The strategic buyer: how emerging procurement strategies may support KAM/SAM relationships

Abstract

This paper reviews key strategic account management from a purchasing and supply perspective. The purchasing function has experienced a major strategic shift in the last 20 years. More professionals are highly qualified, well remunerated and great strategists.1 The article looks at the increasing adoption of an interaction approach by purchasing – we are interested in how purchasing contributes to business performance by placing collaboration with key suppliers at the centre of its strategies, why trust-based relationships are important and how innovation can be gained from partnerships with key suppliers.

Introduction

A strategic account is a source of significant benefit to an organization's prosperity and future development. Customers are also increasingly stating that suppliers are among their most important assets. Scan the annual accounts of most leading corporations and suppliers not only warrant a mention, they are cited as a vital resource. Apple and Nike, to name but two, list their suppliers in their annual statements and on their websites, emphasizing the importance to their own brand reputation of their suppliers' capabilities and reputations. Mutual dependence is becoming a way of life for world-class supply organizations. Furthermore, the financial and technological advantage to be gained through world-class supply management has positioned the function into a core role in corporate governance.

In this paper, the focus is on a customer's view of their upstream supply. Critical issues on the agenda for supply professionals are discussed, opening with the strategic and financial importance of their role and the advantage that can be applied to corporate performance through strategic purchasing decisions. Achieving such influence requires attention to building collaborative relationships with suppliers, central to which is the phenomenon of trust. While trust is often talked about as though it is a ‘soft’ or intangible characteristic arising from human interaction, we will examine the notion of the economics of trust, aiming to articulate some of the tangible or quantifiable ways in which a number of thought leaders and practitioners build their case for more attention to the dynamics of interaction between the actors in a buyer–seller relationship.

Managing interaction between supply chain partners has become an imperative, one that reflects the view that ‘competition no longer takes place between companies but between supply chains’. Since this phrase became popularized by Professor Martin Christopher of Cranfield University in the early 1990s, it now reverberates around the halls of corporate HQs and academia alike, a homily that has become a modern-day trope for business. Aligning supply chain partners to a common purpose, however, is not such a simple process. Clarity of purpose and clear consistency of decisions to that purpose are, at the very simplest level, the key requirements for alignment between supply chain partners. If an organization cannot get its suppliers to align with its own strategic aims, this causes significant problems for the execution of strategies in support of those aims. In essence, this is at the heart of our concern for buyer–seller interactions in this paper.

We examine some of the challenges that arise when one side to a transaction fails to account for the other's position and power in the transaction. As much as we would all like to exert power over our partners in business, this is clearly not the case, and the use of purchasing portfolio and customer portfolio analyses provide an insight into how misalignment can emerge from one-sided strategic analysis.

The point of building collaborative relationships with suppliers is very much in response to the demands presented by rapid technological innovation, shortening life cycles and step-change transformation. We see the move towards collaborative innovation as gaining significant momentum under such dynamic conditions. Apple, Procter & Gamble, Nike (and many others) are using the power of their suppliers' technical capabilities to work collaboratively on their product and service innovations. Such collaborative innovation is characterized by interdependence tempered with a clear view of where the locus of change can most readily emerge.

The article concludes by examining how the role and contribution of purchasing function and purchasing professionals continue to transform given the pressures and opportunities we discuss here.

The strategic importance of purchasing

Strategic account management is increasingly being considered as one of the components of supply chain performance. Interest in global supply chains reflects their increasing importance to our economic life. In 2009 world exports of intermediate goods exceeded the combined export values of final and capital goods, representing 51% of non-fuel merchandise exports,2 indicating the importance of business-to-business transactions on a global scale. Thus as global economic systems have become highly interconnected, with many consumer products tracing their supply chains across multiple continents involving a range of industries, organizations cannot operate as if they are in a vacuum.

In addition to the shifts in global economic activity, localized events are having a more pronounced impact on global business prospects. Major natural disasters such as the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, the Thai floods that same year, and human-caused disasters such as the Rana Plaza building collapse in Dhaka, Bangladesh in April 2013 have been seen to reverberate around the world. These tragedies had a significant human toll, but also exacted a profound effect on business activities across the globe. Supply shortages arising from the events in 2011 closed many auto manufacturing sites around the world, disrupted computer production, led to increased prices for memory chips and impacted market deliveries. The media coverage of the Rana Plaza collapse claimed that it occurred partly as a result of low-cost country (LCC) sourcing strategies employed by Western fashion brands, which led to a major reassessment of their collective responsibilities for ensuring safer supplier working practices, conditions and facilities. Looking to suppliers for a proactive approach to supply chain safety and disaster response is one of the building blocks of supply chain risk strategy. Relying on ‘good partners’ who share in the analysis and response phases of risk management can help avoid recent event biases and provide direct input to contingency plans.

Corporations are increasingly sensitive to the political impact of their strategic decisions relating to global sourcing; the debate whether to offshore, near-shore or re-shore has implications far beyond the walls of the boardroom. In 2010 Steve Jobs, former Apple CEO, responded to President Obama's query about why Apple did not manufacture in the USA with the now infamous statement that ‘those jobs aren't coming back’. As an indication of how political sensibilities can shift corporate strategy, by 2012 Apple's new CEO Tim Cook had taken a more positive position on the company's global production system, which led to re-shoring of Mac Pro production to Texas. This required manufacturing suppliers to refocus on the strategic advantages of local sourcing for Apple, such as speedier delivery, shorter supply lines and lower total costs. Getting ‘inside the head’ of the customer in this instance was a critical driver for the sourcing decision and their supplier's account management teams had a major role to play in both the evaluation and execution of a viable near-sourcing plan.

Securing vital resources for production can be a major challenge if it so happens that your major input is an endangered species. Taylor Guitars of California faces immense challenges in securing the woods needed to provide the high sound quality and durability from a number of endangered timber species such as mahogany. One strategy the company has adopted is to collaborate with a Spanish furniture manufacturer to acquire a mahogany plantation in Cameroon, thereby securing a sustainable source of supply while simultaneously ensuring that there are more socially responsible practices being employed in the company's supply chains.

Thomas Friedman's thesis in his highly popular (and populist) book The World is Flat is that key changes in technology and global sourcing, plus the emergence of both large and developing economies in China, India, Brazil and, to a lesser extent, Russia, were driving more interdependent, collaborative and open global supply chains. Taking the discussion further in terms of our interest in account management and purchasing, Håkansson and Snehota (2006) state in their influential article ‘No business is an island’ that this interdependence between actors in networks requires that business strategy decisions need to be reoriented to embrace the context of the networks in which businesses find themselves.

In the purchasing field, the importance of managing across boundaries with suppliers has long been viewed as critical to the strategic success of the firm, with Monczka and Morgan (2000) highlighting in particular the impact of an increasing trend for outsourcing, LCC sourcing and collaborative design. Thus modern business practices have embraced the notion that to produce goods and provide service experiences they will have to increasingly rely upon an extended network of suppliers, collaborators, service providers, distributors and customers, all of whom have a significant impact on their performance and development.

When we begin to think about the ‘extended enterprise’ (Dyer 2000) as the mechanism through which competitive activity takes place, decisions about the nature of strategic relationships between customer and supplier, the potential for capitalizing on the creative power of multiple actors and the importance of collaborative operations begin to take the front seat in how such decisions are shaped. The purchasing function, by virtue of its role as a boundary-spanning function, naturally has a major part to play in such decision-making, but it cannot operate alone.

The healthcare sector in the USA has considerable cost and profit pressures due to governance structures, which have increasingly expanded the strategic role of purchasing and supply functions across the sector. The costs associated with medical products and service provision, technology-driven price inflation, demographic pressures, diverse stakeholder pressures from clinicians and administrators, challenges of managing complex inventory systems and the criticality of providing responsive service levels are the key challenges in this sector. For many supply professionals, it is the management of inter- and intra-organizational challenges that causes the greatest headaches:

“Our consultant surgeons are amongst the best in the world, are at the top of their game. They work closely with the local university, again, one of the best medical research schools in the world. So, we are frequently at the leading edge of medicine. Which presents me with big problems trying to get a good deal on some of the new equipment that is still at an early stage of development.

My job is to provide them with the best value for money products, tools and equipment, which may clash with what they want – typically they only want ‘the Rolls-Royce’ instruments. And to be honest a lot of people around here think that makes them some real SOBs! Sure, they are opinionated, egotistical and at times self-righteous, but I would be too in their shoes. So, I find it really helps to listen to them, figure out what is important about their needs and ask their advice. I always put it this way: ‘I'm here to make it easy for you. I'm not a physician, but I am a market expert – I can search the market, evaluate the options, provide you with a thorough breakdown and then together we can figure out our best choice.’ That seems to work well most of the time.

My job is really about financial stewardship, but since we are not a manufacturing business, but a caring business, I find it better to couch this in terms that resonate with whoever I'm talking to – but the bottom line is, it's about the bottom line!”

Ryan Harrison, Buyer

“A lot of our consumables are really pricey – we spend millions on infection-prevention supplies. A few years back we were buying from around 300 different suppliers in this category alone and it was impossible to manage relationships, gain economies of scale or be sure our costs were contained. So many users within the hospital group were ordering directly off of suppliers, we had some major work to do to bring that all in line.

Then we reached out to one of the major distributors in the sector and were pretty candid with them. ‘We need to consolidate our supply base and reduce our total spend by 25% in the next year. How can you help us?’ They embraced this with open arms and not only helped meet our targets, but their intranet is aligned to ours so users can order with ease and we have 100% transparency as well as really great pricing and discount deals.

I know how competitive our purchasing was – this is the third hospital district I have been at in seven years and I still have good ‘intel’ on my previous hospitals. I know they came in and really pulled out all the stops for us. As a result, we have just 30 suppliers in the category now and (X) is our number one strategic alliance partner. They even have a team permanently located on one of our central sites to help monitor, manage and evaluate our supply. This has been a great partnership so far and our financial impact has been pretty impressive, saving the group over $1.5 million in the last year alone.”

Jose Ottega, Vice-President

Supply base reduction can be a major opportunity to turn a customer into a strategic account. Naturally, this depends on scale (can you provide all of the products and services in an enlarged category?), but it can also mean that a more collaborative position with current competitors and suppliers is necessary to deliver the full service expected from sole sources. It is also critical to realize that this move to a smaller supply base is not just about trying to secure economies of scale. The notion here is that buyers are seeking ‘full service supply’ as a means to gain value-added benefits from their suppliers, such as vendor-managed inventory (VMI), synchronous delivery, or service innovation. Fortuitously, this also resonates with many in strategic account management – adding value through service (Grönroos and Ravald 2011) offers significant potential for business growth.

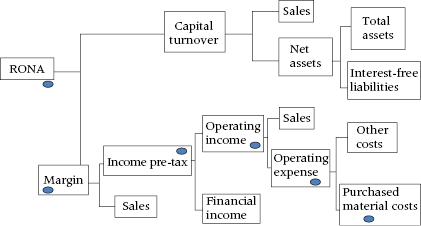

Given the focus that many organizations place on the evaluation of purchasing policies, practices and projects, financial literacy is an important attribute. The ability to articulate the benefits of purchasing actions and strategies across the business in a convincing manner is a fundamental skill purchasing executives need to acquire. One framework that has been used to promote the impact of the function has been DuPont ratio analysis (illustrated below), which was originally developed by the DuPont Corporation in the 1920s.

Using basic financial ratio analysis, DuPont analysis indicates the hierarchical relationships that exist between purchased material costs and return on net assets (RONA), as illustrated by the highlights in Figure 1. The use of ratio analysis as a means of presenting the impact of purchasing decisions helps convey a consistent message across the business, where responsibility for specific elements of financial performance is shared – for example, the connection between operating income and purchased costs is a significant shared concern between purchasing and operations. So while it has been acknowledged that communication skills are critical for purchasing professionals (Guinipero and Pearcy 2000), the calibre rather than the content of such communications has been the dominant focus of research (Claycomb and Frankwick 2004).

Figure 1 DuPont ratio analysis model

The Institute for Supply Management3 has stressed financial literacy as a core component of purchasing's internal and external communications with stakeholders. Expect buyers to focus increasingly on the RONA/ROI of any purchase contract and relationship. At the very least, it helps to be able to measure the financial benefits available over the life cycle of your products or services. This makes great sense for most marketers – identifying the economic value to customers is a core marketing concept – but it is also becoming an aspect of financial literacy for buyers.

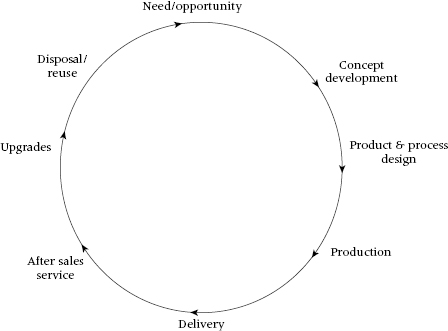

In addition to DuPont ratio analysis, life cycle cost analysis (LCCA) is becoming a critical analytical approach used by purchasing professionals, emphasizing the importance of a focus on total cost rather than price in the evaluation and management of supplied goods and services. Figure 2 indicates the main building blocks of a simple LCCA.

Figure 2 Life cycle analysis

Building an LCCA requires data and participation from across the business and from suppliers, as Case Example 3 illustrates.

“We have to buy at the lowest price for sure, but unlike back in the days when that was the prime issue, now our burning platform is to lower total life cycle costs. I can't do that on my own. I need the estimators, operations, maintenance and finance guys from across the (Y) sector of our business. But I also need DoD (Department of Defense) and the Navy since they're our customers. Suppliers have a massive role to play too – after all, we outsource so much manufacturing and assembly now that they are the ones with the first-hand experience and knowledge.

It doesn't help that our prime suppliers are also our biggest competitors though. Trying to get them to share what they think is proprietary data is a real pain. So the best we can do sometimes is give it our best guess. Well, we do more than guess as we have pretty good knowledge around the place that helps us build our LCCA models, but in the end, it is a guess. We do have one supplier account manager (Z) who is amazing and will really go the extra mile with us on LCCA and most efforts we have to build closer working together. But they're unusual. This industry is an insular, exclusive and very protective one. Everyone thinks they own the secret to the Holy Grail and are not willing to share it!”

James R. Smithers, Vice-President

The role and skills required by purchasing professionals have been shown to have changed as the purchasing has shifted from tactical to strategic (Burt et al. 2003; Guinipero and Pearcy 2000), shifting the emphasis to negotiation, interpersonal and teamwork skills in addition to enhanced technical skills (such as financial literacy). Croom (2001) and Bowersox et al. (2005) discuss the strategic role of the purchaser as embracing two distinct sets of skills: operational/technical skills and relational/interaction skills. Competence in the operational ‘stagecraft’ of supply – sourcing, contracting and negotiating – has long been at the heart of a purchasing professional's success. Nevertheless, an increased focus on the softer skills associated with building long-term, collaborative relationships to drive innovation is recognized as central in any function aiming to influence its network of stakeholders. That the IMP (Industrial Marketing and Purchasing) Group expounded on this issue in the early 1980s merely underlines the significance of adopting a relational network perspective when thinking about business practice. It also aligns with the increasing importance given to the need for SAM/KAM (Wilson and Millman 2003) to operate within a dynamic organizational context to resolve customer problems and challenges.

“We don't actually manufacture anything! All of it is outsourced, but that does not mean we don't manage our manufacturing chain. I spend at least two hours every day video conferencing with our factories in China, Taiwan and Vietnam. I used to be on planes all the time, but now I travel probably once every five or six weeks at most. Not only do I video conference (with HD-quality video) but we all share exactly the same databases and ERP [enterprise resource planning] systems, use wikis and blogs to help build our knowledge management as well.

I have great relationships with the teams at all our supplier manufacturing plants since I have met all of them multiple times over the years. Video conferencing also means we can archive the calls, and I can make sure we have translators involved in the calls to help clarify technical points or emphasize any issues. If there's a problem, I can be woken at night and deal with it within minutes. I do send engineers and experts into the plants as and when needed and I know we have developed some unique cross-cultural working relationships with our plants.”

Supply Chain Manager, Cisco Systems

Building close working relationships with suppliers has been one of the key transformations in the roles and responsibilities of purchasing and has been heavily explored from an academic perspective (Spekman and Carraway 2006). Gadde and Snehota (2000), for example, state that ‘developing partnerships with suppliers is resource-intensive and can be justified only when the costs of extended involvement are exceeded by relationship benefits’. Building on this, both Möllering (2003) and Johnston et al. (2004) found in their research that close, trust-based relationships do not mean that these relationships will become collaborative or strategic – an issue we will return to in ‘Power-based relationships’, below. Emphasizing this point, Cousins and Spekman (2003) found that purchasers' motivation for partnership relationships was primarily cost-based rather than to drive collaborative innovation or reduce time to market. There is still a dependence on price-based negotiations, relative inertia in buyer–supplier relationships and a more arm's-length form of interaction. In these cases (Beth et al. 2003) we will still encounter tactical-based relationships with purchasing, and it is also likely in these cases that efforts to build a strategic account relationship will emphasize critical internal stakeholders who exert far more influence over sourcing and supplier relationships than the purchasing department. In this paper we are addressing strategic shifts in purchasing, which means there are laggards as well as leaders.

The economics of trust

One topic that has been significant in the supplier relationship literature is trust, recognized as a major issue in determining the nature of supplier–customer relations. It is viewed as a foundation for cooperation and as the basis for stability (see, for example, Dyer et al. 1998; Helper and Sako 1995; Lamming 1993; Sako and Helper 1998), and it has been argued that it can be a significant source of competitive advantage for suppliers and buyers (Cousins and Stanwix 2001; Zaheer et al. 1998).

Kim et al. (2010) conducted a dyadic study of cooperative buyer–seller relationships, finding that switching costs and technical uncertainty – in essence, inertia for changing suppliers – were far more significant determinants of supplier relationships for buyers. This contrasted with suppliers in the same relationships who had a much higher concern for reciprocity in the relationship than their customers. However, relatively few empirical studies have been conducted into trust-based supplier relationships, as noted by Emberson and Storey in 2006. There has been a more concerted effort to examine trust-based relationships and relational strategies in the SAM/KAM literature. Guenzi et al. (2009) found that employing a strong customer (or customized) orientation has a significant impact on building trust with customers, along with employing cross-functional teams for the account interactions (see also Gounaris and Tzempelikos 2012; Guesalaga and Johnston 2010; Zhizhong et al. 2011). De Ruyter et al. (2001) and Gosselin and Bauwen (2006) have also emphasized the importance of a customized approach to managing relationships with customers in order to enhance the integration between the two parties. De Ruyter et al. in particular found a strong connection between commitment to a customer and trust between customer and supplier as having a positive impact on the development of the strategic account relationship, findings validated by Alejandro et al. (2011).

The drivers and consequences of trust have been addressed in a fascinating article by Paul Lawrence and Robert Porter Lynch and published as a leader article in European Business Review (Lawrence and Lynch 2011). They set out a compelling catalogue of success stories and principles for collaborative innovation, and provided a clear support for the principles of trust-based relationships. Porter Lynch in particular has been an active exponent of the value of trust-based relationships and much of his work reflects the works on the economics of trust by Stephen M. Covey Jr (Covey and Merrill 2008) and others.

Research into the impact of behaviour of individuals and groups on economic decision-making has been growing in the last two decades. Pollitt (2002) discusses the increasing interest for economists of social capital and highlights the impact that trust between management and employees can have on innovation, citing HP, 3M and UPS as three exemplars of how encouraging social interactions and trust building can stimulate corporate levels of innovation. The new field of behavioural economics essentially questions the validity of long-held assumptions of rational behaviour by market actors (for example, the work of Dan Ariely). In examining the impact of positive and negative emotional responses upon economic decision-making, Andrew Oswald has written extensively on the ‘economics of happiness’, his thesis being that it is possible (and valuable) to model the behavioural, social and psychological effects of economic activity. The corollary for supply relationships is that one could expect to find a significant variation in economic performance because of different behaviours within and across the dyadic links between supplier and customer.

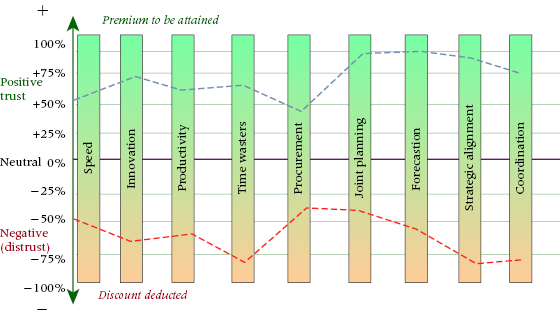

In The Speed of Trust (2008), Covey claims that ‘trust makes the world go around’, exploring the strategic and economic value of building trust within and between organizations. Very much in line with the behavioural economists' theses, he highlights the importance of trust between customer and supplier not just as a ‘social virtue’ but as having clear economic benefits in speeding up interactions and lowering costs. Covey argues that as trust in a relationship reduces, it takes longer to get things done. Process inefficiencies emerge, costs increase and revenues decline, thereby constraining profitability. Beth et al. (2003) discussed this in their Harvard Business Review panel discussion on relationships, noting the premium earned from high-trust versus low-trust relationships. Porter Lynch has illustrated this graphically in Figure 3.

Figure 3 The Economics of Trust Framework

Note: With thanks to Robert Porter Lynch

The methodology used, which we have employed at the University of San Diego Supply Chain Management Institute for many years, is to solicit executives to analyse two supplier relationships – one that they consider ‘high trust’ and another they consider ‘low trust’. Discussion then takes place around the performance and operational characteristics of interactions and processes with each supplier. If possible, actual performance metrics are used to discuss the advantage of high trust over low trust in dimensions such as speed of response, degree of supplier-led productivity (cost) and effectiveness – see Figure 3 for an illustration of the framework. We typically find a performance advantage of 60–110% for high-trust supplier relationships over low-trust.

This is a critical tool for both buyers and SAM/KAMs in presenting the case within one's own organization for adapting relationships with strategic partners. Trust is also a major asset in building strategic relationships, as Case Example 5 illustrates.

John McCallum is the Vice-President of Banking Operations at GlobalBank Corporate Services in Phoenix, Arizona. Mail operations spend for the bank is around $28 million per annum, all of it outsourced to three suppliers. Supplier A is John's ‘high-trust’ supplier and Supplier B his ‘low-trust’ supplier:

“A and B are both fairly competent suppliers, they are regarded as the top two in the industry and use much the same technology and processes as each other. When we visit their operations, to be honest you would at first be hard pushed to tell much difference – but boy, do we have polar opposites there.

I love working with A – their account team and service guys are available 24/7, know my people by name and are always checking how things are going. Their account management approach means they review their weekly performance with us by comparing data and have adapted their metrics to suit our experience (and to be honest, told us where we are measuring things the wrong way, like on-time delivery). We had one issue where a major mailing campaign had been incorrectly packed – one of the inserts was missing. They caught it before it went out and started reworking the whole batch of 450,000 overnight, resulting in the mailing hitting the mailboxes only one day later than planned but with no errors. And they remitted us the cost of the mailing.

Supplier B, however, is very confrontational almost as their default state. We have to call them, constantly monitor their performance and if ever there is a problem we spend too much time haggling over blame rather than resolving the problem. If I could I would put all my business with A, but they just don't have the capacity available when we need it – our mailings run in cycles which sometimes overlap with their other customers' cycles.

When I went through the economics of trust exercise I didn't at first buy into it 100%, but when I did the analysis (I called back to the office three times over lunch to get the data right) it was clear that we get a 30–40% total cost advantage from A through significant efficiencies and performance benefits even though the prices we pay look much the same. Less hassle, more improvement ideas and just a much easier way of managing our campaigns. It's now an important question I ask of our suppliers – ‘What is your key account strategy’ – as I want to know they are focused on serving their customers.”

John McCallum, Vice-President

Over the course of 15 years of running executive events across the world, our informal data gathering typically indicates a ‘value advantage’ for high-trust over low-trust relationships. Trust is often considered in the literature to be ‘built over time’, the consequence of multiple interactions between the parties to a long-term relationship (Sahay 2003). It is not something that ‘just happens’ but is a result of a conscious effort to build the relationship by both parties, customer and supplier.

There remains general disagreement over whether trust can be intentionally created and managed in an economic environment (Blois 1999). It is contended (Sydow 2001) that the processes, routines and settings in a relationship that can influence the development of trust can be managed and that even if trust cannot be managed, the agents ‘can certainly act in a trust-sensitive way when building and sustaining inter-organizational relations or networks’.

In building high-trust relationships one of the primary aims is to achieve improvement in the alignment between the activities of suppliers and buyers. Increasingly this is considered to be the fundamental strategic role for purchasing – much as it is for strategic account managers.

Strategic alignment

At its simplest, individuals at various organizational levels should agree on criteria such as cost, quality and flexibility, whichever are believed to be crucial to the success of that organization (Boyer and McDermott 1999). This internal consensus is considered to be an important requirement for developing the alignment between an organization and its external environment in order to achieve competitive success (Miles and Snow 1978).

One of the more recent schools of thought in the field of strategic management, the resource-based view (RBV), emerged more than 20 years ago and provides a valuable insight into competitive advantage. According to one of the pioneers of the RBV, Jay Barney (2001), organizations improve their performance by employing competitive strategies based upon their capabilities. But the dynamic nature of strategic capability (Teece et al. 1997), the idiosyncratic nature of such capabilities and at times the fact that capabilities can even be thought of as somewhat ethereal (‘you know it when you see it’) may mean that even the firm itself may not understand its true capabilities.

Capabilities are essentially contingent – their very existence depends upon the environment or relationship networks within which they are deployed – and thus the core concern in the RBV for our consideration is how such capabilities arise from the alignment of resources to customer requirements and experiences. Croom (2001) has examined strategic alignment between a customer and its suppliers, noting that misalignment frequently arises from poor communications and low trust. He further examined the role of customer–supplier (dyadic) alignment in driving shared innovation between the parties. Slack and Lewis (2011) discuss strategic alignment between one organization's operations and its market requirements as a process of ‘reconciliation’ between the two parties' often diverse objectives and requirements.

CovPressWorks, founded in 1890 in Coventry, UK, is a long-time supplier to Jaguar Cars of pressed steel components such as petrol (gas) tanks. For much of the company's history it was a typical ‘metal bashing’ operation, content to build products to customer specifications as well as offer a range of its own proprietary products.

In the early 1990s the company found that its main automotive customers were increasingly demanding it developed its operations processes to provide more synchronized deliveries, employed lean processes and engaged with the workforce in kaizen practices to drive continuous improvements. Perhaps the most significant strategic shift was the expectation that suppliers should increasingly shoulder responsibility for new product development, collaborating with their customer's engineering design team and at the same time taking on what is known as system supply, requiring delivery of complete gas tank assemblies. This meant not only taking responsibility for the pressed steel operations but incorporating the assembly of all valves, pumps, gauges, electronic components and pipework required for the completed assembly. CovPress invested in a dedicated clean room, which was a significant change from its traditional presswork operations.

“We could see significant business opportunities even though they were some way in the future as we had a very steep learning curve when we moved into assembly rather than our usual press and weld operation. What convinced us was, I guess, Jaguar's commitment to the move to system supply and the higher level of assembly we needed to employ, whilst we also saw a radical shift in their supplier strategies. It is fair to say that for years we had been too focused on the regular pricing battles we had with their purchasing department (and they with us). What changed was they really reached out to us to take ownership for the whole assembly, and have a major design input.

Contractually I think we felt fairly comfortable, but it was the really positive attitudes from the top down all the way to the expeditors that made us feel so good about this move. And here we are, 20 years later, with a radically different business, a broader product portfolio and, I have to say, really great relationships with the buyers. They wanted us to focus on building a cross-functional team to serve them, and we decided that we needed to adopt a strategic account management approach. That's how I ended up moving from the shop floor to management, though I do seem to still spend half my life with the operations and pressing guys.”

Gary Mason, Strategic Account Manager and former foreman

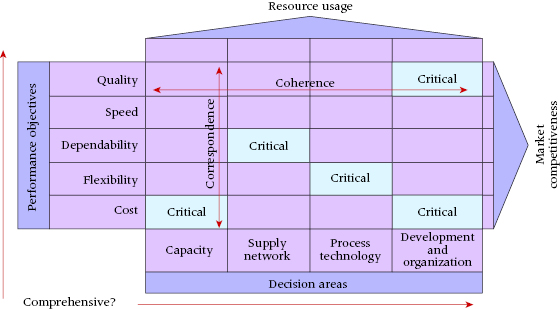

In building a coherent strategic alignment at an operational level between supplier and customer, Slack and Lewis's Strategy Matrix (2011) model has provided a very useful framework for the strategic design of alignment between supplier processes and customer requirements, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Slack and Lewis's Strategy Matrix

Source: Slack and Lewis (2002, 2008)

Note: Reproduced with the kind permission of Pearson Education, from Operations Strategy 3rd edition by Slack and Lewis, ISBN 978-0-273-69519-6. Copyright Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2002, 2008.

This framework connects customer requirements (which are classified in terms of five generic objectives of cost, flexibility, dependability, speed and quality) to the core supply decision areas of capacity, supply network design, technology and development. The core premise here is that decisions relating to improvements and investments in an area such as capacity (i.e. the size, scope and location of process resources) must align to the requirements of the customer. For example, if customers are demanding low-cost supply then decisions about location and economies of scale must support low-cost supply.

Slack and Lewis also highlight the importance of logical consistency when taking supply strategy decisions. There needs to be alignment of decisions to each specific objective (coherence), decisions in any aspect of the operation (such as technology) must reflect or correspond to the ranking of performance priorities, and such strategies must be complete (comprehensive). While this sounds trivial, often there are significant misalignments and confusions in dyadic relations. Buyers and suppliers have different priorities for the same supply process, have confusion between measures and a lack of consistency with their respective organizations. It is vital to overcome these disconnects and gaps, since they are extremely common, as Case Example 7 illustrates.

“We decided to survey our suppliers to find out precisely what they thought our priorities were for them. It was a sobering experience. Fair enough to say hardly any of our suppliers understood our requirements as clearly as we thought they could. It was obvious we were doing a lousy job of communicating both internally but especially with our suppliers. So, we brought them all together for a couple of days' workshop with our buyers, engineers and product managers. Only then did the penny really drop that we had a major task on our hands to really clarify for ourselves what were the ‘right’ objectives and how to achieve them in collaboration with our suppliers.

Quite a few of our suppliers seemed wary of asking us too many probing questions in case we thought any less of them, yet we also had suppliers who clearly believed it was ‘their way or the highway’, so we couldn't just take one approach when trying to align ourselves and our key suppliers. After all, not all suppliers are equal, and not all customers are, so it now seems.

We also found that our view of the suppliers' performance was at odds with how they thought they performed. Sometimes it was as simple as using different reference points – schedule and delivery dates, for example. We would measure response in terms of how long from our signal the supplier took to deliver; they would measure against scheduled date. Neither is wrong, just different. We also found that our own production team had a worse view of delivery performance simply because they did not focus on when goods arrived, just when they got to the production line. Our own internal logistics performance was conflated with supplier delivery, confusing the data point.”

Garry McMann, Purchasing Director

One of the most insightful ways to investigate alignment/misalignment between buyers and their suppliers has been to conduct a series of interviews and surveys across the two parties' operations, sales, marketing and service departments. Using a structured approach to obtain responses about the supplier's view of customer needs and the customer's views of supplier performance helps to provide a valuable insight into the potential for ‘gaps’ in understanding and communication between the parties. Croom et al. (2014) studied 3,600 respondents, analysing the degree of consensus between supply chain partners about customer needs and improvement priorities. A statistically significant gap was found between the respondents in terms of the alignment of key performance criteria and the known demands of customers – in essence a cognitive dissonance where the customer's priorities are known but often ignored.

Illustrating this while also providing a useful framework for analysing misalignment, Slack et al. (2001) developed the notion of a gap model in the 1990s to illustrate the possible sources of misalignment and to highlight precisely where such gaps arise – see Figure 5.

Figure 5 Perception gaps in supply chains

Source: Slack and Lewis (2002, 2008)

Note: Reproduced with the kind permission of Pearson Education, from Operations Strategy 3rd edition by Slack and Lewis, ISBN 978-0-273-69519-6. Copyright Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2002, 2008.

From an operational perspective, buyers increasingly focus on the value of data for measuring supplier performance, yet find that there are significant relationship issues associated with gaining a clear, accurate and relevant view of their performance. In fact, Cousins et al. (2008) found that ‘monitoring supplier performance is not of itself sufficient, rather, it is the process of socializing the buyer and supplier that is critical to success’. Previously, Yorke (1984) had commented that ‘if objectives are to be met in both the short and the longer terms, dimensions for a strategic portfolio should be market- or customer-oriented and not based solely on the perceptions of the supplier's own management thinking, even though it claims to be outward looking to the marketplace’.

How buyers and their supplier relate is thus not a ‘trivial’ issue. The context within which relationships operate has a profound impact on performance, the development of their commercial relationship and the strategic value added through the (buyer–supplier) dyad. The perceptions of the actors involved in the relationship thus have a primacy in shaping decisions and consequently directing sourcing decisions and innovation. How trust is built within the relationship also has a significant impact on the contribution to be gained from the relationship. It is self-evident that engagement with key accounts will involve clearly defining current and expected performance. It is also clear that just asking a buyer is not necessarily sufficient. Buyer–supplier interactions involve multiple touchpoints (Gadde and Snehota 2000) and bringing together the key actors in the relationship, soliciting their involvement and clarifying and agreeing on critical metrics and measures offers a valuable way to reduce the expectation and perception ‘gaps’ in the relationship. This helps to identify how your customer views you, and shapes how you view your customer.

Power-based relationships

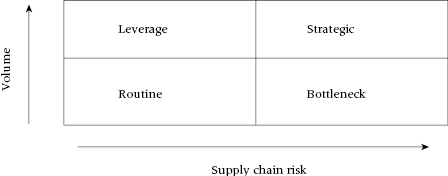

For purchasing professionals, Peter Kraljic's 1983 purchasing portfolio is still regarded as the seminal framework for supplier positioning and segmentation (see Figure 6). It is used to help define the measures for managing each form of relationship based upon two criteria: the levels of supply market risk being faced in each category and the potential financial impact of that category of purchases to overall business performance.

Figure 6 Kraljic's purchasing portfolio matrix

Kraljic's thesis is that one should adopt different strategies depending on the impact and risk faced with a supplier. For items that have a major impact financially (i.e. they are a large-expenditure item) and where there is medium risk in the supply market, he recommends an exploitative strategy; where buyers' strength is low relative to that of suppliers, he recommends efforts to diversify or seek alternative sources. It is common to find that sourcing and supplier management strategies utilize the Kraljic matrix to define the position of individual suppliers and/or categories. However, there are some significant concerns with this one-sided approach.

Zolkiewski and Turnbull (2002) reviewed the literature on customer relationship and supplier relationship portfolio analyses, concluding that many existing approaches are too simplistic, do not take into account the interactions between the different members of the relationship and often focus on attributes that are difficult to evaluate (including profitability potential of a relationship).

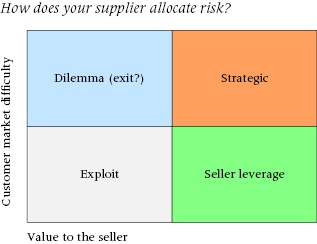

Considering a typical customer portfolio approach which takes the common dimensions of financial return and risk (Zolkiewski and Turnbull 2002), Figure 7 illustrates how suppliers view their customer portfolio utilizing high market risk and high return to categorize their accounts and identify their potential. Almost by definition, suppliers and customers view their relationships as having different opportunities for ‘leverage’ or exploitation.

Figure 7 Typical supplier's risk matrix

The GenCo case (Case Example 8) illustrates a common dilemma in buyer–seller relationships. If a supplier is very important to the customer, is that view reciprocated? If a buyer wants to exploit a particular supplier, as Kraljic claims, what if the supplier really does not view the buyer as important? In other words, buyer–seller relationship behaviours are determined by both sides of the relationship. In the majority of the literature (as Zolkiewski and Turnbull (2002) noted), researchers have failed to consider the relationship from the viewpoint of all those within that relationship.

GenCo Supplies is an MRO (maintenance, repair and operating, or indirect) supplier serving major manufacturing and assembly operations for its customers in southern California. The company sells tooling, steel bar, sheet metal, welding supplies and ancillary components for a wide range of medium- to high-volume customers.

One of the company's major initiatives in 2011 was to reassess its strategic accounts. It had five customers it classed as strategic, and ten more that were ‘important’. Under guidance from an outside consultant, GenCo decided to enrich its classification of its customers by including strategic dimensions such as ‘ease of interaction’, delivery performance/service levels, per annum growth, technological advantage and reputational benefits in addition to the typical measures of volume, turnover and contribution. This led to it reclassifying its customer base into six strategic accounts (of which two were newly classified as strategic, replacing one customer ‘relegated’ out of the classification) and seven ‘important customers’.

“We realized that whilst we thought that our biggest customers should be our strategic accounts, they didn't all offer strategic opportunities for us. One in particular just happened to be a large global corporation with a big spend, but really didn't offer us many avenues to develop competencies we thought would be strategically valuable to us. Plus, they could be really difficult at times.”

Andrew Cozimel, Strategic Account Director

The consultant then spent time talking with each of the strategic and important accounts, focusing first on their buying department and then on their operations department.

“I found that GenCo had failed to realize that they were an important source for one of their customers. The more I talked to everyone involved in that dyad, the clearer it became that there was ‘something there between them’. What really impressed GenCo with our approach was that we had taken into account the views and opinions of both sides of the relationship. Just having the conversation seems to have been a real catalyst for some interesting account relationship developments.”

Jimmy Callahan, Supply Chain Consultant

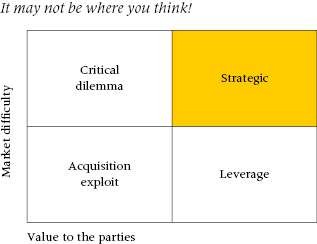

Figure 8 highlights one of the common dilemmas within dyads where there is high volatility yet high potential return. If both parties view the other as ‘strategic’, does that mean they will build a collaborative relationship? Almost by definition, where both parties are attracted to each other there is a strong possibility that there will be mutual desire for partnership. However, the remaining three quadrants present some real dilemmas for one or other party. What if I feel I can ‘exploit’ you, yet you do not view me as significant? Efforts on my part to ‘tighten the screw’ may simply result in you exiting from the relationship (Helper 1993). It can thus be extremely difficult to build a strategic relationship when you have far less power than the other party.

Figure 8 The dyadic relationship dilemma

For this reason, purchasers are increasingly recognizing that they not only want to have strategic suppliers in order to build long-term value but they also want to be preferred customers, opening up the willingness of suppliers to work closely over the long term in a tight, collaborative and innovative manner.

Collaborative innovation

Joseph Schumpeter coined the term creative destruction to describe the economic impact of replacing existing products and processes with new ones. His work was based in part on the notion of Kondratieff cycles – the long-wave economic cycles characterized by technological shifts such as the advent of digital communications and media. The seminal work on sources of innovation has been that of Von Hippel (1978, 1985, 1986), in which he concluded that the process of product development is an interactive process between manufacturers and users. He hypothesizes that two different paradigms describe the generation of new ideas: the manufacturer active paradigm (MAP) and the customer active paradigm (CAP). Simply put, the first paradigm sees new products emerging from the innovative endeavour of the manufacturer, while in the second paradigm the customer identifies ideas and chooses the means of development. In his later works of 1985 and 1986, Von Hippel discusses the notion of lead users as customers who are the main drivers of particular innovative efforts. In other words, not every customer is going to be a dominant innovator in the marketplace, and thus innovation by manufacturers may in fact be strongly determined by the activities of one or two customers.

Foxall (1986, pp. 23–24) contended that in fact there is not a simple dichotomy between CAP and MAP and he later (with Johnston 1987) further extended this perspective by identifying five sources of innovation between the extremes of manufacturer-led to user-led, shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Foxall and Johnston's locus of responsibility for product development (1987)

| Manufacturer-initiated innovation (MII) | Manufacturer performs all stages in the new product development process (Von Hippel's MAP) |

| User-initiated innovation 1 (UII1) | User develops new product for internal use |

| User-initiated innovation 2 (UII2) | The user-initiator approaches manufacturer with innovation for manufacturer to supply (Von Hippel's CAP) |

| User-initiated innovation 3 (UII3) | In addition to UII2, user commercially exploits the innovation |

| User-initiated innovation 4 (UII4) | User is responsible for all stages in the development process, including consumption |

Recognizing that responsibility for the exploration and exploitation of innovation may occur in a number of ways, involving varying degrees of interaction between customer and supplier, raises a fundamental question: how do the various collaborative forms of innovation occur? Von Hippel (1978) claimed that the clarity of customer need and the accessibility of the supplier to the new product activity constituted the determining factors.

Addressing this point, Asanuma (1989) offers a useful categorization of suppliers in which he posits that the extent to which suppliers contribute to the development of new products can be considered in terms of their ‘degree of technological initiative’ (which is much the same as Von Hippel's view that a manufacturer's accessibility is important). Asanuma contends that the approach employed is determined by the characteristics of the origin of product or component being supplied. He observed that Japanese auto manufacturers had three broad types of product: those for which the customer provided the full specification, those parts which the supplier specified and the customer approved, and components which were proprietary, which he called ‘marketed goods’.

Bititci et al. (2004) examined a range of innovative networks and contrasted the structures they found – essentially highlighting the different forms of collaboration between partners in the supply chain and the role of suppliers and buyers in supply chain innovation. Lewis (1990) also examined collaborative alliances and explicitly highlighted the value of trust-based relationships in driving innovation. Many of the examples he drew upon were large, Fortune 500 corporations such as Procter & Gamble, GE, IBM (Owen et al. 2008), Apple, Sony and Kraft, all of which embrace their suppliers and network partners into their innovation practices.

Greer and Lei (2011) highlight the impact of customer involvement and customer engagement in the process of joint development for innovation – a strong encouragement for buyers and their colleagues to take a lead in such collaboration. Payne et al. (2008) employ service-dominant logic to highlight the impact of strong relationship management of customers, by suppliers, in value creation. Whichever way you look at it, collaborative innovation is seen to be a world-class practice.

During the 1990s, we conducted a longitudinal study into the introduction of supplier involvement in new product development at Jaguar Cars in the UK. Over the course of the two years of the Jaguar XJ8 development programme and a similar timescale for subsequent X-type development, we observed the development programme's evolution. We participated in an extensive series of interviews with suppliers, engineers, buyers, product managers, programme managers and production managers with the primary purpose of examining the collaborative nature of the vehicles' development.

Prior to Ford's purchase of Jaguar in 1991, new vehicle development was the province of Jaguar's engineering functions. Suppliers were invited to respond to designs, with no guarantee of any contractual involvement upon launch and subsequent production runs. Indeed, the company had a practice of using prototype suppliers for the development process and using production suppliers only after competitive tendering for the pre-launch and production supply. One consequence of this was that the development of Jaguar's XJS model had taken more than 12 years and had continued to encounter quality and design problems throughout its life. The XJ8 was very different for Jaguar – suppliers became involved at the concept stage, participated actively in the development programme and had a powerful voice in design issues. Consequently, the programme was extremely successful and was considered a ‘proof of concept’.

“Ford instilled in us the Ford Product Development System where suppliers had a major role to play from day one. We selected suppliers based on capability, rather than price, and had to work very closely with them to make sure we all pulled together. I was sceptical at first because we had always taken a more adversarial approach to our suppliers. But I was delighted that we came in on time, on budget and had one of the highest quality products in the history of the company. And we won the annual Ford Best Program award for our efforts. It was a joy to work this way.”

Paul Stokes, Supply Director, Jaguar Cars Ltd 1997

The transformation of purchasing and supply

Buyers are typically represented as confrontational, hard dealing and tactical individuals focused on getting the cheapest price they can. While this is still a valid stereotype in many companies, there is another side of the profession. These are the buyers and supply managers who understand that no business is an island. They see their role as one that focuses on managing total life cycle costs in order to increase the financial health of their business. They appreciate the critical role that trust-based relationships can play in supporting their strategic goals because they know their suppliers are vital sources of competitive advantage. They can articulate the economic benefits of their supplier relationships. They know that they need a comprehensive strategic approach in order to benefit their supply chains. They can work in a range of relationship situations no matter who appears to hold the power. They want suppliers to share information, knowledge and creativity, and drive innovation in both of their operations. Above all, they want to be preferred customers. In fact, they want to see account strategies that are thorough, value adding and well articulated. They want to deal with account managers who are strategic thinkers, can make things happen in their own business and are focused on joint problem resolution.

In conclusion, the following three quotations appear to capture the changes now making purchasing and supply professionals engage proactively with their suppliers, seek out professional strategic account managers and take major steps towards closer integration of their supply chain partners:

“In order for organizations to maintain a competitive advantage, more focus will be placed on trust building, communication, and joint planning and developments. Dedicated groups of individuals will be charged with handling the strategies of relationships with suppliers and customers.” (Institute for Supply Management, USA)

“Our vision is to obtain best value for AstraZeneca from all its external expenditure by leveraging and linking our resources to fully meet business needs and exploit our suppliers' capabilities.” (Astra Zeneca Purchasing Vision)

“Supplier relationship management is a cornerstone of delivering results from cost-down and cost-out focused initiatives over a sustained period. It is often tempting to pressure for price-down in markets where margins are thin, but this behaviour often has the cost of losing the faith of the supplier when it comes to more radical process-based cost savings. … Those suppliers chosen as business partners will be expected to engage in a series of initiatives to attack cost and process innovate. These activities will be at different degrees of magnitude, but their outcomes will be clustered around improving quality, assuring supply, cost down or cost elimination.” (Mark Day and Scott Lichtenstein, Exploiting the Strategic Power of Supply Management, 2008)

The dynamic purchasing executive seeks out suppliers who can articulate a clear relationship development strategy and have developed a strategic account plan in collaboration with their customers. Buyers know that to deliver great results, they need to have a few strategic suppliers helping drive value across the supply chain. In many ways, purchasers are becoming strategic account managers who just happen to be looking in a different direction up the supply chain.

This article has examined how purchasing executives look at collaboration with key suppliers as a core element of their strategic actions. Understanding the expectations, perceptions and needs of customers is at the heart of strategic account philosophy as a means of obtaining value from the account, but it should also add value for the customer to embrace such strategies. Alignment between buyer and supplier is a concept that seems self-evident, yet it is not a natural state in inter-organizational relationships for such alignment to occur. Efforts by SAM/KAMs to drive strategic alignment will need to look at the precise nature of the customer's needs, wants, processes, strategies and desire for close relationships. Increasingly we are seeing that the literature in both the SAM and purchasing fields views a win–win approach as one of the most effective options for driving innovation, value creation and strategic growth. Like any relationship, business or otherwise, understanding the needs of the other party and recognizing where alignment is beneficial requires a conscious and explicit effort.

Implications for future SAM/KAM research

Three areas for future research from this paper offer complementary streams for SAM/KAM researchers.

One of the dimensions of research in the supply chain management and procurement field is the operational alignment and product/process elements of relational interactions. In our discussion of the economics of trust, it is apparent that a total life cycle approach to collaboration with key accounts is an area worthy of further examination. Financial pressures are never far away in our discussion of strategic account relationships, but for purchasing and supply professionals such issues are typically at the forefront of their concerns. Building strategic supplier relationships naturally focuses on the value-added benefits from such relationships; whether this involves value analysis/value engineering approaches to product and process challenges, TCO (total cost of ownership) analyses or category pricing programmes, such financially driven issues are deserving of further study.

The second theme is that of risk management, contingency planning and risk mitigation, which are particularly intriguing areas for corporations with extensive global supply chains. The incidence of natural and man-made disasters has increased significantly over the last 40 years (Bournay 2007) and supplier involvement in contingency planning offers considerable benefits for SAM/KAM research into risk-assessment methodologies, disaster-response strategies and strategic resource positioning.

The third stream of research would address the increasing reliance on collaborative networks for product, process and market innovation, emphasizing a critical contribution for strategic account management in the innovation field. Both in terms of exploration and exploitation of novel ideas, the role of SAM practices addresses issues of intellectual property (IP) ownership, processes of new product/process/service development and factors driving or inhibiting collaborative partnerships.

Conclusion

The role of purchasing and the tools it employs have changed almost beyond recognition over the last 20 years. Purchasing has undoubtedly ascended to a far more central and strategic role in major corporations, a transformation that will continue to impact on SAM/KAM. In some ways, it might be viewed as a balancing of the power equation, but it is much richer than this. Purchasers have long been regarded as the tough negotiators, squeezing every last cent out of suppliers. That undoubtedly is going to continue, but a significant shift towards value- rather than cost-focused supplier negotiations and supplier management offers immense opportunities.

We are seeing the agenda move towards the benefits of collaborative innovation, supplier-led improvements and joint strategies for adding value to the end customer while enhancing return on investment. Procter & Gamble is probably one of the world's leaders at capitalizing on supplier innovation. It exemplifies the strategic value of looking outside its four walls for new products, new processes and new markets. This mirrors the aspirations of strategic account managers. Building business on price is never seen as a sustainable or desirable strategy, yet frustratingly has been the scene too often faced when interacting with purchase agents. As purchasing moves to a more central and strategic role, a common ground is emerging for both parties to focus on common goals, a clear plan for engagement and a mutual respect between transacting parties as they move towards longer-term and fruitful partnerships.

Notes

1 See both the Institute for Supply Management, USA and the Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply, UK.

2 World Trade Organization and Institute of Developing Economies (2011) Trade patterns and global value chains in East Asia: From trade in goods to trade in tasks. Geneva and Tokyo.