA provisions. A generator of hazardous waste must obtain an EPA identification number within 90 days of the initial generation of the waste. RCRA requires generators to properly package hazardous waste for shipment off-site and to use approved labeling and shipping containers. Generators must maintain records of the quantity of hazardous waste generated and where the waste was sent for treatment, storage, or disposal, and must file this data in biennial reports to the EPA. Generators must prepare a Uniform Hazardous Waste Manifest, which is a shipping document that must accompany the waste at all times. A copy of the manifest is sent back to the generator by the treatment facility to ensure that the waste reached its proper destination.

Other Requirements

RCRA imposes requirements on transporters of hazardous waste as well as on facilities that treat, store, and dispose of hazardous wastes. Transporters are any persons that transport hazardous waste by air, rail, highway, or water from the point of generation to the final destination of treatment, storage, or disposal. The final destinations are termed treatment, storage, and disposal facilities (TSDFs) by EPA. Transporters must adhere to the Uniform Hazardous Waste Manifest system when shipping hazardous waste, which includes retaining copies of manifests for a period of three years. A facility that accepts hazardous waste for the purpose of changing the physical, chemical, or biological character of the waste and with the intent of rendering the waste nonhazardous, making the waste amenable for transport or recovery, or reducing the waste volume is defined as a treatment facility by RCRA. Storage facilities are intended for holding wastes for a short period of time until such time as the waste is shipped to a treatment or disposal facility elsewhere. A disposal facility is a location that is engineered to safely accept hazardous waste in various forms (drums, solids, etc.) for long term internment. These facilities must monitor the environment within and adjacent to the facility to assure that hazardous waste components are not leaving the site in concentrations that threaten the environment or human health. Generators who store hazardous waste on site for more than 90 days or who treat or dispose of hazardous waste themselves are considered TSDFs by RCRA.

Enforcement

Failure to comply with RCRA Subtitle C or EPA compliance orders carries a civil penalty of up to $25,000 per day of violation. Violations may result in the revocation of the RCRA permit. Criminal penalties for violations may be as high as $50,000 per day for each violation and/or 2 years imprisonment. Fines and jail time may double for repeat offenders. When a person violates RCRA and in the process knowingly endangers another individual, fines may reach $250,000 per day and up to 15 years imprisonment. Organizations may be fined as much as $1,000,000.

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, And Liability Act (CERCLA) Of 1980

The contamination of Love Canal in upstate New York with industrial toxic materials and the subsequent evacuation of hundreds of families from the vicinity, alerted the federal government of the need to clean up this and other related sites. The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980 began a process of identifying and cleaning up the many sites of uncontrolled hazardous waste disposal at abandoned sites, at industrial complexes, and at federal facilities. EPA is responsible for creating a list of the most hazardous sites of contamination, which is termed the National Priority List (NPL). As of 1994, there were 1,232 facilities, including 150 federal facilities, on the NPL and an additional 340 to 370 sites are expected to be added to the NPL before September 30, 1999. CERCLA established a $1.6 billion Hazardous Substance Trust Fund (Superfund) to initiate cleanup of the most contaminated sites. Superfund (the trust fund) allows for the cleanup of sites for which parties responsible for creating the contamination cannot be identified because of bad record keeping in the past, or are no longer able to pay, are bankrupt, or are no longer in business. The Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA) of 1986 increased the Superfund appropriation to $8.5 billion through December 31, 1991, extended and expanded the tax for Superfund, and stipulated a preference for remedial action to be cleanup rather than containment of hazardous waste. In addition, Superfund was extended to September 30, 1994 with an additional $5.1 billion. As of this printing, the Superfund program continues to operate via yearly US EPA budget appropriations, fund interest, and cost recoveries from PRPs (see below), though no new appropriations have been added to the trust fund since 1995. Under the CERCLA provisions, EPA can make two responses to sites of hazardous waste contamination. These are short-term emergency response to spills or other releases, and long-term remedial actions, which may actually occur long after the site is listed on the NPL, and which is designed to achieve a permanent state of cleanup.

Potentially Responsible Party (PRP) Liability

After a site is listed in the NPL, EPA identifies potentially responsible parties (PRPs) and notifies them of their potential CERCLA liability. If the cleanup is conducted by the EPA, the PRPs are responsible for paying their share of the cleanup costs. If the cleanup has not begun, PRPs can be ordered to complete the cleanup of the site. PRPs are 1) present or 2) past owners of hazardous waste disposal facilities, 3) generators of hazardous waste who arrange for treatment or disposal at any facility, and 4) transporters of hazardous waste to any disposal facility. Liability for PRPs is strict, meaning that liability can be imposed regardless of fault or negligence. Liability is joint and several, meaning that one party can be held responsible for the actions of others when the harm is indivisible. Finally, the liability is retroactive, meaning that parties can be held liable for actions that predate CERCLA. The EPA does not have to prove that a particular PRP’s waste caused the contamination. EPA only has to prove that there are hazardous substances present at the site that are similar to those associated with a party’s hazardous waste treatment and disposal activities.

Enforcement

EPA can force PRPs to conduct and fund cleanup of contaminated sites to which they have been associated in actions termed Private Party Cleanups. Failure to comply with a Private Party Cleanup order may involve fines of up to $25,000 per day and judicial reviews of these cases are not immediately available. Thus, PRPs have little choice but to comply. Failure to report to EPA the release of hazardous substances in quantities greater than the cut-off value for that substance may result in fines amounting to more than $25,000 per day and criminal penalties of three years for a first conviction and five years for a subsequent conviction.

The Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act (EPCRA)

In 1984, the release of methyl isocyanate from a Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India killed more than 2,500 people and permanently disabled some 50,000 more. This unfortunate incident illustrated the need for communities to develop emergency plans in preparation for releases that might occur from chemical manufacturing facilities. It also highlighted the need for communities to find out what toxic chemicals are being manufactured at facilities and what are the rates and to what media toxic chemicals are being released. Title III of the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA) contains a separate piece of legislation called the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA). There are two main goals of EPCRA: 1) to have states create local emergency units that must develop plans to respond to chemical release emergencies, and 2) to require EPA to compile an inventory of toxic chemical releases to the air, water, and soil from manufacturing facilities, and to disclose this inventory to the public.

Toxic Release Inventory (TRI)

EPCRA requires facilities with more than 10 employees who either use more than 10,000 pounds or manufacture or process more than 25,000 pounds of one of the listed chemicals or categories of chemicals to report annually to EPA. The report must contain data on the maximum amount of the toxic substance on-site in the previous year, the treatment and disposal methods used, and the amounts released to the environment or transferred off-site for treatment and/or disposal. Facilities that are obligated to report must use the Chemical Release Inventory Reporting Form (Form R). Facilities must keep records supporting their TRI submissions for three years from the date of submission of Form R to EPA. The data are compiled by the EPA and entered into a computerized database that is accessible to the public. The TRI is viewed by citizens, environmental groups, states, industry, and others as an environmental scorecard for the chemical manufacturing and allied products industries. As a result of the TRI, many manufacturers have initiated voluntary programs to reduce the releases of toxic chemicals into the environment. In 1990, the EPA implemented the 33/50 Program, a voluntary program for participating facilities to reduce their releases of 17 key chemicals by 33% by 1992 and 50% by 1995 compared to baseline levels. As of October 1999, 1294 companies had committed to the program (EPA, 1999).

Enforcement

Violations of EPCRA’s TRI reporting and community emergency planning requirements are subject to civil penalties of up to $25,000 per day. Any person who knowingly and willingly fails to report releases of toxic substances can be fined up to $25,000 and/or be imprisoned for up to 2 years. Second violations may subject persons to fines of up to $50,000 or 5 years imprisonment.

Pollution Prevention Act Of 1990

In October 27, 1990, the Pollution Prevention Act was passed by Congress. The act established pollution prevention as the nation’s primary pollution management strategy. Pollution prevention is defined as “any practice which: 1) reduces the amount of any hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant entering any waste stream or otherwise released into the environment… prior to recycling, treatment, and disposal; and 2) reduces the hazards to public health and the environment associated with the release of such substances, pollutants, or contaminants.” Thus, pollution prevention not only encourages reductions in waste generation and release from production facilities but also promotes reductions in waste component toxicity or other hazardous characteristics. This strategy is fundamentally different from those of prior environmental statutes, in that pollution prevention encourages steps to reduce pollution generation and toxicity at the source rather than relying on end-of-pipe pollution controls.

The Pollution Prevention Act (PPA) provides for a hierarchy of pollution management approaches. It states that: 1) pollution should be prevented or reduced at the source whenever feasible, 2) pollution that cannot be prevented or reduced should be recycled, 3) pollution that cannot be prevented or reduced or recycled should be treated, and 4) disposal or other releases into the environment should be employed only as a last resort. The Act is not an action-forcing statute, but rather encourages voluntary compliance by industry of the suggested approaches and strategies through education and training. To this end, EPA is required to establish a Pollution Prevention Office independent of the other media-specific pollution control programs. It is also required to set up a Pollution Prevention Information Clearinghouse whose goal is to compile source reduction information and make it available to the public. The only mandatory provisions of the PPA requires owners and operators of facilities that are required to file a form R under the SARA Title III (the TRI) to report to the EPA information regarding the source reduction and recycling efforts that the facility has undertaken during the previous year.