10

AMBIGUITY AND MISDIRECTION? BRING IT ON! LESSONS ABOUT OVERCOMING FROM WOMEN MARKET TRADERS

José Antonio Rosa

Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA

Shikha Upadhyaya

California State University, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Introduction

A recurring theme in this book is that innovation has many manifestations and that alongside highly publicized breakthrough technologies and magical experiences, hundreds of innovative and yet simple artifacts and processes come to light every day. Equally pervasive ideas are that innovation can arise from unlikely sources and that market and environmental constraints can lead to greater innovation. Constraints force us to adopt and modify current approaches just to overcome them, and they often also elicit hope and persistence that wear away the hindrances. One additional idea, albeit perhaps not as strongly argued in this book, is that creativity under constraints often involves some level of rule breaking on the part of companies and individuals. When socially accepted pathways to market gains are not accessible, rule-breaking solutions are likely to emerge in firms that wish to succeed.

This chapter looks to an unlikely source – women market traders in subsistence marketplaces – for practical insights into innovation under constraints. Examining how women market traders innovatively navigate uncertain and hostile environments, and how they sometimes break rules to take advantage of ambiguity and misdirection in market environments, makes a strong case for companies to allow similar behaviors when business constraints exist and intersect. The constraints these women face – exclusion and sometimes ill treatment on account of gender and social class – are enduring and seemingly immutable in many societies with large, untapped markets. For companies in similarly hostile and unchanging situations, innovative rule breaking may be a means to survival, if not growth. Insights into the functioning of marketplaces in subsistence markets can also help companies that want to serve the 4-billion-strong emerging economy consumer segment. Consultants and business leaders worldwide agree that it is among these 4 billion that most future market growth can be expected. Moreover, bridging the last mile in the producer-to-consumer value chain in subsistence markets presents significant challenge to producers and retailers globally and continues to require the involvement of market traders like those described in this chapter. The practical suggestions presented here will help companies develop low-end innovation capabilities by adding resilience and market responsiveness to that indispensable last-mile distribution support network.

10.1 Innovation and Rule Breaking

The criminal is the creative artist; the detective only the critic.

G. K. Chesterton

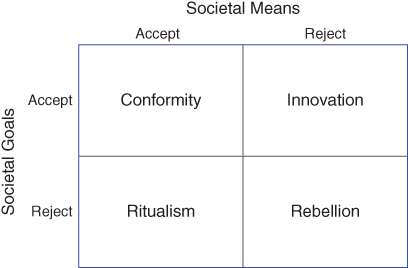

Seeing innovation as violating behavioral norms is intuitively plausible when one stops to consider what is involved. Creativity takes place when existing knowledge is recombined into unusual arrays, and unusual most often means that rules were violated. Children are inherently creative (we call it play) because they are still learning society's rules, and many criminals are creative because they disregard social norms. Sociologist Robert K. Merton (1957) proposed that, in most societies, rules exist about what should be pursued (goals) and how to pursue it (means), and that when people follow rules about goals but disregard rules about means, they are innovative (see Figure 10.1). In general, Merton advocated for societies where goals and means align so people will conform. Modern companies and organizations, however, encourage employees to break rules, or at least some rules, especially in the name of innovation. Many encourage innovation (pursuing company goals through alternative means), and others encourage rebellion (i.e. overthrowing industry and market conventions).

Figure 10.1: Societal goals and means typology.

It can also be argued that tendencies toward innovative rule breaking are easiest to find in social contexts where constraints are most severe, as they typically are in subsistence markets. Prahalad (2006) argued that the poor are an unexplored business opportunity. His perspective was in itself innovative, one that inspired others to look at the poor through different lenses. He illustrated through case studies that poor consumers and merchants are clever because of constraints and life factors that they endure daily. He also proposed that we can learn from the poor about creativity under constraints. This chapter builds on that tradition.

This chapter stems from a large investigative project that has taken us into subsistence markets in India, Colombia, Guatemala, and Fiji, exposing us to dozens of examples of innovation under constraints being carried out by poor people living in subsistence contexts. Some of them involve unique approaches to products such as soaps and hand tools, and others to processes such as hammock weaving and milk retail sales. Innovative rule breaking is amply evident, since in many instances subsistence innovators are involved in raw material reuse and repurposing that people in most developed societies would consider unsafe or unorthodox (e.g. home-crafted hair gel packaged in sandwich bags) and in the continual adjustment of products and processes in response to fast-changing market conditions (e.g. dynamic pricing in response to demand fluctuations throughout the day). Among the poor, innovations have a short half-life because constraints are recurring and their day-to-day implications are unpredictable.

10.2 Constraints Arising from Gender, Social Class, and Their Intersection

This chapter focuses on women market traders, who operate market kiosks and sell door-to-door around the world, and on the gender and social class constraints that they endure and overcome. Gender and social class constraints are inescapable aspects of social identity in all countries and are very much present among the poor. They shape self-image and how others treat us in social encounters. They are also often used by people in power as grounds for exclusion or the withholding of important resources. For women market traders, gender, social class, and their intersection are a continual source of business challenges and hence a trigger for innovation under constraints from which we can learn.

Gender

Gender-based threats and consequences faced by poor women traders are summarized in Table 10.1. The recurring and seemingly unresolvable problem is the inferior status of women in most subsistence societies and how that status impacts marketplace functioning. Because of family needs, low-income women have to contribute to household income while also meeting marriage and parenting responsibilities. When children are ill, it is the woman who tends to their needs without neglecting other duties, such as preparing meals and maintaining a welcoming household for her husband and other family members. The demands are many, and sometimes incompatible, such as when tending the market kiosk conflicts with caring for sick children. Shakuntala (all names are disguised), an Indo-Fijian market trader, exemplifies the daily routines of women market traders in her homeland. Six days per week, she gets up very early (3:00 a.m.), completes daily household chores with no help from family members, travels one hour by bus into the city, sources produce (e.g. jackfruit) from wholesalers before 8:00, works 8–5 in the marketplace, and returns home to cook for the family and complete end-of-day tasks. She goes to bed around 10:00 and starts over in the morning. There are millions of women worldwide just like her.

Table 10.1: Threats women market traders face.

| Threats | Consequences | What companies can do about it |

| Inadequate literacy and numeracy skills | Finances: The women resist joining savings plan that would help them invest better and manage their personal lives. Further, financial decisions are made by older family members or male members, which affirms the women's lack of autonomy. Managing exchange processes: Women are disadvantaged in daily buying and selling. |

Provide women with employment-based savings plans and educate them on cash management. Provide technology (e.g. calculators, mobile devices) and training (e.g. basic math courses) to help enhance numeracy and literacy. Give the women credentials that will enhance their social standing with abusive males. |

| Infrastructure Deficiencies | Physical safety: Transportation and public space deficiencies (e.g. illumination) put women at risk of physical violence, particularly those who work at night or have to travel long distances. Hygiene and sanitation: Lack of access to reliable sanitary facilities causes women to postpone their hygiene needs, which has severe health consequences. |

Invest in sustainable and safe infrastructure that provides women privacy (i.e. lighting, bathrooms, access to clean water, nursing/changing rooms). Implement a shuttle service that ensures women working late hours have a reliable and safe transportation. |

| Pressure to comply with gender/ethnic norms | Gender norms: Women are under pressure to balance economic and domestic responsibilities to preserve social standing and access. Engagement in the formal or informal economy is part of their caretaking responsibility, but often they are mocked for focusing on money making. Ethnic norms: Market traders face ethnically grounded demands such as contributing to community funds without regard to their financial situation and selling at a discount to family members and others related by ethnicity. |

Align workplace policies and conditions with local cultural and gender norms, such as providing time for prayer, allowing women to wear clothes that fit with their local culture, and allowing women to bring their children to work. |

| Inconsistent implementation of marketplace policies | Inequities: Market administrative practices guided by social class and ethnic biases contribute to invisibility and systemic exclusion of women operating in formal and informal economies. | Provide periodic training to merchant relationship managers to clearly communicate policy goals and mechanisms. Create open communication channels with law enforcement officers to ensure all voices are heard and avoid instances of policy-based exclusion. |

Lack of sleep, difficult work schedules, and incessant demands notwithstanding, many women market traders are ridiculed incessantly for not being “good mothers” and for “worrying too much about money.” Such remarks put considerable pressure on women to comply with irreconcilable gender ideals as they work in the marketplace, and many share that they feel “bad” because of the adverse social perceptions.

Additional complications may arise from women's role in managing family finances. In some societies, such as India and most Latin American countries, women have some latitude when managing family income and expenditures. In other societies, such as Bangladesh and Pakistan, only husbands or other dominant males (e.g. older brothers) manage money and make purchases. And even in societies where women have some latitude, dominant males generally rule the household and have final say on how family income is used. Moreover, violations of family income and spending norms are swiftly and brutally punished, suggesting that many women live with some level of fear day in and day out.

Gender factors are important when serving subsistence markets because retail sales – those important last-mile transactions that take place in open markets and door-to-door – are beneath the dignity and social standing of men in most subsistence societies and are hence what anthropologists call feminized labor. Women doing retail distribution work in subsistence markets share common concerns, such as husbands or brothers appropriating daily sales receipts for their own use (e.g. paying off gambling debts, partying with friends, other business ventures) and male customers refusing to pay for goods. Among women who operate in municipal markets, differential implementation of rules and regulations by the men who also work there also occurs.

Even when women market traders are successful and achieve relatively high levels of income, they remain vulnerable to the men both in their homes and workplaces. For instance, because of dominant males stealing their hard-earned cash, women market traders find innovative ways to safeguard their money, given that commercial banking is not a viable option for most of them. Some “roll the money” by reinvesting cash into gold jewelry and other nondepreciating assets that they can protect on their bodies, while others invest in savings circles and other forms of community savings plans to ensure their money is secure.

Also affecting women market traders are social norms that define how they should behave toward family or clan members. In some societies – in South India, for example – young married women must be deferential to mothers-in-law as much as to their husbands and, by association, to older women members of the husband's family. Many of the women traders talk about family members making fun of them on account of missing family functions and community ceremonies because of working in the marketplace and using those social norm violations as an excuse to demand money and special favors.

In some societies, such as Fiji, expectations may also involve deference to higher-status members of the clan or village. Demands from such people cannot be ignored, and may create significant problems for a woman market trader who is trying to maintain adequate inventory levels and pay for delivered inventory on a timely basis. High-status people, such as village elders and family matriarchs, asking for handouts mostly happens to Native Fijian traders. Not surprisingly, it is primarily those traders who highlight the social and communal aspect of their ethnic identities. Giving back to the society through soli events (charity), donations to the church, drinking kava,1 weaving mats with other women for free, and interest-free loans (seldom fully repaid) to family members and friends are common social practices that define Indigenous Fijian identity, irrespective of people's personal needs and level of income. Not surprisingly, saving money and aspiring to social and economic mobility and independence become a huge concern for many women market traders.

Women market traders find innovative workarounds for gender constraints. One example is embodied in Janaki, who has three children, a “not useful” husband, and sells milk door-to-door in Chennai, India (Viswanathan et al., 2010). She involves her children in milk deliveries while making sure they stay up-to-date in their studies; by utilizing her children, she violates her milk distributor's rules and local regulations. In addition, she has elaborate verbal arrangements with customers by which she sets daily prices based on clients' ability to pay on the spot and their past purchase loyalty. Janaki maintains a running balance of who received what concessions and when, which she uses to sustain equity among her customers while also being able to sell her daily milk quota. On a somewhat regular basis, she brings accounts up-to-date, demanding rectifying payments from customers who are in arrears and giving price breaks to customers who have in effect been subsidizing other customers by making full payments. Because Janaki's milk distributor frowns on price breaks and expects daily payments from her, she cleverly manages this complex retail system on her own, relying mostly on memory because she both is illiterate and cannot do even simple arithmetic. Her children help with the accounting, and she deals with a local loan shark when client payments fail to cover the daily payment that the milk distributor expects.

Gender factors create recurring constraints in the development and implementation of the small businesses that these women operate. Given the ways in which these factors are manifest, they should be the focus of ongoing monitoring and adaptation by companies. One example is the easing of credit and collection practices that has been implemented by companies such as Hindustan Unilever Limited in India. Initially, the company expected prompt payment from its (women) distributors and wanted them to adopt cash-only sales practices. Both constraints had to be eased in response to the behaviors of husbands and other family members, male clients, and corrupt law enforcement officers, which led the company to place adaption authority over company policies in the hands of merchant relationship managers – the people who personally provide inventory and collect payments from the market traders. Relationship managers are almost always local male merchants who are economically only one step above the women market traders and hence well versed in the nuances of the local market. Relationship managers understand how factors such as harvest cycles in rural areas or waves of police corruption after local elections in cities can broadly affect consumers' ability to pay; and more pointedly, they understand the frequency and intensity of demands for additional money from husbands and families of market traders. And these managers can allow women market traders the flexibility they need to deal with such unpredictable constraints. Giving relationship managers flexibility makes it possible to retain market traders, but it has also introduced operating rule breaking into the system and may affect profits adversely. Given that the likely outcomes from not allowing adaptation are a loss of market trader engagement and innovativeness and reduced market access to consumers in remote villages and urban slums, some companies working with market traders have chosen a rule-breaking approach. Similar flexibility in business practices seem advisable even when market traders are not women and constraints are not based on gender, but instead on other chronic constraints.

Social Class

Alongside the gender-based vulnerabilities affecting women market traders are social class inequities that lead to differences in access to resources and to unequal treatment. Practically all societies have some form of social hierarchy. In the United States, for example, people from low socioeconomic levels tend to have limited access to education, healthcare, and even retail shopping alternatives. Similar distinctions can be found in many European countries, and they may be related to ethnicity (e.g. the Romani) or religion (e.g. Muslims). In India, social class distinctions emerge from a centuries-old caste system that was affirmed by colonial powers until the 1940s. The caste system was constitutionally abolished in India, but caste distinctions remain embedded in the social norms that tacitly structure life within Indian within Indian communities worldwide. The caste system is interesting in that the correlation between caste level and wealth or income is not as high as in Western countries. High-class Indians can be poor, and low-caste Indians can be affluent.

Under socially enduring Indian caste distinctions, poor high-caste market traders (e.g. Brahmins) will likely have more access to resources and information than low-caste market traders (e.g. Shudras), and more latitude in their actions. If a Brahmin market trader complains to the market administrator, she may get more respect and responsiveness than if the complainer is from a lower caste. Similarly, higher-caste market traders will be listened to more attentively and respectfully when they speak on marketplace issues, and they may be given preferential access to government aid. In Fiji, social class differences exist between Native Fijians, who either own land or are members of a landowning clan, and Indo-Fijians (Fijians of Indian origin) whose ancestors came to the islands as indentured laborers and who are prevented by law from owning land.

Differences also exist between rural and urban dwellers. Indigenous Fijians from rural areas may actually enjoy higher social status than city-dwelling ones because their work upholds the Fijian cultural heritage. The same does not hold for Indo-Fijians. An interesting aspect of Fijian marketplaces is that caste-based distinctions that may have once been present among Indo-Fijians have virtually disappeared, likely because all Indo-Fijian share second-class status. Because Indo-Fijians cannot own land, they are overrepresented in the urban population, although some Indo-Fijians lease land for agriculture and live in rural areas. Because rural-dwelling Indo-Fijians almost never own their land, however, they are little more than indentured servants, and to the extent that urban dwellers have higher status than rural dwellers, Indo-Fijians who live in rural areas are at the bottom of the social class order.

In Fiji, Native and Indo-Fijian women market traders use ethnic differences to gain political power and cultural autonomy in the marketplace. For instance, the marketplace has formal or informal associations by which women market traders collectively voice concerns about working conditions and other issues (e.g. bathroom cleanliness). However, the voices of some women remain unheard primarily because of their ethnic identity. This insight came from an Indo-Fijian market trader who complained bitterly about the Native Fijian women switching conversations from English to Fijian whenever it was expedient to exclude the Indo-Fijians. Other Indo-Fijian women echoed the sentiment. In Fiji, English is understood by all ethnicities, albeit with different levels of proficiency. However, women belonging to one ethnicity may use their language in meetings to establish ethnic separation that enhances their political power and sense of superiority. This ethnically grounded separation tactic is possible in part because Native Fijians are overrepresented in market administrative positions.

In subsistence environments such as India and Fiji, social class distinctions are long standing, complex, and hard to change, and they can have a significant effect on how women market traders operate their businesses. In Fijian municipal markets, for example, Native Fijian and Indo-Fijian women market traders have side-by-side stalls and sell similar products, but market administrators respond differently to complaints based on the trader's social class status. Similarly, urban-dwelling market traders operate stalls inside the market building, while rural dwellers operate temporary stalls outside the building; market administrators enforce different rules for the two groups. Rural Native Fijians and Indo-Fijians who work the land are allotted special cultural capital in Fiji and are given permission to sell outside municipal markets buildings (not allowed otherwise) on Saturdays. They are expected, however, to observe market stall rules and pay market fees. Many market traders reported, however, that although technically against the rules, market administrators regularly allow rural traders to freely occupy open market stalls even inside the building and do not require them to pay marketplace fees. In effect, administrators are discriminating against urban market traders in violation of Fijian laws, and they defend the practices because of the importance of agriculture in Fiji's history and society.

As with gender-caused constraints, monitoring and responding to constraints caused by social class is important for companies, but for different reasons. Whereas gender-based constraints will likely apply equally to traders in a particular location, constraints based on social class create inequities within markets, and they can lead to radically different rule-breaking responses by traders. In Fijian markets, for example, Native Fijian women market traders seldom experience social class constraints, except for those created by market administrators implementing different rules for rural and urban traders. Constraints caused by social class, consequently, tend to elicit surprise, anger, and possibly open rebellion among the Native Fijian market traders. Rule breaking and innovation among Native Fijians is often very visible.

Indian Fijian women market traders, in contrast, are used to social class discrimination everywhere and hence respond to constraints caused by social class with covert workarounds and silent determination. Rule breaking and innovation among Indo-Fijian market traders is seldom overt or admitted to when exposed. Louisa (a Native Fijian trader) and Anita (Indo-Fijian woman market trader) exemplify these differences. Louisa openly (and loudly) highlighted how market traders have repeatedly complained at city council meetings about market administrators who allow violations of market stall regulations by some traders on account of their political connections or rural status. Anita, in contrast, was circumspect in her narrative and alluded in general terms to the Indo-Fijian women keeping a low profile and avoiding public conflict while working through coercive back channels to get more equitable administration of market rules.

Companies wanting to work in subsistence markets where social class constraints are present and wishing to identify the innovative behaviors that can be emulated elsewhere need to be assiduously observant of market trader behaviors. Moreover, they need to establish trust with market traders from different social classes in order to fully grasp how they are operating their businesses and innovating in response to constraints.

When Gender and Social Class Intersect

Additional complications from which we can learn arise when gender and social class intersect. When women market traders face constraints that differ from those facing males and women in lower social classes face constraints different from those in higher classes, the adaptations required are challenging. Gender and social class intersecting escalate the scope and speed of challenges, and adding other social identity dimensions, such as age, income, and education, to the mix places even more pressure on market traders.

When identity dimensions intersect, the constraints and pressures experienced by a person can be more than the sum of pressures coming from each constraint. Our research shows women market traders overcome the intersection of gender and social class constraints by embracing (and even encouraging) marketplace ambiguity and misdirection – which we define as a state of affairs where the changeability and inconsistency of social norms leave market traders with a sense of things being neither true nor false. Typically, Western firms view ambiguity and misdirection as detrimental to successful business practices. Among women market traders, however, they are a mixed blessing, because they create threatening conditions from which good things can arise.

Operationally, marketplace ambiguity and misdirection arise when norms are unclear, such as when administrators and other market traders forget the rules or misapply them, or perhaps falter in their applications because situations are unusual or novel. Market administrators are not more educated than the women traders (i.e. they have basic reading and arithmetic skills) and can be confused by new government regulations or by the entry of new market vendors. When marketplace ambiguity and misdirection are at play, women market traders often behave erratically, and they fluctuate between being highly energized or listless. Not surprisingly, marketplace ambiguity and misdirection is mentally and emotional taxing and likely contributes to the noted listlessness. Because marketplace ambiguity and misdirection can involve lapses in the application of discriminatory gender and social class constraints, however, they can alternatively create moments in which traders feel liberated, even if for short time periods; and that sense of liberation can be inspiring and energizing. A market trader experiencing momentary empowerment induced by an episode of ambiguity and misdirection might engage in highly innovative (and risky) experimenting with pricing, credit practices, and product delivery or presentation, experimentation that could alter her market reputation or reach.

An Indo-Fijian market trader named Krishna, for example, reported how she and others practice what amounts to dynamic pricing in order to manage the rate at which products sell throughout the day. The objective is to run out of stock at the same time that the market closes, instead of experiencing stock-out conditions or selling any remaining product at the end of the business day to vendors selling (illegally) outside the market after 5:00 p.m. Krishna experiments with her prices to accelerate or slow down demand for her products. Doing this requires constant monitoring of prices for the same product throughout the market, however, which is cognitively and emotionally draining because it triggers high levels of social disapproval (as she seeks pricing information from competitors) and is hence not something she can do every day. On days that ambiguity and misdirection leave her feeling energized, she engages aggressively in dynamic pricing. Other days she sadly accepts her business losses and the possibility that her children will go hungry that night. Krishna's story, similar to that of other market traders, makes clear that marketplace ambiguity and misdirection can trigger debilitating anxiety and marketing mistakes. Nevertheless, many women market traders take advantage of marketplace ambiguity and misdirection, in spite of its potential detrimental effects, because of the psychological comfort it can afford. They sometimes go as far as promoting ambiguity and misdirection by engaging in unexpected and disruptive behaviors, such as encouraging raucous complaining about bathrooms or engaging in loud arguing that forces market administrators out of their comfort zones.

When companies respond aggressively to innovation (rule breaking) that stems from marketplace ambiguity and misdirection, it can lead to mistakes, such as granting promotions to temporarily hyperproductive market traders who are otherwise mediocre in skills or terminating women market traders who are momentarily suffering but will be effective in the long run. Dealing with unpredictability in marketplaces is difficult, and having to manage women market traders who are made even more unpredictable by marketplace ambiguity and misdirection further complicates matters. Hence, it seems important for companies that rely on women market traders to accept the idea that traders may be more unpredictable, less emotionally stable, and more likely to break rules than retailers and individual salespeople might be. Concurrently they should expect greater and unexpected innovation, and they are hence encouraged to have processes that allow practice adaptation in different ways from how it may be implemented in other contexts.

10.3 Five Practical Suggestions

Table 10.2 offers five practical suggestions based on our examination of the innovative practices of women market traders, as we believe that understanding their approaches can be valuable to companies. Unique constraints, such as low literacy and numeracy, deprivation, unhygienic work conditions, and compromised legal and administrative systems, give rise to unique innovative thinking. It seems plausible, in fact, that the people best equipped to arrive at innovative solutions for subsistence markets are the women market traders who operate in those environments.

Table 10.2: Five practical suggestions for emerging market adaptation readiness.

| Practical suggestions | It will work because … | Look out for … |

| 1. Provide merchant relationship managers with graduated immersion experiences (e.g. single-week, multiweek, multimonth as needed). | Market rules and processes are sustained through stories. Immersion helps managers capture emotional and cultural nuances. Graduated immersion facilitates knowledge internalization. | Information or experiential overload. Relationship managers identifying too closely with specific market players or market factions (i.e. going native). |

| 2. Provide merchant relationship managers with training grounded in psychology and anthropology. | Mental models through which relationship managers can position and interpret market developments help maintain a balance operational consistency and situational sensitivity. | Relationship managers using mental model details prescriptively with merchants and other market actors. Models are frameworks and seldom are complete or fully accurate. |

| 3. Establish communities of practice for merchant relationship managers. | Idea sharing and peer conversation serve to encourage participants and broaden their grasp of constraints and opportunities in subsistence markets. | Overstructuring community of practice exchanges. |

| 4. Equip merchant relationship managers with information technologies (e.g. video capture equipment, cell- or satellite-based internet access) that facilitate quick problem resolution and information sharing. | Relationship managers will be better able to solve problems and provide answers locally while accessing global resources. In addition, such access will accelerate the logging of innovative ideas emerging from subsistence markets. | Equipment value becoming a crime endangerment factor for merchant relationship managers. |

| 5. Allow merchant relationship managers some latitude with individual merchant inventory levels and credit practices. | Relationship managers will have more flexibility to address individual-level and community-level cash flow constraints. | Reliance on hard-to-track cash transactions. Use mobile banking technologies whenever possible. |

As seen elsewhere in this book, adaptation readiness can be achieved through organizational development, design thinking, individual championing, and other approaches. In the case of subsistence markets, adaptation may be best carried out by the person or team who has direct managerial contact with the women market traders. We call those people merchant relationship managers. Their duties include recruiting women market traders, helping them manage cash flow and inventory, and coordinating across a disparate and unusual retailer group.

Because of subsistence market complexities, it seems wise that merchant relationship managers operate as autonomous distributors. When companies rely on distributors in developed economies, they leave most aspects of reselling (e.g. physical distribution, financing, returns, etc.) to distributors. In subsistence markets, merchant relationship managers will likely be employed by the firm and be responsible for administering company policies and processes. It is important, however, that they also be sufficiently trained and independent to deal with the localized and unique constraints that gender, social class, and marketplace ambiguity and misdirection can create. Next we expand on the five practical suggestions to achieve such ends.

Immersion Experiences

Firms should provide merchant relationship managers with graduated immersion experiences with the markets they serve, starting with weeklong introductions and building to multiweek or multimonth immersion as needed. Immersion duration depends on the trainee's background and familiarity with the target subsistence population. An example of extreme immersion is how Boo (2012) attained her award-winning grasp of life in the slums of Mumbai, India. Boo lived among the slum dwellers for a year, and she engaged in many of the same activities as her informants. Her goal was to grasp the physical and emotional effort required to deal with environmentally dangerous living conditions, corrupt law enforcement, and unemployment. Similar goals should be adopted by company immersion programs. It is important that individuals and teams dealing with women market traders be familiar with how the traders live and the demands they face. Boo achieved her insights by living with informants. Likewise, companies should promote to merchant relationship manager status people who have done market trader work, lived in their villages, walked in the slums, and traveled overnight from rural villages on buses and trucks. Shared nationality and cultural bonds are not enough, given that someone sufficiently educated to attain proficiency with corporate processes is not likely to have emerged from a subsistence environment where marketplace innovation is expected to arise. At least 30- to 90-day immersion experiences, however, are advisable.

Training Workshops on Related Consumer Behavior Concepts

At the same time, however, it is important for companies to protect their merchant relationship managers from identifying too closely with market traders. A second related suggestion, therefore, is for companies to provide relationship managers with structured training in consumer behavior and on how social and cultural factors shape human thinking and behaviors. Such training need not be formal classroom instruction but can instead be provided through self-administered instruction regimens of audio, digital, and print articles and books on topics like how the mind works, the role of emotions in decision making, and the importance of conversation and socialization to innovation. Training in the specific culture or cultures with which they will work is also advisable, and this involves not only the history and cultural profiles published in popular sources but also revisionist accounts that provide counterpoints to mainstream historical and cultural perspectives. In subsistence markets, likely many historical perspectives are shared across the generations and in the day-to-day verbal interactions of families and friends; relatively few if any historical accounts may be dominant. Many subsistence consumers and consumer merchants are illiterate, and even if they can read, they may not have had access to documented histories of their people and cultures. The goal is for merchant relationship managers to have detailed knowledge of how their clients think, feel, and behave – knowledge that help them understand what may be behind listlessness one day and euphoric experimentation the next – and know how to respond. Well-trained merchant relationship managers will be better able to consistently marshal and channel the women market traders' energies and innovative tendencies, to recognize when rule breaking may be allowed or must be curtailed, and to move between exerting control and giving latitude.

Communities of Practice

A third recommendation is to facilitate communities of practice for merchant relationship managers. Communities of practice are informal groups bound by shared expertise and passion for a joint enterprise. In most communities of practice, membership is voluntary, and whatever coordination arises is emergent and group driven. Communities of practice are deliberately unstructured and nonhierarchical, and they receive no formal charges from company management. Companies make them possible, however, because they help build member capabilities and shared knowledge. In companies serving subsistence markets, communities of practice would likely provide a setting where relationship managers can share insights and challenges pertinent to their market traders, help one another solve problems and identity innovation opportunities, and encourage one another. It is likely that community-of-practice participation by companies involved with subsistence markets will ebb and flow depending on local and global factors. It is also likely that participation will depend on information technologies and involve limited face-to-face interaction between members. Making such communities possible, however, can generate value. Companies can facilitate communities of practice by providing physical or virtual (see the next subsection) space where relationship managers can meet regularly. The space should provide some degree of confidentiality, sufficient for managers to share insights and discuss concerns openly. Further, companies can invest in low-cost computers, tablets, and possibly printing capabilities to help ensure adequate distribution of community-of-practice insights and recommendations throughout the organization.

Access to Information Technology

A fourth recommendation is to provide merchant relationship managers with information technologies such as video-capture equipment, and cell- or satellite-based internet access. As mentioned, one advantage from such technologies is to support virtual communities of practice when geographic and cultural distances make them necessary. An even more important benefit from such technologies comes from relationship managers having access to aggregated company knowledge while framing and solving problems at the local level.

Merchant relationship managers have to sustain trusting relationships with women market traders, and doing that requires sensitivity to local factors and norms. Relationship managers need to be both respected and appreciated, serve as both business sages and confidants, and have access to suggestions and solutions in the moment while not losing track of company objectives. Because women market traders are generally familiar with mobile information technologies, a relationship manager pulling out a smartphone to access distant databases will not likely seem scary or exclusionary to the women and hence may help maintain the all-important personal trust that relationship managers must treasure. One additional advantage is that it will greatly facilitate the sharing of innovative ideas (or unusual and thorny problems) that merchant relationship managers will likely encounter when working with women market traders.

Having systems that facilitate the logging and archiving of innovation successes and failures is a tried-and-true practice in companies that value creativity. To the extent that subsistence markets may be sources of unique thinking and solutions, companies should equip the most immersed and knowledgeable people to contribute promptly and easily to such archives. One word on caution with information technologies is to avoid brands and products that attract thieves and potentially place merchant relationship managers and market traders at risk.

Operational and Policy Autonomy

One final suggestion is to allow operational and policy autonomy to merchant relationship managers in subsistence markets. Even if companies expend the resources needed to produce subsistence market responsiveness as described, leaving reporting structures left unchanged will likely have these well-trained and equipped people working for supervisors and executives who would find it difficult to grasp the thinking behind relationship managers' decisions and points of view. With such a mismatch, it seems inevitable that at some point supervisor discomfort will rise to unmanageable levels and that the adaptation required to advance innovative solutions and best serve subsistence markets will be compromised or curtailed. As in other contexts, commitment to successful adaption in response to market idiosyncrasies should not be compromised by managerial ineptitude or inadequate organizational reporting structures. It may be good, in fact, to generally hold relationship managers accountable for business outcomes but not necessarily for compliance with documented business procedures. Such an approach admittedly opens the door to rule-breaking (deliberate or accidental) behaviors and possibly adverse outcomes. Given the seemingly intractable nature of constraints in subsistence marketplaces, however, they may be risks worth taking.

10.4 Conclusion

This chapter, based on explorations of women market traders in subsistence markets, provides unique insights into rule-breaking innovation under severe constraints and into some of the factors that contribute to such innovation. It also leads to practical recommendations for companies wanting to do business in subsistence markets and to rely on market traders to close the last-mile distribution gap endemic to subsistence economies. The insights arise from identifying discrimination factors pervasive in subsistence markets, such as gender and social class, and shown to disrupt the smooth functioning of business operations in subsistence societies. Market traders are further found to overcome such discrimination by engaging in clever rule-breaking behaviors and to embrace and sometimes encourage market ambiguities and inconsistencies that accidentally and temporarily allow them otherwise inaccessible opportunities. The chapter showed how intentional rule breaking is integral to day-to-day subsistence market practices and hence should be taken into account when designing, implementing, and managing business initiatives in subsistence contexts.

References

- Boo, K. (2012). Behind the beautiful forevers: Life, death, and hope in a Mumbai undercity. New York: Random House.

- Merton, R. K. (1957). Social theory and social structure. New York: Free Press.

- Prahalad, C. K. (2006). Fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: Eradicating poverty through profits. Philadelphia: Wharton School Publishing.

- Viswanathan, M., Rosa, J. A., and Ruth, J. A. (2010). Exchanges in marketing systems: The case of subsistence consumer-merchants in Chennai, India. Journal of Marketing 74 (3): 1–17.

About the Authors

DR. JOSÉ ANTONIO ROSA is Professor in Marketing and John and Deborah Ganoe Faculty Fellow at Iowa State University. He has studied topics such as the role of hope on innovation among poor consumers, boundaries between creativity and deviance among the poor, and how poor consumers use creative pursuits to cope with forced displacement due to natural disasters and violence. He has also investigated behaviors and decision making by low-literacy consumers, the social construction of product markets, and the role of embodied knowledge in consumer and managerial thinking. Dr. Rosa has taught marketing management, consumer behavior, and managing for innovation to undergraduate, professional graduate, and doctoral students and mentored doctoral students throughout his career. He holds degrees from University of Michigan, the Tuck School at Dartmouth College, and General Motors Institute (Kettering University). In his professional career, he held management positions in marketing and manufacturing in the automotive and banking industries.

DR. SHIKHA UPADHYAYA is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at California State University, Los Angeles College of Business and Economics. Her research focuses on the identity projects and multidimensional experiences of economically disadvantaged consumers in different consumption and marketplace settings. Her research provides important insights on consumption-related discrimination and disadvantage with implications in the areas of public policy and transformative consumer research. Dr. Upadhyaya teaches consumer behavior and social marketing courses and has held a range of marketing and business development roles at leading consumer and nonprofit organizations.