Switching costs in key account relationships

Abstract

Companies are increasingly implementing key account management for their most important business customers. Relationships between key account managers and their customers are intended to be long-term strategic partnerships resulting in competitive advantage for both. Switching costs include the psychological, physical and economic costs a customer faces in changing a supplier. The main question we seek to investigate in this paper is whether customer switching costs are good or bad for both the customer account and the selling firm. Further, we examine the factors leading to switching costs so that key account managers may influence the outcomes in these relationships.

Companies are increasingly implementing key or major account management for their most important business customers (Sengupta et al. 1997a). In some companies, these are also called national or global accounts. Key account managers (KAMs) should develop and build long-term relationships with each of their customer accounts. The account manager helps the customer solve operational and strategic problems by providing research and analysis. As part of the deal, the customer commits to large volume purchases of products and services over a long period of time. This is a challenging boundary role suited only for the best sales professionals.

Selected sales management literature has examined the role of the key or national account manager (for an overview, see Weilbaker and Weeks 1997). Numerous conceptual articles and case studies have described the benefits of implementing such programmes, the traits, skills and knowledge required of key account managers, and the environmental conditions under which such programmes would flourish. However, there has not been an integration of the sales management literature with the literature on relationship marketing (Biong and Selnes 1996; Lambe and Spekman 1997a). We agree that such a move is necessary and desirable because relationships between key account managers and their customer accounts are intended to be long-term strategic partnerships resulting in competitive advantage for both.

The relationship marketing literature (Dwyer Schurr and Oh 1987; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Webster 1992 are just a few examples) has a number of constructs, frameworks and empirical generalizations that can be useful to improving the efficiency and effectiveness of KAM relationships. While the relationship marketing literature discusses both vertical buyer–seller and horizontal relationships (Bucklin and Sengupta 1993), KAM relationships fall into the vertical category. An important concept in vertical buyer–seller relationships that can be applied to KAM relationships is switching costs, the focus of this paper.

Conceptual framework and hypotheses

Switching costs were popularized by Jackson (1985) in her study of industrial marketing relationships. She defined switching costs as the psychological, physical and economic costs a customer faces in changing a supplier (Jackson 1985, p. 13). When contemplating a switch in suppliers, a customer faces setup costs and takedown costs (Weiss and Anderson 1992). Setup costs include the cost of finding a replacement supplier who can provide the same or better level of performance than the current supplier or the opportunity cost of foregoing exchange with the incumbent (Dwyer et al. 1987). Takedown costs include relationship-specific or idiosyncratic investments made by the customer that have no value outside the relationship with the current supplier and have to be written off (Anderson and Weitz 1992). The net result of switching costs is that they produce inertia for the customer to remain in the relationship with the current supplier.

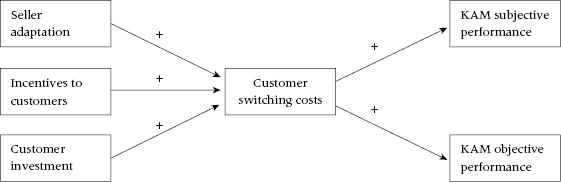

The main question we seek to investigate in this paper is whether customer switching costs are good or bad for the customer account and the selling firm in key account relationships. Further, what factors lead to the creation of switching costs so that key account managers may exert some influence over the outcomes in these relationships? To this end we develop a conceptual framework (Figure 1) incorporating relevant antecedents and consequences of switching costs based on the existing literature.

Figure 1 Conceptual framework

Antecedents of switching costs

In the relationship marketing literature, much has been written about the concept of interfirm adaptation (Dwyer et al. 1987; Johanson et al. 1991). Adaptation promotes efficiency and brings about balance between an organization and its environment (Johanson et al. 1991). In key account relationships, the selling firm often faces changes in its own or customer environment that call for adaptation in products, policy, systems or organization. Seller firm adaptation has symbiotic benefits for both seller and customer. For instance, like many other corporations (Spiro 1996), Marriott faces the technological challenge of fixing the ‘Year 2000’ problem in its online reservation system which will affect all its major customers and travel agents. To the extent that this technological adaptation is successful, Marriott increases its value to its key customer accounts. Most key customer accounts appreciate flexibility on the part of their suppliers. The enhanced value from seller adaptation increases customer switching costs in relation to other potential suppliers. Thus, we put forth our first hypothesis:

H1: The greater the adaptation undertaken by a selling firm, the greater the switching costs faced by a customer account.

The underlying rationale for key account management is that when selling firms focus their resources on serving a few important customers, it pays off in terms of sales and profits (Sengupta, Krapfel and Pusateri 1997). A major item of promotional expenditure in key account sales is ‘push’ money. When dealing with retail customers, for example, manufacturers may offer slotting allowances for carrying new products or special allowances for in-store promotions (Greenwald 1996). Another form of incentive offered to key customers is aimed at creating ‘pull’ or loyalty with their end-users through co-branding or joint advertising efforts. For example, Black and Decker made use of both ‘push’ and ‘pull’ incentives in launching its DeWalt line of power tools through key retailers like Home Depot (Dolan 1995). When such incentives are offered by the selling firm, they also create customer switching costs in relation to other potential suppliers. This leads to our next hypothesis:

H2: The greater the incentives offered by a selling firm, the greater the switching costs faced by a customer account.

Relationship-specific investments are investments in assets which are specialized to the exchange relationship (Heide and John 1988). If the relationship were to be terminated, the value of these assets would be largely lost because their salvage value outside the relationship is very low. For instance, a customer of ocean shipping services may have to invest in containers and material handling equipment tailored to the ships and dock facilities of a particular carrier. If the customer wanted to switch to a new supplier, it would have to forego this investment and reinvest in containers and equipment for a new carrier. In a similar vein, selling firms sometimes ask key customers to invest in customized hardware and software so that they can do electronic data interchange (O'Callaghan et al. 1992). Such non-redeployable assets give rise to switching costs (Heide and John 1988):

H3: The greater the customer's relationship-specific investment, the greater the switching costs it faces.

Jackson (1985) suggests that switching costs are likely to be higher when the product is technologically complex and requires a high level of service to be provided to the customer. While we do not put forward a formal hypothesis for product complexity, we do include it as a control variable antecedent of switching costs.

Consequences of switching costs

Switching costs create dependence of the customer on the supplier (Morgan and Hunt 1994; Biong and Selnes 1996). The questions is, is this dependence good or bad for the relationship? The earlier literature on sales management and channel theory (summarized in Gaski 1984) suggests that in conventional arm's length relationships, this situation of asymmetric dependence is good for the selling firm which can exploit the dependence of the customer. However, key account managers cannot be so short-sighted. For a different approach, we turn to insights from relationship marketing.

Dwyer et al. (1987) propose that when a relationship develops over time, the two parties gain experience and learn to trust each other. Consequently, they may gradually increase their commitment through investments in products, processes or people dedicated to that particular relationship. The customer may incrementally invest resources in the relationship and voluntarily increase its switching costs and dependence on the supplier (Anderson and Narus 1991). Dwyer et al. (1987) suggest that the customer's anticipation of high switching costs gives rise to the customer's interest in maintaining a quality relationship. These anticipated high switching costs lead to an ongoing relationship being viewed as important, thus generating commitment to the relationship.

Morgan and Hunt (1994) found a direct, positive empirical relationship between termination costs and commitment, a negative relationship between commitment and propensity to leave, and a positive relationship between commitment and cooperation. Biong and Selnes (1996) found a positive relationship between dependence and continuity of the relationship. Therefore, switching costs should result in favourable relationship outcomes for both parties.

KAM performance depends on favourable relationship outcomes for both seller and customer. The selling firm is more interested in achieving financial objectives such as account market share, sales volume and profitability. However, the key customer is more interested in meeting their own objectives and being satisfied with the products and services provided. Thus, we conceptualize two dimensions of KAM performance, subjective and objective. KAM subjective performance is what the KAM accomplishes for the customer in terms of meeting the latter's objectives, continuity, cooperation and satisfaction. KAM objective performance is what the KAM achieves for the selling firm. We put forth these final two hypotheses on the relationship between switching costs and KAM performance:

H4: The greater the switching costs faced by a customer account, the higher the subjective performance of a key account manager.

H5: The greater the switching costs faced by a customer account, the higher the objective performance of a key account manager.

In testing the last two hypotheses, we include seller firm size, a proxy for resource availability, as a control variable that can affect KAM performance.

Data collection

This study is part of a larger study that the National Account Management Association1 (NAMA) commissioned us to do in spring 1996 on best practices in key account management among its member companies. We began our study with in-depth exploratory interviews of five key account managers (KAMs) and their supervisors with the aim of obtaining face validity for our framework and generating items to operationalize our constructs.

Following the exploratory interviews, a structured survey questionnaire was designed to tap into all the relevant constructs in our framework using multiple item Likert scales wherever feasible. We borrowed items from existing literature where available and formulated our own questions for new constructs. The survey questionnaire, reply-paid envelope, and requests for participation were mailed to 528 NAMA members in February 1996. One hundred and seventy-six completed, usable surveys were returned, giving a respectable 33% response rate. Our respondents were front-line KAMs from a broad cross-section of US firms across many different industries (55% manufacturing, 43% service). Firms represented were large, with median sales of $3 billion and 14,000 employees. Our KAM respondents had a median age of 41 and were well-educated (61% had a bachelors degree, 28% had a graduate degree). They had a long tenure within their firm, median 12 years, 10 in sales and of those, 3 as a KAM.

Each respondent provided data for a specific customer account they were responsible for. If they handled three or more accounts, they were asked to provide data on the account they spent the third largest amount of time with. If they handled two accounts, they were asked to provide data on the account they spent the largest amount of time with. If they handled just one account, they provided data on that account. This procedure was followed to minimize self-selection bias in the reported account.

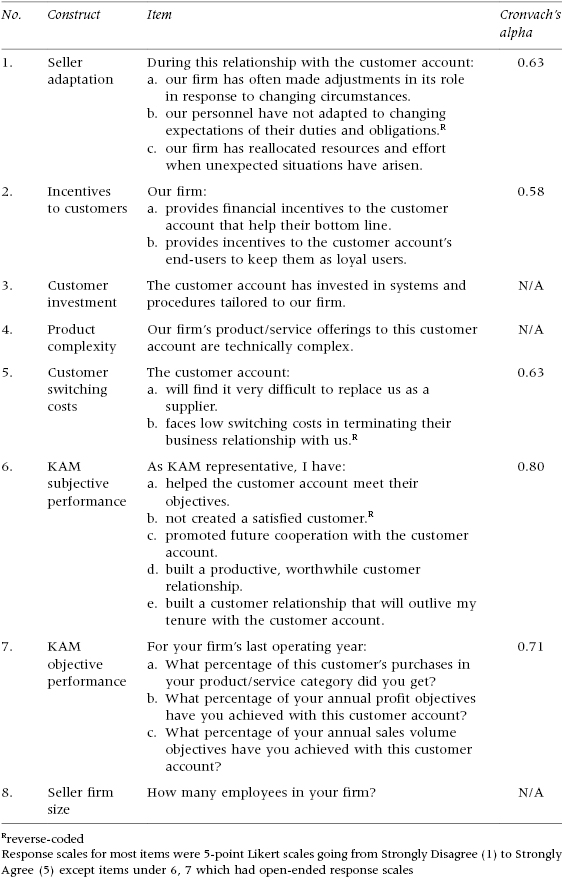

A reliability analysis was done for each multiple-item variable. Some individual items were dropped to increase reliability using Cronbach's alpha. The final operationalization of variables along with respective Cronbach's alphas is reported in Table 1.

Table 1: Variable operationalizations and reliabilities

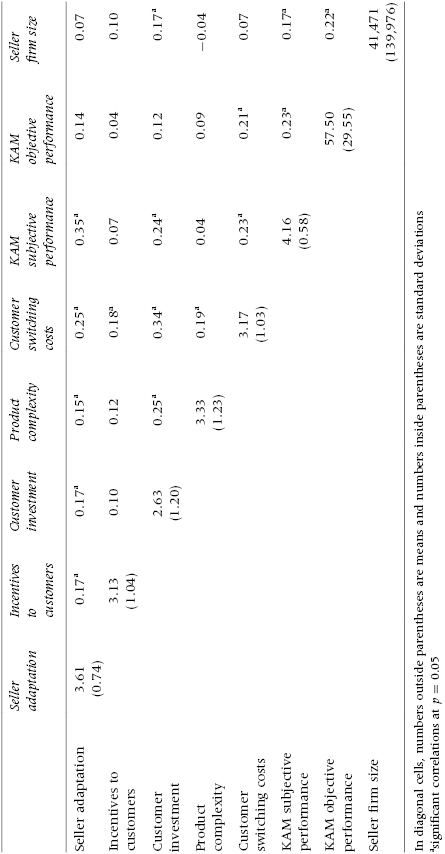

We also did an exploratory factor analysis on all 18 items in Table 1 and found that they load cleanly on the underlying 8 factors. This provides some evidence for the convergent and discriminant validity of our measures. Means, standard deviations and correlations for all our eight variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Means, standard deviations, correlations

Results

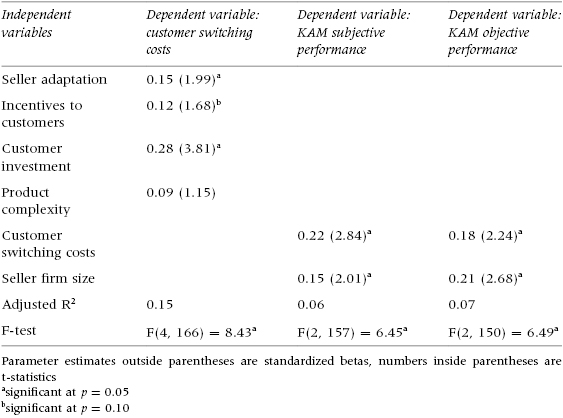

In order to test our conceptual framework and hypotheses (Figure 1), we used path analysis with ordinary least squares regression. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Ordinary least squares regressions

In column 2 of Table 3, we regress customer switching costs against the three antecedent variables – seller adaptation, incentives to customers, customer investment – and the control variable, product complexity. We find that seller adaptation and customer investment are strongly and positively associated with customer switching costs (H1, H3), while incentives to customers are weakly and positively associated with switching costs (H2). Contrary to expectation, product complexity was not related to customer switching costs in our sample.

In column 3 of Table 3, we regress KAM subjective performance against customer switching costs and seller firm size. As expected, switching costs were strongly and positively associated with subjective performance (H4). In a similar vein, switching costs were strongly and positively associated with KAM objective performance (H5) in column 4 of Table 3. Seller firm size had a positive significant relationship with both KAM subjective and objective performance in Table 3.

The explained variance in the dependent variables in Table 3 is modest, indicating that our study omitted some variables that also affect switching costs and KAM performance.

Discussion

In this paper, we have demonstrated the importance of customer switching costs in key account relationships. Customer switching costs have a significant positive impact on both aspects of performance – the achievement of seller firm objectives based on objective criteria such as account market share, sales volume and profitability, and the achievement of customer objectives and satisfaction by more subjective criteria. They help to achieve a win–win for both parties in the relationship. This is a marked departure from conventional thinking in adversarial relationships where customer switching costs were considered good for the seller but not for the dependent buyer.

What is the mechanism by which this win–win is achieved? As our results indicate, the biggest factor that gives rise to customer switching costs is customer investment in relationship-specific assets. If this was the only factor at work, it would make the customer dependent on the supplier and the relationship unbalanced, with unfavourable relationship outcomes.

However, our results show that relationship-specific investment by the customer is not the only factor affecting customer switching costs. There is a dependence balancing mechanism at work by way of seller adaptation. Notwithstanding customer relationship-specific investment, the adaptability or flexibility of the seller firm demonstrates to the customer that the seller is not going to be opportunistic or exploitative. This is reassuring to the customer, helps balance the relationship, and further increases the commitment and switching costs of the customer. This reciprocity or balance is the essence of the win–win in key account relationships. The value of balance or mutual dependence, sometimes called interdependence, has been studied in a channels context with results consistent with our own (Gundlach and Cadotte 1994; Kumar et al. 1995).

Interestingly, we found that ‘push’ and ‘pull’ incentives offered to customers do not do much to increase customer switching costs. Customers seem to value adaptation in a long-term relationship more than short-term financial incentives. While adaptation does require investment on the part of the seller firm, this may be a more cost-efficient use of resources than directly offering incentives. The soft-sell of adaptation may yield better results than the hard-sell of push–pull money in key account relationships.

Finally, when we look at the empirically validated antecedents of customer switching costs, we realize that creating these is the responsibility of the entire selling firm, not just the responsibility of the individual KAM. In order to adapt, the selling firm will need to allocate resources from all over the organization in order to solve specific problems that come up. The KAM can bring the requirements to the attention of the selling firm and can do his or her share of internal marketing. Ultimately, a higher level of management within the selling firm must take responsibility for allocating the necessary resources for adaptation or financial incentives.

Notes

From Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, vol. 17, no. 4 (Fall 1997): 9–16. Copyright © 1997 by PSE National Educational Foundation. Reprinted with permission of M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Not for Reproduction.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the National Account Management Association (NAMA) in collecting the data for this study. This article was invited and did not go through JPSSM's regular review process.

1 Now Strategic Account Management Association (SAMA).