KSAM as an organizational change: making the transition

Abstract

Once convinced of the efficacy of KSAM, companies need to consider how to achieve the vision that academics have painted for them, but the literature has very little to say about how to make the change. Success is not guaranteed. This paper looks at the journey to best practice KSAM and identifies early and later phases of activity that mark the development of the organization as a KSAM operator. The different elements and actions that comprise these phases are determined in terms of strategy and planning, organization and culture, and processes.

Introduction

Academic literature is largely focused on the very important need to paint the picture of how key strategic account management (KSAM) should look or does look. However, as increasing numbers of companies have ceased to challenge the KSAM vision and accepted the concept, their attention has shifted to issues of implementation and particularly how the transition can be achieved. Research has concentrated on inter-organizational relationships (e.g. Ford 1980; Gosman and Kelly 2000; Ivens and Pardo 2007; Millman and Wilson 1995) rather more than intra-organizational structures and adaptations for managing them (Kempeners and van der Hart 1999; Zupancic 2008).

Indeed, KSAM failure is not uncommon (Napolitano 1997; Wilson and Woodburn 2014) and companies are understandably anxious to avoid it, although academics may be more interested in examining the issue of why failure is so common (Wilson and Woodburn 2014). While this paper is concerned with exploring how transitioning towards best practice is achieved, there is more than a suspicion that many failures may be because the company never actually made the transition to KSAM. Homburg et al. (2002) identified several forms of KSAM, some of which are not KSAM at all (‘Country club KSAM’) or are so inefficient that they barely qualify, i.e. ‘Middle management’ KSAM, ‘Operating level’ KSAM, ‘Unstructured’ KSAM, ‘Isolated’ KSAM.

In 2005/2006 a group of global and national companies at different stages in their KSAM development together charted the various actions they had completed to establish KSAM in their organizations (Woodburn 2006). Much of the material in this paper was discovered and developed through that project, particularly the KSAM transitioning journey, which mapped out the actions and changes that each phase of development had demanded. The findings and model of KSAM development in Woodburn (2006) were later corroborated by quantitative research in Davies and Ryals (2009).

This project soon made it clear that establishing KSAM is a journey which is not completed quickly (Capon and Senn 2010; Wengler et al. 2006; Woodburn 2006): indeed, it may be seen as an extended and possibly never-ending journey, as suppliers are obliged to continually develop the ways they work with their key customers. Progress post-introduction is rarely linear, and can go backwards as well as forwards (Capon and Senn 2010), so continuous improvement cannot be assumed: constant pressure is needed to maintain forward momentum. Indeed, whatever has already been done to develop KSAM, there is more yet to do because, as it develops, it touches more people and processes in the supplier company and in the customer too.

Companies normally find change difficult, and suppliers often underestimate the time, effort and investment needed to achieve KSAM success. It is a major organizational change, not just the latest sales initiative (Capon and Senn 2010). Underestimating the scale of the change is likely to mean that the development process is set unrealistic deadlines, is under-resourced, is unsupported by senior management across the board and ultimately fails against impracticable short-term expectations.

KSAM strategy

Strategy should, of course, lead any organizational change, although observation suggests that it is often not the case, and existing structures, culture and objectives often override the optimum expression of the strategy. KSAM is an organizational change, though suppliers frequently do not recognize it as such and make the mistake of underestimating what is required to achieve what they seek.

Introducing KSAM is itself a strategy, but like any strategy, it requires further expression before it becomes a direction that people can understand, align with and implement. While KSAM is itself focused on the interface with key customers, it needs to be related to other company strategies in order to be effective and to deliver the promised value to key customers (see ‘KSAM structure’ on page 83). Strategies from supply chain, product development, customer service through to marketing, finance and human resources should all take account of KSAM demands, and need to be aligned accordingly.

KSAM strategy is implemented at both a programme level – developments in organization, recruitment, resources, processes, etc. – and the level of individual key accounts. The strategies formulated for customers will specify what value is appropriate for each of them, and will therefore collectively define what operational strategies the supplier needs to adopt to fulfil those promises. Companies may realize the modifications they need in KSAM-linked strategies top-down, by developing the programme at a high level, or bottom-up, through collating their strategic account plans (see Woodburn 2006), which gives them a more concrete view of the changes required, or probably a combination of both. Whatever the process applied, the reformulation of all functional strategies to align them around KSAM at the time of its introduction should not be overlooked or delayed.

A strong, even painful stimulus often launches a company's desire to introduce KSAM. Identifying the stimulus is useful in demonstrating the need for change: it helps enormously if the whole organization knows what the driver(s) is and can appreciate why the company has to change. Not only does everyone then understand the importance or even necessity of the initiative, but they are more likely to identify appropriate responses to the company's specific drivers.

Drivers of KSAM

Organizations rarely make the effort to adopt KSAM unless there is a powerful driver behind it, often triggered by a particular issue or event. An event may be a symptom of an underlying trend or need that has not gained credibility or urgency until the event drew attention to it, such as the loss of a major customer because of the inflexibility of the supplier's approach, or a punitive drop in profit owing to mistakes made through poor coordination. The ‘tipping point’ for action is often provided by negative stimuli such as the loss of a major contract, a public brawl between companies or other adverse publicity, or unexpectedly or persistently bad results.

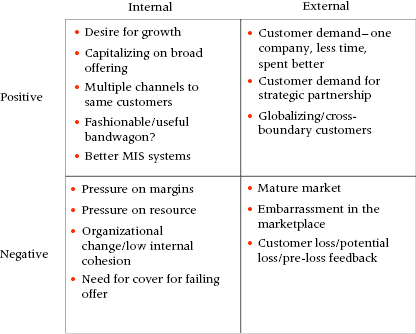

However, drivers for KSAM can be positive as well as negative, and may originate from inside or outside the organization. Negative external drivers are powerful, but there are also positive drivers that may be leveraged to promote the initiative or to make it possible – see Figure 1. Organizations often contain a potential champion for KSAM (McDonald et al. 2000) who has observed an opportunity or an alarming trend and is convinced that KSAM is the route to dealing with it. Champions who have not yet gained the attention and support of the company to take action may use untoward events and wield them as ‘sharp sticks’ to goad their companies into action.

Figure 1 Drivers of KSAM

External drivers

Customers have wanted KSAM treatment from their suppliers for a long time (Yip and Madsen 1996; Woodburn and McDonald 2001); indeed, KSAM is basically a customer-driven approach so, unsurprisingly, a large part of the external drivers originate with customers. Responding to them may be seen as positive, while the fear of actually losing a key account is certainly negative, as is embarrassment in the marketplace arising from, for example, poor coordination or opportunism made visible. In a mature market, products become commoditized and price pressures more severe, leaving KSAM as one of the few differentiators still available.

Internal drivers

Where key accounts are a substantial amount of a company's profits, the supplier may see that the best growth opportunity lies with those customers, especially as they tend to be market leaders growing at a greater rate than their competitors. KSAM then potentially becomes the main contributor to the supplier's ambition. Furthermore, where the supplier has a wide offering across a range of routes to market, it can gain synergy and cut waste and confusion through coordinating its offer, and that coordination needs KSAM for its delivery. Better management information systems (MIS) provide the mechanics for coordination and information supply, which makes effective KSAM more possible now than in the past.

Negative internal drivers, such as pressure on margins and resources, may drive companies to deal with them through KSAM, but they pose problems for the initiative too: KSAM is not a cost-saving solution, although longer term it should provide a good return, albeit not guaranteed (Kalwani and Narayandas 1995; Reinartz and Kumar 2002). Some companies have tried to compensate for a failing offer or service through KSAM (‘putting lipstick on the pig’) but it is unlikely to succeed in such circumstances and is not recommended until the underlying issues have been fixed.

Often at the outset KSAM champions emerge who will identify the most powerful drivers and decide how they can best be employed. However, even if there are clear reasons for change, there will also be strong resistance from internal forces: from people who simply do not like change, or who consider any new approach to be a criticism of what they have done to date, or who see the new way of working as eroding their territory or power base. The company needs to be constantly reminded of the compelling reason why it opted for KSAM, as the champion inevitably meets resistance.

Customer demand for KSAM treatment is a strong driver (Buzzell 1985), but some suppliers still fail to recognize it (or prefer not to). Indications that customers are either consciously seeking KSAM or are unconsciously ready for it include customers who are:

- Communicating opportunities and initiatives and involving the supplier in their strategies.

- Expecting an understanding of their business: inviting the supplier to meet a wider range of people in their organization and giving a broad range of information about their business and marketplace.

- Wanting to explore joint projects involving more commitment.

- Wanting to talk longer term and develop strategies together.

- Asking for a more senior account manager with more authority and/or competency.

- Wanting a transparent or integrated approach and a single point of contact, dealing with them as a single entity.

This list can be turned into a simple ‘litmus’ test, which can quickly show whether the supplier has customers who are ready for KSAM. Not all of the indicators in the list need to be positive to make the case for KSAM: any one of them could be sufficient. Furthermore, it is clearly not necessary for all of a supplier's customers to want KSAM in order to instigate a programme – many do not qualify anyway, nor is there any point in forcing it on those who do not want it. The crucial question is whether a significant amount of the business is tied in with customers who do want KSAM treatment and will respond to it.

KSAM strategy implementation

A wide range of KSAM success factors has been studied (e.g. Stevenson 1981; Workman et al. 2003; Wotruba and Castleberry 1993; Zupancic, 2008), mostly focusing on specific elements of programmes that have proved successful, assuming that, once identified, companies can adopt these elements. And yet KSAM failure is all too common. Studying the failure factors can help to illuminate the success factors. Natti and Ojasalo (2008) found four barriers to the utilization of customer knowledge originating in the supplier organization, while Wilson and Woodburn (2014) also found that less tangible elements relating to culture and norms were more often cited as causes of failure than were the formal elements of KSAM, which can be written down and documented. In fact, Workman et al. (2003) found that KAM formalization was negatively correlated with KAM effectiveness.

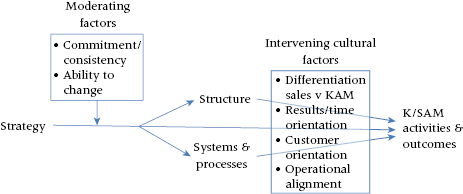

Problems were less about whether the KSAM strategy was clear or appropriate (though a lack of clarity was also mentioned) and more about whether the company as a whole was really committed to it and could apply that commitment consistently. Challenges to companies' capability of changing at all were also common. These were called moderating factors, which undermine and compromise the KSAM initiative from the outset. Also collected were a number of intervening cultural factors, which indirectly but effectively obstruct the implementation of KSAM. Figure 2 depicts a model of KSAM-relevant organizational elements, showing both of these types of factor.

Figure 2 A model of the linkages between organizational elements in KSAM (Wilson and Woodburn 2014)

This model suggests that companies should change their behaviour very visibly, communicate the strategy and the change in their expectations clearly and with conviction and consistency (across the organization and across time), and instigate a process of change that will prevent recidivism. If, in reality, there is very little change activity, coupled with ambivalence about moving to KSAM, the people concerned will reflect that inertia and ambivalence and either be slow to respond, while they wait to be convinced that the company is serious about KSAM, or not change at all.

However, the model suggests a further set of failure factors which can also frustrate KSAM strategy, even if the strategy has clear and consistent commitment: those emanating from the culture. For example, Workman et al. (2003) found that ‘it is not so much the extent of team use that matters but rather the development of an organizational culture that is committed to supporting KAM’. In Wilson and Woodburn (2014) negative cultural aspects included a lack of differentiation between sales and KSAM, over-strong focus on results in the short term, a lack of genuine customer orientation and a lack of alignment with KSAM in the operational functions. These issues also require conscious action to change them both initially and on a continuing basis. Without continued focus and effort, companies easily slide back to their pre-existing orientation and ways of working, some of which are destructive to the KSAM strategy.

KSAM structure

All structures in companies of any size carry with them intrinsically anti-KSAM features, so companies have to choose the structure that seems the least unhelpful, rather than an ideal. Indeed, organizational structure in KSAM poses a conundrum: key customers expect to be influential and therefore close to the supplier's senior management (which implies that the key account manager should be in such a position). At the same time, they expect prompt and consistent delivery of value, which suppliers feel requires the key account manager's proximity to operations – they are concerned that key account managers may become divorced from reality at ground level (Woodburn 2006). Many-layered structures in which the position of the customer representation (i.e. key account manager) is structurally distant from senior managers are not welcome to key customers and may be read, not unreasonably, as indicative of their true importance to the supplier.

Positioning KSAM in the organizational structure

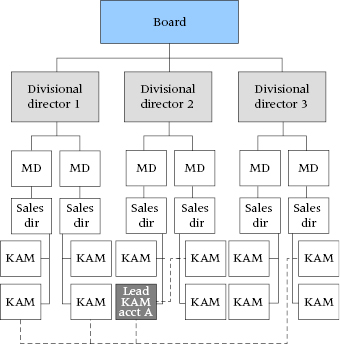

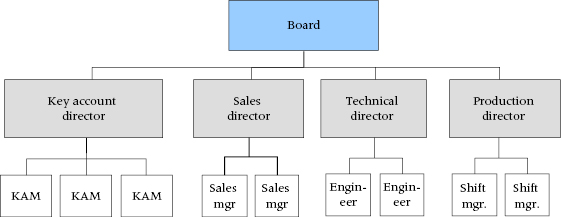

Difficulty in devising an ideal structure does not mean that all structures are equally good for KSAM: there are forms of organization that make KSAM particularly difficult. The (very common) multi-level hierarchy shown in Figure 3 is not popular with key customers, who see the key account manager in this kind of structure as having very low levels of seniority, influence and decision-making power, which is probably true. Normally, each key account manager is not empowered to speak for other divisions in the company from which the customer might also purchase, and has to refer discussions to other key account managers, but to achieve better coordination and satisfy the customer's desire for ‘single point of contact’ while avoiding structural change, some companies nominate a ‘lead key account manager’, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Adding ‘lead’ key account managers in a multi-level hierarchy

The ‘lead’ is normally positioned in the division that already does most business with the customer because the existing relationship is seen as a deciding factor. The figure shows an example of one lead key account manager but in reality there would be at least several more working with other key accounts, and then the picture becomes complex and difficult to manage. Key account managers in such situations generally have limited empowerment and are trying to operate a difficult model from a relatively weak position.

While this least-disturbance approach is popular with supplier management, the majority of companies struggle to make this model work well enough to meet the expectations of key customers – see Table 1.

Table 1: Advantages and disadvantages of lead key account managers

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Improves communication and coordination | Does not deliver genuine integration, sub-optimal for customers |

| Keeps key account managers close to delivery, keeps them ‘real’ | Key account manager promotes home business more strongly: works in comfort zone, responds to ‘home’ senior management |

| Does not disturb current structure in the rest of the company | Not good for growing new business from other divisions, maintains status quo |

| Aligned with current role and competencies of key account managers | Limited empowerment, hard to operate, involves constant, difficult internal negotiations |

| Flexible | Complicated, difficult for others to understand and work with |

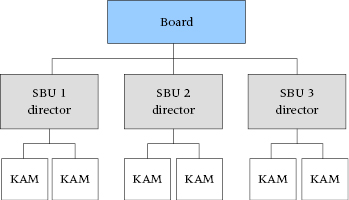

The critical issue is the key account managers' degree of empowerment, especially outside their ‘home’ organization. Elevating the key account managers in the hierarchy or flattening the structure helps, as in Figure 4, but internal divisional or geographical boundaries, normally strengthened by financial targets, will give rise to most of the same problems. These matter when the most important customers interact with more than one supplier-defined strategic business unit (SBU).

Figure 4 Regional structure with more senior key account managers

To overcome the shortcomings of the preceding structures, some suppliers have introduced high-level KSAM units where key account managers operate at only one level removed from the board and their line manager sits on the board – see Figure 5. This structure is designed to minimize internal competition and reduce the distance between the board and the key account manager representing the customer, but strong, clear links need to be made with the operational delivery functions in the company to enable it to work as it should, without introducing new internal boundaries. Companies with a single product division operating in one country with national key accounts can organize themselves in this way more easily than multi-nationals and multi-product companies.

Figure 5 High-level KSAM structure

Ultimately, strict hierarchies are not conducive to the flexibility required for KSAM, leading suppliers towards a matrix structure, preferably with two dimensions reflecting both product/service and customer requirements. Most companies need to operate with a strong structure around their products/services, in order to achieve and maintain excellence in what they offer. For a similar reason, to maintain excellence in how they offer it, they also need a strong structure around their customers, particularly their key customers. When suppliers operate a third axis as well (normally geography), one or two axes generally emerge as stronger and it often appears to be the customer dimension that is weakest (Woodburn et al. 2004).

Because the key account manager needs to pull activities together across the company, any structure will have its shortcomings. Companies accustomed to working in a matrix structure are likely to find the change easier than traditionally hierarchical companies in which attitudes and habits will need substantial recasting. Ideally, the organization should be flexible enough to mirror the customer's organization, but companies struggle with managing the complexity and general untidiness of such a variable approach.

Change in organizational structure is not sufficient on its own: it is supported or defeated by formal and informal networks, systems and processes, objectives and targets and also by attitudes and cultural norms. All need to be addressed at an early stage to achieve a successful transition (for a case study in change, see Guenzi et al. 2009).

Positioning KSAM and sales

A lack of understanding of the nature and purpose of KSAM, and therefore a lack of differentiation between sales and KSAM, leads to inappropriate decisions on its positioning in the organization (Wilson and Woodburn 2014). Key account managers cited the conflict between the ‘opposing philosophies of traditional sales and account management’ as a cause of KSAM failure, especially when the management of both sales and account management programmes falls under sales management, who are ‘uneasy with the process’.

Sales directors/managers find it difficult to treat their two types of reports differently and tend to apply familiar, traditional sales management practices, such as short-term sales targets, call number targets and standard resource allocation, which are inappropriate in KSAM. Key accounts require more varied, customer-specific approaches and lower-quantity, higher-value activity. In addition, sales managers often promote traditional territory sales people to the role of key account manager, who are largely moulded by their previous experience in traditional selling. In Wilson and Woodburn (2014), key account managers reported a poor understanding of the role as a common cause of failure. It was ‘perceived as being primarily a sales role rather than a management role’, with key account managers judged on their ability to grow sales rather than nurture customers. Their companies reflected a mentality of ‘it all comes down to sales in the end’.

To achieve the required change, sales directors' attitudes should be addressed, as well as those of key account managers with sales backgrounds. New person and job specifications, together with new recruitment and personal development policies and new terms and conditions, are required: a sales department that has simply been renamed is likely to revert to selling behaviour, as Woodburn (2006) found. Factors originating in both the organization's sales culture and the key account managers themselves work against the change to KSAM:

- Strong, even relentless, focus in the business on current sales results.

- Reward systems designed for sales (Ryals and Rogers 2006; Woodburn 2008).

- Salespeople like it (they feel successful when they close a deal).

- Security and familiarity (‘we know how this works’).

- Confidence in outcomes (clearer cause and effect linkages).

The way in which key account managers spend their time is a key indicator of KSAM development progress. Woodburn (2006) found that companies operating KSAM believed that only 5–10% of a key account manager's time should be spent on selling (when defined as converting specific opportunities to wins, i.e. managing the sales cycle, gaining bid sign-offs, pitching and closing the deal). While selling is clearly an important element of the key account manager's role, it is one among others. Table 2 shows how supplier KSAM programme managers thought key account managers' time should be allocated, alongside how they feared their people were currently deploying their time.

Table 2: Key account manager's use of time

| Key account manager activity | Actual | Should be |

|---|---|---|

| Developing relationships | 25% | 20% |

| Implementing and motivating the deal operationally | 25–30% | 15% |

| Developing industry knowledge/understanding strategy/planning | 0% | 5–15% |

| Selling/achieving sales result, bid. sign-off | 30–50% | 5–10% |

| Internal alignment for deal commercially | 0–15% | 5–10% |

| Internal day-to-day problem solving | 15% | 5% |

| Internal understanding of capability | 0% | 5% |

| Promoting brand/business | 0% | 5% |

| Reporting/providing information | 0–10% | 5% |

| Training and education | 0–5% | 5% |

| Team management | 0% | 5% |

| Other | ? | 10% |

| Total (of mid-points of ranges) | 113% | 100% |

Key account teams

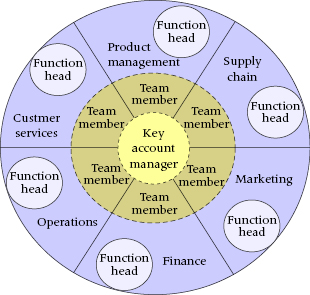

Key account teams have become common in the management of key accounts in companies that have realized the range of activities involved in KSAM. Members are drawn from a variety of functions, depending on the needs of the business with the customer – customer service and technical specialists are frequently members, but marketing, product management and finance are also often included. Members are almost always only partially dedicated to the key account, so in most cases they have ‘dotted line’ reporting to the key account manager and ‘solid line’ reporting to their functional head. Commonly, team members have other key customers with which they work and/or they also have objectives set by their ‘home’ function. As a result, the biggest single issue in the effective operation of key account teams is the cooperation of team members and allocation of their time, given the conflicting demands of their functional head and key account manager(s), as Figure 6 suggests.

Figure 6 Cross-functional key account teams

These teams are tasked with the long-term management of the customer. Team members are a fundamental part of the relationship and are highly valued by the customer, so there should be a consistent core of team members at least. However, functional heads who are the ‘resource owners’ do not always see continuity as an issue and may reallocate members quite casually, overlooking the importance of the relationship with customer staff and the fit with the customer's business.

The dimensions of the following characteristics of key account teams seem to define their ‘atmosphere’, ways of working and success (Atanasova and Senn 2011; Woodburn 2009):

Support for key account teams is critical to their success and that of KSAM as a whole. Because of their relatively informal nature they can be invisible in the organization and membership may be seen as extra work with very little recognition for it. Atanasova and Senn (2011) found that their performance was directly influenced by three team processes: communication and collaboration, conflict management and proactiveness. Where key account teams work well, the supplier organization makes a particular effort to communicate and celebrate their role and efforts in the view of the rest of the company.

Making the change

KSAM is probably difficult to implement because it is a cultural as well as a business initiative. Effective cultural change starts with an exploration of the gap between the current situation and the desired situation and a stage of ‘unfreezing’ (Lewin 1946) to allow people to move on. Successful change programmes demand sensitivity, political awareness, clarity, consistency, translation into practicalities, energy and stamina from the people determined to make the change happen. In some companies a KSAM champion emerges or is appointed, with or without the support of a core team.

A KSAM champion with a high level of seniority in the organization can make a huge difference to success: they can maintain a focus on pushing KSAM through and keeping development on track, not just to kick-start the programme but also to keep up the forward momentum over the next few years. The KSAM champion must convince senior management of the imperative for change and sustain that view over a long period of time and through some tough battles, particularly with the sales force.

Commonly, a large proportion of the sales force, regardless of seniority and sales experience, will lack much of the skill set required to fulfil key account manager positions. Nevertheless, the current sales force and its management generally need to be won over, which may be difficult: KSAM is often seen as challenging the status quo and territorial interests, and indeed it does. Their development should be recognized and training and learning opportunities offered at an early stage, rather than later, still making the requirement to adapt very clear.

There will be others around the organization who are threatened by the change, both in reality and in their imagination, and their issues must be recognized too. Overlaying the corporate culture are national cultures in international companies and all the sub-cultures of functions such as sales, supply chain, service, marketing, etc. Furthermore, underlying the corporate culture in all companies are informal networks and links: the ‘under-culture’. People who currently feel comfortable and in control will have to move to situations that they cannot yet visualize and where, honestly, their control and comfort are likely to be diminished. Others will find their power and influence increased, and some may be uncomfortable with that too. A significant change like KSAM has strong political overtones, both during set-up and in later implementation (Wilson and Millman 2003).

A common vision of what KSAM means for the organization should be created and communicated widely, whereas companies frequently embark on KSAM with vague and various ideas of what is involved, including the widespread belief that it is a sales function initiative whose implications will be limited to sales. Broad senior management support and engagement must be gained for sustainable KSAM (Brady 2004; Wilson and Woodburn 2014) in order to achieve cross-functional support for major change and for serious investment. ‘A firm commitment from senior-level management won't ensure a program's success, but the lack of commitment can seal a program's failure’ (Stevens 2009).

Interestingly, KSAM champions are not always entirely frank with senior management in explaining the extent of change required for successful KSAM (Woodburn 2006). Quite frequently, they describe an intermediate, transition stage of KSAM to senior managers, in order not to alarm them and risk an adverse reaction, unless the CEO or MD is also the KSAM champion.

The KSAM champion or core team will need to:

- Articulate what KSAM is and how it differs from existing approaches.

- Agree KSAM's priority versus other initiatives.

- Specify the effort and supporting action required from senior managers.

Companies can take one of three approaches to the speed and scale of the change: revolution, ‘step-change’ or incremental evolution. Some companies would like to run a pilot programme, but it is debatable whether a valid pilot is possible. Given the inevitable limitations in duration, completion and commitment, the trial will be deficient as a microcosm of eventual reality and may not expose or illuminate important issues, leaving companies not much the wiser about the chances of success or the issues they will meet in a full implementation.

Although incremental evolution is seen as safer, it may not even be noticeable and therefore gets little attention and response, so it stands a greater risk of fizzling out, which is itself a risk. However, few companies seem able to cope with revolution and ‘step-change’ is probably the most common approach. ‘Step-change’ is also advisable where a powerful or urgent driver exists because it creates urgency, gets noticed and highlights the need for action, reaches critical mass and delivers a result, but it will also create ‘problems’. However, if a significant corporate initiative is not creating problems, change is probably stalled.

As Wilson and Woodburn (2014) suggest (see above), in order to be successful through KSAM, and particularly in order not to start and fail, companies should see it as an important corporate change programme and give it the commitment, attention and resources to work.

The KSAM transitioning curve

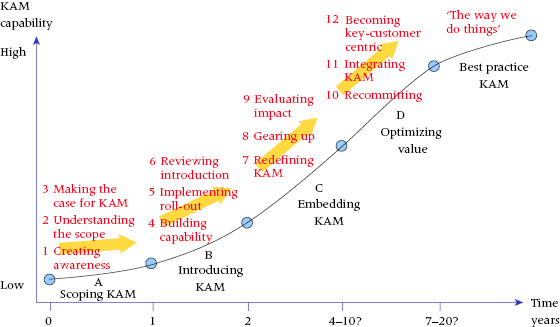

The transitioning curve describing how KSAM development proceeds in most organizations (Woodburn 2006) is shown in Figure 7. The curve is assembled from the actions taken by companies from different sectors in their KSAM development journeys. It represents a fairly realistic picture, neither idealized nor peppered with mistakes, but it does include sub-optimal stages through which most companies pass. Most companies take a wrong turn at some point and head into a cul-de-sac from which they have to extricate themselves, but these individual excursions have been omitted.

Figure 7 Transitioning to KSAM

Normally, KSAM development seems to be organized into five principal phases:

The first four phases are discussed here, but not the last, i.e. arrival at ‘Best practice KSAM’, since that occupies much of the literature. The phases can overlap, as some companies emphasize certain elements more than others and advance faster in those areas. In particular, the early phases, A ‘Scoping KSAM’ and B ‘Introducing KSAM’, may not be cleanly divided into the sequence of action charted (Davies and Ryals 2009), as suppliers sometimes commit themselves to KSAM and start to introduce elements of it before having completed their evaluations. Time to introduction, the end of Phase B, consistently takes about two years, but can take longer. Shorter periods seem rare, so suppliers contemplating introduction need to adjust their expectations accordingly.

The time required for Phases C and D seems less consistent, but 5–10 years is likely even for suppliers steadfast in their determination to make progress. However, Phase C, ‘Embedding KSAM’, often takes that amount of time on its own and many companies get stuck there, never reaching Phase D, ‘Optimizing value’, because deep down they are not ready to take on some of the organizational changes and power shifts involved. Some companies have been implementing KSAM in various forms for 20 years but still could not say they had reached best practice. Capon and Senn (2010) describe slightly different stages, taking potentially even longer, and still best practice is not guaranteed.

Each phase can be divided into three periods or sub-phases, following on from each other approximately chronologically, in which different actions are executed or initiated. There will undoubtedly be considerable overlap between the sub-phases, so any sequence of actions should not be taken as set in stone – in some focus areas action might be quite advanced, while others have been left unattended.

A wide range of action is involved in implementing a KSAM programme. The necessary actions can be grouped into three coherent streams of activity observable across all KSAM phases. Suppliers will, at most times, have some development activities running that address:

- Strategy and planning.

- Organization and culture.

- Processes.

The balance of activity changes across different phases. A heavy focus on strategy and planning would be expected at the outset, with little, if anything, developing in processes at that point. Action addressing process adaptation increases later on, as the focus is rebalanced from strategy towards implementation. Development can be further described as contributory streams of activity within each broad area of the initiative, as shown in Table 3. In addition, at some points there will be critical milestones to pass, such as the point when a company decides whether or not to adopt KSAM, or to recommit to KSAM at a later stage.

Table 3: Activity streams in KSAM development

| Stream of activity | Contributory streams | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Strategy and planning | Goals and strategy | Vision and overall aims |

| Planning and objectives | Specific planning activities and quantified forecasting | |

| Research | Finding out information needed from internal and, importantly, external sources | |

| Organization and people | Key account managers | Changes in the role, rewards and development of and for the individual |

| KSAM teams and the KSAM community | People consistently working on a key account or the KSAM programme | |

| The wider organization and senior management | Addressing the rest of the company | |

| Processes | Key account manager activities | Processes engaging individual key account managers and generally their responsibility |

| Other KSAM activities | Processes involving the KSAM community, typically customer service, monitoring and review | |

| Core processes | Operational processes run by the rest of the organization, not specifically for KSAM |

The early stages

Phase A: Scoping KSAM

This first phase is a crucial one in which the decision to embark on KSAM – or not – is taken. Champions of KSAM look outside at the marketplace for their justification, at what their most important customers are saying and doing, and at what approaches their competitors and other leading companies are taking. Ideally, the KSAM champion defines what success in KSAM would look like for the company and describes the journey towards that success, taking into account outcomes for the company, the individuals involved and the customers. ‘Scoping KSAM’ can be divided into three sub-phases, as Table 4 shows. Phase A may easily take up to a year and involve a good deal more effort, discovery and political activity than anticipated.

Table 4: Phase A sub-phases in scoping KSAM

| Sub-phase | Key actions |

|---|---|

| 1. Creating awareness | Identify a powerful driver, which could be positive but is generally negative. The KSAM champion (often self-appointed), who recognizes the possibility of KSAM as a solution, works to generate awareness of KSAM. |

| 2. Understanding the scope | Appoint a KSAM programme team to work with the champion. Get to grips with how KSAM addresses the issues through research, putting it in context and communicating with stakeholders. Begin to look at which customers would be involved. |

| 3. Making the case for KSAM | Clarify specifics of strategy, objectives, costs and customers. Assemble the business case with what KSAM will look like in the organization and expected outcomes. Position and define the job of key account manager. |

| Milestone: senior management approval | Critical decision point: stakeholders should have been identified and hearts and minds won over. |

Phase A should end with a formal approval decision, but often the process leading up to it is quite chaotic and political. Putting together the business case for a major change like KSAM is very difficult because of the range of implications and the uncertainty associated with assessing a complex position in the future. Most organizations will look for strong justification before taking on KSAM, but the extent of the initiative and the difficulty of quantifying the outcomes still means that they have to take their decision with less than cast-iron proof. Consequently, the convictions of key players and internal politics play a large part in the decision, and the supplier may become committed to KSAM, even though cross-company understanding, assessment and acceptance have not been achieved.

Companies that miss out elements of Phase A may embark on KSAM on a false premise, considering it to be a short-term initiative from which they can readily disengage. When they fail to get a quick and unequivocal pay-back, they may waver in their commitment to the KSAM programme, described as ‘corporate wobble’ by one company (Woodburn 2006), which may have disastrous effects on key account managers and customers who have committed to KSAM. Companies should see KSAM as a longer-term programme and be adequately prepared for the journey.

The KSAM programme is likely to be challenged internally at all stages of its existence, so companies need a good understanding of the financial implications from the beginning. There may be cost savings emanating from KSAM ways of working, but investment is also required, and generally KSAM does not save cost, for two reasons:

- KSAM generally increases the cost of running the customer interface for key customers. Companies often find those resources by withdrawing them from other smaller or less important customers, but the resource requirement is rarely better than cost-neutral.

- KSAM is more likely to increase volumes or maintain business that might be lost, rather than save cost or raise prices (Kalwani and Narayandas 1995; Ivens and Pardo 2008): key customers are adept at bargaining away cost savings but they do award more business to key suppliers.

The business case can look misleadingly unattractive if an unrealistic baseline is used, i.e. if it were assumed that current levels of business would be maintained in the absence of KSAM, whereas in a KSAM-ready marketplace a failure to change the approach to key customers is likely to lead to a decline in business. Such a decline should be applied as the most probable baseline underlying the case for KSAM.

Phase B: Introducing KSAM

The launch phase is often a chaotic period in which the organization finds that it is still ‘making it up as it goes along’, depending on the amount and depth of scoping carried out in the first phase, but it is understandably difficult to coordinate such wide-ranging changes. However, once certain elements are put into place, others need to be implemented within a fairly short space of time – see Table 5. Action should be planned in advance and then implemented simultaneously around the launch. Key account managers are generally appointed at varying times before the launch, but other launch actions should then follow as soon as possible, since delay in completing them has a wide range of implications. For example, key account managers will start developments with customers from the time that they are appointed, sometimes before important support elements are in place inside the supplier, with the resultant danger of making and having to break promises to key customers.

Table 5: Phase B sub-phases in introducing KSAM

| Sub-phase | Key actions |

|---|---|

| 4. Building capability | Finalize goals and the plans to meet in greater detail, highlighting specific, actionable requirements. Appoint competent key account managers with high priority. |

| Milestone: launch | Coordinated launch: though capability building and roll-out are likely to merge in practice. |

| 5. Implementing roll-out | Build specific internal support rapidly so that key account managers can function effectively. Inform the rest of the organization about the new approach. Adopt feedback- and progress-monitoring processes. |

| 6. Reviewing KSAM introduction | Review the introduction and make adjustments to structure and ways of working at an early stage (too soon to review revenue or profit). Publicize good/new practice and actively discourage bad/old practice to make the commitment to change clear: identify issues. |

The appointment of appropriate key account managers is a crucial action: the job should be carefully described together with the competences and attributes required to fulfil it. Key account managers can be recruited internally, from sales and other functions within the company, and even externally from candidates who match the profile. The quick and easy way is to appoint current relationship owners and/or senior salespeople as key account managers, but many of them cannot meet the requirements of the job and removing them, once appointed, causes a great deal of trouble and bad feeling.

Key account teams have an important role in execution as a large part of the ‘specific internal support’ required to ensure delivery of customer commitments, and are best appointed as early as possible. Some suppliers decide that they will set up account teams ‘next year, when we understand better what we're doing’, but by that time the customer is likely to have concluded that the whole thing was just sales talk and empty promises, and withdrawn their commitment, which will be much more difficult to regain.

At the end of the introductory phase, some of the organizational issues that might cause friction and disruption begin to emerge. Cross-boundary issues (whether national, divisional, cultural or just departmental) will undoubtedly arise. If left unattended, they sow the seeds of poor performance against high expectations that will eventually undermine and potentially destroy the whole KSAM approach.

Even at this point there will be people who are already asking for evidence of the value of KSAM in terms of increased revenue, margin or profit. However, KSAM is a medium- to long-term strategy and should be judged accordingly. Meanwhile, companies have specific anecdotes about how KSAM has helped the business with customers which they can use for the purpose of encouragement rather than evaluation.

The later stages

Phase C: Embedding KSAM

Even by the end of Phase B (Introduction), suppliers can see that KSAM is not quite as simple as first envisaged, and there are elements that need to be reconsidered and re-specified. The organization recognizes that it has only reached the end of the beginning and should expect to make further, substantial developments. Organizations that get KSAM all ‘right first time’ do not appear to exist. At this stage there is a period of redefining various elements of the programme that were put in place in Phase B at a basic level, such as the customer categorization criteria, roles and rewards, followed by a period of intense activity to ‘gear up’ to the new perception of the requirement, as in Table 6.

Table 6: Phase C sub-phases in embedding KSAM

| Sub-phase | Key actions |

|---|---|

| 7. Redefining KSAM | Tighten up some elements, such as customer criteria and account plans, in terms of both specification and quality of execution. Relax other elements to allow more flexibility in response to customers and circumstances. |

| 8. Gearing up | Invest seriously in KSAM; in the key account managers, support, feedback and more. Develop processes to operationalize KSAM, to manage it more professionally and to ensure alignment of KSAM strategy with application. |

| 9. Evaluating impact | Clarify expected outcomes of KSAM. Evaluate results versus expectations and impact internally and externally, reviewed by senior management. |

| Milestone: review commitment | Decision on whether and how to continue with KSAM now the organization understands what it is and what its outcomes can be: agree to commit to decision. |

So, for example, in Phase B the selection criteria for key customers usually emphasize current volumes of business, but the limitation of this approach becomes clearer with experience of working with those customers who take large volumes but remain uninterested in closer collaboration. In addition, as suppliers recognize the amount of resource absorbed by key customers, they understand the importance of ensuring that only those who will respond at a satisfactory level should receive such expensive treatment. The criteria for selecting those customers need to be more sophisticated, along with the process for applying them.

Again, key account plans should have been produced in Phase B, but commonly they will be incomplete, lack explicit strategies and have a short-term focus. Suppliers begin to see the need for genuine strategic account plans in whose development the customer has been heavily involved. The plan format is upgraded, more training on producing strategies and plans is delivered to key account managers (and teams, ideally) and the requirement for quality is clarified and followed through.

Process development becomes a major focus. Processes should be adapted to facilitate the implementation of strategies with key customers, whatever their nature, with the emphasis on maintaining flexibility. Since key customers will always ‘push the boundaries’, suppliers developing processes to support them should avoid rigidity and excessive standardization. Effective processes designed to deliver to KSAM needs should replace ‘rules’ and ‘compliance’, unless legally required.

By the end of this phase, the supplier has a functioning KSAM approach that is valued by customers, is properly embedded in the organization and is producing results, but the supplier can still improve its approach to KSAM and get more out of it. The company should take the opportunity to:

- Complete a thorough review.

- Check that the decision to operate KSAM is still valid.

- Gain the unequivocal commitment of all senior and middle managers to KSAM and their role in it, at least.

- Prepare to revise, upgrade, reconfigure and take all elements to another level.

However, evidence that companies complete this very useful stage is patchy, to say the least. If the company carries out a review, and assuming that it confirms the decision to operate KSAM, it should now have sufficient confidence in the approach and the individuals it has made responsible for it to allow KSAM to be delivered with the flexibility and variety that it requires.

Phase D: Optimizing value

By the end of Phase C, KSAM should be really embedded in the company and the supplier should be ready to move on to Phase D, in which it now has the experience and understanding of KSAM to increase the benefits from KSAM and to improve its performance and outcomes. By this stage, the supplier has successfully negotiated difficult issues and identified positive outcomes. With a more confident mindset, companies can embark on making some of the changes that they were unwilling to implement earlier. Internally, operations and management might become more complex (Brehmer and Rehme 2009), but if that complexity allows the supplier to offer more powerful customized solutions for key accounts, then managing that complexity is a valuable capability – see Table 7.

Table 7: Phase D sub-phases in optimizing value

| Sub-phase | Key actions |

|---|---|

| 10. Recommitting | Senior managers recommit to KSAM very publicly and re-energize the programme. KSAM is accepted as a permanent part of the culture and operations of the organization. |

| 11. Integrating KSAM | KSAM and key customers are represented in all major forums and plans. The needs and operation of KSAM are integrated into all relevant business processes. |

| 12. Becoming key-customer centric | Information is seen as central to proper management and is not subservient to traditional metrics. KSAM's strategic position and contribution are recognized and accepted. |

In Phase B, the mediocre quality of the account plans meant that they were probably not good enough to make a contribution to the business planning cycle for the whole organization, but if the quality of the plan has been lifted in Phase C, they should now take up this role. Strategic account plans show the supplier how a very significant part of its business will develop over the subsequent three plus years – where its key customers are heading, which strategies it needs to support and invest in, what resources it will require, what outcomes it can expect and whether the overall direction is aligned with its own strategies. These plans represent an invaluable source of information that should be feeding the development of the corporate business plan, but which will require a defined process to make that input.

Any processes that are intransigent, inflexible and unhelpful to key customers should be investigated with a view to making them more KSAM-friendly. All senior managers and function heads, rather than seeking how KSAM fits into their function's priorities and ways of working, can be proactively exploring what their function can do for KSAM. The needs of key customers are explicitly acknowledged in their plans. Senior managers of all functions are vocally and visibly supportive of KSAM, which is part of the consistent and continuous communication about what KSAM and key accounts mean to the supplier's business that enables the whole company to achieve best-practice KSAM.

KSAM should be fully integrated into the working of the organization at all levels (see Table 8). It now holds a permanent and appropriate place in the structure, the planning cycle, budgeting and resourcing, career development for key account managers, etc. The focus shifts from how to install, communicate and operationalize KSAM to how to manage, implement and extract maximum benefit from the exciting raft of key customer programmes and projects that are enabled through KSAM. KSAM is accepted as the normal way of working: ‘why’ and ‘how’ are no longer challenged and are replaced by a focus on ‘what’ in terms of the business with customers. Key indicators that the company is genuinely operating an embedded KSAM programme include both the wider organization/senior management and key account managers.

Table 8: Signs of embedded KSAM

| Organization | Key account managers |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

With confidence in their own experience of KSAM, suppliers should be able to improve performance further through wholeheartedly embracing the concept of the importance of key customers. That also means that, having developed the people to manage them, key account managers should be fully competent and trusted to take over as the ‘managing director of the customer’ in terms of the supplier's business with them, backed by a suite of management information that readily and accurately represents the position with each customer individually. The company is now ready for best-practice KSAM.

Conclusion

Making the transition to KSAM is not easy or quick. Eventually, it will touch almost every part of the company and people at all levels in the organization, and make changes in the way they work and with whom they work. The early stages, in which suppliers research and explore what KSAM will mean for them, are very important in making the smoothest possible transformation. That is not to say that there will be no resistance to the change because, in our experience, resistance from some quarters is inevitable. Success requires political skills, robustness, persistence and the backing of senior management.

Transitioning occurs through taking action across strategy and planning, the organization and culture, and processes. Early approaches are likely to be revisited as the company learns more about KSAM, and the original idea reworked with increasing sophistication and subtlety. KSAM is not simple: it is predicated on treating key customers individually and differently according to their needs (and those of the supplier), and uniform and standardized approaches and processes will, by definition, not meet the expectations of most key customers. Suppliers start by making fairly superficial adaptations for key customers, but go deeper as they learn from their customer partners and reap the business benefits.

Key account managers that start out as salespeople also have to transform themselves to play their role as a leader. Sensible companies help them in every way to achieve the required level, both through training and development and through removing barriers and supporting them as much as possible. Companies that have strong functional and divisional structures with weak customer orientation are often asking key account managers to execute a high-pressure job in a generally hostile environment, inevitably with limited levels of success and retention.

KSAM teams have become a very important part of the offer to key customers – their broad and mixed skill set and specialized knowledge provide a great deal of the value a customer receives from the supplier. Team members are mostly only partly dedicated to any one customer, so both the organization and the key account manager that leads the team need to make substantial and continued efforts to give and gain recognition for the team, communicate objectives and ways of working, and attract buy-in from team members and their functional heads.

Suppliers with mature KSAM programmes tend to come to the conclusion that the only way they can achieve the business synergies they seek is through a centralized unit of key account managers working with key customers across all geographies and products, not attached to a local or specialist structure. They recognize, however, that this approach still requires major efforts to keep operational delivery links close and realistic. Whatever the structure, successful KSAM requires a willingness to share and to work across boundaries in teams, for corporate rather than territorial objectives.

Competitors catch up, customers want more innovation, and newly appointed directors arrive with different ideas about customer management to challenge the KSAM programme. Alternatively, complacency and slippage can surface if companies become so used to KSAM as ‘the way we do things round here’ that they forget what made it successful. The KSAM approach should constantly be reviewed, revised and kept fresh and up to date. Ultimately, companies need to recognize that transitioning to KSAM is a long haul, but very worthwhile, and maybe even obligatory, in current markets.