5

NEW SERVICE DEVELOPMENT FOR PROFESSIONAL SERVICES: TIME COMMITMENT AS THE SCARCEST RESOURCE

Floortje Blindenbach-Driessen

Organizing for Innovation LLC, Tyson's Corner, VA, USA

Introduction

Professional service organizations (such as law firms, hospitals, and consultancies) are organizations whose primary asset is a highly educated professional workforce and whose outputs are intangible services encoded with complex knowledge. As a result, these organizations differ significantly from manufacturing firms in their organizational structure, employee composition, and decision-making processes (Von Nordenflycht, 2010). The most valuable asset of professional service organizations is their pool of talented professionals. Given the pivotal role of these professionals in the day-to-day operations and innovation efforts, their time commitment is a scarce resource that significantly impacts the management and organization of new service development.

5.1 The Peculiarities of Innovating in Professional Services

Time Commitment as a Major Constraint

In theory, there are few differences between the development of a service and a product. It is difficult to differentiate between the two, and the process from idea to implementation is similar for both. In practice, however, there are significant differences. In this chapter, I argue that professional service organizations face a unique innovation constraint: i.e. time commitment. Therefore, they need to organize and embed the innovation process differently from the standard approach described in Chapter 1 of this volume. Specifically, professional service organizations require an innovation support function.

The Need for New Service Development

Companies seeking to thrive need to focus both on their current business and prepare for client demands of tomorrow. For most companies, this is a very challenging balancing act in which many ultimately fail, which explains why so few Fortune 500 companies remain on that list for more than 20 years.

In contrast, most of the American top 100 law firms have been in existence for over a century. The Big Four accounting firms were established more than a century ago. With the exception of a few notorious examples, such as Arthur Andersen and Dewey & LeBoeuf, professional services firms were beacons of stability in the past. Now the future of those firms is threatened by changes in technology.

The first, second, and third industrial revolutions, driven respectively by the power of steam, electricity, and information systems, did not bring much change to professional services. Computers introduced electronic record keeping, making the lives of professionals easier. However, computers did not significantly alter the way professionals interacted with their clients until recently. The World Economic Forum labels the current era the fourth industrial revolution, fueled by unprecedented technological change due to artificial intelligence and connectivity. This fourth industrial revolution is disrupting professional services. Take, for instance, the opportunities telehealth offers. Patients can now monitor their own health, make their own differential diagnoses, and interact with specialists anywhere on the globe. In short, the current technological opportunities not only make clients more proficient, they also alter how professionals and clients interact.

The pressure to improve and implement innovative models of professional services is mounting across industries. In healthcare, changes in regulations and demands for better care at lower costs are major driving forces. Accounting and financial services companies are being challenged by technology companies that serve clients faster, better, and cheaper. While demand for change is rising, professional service firms have been struggling to adopt effective and efficient practices to develop new services that address these challenges and opportunities. As McKinsey chairman Dominic Barton stated, “I think we're very good at telling our clients what they should do, what medicine to take. But we don't like taking it ourselves” (Knowledge@Wharton, 2015).

The Key Role of Professionals in the Innovation Process

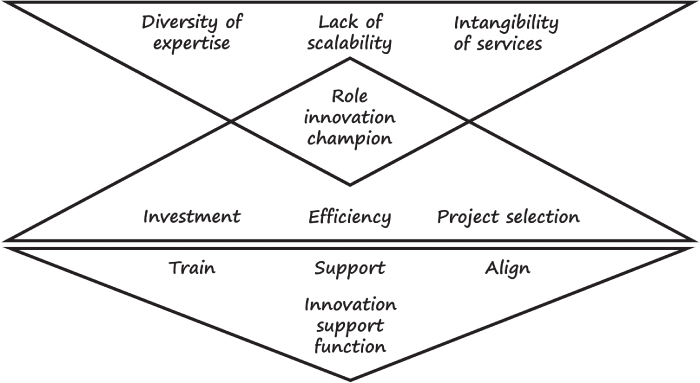

In professional services, the success of new service development efforts depends on the involvement of an expert professional to champion the innovation endeavor. This key role of professionals as innovation champions – as drivers of their innovation projects – is confirmed in several research studies (Anand et al., 2007; Blindenbach-Driessen and van den Ende, 2010). There are three main reasons for this (see also Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1: The key role of innovation champions in professional services.

Diversity of Expertise

Professional services organizations are conglomerates of highly specialized experts. Because of the deep expertise required for new service development, it is almost impossible to adequately staff a dedicated, separate innovation unit. The high cost of service professionals; the need for continually updated, state-of-the-art knowledge (generated by practicing the profession); and the breadth and depth of the expertise domains that need to be covered make such dedicated innovation unit staff choices impracticable.

Lack of Scalability

Most professionals service only a few clients. For that reason, generating substantial returns on investment from any new service is challenging. Consequently, it is important to keep development costs down. Since man-hours are often the largest cost in new service projects, it is important to execute development projects in a timely and efficient manner to minimize the overall investment and ensure that a return can be generated, in spite of the limited scalability.

Intangibility of Services

Professionals deliver intangible services encoded with complex knowledge. This makes it essential for professionals to identify, develop, and implement new services themselves, because it is difficult to transfer this (often tacit) knowledge to others.

Vendors certainly play an important role in the innovation process of professional service organizations. Their products can help providers work more effectively and efficiently. Yet, given the complexity of professional services, even such prepackaged innovative solutions still leave professionals with the task of incorporating these products and technologies into their practices and fitting them into their workflows. As a result, even when technology can be purchased, it requires the time of a professional to turn it into a service offering that clients will value.

In summary, opportunities to innovate are abundant, but professional service providers need to play a pivotal role in the new service development process. Given the challenges just laid out, service professionals are the bottleneck for bringing innovative ideas into practice. Simply stated, most professionals are too busy providing today's services to be able to focus on developing tomorrow's services as innovation champions.

In other words, the organizational context – defined by the diversity of expertise, lack of scalability, and intangibility of services of the professional services – puts top-down pressure on the role of innovation champions. To change the game for their organization or profession, they will have to roll up their sleeves (see Figure 5.1).

5.2 Understanding Time as an Innovation Constraint in Professional Services

Time devoted to new service development does not generate direct revenues, but it does impose opportunity costs. As such, many innovation champions in professional services are under pressure to engage in new service development efforts and make up for the invested time by being more productive in the hours they dedicate to day-to-day operations. This scenario is clearly not sustainable (Kornacki and Silversin, 2015).

Usually when time is discussed in the new product development literature, it concerns time to market – that is, how fast an organization can transform ideas into practical solutions. In the context of this chapter, time constraints relate to the limits on time commitment professionals encounter when engaging in new service development activities.

Certainly, time is a scarce resource anywhere, and time spent on new service development activities never generates immediate revenue. However, time commitment poses special challenges in professional services, because opportunity costs need to be taken into account. Generating revenue and billing hours are key performance indicators for most professionals. While time is money, decision making regarding time and budget allocation in professional services is very different from that in the manufacturing sector. Optimizing for limited available funds is a top-down decision, made by those who have budget ownership and accountability. Optimizing for scarcely available time is a bottom-up decision made by individuals, especially in professional services, where individuals have autonomy over their own actions.

To overcome this time constraint, I start by addressing three intertwined issues:

- Investment. How to stimulate busy professionals to take on dual roles and invest time in delivering today's and tomorrow's revenues successfully and sustainably

- Efficiency. How to develop new services in the most efficient and timely fashion in professional service organizations

- Project selection. How to ensure professionals work on the most promising projects only, eliminate less promising initiatives in a timely manner, and remain aligned with the organization's strategy

In other words, innovation champions efforts face pressure from the bottom up, when investment, efficiency, and project selection are not properly addressed (see Figure 5.1).

Time Investment

It seems paradoxical that in order to alleviate the time-commitment constraint, busy professionals have to invest time and develop new services themselves. Getting professionals to engage in new service development will happen only when there is proof that this time investment actually pays off – in other words, that the rewards are worth the effort and risk both for the innovation champion and the organization.

Historically, when professionals engaged in research or development endeavors, the benefits were for the profession as a whole (e.g. research papers) and the individual (e.g. personal development and reputation). These research projects were funded by various sources, with no clear expectations of a return. However, new service development is geared toward advancing the organization by offering its clients higher-value services. This, in turn, creates a shift in the risk and reward balance from the individual to the organization.

The FISHstep case shows how one legal service professional was able to successfully launch a new service offering. The case illustrates that considerable personal risks were incurred, and substantial investment of personal time was required.

Clearly, Kristal was the driver behind the FISHstep initiative. Less evident is that most of the effort, especially during the proposal phase, was expended outside her professional service hours. In other words, Kristal made a significant personal time investment – time over which the company has no control and for which it provides no payment.

Kristal spent a lot of time acquainting herself with how to write the business case for the initiative. She had not yet been in a leadership position long enough to have experience with the business and management side of running a law firm. Training and guidance in this area could have saved Kristal a lot of time.

While Kristal was successful, few organizations take into account that most new service initiatives fail and don't deliver any tangible results. Simply encouraging participation in new service development activities is thus insufficient to stimulate professionals to invest personal time in these activities.

Failure – or, more accurately, “finding dead ends” – is an intrinsic part of the innovation process. Few organizations cope well with apparent failure. Failure is typically blamed on the team or even more specifically on the team leader. That is problematic.

First, blaming failure on the individual makes it even riskier for employees to stick out their necks and participate in innovation efforts. After all, the chance of success in innovation is small. If failure is blamed on the innovator personally, the consequences of failure will be detrimental to the person's career. This turns investing time in innovation efforts into a career killer instead of a career advancer.

Second, forces beyond the individual leading the innovation effort affect the outcome of a project. The market or technology may not be ready, or the required problem-benefit balance may not exist. In other words, there are often issues beyond the scope of control of anyone involved. Therefore, teams should be lauded for finding out quickly that the opportunity is not worth pursuing further, as this saves the organization time and money while creating room for investments in other, more promising endeavors to advance.

To conclude, to motivate professionals to take on dual roles and invest time in both day-to-day and innovation activities, they need to be helped with the execution of their innovation projects to ensure a return of investment from innovation activities. Time committed to new service development should be spent well and increase the likelihood of success of the project. As most initiatives will not be successful, incentives that encourage participation only are insufficient. With too many initiatives in the pipeline, all efforts are doomed to fail. Instead, incentives should aim to make professionals follow best practices in service development. Best practices are those that speed up execution, help identify and stop less promising endeavors, and only advance the most promising initiatives. At the end of this chapter, I discuss how this can be accomplished with the adaptation of an innovation support function.

Efficiency

Bringing structure to innovation activities is paramount to ensure efficient and effective execution. Innovating in an ad hoc manner (while still common in the professionals services industry [Leiponen, 2006]) is not an effective or efficient way to innovate (Barczak et al., 2009).

Among other factors, an appropriate innovation structure is needed to ensure that the scarcest resource of all – the time commitment of professional service providers – is spent wisely and actually delivers results. This is not a given, because the decisions to commit time are made by individuals, not at the organizational level. Without some overarching structure, there is no way to ensure that the sum is greater than its parts.

The importance of creating an appropriate innovation structure can be illustrated in the healthcare domain. A survey among 121 healthcare providers, including 83 hospitals (as part of the 2015 Institute for Healthcare Improvement annual conference session on innovation management; Trimble et al., 2015) shows that 39% of the participants stated that no innovation infrastructure existed in their organization, and only 12% stated that they had access to a dedicated innovation lab. Given existing and developing healthcare challenges and the ever-increasing demands on clinicians' time, it is surprising how few healthcare organizations have a structured new service development process and structure in place.

It is possible that the lack of structure is due to a persistent myth that structuring an innovation process (such as new service development) limits creativity. Because professionals are used to defining and following their own processes, following a structured innovation process might be challenging. Or perhaps, bringing structure to the process is deemed expensive. Whatever the reasons, having a structured approach is a more effective and efficient way to transform ideas into reality (Barczak et al., 2009).

The George Washington University Telemedicine case illustrates how structure and guidance can help advance new service development in a simple and effective way. The program participants (all full-time working professionals) developed proposals and testable concepts in six weeks. Each participant spent on average three hours per week on the program. In comparison, in most professional service organizations, it takes six to eight months to run an idea up the management chain and 40 to 80 hours to develop a detailed proposal. In other words, by using a structured approach, more was accomplished in less time and resulted in better outcomes.

The telemedicine case shows that by providing structure, training, and coaching, it is possible to guide busy professionals through the new service development process and help them be effective and efficient in their innovation endeavors.

The training, support, and assignments that were part of the system taught the teams how to generate ideas, vet ideas, and validate their own solutions. The structured approach – the exercises that enabled teams to focus on the most relevant topics; the feedback that enabled prioritization of efforts on the weakest and most uncertain aspects; the methodology that forced teams to provide proof for the assumptions underlying their new service concepts – ensured that very little time was wasted. As a result, all the professionals were enabled to combine ideation activities with their full-time jobs.

Two of the four teams realized that pursuing their ideas beyond these six weeks was not worth their time, a finding that shows that when teams are given the opportunity, they are able to evaluate their own progress and likelihood of being successful and are capable of timely stopping unpromising endeavors.

Without a structured approach, bottlenecks that significantly frustrate and hinder the progress of innovation projects are not always recognized for two reasons: (1) because these organizations don't keep track, they don't have the data to identify and address the inefficiencies in their innovation process; and (2) without structure, organizations will not be able to recognize the pattern of failure that may exist or be able to address the cause. An example illustrates this dynamic: In one of the intrapreneurial programs I taught, all the teams faltered about one year into the program. Concurrently, most team leads left the organization, each of them providing a reason for their departure unrelated to their project (e.g. moving because of a spouse's job, moving back to the home country, taking on another job opportunity, etc.). Yet because I was mentoring the teams, I knew that the intellectual property policy of the organization had been tremendously frustrating and hindered the teams' ability to attract collaborators and outside capital. As a result, their promising projects were stuck. Given their ambitions, these talented innovators were not going to sit around and waste their time in an organization that did not truly support their innovation efforts. Had their projects not been frustrated, they probably would have made different personal and career choices. In the absence of success, the organization canceled the intrapreneurial program and failed to address the issues that caused the participating teams to falter.

The innovation support function, as I explain later, is an effective, low-cost solution to execute new service development efficiently in professional service organizations.

Project Selection

To sustain a pipeline of new service development initiatives, rigorous vetting is required so that only the most promising projects are fully supported. Deciding what the most promising projects are in an unbiased and objective manner is a major challenge in any organization, but especially in professional services ones due to typically flat hierarchies and the fact that there are as many specialty areas as there are leaders.

How can these organizations validate and vet projects to ensure that the scarce available resources to execute innovation endeavors are spent only on the most promising projects? The Innovation Institute case illustrates how challenging project selection can be in a professional service organization.

As demonstrated by the Innovation Institute case, without effective ways to select projects, too many projects remain in the pipeline, making new service development a very frustrating process for everyone involved. No project will have sufficient funding to accomplish anything.

In most organizations, a selection committee has the authority and the ability to select and prioritize innovation projects. However, because of the diversity in expertise and the intangibility of the service provided, even the most accomplished and senior professionals lack the insights to vet projects that cover the expertise and domains of all experts in the organization. In addition, while such committees may have a say in how funds are allocated, they typically don't have the authority to dictate how each professional should allocate their time.

The Innovations in Telemedicine course discussed earlier shows that teams can stop unfruitful endeavors in a timely manner. “Timely,” in this context, means not giving up too early or continuing too long. It is in the interest of the innovation champion to stop unpromising initiatives in a timely way, due to the opportunity costs involved. Clearly, stopping unfruitful endeavors is important to prevent clogging of the innovation pipeline. With just a few of the most promising projects in the pipeline, these projects can receive full support and be executed swiftly. Simply relying on self-selection, as showcased in the telemedicine case, however, may not be sufficient. I discuss later in this chapter how the innovation support function can further facilitate project selection.

5.3 Resolving Time as an Innovation Constraint in Professional Services: The Innovation Support Function

Having addressed the three intertwined issues of investment, efficiency, and project selection, it is time to propose a solution that alleviates the time constraint in professional service organizations.

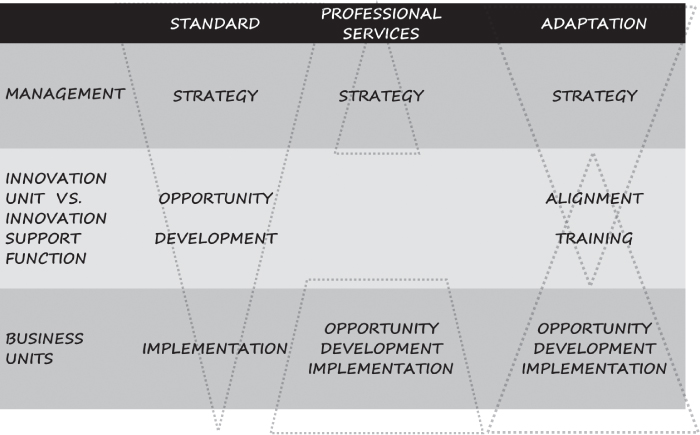

In the standard approach to new product development (see Figure 5.2), management is responsible for defining the strategy. Innovation units are tasked with identifying opportunities and developing an organization's innovation activities to execute upon this strategy. The unit is held accountable for the number of innovation projects in the pipeline, the number of new services introduced in the market, and the success of these new services in terms of revenue and profit. The market introduction and outcomes are often responsibilities shared with the business unit delivering these new services. In other words, an innovation unit executes the innovation process and has the budget, staff, capabilities, and expertise needed to transform ideas into practical applications. Needless to say, setting up such an innovation unit is a costly endeavor due to employee costs, among others. Over time, the results of the innovation efforts should create sufficient return on investment to cover these costs.

Figure 5.2: The standard approach versus the adaptation.

In professional services, management also defines the strategy. However, the standard model to execute on this strategy does not work, because in service firms in general, having an innovation unit in general does not generate more revenues as it does in manufacturing firms (Blindenbach-Driessen and van den Ende, 2014). This lack of result may explain why few service firms have an innovation or research and development unit.

Without an innovation unit, identifying opportunities and acting on them is often left to the business unit or the professionals within the business unit. Without any accountability for development activities, there is a void between the strategic intent of management and the new service development activities that are initiated by professionals and that take place throughout the organization. This was the case for Kristal who developed FISHstep.

The adaptation of the standard innovation process model proposed here includes the following: Instead of having an innovation unit execute innovation activities on behalf of the organization or having no such unit, professional service firms should implement an innovation support function that is responsible for providing support, training, and guidance to the new service development process. It is a support function, because the innovation activities are executed by professionals, which (as discussed earlier) is key to the success of these endeavors.

To ensure efficient and effective execution of new service development activities by these innovation champions, the innovation support function should provide training and coaching. As showcased by the Innovations in Telemedicine course, such training can also help with project selection and is effective in eliminating the least promising endeavors.

Let's contrast responsibilities of the innovation support function with those of a traditional innovation unit. Instead of being accountable for execution, the innovation support function can be held accountable for the courses taught, number of professionals engaged, survival rates or projects, and life span of unsuccessful efforts. Other metrics that are effective in keeping track of the effectiveness and efficiency of the new service development efforts are those that measure the performance of the training program. That is, does the training program provide teams adequate insight in the value and chance of success of the project they are pursuing? Does it help teams focus on the critical activities that support go/no-go decisions? By assessing the results of the training activities in terms of self-selection and average project duration, the innovation unit can support and be held accountable for preserving the scarcest resource in professional service organizations, professional time commitment to new service development activities.

Alleviating the Time Constraint

To innovate successfully, professional service organizations need to engage their busy professionals in the innovation process. Having someone else innovate on their behalf is not effective, because professional services are complex and labor intensive and involve tacit knowledge and expertise. It is difficult to transfer state-of-the-art frontline knowledge and expertise to an innovation unit and have innovation professionals develop novel new services (Leiponen, 2006). Professional services are typically not very scalable either, as they are highly dependent on the service provider. Because of these considerations, it is more practical and economical to engage the workforce in new service development activities than to have a dedicated innovation unit execute these activities (Blindenbach-Driessen and van den Ende 2006, 2014). However, this engagement creates significant constraints on the time commitment of professionals who step forward as innovation champions.

These professionals, who are not skilled or familiar with innovation activities, need to be supported in the innovation task. They need to be able to evaluate which opportunities are worth investing personal time in. These professionals, who are not skilled or familiar with innovation activities, need to be supported in the innovation task. They need to be able to evaluate which opportunities are worth investing personal time in. Providing organizational support to all innovation endeavors brought up in the organization is not feasible or sustainable. There needs to be some form of selection. Putting a lot of money into funding the innovation process is not the solution because, among other reasons, it will be very challenging to recoup these investments due to the limited scalability addressed earlier.

To reduce the burden of time constraints and facilitate efficient and effective execution of new service development projects, the innovation support function must provide structure to the new service development process through alignment and training that delivers:

- Guidance as to which projects to pursue

- Insights that enable teams to self-select more from less promising endeavors

- Actionable data that enables management to identify and prioritize the most promising projects

Getting Started

The innovation support function enables professional service organizations to explore many opportunities yet leaves the organization with just a few, fully vetted projects to support in the more expensive and time-consuming development and implementation phases of the new service development process.

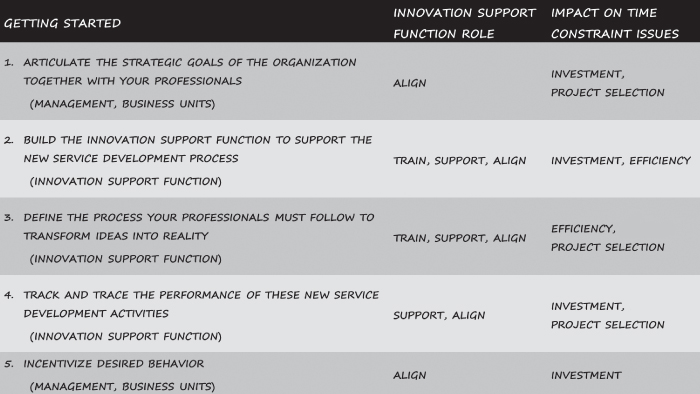

The next five steps will help professional service organizations build their innovation support function. (See Figure 5.3.)

Figure 5.3: Steps to create an innovation support function.

Step 1: Articulate the strategic goals of the organization together with your professionals.

When management – in collaboration with business units – articulates the strategic goals, the objectives of the new service development program become clear. This clarity will motivate professionals to know in which initiatives it will be worthwhile to invest personal time. Articulating the strategic goals also contributes to project selection, as it provides guidance as to which areas to focus on. A law firm shouldn't be interested in 100 projects executed by each of its 100 partners that cover 100 different directions. Instead, it is more valuable for the firm and its clients to gear the innovation efforts toward the same objective, such as being recognized as the leader in Brexit services. Because the firm focuses innovation efforts, interested partners can together figure out how to best help clients who struggle with Brexit-related questions. Such an endeavor, if successful, will benefit all partners, including those not involved in the particular initiative because new services bring in new clients, enable the organization to retain top talent, and increase the innovation capabilities of the organization as a whole.

From Kornacki and Silversin's (2015) work with hospitals, it is clear that telling professionals what to develop rarely works. Quite the contrary, it often results in friction and behavior that undermines the organization's goals. Instead, having physicians and management formulate the strategic mission together creates commitment.

The role of the innovation support function is to facilitate this process of establishing strategic goals by, for example, organizing a strategy alignment workshop. Another role is to make sure that all innovation champions are aware of these strategic goals and can articulate how their projects contribute to achieving them.

Step 2: Build the innovation support function to support the new service development process.

Once the strategic goals are defined, it is clear that someone in the organization needs to orchestrate the process of achieving these goals. As explained earlier, the innovation support function should not be involved in the execution of innovation activities. Instead, it focuses on creating alignment, building support, providing the necessary training to enable the workforce to innovate, and reporting on the progress of the new service development activities.

In this respect, professional service organizations can learn a lot from the entrepreneurial community. No one tells entrepreneurs to start or quit their start-up or how much personal time to invest. Intrinsic motivation drives their behavior. Training programs such as I-Corps provide budding entrepreneurs insight in the efforts necessary to translate their idea into a company (https://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/i-corps/). Such accelerators are effective in terms of time to market and profitability if they provide training, connections, and support for start-ups. The innovation support function should take on the same role as accelerator programs and facilitate the new service development process within the walls of a professional service organization.

The innovation support function is thus truly the support function of the new service development process.

Step 3: Define the process professionals must follow to transform ideas into reality.

The innovation process – from idea generation, development, and implementation to diffusion – is a value chain, with the weakest link determining the overall outcome. In other words, if the organization excels at idea generation but is weak in implementation, the excellence in idea generation is not going to benefit the organization as long as this is not accompanied by the ability to also implement these innovations.

To save time, professionals need to know what process to follow and what expectations there are when they attempt to transform their ideas to practice. The telemedicine example shows how training can be used to provide structure and advance new service development activities efficiently. This example also shows that building feedback mechanisms into the education program enables teams to self-identify and self-select the opportunities that are worth the investment for them and their organization.

The innovation support function is not only responsible for creating, supporting, guiding, and overseeing the innovation process. It is also responsible for training those who partake in this process and providing coaching and other support to advance promising projects. In line with this responsibility is the task to identify and alleviate organizational bottlenecks that hinder innovation projects' progress and that may cause professionals to spend more time on new service development than is strictly necessary.

Step 4: Track and trace the performance of the new service development activities.

New service development activities are to sustain the future revenue stream and profitability of the professional service organization. The innovation support function should develop metrics that show whether the organization is on track. That is, the metrics should show that the ongoing projects enable the organization to reach its strategic goals. Since the innovation support function is not involved in the execution of new service projects, it cannot be held accountable for the success of individual projects.

More suitable metrics to keep track of are therefore related to ensuring that:

- Sufficient projects are initiated;

- Unsuccessful endeavors are stopped in a timely manner;

- Fully supported projects are executed swiftly; and

- The portfolio of innovation activities is sustainable and enables the organization to achieve its strategic goals.

Feedback on project progress, work quality, and team effort will enable teams to compare their projects and team against the pool of projects. Such feedback, as the Innovation in Telemedicine example, makes it possible for teams to self-select and quit mediocre innovation efforts with limited chance of success in a timely manner.

However, just relying on self-selection is not sufficient. Senior management still needs to make a selection among the good and great projects that remain in the pipeline and select a portfolio of projects that is aligned with the organization's strategic goals. By tracking the progress, team effort, and learning of each team in the pipeline, it is possible to compare teams with each other and identify the teams with the highest likelihood of success. These objective metrics make it possible for management to make evidence-based and data-driven decisions, instead of opining about what are potentially good ideas and projects.

Step 5: Incentivize desired behavior.

Although it is important, new service development is rarely as urgent as the daily activities that occupy professionals. Without incentives, professionals will delay or even forget to invest time in new service development activities. With a process, metrics, and the innovation support function in place, incentives can be used to stimulate desired behavior. These incentives should aim to achieve the following:

- Stimulate personal time investment in innovation initiatives.

- Encourage alignment of the innovation activities with the organization's strategy.

- Make quitting of unpromising endeavors in a timely fashion as important as pursuing success.

- Capture lessons learned of failed attempts, as these are often breeding grounds for future successes.

- Ensure that projects are executed as swiftly as possible when given support.

- Promote sharing of the findings and results of successful initiatives with others in the organization to ensure that each successful innovation endeavor delivers a maximum return on investment for the organization and creates benefits for the organization as a whole, not just for the involved professionals.

- Make receiving support for a new service development project a received privilege, awarded to the most talented and dedicated teams only.

By following these five steps, a professional service organization should be able to build an innovation support function that alleviates the time constraint of professionals involved in the innovation process. Successful outcomes motivate professionals to participate. Training and support make it possible to do so. A structured process creates alignment and efficiencies. Metrics enable self-selection and facilitate evidence-based decision making when it comes to selecting and supporting new service development project teams with the highest likelihood of success. This way, even professional service organizations – despite the diversity of expertise, lack of scalability, and the intangibility of their services – are able to bring their ideas to practice in a sustainable and profitable manner.

With an innovation support function in place, professional service firms can also start reaching for more audacious goals. The next step could be productizing the low end of their service offerings, as Legal Zoom, Littler, and Minute Clinics are currently capitalizing on. This low end represents a sizable market share that leading professional service providers of today will permanently lose if they fail to innovate and develop new service offerings.

5.4 Conclusion

The main assets of professional service organizations are their professionals. Their time commitment is the scarcest resource in these organizations. To innovate, professional service organizations will have to commit some of this time to activities that generate new revenue and address future client needs. These innovation projects need to be championed by professionals to be successful. An innovation unit that executes projects on behalf of service professionals will be unable to deliver the desired results because it will lack the critical insights that only service professionals themselves possess, such as expertise diversity, full understanding of intangibility, and recognition of difficulty with scalability of professional services. That is, an innovation unit can create innovative project solutions, but research has shown that the projects do not result in new revenue or additional profits. An innovation support function is therefore a more effective way to assist innovation champions in their dual roles – serving today's and tomorrow's clients. The innovation support function can ensure that innovation projects are worthwhile investments – from both a personal and an organizational perspective; that the innovation process itself is efficient and delivers results; and that performance data is available to select and prioritize the most promising innovation projects. That way, the scarcest resource of professional service organizations – time commitment of their professionals – is invested in the most promising projects only and delivers a maximum return when it comes to innovation and new service development.

References

- Anand, N., Gardner, H. K., and Morris, T. (2007). Knowledge-based innovation: Emergence and embedding of new practice areas in management consulting firms. Academy of Management Journal 50 (2): 406–428.

- Barczak, G., Griffin, A., and Kahn, K. B. (2009). Perspective: Trends and drivers of success in NPD practices: Results of the 2003 PDMA best practices study. Journal of Product Innovation Management 26 (1): 3–23.

- Blindenbach-Driessen, F. and Van den Ende, J (2006). Innovation in project-based firms: The context dependency of success factors. Research Policy 35: 545–561.

- Blindenbach-Driessen, F. and Van Den Ende, J. (2010). Innovation management practices compared: The example of project-based firms. Journal of Product Innovation Management 27 (5): 705–724.

- Blindenbach-Driessen, F. and Van Den Ende, J. (2014). The locus of innovation: The effect of a separate innovation unit on exploration, exploitation, and ambidexterity in manufacturing and service firms. Journal of Product Innovation Management 31 (5): 1089–1105.

- Knowledge@Wharton. http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/mckinseys-dominic-barton-on-leadership-and-his-three-tries-to-make-partner, September 9, 2015.

- Kornacki, M. J. and Silversin, J (2015). Aligning physician-organization expectations to transform ptient care. Chicago, IL: Foundation of the American College of Healthcare Executives.

- Leiponen, A. (2006). Managing knowledge for innovation: The case of business-to-business services. Journal of Product Innovation Management 23: 238–258.

- Trimble, C. et al. (2015). Managing innovation in healthcare organizations. Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 27th Annual National Forum, 6–9 December 2015, Orlando, FL, Sessions D6 and E6.

- Von Nordenflycht, A. (2010). What is a professional service firm? Toward a theory and taxonomy of knowledge-intensive firms. Academy of Management Review 35 (1): 155–174.

About the Author

DR. FLOORTJE BLINDENBACH-DRIESSEN is the Founder of Organizing4Innovation LLC, a company that offers the support and tools professional service organizations need to succeed in their innovation endeavors.

She has assisted professionals with their innovation efforts in engineering firms, system integrators, information technology firms, consultancies, law firms, research centers, healthcare, and entrepreneurship programs. Dr. Blindenbach-Driessen championed many innovation projects while working for the Fluor Corporation and for the Children's National Health System in Washington, DC. She teaches courses related to innovation management and new business development for executive education programs around the globe. Her research focuses on the innovation challenges and opportunities in the professional services and has appeared in Research Policy, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, the Journal of Medical Practice Management, and the Journal of Product Innovation Management.