2

A PRACTICE-ORIENTED APPROACH TO OVERCOME KNOWLEDGE-SHARING BOUNDARIES IN INNOVATION PROJECTS

Christiane Rau

University of Applied Sciences Upper Austria, Wels, Austria

Anne-Katrin Neyer

Martin-Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle/Saale, Germany

Katja Krämer-Helmer

University of Applied Sciences Upper Austria, Wels, Austria

Introduction

Informed by the open innovation paradigm and forced by increasingly complex products and services, it is presumed that more heterogeneous people are involved in innovation projects than ever before. This heterogeneity is a constraint that calls for special attention. While the heterogeneity of development teams can push creativity, it can also lead to inefficient collaboration. Unrecognized failures of knowledge sharing in early phases of the innovation process (e.g. about different understandings of customer requirements) can lead to severe problems, such as excessive costs for rework, when discovered only in market tests.

Intuition as well as extensive scientific evidence suggests that knowledge sharing in innovation projects is important and should be supported. While this argument is nowadays trivial to state, it is not trivial to achieve. Our experience in accompanying open innovation projects over the past six years indicates that companies regularly struggle to manage knowledge sharing among diverse, interdisciplinary coworkers.

Different mental models, previously acquired competencies, and resources can impede knowledge sharing among members of heterogeneous teams and foster counterproductive behaviors that can threaten the success of innovation projects. For individuals, innovations can put their acquired competencies at stake and make resources unnecessary. They may feel that knowledge sharing might threaten their own power and status in the organization.

With the increased cognitive distance among innovation team members and high levels of novelty of the shared knowledge, boundaries of understanding and boundaries of interests are likely to emerge among interdisciplinary, diverse coworkers. Those boundaries are manifestations of the individual constraints of heterogeneous team members. Our insights from various research projects, including an interview study with 24 innovation managers in Europe and a three-year case study at a large international organization in the sporting goods industry, show how boundaries of understanding and boundaries of interests emerge and how a modification of the standard innovation process by the means of specific innovation practices can help to dissolve these boundaries.

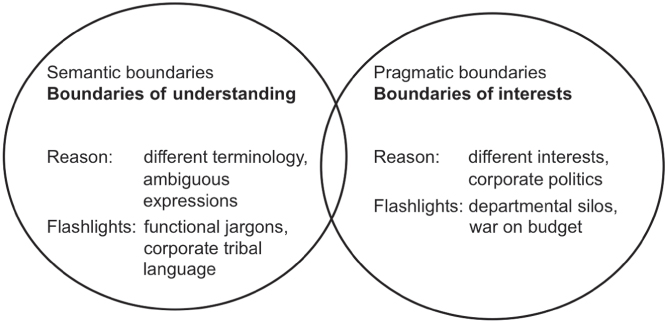

2.1 Knowledge-Sharing Boundaries in Innovation Projects

One of the challenges associated with understanding boundaries to knowledge sharing among heterogeneous coworkers in innovation projects concerns level of complexity inherent in communication. This complexity can be conceptualized along two levels. First, from a semantic level, information needs to receive meaning through the interpretation of each coworker. Research states that this is the first boundary level to appear. The second level, which is called the pragmatic level, puts the emphasis on how communication affects both the sender and the receiver. Our interest lies in these two distinct types of knowledge-sharing boundaries: semantic and pragmatic boundaries (see Figure 2.1). Semantic boundaries represent boundaries of understanding, whereas pragmatic boundaries represent boundaries of interests.

Figure 2.1: Knowledge-sharing boundaries in innovation projects.

Besides the general awareness of these two types of knowledge-sharing boundaries, it is essential to understand their relationship and interdependencies. Different types of boundaries can exist at the same time, making effective knowledge sharing even more challenging. We even found that individuals intentionally make up boundaries of understanding to mask existing boundaries of interests. For instance, we witnessed that developers pretend that misunderstandings exist to cover their unwillingness to collaborate with coworkers from other departments due to the existence of conflicting interests in the project. Together these two boundary types form the starting point to dive deeper into the black box of human behaviors when being confronted with innovation.

Boundaries of Understanding

Boundaries of understanding might emerge in innovation projects. Why is this the case? Each of us has a very particular perspective on how things should be done. This perspective derives from specific expertise and experience, which is developed while performing distinct tasks. What is happening is that knowledge is interpreted by referring to a specific context, such as a particular field of expertise. If knowledge is shared among peers (i.e. individuals from the same field of expertise), the interpretation of information is more likely to be similar. However, beyond this context, the same information might be perceived quite differently. In this situation, boundaries of understanding emerge that hinder knowledge sharing. In innovation projects such boundaries are a crucial cost factor. For instance, consider the terminology “minimum viable product.” We find extensive differences in the interpretation of this wording when comparing its use in the start-up versus corporate domain. Considering the increasing number of open innovation labs and corporate accelerators, it is crucial for corporate and start-up representatives to establish a common understanding of this terminology to ensure an effective collaboration.

Most boundaries of understanding remain unrecognized. If teams work together over longer time periods, they might participate in team building activities. As a side effect, a common understanding (in terms of terminology, jargon, etc.) among team members might but does not necessarily emerge. We rarely observed dedicated activities aimed at explicitly developing a shared understanding in practice.

So, why is it so hard for us to overcome boundaries of understanding? One answer can be found in our study with innovation managers in which we probed their experiences in running different innovation projects. What we learned is that there is not just “one” or “the” boundary of understanding but that three distinct types exist. First, coworkers might feel lost in the process of sharing knowledge. That means that they are not able to refer to tangible or familiar objects while engaging in knowledge sharing. Let's assume you have to describe an idea for a new service. You might have only a vague idea. Even if you have described the idea to the best of your knowledge, you might not be able to specify the target group, nor might you be able to explain the service delivery process in detail. This leaves a lot of room for (wrong) interpretations.

Second, team members might differ significantly in how they interpret what has been explained. We term this boundary resulting from fuzzy descriptions “fuzziness boundary.” Next, coworkers might use a terminology that their counterparts are unfamiliar with or that they interpret differently. This is the “terminology boundary.” Our minimum viable project example represents such a terminology boundary.

Third, coworkers have a particular mental model of their counterpart's work practices, corresponding timelines, and resources. If these assumptions are false, the so-called unbalanced mental model boundary hinders knowledge sharing. For instance, we found a product manager who tried to translate specifications for new software for information technology (IT) developers. He tried to explain the requirements in a way he thought the IT developers would understand. Unfortunately, he was not aware of the developers' programming process and complicated his explanation to a degree that the developers did not understand his purpose at all.

Boundaries of Interests

Boundaries of understanding and boundaries of interests have in common the need for the creation of a shared meaning among the coworkers. However, given the nuances of the boundary of understanding, we face the challenge to be very precise in identifying what type of boundary exists.

Boundaries of interests touch on another aspect: Individuals sometimes do not want to share their knowledge. Such intentional lack of sharing highlights the necessity to consider the divisional nature of organizations. Divisions (business groups, departments, functions, etc.) often clearly demarcate the knowledge property of a particular professional group. If new knowledge is created by one actor (e.g. in a particular department), and if this knowledge is then shared and integrated in an innovation project, then the value of the formerly leading knowledge holder in the respective domain might be perceived to be diminished. In short, one actor's knowledge affects the value of another actor's knowledge. This generates costs for the actor holding the previously unique knowledge. As Carlile states: “When interests are in conflict, the knowledge developed in one domain generates negative consequences in another” (2004, p. 559). No wonder that professionals aim at protecting their core knowledge domain from competitors. Dependencies in the face of novelty can create different interests among the actors, which might lead to knowledge-sharing resistance. As a result, so-called boundaries of interests emerge.

The findings of our study with European innovation managers further specify the concept of boundaries of interests. A “trajectory boundary” emerges when coworkers are required to gain new knowledge (or transform their existing knowledge), which generates costs and might lead to a loss of power. The term “trajectory boundary” refers to the intention of individuals to stay on the path (trajectory) chosen previously (e.g. a particular technological field of expertise), rejecting everything that would make them move outside their current trajectory of knowledge.

If coworkers whose primary task does not lie in engaging in innovation development are asked to share their knowledge for the sake of the innovation project, another type of boundary of interests emerges. We term this the “I-am-not-an-innovator boundary.” We found that team members' standard approach when they are confronted with boundaries of interests is either active resistance or passive avoidance of knowledge sharing. When subordinates recognize this harmful behavior, they eventually sanction it, but mostly the behavior simply remains unrecognized and threatens the project's success.

Regardless of what type of boundary of interests emerges, the challenge is to create shared interests and to stimulate the willingness to transform “currently” applied knowledge. Our research shows that the most powerful way to do so is the implementation of a consciously designed process dedicated to solving knowledge-sharing boundaries.

2.2 Solving Knowledge-Sharing Boundaries in Five Stages

We started the chapter by pointing out that our research explores the nature of different types of knowledge-sharing boundaries in innovation projects with a diverse set of internal and external employees. In particular, we are interested to better understand how these boundaries can be dissolved by the means of innovation practices. Innovation practices are all methods, tools, strategies, and concepts that are implemented to support the progress of innovation projects.

Here is the bottom line for innovation managers (executives and employees) alike: If you want your innovation projects to be a success, you have to dive deeper into those boundaries that hinder individuals in their attempts to engage in knowledge sharing. In the following text we present our four-stage self-assessment tool, which enables those who are involved in innovation projects to efficiently and effectively identify and resolve knowledge-sharing boundaries. The tool is based on an interview study with 24 innovation managers in Europe and a three-year case study at a large international organization in the sporting goods industry. The four stages of the proposed process are listed next.

| Stage 1: | Tracing hints. Learn to recognize relevant involved actor's behavior. |

| Stage 2: | Coming closer. Verify hints and analyze possible boundary types. |

| Stage 3: | Identifying “your” innovation practice.Choose an innovation practice based on your project's or company's specific context and needs. |

| Stage 4: | Getting to work. Implement the innovation practice and monitor effects. |

While going through the self-assessment tool, users might realize that others' input is needed for some questions. Thus, an important success factor of our tool is people's openness and willingness to engage with those who are involved in the innovation project, i.e. team members, coworkers, and managers. In this process, a discussion might be initiated that can lead to an insightful 360-degree exploration of the given situation. Beyond the insights provided by the results of the self-assessment, this dialogue itself might stimulate positive changes.

Stage 1: Tracing Hints

To grasp which boundary type exists in the project, it is important to know how to interpret the behavior of the involved individuals. To gain a feeling for this, you will have to collect and analyze the behavioral patterns of individuals working at the innovation project – in other words, you need to trace hints. Please bear in mind that some of those are more obvious than others.

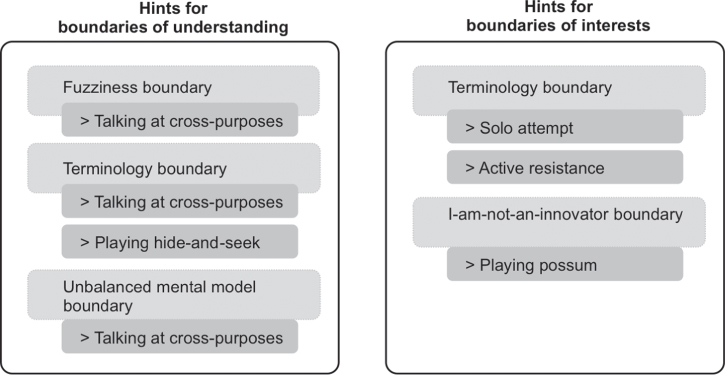

Let's have a closer look at the typical behaviors we found at boundaries of understanding. A first sign to recognize is whether individuals talk at cross-purposes (i.e. if two or more people talk about different subjects without realizing this and subsequently do not understand each other). Talking at cross-purposes occurs at each of the three boundaries of understanding (i.e. fuzziness boundary, terminology boundary, and unbalanced mental model boundary).

The importance of understanding hints in the context of a terminology boundary is also reflected in a behavior that we name “playing hide-and-seek.” In this case coworkers recognize that they lack understanding of specific terms but avoid asking for clarification, as they are embarrassed to do so. For instance, one innovation manager from a German automotive company stated that colleagues only have a certain time after they became part of the company to ask about abbreviations, which are regularly used in their research and development (R&D) team. Asking about fundamental abbreviations later makes a bad impression and can even threaten an individual's status within the group. Coworkers who face this or a similar situation keep silent or circumvent certain topics to avoid situations where their peers might notice their lack of knowledge. To understand this silence, we have to bear in mind that language is a way to preserve expert status and to build cohesion within a group. If a group has developed a shared language and individuals do not understand it, they might be rejected and might lose their status within the group.

If talking at cross-purposes and playing hide-and seek are signs that can be observed to identify boundaries of understanding, then the following question arises: What behavioral hints can be found in the context of boundaries of interests?

Earlier we introduced two types of boundaries of interests - the trajectory boundary and the I-am-not-an-innovator boundary. A trajectory boundary (requiring acquisition or transformation of knowledge) can often be observed at the interface between R&D and marketing departments. R&D employees push their new solution within the organization, trying to prove its value by succeeding with the approach. In contrast, marketing employees deliberately try to find ways to stop the organization pursuing the innovation by torpedoing the project. We named these behaviors “solo attempt” and “active resistance.”

In recent years, a trend to open up the closed process of product and service development to other people within and outside the organization has been observed. While this certainly provides new impulses for innovation, it can also lead to negative organizational consequences. Highly skilled and knowledgeable employees are often asked to contribute to innovation projects. The sheer number of requests can be overwhelming, especially if innovation managers or supervisors expect this contribution on top of employees' usual work without any compensation (or reduction of other tasks). In response, we found that people facing the I-am-not-an-innovator boundary do not react when being invited to join an innovation project; rather, they simply play possum. For instance, a service role-playing workshop was planned with the aim to act out and improve a new service at a large company in the sporting goods industry. The workshop had to be canceled twice, because all employees from a particular department did not respond to the invitation or canceled at short notice. The responsible innovation project manager speculated: “It's not related to the present core business, so it's at the very end of their task list.” Figure 2.2 summarizes which behaviors can provide hints regarding which knowledge-sharing boundary can occur in such heterogeneous team settings.

Figure 2.2: Hints for knowledge-sharing boundaries.

While looking for hints and reflecting on the behaviors and the corresponding boundaries in a specific innovation project, it will become obvious that some are more difficult to identify than others. Hidden behavioral patterns are the following: talking at cross-purposes, playing hide-and-seek, and playing possum. In contrast, the behavioral patterns active resistance and solo attempt are easier to identify and are referred to as “open” behavioral patterns. Regardless of the open or hidden nature of the behavioral pattern, you have to keep in mind that individuals at a boundary do not necessarily show these behavioral patterns. Therefore, an in-depth understanding of the dynamics is necessary. In addition, sensitivity is needed, as some behavioral patterns can be the result of multiple boundary types. Boundaries of understanding and boundaries of interests can exist in parallel. For example, the existence of conflicts of interests can even motivate coworkers to set up boundaries of understanding to sabotage the project.

The questions in Table 2.1 will support you in identifying hints from both hidden and open behavioral patterns in your innovation project.1

Table 2.1: Self-assessment reflection questions (Stage 1).

| Stage 1: Tracing hints | ||

| Yes | No | |

| 1. Could you observe that coworkers talk at cross-purposes? | □ | □ |

| 2. Do involved coworkers try to evade questions or circumvent certain topics? | □ | □ |

| 3. Do they circumvent topics related to specialized terminology? | □ | □ |

| 4. Do particular actors argue against pursuing the project? | □ | □ |

| 5. Do particular actors work to find evidence against pursuing the project? | □ | □ |

| 6. Do particular actors try to forge alliances with people who might want to stop the project? | □ | □ |

| 7. Is there an open conflict between two parties? | □ | □ |

| 8. Does one actor/party push a new approach (e.g. open innovation) while another heavily questions its usefulness? | □ | □ |

| 9. Can you observe that argumentation/confrontation between the coworkers is getting increasingly fierce? | □ | □ |

| 10. Do coworkers repeatedly fail to show up to meetings? | □ | □ |

| 11. Do coworkers not answer emails or telephone calls? | □ | □ |

The explanation of how to analyze the answers can be found in the appendix.

Stage 2: Coming Closer

By tracing hints and analyzing the involved individuals' behaviors, you have been able to get a first understanding of what type(s) of knowledge-sharing boundary exist in the innovation project. As a next step, we provide a set of questions in Table 2.2 that will help you to verify the knowledge sharing boundary type(s). Why is this important? Only when you know what type of knowledge-sharing boundary is influencing the success or failure of your project can you identify and implement needed innovation practices, which act as enablers for dissolving the boundary.

Table 2.2: Self-assessment reflection questions (Stage 2).

| Stage 2: Coming closer | ||

| Yes | No | |

| Boundaries of understanding | ||

| 1. Fuzziness boundary | ||

| 1.1 Did the boundary emerge early in an innovation project? | □ | □ |

| 1.2 Are the ideas and concepts still rough and fuzzy? | □ | □ |

| 1.3 Do the coworkers share ideas and concepts on intangible issues, e.g. services? | □ | □ |

| 1.4 Does the team work with representations to share knowledge?* | □ | □ |

| 2. Terminology boundary | ||

| 2.1 Do the coworkers use different terms? Can you observe that variations in their language exist? | □ | □ |

| 2.2 Can you observe that a domain-specific language is used by one of the parties at the given boundary? | □ | □ |

| 2.3 Did the parties work side by side and exchange knowledge regularly?* | □ | □ |

| 3. Unbalanced mental model boundary | ||

| 3.1 Are the coworkers aware of their counterparts' work processes and the settings they work in?* | □ | □ |

| 3.2 Did coworkers review each other's work processes, timelines and resources? Was there a kind of “reality check”?* | □ | □ |

| Boundaries of interests | ||

| 1. Trajectory boundary | ||

| 1.1 Does pursuing the innovation lead to additional effort for one of the actors, e.g. because the actor has to acquire new capabilities? | □ | □ |

| 1.2 Does the relevance of actors' existing knowledge decrease with pursuing the innovation? | □ | □ |

| 1.3 Might the actor face negative consequences (e.g. loss of power) if the innovation will be implemented? | □ | □ |

| 2. I-am-not-an-innovator boundary | ||

| 1.1 Is there evidence that actors perceive knowledge sharing enabling innovation projects as not being one of their legitimate tasks? | □ | □ |

| 1.2 Do the actors feel responsible for the project they should share knowledge for?* | □ | □ |

| 1.3 Is the actor asked to integrate his/her knowledge (not doing it on own initiative)? | □ | □ |

| 1.4 Do the actors face time pressures in doing their predefined core tasks? | □ | □ |

*Reverse question: Please count if you clicked “no.”

If you have clicked the box “yes” at a particular boundary twice or more (or “no” at a reverse question [*]), the existence of the respective boundary is likely. Now we need to identify a suitable innovation practice to overcome the given boundary.

Stage 3: Identifying “Your” Innovation Practice

Innovation practices are a suitable means to solve boundaries of understanding and boundaries of interests. Why is this the case? We conducted a systematic literature review of about 100 publications on innovation practices and have shown that they use a distinct set of boundary-crossing mechanisms to help teams to overcome their knowledge-sharing boundaries (Rau et al., 2012). But what are these mechanisms? To learn more about this, we observed the use of innovation practices in three innovation projects at a large international organization in the sporting goods industry over a period of three years.

Figure 2.3 presents an overview of which boundary-crossing mechanisms proved successful to overcome specific boundary types. Next we show why particular innovation practices are promising for distinct types of knowledge-sharing boundaries and what type of mechanisms they use. Furthermore, we provide exemplary innovation practices for each boundary-crossing mechanism.

Figure 2.3: Overview of boundary types, boundary-crossing mechanisms and exemplary innovation practices. Adapted from Rau (2012).

In the early phase of the innovation process, uncertainty and ambiguity are omnipresent. Are the ideas technically feasible? Which customer segments and which customer needs do they address? How will the implementation affect roles, work processes, organizational structures? Over time these ideas will mature and be transformed into concrete concepts, but at the beginning when they are rather vague, potential consequences are not likely to be clear to the project team. In this phase, the fuzziness boundary is often discovered among team members. We have witnessed the fuzziness boundary often in ideation workshops with introverted employees. The reluctance to communicate can increase the likelihood of the persistence of fuzziness boundaries. Whenever we encountered a fuzziness boundary, we used an interactive digital wall with a special application to combine collaborative work on a screen with individual paper-based work. The paper-based application enables participants to sketch their ideas on a special sheet of paper and to transfer it easily to a large interactive wall. On the wall, sketches can be compared and interactively refined. By working with these representations, team members can communicate their understanding and validate it with their counterparts. We found this mechanism of using representations to validate understandings and develop shared meanings regularly in innovation practices. We termed this boundary-crossing mechanism “developing a mutually understood language.” Other innovation practices based on the same mechanism include acting out scenarios or conducting user games.

In the innovation practice acting out scenarios, the matter of knowledge sharing is represented in a scenario, which the actors depict in a role-playing approach. In their play, the actors present their understanding of the situation, and the counterparts are able to relate to it. The actors are free to propose alternative interpretations and iteratively change the scenario.

Actors participating in user games create a web of interrelated stories about prospective users of a new technology. The game consists of sign cards, labeling the stories, and moment cards. An RFID-tag is attached to each moment card. When a person holds the cards next to an RFID reader, a 30-second video sequence is played. The videos consist of ethnographic field data. Actors lay out the stories one after another. After the first story, stories have to intersect and, thus, actors have to share cards. Gradually, a crosswordlike structure emerges. The game terminates when the actors agree that the new stories would no longer enhance the actors' image of the users (Brandt and Messeter, 2004).

If team members face a terminology boundary, for instance, the innovation practice “apprenticeship” can be implemented. At one large organization, a team member who was responsible for setting up a new lab overcame the terminology boundary between him and his colleagues from production by applying this innovation practice. He asked the production workers to teach him how to manufacture sports shoes. By learning their daily work processes, he also learned their specific vocabulary and was later able to utilize his colleagues' language. As a result, he was better able to communicate empathically and thus more efficiently in this heterogeneous team setting. We found innovation practices using the boundary-crossing mechanism learn and adapt the counterpart's language to be useful. Team members overcome the boundary as they observe their counterparts' behavior and learn about the particular context. More and more they gain the ability to understand and share their knowledge in their counterparts' language. Innovation practices using this boundary-crossing mechanism are, for instance, contextual inquiries or the completion of tasks with prototypes in the counterpart's context.

In contextual inquiries, team members conduct interviews in the environment of their knowledgeable counterparts to learn their language. Task completion with prototypes (in context) can also be applied to enhance knowledge sharing and overcome the boundary of understanding. Team members' understanding of their counterparts' perspective is enhanced as they observe the counterparts completing a task with a prototype. In addition, the counterparts are motivated to verbalize their thoughts.

If an unbalanced mental model boundary appears, we found innovation practices helpful in which an intermediary translates the knowledge between the team members either verbally or using visualizations. For instance, a graphical facilitator in a workshop or an ethnographer who visualizes customer insights using video collages can fulfill this role. Innovation practices of this category include the boundary-crossing mechanism engage a translator.

If a team faces a trajectory boundary, for instance, the innovation practice collaborative prototyping can be implemented. At a large company, we faced a persistent trajectory boundary between individuals of two groups in a project to design a new service for top athletes. While one newly formed group was in charge of designing the new service, the other group had previously been in charge of handling the services with the sponsored top athletes. Launching the new service would lead to significant changes in the work processes of the latter group and alter their role. In the workshop, employees of both groups applied collaborative prototyping to model the new service offering with LEGO Serious Play™. As they built the model together, both groups contributed alike. In the process, discussions emerged that were grounded in the LEGO representation at hand. In a negotiation process, the roles of the groups were clarified and a shared understanding of the service could be developed. When the service was implemented, the new group took the role of the technical experts, while the other group took on the role of masters of ceremony guiding the sponsored athletes through the process. We find that a team can solve trajectory boundaries most effectively if representations are available that can be changed cooperatively and iteratively to communicate and subsequently incorporate the boundary-crossing mechanism negotiate interests. On one hand, representations are strong stimuli to express interests; on the other hand, we observed that representations ground the discussion in a tangible object and thus focus the discussion on the issue itself. Thereby they reduce the negative influence of relationship conflicts and emotional reactions in discussions. Another innovation practice that can be used to support the negotiation of interests is the application of systems like Caretta.

Caretta is a system implemented to enable multiple actors to include their ideas in representations. Therefore, actors surround a shared space on which an object to be designed is visualized (e.g. for city planning tasks, a map of the respective city). Each actor is equipped with a personal digital assistant (PDA) that shows a representation of the object displayed in the shared space. Using the PDA, actors change the representation according to their ideas. Afterward, they initiate a data transfer from their PDA to the system controlling the shared space. The system runs a simulation visualizing the actors' changes overlaid onto the space. The visualization can be discussed and if consensus on the representation is reached, actors inform the system to replacing the former version (Sugimoto et al., 2004).

We observed the I-am-not-an-innovator boundary often when employees who are external to the core team and responsible for a new development are asked to contribute to the project. We found that it is necessary to first change the way actors perceive interests toward a perception that is more congruous with their counterparts' interests. We termed that boundary-crossing mechanism “reframe interests.” For instance, we observed an innovation project in which service staff members were reluctant to share their in-depth knowledge about customers. In the early phase, they saw the innovation project as not being part of their responsibility and presumably were afraid of imposed changes to their service process. Over the course of the project, the manager in charge was able to convey the understanding that the service staff members have an interest in engaging in the project, as this is where their future service will be designed. We did interviews with different members of the service staff and could see, over the course of the project, how their interests changed toward an understanding that they are now designing their own new service. This change subsequently led to more willingness to share knowledge. It is crucial to reframe the interests to make sure that people open up to a degree that they are willing to negotiate interests. We found that reframing interests can take place when assumptions are challenged or when team members internalize a shared vision. Otherwise, due to the playing possum behavioral pattern, team members are not available for any activities in which a negotiation would be possible. For instance, workshops are canceled on short notice. We suggest combining methods to reframe interests with those to negotiate interests.

Teams can apply the innovation practices ethnography or telling narrative vignettes to reframe interests. If team members do an ethnography in their counterparts' context, their assumptions about their counterparts might be challenged and their perspectives might change. Narrative vignettes can be told to share knowledge about relevant aspects of the offering, customer needs, etc. By telling narratives, team members can share how they make sense of the particular knowledge and create new visions about the future.

Given that a multitude of innovation practices are available for each boundary type, innovation practices must be chosen carefully. Often organizations prefer and apply certain practices highlighted by partners or at conferences without considering the appropriateness of those practices for their own specific situation. This often leads to a gap between the desired results and the delivered results. Organizations should focus on a set of factors to evaluate the appropriateness of an innovation practice rather than blindly applying it. Organizations need to identify and evaluate organizational as well as project-related conditions, such as resources, social factors, and the fit with existing organizational culture.

First, organizations need to consider the amount of resources required to apply a certain innovation practice. Organizations should first analyze whether they have the in-house competence to apply an innovation practice or if they need to collaborate with a suitable service provider. For the latter, organizations need to be aware of the growing service provider landscape. Thus, they should carefully screen different providers regarding their costs, expertise, and existing clients. Furthermore, organizations should also think about their own methodological expertise needed to apply the innovation practice. For instance, if the service provider supports an organization only during the method application, the organization still needs the in-house competence for the implementation of the results.

In an ideal case, organizations apply innovation practices to overcome existing knowledge-sharing boundaries for the longer term. Therefore, organizations also need to consider the “hidden” costs to guarantee the implementation of the results and the transfer in the organizational DNA. We know several examples where organizations dedicate a certain budget not only for the application of the innovation practice itself but for implementation of the results. For instance, not only do they include costs for the lead user workshops in their budgetary plans; they also commit a specific amount of the budget to transfer the results of such a workshop into concrete products or services. Innovation managers report that if the importance of the project is communicated to coworkers right from the project start, their willingness to be involved and to cooperate is higher.

Additionally, organizations should create a time schedule and milestone plan that covers the time and milestones before, during, and after the innovation practice application. If an innovation practice and the transfer of the results takes too long or crashes with existing timelines, an alternative innovation practice might be considered. If the innovation practice is going to be integrated for the longer term, organizations need to analyze whether this integration can target the core processes of the organization and, if so, what training is necessary to ensure an effective application. For instance, prototyping practices that are used to establish a shared understanding in heterogeneous teams could become a standard part of a company's innovation process at the fuzzy front end. If collaborative prototyping is then used in all heterogeneous teams, it is highly advisable to train the teams in the application of the specific methods, such as LEGO Serious Play.

However, the required resources are not the only issues that need to be considered. We recommend that organizations should further focus on their organizational culture and, in particular, the mind-set of the team members involved in the innovation practice. Will they accept and trust the designated innovation practice? Collaborative prototyping with LEGO Serious Play, for instance, is a very playful method. Organizations need to consider whether the organizational culture and the mind-set of involved employees is open-minded toward these playful approaches. Not every innovation practice is suitable for every organizational (innovation) culture. Ideally actors working in the innovation project are included in the choice of innovation practices. In that way, actors develop realistic expectations and their resistance during implementation can be decreased.

Stage 4: Getting to Work

Implementing an appropriate innovation practice is a crucial step in dissolving a knowledge boundary, but it isn't sufficient unto itself. Innovation project managers who want innovation practices to be a reliable, effective element of their boundary management practice need to make sure that these innovation practices deliver the expected results. Hence, the effects of implementation have to be monitored.

To determine whether the implemented innovation practices are successful in dissolving the identified knowledge-sharing boundaries and support knowledge sharing, innovation project managers might want to ask the self-reflection questions provided in stage 2 recurrently. In that way, they will be able to recognize if the boundaries were dissolved or if new boundaries emerged.

Ideally, experience gained by applying the innovation practices will guide the future choice of innovation practices. For instance, we proposed LEGO as a means to prototype a complex service process with a heterogeneous team that faced several challenges in their development journey over the course of about two years. At first, the responsible innovation manager was quite reluctant to try such a playful method, fearing negative gossip in the company. He agreed to utilize the method but instructed the facilitators to keep the workshop room closed and to close all shutters to the corridor. The workshop was a success. Team members stressed how this method helped them to interact constructively and to finally understand the other parties' contributions. Having experienced how the team appreciated this playful method led to more openness for future choices of innovation practices.

2.3 Conclusion

Companies struggle with the individual constraint of heterogeneity in their development teams. They frequently fail to manage knowledge sharing in innovation projects. Because such projects are increasingly complex, they are characterized by the work of a diverse, interdisciplinary group of individuals. In sharing one's knowledge with others, each individual is confronted with questions such as: Will I still be the expert if I share my knowledge? What will happen to my job if external innovators are seen as the upcoming experts? Do I really want to engage with people from different knowledge areas? How do I then have to adapt my knowledge so that others will understand it? Every innovation project manager will from time to time witness the emergence of knowledge-sharing boundaries in these settings. As mirrors of the individual constraints of team members, knowledge-sharing boundaries sometimes can be intuitively solved with moderation skills and sensitivity, but not always. Including innovation practices as a modification of the standard innovation process can provide meaningful support in dissolving these boundaries. Such innovation practices can alter destructive patterns of communication at a given boundary, refocus attention, or simply structure knowledge sharing in a way different from what employees at the boundary are used to.

In this chapter, we offer innovation project managers a five-stage self-assessment questionnaire that allows them to identify and resolve knowledge-sharing boundaries within project teams. The self-assessment questionnaire may be applied in a normative way because it helps users to decipher observed behavior and boundary types. It should be used as a basis for actively influencing the attitudes of individuals in innovation projects. It provides insights that help project teams to avoid systematic mistakes due to knowledge-sharing boundaries in innovation projects by pointing to nonideal tendencies and indicating corrective actions. This is particularly important against the background of increasing knowledge sharing among interdisciplinary individuals in today's innovation projects.

References

- 2bAHEAD (2016). Der Trend Index 2016.1. Available from: http://izz.sfu.ac.at/files/Executive%20Summary%20TrendIndex%202016.pdf

- Brandt, E. and Messeter, J. (2004). Facilitating collaboration through design games. In: PDC 04 Proceedings of the eighth conference on Participatory design: Artful integration: Interweaving media, materials and practices, ed. Andrew Clement and Peter van den Besslaar, pp. 121–131. New York: ACM.

- Carlile, P. R. (2004). Transferring, translating, and transforming: an integrative framework for managing knowledge across boundaries. Organization Science 15 (5): 555–568.

- Rau, C. (2012). Innovation practices: Dissolving knowledge boundaries in innovation projects. PhD.: University of Erlangen-Nuremberg.

- Rau, C., Neyer, A. -K., and Möslein, K. M. (2012). Innovation practices and their boundary-crossing mechanisms: a review and proposals for the future. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 24 (2): 181–217.

- Sugimoto, M., Hosoi, K. and Hiromichi, H. (2004). Caretta: A system for supporting face-to-face collaboration by integrating personal and shared spaces. In: Proceedings of the 2004 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2004, Vienna, Austria, 24–29 April 2004, ed. E. Dykstra-Erickson and M. Tscheligi, pp. 41–48. New York: ACM. https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=98592

Appendix

Stage 2: Analyzing Answers to the Self-Assessment Reflection Questions

A positive answer to a particular question provides a hint to the following behavioral pattern.

| Behavioral pattern | Questions (see Table 2.1) |

| Talking at cross-purposes | 1 |

| Playing hide-and-seek | 2, 3 |

| Playing hide-and-seek | 4 |

| Active resistance | 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

| Playing possum | 10, 11 |

The behavioral patterns you observed in your innovation project:

__________________________

__________________________

__________________________

__________________________

__________________________

About the Authors

DR. CHRISTIANE RAU is Professor of Innovation Management and Organizational Behavior at the University of Applied Sciences Upper Austria, School of Engineering. Currently, she serves as Head of Department of Innovation Management, Design, and Marketing. She is active in research, teaching, and consultancy in the fields of strategic innovation management, open innovation, and design thinking. Her research has been published in journals such as the Journal of Product Innovation Management, R&D Management, Creativity and Innovation Management, and Research Technology Management. She has a background in industrial engineering.

DR. ANNE-KATRIN NEYER is Professor of Human Resources Management and Business Governance at the Martin-Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg in Germany, where she directs the master's program in Human Resources Management. Her major research interests are in the field of human resource-oriented business governance for value creation. Currently, her research focuses on the impact of social interactions, organizational design, and human resource strategies on boundaryless cooperation and innovation in private and public organizations. Dr. Neyer holds a PhD from the Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration in Austria and received her postdoctoral lecture qualification from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Germany. She was a postdoctoral research fellow at the UK's Advanced Institute of Management Research at the London Business School.

DR. KATJA KRÄMER-HELMER is an expert on strategic innovation management and user-centered research in the fields of digital products and services. She is a dedicated innovation professional who gained practical insights working for companies such as HYVE Innovation Research, Sky Germany, and adidas, all in Germany. Her research interests are in the field of collaborative work environments, open innovation, and corresponding capabilities. Dr. Krämer is a lecturer at the University of Applied Sciences of Upper Austria and holds a PhD from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Germany.