8

DEVELOPING SOLUTIONS FOR UNDERRESOURCED MARKETS

Aruna Shekar

Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand

Andrew Drain

Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand

Introduction

This chapter provides guidelines on designing solutions for opportunities in underresourced markets. “Underresourced markets” are defined as communities in developing countries made up of resilient people who are not adequately served by currently available products, services, or infrastructure. While the literature uses many terms to describe this user group, such as base of the pyramid, emerging or developing market, or resource-constrained market, for clarity, the authors utilize a single term for clarity: underresourced market.

Underresourced markets offer many opportunities for innovators, but product developers must learn about the specific requirements of the users and market segments first. Traditional approaches are not suited to these resource-constrained environments, as they are based on Western ideology and assume the product developer has an implicit knowledge of the market and user group. This chapter begins by introducing the inadequacies of the traditional new product development (NPD) process for addressing underresourced market constraints. These constraints are then presented, discussed, and illustrated through project examples. Adaptations to the standard process are suggested as a way of leveraging these market constraints to improve product adoption. The chapter ends with some keys to success and pitfalls to avoid when looking to create products for under-resourced remote markets.

8.1 The Traditional New Product Development Process

Cooper's (2014) Stage-Gate® process provides structure to the development and commercialization of new products for developed markets. This model shows the clear focus expected at each stage in the process and provides process “gates” where particular deliverables are required. It also suggests user interaction at each stage in the process to assist in validating ideas as they transition toward physical products.

While many other design processes could be mentioned here, the underlying sentiment of all of them is similar: a large number of ideas, user interaction, and the ability to iterate early. However, while the utility of these principles is not disputed here, there is an obvious difference in success between projects in developed (resourced) versus underresourced markets (Chandra and Neelankavil, 2008). This is due to user and market constraints limiting a product developer's ability to meaningfully interact with underresourced market end users and understand the complexities of the sociocultural environments in which they live.

The reliance on traditional NPD processes, based on technology and internal capabilities, has resulted in the introduction of new products to global markets that have had limited penetration in developing countries, especially for the underresourced market demographic. While the single biggest constraint in developing products for underresourced contexts is affordability, affordability alone, at the expense of functionality and aspirational value, will not be successful. Many failures in underresourced markets are due to a lack of in-depth understanding of user needs and problems. This understanding has led to a greater focus on user-centered or codesign approaches to identify the factors related to key constraints. What are some of the key factors that need to be considered in NPD for underresourced markets?

8.2 Factors to Consider when Designing for Underresourced Markets

The examples given later highlight a number of factors that need to be considered very early in the design process. These factors are centered on identifying user and market constraints that will impact product requirements (see Table 8.1).

Table 8.1: Key factors to research in the specific underresourced market.

|

User (earns less than $2 a day) |

Market context | Product |

|

|

|

The three columns in Table 8.1 refer to particular factors relevant to users, market contexts, and products that need to be researched and considered before developing solutions. While studies have highlighted that most rural individuals have low incomes, low formal education levels, and generally engage in agricultural practices, it is important to not rely on these assumptions alone. As explained in the rice cooker example later in the chapter, ethnographic techniques and role-play are effective ways to learn about end user requirements that a product must address, specific to the market in which it is to be used. Product developers should observe and learn how rural consumers go about their daily lives within their specific environment. They must talk to users and listen carefully to understand their goals, values, and attitudes and at the same time be open to user suggestions. Mutual learning and collaborations between the product developers and user communities must take place early in the NPD process.

Failures of medical products and of personal hygiene and home appliances that were targeted at rural markets in developing countries have shown that success is not as simple as transporting a product created in the West to a rural context (Shekar and Drain, 2016). NPD practitioners have found that establishing contacts with end users in remote rural villages in developing markets is challenging due to differences in languages spoken, the remoteness of some communities, and the lack of communication infrastructure.

The differences in market context conditions are so significant that they must explicitly be taken into consideration at the front end of NPD. Many new product entrants focus mainly on cost reduction of an existing product in order to enter these underresourced markets, which ignores much of the social and cultural value inherent in a new product. New approaches are required for a better understanding of unfamiliar markets, users, constraints, sociocultural issues, and infrastructures.

A useful framework for considering design for underresourced markets are the eight product indicators associated with success: affinity, desirability, reparability, durability, functionality, affordability, usability, and sustainability (Whitehead et al., 2014). These eight factors must be considered early in the product design process and verified through fieldwork. These indicators can help translate user and market constraints and requirements to product characteristics.

Rural areas in developing countries can have a number of constraints, such as lack of electricity, lack of road and transportation infrastructure, limited access to potable water, poor sanitation facilities and waste management, inefficient cooking methods, and labor-intensive methods of food preparation and transportation. However, no two areas are the same, meaning static assumptions about community deficiencies can be just as dangerous as no consideration at all. It is therefore clear that a new approach is needed to understanding the complex user and contextual constraints present in underresourced markets.

Understanding people's lifestyles and their living conditions in specific rural communities has been shown to be critical, but how can companies or practitioners source in-depth information for NPD from a distance? Should they collaborate and, if so, with whom and how? How can they learn about the stakeholders and the needs of communities? How can they carry out a field test for a product? These questions are addressed in next sections.

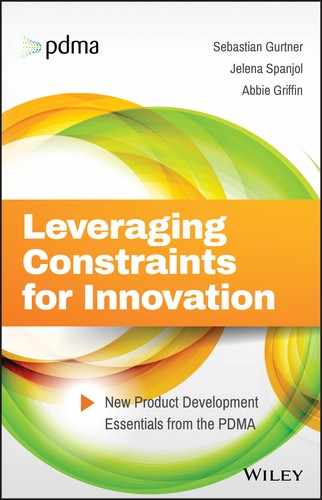

8.3 A New Approach for Underresourced Markets: Obtain User Knowledge and Partner with Local Organizations

Some companies have successfully developed products for markets in developing countries resulting in long-term profits. They have done so by shifting the focus from internal firm capabilities to utilizing organizational networks in underresourced markets and working closely with rural end users to truly understand the needs the product must address. A typical user approach that is undertaken in developed markets, where a company interacts directly with its users, is shown as a simple schematic diagram in Figure 8.1a. However, in an underresourced rural context (Figure 8.1b), this approach is not advisable due to the constraints listed in Table 8.1. Figure 8.1c highlights the new approach that is suggested when preparing to enter an underresourced market. Companies should work through an international nongovernment organization (NGO) such as Engineers Without Borders and partner with a local NGO and other key stakeholders to gain access to information and build trust within the community. Typically, rural villages have “chiefs” or village elders who are highly respected by the community. Getting their support can help with dissemination and adoption of social innovations within the community. Companies and product innovators can benefit by working closely in equal partnerships with user communities for mutual gains. Both parties can bring their perspectives and knowledge to the problem-solving and design discussions. Examples of these are given in the next two subsections. An examination of several unsuccessful and successful NPD projects aimed at underresourced markets have resulted in the following lessons learned.

Figure 8.1: (a) Typical approach in a developed market. (b) Common challenges in underresourced markets. (c) New approach for underresourced markets.

Lessons from Unsuccessful Projects

Many product failures have resulted from designing solutions that were dependent on utilities that are taken for granted in Western markets, such as continuous electricity or potable water. Others have failed because designers did not communicate with the community or consider the cultural differences and implications of their solution.

For example, Bosch and Siemens Home Appliance Group's Protos plant oil stove initially failed because the product was rigidly designed for cooking in the home and involved the introduction of new technologies and the use of plant oil for fuel, which did not take into account the lack of a local stove service network or supply of the required plant oil. These contextual constraints were not identified until the field-testing stage, resulting in a waste of time and money.

In another example, providing infant formula to rural households in Bangladesh did not succeed because mothers did not know how to use it and could not differentiate between infant formula and milk powder. Huge amounts of foreign investments are wasted yearly due to failures to account for local customs, cultures, and behaviors by not consulting with individuals in the community about their specific context.

A project on shaving razors for men in rural India failed at first because the developers did not consider user access to running water, which was required during the product use stage. To avoid making a trip overseas, developers tested the product with international Indian students in the United States; however, these students had access to electricity and running water. Visits made to rural homes in India after initial failure discovered that men shave differently and their requirements were different too. For these users, safety in terms of not getting cut was more important than a close shave (as often they would shave in the early hours of the morning when it was still dark in their homes). After the razor was redesigned specifically for these emerging markets, it gained market share as it was relevant to the specific user needs and contextual constraints.

From these examples, it can be seen that it is important for product innovators to visit the specific market and interact closely with community members before and during product development.

Lessons from Successful Projects

An example of a successful product release is the approach Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL) took to selling shampoo in 500,000 villages across remote parts of India. While entering this new market presented challenges, such as a lack of distribution infrastructure and a lack of disposable income among end users, the use of research information and market-specific product innovations ensured that the new product was a success. First, HUL developed a single-use shampoo sachet to address affordability within the target market. Second, sales training was provided to local women who then acted as product distributors.

Another example is the Tunsai, an innovative water filtration device distributed by iDE Global in Cambodia to rural communities in Southeast Asia. It utilizes locally manufacturable clay pots to filter contaminants from water as well as a simple design to ensure a low retail price. The product was successful, and it then allowed the company to identify an opportunity to provide a higher-quality product that contained more ergonomic and aesthetic considerations. The Super Tunsai was released to appeal to the emerging segment of users to provide a level of aspirational value to an otherwise inexpensive product.

The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NUST) developed effective partnerships with multiple local organizations to design a new type of prosthetic aimed at being more appropriate for children and more effective in the wet and muddy farmlands in Cambodia. The local organizations included the International Committee of Red Cross, Regional Physical Rehabilitation Centre, Phnom Penh Orthopaedic Component factory; and local Khmer villagers and children (Hussain et al. 2012). This collaboration helped NUST understand the product, user, and contextual constraints fully, resulting in prosthetics with molded toes and a wider base for walking through mud.

These successful examples show the importance of understanding users' abilities to purchase a product, from both a cost and a distribution perspective, as well as their aspirations and the social value of owning a product. The only way to learn about such complex requirements is through direct interactions with end users and meaningful fieldwork in collaboration with local organizations.

Next we describe in more detail a successful project example and explain how fieldwork was planned and implemented in a Cambodian village. The text highlights once again the importance of interacting with users in their environment and partnering with local organizations. It shows the importance of stakeholder engagement, hands-on field research, and product trials within the actual product environment.

The Cambodian Rice Cooker: An Example of Meaningful Fieldwork in Collaboration with Local Organizations

This project involved researching failure modes to develop of design improvements for a low-cost rice cooker fueled by methane-rich biogas. The authors worked on the project for a social enterprise based in Cambodia (referred to as Company A) and in a collaborative relationship with the international NGO, Engineers Without Borders.

The field research investigated why current rice cookers were failing during usage within homes and how design changes could be made to reduce or eliminate the identified failures. While the collection of field data was instrumental to project success for a contextually appropriate solution, local manufacturing capabilities and user habits also were critical to improving the product.

Project Definition

The project was initiated by a Cambodian social organization based on feedback from rural development organizations and users that rice cookers were failing after an unacceptably short period of time. The rice cooker products initially were bought from an external supplier and distributed as an auxiliary product to Company A's main offering, a large organic material digester that produced biogas as a replacement for cooking over wood fires. Because of the cookers were bought externally, little was known about their detailed design or how they would operate in the rural Cambodian context. The main reasons for introducing biogas rice cookers were the heavy reliance on rice in the Cambodian diet and the opportunity to introduce a clean energy source for the cooking of rice. The project included four stages:

- Background research

- Contextual research

- Failure mode analysis

- Product redesign

This case study focuses on the importance of Stage 2 and the use of micro-ethnographic techniques to learn about how people interact with the product during usage and maintenance. The aim of this project was to “redesign an off-the-shelf biogas rice cooker to eliminate the current failures while being locally manufacturable, maintainable, and affordable.” It was also within the scope of this project to define exactly what local manufacture and maintenance skills were available.

When this project was initiated, very little was known about how the rice cooker was used in context or why exactly the product was failing. Much of the feedback Company A had received was through word of mouth from their contacts in rural development organizations, with no empirical data or physical products to examine. What was believed was:

- Rice cookers were no longer functioning correctly after an unacceptably short period of time. This may have been due to corrosion or blockages in the gas flow.

- Rural users were not maintaining important components of the biogas system due to lack of knowledge and lack of access to spare parts.

- Hydrogen sulfide (a corrosive compound that is a by-product of the digestion process in the biodigester) was a contributing factor to failure, potentially due to a lack of required filtration.

While all of this information seemed plausible, it had been discovered through secondary sources and did not take into account user-centered design methods. Logistical constraints, such as access to the remote areas in which the product was used and limited staff resources, were the main reasons for this initial reliance on secondary sources.

Alignment with a Traditional Stage-Gate Development Process

The initial implementation of the rice cooker by Company A followed a traditional Stage-Gate process. The idea of introducing a rice cooker product was supported by a business case built around the relatively cheap cost of importing off-the-shelf units. While extensive technical development was completed on the biogas generator product, little attention was paid to the rice cooker as the complementary product supporting the biogas generator value proposition. It was assumed that adequate development had been completed by the manufacturer and that Cambodian market constraints would not require additional consideration.

Adaptation of a Traditional Stage-Gate Process

To ensure project success, a strong focus needed to be shifted from internal technology testing to user-focused usability and maintainability. This shift required obtaining access to multiple end users in rural areas of Cambodia as well as open discussions with them about the product. To facilitate this, a rural development organization was contacted and a partnership was formed between Company A and the rural organization.

Background Research

Before traveling to Cambodia, a number of areas needed to be researched in detail by the product developer to ensure that the fieldwork would be effective. First, a basic understanding of Cambodian culture, including community dynamics, language, and demographic information, was required. This was critical to interacting appropriately and effectively with end users, but also in interpreting findings and analyzing user behavior. To ensure this step was undertaken effectively, a number of training workshops were attended with NGOs and training providers in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Second, technical research was undertaken on corrosion processes in biogas applications, chemicals, and materials as well as uncovering existing solutions to these problems in other applications.

Field Research: Fly-on-the-Wall Ethnography and Role-Playing

A development organization in the South Cambodian region of Takeo was used to schedule visits with rural families who had been provided with the biogas rice cookers. While a basic plan was developed, it was important to be flexible due to community priorities and environmental situations, such as monsoon rains. The plan involved accompanying two local technicians as they visited a number of biogas users in the community to discover failed or failing products. To assist with the natural discovery of local insights, two techniques were used: micro-ethnographic fly-on-the-wall research and role-playing.

Fly-on-the-wall ethnography is difficult because employees of the biogas firm are obvious outsiders and a translator must translate for them. It is therefore important to view the engineer's role in this activity as an observer who can be seen by all participants in the activity. Local facilitators should engage with participants and allow for natural interactions to occur between themselves and end users.

To encourage active participation from community end users and local technicians, a broken unit was used as a visual artifact for investigations and further discussions. The aim was to enable both end users and technicians to participate in active discussions about three areas:

- Why did users believe the product was failing?

- What, if anything, had they done to fix/minimize this failure mode?

- How would they propose the product be changed?

The fly-on-the-wall activity involves three steps:

- Align with a locally known individual who will elicit interaction with others in the community. In this case study, a local technician was chosen, as such technicians regularly interacted with families in the community.

- Focus interactions around a clear question about the product. In this case study we focused on the failure modes (parts likely to fail) of the rice cooker.

- Firm employees attend as silent observers but are prepared to engage with the group. It is important that the developer does not act as an “invisible” observer, as this may create a sense of unease in the group. The developer should attempt to withdraw from interactions but be ready to engage in a friendly manner.

While this ethnographic activity is helpful for documenting product change ideas from the technicians, it was harder to get information about product usage conditions that led to failure. To aid in this enquiry, the participatory design technique of role-play was employed.

The purpose of role-playing was to utilize live, acted-out scenes to learn about product aspects that did not naturally arise during conversation or the fly-on-the-wall method. To enable this to occur, a number of investigative questions were used to build a small amount of momentum in the session. Users were then asked to guide a tour of their kitchen and biodigester. This activity allowed the team to learn about the exact system the family had in place and also whether environmental factors, such as rain, dust, pests, or animals, were having a potential impact on the product.

The first role-play demonstrated users' cooking habits including meal preparation, cooking, and cleaning. The role-play activity implemented three steps:

- Explain a scenario to the participants. In this case study the two scenarios explained were the use of the product for cooking rice and the diagnosis of faults if the rice cooker stopped working.

- Allow time for the activity to gain momentum. Be prepared for this activity to start slowly as participants process the instructions and draw from their memory to form a scene. Facilitators may need to prompt participants at the beginning but should look to exit as soon as possible to avoid biasing the natural flow of the scene.

- Keep the scope of this activity wide and allow for the scene to transition into new areas. It is important that facilitators do not enforce strict boundaries for this activity. Restricting scenes to a small scope may result in separate, but important, factors being missed. Facilitators should begin the activity with a small, clearly defined scenario but then allow for the activity to expand naturally.

Having learned that the technicians serviced a number of rice cookers a month, in a second role-play task, they were asked to role-play how they diagnose a fault and then list common issues and solutions. This role-play again took time to build momentum, with one of the facilitators starting the scene by dismantling a rice cooker. Once the technicians felt comfortable with what was expected, they spent two hours explaining in detail many issues faced and how they would usually rectify these issues. A number of scenarios were then proposed to the technicians as a way of investigating as wide a scope as possible. From this activity, corrosion of critical components was identified as a failure mode as well as seals breaking due to lubricants being removed during the maintenance process. A number of initial design ideas were also gathered from both the end users and technicians.

Failure Mode Analysis

The community visits resulted in two important outputs: Valuable information regarding product user interactions and maintenance issues was obtained, and physical broken rice cooker parts (shown in Figure 8.2) that could be analyzed to triangulate some of the information were gathered. The technical analysis is outside the scope of this chapter; however, spectral analysis and electron imaging were used to identify the types of corrosion present on the units and to analyze the gas flow from the biodigesters to identify potentially harmful components.

Figure 8.2: Biogas rice cooker: corroded parts.

Product Redesign

From both field research and technical analysis, a number of potential product changes were identified, including material and geometry changes of critical components, service training, and spare parts, as well as the potential for creating sealed units in the cooker to avoid the possibility of lubrication being removed accidentally.

The project helped to discover this important information:

- The originally suspected failure modes (from secondary sources) were not accurate but did provide guidance for end user visits.

- Product user interactions were different from what the organization originally anticipated.

- The initial role of the local technician was underestimated and needed to be given more focus during both product design and servicing.

The field study identified the specific failure modes of the product and used these to suggest design improvements, based around the main constraints of being affordable and locally manufacturable. The redesigns reduced corrosion and prolong the life of the rice cookers.

8.4 Lessons from the Field Study

This section presents several lessons learned from undertaking the field study.

Partner with Intermediaries

Due to language and cultural differences, it is best to work with a local partner social enterprise, NGO, or university. These organizations are familiar with the behavior, needs, and practices of rural villagers. They generally have local networks and language translators they already have worked through and with.

Community chiefs or village heads are also key stakeholders to be consulted with early on in the process. It is beneficial to build a relationship with these leaders, as the community respects them. Their support can help with a roll-out of products into a new market. Local partners have also often built a relationship with these important community leaders.

Understand the Market and Users

Designers must be prepared to solve problems collaboratively with users, communities, and local organizations right from the very start. Involving key users throughout the process enables people to air their frustrations and voice their suggestions. End users often have a good knowledge of contextual factors, traditional practices, and insights into current local constraints and solutions.

In terms of market and environment constraints, the infrastructure, such as roads, power, water, and wireless communication, must be taken into consideration when looking to develop a product that may depend on such infrastructure. While many underresourced markets will be lacking in certain areas, there may well be opportunities related to infrastructure development. For example, Myanmar has transitioned from almost no telecommunication infrastructure to widespread 3G coverage and affordable internet-enabled smartphones in just a few years, partly due to large amounts of international investment. To assume that rural underserved communities in Myanmar have no mobile phone or internet access removes a potentially effective product launch communication tool.

It also is important to understand the sociocultural environment in which product testing occurs. For example, in some Asian cultures “saving face” is a strong custom that inhibits individuals from expressing critical opinion. This was witnessed firsthand while interacting with women in a small village during the rice cooker field study in Cambodia. Many commercial projects have failed because they do not take into account local behaviors and attitudes. In most cases the research appears to be carried out after the failure to determine why the product failed rather than research being done up front. Other causes for product failure include dependency on factors such as clean water supply, continuous access to electricity, expensive spare parts for maintenance, and other assumptions about infrastructure in underresourced markets.

In terms of product constraints, consideration must be given to the ease of construction, maintainability, robustness, effectiveness in addressing local needs, affordability, and simplicity. It is worth noting that in many underresourced cultures, people generally reuse or repair things, as they cannot afford to keep replacing items. Hence, products should be kept simple and modular so that only specific parts must be replaced. Expecting people to dispose of a single-use product is an assumption that needs to be verified through fieldwork. If in the users' eyes the product still functions, they are likely to reuse it for a longer period of time. Hence it is imperative to design products that are durable, rugged, and can be reused or have inexpensive parts that can be replaced easily by end users. Smaller portions or sachets have been successful for rural consumers as they allow them access to a product previously too expensive to purchase in bulk.

8.5 Adaptation of NPD Processes for Underresourced Markets

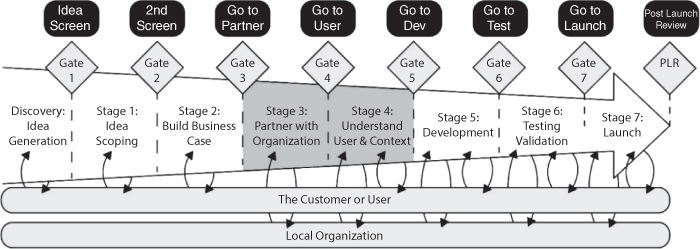

Based on the field study and examples, the authors propose the addition of two early stages (shown in Figure 8.3) to the standard NPD process:

Figure 8.3: Adaptation of NPD process showing links with local organization.

- Partnering with local organizations

- Understanding the user and market

The addition of stages that explicitly guide the product developer toward partnership, empathy, and external knowledge is important as it ensures market knowledge is gained before the traditional testing stage. The “Partner with organization” stage involves research into the NGOs, social enterprises, and universities that best represent the target market (geographically, demographically, and in terms of values and goals). It also requires contacting and building relationships with those key organizations, which will take time. The benefits of this partnership will become apparent as development and testing in the actual environment becomes simpler and even more valuable.

The stage of “understand the user and market” already may have occurred informally during project scoping and idea generation. However, it is during the development and detailed design stage that in-depth knowledge of the market (as noted in Table 8.1) becomes critical to product success. It is at this stage that field trips into representative communities should be undertaken by product developers, in conjunction with local partners. As shown in the rice cooker field study, it was only through firsthand interaction with end users that the underlying issues could be uncovered. It is at this stage that Whitehead's eight product indicators – affinity, desirability, reparability, durability, functionality, affordability, usability, and sustainability – can be used to structure investigations.

NPD User Interactions in Underresourced Markets

Mutual learning and collaborations between the product development team and users are important, as local users have the best and most complete understanding of some of the contextual issues and problems. End users can offer some traditional solutions and methods based on their own knowledge that has been passed down from generation to generation. We have come across some clever indigenous solutions, such as adding crushed seeds to clarify water and using native plants to make containers and packages (to reduce or avoid the use of plastics). Empowering people with the confidence and abilities to solve some of their problems themselves may help produce sustainable solutions.

Keys to Success

- Market immersion. A focus on the front end of the NPD process to research and learn about the users, product requirements, and contextual constraints is critical. Observe and understand the market environment in a more holistic manner. (See Chapter 7.)

- Empathy. Having concern and care for the people, their lifestyles, needs, and wants, goes a long way in producing a better suited product. User-centered approaches facilitate this learning and ensure that the product meets user requirements.

- Field testing. For any product or service to succeed in a new environment, it must be tested in the actual location by target users before implementation takes place. This testing is critical even if accessing that remote location is a challenge. Earlier simulated tests may be conducted in labs or with people from the target market. However, be aware that these conditions may not be identical to the actual rural market environment.

- Collaborations for success. It is critical to involve key local partners, such as NGOs, community leaders and users, manufacturers, and universities. Clarify and define at the start what their capabilities and roles are.

Pitfalls to Avoid

- Do not assume that the product will work in a new location without doing up-front research. Mere functionality of a product is not enough; it must function properly within the actual market context and conditions.

- Do not assume that purchasing decisions of people in underresourced communities are driven only by initial cost.

- Do not assume all underresourced communities are the same. Market constraints will differ based on sociocultural, economic, and geographical influences.

These guidelines are aimed at practitioners or companies looking to develop socially oriented solutions and consumer products for underresourced contexts.

8.6 Conclusions

This chapter has outlined some of the successful practices in developing solutions for underresourced contexts. Traditional NPD processes struggle to guide international companies to successfully establish themselves in underresourced contexts, because they are built on Western practices and markets. The chapter draws on examples in the literature as well as on project experiences and presents the factors to consider when designing for a community with extreme constraints. Questions such as whether to collaborate with a community partner, how to conduct field research, and what modifications need to be made to the standard process to design appropriate solutions are answered here.

In order to create solutions that are better suited to local needs, certain factors must be researched and taken into consideration early in the NPD process. Table 8.1 provides a list of key factors and constraints to be considered when designing for underresourced contexts. The rice cooker example described a method of investigating and incorporating field testing in a rural setting as a way of identifying some of these factors that are specific to a community or market context.

Solutions that are meant for rural villages must be better suited to the context and needs of people living there. Early collaborations with key local partners help clarify needs and issues and provide insights into contextual requirements. Community partnerships are vital enablers in designing appropriate products for these markets.

In summary, traditional approaches to social product innovation are inadequate in underresourced environments. Examples of a range of commercial endeavors highlighted the requirement for in-depth early research to identify market and user factors before designing solutions for underresourced contexts. These markets present different user needs and sociocultural habits that must be considered early in the NPD process. The adapted development process, keys to success, and pitfalls to avoid provide guidelines to help address some of the current issues of product failures in underresourced contexts and result in more appropriately designed solutions.

References

- Chandra, M. and Neelankavil, J. (2008). Product development and innovation for developing countries: Potential and challenges. Journal of Management Development 27 (10): 1017–1025.

- Cooper, R. G. (2014). What's next? After Stage-Gate. Research-Technology Management 51 (1): 20–31. doi: 10.5437/08956308X5606963.

- Hussain, S., Sanders, E. B. -N., and Steinert, M. (2012). Participatory design with marginalized people in developing countries: Challenges and opportunities experienced in a field study in Cambodia. International Journal of Design 6 (2): 91–109.

- Shekar, A. and Drain, A. (2016). Community engineering: Raising awareness, skills and knowledge to contribute towards sustainable development. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education 44 (4): 272–283.

- Whitehead, T., Evans, M. and Bingham, G. (2014). A framework for design and assessment of products in developing countries. http://www.drs2014.org/media/654441/0313-file1.pdf.

About the Authors

DR. ARUNA SHEKAR is a Senior Lecturer and Major Leader in Product Development at Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand. She has taught at the university for more than two decades and has coordinated the final-year capstone projects with industry. She continues to champion the application of creativity and design skills to generating meaningful solutions that are strongly user focused and context appropriate. Dr. Shekar has led the first-year social innovation course in conjunction with Engineers Without Borders for four years, with her students winning national or Australasian awards every year. She has many publications to her credit in international peer-reviewed journals and refereed conference proceedings, including a chapter in the book Open Innovation: New Product Development Essentials from PDMA. She has presented keynote speeches and served as program chair at several conferences. Dr. Shekar is a Foundation Board member of the Product Development and Management Association in New Zealand. She was appointed Vice President for Global Affiliates of the Product Development and Management Association in the United States in 2016, and interacts with leaders and affiliates in the Asia-Pacific.

ANDREW DRAIN joined the Massey University School of Engineering and Advanced Technology at Massey University, New Zealand, in 2015 as a lecturer with a focus on product design and humanitarian engineering. His research focuses on the role of participatory design processes in the creation of technology with communities in developing countries. While his research includes a range of engineering applications such as sanitation, cooking, and domestic electronics, the design of assistive technologies with people with disability is the focus. This is due to the challenges individuals with disability face in rural areas of developing countries and their aspirations to be involved in local social, religious, and economic activities. He has worked as a product developer in the medical industry and more recently as a consultant in rural areas of Cambodia and India. He has published in creativity-focused journals such as CoDesign and has received a Red Dot Design Award for his humanitarian product development work.