7

HOW TO DEVELOP LOW-END INNOVATION CAPABILITIES: ADAPTING CAPABILITIES TO OVERCOME CONSTRAINTS FOR CONSUMERS IN LOW-END MARKETS

Ronny Reinhardt

Friedrich-Schiller-University, Jena, Germany

Introduction

Low-end innovations are new products or services that expand a market by targeting consumers with a low willingness or ability to pay (WTP). Low-end innovations thus enable consumers who were previously unable or unwilling to buy due to high prices to buy the new product or the new service. For example, low-cost airlines such as Southwest or Ryanair expanded the air travel market for consumers who could not afford to fly. Similarly, GE's low-end medical devices enabled physicians in emerging economies to purchase medical technology to better diagnose and treat their patients.

Academics and practitioners use a range of related terms to describe innovations that address low-end customers. For example, the terms “resource-constrained innovation,” “frugal innovation,” “Base of the Pyramid innovation,” “inclusive innovation,” and “reverse innovation” are used by scholars and managers for low-end innovations in emerging markets. More general terms include “disruptive innovation,” “cost innovation,” and “low-end encroachment.” All of these terms are relevant because they address new products and services that expand the market at the low end. However, none of these frameworks comprehensively addresses the capabilities, methods, and tools that firms need to develop low-end innovations successfully.

7.1 Why Are Low-End Innovations Important, and How Do They Differ from Standard Practice?

Managers should care about low-end innovation – and thus low-end innovation capabilities – for two reasons. First, low-end innovations are an important means to seize growth opportunities, make profits, and develop strategic assets. Estimates indicate that the 4 billion people at the base of the economic pyramid spend about $5 trillion annually. Another 1.4 billion mid-market consumers spend roughly $12.5 trillion (Hammond et al., 2007). A 2015 Nielson study covering 30,000 respondents from 60 countries also suggests that affordability is the most important attribute for new product purchase decisions in both developed and emerging markets. In addition, innovative technologies priced below the going rate can have substantial disruptive effects, highlighting the strategic value of low-end innovation. For example, Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services such as Skype have essentially disrupted long-distance and international calling. Second, low-end innovations can make significant contributions to society, which is becoming increasingly important for stakeholders and consumers. For example, M-PESA, a mobile payment system developed in cooperation with Vodafone, has provided access for millions of Kenyans to the formal financial system.

However, low-end innovation faces specific constraints that require a capability set that differs from standard high-end innovation capabilities. Table 7.1 provides an overview of standard practices in eight different areas of innovation capabilities, constraints that low-end innovators face in these areas, and adaptations that help coping with these constraints. The chapter then briefly discusses the specific low-end innovation constraints and characteristics, providing an overview of the low-end capability dimensions and focusing on methods that can be used to adapt standard practice and develop a low-end innovation capability. Finally, the chapter outlines a process to help develop these capabilities.

Table 7.1: Innovation constraints and corresponding adaptions of standard NPD practice for low-end innovations.

| Area | Standard | Constraint | Adaptation |

| Innovation culture and commitment | Focusing on high-end innovation (“higher, faster, further”) Developing ambidexterity for incremental and radical innovation |

Low-end market appears inherently less attractive (e.g. low WTP, low-end technical solutions) | Foster low-end and suppressing high-end aspirations Create high-end/low-end ambidexterity and a switching culture |

| Cost reduction | Using process innovation to reduce costs in later NPD stages (e.g. after testing or launch) | Low WTP | Integrated cost-reducing innovation from the outset |

| Scaling | Scaling capabilities often beneficial but not always required (e.g. very high-end products, niche products) | High number of customers Low WTP |

High-volume scaling required from the beginning to reduce costs and serve low-end customers |

| Customer needs | Established and standardized methods for customer needs acquisition (e.g. Voice of the Customer) External providers of market research data |

Large distance (geographically and psychologically) between developers and customers (e.g. different abilities to pay) Heterogeneous needs |

Market immersion techniques to acquire distant customer needs |

| Innovation process | Using Stage-Gate–type processes Shortening NPD cycle times |

Heterogeneous and ambiguous needs | Highly iterative processes to reduce ambiguity Longer NPD cycle times may be required |

| Innovation scope | Focused innovation efforts on core problems | Market constraints such as institutional voids and lack of infrastructure or training | Total solution development to overcome additional market constraints |

| Distribution | Relying on existing distribution channels | Distribution channels nonexistent or a large number of consumers unable to access the innovation Low-end products viewed as unattractive by channel gatekeepers (e.g. target consumers with a low WTP) |

Develop distribution solutions that overcome access barriers Consider direct distribution |

| Networking | Collaborative efforts with upstream partners (e.g. universities) to solve technological problems | Infrastructural and institutional voids more important than technological problems Target customers' need for aid |

Networking with downstream stakeholders and gatekeepers that support target customers |

WTP – Willingness (and ability) to pay.

7.2 Which Constraints Do Low-End Innovators Face?

If a firm is fit for innovation, does that mean it is automatically fit for low-end innovation? Not necessarily. Low-end innovation introduces additional constraints limiting success that firms need to overcome.

The primary constraint for low-end innovations, as indicated, is a low WTP. New products or services need to be affordable – and not just affordable for the average consumer but priced low enough to create a significantly large market at the low end, including consumers who previously have not been able to purchase comparable products. This constraint is unique because it requires cost-reducing innovation and high-volume scaling from the outset, which may make the market and innovation appear unattractive for the organization and its partners. In addition, this constraint can also create a disconnect in needs and context understanding between developers, who typically have a high ability to pay, and low-end consumers with a low ability to pay.

In addition, low-end markets typically contain secondary constraints. First, market and consumer constraints such as underdeveloped infrastructures, institutional voids, and a lack of training pose challenges not typically present in high-end markets. Second, low-end markets consist of a high number of customers, which creates challenges with regard to scaling and distribution. In contrast to high-end innovations, low-end innovations cannot diffuse from the top of the pyramid. Instead, low-end innovators need to produce products in large numbers from the beginning. Third, in contrast to general perceptions, low-end consumers are heterogeneous, and low-end needs and contexts are not uniform but heterogeneous. A consumer in Kenya has different needs and faces different obstacles from a consumer in South Africa, in addition to the presence of different individual needs within a region. This creates ambiguity and fuzziness regarding needs and product requirements. These primary and secondary constraints require developing capabilities that firms pursuing high-end innovation may lack or adapting current capabilities to operate in new ways.

7.3 Adaptations: Methods and Processes to Develop Low-End Innovation Capabilities

The following sections explain the eight different operational dimensions that make up a firm's low-end innovation capability. I briefly describe each dimension and provide an overview of methods, tools, or processes that can support firms in building each dimension. Using these general methods can serve as a starting point to developing unique routines, processes, and tools that create a competitive advantage for generating low-end innovations for firms.

Develop a Low-End Innovation Culture and Commitment

The objective here is to create and maintain an organizational environment that supports low-end innovation. Contingencies to consider are that if you produce low-end products only, you must suppress high-end product bias. If you produce high- and low-end products simultaneously, you must develop a switching culture.

Successful low-end innovation requires management commitment to low-end innovation as well as a culture that supports developing products for low-end consumers because low-end innovation appears less attractive than high-end innovation. Thus, firms need to create and maintain an organizational environment that supports low-end innovation. Depending on whether the firm aims at developing low-end products only or developing both low-end and high-end products, different strategies are required. Low-end-only firms need a culture and commitment strategy that suppresses aspirations for high-end projects because “high end” is associated with superior products and status (but not necessarily higher profits). In contrast, firms pursuing low-end and high-end innovation simultaneously need processes that support switching between these two innovation targets.

If firms solely develop low-end products, they need to establish a low-end culture and suppress aspirations toward high-end innovation. These firms need an organizational identity that centers on cost and low-end customers. For example, Ryanair is well known for its extreme cost orientation and its focus on eliminating any frills to lower prices and enable more consumers to fly. Founder and chief executive Michael Leary constantly emphasizes the firm's goal to remain the price leader and thus suppresses any aspirations for moving toward the higher end. In contrast, Volkswagen (the “people's car”) did not suppress high-end ambitions when it introduced the Phaeton. However, the $100 000 flagship sedan never reached the sales targets, and the company reportedly lost $30 000 per car.

While an organization's culture may be the most difficult thing to change, three steps can support the process (DiDonato and Gill, 2015):

- The first prerequisite is awareness, which managers can raise using communication tools ranging from personal communication (e.g. meetings, team events) to printed and visual communication (e.g. posters, newsletters, mouse pads).

- After becoming aware of the desired low-end culture, the organization needs time to learn and adapt to the new culture. Learning requires in-depth understanding, which can be facilitated by workshops that cover different aspects of the intended low-end culture including successful examples such as Ryanair, GE, McDonald's, and Aravind Eye Hospitals.

- Employees and managers then need to practice the newly learned behaviors before they are made accountable for their actions. For example, in a practice period, research and development teams are assessed depending on the time they have worked on low-end and high-end projects. After the practice period, funds can be awarded and withdrawn depending on whether team managers have reached the low-end innovation goals. Establishing goals related to the low-end strategy is important because managers may end up in an activity trap, implicitly fostering high-end projects in the day-to-day business. Thus, management by objectives using SMART – specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound – goals supports low-end innovation culture and commitment and thus avoids having the low-end strategy become a toothless paper tiger.

Switching between conflicting goals such as developing high-end and low-end innovations is an even more difficult task for organizations. Innovation research has coined the term “organizational ambidexterity” to describe an organization's ability to pursue two conflicting goals simultaneously. In particular, there are two ways to achieve ambidexterity: structural ambidexterity and contextual ambidexterity.

- Structural ambidexterity means creating separate units each pursuing their specific goal. For example, the automaker Renault added Dacia as an independent brand to develop new models for the low-end market while Renault continued to serve the mid-range segment. This approach ensures that each unit can align the organization and the brand with the strategic goal. However, structural ambidexterity also impedes exploiting synergies because it may require parallel systems for research and development, production, marketing, and distribution.

- Contextual ambidexterity requires that all members of the organization divide their time and attention between low-end and high-end projects according to the firm's strategy. However, if managers do not distinguish between high-end and low-end projects explicitly, the firm is more likely to neglect low-end projects because decision makers implicitly associate high-end with status and success. Therefore, contextual ambidexterity requires discipline and adequate management tools to maintain a low-end/high-end balance. First, firms need an overall strategy that differentiates between low-end and high-end markets and sets individual goals for each target market. Second, firms can adapt existing portfolio methods to balance low-end and high-end projects. Most firms already manage innovation portfolios that balance radical and incremental projects; they can use the same approach for managing low-end and high-end projects. A portfolio approach that illustrates both low-end and high-end projects in the new product development (NPD) process helps to uncover early on if the firm cuts back on switching and loses its balance.

Thus, depending on the specific situation, firms need to suppress high-end aspirations or manage a switching process between high-end and low-end innovation; neither capability is standard NPD practice. Thus, a structured process that emphasizes awareness, learning, practice, and accountability can help to establish a low-end culture. Structural or contextual ambidexterity that differentiates between high-end and low-end projects enables a switching culture.

Integrate Cost-Reducing Innovation Early

The objective here is to innovate inputs and processes during NPD to reduce costs significantly. There are no contingences to consider, as this is a necessary capability across all contexts.

In contrast to traditional innovation projects, where firms most typically launch cost-reduction initiatives after the product has found initial acceptance in the market, low-end innovation requires cost-reducing innovation as an integral part of NPD because the target customers have a low WTP. Therefore, the capability to innovate the design, inputs, and processes in early stages of the NPD process to reduce costs significantly is essential for firms targeting low-end markets.

Low-end NPD teams can use cost-oriented tools such as Design-to-Cost, target costing, value engineering, and Design for Manufacture and Assembly to structure cost-reduction efforts from the outset. As a first step, independent of which of these tools are used, low-end innovators need to identify the product cost drivers. Typically, this analysis separates product inputs and manufacturing process steps into the few items that account for a large percentage of the final costs versus a large number of items that contribute to only a small fraction of the final costs (cf. ABC analysis). In a second step, these cost drivers are analyzed to identify cost-reduction opportunities.

Cost-reducing approaches from project outset include (Meeker and McWilliams, 2003):

- (Re)design for low cost. A large percentage of the final product's costs are determined in the design stage. Therefore, (re)design offers the largest potential for cost reductions. For example, both the Tata Nano and the Dacia Logan show that redesigning complex products like cars can lead to substantial cost reductions. In addition, Procter & Gamble redesigned the packaging of drugstore items and produced small sachets to make them affordable for low-income families in emerging markets, highlighting the cost-reduction potential of radical redesign even for relatively simple products. However, the multitude of starting points – ranging from changing the entire design or individual features, substituting input materials, to simplifying assembly steps – provides a challenge for low-cost innovators. Managers need to be aware that every design decision is a cost decision.

- Simplification. Low-end products cannot offer all the features that high-end products offer. Therefore, a critical step in the cost-reduction process is simplifying the product or the service until only the essential features for this particular low-end target market are included. For example, low-cost cars (Suzuki Alto, Dacia Logan, Tata Nano) eliminate features customers in traditional markets expect (e.g. power steering, cup holders) to achieve a lower price at a “good-enough” overall performance level (Wang and Kimble 2010).

- Component substitution and sourcing. Low-end innovators need to find new components that are cheaper and that better match the constraints in low-end markets. For example, GE designed a low-cost ultrasound device that uses commodity technologies such as notebook screens for imaging (Zeschky et al., 2011). Systematically screening for sourcing alternatives and the use of third-party solutions instead of internal procurement can reduce costs.

- Manufacturing and delivery. In addition to design and input factors, manufacturing and service delivery processes contribute to cost-reducing efforts. For example, low-end airlines have increased labor utilization; Walmart has developed sophisticated, low-cost logistics systems; and low-end cars are typically assembled in low-income countries. Thus, including manufacturing and process considerations into the NPD process as suggested by Design for Manufacture and Assembly and related methods is paramount for low-end innovation.

Finally, and in addition to these process-oriented methods, firms can also benefit from cross-functional NPD teams that include experts for cost reduction, sourcing, and manufacturing. This may be particularly important to truly integrate cost-reducing innovation into the early stages of NPD, which is not standard practice.

Scale for High Volumes

The objective here is to grow volumes rapidly to lower costs and serve a large number of customers. The contingency to consider is that for a small firm, this capability dimension is highly relevant. For a large firm, the capability dimension is less relevant.

Low-end innovation means developing affordable products for a large population of consumers who were previously excluded due to their low WTP. Thus, low-end innovation requires scaling processes that allow firms to increase volumes rapidly and flawlessly from the beginning. While scaling is important in many different contexts, it is essential in a low-end context to reduce costs and serve a high number of customers.

Therefore, developing high-volume scaling capabilities requires a design-for-many mind-set. During NPD, the development team needs to be aware that the final product or service must scale to the large volumes required to be successful in low-end markets. Thus, including high-volume manufacturers in the NPD process is important for firms that do not have high-volume production facilities. For example, American Biophysics developed the Mosquito Magnet, a device to capture mosquitoes using carbon dioxide. Although the product was highly successful after launch, the firm was ill equipped to manage the transition of the production process from the small-scale facility in the United States to a high-volume plant in China. Quality levels dropped and the product almost went off the market (Schneider and Hall, 2011).

In addition, high-volume scaling for low-end markets typically requires overcoming the paradox of realizing economies of scale by producing more of the same product while also adapting the innovation to the heterogeneous low-end contexts found across the world. Using a modular design approach can help overcome this paradox by providing both the required number of parts to achieve economies of scale and the required differentiation for different needs. Designing standardized modules and parts for these modules increases scale economy advantages but also allows for adaptations.

To do high-volume scaling, firms can rely on closed or open modular systems (Wang and Kimble, 2010). For example, the Volkswagen Group successfully uses the same modular platform (Modularer Querbaukasten, or MQB) for a wide variety of different cars, creating internal economies of scale (closed system). In a service context, scaling may require turning different variations of a process into one uniform process. For example, low-cost airlines only use a single plane type to achieve lower inventory levels for spare parts and uniform maintenance processes (Raynor, 2011). When the personal computer industry moved from a closed to an open system, external economies of scale enabled cost reductions, which facilitated the development of lower-priced computers that significantly expanded the market at the low end.

Thus, developing a design-for-many mind-set and systematically exploiting economies of scale using a modular approach can support firms in developing high-volume scaling capabilities, which are particularly important to overcome the constraints of low WTP and high number of consumers.

Acquire Knowledge about Needs for Geographically and Culturally Distant Consumers

The objective here is to understand low-end consumer needs by overcoming the geographical and psychological distance between the NPD team and low-end consumers. The contingency to consider is the distance between the NPD team and the low-end market. The further they are apart psychologically and geographically, the higher the relevance of this capability dimension.

Low-end customers are often geographically, culturally, or psychologically distant from the NPD team. For example, engineers in Germany and the United States developing new low-end products for the emerging markets are geographically distant from those markets. In addition, engineers from developed countries typically live in a different world compared to low-income consumers in emerging countries, which adds cultural and psychological distance between innovation designers and users. Thus, firms need capabilities to systematically acquire knowledge about distant customer needs.

Methods that help the NPD team immerse itself in the market's needs and experience the constraints can help bridge the distance. Market immersion, ethnography, and empathic design allow a deep understanding of distant customers. During market immersion, the entire NPD team – not just one employee from the marketing department – obtains firsthand experience with customers and the market. Similarly, ethnographic market research centers on observing consumers in their own environment. This method typically uses notes, videos, and interviews as data for analyzing and understanding consumer needs. In a similar vein, for empathic design, innovators find methods to put themselves in the shoes of the customers. For example, suits that simulate the effects of aging by constraining and slowing movement can help the NPD team to develop senior-friendly products. In a low-end context, market immersion means living in the low-end context, visiting the low-end context regularly, or trying to experience the low-end context using storytelling or videos. For example, in Procter & Gamble's “Living It” program, employees lived with low-income consumers for several days to experience their needs and constraints firsthand. As a result, the company developed the Downy Single Rinse fabric softener that allowed Mexican mothers, for whom good-smelling and soft clothes were important, to rinse once instead of several times and thus overcome the “newly discovered” constraint of a limited water supply.

Immersion programs are important to bridge the worlds of high-income employees and low-income consumers. Programs that follow immersion techniques, ethnographic methods, or empathic design provide a basis to develop capabilities for acquiring distant consumer needs.

Iterate Between Product Development and Market Feedback

The objective here is to gather and process information to identify and test solutions that overcome ambiguity and constraints. The contingency to consider is the level of ambiguity in the target market. The more ambiguity there is in the market, the higher the relevance of this capability dimension.

Iteration processes use a large number of short development and feedback cycles instead of a few but longer cycles. Iteration supports firms in finding solutions for the constraints in low-end markets and resolving ambiguity associated with low-end market needs. For example, GE Healthcare relies on Fastworks – an iterative process to develop, test, and commercialize affordable healthcare devices for emerging markets.

Two specific support methods incorporate the iteration principle: the probe-and-learn method and the lean start-up approach. Both methods follow a similar procedure that firms can use to structure their iteration initiatives and develop capabilities in this dimension. The first step, probing, introduces an early-stage prototype, a minimum viable product, or an immature product to the market. The product does not need to be fully functional or meet all needs of low-end consumers initially. In the second step, learning, the firm collects real-world feedback and data to learn about the market and the initial solution. In this stage, it is important to gather qualitative data firsthand. Survey methods that are reliable in traditional markets do not provide reliable results in a low-end innovation context because low-end innovation addresses a large number of consumers who have no experience in this product category. This makes a direct, quantitative approach less reliable than in-person observation. The third component, iteration, refers to repeating the first two steps until the product meets low-end market needs and overcomes existing constraints. Managers should avoid trying to achieve everything in a single iteration but instead cautiously evolve toward the final solution. The rationale behind this process is that learning through experience is much more useful in low-end markets, which tend to be quite ambiguous.

It is important to understand that iteration and improvisation are different. While improvisation is a flexible and spontaneous process, iteration is a structured, goal-oriented process. Iteration uses structured experimentation to eliminate uncertainty.

Develop a Total Solution, Not Just a Product

The objective here is to develop holistic solution systems adapted to low-end market conditions and barriers that enable low-end consumers to buy and use the innovation. The contingency to consider is the number of constraints low-end consumers face. The more constraints there are, the higher the relevance of this capability dimension.

Innovation in low-end markets requires coping with more constraints than innovation in high-end markets. Developing a total solution and the business model around these constraints can take longer to develop than low-end products themselves (Chesbrough et al., 2006). For example, low-end medical device firms need to develop device-servicing networks already available in traditional markets. They may need to develop training materials, find partners that are able to provide the service, and establish a financial model to pay for these services.

To start, total solution development requires in-depth knowledge about all of the constraints target market members face. Low-end market immersion and iteration processes can provide this information. Two additional methods can help the NPD team to find a solution. First, a knowledge management system that contains blueprints for solutions that have successfully overcome constraints can be used to transfer existing solutions to the specific context. For example, Honda introduced a lottery system to finance low-cost diesel generators in India. Each customer in a predefined group pays a fixed amount of money each month. Every month, one randomly drawn customer receives a generator, until all customers have received a one. This solution is likely applicable in a different context as well.

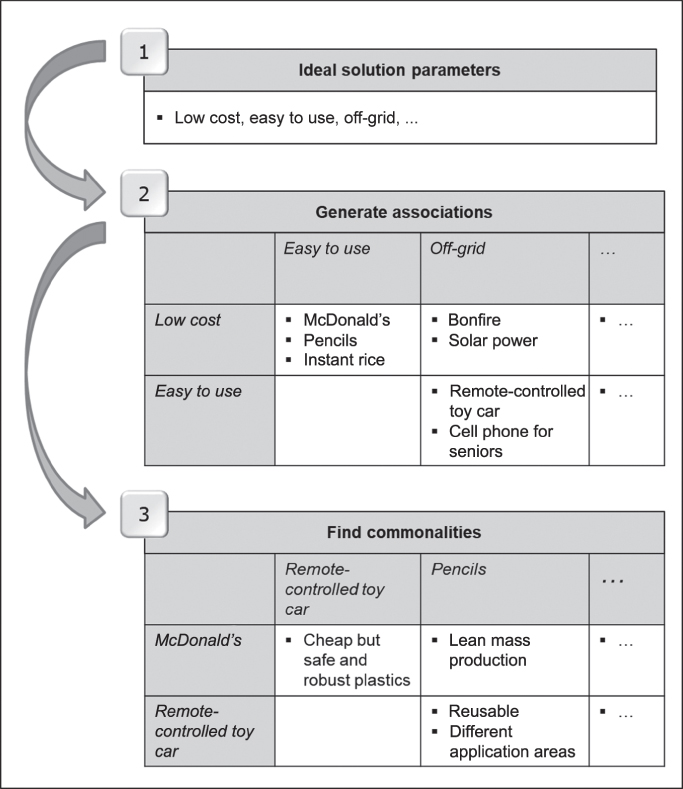

To develop entirely new solutions for existing constraints, this creative thinking technique can be helpful (see Figure 7.1 for an example). First, participants brainstorm five to 10 ideal solution parameters. For example, the product needs to be low cost, easy to use, and off-grid (i.e. not depending on public utilities). Second, these ideal parameters are combined to generate associations from each pair. For example, “low-cost” and “easy to use” can evoke diverse concepts like McDonald's, pencil, or instant rice. Combining “easy to use” and “off-grid” could evoke terms like “remote-controlled toy car” or “cellphone for seniors.” These associations are the first opportunity to generate ideas by transferring them to the actual low-end context. For example, the principle of McDonald's self-service can be translated to business-to-business markets. Dow Corning launched the Xiameter brand that automated the consumer transaction process as much as possible and used a direct approach to selling low-cost, standardized silicone products. If more ideas are needed, the initial associations can be used in pairs in the “commonality matrix” to find a commonality that is transferable to the low-end innovation context. For example, combining McDonald's with the remote-controlled toy car could evoke the commonality “cheap but safe and robust plastic,” which could serve as a starting point to develop new plastics-based inputs that previously relied on different materials. For example, the transport of solar panels used to rely on relatively expensive constructions made from wood. Robust, low-cost plastic edges lowered costs but also enabled a more efficient transport to reach geographically dispersed areas.

Figure 7.1: Creative thinking to solve low-end problems (example).

Thus, finding a total solution to cope with the constraints of low-end markets requires both systematic knowledge of existing solutions and creativity management to develop entirely new solutions that overcome those constraints.

Create Access for All

The objective here is to enable low-end consumers to access the innovation. The contingency to consider is the target market type. In emerging markets, firms need to focus on overcoming barriers; in developed markets, distribution access and diffusion are more important.

Creating access for low-end consumers to buy new products is important because low-end innovation can be successful only if it serves a high number of customers. In developed markets, the challenge often lies in accessing and selling the product into existing distribution systems and doing so in a cost-efficient way. In emerging markets, creating access refers to overcoming existing access barriers and institutional voids (e.g. lack of infrastructure or power supply). For example, Avon uses microfranchisees to reach people in the Amazon rain forest via canoes and boats, alleviating existing access barriers due to a lack of roads (Chesbrough et al. 2006).

In the face of barriers and institutional voids, three strategies can be used in isolation or combination (Khanna et al., 2005). First, the firm adapts its strategy to the low-end context and existing constraints. For example, while Dell was very successful using a build-to-order computer system in the United States and other developed markets, it used distributors and system integrators in China because internet usage was not as widespread and state-owned enterprises had unique requirements. Second, large multinationals may be able to change the context. For example, the Metro Group, a retail and wholesale company, established a cold-storage value chain that did not exist and therefore was able to sell fish and meats in urban areas in China. Third, if firms are unable to change or adapt to the low-end context, they may just have to stay away from the market. For example, Home Depot's business model relies on an efficient highway system to keep inventory costs low and enable low prices. Without certain systems and institutions like efficient highways, Home Depot may be unable to create a viable path for consumers in low-end emerging markets.

In developed markets, bringing the low-end product into existing distribution channels can be a challenge, because distributors may view low-end products as inferior and low margin. Changing the perspective toward total units and profits instead of profit per unit can help negotiate access. Alternatively, low-cost innovators can use direct distribution to ensure widespread diffusion at low cost. For example, DollarShaveClub.com and Ryanair were successful using a direct distribution approach. This approach, however, requires infrastructure, such as efficient postal systems and internet access as well as marketing capabilities to create consumer awareness. For example, DollarShaveClub.com was successful in creating viral marketing campaigns and Ryanair's chief executive, Michael Leary, continuously engages in publicity stunts, because creating brand awareness is an important success factor for direct distribution.

Thus, firms targeting emerging markets may face infrastructural and institutional voids. Adapting to or changing the context are two strategies that can help to create access. In a developed market, accessing existing distribution channels or establishing a direct channel are both viable but challenging alternatives to diffuse low-end innovations.

Network with Multiple Partners to Support Low-End Customers

The objective here is to connect with low-end consumers' stakeholders and gatekeepers to leverage existing distribution, protection, and support systems. The contingency to consider is the target market type. In emerging markets, firms need to connect with downstream stakeholders; in developed markets, engaging in strategic partnerships with gatekeepers is more important.

Strategic partnerships with stakeholders and gatekeepers help to access low-end markets. For example, Philips works with multiple partners to compensate for its lack of capabilities such as distribution knowledge for rural areas and marketing to the poor (Hens 2012). The Metro Group gained support from local governments for quality standards in exchange for bringing more food products into the tax net (Khanna et al. 2005). In general, research suggests that emerging-market low-end innovation projects benefit from government agency partnerships, because they often have social implications that are relevant to governments.

To structure stakeholder and gatekeeper integration for new product development, Vaquero Martín et al. (2016) provide a stakeholder model that is divided into three parts:

- Identification refers to the capability to find and access all stakeholders that influence market acceptance and success. Mapping stakeholder groups and understanding their stakes and power can facilitate a comprehensive identification process that avoids biased stakeholder selection. For example, managers may have easy access to some stakeholders in higher-end markets and may integrate this stakeholder group while other more distant stakeholders in low-end markets may be more important for success.

- Interaction refers to the capability to exchange information about the innovation with all relevant stakeholders. An open environment, using a common language, and adequate interactions methods such as face-to-face meetings all contribute to this capability.

- Integration refers to integrating the information from the stakeholders in the internal NPD process. Internal resistance against external input and difficulty in finding a solution to address stakeholder needs are challenges, while formalization using tools, indicators, and incentives can help in the integration process.

Thus, firms need a structured process to connect with relevant downstream stakeholders and gatekeepers that can support the low-end innovation project. These processes differ from standard practice focusing on upstream partners such as universities to solve technological challenges.

7.4 Defining the Path for Developing Low-End Innovation Capabilities

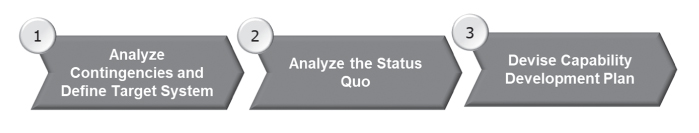

Low-end innovation requires many different capability sets; so where should firms start? First, the firm needs to analyze internal and external contingencies as described in each of the earlier sections and define the target system for their specific low-end innovation capability. For example, is the target market an emerging or a developed market? Does the firm innovate for low-end markets only or for both high- and low-end markets? The answers to these questions define the configuration of the target system. Second, managers need to analyze the status quo for each capability dimension. To what extent does the firm fulfill the required capabilities? For example, does the firm have high-volume scaling capabilities? Does it lack a low-end innovation culture? Third, the firm needs to devise capability development plans considering the possible ways to develop each low-end capability dimension discussed earlier (see Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2: Capability development process.

In Step 1 of the low-end innovation capability development process, firms need to analyze their specific situation with regard to internal (firm) and external (market) characteristics. Figure 7.3 provides the most important contingency questions, describes the situation of Example Inc., and provides the results for the target system of Example Inc.

Figure 7.3: Step 1 of the capability development process.

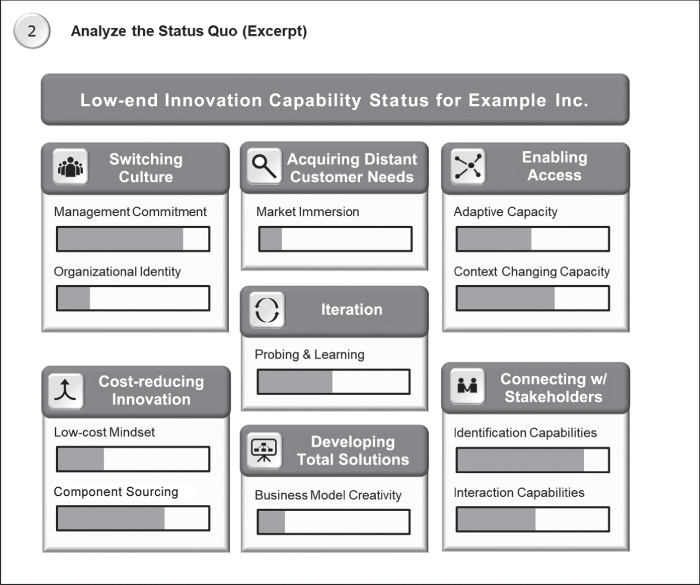

In Step 2 of the capability development process, firms need to analyze the status quo. Doing this requires determining several indicators for each capability dimension. Section 7.3 provides starting points for developing a coherent system of indicators. In addition, Step 2 requires finding a benchmark. For example, firms can use as benchmarks other firms that successfully serve the same or similarly constrained consumers, or they can define their aspiration level internally. Subsequently, the firm needs to assess the status as compared with the benchmark or aspiration level. Figure 7.4 provides an example of an aggregated result of Step 2.

Figure 7.4: Step 2 of the capability development process.

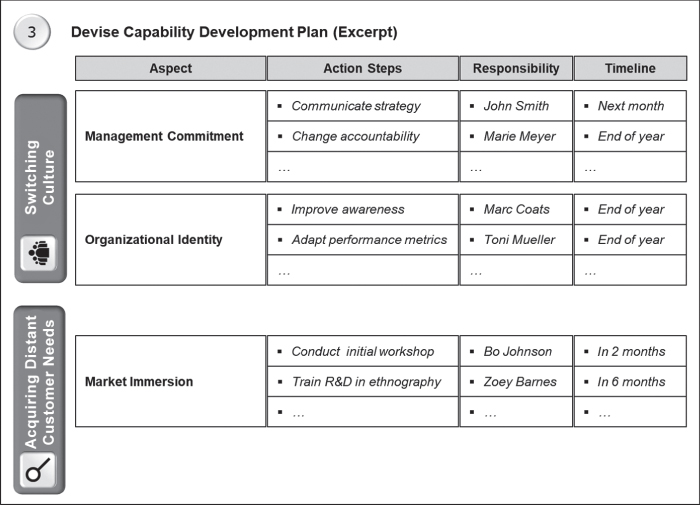

In Step 3, the firm needs to develop a specific action plan to improve inadequate capability dimensions. Section 7.3 of this chapter provides several examples for specific actions. The action plan needs to set objectives, define criteria for success, assign responsibilities and resources, and set target dates. Figure 7.5 provides an action plan excerpt for Example Inc.

Figure 7.5: Step 3 of the capability development process.

7.5 Conclusion

This chapter described low-end innovations and the constraints low-end innovators face. It also argued that low-end innovation requires a low-end innovation capability set that adapts standard NPD practice to cope with low-end constraints. This chapter explained adaptations in eight different low-end capability dimensions and provided ideas on how to develop a firm-level low-end innovation capability.

References

- Chesbrough, H., Ahern, S., Finn, M., and Guerraz, S. (2006). Business models for technology in the developing world: the role of non-governmental organizations. California Management Review 48 (3): 47–62.

- DiDonato, T. and N. Gill. 2015. Changing an organization's culture, without resistance or blame. Harvard Business Review 15 . https://hbr.org/2015/07/changing-an-organizations-culture-without-resistance-or-blame.

- Hammond, A. L., Kramer, W. J., Katz, R. S. et al. (2007). The next 4 billion: Market size and business strategy at the base of the pyramid. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

- Hens, L. (2012). Overcoming institutional distance: Expansion to base-of-the-pyramid markets. Journal of Business Research 65 (12): 1692–1699.

- Khanna, T., Palepu, K. G., and Sinha, J. (2005). Strategies that fit emerging markets. Harvard Business Review 83 (6): 4–19.

- Meeker, D. and McWilliams, F. J. 2003. Structured cost reduction: Value engineering by the numbers. Presented at The 18th Annual International Conference on DFMA. Newport, RI.

- Nielsen. (2015). Looking to achieve new product success? The Nielsen Company: Listen to your consumers http://www.nielsen.com/content/dam/nielsenglobal/de/docs/Nielsen%20Global%20New%20Product%20Innovation%20Report%20June%202015.pdf.

- Raynor, M. E. (2011). Disruptive innovation: The Southwest Airlines case revisited. Strategy & Leadership 39 (4): 31–34.

- Schneider, J. and Hall, J. (2011). Why most product launches fail. Harvard Business Review 89 (4): 21–23.

- Vaquero Martín, M., Reinhardt, R., and Gurtner, S. (2016). Stakeholder integration in new product development: a systematic analysis of drivers and firm capabilities. R&D Management 46 (S3): 1095–1112.

- Wang, H. and Kimble, C. (2010). Low-cost strategy through product architecture: Lessons from China. Journal of Business Strategy 31 (3): 12–20.

- Zeschky, M., Widenmayer, B., and Gassmann, O. (2011). Frugal innovation in emerging markets. Research-Technology Management 54 (4): 38–45.

About the Author

DR. RONNY REINHARDT is a Research Associate at the Chair of General Management and Marketing of the Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena, Germany. He received his PhD in Business Administration and Economics and his master's degree in Business Administration and Engineering from Technische Universität Dresden in Germany. His research focuses on innovation management with an emphasis on high-end and low-end innovation, decision making, and innovation adoption and resistance. Dr. Reinhardt has received numerous awards, such as the Academy of Management TIM Division Best Student Paper Award, the Innovation and Product Development Management Conference Thomas Hustad Best Paper Award, the Dr. Dietrich Fricke-Award, the Special Award of the Erich-Glowatzky-Foundation, and the Victor Klemperer-Certificate for his research and academic achievements. His research has been published in the Journal of Product Innovation Management, Long Range Planning, the Journal of Business Research, R&D Management, and Technological Forecasting and Social Change, among others.