4

IDENTIFYING AND OVERCOMING ORGANIZATIONAL INNOVATION CONSTRAINTS

Katharina Hölzle

University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

Tanja Reimer

Europe University of Flensburg, Flensburg, Germany

Hans Georg Gemünden

BI Norwegian Business School, Oslo, Norway

Introduction

As identified in Chapter 1, innovation challenges can be thought of as barriers, failures, or constraints. In order to control and take appropriate actions to overcome organizational innovation constraints, it is necessary to be able to identify them. In this chapter, we provide an approach to systematically identify symptoms and causes of organizational constraints. We also present one solution approach for training and enabling employees how to overcome organizational constraints: the “Innovation Think Tank.” In this chapter, we categorize and explain four different innovation constraints that we have identified in our research. Details about our research are presented in “About Our Research.”

4.1 Systematic Identification of Organizational Innovation Constraints

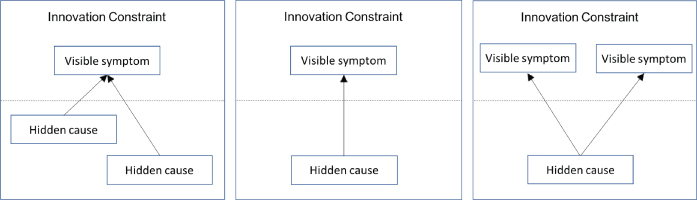

In the literature, various factors are described as organizational constraints to innovation although they might either be the triggers or the effects of a true constraint. We therefore start with a multidimensional concept for innovation constraints. An innovation constraint can be characterized by a visible symptom and its underlying (often hidden) cause. The symptom is usually easily observed and manifests in arguments against pursuing a particular innovation project (e.g. high development costs, uncertain sales). Constraint symptoms are triggered by hidden causes such as misdirected resources or insufficient knowledge. By combining the symptom and its cause(s), innovation constraints can not only be better identified but also can be more clearly explained with a manageable number of symptoms and causes.

As Figure 4.1 shows, it is possible for an innovation constraint to have several causes that together lead to a symptom that is visible and recognized by members of the organization. The combination of the cause(s) with the symptom is the innovation constraint. A useful analogy for this is the medical field. A patient shows identifiable symptoms of an illness (limping) that may have multiple causes (sore muscles, broken bones). Causes and symptoms together lead to a constraint (can't go for a run) that hinders the patient from pursuing a particular goal (stay or become fit).

Figure 4.1: Structure of an innovation constraint.

Recognizing Innovation Constraint Symptoms

In order to overcome an innovation constraint, we have to tackle the roots of the problem. As these roots are often not or only barely detectable, we need to clearly understand how the constraint is expressed by its symptom(s). When project members and leaders are asked what hinders the optimal course of the innovation development process, they usually have an array of different descriptions (constraints) that must be linked to the respective symptoms in order to understand the underlying causes and tackle them in turn. Next we describe the five main symptoms that we have found in our research. The description of these symptoms will help the reader to diagnose what the problem is. Then we explain some root causes of these symptoms and then discuss solutions to solve the causes in order to overcome the innovation constraint.

The five main symptoms we have found are:

- Lack of internal cooperation

- Lack of external cooperation

- Shortcomings in goal setting

- Lack of adequate infrastructure

- Restriction of innovative action

Lack of Internal Cooperation

Internal cooperation is crucial in the product development process. It includes members of the project team as well as organizational members outside the team with whom team members work. For example, an innovation constraint symptom may be too little communication within the project team or the fact that essential information is not made available to the team by individuals outside of the team. Similarly, a detectable symptom might be the insufficient level of support provided by colleagues within and outside the team. Finally, another visible symptom is that project members must expend a very high level of effort in their immediate work environment. In other words, team members express perceptions that they cannot work satisfactorily with their colleagues.

Lack of External Cooperation

The lack of external cooperation symptom describes problems in the organization's collaboration with suppliers and customers, thus explicitly focusing on the interface of the innovation project with the company's external environment. A detectable symptom can be missing, incomplete, or not shared information or insufficient communication from the external partner. Furthermore, team members express the feeling that involved employees from the supplier's or customer's organization do not support the cooperation or recognize its value.

Shortcomings in Goal Setting

The symptom of shortcomings in goal setting is expressed by uncertainty and disagreement about the project's goals from the involved parties, i.e. management, partners, and project members. It includes uncertainties about the actual problem structure as well as future goals. Often project goals are changed over the course of a project and are not adequately reflected in a change project structure or alignment of the project with its environment. The project might be stopped for an undefined period of time and/or important decisions for continuing the project may not be made. Another frequent problem is caused by changing project objectives that also entail a change in the task within the project framework. Furthermore, unclear responsibilities contribute to a lack of a clear definition of involved internal partners tasks,' responsibilities, and timelines.

Lack of Adequate Infrastructure

The term “lack of adequate infrastructure” for an innovation project refers exclusively to tangible resources, such as personnel, financial resources, and operational resources. A personnel shortage is characterized by inadequate staffing with professional staff. A financial shortage prevents, for example, the purchase of materials or machines. In regard to operational resources, unsuitability of existing equipment and software slows down the development work. Another crucial point is the support of project members through deliverables from outside of the project, such as construction and prototypes. This deficiency is outside the project team's area of responsibility and inhibits the progress of the project due to exceeding time limits or insufficient quality.

Restriction of Innovative Action

The restriction of innovative action symptom describes the lack of individual capacities identified by the innovators themselves. This means that innovators within the project do not have enough time to get involved in their innovation project. The symptom is visible in the fact that employees cannot fulfill their project tasks due to insufficient capacities or cannot develop new ideas freely. Hence the creative potential of the innovators cannot be fully exploited, which ultimately has a negative impact on the innovative nature of the project. Again, this symptom is the individual-perceived deficit of his or her own resources.

Understanding the Causes of Innovation Constraint

The symptoms just described can be triggered by one or more causes. In our research, the respondents gave us at least one cause for every symptom. From the perspective of the people involved in the innovation process, there are four main causes of innovation constraints:

- Lack of skills

- Lack of motivation

- Strategic restrictions

- Operational restrictions

We would like to point out that these are the causes that our respondents perceived. Although some causes obviously have some deeper and far-reaching reasons, we have decided to stay on this level of explanation because these were the causes respondents associated with each symptom. This is important as these perceived causes need to be remedied and addressed in the eyes of the project team. Even if there are broader structural causes at play (and upper management should of course address these), the perceptions of team members is critical for recognizing and then actively overcoming the constraint.

Lack of Skills

Lack of skills means that the existing knowledge at the company is not sufficient to solve the tasks at hand. This is due to the fact that either the individual and/or the organization lacks the knowledge to carry out the tasks of the innovation project. Organizational knowledge is missing if individual knowledge is not available and/or successfully transformed into organizational knowledge. The know-how and experience required for the innovation can also be missing in the company if projects are outside the core competencies of a particular department or if the innovation concept has been developed outside the company and the necessary skills are not available in the organization are not available. Furthermore, often innovation projects are associated with very high technical requirements and, depending on the state of knowledge, high to very high decision-making risks. While a lack of skills can be associated with a not-well-planned human resources policy or shortcomings in the hiring process, this is a rather long-term aspect of human resource planning that we have not been addressing with this research.

Lack of Motivation

Lack of motivation describes the individual rejection of the innovation project. To be innovative, individuals need to be willing to spend time on and be dedicated to the innovation project and have a certain risk tolerance for it. A lack of motivation leads to an insufficient willingness to support the innovation; in its enhanced form, lack of motivation can even lead to active action and conscious decisions against the innovation. Furthermore, risk-averse behavior – i.e. the lack of willingness to take an increased risk and an adherence to known experiences – is particularly restrictive, since it is associated with the lack of motivation to learn new and to change habitual behaviors. Individuals need an intrinsic drive for change to become innovative and to actively support innovation. However, if they have had prior bad experiences with innovation, their motivation for engaging in innovative behavior will be rather low.

Strategic Restrictions

Strategic restrictions occur when the strategic direction of the company or a department is not consistent with the objectives of the innovation project. This can lead to conflicts if departments are overloaded or if overlapping areas of responsibilities lead to competency disputes. Furthermore, unclear task guidelines and poor project support delay the development progress. Often an innovation is desired but will be accepted only if innovators prefinance the project out of their own departmental budgets. Unclear decision-making powers are manifested by restricted access to external information, either because a third party is intervening or due to restrictive guidelines of the company. Furthermore, if project managers have a low degree of autonomy, they will also not be able to make decisions needed for the project. This is particularly evident if the relationship between the line and the project is not clearly defined or if the matrix organization is not correctly set up.

Operational Restrictions

Operational restrictions occur when strongly formalized or inflexible processes hinder the project. These routines are mostly set up to facilitate day-to-day operations and to perform standard tasks effectively and efficiently. They can make innovation easier if they leave room for flexibility and change but can hinder projects if they are too formalized. However, the other extreme is also possible: that there are no defined processes or only internal information flows. Spatial separation of project teams or inadequate organizational knowledge management leads to undefined internal information paths. In terms of personnel policy, high employee fluctuation and the distribution of employees on too many different projects poses problems for the progress of innovation.

Dealing with Organizational Innovation Constraints: Symptom-Cause Combinations

The five symptoms and four causes can be combined in a variety of ways. As a result, there are theoretically 20 possible types for innovation constraints; however, all do not occur with high frequency. For this chapter, we focus on three innovation constraints we have found most often in our research. In the following sections, we describe these three constraints in detail by the specific manifestations of their symptoms and causes. We furthermore elaborate on organizational limitations that further enhance the innovation constraint and provide some best practices from our research for the adaptation of the innovation process (i.e. how to overcome the innovation constraint).

No Freedom for Innovative Thinking (“I Have a Dream”)

In many organizations, there is no time or freedom to think outside the box or to try things out. Often employees feel that, although they are required to be creative and innovative, this is neither enabled nor rewarded. In particular, the goal-oriented achievement of project goals is rated higher than the elaboration of truly novel solutions. When project members are working to the limit of their ability in fulfilling day-to-day tasks, they no longer have the intellectual capacity to develop new ideas for innovative solutions. Furthermore, the lack of temporal freedom leads to incremental improvement and suboptimal solutions in current and future projects due to constant time pressure. Besides the operational restrictions, we also observe that a lack of motivation leads to a restriction of innovative action, as some employees told us that they tried to propose new ideas or improvements in the past and were either laughed at or were in other ways negatively associated with their “dream.” And last but not least, a lack of skills and methods with respect to how to think creatively, how to take different perspectives, or how to communicate these often fuzzy ideas adequately were also identified as causes of a lack of innovative action.

Adaptation. In order to enable employees to develop innovative solutions with sufficient time and intensity, they have to be given freedom outside their day-to-day work. This freedom can be promoted by a temporary spatial separation from their workplace and/or by a methodological support of the employees. From the very beginning of the innovation project, freedom for creativity needs to be encouraged and integrated in the project plan. This means less formalism in the early stages of the innovation and a basic understanding of all participants for the innovation process and its implications. Project management must be designed based on the size of the project; i.e. reporting procedures should be reduced to a basic level where true value is created and the procedures should be considered in project planning and controlling. Furthermore, a fixed percentage of working hours could be assigned to scouting or project-relevant studies. Working in a designated space – e.g. an Innovation Think Tank – also helps project members to get in a “thinking and doing mode” that fosters creativity and innovation. Some organizations train their project teams in using creativity methods and provide external support for literature and patent research. Overall, we have found that providing designated time-outs from the operational project work and offering team members dedicated freedom for innovative thinking outside of their regular work environment helps to overcome the constraint of not enough innovative thinking. This can be done through, for example, one- to two-day Design Thinking or creativity workshops led by experts in creativity, Design Thinking, or other innovation methods. Scheduling dedicated innovation project days where experts from other departments or units are invited can also help companies look for solutions outside of the box. In later project stages, freedom for innovation can be supported by providing venture capital to develop these ideas further or providing sabbaticals for employees to pursue their ideas for a designated period of time.

Ideas Are Rejected (Being Don Quixote)

Once employees take the initiative to think outside of the box and develop a new idea, often the idea is turned down. Innovative, unfamiliar, or seemingly crazy ideas are rejected or do not get any attention. They are not included in the idea selection or prescreening process as nobody feels responsible for them. As a result, the initiator feels like Don Quixote jousting at windmills and being the only one taking a stand for the idea in order to secure the support of the department or unit on his or her own. Especially for employees who have not been with the department, unit, or organization for long, this is a major innovation constraint. The symptom for this constraint is a shortcoming in goal setting, caused by operational restrictions. While formalities and criteria for the decision-making process play an important role at product development process gates to ensure the comparability and transparency of the innovation process, they are a major obstacle for conceptual ideas as they are not suitable for evaluating them. This is particularly serious in the case of radical innovations. On one hand, such innovations are desired by the company; on the other hand, they do not find a place in the innovation process because they are so novel that they cannot be assessed with standardized criteria and thus fail at the gates.

Adaptation. If the organization is looking for ideas outside the existing business area, it has to create a way to overcome the filter “Fit to existing business or process.” Already in the phase of idea generation, it should be possible to get “homeless” ideas into an idea pool and to enable an initial assessment by experts from different disciplines. In order to develop these ideas further, resources need to be provided centrally, e.g. by a central or cross-divisional research department. Depending on the size of the organization, this might be done through one designated idea scout/promotor or a team. This person/team serves as the “idea police” for radical or crazy ideas and is equipped with its own designated fund to conduct a first assessment of these ideas (involving different experts and/or external stakeholders). In their target agreement, this person/team is responsible for scouting a specific number of radical ideas per year. Furthermore, the organization might want to rethink its product development process and adjust it based on the degree of innovation; thus, shorter, more iterative, flexible, and open process might be used for radical ideas while incremental ideas follow the standard innovation process.

No Support for Innovation Projects (the Nonstarter or “We Don't Do That”)

Even if the idea is evaluated positively and the innovation project is (often with a lot of expectations) kicked off, many projects become nonstarters as they are not sufficiently supported through adequate resources. For example, there is a lack of specialists for specific tasks and development steps in the project or there is a lack of technical support because there is not enough staff (e.g. technicians and designers) available for the project. The lack of financial resources for an innovation project is particularly noticeable in technological innovations. It is often very difficult to get long-term, reliable financing for these types of innovation. The causes for these symptoms can be lack of skills or strategic restrictions. If a company starts too many projects at once because of the fear of missing out on something, in most cases there are not enough available resources. If several innovation projects are running in parallel, experts need to spend their time on various projects, which leads to work overload and conflicts. Here, we often find a lack of coordination of innovation projects across the whole organization (missing innovation portfolio management). In addition, employees are often withdrawn from projects at short notice if a problem occurs in their regular field of work, resulting in a lack of personnel resources for the innovation project. The reason for insufficient long-term financial support for technological innovations is often that such projects are associated with high risks and unknown ends. When a company decides to invest in technological innovation, the commitment has to come from top management. If this is not the case, or if the commitment is only on paper, often the research and development (R&D) department has to cover the necessary expenses from its own budget and cannot sustain the innovation project in the long term, which often leads to abandoning the project on short notice.

Adaptation. It is mandatory to establish overall portfolio management and assign resources accordingly. The company needs to have central innovation portfolio planning to know exactly which projects are planned (in the early stage), which are currently running, in which stage of the innovation process they are, who is assigned on what basis to which project, and what the status of the project is. The innovation portfolio could also include those ideas they have identified with potential but that are currently in the evaluation stage. Furthermore, the planning has to ensure that experts are not allocated to too many projects at once. Personnel fluctuation and skill development need to be considered. And last but not least, the company needs to let all project team members know what comes after the current project so they don't spend time looking for the next project while the project is still running, which would lead to a lack of commitment and motivation.

If promising ideas are identified and the exact amount of resources needed is not known up front, sufficient funds and resources need to be assigned for longer than the expected project duration and permanently allocated to the project so that they cannot be withdrawn on a short-term basis. A written contract at the beginning of the innovation project confirms the organizational commitment to the project and increases the hurdles to shift resources. With respect to technological innovations, the company needs to be aware that these innovations are usually not one- to two-year commitments but rather long-term ones that need different criteria for evaluation and management of the innovation process than, for example, incremental product innovations. Providing a shared space where experts can gather to give feedback to several projects at specific times (as e.g. in the Innovation Think Tank; see Section 4.2) allows for better exploitation of scare resources.

In summary, these three examples have shown the structure of innovation challenges, consisting of observable symptom(s) and their underlying cause(s), as depicted in Figure 4.1. If the organization or the employee feels that there is an innovation constraint, the diagnostic instruments described in this chapter can help to separate the symptom from the cause. Our examples show how the constraint manifests itself and can be overcome using one or more of the described adaptations. In the next section, we present a best practice that we have developed, prototyped, tested, and evaluated together with one of our corporate partners. Many of the individual adaptation options are combined in the concept of the Innovation Think Tank.

4.2 Overcoming Innovation Constraints: The Innovation Think Tank

At one of our corporate partners, we repeatedly found two innovation constraints: no freedom for innovative thinking and no support for innovation projects. Although the organization itself is a highly innovative and technology-oriented company that praises itself for its technical and engineering competence, the employees expressed their concerns about major constraints especially in the early phases of the product development process. They felt that they not only lacked time to push the early stage of R&D projects, but they also had problems to keep a clear head for these tasks when working long hours on daily business. Furthermore, they often found that they could not get an expert's opinion on short notice because there was no project contracting due to the small size of the activities and other departments would not allow their experts to join the project. Based on our classifications and the proposed adaptations, we developed and tested the concept of an Innovation Think Tank in order to overcome the constraints of the early phase of innovation projects. The Innovation Think Tank is a space within this company where R&D employees meet to work on early-stage tasks. The Innovation Think Tank supplies them with food for thought and inspiration in order to accomplish their tasks and (early) project goals. Unlike the classic think tank that focuses on a single topic, our concept allows for simultaneous work on different topics. Common to the classic concept is the get-together of experts who help one another. The focus of the Innovation Think Tank is on the completion of concept studies (innovation projects in their early phases). Hence the Innovation Think Tank also helps to balance the importance of the early and late stages of innovation projects within the organization.

Elements of the Innovation Think Tank

The Innovation Think Tank prototype consists of four elements:

- Space design

- Structure of work and time

- Effective learning

- Networking

Space Design

The design of the Innovation Think Tank aims to provide an alternative working environment that is creativity-enhancing. Vitally important is the physical separation from the daily workplace. To meet the special requirements of early-stage tasks, it is important to create a calm and undisturbed workplace (positive isolation effect). Single-user workstations allow for independent and individual research and work. A physically separate room for intensive discussions or conference calls is available. A coffee area, a place for expert group discussions, and an information area (with access to scientific literature) are also included in the think tank.

Structure of Work and Time

The structure of work and time is flexible. The attendance at the Innovation Think Tank is voluntary. Participants are, however, requested to work on a specific and already planned task. The Innovation Think Tank was open for four weeks (starting at 8 a.m.) and employees could freely choose their time slot, though they were asked to use the Innovation Think Tank for several days with a minimum of four hours per day. The flexible structuring of work and time led to different group compositions and fostered creativity-enhancing exchange of information. A joint kick-off session every day (10–10:30) was the only compulsory interruption of the workday. Participation at expert discussions that usually took place at one o'clock was voluntary. In order to keep day-to-day business away from the Innovation Think Tank, participants were asked not to be accessible via mail and telephone to the greatest possible extent while they were using the think tank.

Effective Learning

Effective learning is reached through the systematic finishing of innovation activities and a support program. Participants experience how they can successfully handle tasks in the early phase of innovation projects. The support program is made up of speeches and expert discussions as well as methodical support concerning literature and patent searches. The methodological support is provided by the corporate information center that delegated one staff member for the term of the Innovation Think Tank (four weeks). Over the course of the four weeks, 15 expert discussions were hosted by nine corporate experts in the field of creativity techniques, technology trends, business segment strategies, and marketing.

Networking

Networking, facilitated by a moderator, is an important element of the Innovation Think Tank as it fosters communication and exchange. Finding a balance between a calm working atmosphere and an active exchange among the R&D employees is a major challenge for running the Innovation Think Tank. To solve this conflict, interpersonal exchanges were particularly promoted during expert discussions and kick-off sessions (where participants were directed to introduce themselves and their topic to the group in five minutes). Next to these directed networking offerings, participants also bonded at the coffee area – in many cases cross-departmental.

Promotion and Execution of the Innovation Think Tank

The offer to use the facilities of the Innovation Think Tank was distributed via corporate intranet. Additionally, department heads were personally informed about the concept and served as multipliers. The test phase of the Innovation Think Tank spanned four weeks and was used by more than 100 R&D employees (60 of them worked on their early-phase innovation tasks; the others attended workshops). In the first week, a simple lunch was provided for everybody interested in visiting the new facilities. The team of the Innovation Think Tank offered tours, brief stand-up workshops, and short exercises. Furthermore, top management specifically addressed middle managers to identify and invite inventors and multipliers to the think tank.

Evaluation of the Innovation Think Tank

The number, length of stay, and behavior of participants were recorded on a daily base. Additionally, the trial run of the Innovation Think Tank was accompanied by a written evaluation (conceptualized by the research team). The evaluation consisted of two parts – initial and final evaluation. The initial evaluation was based on personal interviews about an individual's motivation for participation and expectations. Main drivers for motivation were (i) the search for a calm and undisturbed work area, followed by (ii) the wish to complete the early phase of a current innovation project, (iii) to see what colleagues are working on, (iv) pure curiosity, and (v) the search for support. Participants expected a time reduction until completion of the early phase up to 50%.

The final evaluation looked at the extent to which the individual targets had been reached. Furthermore, improvement of the concept was to be derived from the evaluation of the different elements of the Innovation Think Tank. The vast majority of participants achieved a significant time reduction while working on their projects in the Innovation Think Tank. One participant stated: “It was great. [Our stay in the Innovation Think Tank] effectively reduced the processing time by several months.” Results concerning the work atmosphere in the think tank also showed that the physical separation enabled a more efficient working style. Besides the small number of disruptions, the low noise level and the limited availability by phone were evaluated very favorably. Expert rounds with a strong focus on interaction got positive ratings whereas expert rounds in a “presentation style” were less appreciated. The expert rounds in the fields of patent or literature research and technology trends were valued highly while topics in the field of business segment strategies were considered least useful.

Furthermore, participants expressed their gratitude for having the freedom to “just try things out.” They felt that they could openly express crazy ideas and found support (sometimes from very different departments) to exchange ideas and work on their projects. They also felt that the think tank's team provided valuable input on how to pitch their ideas in subsequent phases to obtain funding and support.

At the beginning of the test phase, the concept of the Innovation Think Tank faced a lot of skepticism in all hierarchical levels. Reluctance was particularly observed at lower and middle management levels. Consequently, the degree of capacity utilization was low during the first two weeks of the testing phase, and true collaboration did not really happen. In the second half of the test phase, the number of participants continuously rose as the Innovation Think Tank became wider known within the company due to the positive feedback of the initial users.

To sum it up, the first prototype of Innovation Think Tank was a success. Results indicate that team members could execute tasks more efficiently and with lower effort compared to their working style outside the Innovation Think Tank. Moreover, the Innovation Think Tank made it possible for participants to work on ideas that usually buried in day-to-day work. Therefore, the Innovation Think Tank could be a good tool to mitigate typical innovation challenges that occur in the early phases of innovation projects.

The positive feedback of the R&D employees who tested the prototype for four weeks provides evidence that a corporate Innovation Think Tank can be a valuable tool for handling innovation challenges, especially in early phases of innovation projects. The Innovation Think Tank is meant to support the execution of pre-studies in a quicker, more cost-efficient, and more innovative way. It provides space, freedom, and support for developing ideas and get first feedback. It aims to enable a better and more intense access to innovation projects in the early phases. Moreover, it provides guidance and support in the forefront of important gate decisions. The testing phase of our prototype revealed that the intended targets have been met. The Innovation Think Tank made it easier for R&D employees to apply successful tactics to overcome organizational constraints leading to innovation challenges: These tactics included intense discussions within the project team, having a designated team space for the innovation project, communication with experts from other teams, and having the freedom to work on alternative concepts.

References

- Mirow, C. (2010). Innovationsbarrieren. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

- Reimer, T. (2014). Umgang mit Innovationsbarrieren – Eine empirische Analyse zum Verhalten von F&E-Mitarbeitern. Hamburg: Verlag Dr. Kovac.

Further Reading

- Amabile, T. and Kramer, S. (2011). The progress principle. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Catmull, E. and Wallace, A. (2014). Creativity, Inc: Overcoming the unseen forces that stand in the way of true inspiration. New York, Random House.

- Dougherty, D. and Hardy, C. (1996). Sustained product innovation in large, mature organizations: overcoming innovation-to-organization problems. Academy of Management Journal 39 (5): 1120–1153.

- Kanter, R. M. (2006). Innovation: The classic traps. Harvard Business Review 84 (11): 73–83.

- Loewe, P. and Dominiquini, J. (2006). Overcoming the barriers to effective innovation. Strategy & Leadership 34 (1): 24–31.

- Wheelright, S. and Clark, K. D. (1992). Revolutionizing Product Development. New York: Free Press.

About the Authors

DR. KATHARINA HÖLZLE, MBA, is a tenured professor and holder of the Chair for Innovation Management and Entrepreneurship at the University of Potsdam in Germany. She is also an Associate Professor at the Hasso Plattner Institute and its School of Design Thinking in Potsdam. She is Editor in Chief of the Creativity and Innovation Management Journal since 2016. She has published various articles in the fields of innovative behavior, business model innovation, project management, and open innovation in leading scholarly and practitioner journals. She holds a PhD from the Technische Universität of Berlin, a diploma in business engineering from the University of Karlsruhe, and an MBA from the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia. In her research, she looks into culture and organization of innovation, barriers to innovation, design thinking, innovation leadership, and digitalization.

DR. TANJA REIMER is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Flensburg in Germany (Dr. Werner Jackstädt-Zentrum für Unternehmertum und Mittelstand). Her research interests are in the field of innovation/entrepreneurship, strategic leadership, and corporate governance. Dr. Reimer obtained her PhD from the Technical University of Berlin, where she also worked as a research assistant (2008–2011) at the Institute of Technology and Innovation Management. From 2012 to 2014 she was a member of the Center for Controlling and Management at the Otto Beisheim School of Management in Vallendar, Germany, and worked on projects about volatility and innovation topics in the field of management accounting.

DR. HANS GEORG GEMÜNDEN held the Chair of Technology and Innovation Management at Technische Universität in Berlin from 2000 to 2015 and is currently Professor of Project Management at the BI - Norwegian Business School. He has published several books and a great number of articles in the field of technology and innovation management, corporate management, organization, marketing, human resource management, and accounting. Professor Gemünden's specific areas of interest currently are the research of radical innovations and innovation networks, service innovations, particularly in the field of telemedicine, entrepreneurship, and strategic project management, as well as lead users and lead markets.