6

BRIDGING COMMUNICATION GAPS IN VIRTUAL TEAMS

Donovan Hardenbrook

Littelfuse, Chicago, IL, USA

Teresa Jurgens-Kowal

Global NP Solutions, Houston, TX, USA

Introduction

New product development (NPD) projects are typically performed by colocated teams that easily communicate and share knowledge via informal means. Lean principles have evolved over time to reduce waste and, in the case of NPD, as shown in Table 6.1, to create reusable knowledge (Ward and Sobek, 2014). Lean NPD uses the best resources, regardless of geographical location, to optimize product development cycles while generating new, reusable, and transferrable knowledge. Yet capturing such tacit knowledge has typically been notoriously difficult for virtual teams,1 which can diminish the benefits brought to the organization by team members with richly diverse skills contributing to the team's work from various worldwide perspectives. Vital, day-to-day communications are in themselves more challenging when these virtual team members are scattered in different offices across geographical boundaries and various time zones.

Table 6.1: A comparison of standard and lean NPD.

| Organizational structure | Standard NPD | Lean NPD |

| Environment | Stable conditions | Uncertain environment |

| Long cycle time | Reduced cycle time | |

| Practices | Stepwise product improvements | Customer-centric continuous improvements |

| Multiple iterations | Process waste reductions | |

| Teams and Leadership | Colocated teams | Virtual teams |

| Specialized skill sets (“I-shaped” people) | Generalized/specialized skill sets (“T-shaped” people) | |

| Limited working hours | Anytime, anywhere connectivity | |

| Outcomes | High development cost | Cost efficient product development |

| Project-specific data | Reusable, shareable knowledge |

Companies can reduce long cycle times and high development costs by taking advantage of global assets, such as reusable and repeatable knowledge of customers, markets, and technologies. Utilizing the concepts of lean NPD to improve virtual team communications can lead to increased innovation throughput and quality. In this chapter, we focus on bridging the inherent communication gaps that can plague virtual teams and reduce their overall innovation effectiveness. We describe a virtual team model (VTM) with five key elements2 that allow a dispersed team to benefit from lean principles in creating reusable knowledge and, with implementation, make the virtual team even more competitive than traditional, colocated product development teams. Crucial to effective NPD is the capture and dissemination of innovation knowledge that is both process and product specific. Communication drives the creation of reusable, shareable knowledge.

6.1 A Lean Team Is Virtual in NPD

Traditional innovation utilizes a waterfall process implemented by a colocated, cross-functional team. In fact, the colocation of teams working on breakthrough innovations is often encouraged, suggesting that such a structure can lead to higher productivity. Yet colocation of team members may not be feasible or desirable due to cost factors and other organizational constraints. For example, product development assignments in a matrix structure represent only a fraction of a team member's workload. Furthermore, staff may be restricted geographically due to work, family, or health concerns. Thus, NPD efforts are often forced to utilize team members in different locations. Communication is primarily via digital media with little, if any, face-to-face (F2F) contact among team members. This is what we call a virtual team.

In the realm of NPD, virtual teams reflect a direct implementation of lean principles. The core concept of lean manufacturing is to reduce waste and improve quality. Lean NPD reduces waste by improving knowledge sharing among and between team members to speed up cycle time as nascent ideas are converted to commercial realities. Several aspects of teamwork either help or hinder the ability of an NPD team to accomplish these goals, including how the team is formed, how it communicates, what operating protocols it follows, how knowledge is captured and shared, and which leadership styles guide and frame the team's progress toward its objectives. A virtual team embodies the lean principles, as shown in Table 6.1. Applying the VTM framework allows organizations to overcome assumed barriers introduced by dispersion and to capture the benefits of lean NPD.

6.2 The Basics of Virtual Teams

Half of all virtual teams fail to meet their goals (Connaughton and Shuffler, 2007). Failures are attributed to differences in time and space, cultural differences, poor working relationships, lack of coordination and communication, lack of trust, low accountability, ineffective organizational structures, and reliance on individual contributions. The quality of work produced by a virtual team declines as the degree of dispersion increases (Monalisa et al., 2008). Dispersion is measured by the number of miles or time zones between team members, number of locations per team, percentage of isolated team members, and unevenness of team members (Siebdrat et al. 2009). Unevenness is demonstrated, for example, by having five team members at one site and only one or two team members at other sites.

Various sources define virtual teams differently. It is perhaps illustrative to define a colocated team that is traditionally used for NPD work and contrast it with the virtual team. Members of conventional colocated NPD teams work near one another – geographically, temporally, and culturally. These teams use informal communication methods and build social relationships through close interactions among team members. Social sharing further builds trust, which leads to greater collaboration and creativity. These traits are desirable for efficient innovation by a team of cross-functional professionals.

Virtual teams, in contrast, are more cost-effective than traditional teams, and a virtual team can advantageously tap into local markets for knowledge sharing across the team, the product line, and the global organization. Virtual teams can be described as “work arrangements in which a group of people share responsibility for goals that must be accomplished in the total, or near total, absence of face-to-face contact” (Zofi, 2012, p. 1). Unfortunately, many organizations have soured on virtual teams because of poor practices, inadequate communication among team members, and failure to deliver promised outcomes. Resorting to traditional colocated development teams, however, can drive up the cost of design and development, slow time to market, and limit creativity.

The Challenges of a Virtual Teamas an Organizational Constraint

Note that dispersion of team members becomes a communication constraint whenever electronic communication replaces F2F conversations. For instance, team members located on different floors of the same building encounter some degree of physical dispersion resulting in communication and coordination challenges nearly as great as teams located in different countries (Siebdrat et al., 2009). As physical distance increases, team affiliation declines due to a lack of social or F2F interactions.

Because of dispersion, most communication within a virtual team is technologically mediated, meaning that the team's work is supported primarily by various information technologies. Unlike a traditional team that develops normalized practices by sharing a common work space, virtual teams are separated by time, space, organizational function, and culture. Pure F2F NPD rarely exists in today's globally competitive environment, where time to market for new products is critical and in which developers must consider a worldview in designing new products or services.

A Model for Effective Virtual Teams

As gleaned from our own experiences and those of other virtual teams, we have framed a model for virtual teams that drives knowledge sharing and active communication to support efficient product and process development. The model presented in this chapter is built from the authors' firsthand experiences, observations, research, and implementation of work practices. The model was refined based on application to different real-life virtual teams as well as literature and management case studies, as indicated in the “Driving Virtual Team Improvements” box.

Specifically, the key elements in the VTM are:

- Initiation and Structure

- Communication Practices

- Meetings and Protocols

- Knowledge Management

- Leadership

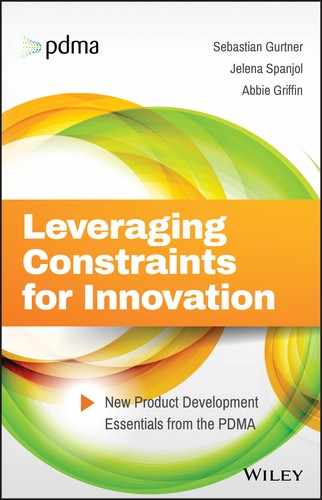

Each element of the VTM is accompanied by several supporting practices that have been revised and refined over the years as application of the VTM evolved and improved. An NPD team can immediately realize enhanced communication pathways by implementing any of the elements or practices in whole or part. However, the VTM is most successful for NPD teams that establish the practices within each element and apply the model universally since the elements and practices intertwine with one another in the complex relationships necessary for successful NPD (see Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1: A lean NPD virtual team model (VTM).

The first element, Initiation and Structure, addresses team member characteristics, team formation, and goal-setting. The next elements, Communication Practices and Meetings and Protocols, define practices that help virtual teams overcome the natural barriers faced by people working outside of informal, F2F relationships. Of course, to meet the objective of a lean NPD team, virtual teams must find efficient and effective ways to share knowledge. Systems and best practices for Knowledge Management are presented in the next element of the VTM. Finally, no team can be successful without effective Leadership, and this last element of the VTM includes three practices that support unique skills to lead a virtual team. In this chapter, we highlight a subset of the practices to implement for successful innovation projects. An example application of the VTM is provided in the appendix to this chapter.

6.3 Initiation and Structure

Initiating a team and designing the proper organizational structure is even more important in a virtual team than in a traditional, colocated team. Leaders must select team members based on interpersonal skills in addition to technical expertise. Effective virtual teams start with hiring for purpose in which team members are vitally connected to the mission and overall goals of the NPD effort.

Because team members are often isolated from other designers and developers, hiring for purpose requires a more extensive skill set match as well as identification of personal characteristics, such as individual leadership, that will enhance virtual team communications over the product development life cycle. Firms can screen for both staff and project positions based on connections to their mission before interviewing candidates, thereby prepopulating the potential pool of virtual team members with devoted and enthusiastic people. An organic food and beverage company, for example, may hire for purpose by screening applicants for their commitment to family nutrition and the environment. A fitness center may screen applicants for their commitment to a healthy lifestyle and service to others. A private school may screen applicants based on their dedication to values and knowledge transfer. Virtual teams require participants who are strongly committed to the values and mission of the firm to represent the company and the project effort.

Individual Leadership

Conventional colocated NPD project team members are usually selected for project work based on functional ability and availability. While these are important characteristics of virtual team members as well, the successful initiation and structuring of a virtual team depends on the personal motivation and leadership of individual team members. Self-motivation serves not only to drive passion for the NPD project goals but also supports other elements and practices within the VTM, such as communication and individual leadership.

However, individual leadership goes beyond self-motivation and self-direction. Virtual team members with individual leadership carry out project tasks independently and value cross-functional relationships with other team members. While conventional team members participate in project teams as specialists, virtual team members cross the boundaries and fill roles of “generalist/specialist” as shown in Table 6.1 to support lean principles of knowledge transfer. Isolated team members direct their own work and do not necessarily need a strong central leader. (The role of the virtual team leader is discussed later in this chapter.) Individuals are frequently assigned project activities that leverage their strongest skill sets, such as planning, designing, or analyzing. Virtual team members demonstrating individual leadership work to complete their own tasks within their specialization but can support the team as a generalist as necessary (“T-shaped” people). For example, a team member in Japan may be a specialist in fluid flow but can represent the local customer's need to the rest of the NPD team in a general way. As such, the generalist-specialist capability deployment helps to reuse knowledge and communication to drive the project goals.

Individual leadership on a virtual team is contrasted with task-oriented membership in a traditional team. Colocated NPD team members tend to act as subject matter experts working piecemeal on a project. Traditional teamwork includes bounded hand-offs between functions while team members represent a single skill set (“I-shaped” people). Project inquiries are referred to the project manager who represents the overall team. Virtual team members serve multiple functional roles and represent the whole project within their geographical region or market sector. This requires both breadth and depth of product knowledge rather than solely functional expertise.

Of course, a team leader will consider individual leadership during team formation, and individual leadership is interwoven throughout the other elements of the VTM. In particular, we see how individual leadership helps to build broad communication pathways and creates efficient Knowledge Management systems. Further, individual leadership establishes the foundation for knowledge transfer when the virtual team disbands and transitions to new roles on other projects.

Shared Goals Initiate Virtual Team Communications

Choosing the correct team members with appropriate characteristics is crucially important for the success of a virtual team. Virtual teams must be even more proactive, deliberate, and disciplined in their interactions than traditional colocated teams. Therefore, team formation must include team member selection to represent all areas of technical expertise required to complete the project as well as evaluation of personalities and abilities for individual contributors, such as self-discipline, motivation, and leadership. Forming the team is an exercise that brings together the diverse team members from around the world to join in a common cause. The mission of the NPD team is reviewed and revised through the practice of team formation in the VTM.

Technology

Technologically mediated communication is less rich than F2F interactions. It can lead to a source of confusion and misunderstanding that negatively impacts the virtual team. However, the use of technology allows an organization to realize the benefits of distributed workers to identify local customer needs and bring a global perspective to the product development project. We suggest a few team collaboration tools later in this chapter.

Any technologies that will be used for team collaboration, communication, or knowledge management should be introduced at the project kick-off meeting. Adequate training on new tools and expected usage of these technologies should also be provided at the kick-off meeting. To increase productivity of team members, this same tool set should be utilized continually throughout the project. New or improved software should not be introduced during the project unless all team members have received training and have agreed on communication protocols to utilize the new technology.

Communication standards and meeting protocols are critical for success of a virtual team and are established up front for a virtual team. Team operating rules set expectations for communication and team member interactions. Again, these communication standards overlap with the second and third elements of the VTM; however, establishing general and specific expectations during the team formation process will reduce conflict during team formation and ensure later successes in team performance. For example, setting initial team protocols regarding meeting format and attendance allows every team member, regardless of his or her location, to be prepared for and responsive to group norms.

As indicated, the best members for a virtual team are self-starters who are motivated by the task and have high degrees of emotional intelligence and cultural awareness. Individual leaders will maintain a focus on customers and stakeholders throughout the project. Moreover, shared goals drive commitment to the work and is the number one measure of success for a virtual team. Establishing shared goals is a key practice in initiating and structuring a virtual team. Commitment to shared goals results in successful team performance. Shared goals should be disseminated at the kick-off meeting and reinforced frequently by the leader in order to balance work distribution and enhance team member cohesion.

According to Hoegl and Proserpio (2004), successful virtual teams focus on the shared goal by

- Open sharing of information,

- Task coordination,

- Balanced distribution of work,

- Mutual support with cohesion, and

- Task effort.

It may take more energy and time for a virtual team to initially agree on the mission and goals of the work. Yet the problem definition should occur synchronously for the virtual team to enhance commitment to the project. The team must also share a common understanding of stakeholder expectations. Maintaining a relentless focus on the customer leads to higher success rates for virtual teams and drives the lean principle of customer-centric, continuous improvement.

Initiation and Structure: Action Steps

In order to successfully meet product development and knowledge transfer objectives using a virtual team, an organization must be deliberate in initiating and structuring the team. The VTM includes several practices demonstrated to establish team characteristics and behaviors for successful NPD project execution. The first element, Initiation and Structure, is perhaps the most important element of the VTM because errors and omissions in setting up the team are not easily overcome later. Table 6.2 illustrates the scenario of a new team leader setting up a lean, virtual team for product development work, focusing on the Initiation and Structure of the team. As the elements of the VTM naturally overlap, you will begin to recognize the value of the other elements – Communication Practices, Meetings and Protocols, Knowledge Management, and Leadership – and their influence on the Initiation and Structure of the virtual team up front, as discussed later in this chapter.

Table 6.2: Establishing a new virtual team for product development.

| Scenario: You have been assigned to work as part of a virtual product development team. You are serving as the team leader and there are two other team members colocated at your site in Canada. There are three team members in different cities in the United States, one team member in Asia, and another in Italy. | ||

| Virtual team model | Standard approach | Actions for lean NPD |

| Initiation and Structure | Select team members based on skills and availability. | Select team members with individual leadership characteristics who are committed to the project goals. |

| Communication Practices | Face-to-face. Informal. |

Establish communication norms being aware of time zone differences. |

| Meetings and Protocols | Frequent status updates. Informal water cooler conversations. |

Set up predictable, routine meetings but be respectful of different time zones. |

| Knowledge Management | Tacit knowledge is transferred in a project of long-standing team members with specialized skills. | Establish and enforce Knowledge Management norms. Select appropriate cloud-based collaboration tools. |

| Leadership | Directive leadership style. | Reiterate common purpose and expected outcomes. Conduct one-on-one site meetings with each team member. |

6.4 Communication Practices

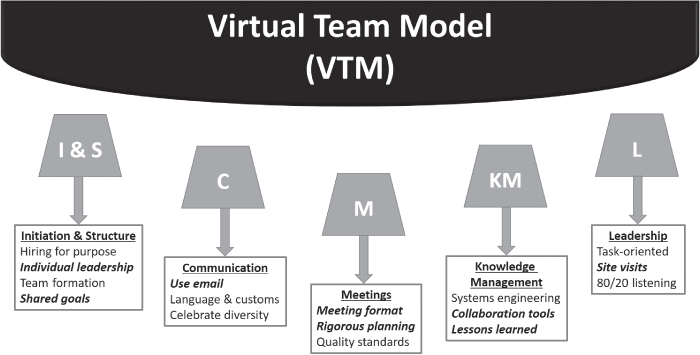

Not surprisingly, communication can make or break a virtual team because communication is critical for any relationship to succeed. The term “communication” includes both what we say and how we say it. More than 70% of communication is nonverbal (Aguanno, 2005) involving visual cues and body language. Obviously, virtual teams can lose a lot of the message when they use primarily asynchronous, technology-assisted means of communication. Yet, with the right approach to communication, virtual teams can be successful. We recommend a three-pronged approach addressing method (email), language, and cultural differences. (See Figure 6.2)

Figure 6.2: VTM practices for improved communication.

Email as a Primary Communication Tool

Virtual team members typically work in different time zones around the globe. One team member may be just logging onto the computer for the first time that day while another is shutting down to head home. Texting and instant messaging are common tools for communication today but can be disruptive for virtual teams. Nothing can be more frustrating than answering a “beep” on one's cell phone in the middle of the night and finding a simple, nonurgent message such as “Thx for sending the docs.”

Therefore, we agree with experts in recommending email as a primary communication tool for virtual teams. First, email is asynchronous and does not demand an instant response like a phone call or a text message. Second, email is inexpensive and can easily link group members together. Training is not required regardless of geographical location. Next, users normally are more careful in composing an email message, paying greater attention to grammar, spelling, and punctuation in order to clarify the message. An email can be composed, reviewed, and corrected before sending. Moreover, email can be organized in project folders to enhance knowledge sharing – a goal of lean NPD.

While it seems a good idea to include all team members on all communications, some issues will involve only a couple of team members. A best practice for virtual teams is to include names in the “To:” list that need to take action on the message while the “cc:” list is reserved for information only. “Reply to all” must be used with extreme caution. Moreover, it is crucial to include an appropriate subject line. Sometimes email chains grow and the conversation morphs from one topic to another. Because the team should not lose historical conversation threads, a best practice is to simply update the subject line. For example, if the original topic was the project schedule, but the conversation has changed, the subject line should now read “Subject: Construction Materials (re: Schedule).” This alerts receivers to the change in topic and preserves its relation to prior conversations. (Please see an example of email best practices in the box.)

Virtual Teams Use Language and Diversity to Build Creative Solutions

Team members must be proficient in the common language of the project. They must be able to both speak and write in that chosen language. As we've seen, written communications dominate in virtual teams, so writing skills will slightly outweigh verbal skills. Regardless of the team's selected language, it is important for colocated team members to use the common language in all communications. For instance, virtual team members will quickly become disengaged during a teleconference if team members at another location begin conversing in their native tongue.

Because email is the primary communication tool for a virtual team, team members need to be tolerant of odd sentence structure or peculiar phrasing. Nonnative English speakers, for instance, may translate their idea from a Romance language to English, resulting in longer sentences with a lot of descriptive clauses. Words may appear out of order (e.g. “coat blue” instead of “a blue coat”). All of us need to have patience with team members who may struggle to communicate in a different language. We also need to be receptive to clarifying meaning and intent if we are not as familiar with the written language.

Furthermore, emails and other communications should remain task-oriented. It is hard enough for friends and family to recognize humor in a text message. Trying to convey humor across cultures in an email message can result in misunderstandings and lead to unnecessary conflict. It is a best practice to keep communications succinct, focused on tasks, and action-oriented.

While emails may not be the right place to share humor or personal stories, a virtual team should celebrate their differences and build on the inherent positive aspects of their diversity. A fundamental benefit of a virtual team is the opportunity to tap into local market knowledge and practices and to use cultural differences to benefit the outcome of the project. Virtual team members of different educational, national, and cultural backgrounds bring different perspectives to a project; and they bring the viewpoint of multiple customers to ensure world-class design.

Cultural differences can sometimes be a challenge to virtual teams, just as language and humor are. Instead of trying to force the culture of the corporation's headquarters onto the virtual team, virtual teams establish their own culture and climate. Team members learn from the different cultures represented, and these differences will drive creativity for NPD. Product usage under various conditions found across the world will enhance the development of simple features that serve the needs of a wide customer base. Different mind-sets and backgrounds introduce more and varied solutions to problems. As team members share and build on one another's ideas, unique customer-oriented concepts evolve.

It is important for team members in a colocated, traditional team to adopt a single culture, and it is normally one that reflects the organization's broader culture. Virtual teams, in contrast, will celebrate their differences and adopt a unique culture and climate that builds on their own purpose in that time and space. A characteristic of successful teams establishes strong cohesion among team members. Open dialog and meetings in which knowledge is shared build trust and common understanding regardless of native culture.

Because team members in a virtual setting don't know what someone else knows (or doesn't know), it is critical for members to share their professional backgrounds and work experience. While discussion forums are usually underutilized to share work in progress or opinions, a discussion forum is a great place to share team member biographies. These biographies include information to build trust and enhance sharing.

For example, Marvin posts a photo of himself decked out in Cleveland Cavaliers basketball gear. He writes that he obtained his degree in mechanical engineering from The Ohio State University and has three kids. He also notes that he worked at two other companies prior to this job and has 10 years' experience in the telecom industry, of which one year was in management training.

Similarly, Wei Lu posts her biographical information as in Figure 6.3. Because Marvin and Wei Lu both love the same sport, they instantly build social trust. Moreover, Martin feels free to use sports analogies in meetings since he is assured that team members will understand a culturally narrow reference. What's different in this situation versus a noncommunicative virtual team is that the team members have intentionally shared professional and personal information to build trust and establish professional competency. Discussion forums and collaboration tools offer means of knowledge sharing and cooperative communication that build trust to support common project goals.

Figure 6.3: Example of dispersed NPD project forum.

Synchronous meetings for virtual teams start with a few minutes for members to share something about themselves to continue to build camaraderie. A good conversation starter will include questions about national holidays or sporting events. Another way to celebrate cultural differences is to ask one team member per meeting to share his/her biography in depth. Even without body language clues, other team members will be able to pick up a person's passions and energies.

6.5 Meetings and Protocols

Virtual teams are successful when there is a strong commitment to a shared goal and team communication focuses on achievement. Team members often work independently and will have fewer check-ins with other members than in traditional, colocated teams. Such team members may exchange ideas while at the coffeepot, water cooler, or company cafeteria. Casual interactions can stimulate deeper conversations leading to solutions of outstanding project issues or other problems. Thus, team meetings tend to be uneventful and serve more to inform the team leader of ongoing activities. Of course, virtual teams lack these opportunistic contacts with other members. Therefore, team meetings, protocols, and performance standards serve as critical checkpoints for virtual teams.

Select an Appropriate Meeting Format for Virtual Teams

Naturally, F2F team meetings involve informal information sharing, problem solving, and decision making. But most of these meetings also include the social aspect of building a shared identity. Alternatively, virtual team meetings serve to clarify roles and responsibilities, verify task performance, and validate project deliverables. Meeting format best practices for a virtual team include rotating meeting times and places, varying the technology medium, soliciting active participation, and rigorous planning. Clear follow-ups also are necessary.

Rotate Meeting Times and Places

Meetings for a virtual team are important touchpoints and connections for the dispersed members. Because team members spend a great deal of time working alone on tasks, team meetings provide an opportunity to establish group consensus, commitment, and shared understanding as well as decision making. Team goals should be reiterated at each and every team meeting to emphasize the common purpose and goals of the team. The time of meetings should be varied to ensure that it is convenient for all team members. It is unfair to ask the same team member to get up in the middle of the night every week for a team meeting. Instead, vary the time of day so that everyone on the team sacrifices equally.

Vary the Technology Medium

Likewise, try to vary the type of meeting. Teleconferences can be prone to multitasking (checking email or Facebook) during long conversations, and virtual team members may disengage from the conversation. Webinars with video force attention to the meeting topics at hand. Team protocols and norms describe how the virtual team members will interact at meetings. Simple actions, such as using the mute button and identifying oneself by name when speaking, can influence the team's positive communications to derive shared knowledge. Video conference and webinars encourage higher context communication but require more bandwidth. Remote team members and those in drastically different time zones often participate in meetings via cellphone. The use of a small screen dictates another set of standards for the team. In sum, while communication media may be designed for synchronous sharing, some virtual team members will necessarily participate in meetings with less bandwidth. Do not put them at a disadvantage. Appropriate planning and consideration for each meeting can smooth live interactions for virtual team members.

Solicit Active Participation from All Virtual Team Members

Because language and location are barriers to communication in a virtual team, meetings can face periods of stagnation. Participation increases not only when the times and media for virtual team meeting are varied but when task responsibility also rotates among team members. For example, facilitation of the meeting and distribution of meeting notes by different team members encourages more active participation by remote individuals and supports the team's common, shared purpose. Task sharing to present project milestones to the rest of the team encourages peer-to-peer communication and knowledge building.

Team norms also establish meeting participation protocols. For example, do all core team members need to be present at every meeting? Can a core team member send a stand-in to the meeting? Are meetings recorded and archived for those who miss one?

Finally, active participation in a virtual team meeting requires that team members speak up to share what they are working on, what challenges they face, and how their tasks lead to project completion. A quick check-in by the facilitator, calling out each team member by name, can lead to active participation by all.

Rigorous Planning Is Necessary for Engaged Virtual Team Communications

Important to planning a virtual team meeting is ensuring that an accurate agenda is distributed in advance. For virtual teams working in multiple time zones, distributing the agenda one week before a monthly meeting or two days before a weekly meeting is acceptable. Many agenda items comprise standing reports, obligations, and information sharing as well as problem solving and decision making that require interactive team member engagement. Agenda items will vary according to the progress of the product and are flexible enough to add new items when the meeting commences. Past follow-ups are noted on the agenda to mark completion or identify issues that impact accomplishing the product design.

Table 6.3: Managing an existing virtual product development team.

| Scenario: You are working on a project to add features and functionality to an existing product. The launch of the next-generation product is expected within a year. You estimate that about half of the work has been completed on the product's hardware and software elements. Unfortunately, two of the seven team members are new to the team, replacing one team member who was reassigned to another department and another person who left the company for a different job. | ||

| Virtual team model | Standard approach | Action for lean NPD |

| Initiation and Structure | New team members demonstrate comparable technical skills. | Use discussion boards and collaboration tools to share personal and professional biographies. |

| Communication Practices | New team members learn project status informally. | Welcome diversity and experience of new team members. |

| Meetings and Protocols | Informal welcome lunch for new team members. Casual conversations convey project status. |

Use video conference to introduce new team members. Rotate meeting management to new team members and invite them to share background and experience. |

| Knowledge Management | Transfer of tacit knowledge is informal. | Ensure adequate tool training is available for new team members. |

| Leadership | Builds social interactions and manages interpersonal conflict. | Leader visits one on one with each new team member. Paired site visits between new and existing team members. |

Distribution of the agenda in advance of a team meeting is crucial when team members are nonnative English speakers and cultures are very different. A detailed agenda allows the isolated team members time to plan their own responses and the opportunity to privately communicate concerns to the team leader or meeting facilitator as necessary.

Meetings of virtual teams tend to be more formal than those of colocated teams. Body language cues are missing from communications, and both language and culture can be barriers to successful virtual meetings. However, success of virtual teams is driven by a focus on the common, shared goal. The project objective should be repeated frequently throughout virtual team meetings to ensure task alignment. Meeting agenda items focus on task completion to deliver the new product efficiently. To help overcome language and cultural barriers, virtual team meetings start with a standing trust-building exercise to support the initiation and team formation social interactions.

Because Communication Practices and Meetings and Protocols are critical elements for long-term success of a virtual team, we emphasize and contrast the lean approach to build knowledge sharing with that of a standard approach in Table 6.3.

6.6 Knowledge Management

All teams depend on gathering, collecting, and evaluating information from a variety of stakeholders. Projects are initiated and planned by identifying key stakeholders and their requirements or expectations for the project. During project execution, these features and functionalities are tracked as part of the product development work. Projects should not reinvent the wheel every time a problem is encountered. In fact, lean project teams depend on learning and reusable knowledge for efficiency and productivity. Knowledge needs to be translated into explicit information to be useful to a virtual team. In addition to a successfully commercialized product or service, NPD teams should also contribute substantially to the knowledge base for future work.

Systems engineering offers many tactical and operational tools that will aid a product development team. These tools help the team ensure that technical linkages among subsystems are properly configured and designed for assembly. Version tracking and configuration management are key concepts in systems engineering. (For additional information, please see the references and contact the chapter's lead author.)

Collaboration Tools Eliminate Distance as a Barrier to Creativity

A wide variety of tools are available today to help virtual teams share information, transfer knowledge, and increase collaboration across distances. Groupware creates a common base for virtual team members and the virtual environment. New group collaboration tools are continually emerging as technologies continue to advance.

Document sharing tools, like Dropbox™, are a necessity for virtual teams to coordinate work and build shared databases and specifications for projects. Microsoft SharePoint™ is a common knowledge management tool for larger enterprises and traditional teams; however, the team should select appropriate collaboration tools based on its size and locations of team members. Other software tools assist indirect communication, like webinars and meetings. Whiteboard and desktop sharing allow virtual teams to collaborate across time and distance.

Robust project management tools are necessary for virtual innovation teams. These include traditional software tools like Microsoft Project™ to track schedule, budget, and resources. Many virtual teams opt for less expensive cloud-based project management tools such as Basecamp™, Wrike™, Asana™, productboard.com, Redmine, and the like. Software tools like Slack™, Yammer™, and I Done This (idonethis.com) engage team member communications as well as track project progress. Mindjet™, for example, provides a creative ideation tool that easily translates requirements into a Gantt chart so the team can focus on what matters most.

The advantage of cloud-based tools versus enterprise software tools lies in accessibility and maintenance of the tool(s) for the virtual team members. A team member with a home office does not have an information technology department on hand to troubleshoot software glitches. In addition to project management functionality, these cloud-based tools also provide a collaborative environment for the project team to work issues, store documents, and track email discussion threads while enhancing shared creativity, problem solving, and decision making.

The purpose of a lean innovation team is to develop a new product or service that is valued by customers around the world and to create reusable knowledge, not to learn new software. If a new tool is required by the team, it should be introduced with appropriate training at the kick-off meeting and not changed throughout the life of the project. The same technology should be used before, during, and after significant project milestones to increase productivity (Ketch and Kennedy, 2004). For instance, simply deleting the requirement for a passcode on conference calls improves accessibility for team members in remote locations or for those who are traveling outside of their home office. Communication and collaboration tools must be simple and easy for isolated team members to troubleshoot and access regardless of available technology capability. Tools and technology effectiveness are evaluated during a postproject audit. In addition to capturing specific product development information, the team should identify the most successful collaboration and knowledge management techniques.

Using Lessons Learned to Transfer Knowledge

Typically, lessons learned are collected after a project and are often discussed by a single team, then filed away with the project archives. In this common situation, lessons learned are rarely transferred between teams, and only a few outstanding items are captured by the project leader for future implementation. Traditional teams rely on word of mouth to transfer these practices and behaviors. Virtual teams, in contrast, rely on individual tacit knowledge and formal organizational practices for continuous learning.

An important goal, perhaps the number one goal, in applying lean principles to product development teams is to effectively and efficiently transfer knowledge. A company-wide shared database captures lessons learned and can be searched by anyone in the organization. Similarly, a Project Management Office or innovation department records and disseminates project learnings. The Project Management Office may sponsor a virtual project leader network encouraging free exchange of ideas and learnings during independent project activities. Reusable knowledge helps NPD teams deploy new products and services faster and with a higher degrees of success.

The use of virtual teams to accomplish these goals is mandatory in a globally competitive world. We illustrate the fourth element of the VTM, Knowledge Management, in the case study (see Appendix). Knowledge Management is key to successful lean NPD so that teams are not re-creating practices or relearning problem-solving techniques (see Tables 6.4 and 6.5).

Table 6.4: Using collaboration tools to generate reusable knowledge.

| Scenario: You are a technical project team member working on a new product for the company. Some of your teammates work from home-based offices, while others are scattered across the globe. You work out of a production facility so you have access to information technology and other company services, like human resources and payroll, but many of your teammates do not have these support functions available at their locations. During a recent team meeting via video conference, the team outlined the project expectations and working norms. | ||

| Virtual team model | Standard approach | Action for lean NPD |

| Initiation and Structure | Team members are specialists and participate as needed. | Actively participate in all team-building activities and the project kick-off meeting. |

| Communication Practices | Knowledge transfer is informal. | Use email instead of instant messaging for project communications. |

| Meetings and Protocols | Little documentation on task completion, status. | Complete assigned follow-ups on time. |

| Knowledge Management | Enterprise systems with strong information technology support. | Shared document storage and collaboration tools utilized. Share lessons learned, |

| Leadership | Manage status F2F. | Enable paired site visits to expand learning and customer viewpoint for product development. |

Table 6.5: Leadership for virtual team engagement.

| Scenario: You have been recently appointed the leader of a new product development team. The technical team is colocated at your site, but the marketing team is located across the country in another city while other designers and developers are located in India, China, and the Netherlands. You have led some very small project efforts in the past, and this is your first chance to lead a major product development team. | ||

| Virtual team model | Standard approach | Action for lean NPD |

| Initiation and Structure | Available resources on site. | Share project goals and expectations. |

| Communication Practices | Interactive F2F messaging. | Use email to introduce yourself as new team leader. |

| Meetings and Protocols | Informal decisions prior to meetings. | Practice rigorous meeting planning, including updates of issues log. |

| Knowledge Management | F2F knowledge transfer. | Study lessons learned on this project and similar completed products. |

| Leadership | Command-and-control focusing on social conflicts. | Visit each team member at local site office(s). |

6.7 Leadership

There is no shortage of research or literature describing what makes a great leader. However, most historical studies have focused on traditional teams, and leadership theory has evolved based on conventional, hierarchical reporting structures for management. Virtual teams are more egalitarian and leaders require a different skill set to demand success. Notably, traditional leadership has been only moderately correlated with virtual team effectiveness (Lurey and Raisinghani, 2001). Leaders for colocated teams, where conventional managers handle conflict and project status via informal mechanisms, have different roles from virtual team leaders.

Virtual team leaders, in contrast, are task-oriented, travel frequently to visit team members, and practice active listening. A directive or command-and-control style is rarely appropriate for a virtual team leader since team members are self-motivated, highly skilled technical experts. Moreover, leaders who emphasize social orientation and team cohesion above project goals are less likely to be successful on a virtual team that is more task-oriented.

Leadership training programs often fail to engage fundamental skills, like speaking, listening, and analyzing. Skills necessary for a virtual leader to be successful include flexibility, endurance, strength, self-control, and focus. Virtual teams require managers to adapt their style for each unique situation. According to Ivanaj and Bozon (2016), in a virtual setting, leaders can build trust by:

- Setting communication expectations quickly,

- Engendering a positive social environment,

- Validating rigorous meeting and team protocols, and

- Encouraging active participation for all team members.

Using Paired Site Visits for Knowledge Sharing

Because there are fewer routine and casual F2F interactions among team members, site visits are critically important for virtual teams. Certainly the leader should visit each team member at his or her local office regularly throughout the project life cycle. The leader acts as a liaison bridging communication needs for the team as a whole and reinforcing team goals.

By visiting team members locally, a virtual team leader can also better understand independent challenges facing them. Team leaders acquaint themselves with local management to improve negotiations (current and future) for materials, equipment, and workforce needs. Moreover, if the site lacks infrastructure necessary for the project, the team leader can take steps to rectify the situation. For example, one virtual team member needed to review hard copy documents for customers, but the local office only had a shared printer, which restricted her ability to access and review detailed project documents. After learning this during a site visit, the team leader acquired a personal printer for the team member, and her productivity greatly increased.

Site visits should not be restricted to the leader alone. Site visits include exchanges and are alternated among team member sites. A design team member visits the representative plant site and vice versa. The team leader facilitates these exchanges by assigning small, subprojects to pairs of team members. The benefits of site visits between team members are many. Misperceptions regarding workloads and task environments transform to reflect a common understanding among team members at the conclusion of site visits. Working side by side creates camaraderie and builds future trust for team members that extends beyond their return to their own home site. The project budget must account for these important exchanges since travel expenses are not always carefully considered as a part of the project budget for a colocated team.

6.8 Conclusion: What Makes Successful Lean Virtual Teams

NPD projects are inherently risky. Introducing a virtual team can further challenge the team's success. However, experience shows that implementing the lean VTM provides a framework to structure activities within a virtual team to achieve the dual goals of launching a new product and building transferrable, reusable knowledge.

Take action with your virtual NPD teams. Identify the largest gaps and initiate appropriate elements of the VTM. Better yet, institute the five elements and 16 practices of the VTM as the normal operating means for your teams. Check the structure of the team for shared purpose, ensure clear communication channels, and enforce team protocols. Recognize and celebrate diversity to drive creativity. Make it easy for each team member to contribute to the shared knowledge base to grow organizational learning. Encourage and facilitate paired site visits to enhance team effectiveness and achievement. Finally, recognize the benefits of a lean virtual team by speeding product development and tapping into a diversity of skills around the world.

Appendix: Case Study Application of the VTM

Adapted from Ivanaj and Bozon, 2016, pp. 238–250.

As a leading information provider in Financial and Risk, Legal, Tax and Accounting, IP Services, and Media, in 2009 Thomson Reuters implemented a new operating model to emphasize its global customer focus. The company reported over 60 000 employees in more than 100 countries with $12.5 billion in revenue in 2011. With the new operating model, Thomson Reuters recognized that virtual teams were the best way to accomplish the goal of a global focus. For example, in 2008, 50% of French employees reported to a manager abroad, and half of managers had teams spread over several countries and even different continents. About 400 people were involved in the organizational redesign to increase the global focus and improve virtual team capabilities. Success was recognized as the active transfer of knowledge, an outcome of running lean operations for virtual teams.

The Thomson Reuters global virtual team focus highlights all five elements of the VTM. First, with Initiation and Structure, team members were “hired” for purpose. The director of human resources at Thomson Reuters explained that a “prepared on purpose” organization is truly the only way an organization with a global customer focus – a virtual team – can succeed. Thus, virtual teams were built from those employees and staff members who demonstrated a capacity for change and management of the global client base. Team members were motivated by learning new skills beyond the restrictions of their geographic location. Individual leadership was emphasized by training generalists to become specialists as well as by providing additional training in personal organization and self-discipline. Next, team formation was utilized by structuring the teams for customer business segments: global, major accounts, trading, and investment. Finally, regardless of their geographic location, teams shared the goal of managing the client per specific business or product lines to drive the global customer focus.

Communication Practices is the second major element of the VTM. Thompson Reuters invested in mobile devices for all employees working on the global teams. This provided a way for all virtual team members to have access to email as a primary communication tool as well as other virtual collaboration technologies. Because the financial markets commonly use English for correspondence, individuals and managers at Thomson Reuters adopted English as the language for virtual teams. The transition was easiest in Anglo-Saxon cultures (such as United States, Canada, United Kingdom, and Nordic countries). Latin cultures (France and Italy) were less comfortable with the transition but supported English as the choice of language since account managers were often in a different country from the virtual team members.

The new globally focused client teams also celebrated diversity to improve trust among team members. For example, employees went to special training sessions to improve capabilities in flexibility, communication, and interpersonal competency. The group built a popular “culture wizard” website to assist staff in growing their culture and virtual intelligence. Virtual team members reported having more fun and higher individual satisfaction as a result of the new operating model accompanied by these new communication tools.

Meetings and Protocols were supported by rigorous planning. For example, some managers initially struggled with the discipline of holding regular online meetings, building effective agendas, and driving task completion. In response, Thomson Reuters offered logistical training to virtual team leaders on how to interact across time zones and how to run effective online meetings. The virtual teams also upheld a clear-eyed focus on the quality standards for their work. Maintaining and improving global client relationships was the prime objective for each virtual team.

As indicated in the VTM, effective Knowledge Management removes barriers to lean virtual teams, allowing them to produce results consistent with those of traditional, colocated teams. Thomson Reuters followed the practice of systems engineering by creating a central database and a customer relationship management system to traverse all their existing and new business processes. Further, the company invested in collaboration tools, such as a delivery network with document readers, video conferencing, and virtual presence. This allowed virtual team members access to the same information regardless of their geographical location. Lessons learned reviews unfortunately impacted some of the benefits realized by the virtual teams serving global customers. Some travel costs increased as managers occasionally traveled farther distances and influential clients requested specific personnel for in-person visits. However, team leader visits to various sites helped to improve communication as the manager serves as conduit to build trust and relationships among the virtual team members.

Finally, success in virtual teams and for a large-scale operational reorganization such as the one Thomson Reuters undertook requires strong, capable Leadership that is equipped for the challenges of a virtual team. As indicated, team leaders utilized site visits to introduce themselves to all team members and build the necessary interpersonal and social relationships. These actions served as an incentive for team members to build cross-functional trust and fostered team spirit. The company also committed to 80/20 listening as virtual managers were provided training that included cultural dimensions, “what if” scenarios, and a coaching mind-set.

While the VTM is designed specifically to help NPD teams succeed with their formidable challenges in creating new solutions for customer problems, looking at the Thomson Reuters case study validates the model's effectiveness in routine business operations as well. Virtual teams can benefit from a focus on Initiation and Structure of the team, effective and appropriate Communication Practices, Meetings and Protocols, Knowledge Management, and Leadership.

References

- Aguanno, K. (2005). Chapter 1: Introduction. In: Managing Agile Projects (ed. K. Aguanno). Lakefield, ON: Multi-Media Publications.

- Connaughton, S. L. and Shuffler, M. (2007). Multinational and multicultural distributed teams. Small Group Research 38 (3): 387–412.

- Hoegl, M. and Proserpio, L. (2004). Team member proximity and teamwork in innovative projects. Research Policy 33: 1153–1165.

- Ivanaj, S. and Bozon, C. (2016). Managing virtual teams. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Jurgens-Kowal, T. 2016. Bridging communication gaps in virtual teams. In Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Management 2016 International Annual Conference, ed. S. Long, E. -H. Ng, C. Downing, and B. Nepal. Red Hook, NY: Curran Associates, pp. 517–525.

- Ketch, K. and Kennedy, J. 2004. Unleashing the power of the group mind with dispersed teams. White Paper, GroupMindExpress.com.

- Lurey, J. S. and Raisinghani, M. S. (2001). An empirical study of best practices in virtual teams. Information Management 38: 523–544.

- Monalisa, M., Daim, T., Mirani, F. et al. (2008). Managing global design teams. Research Technology Management 51 (4): 48–59.

- Siebdrat, F., Hoegl, M., and Ernst, H. (2009). How to manage virtual teams. MIT Sloan Management Review 50 (4): 63–68.

- Ward, A. C. and Sobek, D. K. II (2014). Lean product and process development, 2e. Cambridge, MA: Lean Enterprises Institute.

- Zofi, Y. (2012). A manager's guide to virtual teams. New York: AMACOM.

Further Reading

- Loehr, J. and Schwartz, T. (2001). The making of a corporate athlete. Harvard Business Review 79 (1): 120–128.

- Project Management Institute (2013). A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide), 5e. Newton, PA: Project Management Institute.

- Shah, H. (ed.) (2012). A guide to the Engineering Management Body of Knowledge. Rolla, MO: American Society for Engineering Management.

- Smith, P. G. and Blanck, E. L. (2002). From experience: Leading dispersed teams. Journal of Product Innovation Management 19: 294–304.

- Tuckman, B. W. (2001). Developmental sequence in small groups (reprint). Group Facilitation: A Research and Applications Journal 3: 66–81.

About the Authors

DONOVAN RAY HARDENBROOK, NPDP, PMP, MBA, MSEE, is the Director of Global Quality Management Systems at Littelfuse Incorporated in Chicago, IL. He is responsible for advocating and driving a “Zero Defects. Zero Excuses.” quality culture and system across Littelfuse in the areas of product development and manufacturing operations. Mr. Hardenbrook is also responsible for standardizing quality systems and implementing product life cycle management. Prior to joining Littelfuse, Mr. Hardenbrook founded Leap Innovation Consulting in 2007 and has held previous management and engineering positions at Intel Corporation, Health Production Declaration Collaborative, Salt River Project, and Orbital Sciences. He is a 20-year member of the Product Development and Management Association (PDMA) and has served as the Book Review Editor for the Journal of Product Innovation and Management, Vice President of Association Development for PDMA, and founding President for the Arizona PDMA Chapter.

DR. TERESA JURGENS-KOWAL, PhD, PMP, NPDP, is the president of Global NP Solutions, LLC (GNPS), a boutique innovation training and consulting firm in Houston, Texas. GNPS helps companies achieve their strategic goals through new product development, product portfolio management, and project management best practices. Dr. Jurgens-Kowal has a passion for innovation and is a lifelong learner. She loves to help individuals and companies reach the highest levels of success in new product development and product portfolio management by gaining and maintaining their professional credentials, such as New Product Development Professional (NPDP), Project Management Professional (PMP), Scrum, and Lean Six Sigma. Dr. Jurgens-Kowal has a PhD in Chemical Engineering from the University of Washington, a BS in Chemical Engineering from the University of Idaho, and an MBA from West Texas A&M University. She has helped dozens of companies and individuals in diverse industries accomplish new product development goals of productivity and efficiency. Additionally, she has over 20 years of industrial experience and over five yeas' experience as adjunct faculty. She serves as PDMA's Book Review Editor and is a Registered Education Provider with PDMA.